Abstract

Objectives

High rates of antituberculosis treatment discontinuation have been reported in some areas of Africa. The aim of this study was to determine the rate, time to and determinants of antituberculosis treatment default in Yaounde.

Design

This was a retrospective cohort study based on hospital registers. Tuberculosis treatment default or antituberculosis treatment discontinuation was defined as any interruption of treatment for at least 2 months following treatment initiation. Sociodemographic and clinical predictors of treatment discontinuation were investigated with the use of Cox regressions models.

Setting

This study was carried out in the tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment centre at Yaounde Jamot Hospital, which serves as a referral centre for tuberculosis and respiratory diseases for the capital city of Cameroon (Yaounde) and surrounding areas.

Participants

All (1688) patients started on antituberculosis treatment at the centre between January and December 2009 were enrolled. Outcome measures were antituberculosis treatment default and time to treatment default.

Results

Of the 1688 included patients, 337 (20%) defaulted from treatment, 86 (5.1%) died, treatment failed in 6 (0.4%) and 104 (6.2%) were transferred. Therefore, treatment was successfully completed in 1154 (68.4%) patients. Median duration to treatment discontinuation was 90 days (IQR 30–150), and 62% of treatment discontinuation occurred during the continuation phase. Hospitalisation during the intensive phase (adjusted HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.54 to 0.89) and non-consenting for HIV screening (1.65; 1.24 to 2.21) were the main determinants of defaulting from treatment in multivariable analysis.

Conclusions

The default incidence rate is relatively high in this centre and treatment discontinuation occurs frequently during the continuation phase of treatment. Action is needed to improve adherence to treatment when received on an ambulatory basis, to clarify the association between HIV testing and antituberculosis treatment default, and to identify other potential determinants of treatment discontinuation in this setting.

Article summary

Article focus

To determine the rates, time to and determinants of antituberculosis treatment discontinuation in the era of directly observed treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, using the situation in Cameroon as an example.

Key messages

Antituberculosis treatment success rates remain sub-optimal in sub-Saharan Africa, a region which has the highest global incidence rates of tuberculosis.

Treatment discontinuation is one of the main reasons for the high tuberculosis rates, but has not recently been fully explored in Africa.

Knowledge of the determinants of antituberculosis treatment discontinuation is critical for informing health service and policy solutions needed to improve the outcomes of care for tuberculosis and contain the spread of the disease.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This was a large cohort study with 1688 participants.

This was also a retrospective study which lacked some key information.

Introduction

Tuberculosis is endemic in the majority of sub-Saharan African countries where the highest global annual incidence rates are recorded.1 The expected therapeutic success target of 85% among newly diagnosed individuals with positive smears is largely unachieved in many settings in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Defaulting from tuberculosis treatment is one of the reasons for this sub-optimal performance. Tuberculosis treatment default or antituberculosis treatment discontinuation is defined as any interruption of antituberculosis treatment for at least 2 months following treatment initiation.2 3 Antituberculosis treatment discontinuation is associated with disease reoccurrence following treatment, increased mortality, maintenance of micro-organism reservoirs and emergence of drug-resistant species of mycobacterium.4

The directly observed treatment (DOT) strategy has been recommended by the WHO5 for improving the outcome of care for tuberculosis. Implementation of the DOT strategy started in Cameroon in the mid-1990s and was expanded to the entire country in the year 2000. Despite this, available evidence suggests that antituberculosis treatment discontinuation has remained relatively high.6 Many factors have been linked to antituberculosis treatment discontinuation in sub-Saharan Africa, including infrequent bacilloscopic monitoring, transfer of patients across health service units, lack of family support, side effects of medications, healthcare system factors and patient misinformation.7–9 In general, studies on the determinants of antituberculosis treatment discontinuation in Africa and in Cameroon are generally outdated and less reflective of the DOT and highly active anti-retroviral therapy eras, and the few relevant studies are heterogeneous.7 8 In addition, none of the relevant studies were conducted in Cameroon after DOT was implemented. In this context, therefore, updated information is needed on antituberculosis treatment discontinuation and determinants that reflects both the DOT era and recent improvements in access to HIV testing and treatment, in order to guide further improvement in the outcomes of care for tuberculosis.

The aim of the current study was to assess the incidence rate, determinants and time to antituberculosis treatment discontinuation in the real-life setting of a tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment centre in Yaounde, Cameroon.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in the pneumology department of Yaounde Jamot Hospital, which serves as a referral centre for tuberculosis and respiratory diseases for the capital city of Cameroon (Yaounde) and surrounding areas. It is one of the major centres for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in Cameroon. The pneumology service of Yaounde Jamot Hospital has 257 beds and in 2009 managed 11% of all cases of tuberculosis diagnosed in Cameroon. Approximately 1600–1800 patients with tuberculosis have been diagnosed and treated by the centre in the last 5 years. Yaounde Jamot Hospital also hosts an approved treatment centre that provides care to people living with HIV infection. Patients registered at the tuberculosis treatment centre from January to December 2009 were considered for inclusion in the study. The study was approved by the administrative authorities of Yaounde Jamot Hospital.

Definition and classification of tuberculosis cases

Patients who receive care at the centre for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis at Yaounde Jamot Hospital are consecutively registered as they are started on treatment. The approach is similar for patients with past exposure to antituberculosis treatment: those patients who report back to the centre with active tuberculosis and who have been treated in the past for at least 1 month are registered again with a new number and started on a standardised retreatment regimen. The following international definitions are applied2 3 5: (1) smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB+): acid-fast bacilli found in at least two sputum specimens; (2) smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB−): persisting negative findings on three sputum examinations after a 10-day course of non-specific antibiotic treatment in a patient with tuberculosis-like clinical and radiological signs, and in the absence of any obvious cause; (3) extra-pulmonary tuberculosis: tuberculosis involving organs other than the lungs. Patients with past exposure to antituberculosis treatment are usually smear positive2 and are further classified as ‘relapse’ (ie, reoccurrence of the disease following a successful antituberculosis treatment course), ‘failure’ (ie, positive smear after 5 months of antituberculosis treatment) and ‘treatment after default’ (ie, starting tuberculosis treatment again after 2 consecutive months of interruption). A ‘new case’ is a patient with tuberculosis who has never been exposed to antituberculosis treatment for more than 1 month in the past. ‘Other cases of tuberculosis’ refers to patients who do not fit into one of the categories described above (ie, a patient relapsing for a second time with tuberculosis, with the involved mycobacterium being sensitive to antituberculosis medication, and treated for 6 months with standard regimens).

Detection and management of HIV infection

At the centre for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis at Yaounde Jamot Hospital, all patients with tuberculosis are screened for HIV infection free of charge after informed consent has been obtained from the patient or a relative for dependant patients. This includes detection of anti-HIV 1 and anti-HIV 2 antibodies in the serum with the use of two rapid tests: the Determine HIV ½ test (Abbot Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) and the Immunocomb II HIV 1 and 2 Bispot kit (Organics, Courbevoie, France). A patient is classified as HIV positive when the two tests are positive. For discordant tests, a confirmatory Western blot test (New Lav Blot; Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Chaska, Minnesota, USA) is conducted. All HIV-positive patients are started on prophylaxis with cotrimoxazole, while those with a CD4 lymphocyte count <200/mm3 (or <15% of the total lymphocyte count in those <15 years of age) are started on triple antiretroviral therapy free of charge. Initial antiretroviral regimens consist of the combinations lamivudine–zidovudine–efavirenz or lamivudine–stavudine–efavirenz.

Tuberculosis treatment

Tuberculosis treatment at the centre is based on the DOT approach, in accordance with the guidelines of the Cameroon National Programme against Tuberculosis and the WHO recommendations.2 3 Patients are admitted during the intensive phase of antituberculosis treatment or are treated as outpatients. Antituberculosis drugs are dispensed free of charge to all patients. Category I treatment regimens are used for new patients and category II regimens for retreatment cases. New cases are treated with a regimen that includes an intensive 2-month phase with rifampicin (R), isoniazid (H), ethambutol (E) and pyrazinamide (Z), followed by a 4-month continuation phase with rifampicin and isoniazid. During retreatment, streptomycin (S) is added to category I medications (R, H, E, Z). Therefore, retreatment cases are treated with RHEZS for 2 months, followed by 1 month on RHEZ and 5 months on RHE. During the intensive phase, adherence is directly monitored by the healthcare team for admitted patients, and during weekly drug collection for outpatients. The continuation phase is conducted on an outpatient basis and adherence assessed during monthly drug collection visits.

Monitoring and outcomes of tuberculosis treatment

During antituberculosis treatment, PTB+ patients are re-examined for acid-fast bacilli at the end of months 2, 5 and 6 for new cases, and at the end of months 3, 5 and 8 in case of retreatment. PTB− patients and those with extra-pulmonary tuberculosis are monitored clinically and/or radiologically at the same frequency. At the end of treatment, patients are ranked into mutually exclusive categories2 as: (1) cured: the patient has a negative smear in the last month of treatment and in least one of the preceding months; (2) treatment completed: the patient has completed the treatment but does not have a smear result for the end of the last month; (3) failure: the patient has at least two positive smears at the 5th month or later during treatment; (4) death: death from any cause during treatment; (5) defaulter: a patient whose treatment has been interrupted for at least 2 consecutive months; and (6) transfer: the patient has been transferred to complete treatment in another centre and their treatment outcome is unknown.

Data collection

Data for the study were collected from the tuberculosis treatment registers and antituberculosis treatment forms of the tuberculosis treatment centre at Yaounde Jamot Hospital. Data were collected on age, sex, residence (urban vs rural), history of exposure to antituberculosis treatment, site of tuberculosis infection, status for HIV infection, CD4 lymphocyte count (in those with HIV infection), intensive antituberculosis treatment setting (hospital vs ambulatory), outcome of tuberculosis treatment and time to treatment discontinuation. Cure and tuberculosis treatment completion were considered favourable outcomes (successful treatment) while death, default and failure were considered unfavourable outcomes.10

Statistical methods

Data were analysed using SPSS V.12.0.1 for Windows (SPSS) and SAS/STAT V.9.1 for Windows (SAS Institute). Results are presented as counts (proportions) and medians (IQR). Group comparisons used the χ2 test and equivalents for qualitative variables, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) and equivalents for quantitative variables. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to relate baseline characteristics to treatment discontinuation during follow-up. Exploratory analyses were adjusted for age and sex, and then all significant predictors identified (p<0.05) were entered into the same multivariable model adjusted for sex and age. All Cox models were stratified by type of patient (ie, new patient, retreatment) to account for differences in the duration of treatment. The Kaplan–Meier estimator was also used to depict the probability of treatment discontinuation across strata of significant predictors, and group comparisons were made using the log-rank test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population and antituberculosis treatment discontinuation rate

Between January and December 2009, 1688 patients with tuberculosis were registered at the centre for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. Their demographic details, clinical profiles and outcomes are summarised in table 1. Their median age was 32 years (IQR 25–42 years) and 954 (56.5%) were men. There were 1231 (73%) cases of PTB+, 168 (10%) of PTB− and 289 (17%) of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. The cumulative incidence rate of antituberculosis treatment discontinuation was 20% and the treatment success rate was 68.4%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with tuberculosis according to treatment outcome at Yaounde Jamot Hospital in 2009

| Characteristics | Categories | Total | Outcomes of tuberculosis treatment |

|||||

| Success* | Failure | Death | Defaulted | Transferred | p Value | |||

| N (%) | 1688 | 1155 (68.4) | 6 (0.4) | 86 (5.1) | 337 (20.0) | 104 (6.2) | ||

| Age, years | ≤15 | 39 (2.3) | 33 (84.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (12.8) | 1 (2.6) | <0.031 |

| >15–59 | 1554 (92.1) | 1067 (68.7) | 5 (0.3) | 75 (4.8) | 310 (19.9) | 97 (6.2) | ||

| ≥60 | 95 (5.6) | 55 (57.9) | 1 (1.1) | 11 (11.6) | 22 (23.2) | 6 (6.3) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 32 (25–42) | 32 (24–42) | 35 (26–48) | 45 (32–54) | 32 (25–42) | 35.5 (24–42) | <0.001 | |

| Men | 954 (56.5) | 650 (68.1) | 4 (0.4) | 50 (5.2) | 195 (20.4) | 55 (5.8) | 0.882 | |

| Residence | Urban | 1423/1662 (85.6) | 995 (69.9) | 5 (0.4) | 72 (5.1) | 283 (19.9) | 68 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 239/1662 (14.4) | 144 (60.3) | 1 (0.4) | 13 (5.4) | 47 (19.7) | 34 (14.2) | ||

| Place of screening | This centre | 1625 (96.3) | 1115 (68.6) | 6 (0.4) | 84 (5.2) | 319 (19.6) | 101 (6.2) | 0.269 |

| Elsewhere | 63 (3.7) | 40 (63.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.2) | 18 (28.6) | 3 (4.8) | ||

| Setting of intensive phase of treatment | Hospitalisation | 1098 (65.0) | 772 (70.3) | 3 (0.3) | 69 (6.3) | 179 (16.3) | 75 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| Outpatient | 590 (35.0) | 383 (64.9) | 3 (0.5) | 17 (2.9) | 158 (26.8) | 29 (4.9) | ||

| Clinical forms | PTB+ | 1231 (72.9) | 860 (69.9) | 6 (0.5) | 16 (4.5) | 239 (19.4) | 70 (5.7) | 0.012 |

| PTB− | 168 (10.0) | 95 (56.5) | 0 (0) | 16 (9.5) | 45 (26.8) | 12 (7.1) | ||

| ETB | 289 (17.1) | 200 (69.2) | 0 (0) | 14 (4.8) | 53 (18.3) | 22 (7.6) | ||

| Type of patient | New cases | 1543 (91.4) | 1059 (68.6) | 5 (0.3) | 81 (5.2) | 299 (19.4) | 99 (6.4) | 0.20 |

| Retreatment cases | 145 (8.6) | 96 (66.2) | 1 (0.7) | 5 (3.4) | 38 (26.2) | 5 (3.4) | ||

| HIV serology | Not done | 241 (14.3) | 122 (50.6) | 2 (0.8) | 20 (8.3) | 72 (29.9) | 25 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| Negative | 942 (55.8) | 703 (74.6) | 4 (0.4) | 17 (1.8) | 166 (18) | 50 (5.4) | ||

| Positive | 497/1419 (35) | 330 (65.3) | 0 (0) | 49 (9.7) | 97 (19.2) | 29 (5.7) | ||

| Sputum smear conversion† | Yes | 1378/1471 (93.7) | 1072 (77.8) | 0 (0) | 13 (0.9) | 229 (16.6) | 64 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 93/1471 (6.3) | 77 (82.8) | 4 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 10 (10.8) | 2 (2.2) | ||

Data are number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Treatment success indicates cured+completed.

At the end of the intensive phase (applicable only to patients with smear-positive tuberculosis).

ETB, extra-pulmonary tuberculosis; PTB+, smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis; PTB−, smear negative pulmonary tuberculosis.

Time to tuberculosis treatment discontinuation

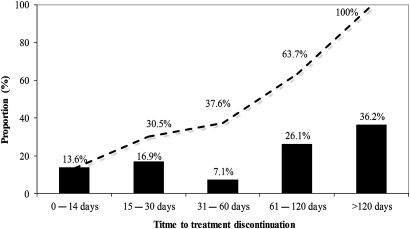

Antituberculosis treatment interruption in 210 patients (62.3%) occurred during the continuation phase of treatment (figure 1) and the median (IQR) time to tuberculosis treatment discontinuation was 90 days (30–150). Tuberculosis treatment discontinuation was more likely to occur during the continuation phase in those hospitalised during the intensive phase than in those treated as outpatients (134 (74.9%) vs 77 (48.7%); p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Time to treatment discontinuation.

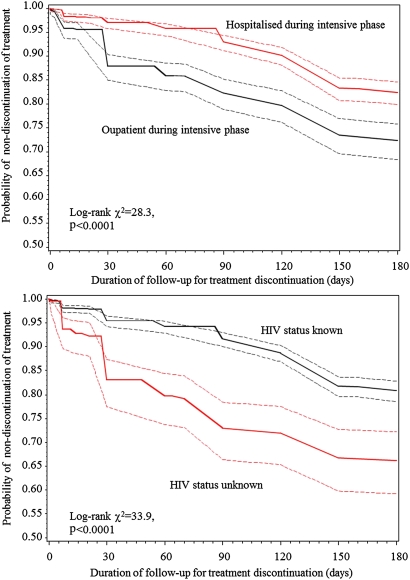

Determinants of treatment discontinuation

The probability of treatment discontinuation according to intensive treatment setting and whether an HIV test had been carried out is shown in figure 2. At each time point during follow-up, the probability of treatment discontinuation was always lower in patients hospitalised during the intensive treatment phase than in those treated as outpatients during the intensive phase. Similarly, the probability of discontinuation was always lower in patients with known status for HIV infection than in those with unknown status.

Figure 2.

Duration of follow-up for treatment discontinuation (days).

Cox regression models were used to examine predictors of treatment discontinuation using the observed follow-up period for all participants in the cohort. In models adjusted for age and sex, hospitalisation during the intensive phase reduced the risk of treatment discontinuation (HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.46 to 0.72), while having PTB− (1.59; 1.15 to 2.21) or unknown status for HIV infection (1.28; 1.17 to 1.41) significantly increased the risk of treatment discontinuation. Following further adjustment for those variables that were significant in basic models, ambulatory treatment during the intensive phase and unknown status for HIV infection were the main determinants of antituberculosis treatment discontinuation (table 2).

Table 2.

HRs and 95% CIs for predictors of antituberculosis treatment discontinuation from Cox regression analysis

| Characteristics | Basic models |

Final models |

||

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age (per year) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.01) | 0.121 | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.01) | 0.133 |

| Sex (women vs men) | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.20) | 0.723 | 0.99 (0.79 to 1.23) | 0.922 |

| Hospitalised intensive phase | 0.58 (0.46 to 0.72) | <0.0001 | 0.69 (0.54 to 0.89) | 0.004 |

| Residence (urban vs rural) | 0.92 (0.67 to 1.26) | 0.596 | – | – |

| Clinical form of tuberculosis | ||||

| Positive smear (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Negative smear | 1.59 (1.15 to 2.21) | 0.005 | 1.25 (0.89 to 1.76) | 0.192 |

| Extra-pulmonary | 0.99 (0.73 to 1.34) | 0.948 | 0.96 (0.71 to 1.30) | 0.780 |

| Unknown status for HIV | 1.28 (1.17 to 1.41) | <0.0001 | 1.65 (1.24 to 2.21) | 0.0007 |

Basic models are adjusted for age and sex, and final models are further adjusted for all significant predictors in the basic models.

All Cox models are stratified by type of patient (ie, new patient, retreatment) to account for differences in the duration of treatment.

Discussion

In this study, we have assessed the incidence of antituberculosis treatment discontinuation and predictors of treatment discontinuation in a large cohort of patients treated for tuberculosis in a major referral centre in Cameroon. The treatment success rate was 68.4% and the cumulative incidence of treatment discontinuation was 20% overall and 19.4% among patients with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Discontinuation was most likely to occur during the continuation phase of treatment and mostly among those treated as outpatients during the intensive phase and among patients with unknown status for HIV infection.

Treatment discontinuation in our study was based on the WHO's definition, which characterises a defaulter as a patient whose treatment has been discontinued for at least 2 consecutive months.2 Compared with the few other studies from Africa that have used similar definitions, the discontinuation rate in our cohort was similar to that reported by Shargie et al in South Ethiopia,11 lower that that found by Kaona and colleagues in Zambia,12 and higher than that reported by Tekle et al in Arsi in Ethiopia.13 These studies, however, differ from our study in a number of respects. The largest of the studies had 20% fewer patients than our cohort,13 while the other two had less than a quarter of the number of participants in our sample.11 12 Furthermore, the two studies in Ethiopia involved only rural participants, with one based only on patients with smear-positive tuberculosis,13 while the study in Zambia was based on a cross-sectional sample of urban dwellers.12 In general, it has been recognised that using a stricter definition for treatment discontinuation results in much higher rates than when using the WHO definition.7

Before reorganisation of the struggle against tuberculosis in Cameroon and implementation of the DOT strategy, the antituberculosis treatment discontinuation rate was 31.7% among adults with PTB+ in Yaounde Jamot Hospital.14 Our study suggests that the DOT strategy has impacted positively on antituberculosis treatment discontinuation, with a 12% drop in the discontinuation rate, although much effort is still needed to bring the rate below 10%. The currently observed discontinuation rates are twice as high as the expected rate of <10%, a requirement if the 85% antituberculosis treatment success rates prescribed in the Millennium Development Goals are to be achieved.15 Treatment discontinuation is a major challenge for programmes against tuberculosis, in that non-adherence to antituberculosis treatment is associated with reoccurrence of the disease, preservation of reservoirs for micro-organism dissemination, emergence of drug resistant species of mycobacterium and increased tuberculosis related deaths.16

Two out of three patients who defaulted from treatment in our study did so during the continuation phase of tuberculosis treatment. Predominantly late antituberculosis treatment discontinuation (ie, after the intensive phase) has also been confirmed in a systematic review.17 This late discontinuation may partly be explained by the improved condition of the patient following the intensive phase of treatment. It is possible that patients who feel clinically better following this phase are less motivated to continue treatment as they do not feel the need to do so.16

Tuberculosis treatment on an outpatient basis during the intensive phase and unknown status for HIV were the main determinants of treatment discontinuation found in our study. This suggests that direct daily supervision reduces the risk of drop out. This could be explained, at least in part, by the fact that those who receive antituberculosis treatment as inpatients during the intensive phase also receive more education about the disease, its duration and the outcome of care and are therefore more motivated to continue treatment for the required duration. Two studies from Zambia and Ethiopia have reported that poor knowledge of antituberculosis treatment duration among patients was associated with a high risk of treatment discontinuation.12 13 Unlike our results, however, another study in Spain found no protective effect of DOT on antituberculosis treatment discontinuation.18 Patients with unknown status for HIV in our study were more likely to be those who did not consent for the test, since cost is not a constraint for HIV screening in our setting. It is possible that faced with the persisting invitation from healthcare personnel to accept HIV screening, some of the non-consenting patients would prefer to stop the antituberculosis treatment and walk away from the programme. The stigmatisation of people living with HIV is a reason for not consenting for screening.19 20 We also speculate that antituberculosis treatment discontinuation is not the direct consequence of not consenting for HIV screening, but that the latter is just an indicator of the profile of those patients who will adhere less to any medical prescription. The effects of non-consenting for HIV screening on antituberculosis treatment discontinuation have not been investigated by other studies.7 In agreement with a previous study in Cameroon,14 and unlike findings from elsewhere,11 age, gender and living in a rural area were not associated with antituberculosis treatment discontinuation in our study.

This study used administrative data routinely collected for monitoring the national programme against tuberculosis. Because such data collection is not comprehensive, we were unable to investigate the effects of some potential determinants of antituberculosis treatment discontinuation, such as the patient's knowledge about tuberculosis, the distance from the patient's residence to the tuberculosis centre, the side effects of antituberculosis treatment and chronic alcohol abuse.8 9 21–23 That no systematic effort was in place to trace patients who interrupted their treatment during the year of the study has probably introduced some biases into our ranking of patients according to the outcome of care. For instance, some patients who died in-between drug collection visits would have been inappropriately classified as defaulters, particularly among HIV infected patients.24–26 Our study also has major strengths including the large population and inclusion of forms of tuberculosis common in this setting. Unlike recent studies on this topic in Africa, assessment of predictors of treatment discontinuation used robust methods to account both for the observed time to treatment discontinuation as well as for differences in the duration of treatment for various forms of tuberculosis.7 The recent studies have either been based on patients with HIV and tuberculosis, or lacked information on status for HIV. Accordingly, none investigated the effects of HIV testing on the outcome of care for tuberculosis, as done successfully in this study.

In conclusion, antituberculosis treatment discontinuation in this setting is relatively high, and tends to occur more during the continuation phase of treatment. Patients who receive treatment on an outpatient basis during the intensive phase and those who do not consent for HIV screening are more likely to interrupt their antituberculosis treatment. Specific actions targeting these subgroups would likely improve the outcomes of care for tuberculosis in this centre. That patients treated entirely on an ambulatory basis were less like to achieve good outcomes of care as compared to those hospitalised during the intensive treatment phase, together with the much higher discontinuation rates in the same setting in the pre-DOT era, all suggest that the DOT strategy is associated with improved outcomes of care for tuberculosis in this setting. Prospective studies are needed to investigate other determinants of antituberculosis treatment discontinuation and refine the incidence data based on a more objective ascertainment of the outcomes of care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Pefura Yone EW, Kengne AP, Kuaban C. Incidence, time and determinants of tuberculosis treatment default in Yaounde, Cameroon: a retrospective hospital register-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000289. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000289

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Institutional Review Board of Yaounde Jamot Hospital.

Contributors: EWPY conceived the study, supervised data collection, co-analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. APK contributed to study design, data analysis, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. CK supervised data collection and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.WHO Tuberculosis Profile, Cameroon. https://extranet.who.int/sree/Reports (accessed 26 Jun 2011).

- 2.Aït-Khaled N, Alarcón E, Armengol R, et al. Prise en charge de la tuberculose. guide des éléments essentiels pour une bonne pratique. Sixième édn Paris: Union Internationale Contre la Tuberculose et les Maladies Respiratorires, 2010:P64 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Programme National de Lutte contre la Tuberculose Guide Technique pour le personnel de santé. 2ème édn révisée Yaoundé: Ministère de la Santé Publique du Cameroun, 2004:P40 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maartens G, Wilkinson RJ. Tuberculosis. Lancet 2007;370:2030–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organisation Mondiale de la Santé Le traitement de la tuberculose: Principes à l'intention des programmes nationaux. Troisième édn Genève: OMS, 2003:14–76 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuaban C, Bame R, Mouangue L, et al. Non conversion of sputum smear positive in new smear positive pulmonary tuberculous patients in Yaounde, Cameroon. East Afr Med J 2009;86:219–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castelnuovo B. A review of compliance to anti tuberculosis treatment and risk factors for defaulting treatment in Sub Saharan Africa. Afr Health Sci 2010;10:320–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elbireer S, Guwatudde D, Mudiope P, et al. Tuberculosis treatment default among HIV-TB co-infected patients in urban Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. Published Online First: 18 May 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1365–3156.2011.02800.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kandel TR, Mfenyana K, Chandia J, et al. The prevalence of and reasons for interruption of anti-tuberculosis treatment by patients at Mbekweni Health Centre in the King Sabata Dalindyebo (KSD) District in the Eastern Cape province. SA Fam Pract 2008;50:47 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zellweger JP, Coulon P. Outcome of patients treated for tuberculosis in Vaud County, Switzerland. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1998;2:372–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shargie EB, Lindtjorn B. Determinants of treatment adherence among smear-positive tuberculosis patients in Southern Ethiopia. PLOS medicine 2007;4:280–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaona AD, Tuba M, Siziya S, et al. An assessment of factors contributing to treatment adherence and knowledge of TB transmission among patients on TB treatment. BMC Public Health 2004;4:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tekle B, Mariam DH, Ali A. Defaulting from DOTS and its determinants in three districts of Arsi Zone in Ethiopia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002;6:573–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuaban C, Mbuntum F. Treatment outcome and risk factors for default in adult with pulmonary tuberculosis in Yaounde, Cameroon. Health Sci Dis 2002;1:5–9 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resolution WHA44.8 Tuberculosis control programme. In: Handbook of resolutions and decisions of the World Health Assembly and the Executive Board. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1993:116 (WHA44/1991/REC/1). [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Best Practice for the Care of Patients with Tuberculosis. Paris: USAID, 2007:P51 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruk ME, Schwalbe NR, Aguiar CA. Timing of default from tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2008;13:703–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caylà JA, Rodrigo T, Ruiz-Manzano J, et al. ; Working Group on Completion of Tuberculosis Treatment in Spain (Study ECUTTE) Tuberculosis treatment adherence and fatality in Spain. Respir Res 2009;10:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.UNAIDS "HIV and AIDS-related Stigmatisation, Discrimination and Denial: Forms, Contexts and Determinants," Research Studies from Uganda and India (prepared for UNAIDS by Peter Aggleton). Geneva:UNAIDS, 2000:1–28 [Google Scholar]

- 20.USAID Breaking the Cycle: Stigma, Discrimination, Internal stigma, and HIV. POLICY project (prepared for USAID by Ken Morrison). Washington, DC: USAID, 2006:1–17 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bam TS, Gunneberg C, Chamroonsawasdi K, et al. Factors affecting patient adherence to DOTS in urban Kathmandu, Nepal. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006;10:270–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang KC, Leung CC, Tam CM. Risk factors for defaulting from antituberculosis treatment under directly observed treatment in Hong Kong. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8:1492–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelmanova IY, Keshavjee S, Golubchikova VT, et al. Barriers to successful tuberculosis treatment in Tomsk, Russian Federation: non-adherence, default and the acquisition of multidrug resistance. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:703–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castelnuovo B, Hermans S, Park R, et al. Evaluation of the Impact of TB-HIV Integrated Care in Reducing the Proportion of Patients Defaulting Anti TB Treatment in a Large Urban HIV Clinic in Kampala, Uganda [abstract]. IAS, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalal RP, Macphail C, Mqhayi M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of adult patients lost to follow-up at an antiretroviral treatment clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;47:101–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2009;4:e5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.