Abstract

Background

Tobacco use is a major risk factor for recurrent stroke. The provision of cost-free quit smoking medications has been shown to be efficacious in increasing smoking abstinence in the general population.

Objective

The objective of this pilot study was to assess the feasibility and obtain preliminary data on the effectiveness of providing cost-free quit smoking pharmacotherapy and counselling to smokers identified in a stroke prevention clinic.

Trial design

Cluster randomised controlled trial.

Methods

All patients seen at the Ottawa Hospital Stroke Prevention Clinic who smoked more five or more cigarettes per day, were ready to quit smoking in the next 30 days, and were willing to use pharmacotherapy were invited to participate in the study. All participants were advised to quit smoking and treated using a standardised protocol including counselling and pharmacotherapy. Participants were randomly assigned to either a prescription only usual care group or an experimental group who received a 4-week supply of cost-free quit smoking medications and a prescription for medication renewal. All patients received follow-up counselling. The primary outcome was biochemically validated quit rates at 26 weeks. The research coordinator conducting outcome assessment was blind to group allocation.

Results

Of 219 smokers screened, 73 were eligible, 28 consented and were randomised, and 25 completed the 26-week follow-up assessment. All 28 patients randomised were included in the analysis. The biochemically validated 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate in the experimental group compared to the usual care group was 26.6% vs 15.4% (adjusted OR 2.00, 95% CI 0.33 to 13.26; p=0.20).

Conclusions

It would be feasible to definitively evaluate this intervention in a large multi-site trial.

Trial registration number

http://ClinicalTrials.gov # UOHI2010-1.

Article summary

Article focus

To assess the feasibility of and obtain preliminary data on the effectiveness of providing cost-free quit smoking pharmacotherapy and counselling to smokers identified in a stroke prevention clinic.

Key messages

This pilot study provides preliminary data to inform the design of a larger study to assess the efficacy of providing cost-free quit smoking medications to smokers with transient ischaemic attack (TIA) and stroke.

The study was underpowered to achieve statistically significant results.

It would be feasible to definitively evaluate this intervention in a large multi-site trial.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first study to examine the efficacy of providing a starter kit of cost-free pharmacotherapy to patients at high risk of stroke who are ready to quit smoking.

The strengths of this study include the randomised control trial design.

The study also provides previously unavailable descriptive information on smokers with TIA and stroke.

The study limitations include the small sample size, a 40% rate of patient enrolment and the fact that study participants were from a single stroke prevention clinic, which may limit generalisability.

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is a major independent risk factor for recurrent stroke and has been identified as an important treatment target for all patients at high risk of future stroke.1–4 Stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA) patients who quit smoking reduce their relative risk of stroke recurrence by 50%.5 Smoking cessation is also associated with a reduction in stroke related hospitalisations.6 7 Unfortunately, most smokers with cerebrovascular disease have difficulty quitting on their own. Previous research has documented that approximately 80–90% of stroke and TIA patients identified as smokers at the time of their event continued to use tobacco 6–12 months later.8–10

Evidence from placebo-controlled clinical trials consistently demonstrates that cessation medications such as nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion and varenicline combined with counselling, can double or triple long-term smoking abstinence in smokers.11–13 Consequently, stroke prevention guidelines recommend that healthcare providers strongly advise every smoker who is at high risk for a stroke or TIA to quit, and provide specific assistance with quitting, including counselling and pharmacotherapy.14 15 Despite the evidence supporting the importance of smoking cessation, there is a well documented practice gap in the rates at which smoking cessation is addressed by healthcare professionals, even for high risk groups such as TIA patients and/or stroke survivors.8–10

Sub-optimal use of evidence-based quit smoking medications and premature discontinuation of pharmacotherapy has been linked to poorer rates of smoking abstinence.16 17 Although reasons for poor adherence are varied, financial barriers are a major determinant for non-use and non-adherence.18 19 The provision of cost-free medications has been shown to improve motivation to quit and increase quit attempts and smoking abstinence in the general population; no study, however, has examined the efficacy of providing cost-free cessation pharmacotherapy to patients who have recently experienced a TIA or stroke or are at high risk for stroke.20–23

Given that a high incidence of stroke has been reported among lower socioeconomic groups, it is hypothesised that making cost-free medications available to patients who receive standardised smoking cessation interventions will enhance patient quit attempts, remove barriers related to the cost of pharmacotherapy, and enhance compliance with the full course of pharmacotherapy among patients and lead to increased success with quitting.24 25 The low quit rates documented among patients who have experienced TIA or stroke, supports the need to determine the efficacy of interventions which may enhance cessation in this high risk group of smokers.8–10 Moreover, the high risk of a recurrent event among stroke patients who continue to smoke suggests the cost-benefit of providing cost-free pharmacotherapy may be realised in a relatively short time frame, which may justify providing coverage to this group of high risk smokers.6 As such, the purpose of this pilot study was to test feasibility and obtain effect estimates to inform the design of a larger definitive study on the effectiveness of providing cost-free quit smoking pharmacotherapy and counselling to smokers identified in a specialty stroke prevention clinic compared to the provision of a conventional prescription for pharmacotherapy.26

Methods

Design

This pilot study was a two-group, open label, experimental feasibility study with random assignment to either a prescription-only usual care group (PO group) or a cost-free quit smoking medications group (CF group). The primary outcome was biochemically validated quit rates at 26 weeks. Secondary outcome measures included patient quit attempts at 26 weeks and adherence to quit smoking counselling and pharmacotherapy protocols. Levels of eligibility, consent, adherence and retention were used as indicators of study feasibility. The study protocol was approved by the University of Ottawa Heart Institute Human Research Ethics Board.

Setting and patient population

Patients were recruited from The Ottawa Hospital Stroke Prevention Clinic, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada over an 18-month period. The clinic provides assessment and secondary prevention services to patients who have recently experienced a TIA or stroke or have been identified as being at high risk for a cerebrovascular event.

Sample size

It was estimated that a total of 70 patients would be enrolled over the 18-month recruitment period based on the assumption that 200 smokers were seen at the clinic in the previous year and 25% were estimated to be eligible and willing to participate. It was hypothesised that a 5–10% increase in smoking abstinence would be documented in the CF group compared to the PS group based on trials in the general population.20–23 It was understood that the trial would not be powered to detect significant differences between groups.

Standardised smoking cessation protocol

As part of the study, a systematic approach to the identification and treatment of patients who smoke was introduced into routine clinic practice at the Stroke Prevention Clinic; the protocol was based on the Ottawa Model for Smoking Cessation.27 28 The nurse specialists and neurologists providing care in this setting were provided with training sessions in evidence-based smoking cessation interventions. Patient and provider tools and resources, adapted from the Ottawa Model for Smoking Cessation, were introduced in the stroke clinic to facilitate and support the standardised delivery of tobacco treatment. This included a waiting room screening form, a consult form to support clinicians in the delivery of cessation interventions, and a quit plan for patients ready to quit smoking.

The waiting room screening form which assessed current smoking status was distributed to all patients upon registration at the clinic. Patients were instructed to return the screening form to the clerk when completed. The screening nurse used the results obtained in the screening process to flag all patient charts indicating whether the patient was a smoker or non-smoker. A smoking cessation consult form was placed on the chart of each patient identified as a smoker by the clerk and served as a prompt to the neurologist for delivering evidence-based smoking cessation interventions. The neurologist then provided strong, unambiguous, non-judgemental advice to quit to all smokers along with an offer of support with making a cessation attempt. The neurologist also assessed patient readiness to quit in the next 30 days and documented patient response on the consult form.

Eligibility screening

Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they reported smoking an average of five or more cigarettes per day in the past 3 months, were 18 years of age or older, were willing to set a quit date in the next 30 days, and were willing to use a quit smoking medication. Patients who were unable to read and understand English or French or who had contraindications to all approved smoking cessation medications (nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion and varenicline) were excluded from the study. Eligible patients were invited by the neurologist or the stroke prevention nurse specialist to take part in the study. Eligible patients interested in participating in the study had the study procedures explained to them by the research study coordinator. All participants provided informed consent.

Allocation to treatment

Patients were randomly assigned to one of two intervention groups. The research coordinator or clinic nurse specialist opened a sealed envelope which contained the treatment group allocation. Randomisation envelopes were prepared by a third party using a random numbers table blocked in groups of four and sealed until treatment allocation. Due to the nature of the intervention, participants and clinicians were not blinded to their intervention assignment.

Comparison groups

Cost-free pharmacotherapy experimental group (CF group)

Participants assigned to the CF group received a starter kit (4-week supply) of cost-free quit smoking medication (nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion or varenicline) and a pre-printed prescription to be filled by the patient at the end of the 4 weeks.

Prescription only usual care group (PO group)

Participants assigned to the prescription only usual care group received a prescription for smoking cessation pharmacotherapy to be filled at their own cost at their local community pharmacy.

Patient quit plan consultation and telephone follow-up support

The stroke prevention nurse specialist conducted a 10–20 min consultation with all study participants using a standardised consult form and patient education materials. During the consult discussion, the nurse specialist addressed patient concerns about quitting, set a target quit date (TQD) with the patient in the next 30 days, developed strategies for addressing cravings and withdrawal, and identified strategies for relapse prevention and management. Patients were then prescribed a first-line quit smoking pharmacotherapy. The choice of the pharmacotherapy was based on patient preference and smoking history. All study participants were contacted by phone by a trained smoking cessation counsellor 7 days before their TQD, and 5, 14, 30, 90 and 180 days after to discuss the patient's quit smoking progress, address potential concerns and assist with relapse prevention strategies and management. During the call, the smoking cessation nurse specialist posed a series of questions concerning: current smoking status; confidence in staying smoke-free until the next planned call; and the use of pharmacotherapy, self-help materials and other forms of cessation support.

Post-assessment and follow-up data collection

All participants were contacted by telephone 26 weeks (±2 weeks) after their TQD to assess outcome measures. All patients reporting smoking abstinence had an end-expired carbon monoxide (CO) sample collected in order to validate smoking abstinence.

Outcome measures

The dependent variables of primary interest were measured at 26 weeks and included: (1) biochemically confirmed 7-day point prevalence abstinence; and (2) continuous abstinence since TQD. Participants who were not available for follow-up were considered smokers. At the 26-week follow-up, all patients who reported being abstinent from smoking had their smoking status confirmed by measurement of a CO sample. If any CO was >10 ppm, the subject was considered a smoker. At the 26-week follow-up assessments, patient quit attempts in the previous 6 months of 24 h or longer were documented. During the 26-week telephone follow-up assessment, patient adherence with pharmacotherapy was assessed by evaluating the number of doses of pharmacotherapy consumed within the prescribed study interval. The telephone counsellor recorded the completion of all seven counselling sessions in order to assess patient adherence.

Analysis

Descriptive characteristics were assessed for all smokers screened at the stroke prevention clinic during the recruitment period. Baseline characteristics of study participants assigned to each of the intervention groups were compared using independent t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables to assess any chance imbalances that may have occurred. A logistic regression model was fitted to 26-week abstinence status (smoker or non-smoker) and treatment group included as the independent variable. Adjusted analyses were conducted to account for baseline differences between groups. Treatment adherence and patient quit attempts were also compared between treatment groups. All patients were included in the intention to treat analysis. Missing data were categorised as active smoking (smoking abstinence), not having made a quit attempt (quit attempts) or non-compliant with medications (adherence).

Results

Participant recruitment and data collection

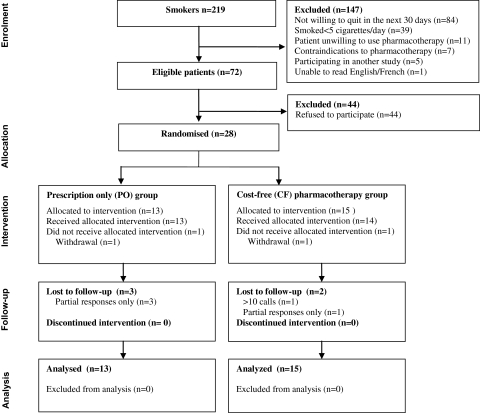

Figure 1 presents the CONSORT diagram for data collection flow. There were 2182 patient visits at the Stroke Prevention Clinic between August 2008 and December 2009 and 219 unique patients were identified as having used tobacco in the last 7 days. Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of all patients screened at the Stroke Prevention Clinic who reported active smoking during the study recruitment period. At the initial screening, 74% of smokers reported they were planning on quitting smoking within the next 6 months and 36% were planning on quitting in the next 30 days. A total of 147 patients who smoked did not meet eligibility criteria. The primary reason for exclusion was the patient not being willing to quit smoking in the next 30 days and smoking less than an average of five cigarettes per day. An additional 14 patients were not willing to use pharmacotherapy. Among eligible patients, 29/73 (40%) agreed to participate in the study. Study participants were more likely than non-participants to be younger, to smoke more cigarettes per day, and to be concerned about withdrawal and stress, and less concerned about boredom. Two study participants withdrew from the study. The 26-week follow-up data were complete for 25/28 (89%) study participants. There were no significant differences in loss to follow-up between intervention groups.

Figure 1.

CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of smokers screened and study participants

| Parameter | Smokers screened (n=219) | Eligible non-participants (n=44) | Study participants (n=28) | PO group (n=13) | CF group (n=15) | p Value* |

| Age, mean (SD) | 55.4 (12.8) | 59.4 (9.8) | 54.5 (10.5) | 53.5 (8.1) | 55.4 (12.4) | 0.65 |

| % Male | 48.8 | 61.4 | 60.7 | 69.2 | 53.3 | 0.39 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 12.1 (3.1) | 11.6 (4.2) | 11.7 (3.4) | 12.9 (2.3) | 10.6 (4.0) | 0.08 |

| Cigarettes/day, mean (SD) | 15.1 (10.4) | 16.9 (10.6) | 17.5 (8.0) | 20.7 (8.8) | 14.8 (6.2) | 0.05 |

| Years smoking cigarettes, mean (SD) | 33.3 (15.0) | 34.7 (13.6) | 34.6 (14.5) | 32.5 (15.1) | 36.4 (14.1) | 0.49 |

| Time to first cigarette | ||||||

| % Within 30 min of waking | 67.3 | 72.2 | 78.5 | 77.0 | 80.0 | 0.87 |

| % More than 30 min after waking | 32.7 | 27.8 | 21.5 | 23.0 | 20.0 | |

| Confidence (SD)† | 5.4 (3.3) | 6.1 (3.4) | 6.2 (3.1) | 5.0 (3.2) | 7.3 (2.6) | 0.05 |

| Importance of quitting (SD)‡ | 7.2 (3.3) | 7.5 (3.2) | 8.3 (2.4) | 8.6 (2.7) | 7.9 (2.3) | 0.47 |

| Quit attempts | ||||||

| None | 41.3 | 53.2 | 35.7 | 30.8 | 40.0 | 0.78 |

| 1 or 2 | 36.0 | 18.4 | 39.3 | 46.2 | 33.3 | |

| 3 or more | 22.7 | 26.3 | 25.0 | 23.1 | 26.7 | |

| Readiness to quit at initial screening§ | ||||||

| Next 30 days | 40.4 | 54.5 | 70.4 | 84.6 | 57.1 | 0.12 |

| Next 6 months | 59.6 | 45.5 | 29.6 | 15.4 | 42.9 | |

| Other smoker in the home | 45.3 | 51.3 | 46.4 | 53.8 | 40.0 | 0.35 |

| Medication coverage | ||||||

| Yes | 18.2 | 15.9 | 32.1 | 38.5 | 26.7 | 0.62 |

| No | 49.4 | 45.4 | 32.1 | 23.1 | 40.0 | |

| Don't know | 32.4 | 38.7 | 35.7 | 38.5 | 33.3 | |

| HADS score¶ | ||||||

| Anxiety, mean (SD) | – | – | 7.0 (3.8) | 6.8 (3.8) | 7.1 (3.9) | 0.88 |

| Depression, mean (SD) | – | – | 5.1 (4.1) | 5.5 (2.8) | 4.7 (4.9) | 0.64 |

| Reasons for quitting | ||||||

| Health reasons | 81.9 | 77.8 | 93.1 | 92.3 | 93.8 | 0.88 |

| Family | 20.6 | 16.7 | 34.5 | 38.5 | 31.3 | 0.68 |

| Financial | 20.5 | 19.4 | 20.7 | 23.1 | 18.8 | 0.78 |

| Social | 11.9 | 11.4 | 13.8 | 15.4 | 12.5 | 0.82 |

| Concerns about quitting | ||||||

| Stress | 53.3 | 43.2 | 62.1 | 46.2 | 75.0 | 0.11 |

| Withdrawal | 35.3 | 38.6 | 48.3 | 53.8 | 43.8 | 0.59 |

| Weight | 29.4 | 25.0 | 37.9 | 38.5 | 37.5 | 0.96 |

| Boredom | 18.2 | 13.6 | 24.1 | 23.1 | 25.0 | 0.90 |

| Social | 9.6 | 9.1 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 0.36 |

Comparisons are based on the Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables and Student t test for continuous variables between intervention groups.

On a scale of 1–10, how confident are you that you would be able to quit smoking at this time? (1=not at all confident, 10=extremely confident).

On a scale of 1–10, how important is it to you to quit smoking at this time? (1=not important at all, 10=extremely important).

Response provided on the waiting room screening form to the question: ‘Which of the following best describes your feelings about smoking right now?’ Patients' readiness to quit was reassessed following strong personalised advice from the neurologists to quit.

HADS scores: 0–7=normal; 8–10=borderline abnormal; 11–21=abnormal.29

CF, cost-free pharmacotherapy; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PO, prescription only.

Participant characteristics

A total of 28 eligible smokers (mean age 54.5±10.5 years, 70% male) were enrolled in the pilot study. The characteristics of study participants are presented in table 1. CF participants reported smoking significantly more cigarettes per day as well as significantly greater self-efficacy (confidence) with quitting compared to participants randomised to the PO group.

Smoking abstinence

Table 2 presents the effect estimates for smoking abstinence. Quit rates were 33.3% in the CF group versus 15.4% in the PO group for 7-day point prevalence abstinence and 23.1% compared to 15.4% for continuous abstinence at 26 weeks. Effect estimates were adjusted to account for the observed differences between groups. The adjusted OR for self-reported continuous abstinence was 5.51 (95% CI 0.44 to 69.3; p=0.186) and 7-day point prevalence abstinence was 2.25 (95% CI 0.25 to 20.4; p=0.470). Observed differences between groups were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

26-Week smoking abstinence

| 6-Month abstinence measure | PO group, n/N (%) | Cost-free group, n/N (%) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | p Value* |

| Continuous abstinence | 2/13 (15.4) | 5/15 (33.3) | 2.75 (0.43 to 17.5) | 0.26 | 5.51 (0.44 to 69.3) | 0.19 |

| 7-Day point prevalence abstinence | 3/13 (23.1) | 5/15 (33.3) | 1.67 (0.31 to 8.9) | 0.43 | 2.25 (0.25 to 20.4) | 0.47 |

| Biochemically validated 7-day point prevalence abstinence | 2/13 (15.4) | 4/15 (26.6) | 2.00 (0.33 to 13.3) | 0.40 | 5.95 (0.40 to 88.7) | 0.20 |

Adjusted for number of cigarettes smoked per day and self-efficacy.

CF, cost-free pharmacotherapy; PO, prescription only.

Biochemical validation of self-reported smoking abstinence was reported for 75% of patients who declared a smoke-free status at the end of 26 weeks. No differences were noted in the rates of completion of the biochemical validation at the pre- and post-intervention assessments nor were differences noted between CF and PO intervention groups (26.6% vs 15.4%). The adjusted OR for biochemically validated 7-day point prevalence abstinence was 5.95 (95% CI 0.40 to 88.7; p=0.195). Observed differences between groups were not significant.

Secondary outcomes

At the 26-week follow-up assessment, 62% of participants in the PO group reported making a quit attempt compared to 53% in the CF group. Observed differences between the groups both for use of quit smoking medications and for compliance with the full course of medication were not statistically significant. Participants in the CF group completed a mean of 6.3/7 (91%) sessions compared to 5.5/7 (78%) sessions in the PO group (see table 3).

Table 3.

Compliance with medications and quit attempts

| 6-Month abstinence measure | PO group, n/N (%) | Cost-free group, n/N (%) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | p Value* |

| Quit attempts | 8/13 (61.5) | 8/15 (53.3) | 0.71 (0.16 to 3.2) | 0.66 | 0.72 (0.12 to 4.5) | 0.72 |

| Began using medication prescribed | 8/13 (61.5) | 11/15 (73.3) | 1.7 (0.35 to 8.5) | 0.51 | 0.44 (0.03 to 5.9) | 0.54 |

| Compliance with medication >90% | 4/13 (30.7) | 7/15 (46.7) | 2.0 (0.42 to 9.3) | 0.39 | 2.2 (0.35 to 14.5) | 0.40 |

| Compliance with telephone counselling >80% | 8/13 (61.5) | 14/15 (93.3) | 8.7 (0.9 to 88.7) | 0.07 | 4.2 (0.32 to 58.9) | 0.28 |

Adjusted for number of cigarettes smoked per day and self-efficacy.

CF, cost-free pharmacotherapy; PO, prescription only.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of providing a starter kit of cost-free pharmacotherapy to patients at high risk of stroke who are ready to quit smoking. Observed differences between intervention groups for both the primary and secondary study outcomes were non-significant, and therefore a larger trial would be required to assess intervention efficacy. This pilot study found the study methods to be feasible and has provided previously unavailable data which will be used to inform sample size estimates for the design of a larger definitive trial. The study documented a much lower eligibility and participation rate than was originally hypothesised. The fact that only 40% of eligible smokers enrolled in the study suggests consideration must be given to interventions to increase patient enrolment in future investigations.

While there have been no trials to evaluate the efficacy of providing cost-free quit smoking medications to stroke or TIA patients, studies in the general population have found that the provision of cost-free smoking cessation medications increases patient motivation to quit, quit attempts and smoking abstinence.20–23 A systematic review including three trials examining the benefit of covering the cost of smoking cessation treatment (primarily the cost of pharmacotherapy) found that cost-free treatment increased the odds of achieving abstinence (OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.2 to 2.2) compared to having smokers pay for their own treatment.11 30 One additional trial, completed after the meta-analysis described above was published, found that providing cost-free effective smoking cessation pharmacotherapies to smokers in primary care increased the odds of quitting 12 months after recruitment almost fivefold (OR 4.77; 95% CI 2.0 to 11.2).23 In the present study, 15% of smokers screened had completed a university degree compared to 25.5% of smokers in the general population.31 Moreover, only 18% of smokers screened had insurance coverage for quit smoking medications. These data support the hypothesis that financial barriers may influence decisions to use pharmacotherapy among patients who have experienced TIA or stroke. Given the significant acute health benefits derived from smoking cessation among TIA and stroke patients, it would appear that this intervention program may be of particular significance for reducing disease burden and improving stroke outcomes.

Our investigation showed that a large proportion of smokers screened as part of the present study were not ready to quit smoking in the 30 days following their visit to the Stroke Prevention Clinic. The reported rate is lower than those observed in the general population despite the presence of a teachable moment resulting from a health event.11 16 This suggests that smokers identified in the stroke prevention setting represent a ‘hardened’ population of smokers, that is, those with higher levels of nicotine addiction and lack of interest in cessation.32 This is reflected by the proportion of high risk patients who were not interested in embarking upon a quit attempt in the next 30 days following strong clinician advice, and the fact that more than 65% of patients sampled reported time to first cigarette in the morning to be within 30 min of waking. Interestingly, 30% of the study sample had indicated on the waiting room screening form that they were not ready to quit in the next 30 days. However, following standardised counselling from the clinic physician, these patients decided to quit smoking and were randomised to the trial. Additional research is required to better understand the lack of intention among stroke and TIA patients to make a quit attempt and how best to motivate and/or support increased patient motivation to quit and/or harm reduction interventions such as reduce to quit approaches.

Very limited research has been published regarding smoking cessation interventions among patients with stroke or TIA. An uncontrolled prospective study examining the effects of a specific smoking cessation education intervention after stroke found that at 3 months after the event 43% of smokers had quit smoking compared with the 28% of smokers previously reported in the literature as achieving cessation after an event.33 In another study, which involved in-hospital initiation of secondary stroke prevention therapies including smoking cessation, 83% of those identified as smokers at the time of the event remained smoke free at 3-month follow-up.3 In contrast, there was no improvement in smoking quit rates of patients with stroke or TIA at 3-month follow-up after a multiple risk factor modification intervention led by a stroke nurse specialist in a single-blind randomised controlled trial.34 Given the paucity of smoking cessation trials in stroke and TIA patients, it will be particularly important for future research to investigate interventions to motivate and support cessation in this high risk population of smokers.

There are several limitations to the present study which should be considered in any interpretation of the findings. Despite positive trends, the pilot study was small and included only 28 participants, and was not able to document a significant effect of the intervention compared to control. Hence, a larger trial would be required to further explore the favourable trend documented here. In the present study all patients received access to: (1) standardised counselling; (2) a prescription for quit smoking medications while in clinic; and (3) follow-up support for 26 weeks following their scheduled quit attempt. This may be considered an enhancement over the current ‘real world’ standard of care experienced by stroke and TIA patients. The inclusion of the standardised counselling supports and pharmacotherapy may have increased the quit rates observed in both intervention groups. As the study involved the recruitment of patients from a single stroke prevention clinic, study findings may not be generalisable to the broader population of stroke and TIA patients in other settings. Only 40% of eligible patients screened consented to participate. Finally, this pilot study provided patients in the CF group with a 4-week supply of pharmacotherapy free of cost. A full course of treatment is typically 10–12 weeks. Extending the availability of the cost-free pharmacotherapy might have further enhanced study outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Papadakis S, Aitken D, Gocan S, et al. A randomised controlled pilot study of standardised counselling and cost-free pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation among stroke and TIA patients. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000366. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000366

Funding: No external funding was received for the completion of this pilot study. The two collaborating healthcare/research institutions involved in this study, the Minto Prevention and Rehabilitation Centre at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute and the Champlain Stroke Prevention Clinic provided in-kind resources to allow for the completion of the trial including the cost of the cost-free pharmacotherapy.

Competing interests: The institutions and study authors at no time received payment or services from a third party for any aspect of the work submitted. The University of Ottawa Heart Institute has received research and education grant support from Pfizer Canada, Johnson and Johnson, and GlaxoSmithKline. AP has served as a consultant and has received speaker honoraria from Pfizer, Johnson and Johnson, and GlaxoSmithKline; RR has received speaker honoraria from Pfizer; DA has received speaker honoraria from Pfizer; and DR has served as a consultant to Pfizer.

Ethics approval: The University of Ottawa Heart Institute Human Research Ethics Board provided ethics approval.

Contributors: SP, DA, SG and RR provided substantial contributions to the conception, design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the article. AP and MS contributed to the conception, design, interpretation of data and drafting of the article. DR, ML, AB, DC, DS and RE contributed to the acquisition of data, interpretation of results and drafting of the article. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The study database including participant characteristics and outcomes has been uploaded to the Dryad Digital Repository, doi:10.5061/dryad.p67jf576.

References

- 1.Shinton R, Beevers G. Meta-analysis of relation between cigarette smoking and stroke. BMJ 1989;298:789–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, et al. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for stroke. The Framingham Study. JAMA 1988;259:1025–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, et al. Smoking cessation in relation to total mortality rates in women. A prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:992–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ovbiagele B, Saver JL, Fredieu A, et al. In-hospital initiation of secondary stroke prevention therapies yields high rates of adherence at follow-up. Stroke 2004;35:2879–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Whincup PH, et al. Smoking cessation and the risk of stroke in middle-aged men. JAMA 1995;274:155–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lightwood JM, Glantz SA. Short-term economic and health benefits of smoking cessation: myocardial infarction and stroke. Circulation 1997;96:1089–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naidoo B, Stevens W, McPherson K. Modelling the short term consequences of smoking cessation in England on the hospitalisation rates for acute myocardial infarction and stroke. Tob Control 2000;9:397–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mouradian MS, Majumdar SR, Senthilselvan A, et al. How well are hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and smoking managed after a stroke or transient ischemic attack? Stroke 2002;33:1656–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bak S, Sindrup SH, Alslev T, et al. Cessation of smoking after first-ever stroke: a follow-up study. Stroke 2002;33:2263–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson P, Rosewell M, James MA. How good is the management of vascular risk after stroke, transient ischaemic attack or carotid endarterectomy? Cerebrovasc Dis 2007;23:156–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:158–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(1):CD000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. ; on behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 2011;42:227–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindsay MP, Gubitz G, Bayley M, et al. ; On behalf of the Canadian Stroke Strategy Best Practices and Standards Writing Group. Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for Stroke Care (Update 2010). Ottawa, Ontario Canada: Canadian Stroke Network, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ismailov RM, Leatherdale ST. Smoking cessation aids and strategies among former smokers in Canada. Addict Behav 2010;35:282–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balmford J, Borland R, Hammond D, et al. Adherence to and reasons for premature discontinuation from stop-smoking medications: data from the ITC Four-Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:94–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smeeth L, Fowler G. Nicotine replacement therapy for a healthier nation. Nicotine replacement is cost effective and should be prescribable on the NHS. BMJ 1998;317:1266–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogt F, Hall S, Marteau TM. Understanding why smokers do not want to use nicotine dependence medications to stop smoking: qualitative and quantitative studies. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:1405–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummings KM, Fix B, Celestino P, et al. Reach, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of free nicotine medication giveaway programs. J Public Health Manag Pract 2006;12:37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings KM, Hyland A, Fix B, et al. Free nicotine patch giveaway program 12-month follow-up of participants. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:181–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaper J, Wagena EJ, Willemsen MC, et al. Reimbursement for smoking cessation treatment may double the abstinence rate: results of a randomized trial. Addiction 2005;100:1012–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twardella D, Brenner H. Effects of practitioner education, practitioner payment and reimbursement of patients' drug costs on smoking cessation in primary care: a cluster randomised trial. Tob Control 2007;16:15–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox AM, McKevitt C, Rudd AG, et al. Socioeconomic status and stroke. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:181–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arrich J, Mu¨llner M, Lalouschek W, et al. Influence of socioeconomic status and gender on stroke treatment and diagnostics. Stroke 2008;39:2066–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why, and how. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid RD, Mullen KA, Slovinec D'Angelo ME, et al. Smoking cessation for hospitalized smokers: an evaluation of the “Ottawa Model”. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reid RD, Pipe AL, Quinlan B. Promoting smoking cessation during hospitalization for coronary artery disease. Can J Cardiol 2006;22:775–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crawford JR, Henry JD, Crombie C, et al. Normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2001;40:429–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reda AA, Kaper J, Fikrelter H, et al. Healthcare financing systems for increasing the use of tobacco dependence treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD004305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reid JL, Hammond D, Driezen P. Socio-economic status and smoking in Canada, 1999–2006: has there been any progress on disparities in tobacco use? Can J Public Health 2010;101:73–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costa ML, Cohen JE, Chaiton MO, et al. “Hardcore” definitions and their application to a population-based sample of smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:860–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauerbeck LR, Khoury JC, Woo D, et al. Smoking cessation after stroke: education and its effect on behavior. J Neurosci Nurs 2005;37:316–19, 325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellis G, Rodger J, McAlpine C, et al. The impact of stroke nurse specialist input on risk factor modification: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2005;34:389–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.