Abstract

Background

Mini-sternotomy for isolated aortic valve replacement aims to reduce operative trauma hastening recovery and improving the cosmetic outcome of cardiac surgery. The short-term clinical benefits from the mini-sternotomy are presumed to arise because the incision is less extensive and the lower half of the chest cage remains intact. The basic conduct of virtually all other aspects of the aortic valve replacement procedure remains the same. Therefore, similar long-term outcomes are to be expected.

Objectives

To conduct a meta-analysis of the only available randomised controlled trials (RCT) in the published English literature.

Data sources

Electronic search for relevant publications in MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL databases were performed. Four studies met the criteria.

Study eligibility criteria

RCT comparing minimally invasive (inverted C or L (J)-shaped) hemi-sternotomy versus conventional sternotomy for adults undergoing isolated aortic valve replacement using standard cardiopulmonary bypass technique.

Methods

Outcome measures were the length of positive pressure ventilation, blood loss, intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stay.

Results

The length of ICU stay was significantly shorter by 0.57 days in favour of the mini-sternotomy group (CI −0.95 to −0.2; p=0.003). There was no advantage in terms of duration of ventilation (CI −3.48 to 0.36; p=0.11). However, there was some evidence to suggest a reduction in blood loss and the length of stay in hospital in the mini-sternotomy group. This did not prove to be statistically significant (154.17 ml reduction (CI −324.51 to 16.17; p=0.08) and 2.03 days less (CI −4.12 to 0.05; p=0.06), respectively).

Limitations

This study includes a relatively small number of subjects (n=220) and outcome variables. The risk of bias was not assessed during this meta-analysis.

Conclusion

Mini-sternotomy for isolated aortic valve replacement significantly reduces the length of stay in the cardiac ICU. Other short-term benefits may include a reduction in blood loss or the length of hospital stay.

Article summary

Article focus

This article tests the null hypothesis that mini-sternotomy has no outcome benefit for aortic surgery.

Key message

Mini-sternotomy for aortic valve replacement reduces the length of stay in the ICU.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Use of the highest quality evidence-based medicine.

This study is not a ‘gold standard’ systematic review in the sense of searching grey literature but a confirmatory study.

A mini-sternotomy through an inverted C, L (or J)-shaped hemi-sternotomy is a technique that aims to reduce the operative trauma thereby hastening recovery and improving the cosmetic outcome of cardiac surgery. Some may be of the opinion that the latter has the potential to confer the greatest benefit. There have been numerous studies on this subject; some claim benefits in terms of postoperative outcomes, such as ventilation requirement, bleeding and intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stay for isolated aortic valve replacement performed in this way, others have been equivocal. The two larger meta-analyses in the published literature1 2 included data from a spectrum of sources ranging from randomised controlled trials (RCT) to non-randomised studies. They addressed important broad questions of safety and efficacy1 and mortality and morbidity2 associated with this method. However, they failed to show any specific advantages in terms of the length of positive pressure ventilation, blood loss, ICU and hospital stay. We believe these outcomes are best assessed by way of RCT, and thus conducted a meta-analysis to address these specific questions using only the available RCT3–6 published on this subject.

Methods

Electronic search for relevant publications in the English language were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL databases starting from 1996, when the first study of minimal invasive aortic valve replacement was conducted. The eligibility of each study was assessed by more than one author during the search of databases and references. We searched for the keywords ‘aortic valve surgery’, ‘controlled clinical trials’ and ‘minimally invasive surgery’. Reference lists of relevant articles were also searched. We only included RCT in our meta-analysis.

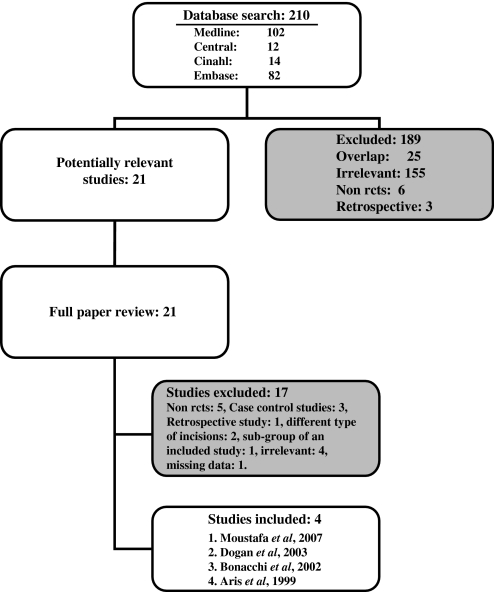

Of the 21 studies found in our search, four studies met our criteria. We selected the studies according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) the type of studies: RCT comparing minimally invasive versus conventional sternotomy; (2) participants: adult patients undergoing isolated aortic valve replacement using the standard cardiopulmonary bypass technique. The exclusion criteria were: (1) any other type of mini-sternotomy than hemi-sternotomy through the inverted C or L (J)-shaped approach; (2) the language of the article was limited to English (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Our outcome measures included the length of positive pressure ventilation, blood loss, ICU and hospital stay.

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) V.5.0. As the data obtained were continuous, combined mean differences were measured using the random effects model on the presumption that individual studies had varied outcomes. Tests for heterogeneity were performed using the χ2 test, I2 test and degrees of freedom. In this meta-analysis the risk of bias was not assessed.

Results

There were two meta-analyses on this subject,1 2 four of five RCT were subjected to our meta-analysis.3–6 One RCT was excluded due to lack of data.7 An attempt was made to contact the corresponding author for additional information with a view to include that study. This was unsuccessful. Other excluded studies8–24 were either prospective non-randomised (n=5), case–control studies (n=3), retrospective studies (n=1), different types of incision (n=2) or studies with outcome measures irrelevant to our study (n=4). The total number of patients included in this meta-analysis was the sum of the patients recruited in to the four RCT; that equals 220 patients. Table 1 illustrates each of these studies' characteristics. The following results are presented as mean differences in outcomes between mini-sternotomy and conventional sternotomy groups in the random effects method.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Study | Moustafa et al, 20073 | Dogan et al, 20034 | Bonacchi et al, 20025 | Aris et al, 19996 |

| Methods | PRCT | PRCT | PRCT | PRCT |

| No of participants | 30+30=60 | 20+20=40 | 40+40=80 | 20+20=40 |

| Mean age in years (full/mini) | 23.8/22.9 | 64.3/65.7 | 62.6/64.0 | 62.2/66.5 |

| Sex M:F (full/mini) | 15:15/16:14 | 11:9/9:11 | – | – |

| Operation | Isolated AVR | Isolated AVR | Isolated AVR | Isolated AVR |

| Interventions | Full sternotomy vs L-shaped mini-sternotomy | Complete sternotomy vs L-shaped mini-sternotomy | Standard sternotomy vs C or L-shaped mini-sternotomy | Median sternotomy vs C or L-shaped mini-sternotomy |

| Pain management with tenoxicam | Pain management with metamizol | |||

| Outcomes | Duration of ventilation | Duration of ventilation | Duration of ventilation | Duration of ventilation |

| Postop blood loss | Postop blood loss | Postop blood loss | Postop blood loss | |

| Length of ICU stay | Length of ICU stay | Length of ICU stay | Length of ICU stay | |

| Pulmonary function | Pulmonary function. | Pulmonary function | Pulmonary function | |

| Analgesic requirement | – | Analgesic requirement | – | |

| Length of hospital stay | Length of hospital stay | Length of hospital stay | Length of hospital stay | |

| Cross-clamp time | Cross-clamp time | Cross-clamp time | Cross-clamp time | |

| Bypass time | Bypass time | Bypass time | Bypass time | |

| Operation time | Operation time | Operation time | Operation time | |

| Survival to discharge | Survival to discharge | Survival to discharge | Survival to discharge |

AVR, aortic valve replacement; ICU, intensive care unit; PRCT, prospective randomised controlled trial.

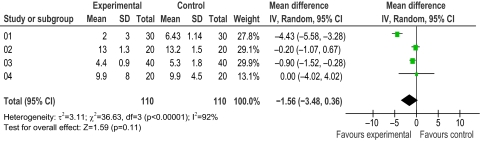

Duration of mechanical ventilation in hours

There was a statistically insignificant reduction in the duration of ventilation (figure 2). This was 1.56 h less in the mini-sternotomy group (CI −3.48 to 0.36; p=0.11).

Figure 2.

Duration of ventilation in hours.

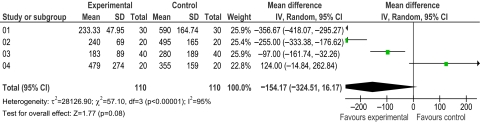

Postoperative blood loss in the first 24 h

There was a statistically insignificant reduction in blood loss of 154.17 ml in the mini-sternotomy group compared with the full sternotomy (CI −324.51 to 16.17; p=0.08), illustrated by figure 3.

Figure 3.

Postoperative bleeding in the first 24 h measured in millilitres.

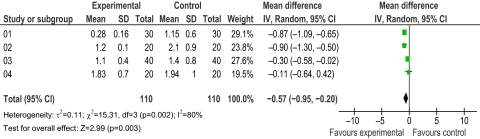

Lengths of ICU stay in days

The combined mean difference of all the studies showed that the length of ICU stay was significantly shorter by 0.57 days in favour of the mini-sternotomy group (CI −0.95 to −0.2; p=0.003). Figure 4 illustrates this primary outcome measure.

Figure 4.

Length of intensive care unit stay in days.

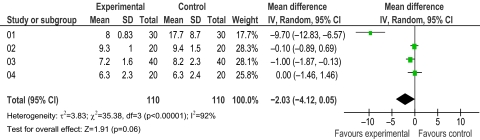

Lengths of hospital stay in days

As illustrated in figure 5, the duration of hospital stay was shorter by 2.03 days in favour of the mini-sternotomy group; however, the difference again failed to reach statistically significant levels (CI −4.12 to 0.05; p=0.06).

Figure 5.

Length of hospital stay in days.

Discussion

We performed a meta-analysis to compare the short-term postoperative outcomes in four published studies, accounted for differences in their findings, and drew a consensus view on the potential benefits of a mini-sternotomy over a full median sternotomy for a standard aortic valve replacement. The following outcome measures were assessed: duration of ventilation; postoperative blood loss; length of stay in the ICU and the hospital stay.

Using only the best available level of evidence in this meta-analysis we have clearly illustrated the advantage of the mini-sternotomy approach in reducing the number of days spent in the ICU (p=0.003) and a lack of advantage in terms of the number of hours ventilated (p=0.11). We failed to prove a clear superiority in favour of mini-sternotomy in terms of the reduction in blood loss (p=0.08) or the length of hospital stay (p=0.06). However, this shows a trend of significance. None of the previous meta-analyses showed such a trend. Our meta-analysis therefore highlights a much needed, larger and adequately powered RCT for these specific outcomes. The reduction in ICU stay by 0.57 days is a more than 50% reduction in the length of stay in ICU for a typical isolated aortic valve replacement with potential financial advantages.

This study is limited as it is not a ‘gold standard’ systematic review in the sense of searching grey literature but a confirmatory study. It only includes four RCT, with a relatively small number of subjects and outcome variables. The risk of bias was not assessed during this meta-analysis. A fifth RCT by Macheler et al was excluded due to the lack of data regarding ICU and the length of hospital stay; however, it should be noted that that trial supported our findings regarding the duration of ventilation and blood drainage per 24 h. It should also be mentioned that in the meta-analysis by Morgan et al1 three out of four of the above studies were analysed separately as a subgroup.4–6 They found a non-statistical advantage in terms of ventilation time, bleeding and ICU stay. In contrast, this meta-analysis excludes the RCT by Macheler et al but includes the most recent RCT by Moustafa et al.3 The lack of long-term data is not exclusive to this meta-analysis.

The total number of patients included in this study was 220. This is a small number considering that isolated aortic valve replacement constitutes a large proportion of our cardiac surgical work. There were two extensive well conducted meta-analyses comparing mini-sternotomy versus conventional sternotomy for aortic valve replacement.1 2 They improved the power of the study by including several comparative non-randomised studies, thus increasing the number of patients to 4586 and 4667, respectively. Those studies looked at a wide variety of non-sternotomy incisions. They excluded studies if more than 50% of reported cases were not a mini-sternotomy or operations were other than isolated aortic valve replacement. Their combined conclusion was that mini-sternotomy can be performed safely for aortic valve replacement without an increased risk of death or major complications1 but with no clinical benefits.2 In contrast, the rationale for our study was to focus on mini-sternotomy incisions and the commonest variations thereof, which included the inverted C and L or (J) mini-sternotomies. In this meta-analysis there are no non-mini-sternotomy cases and all cases underwent isolated aortic valve replacement.

There exists a degree of geographical variation that should be taken in to consideration; for example, the benefits due to the incision. Cosmesis does not appear to be a priority for patients in the western world.8 A more cosmetic scar may be more of an issue in Asia due to the younger patient population3 (table 1). This was a limitation in this study for which there were insufficient data for comparisons to be made. However, minimally invasive valve surgery is already known to improve patient satisfaction while reducing the costs of cardiac valve replacement.25 26

Conclusion

There is a significant reduction in the length of stay in the cardiac ICU and an overall benefit in short-term outcomes from mini-sternotomy for isolated aortic valve replacement. This meta-analysis would no doubt prove useful when designing a much needed, larger and adequately powered RCT on this subject.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Department of Biostatistics at the Robertson Centre, University of Glasgow, for their help with the statistical methods, the library staff at Glasgow Royal Infirmary and the audit office staff at the Golden Jubilee National Hospital for their help with the literature search.

Footnotes

To cite: Khoshbin E, Prayaga S, Kinsella J, et al. Mini-sternotomy for aortic valve replacement reduces the length of stay in the cardiac intensive care unit: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000266. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000266

Funding: The authors would like to thank Mark Woolley from Cardiosolutions for providing funding to present this work at the International Society of Minimally Invasive Cardiothoracic Surgery in Washington, DC, USA, in June 2011.

Competing interest: None.

Contributors: All authors contributed equally in the design, review of the literature, analysis and intellectual discussion of this manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version. The primary author, EK, presented this work at the International Society of Minimally Invasive Cardiothoracic Surgery in Washington, DC, USA, in June 2011.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Brown ML, McKellar SH, Sundt TM, et al. Ministernotomy versus conventional sternotomy for aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:670–9.e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murtuza B, Pepper JR, Stanbridge RD, et al. Minimal access aortic valve replacement: is it worth it? Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1121–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moustafa MA, Abdelsamad AA, Zakaria G, et al. Minimal vs median sternotomy for aortic valve replacement. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2007;15:472–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dogan S, Dzemali O, Wimmer-Greinecker G, et al. Minimally invasive versus conventional aortic valve replacement: a prospective randomized trial. J Heart Valve Dis 2003;12:76–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonacchi M, Prifti E, Giunti G, et al. Does ministernotomy improve postoperative outcome in aortic valve operation? A prospective randomized study. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;73:460–5; discussion 465–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aris A, Camara ML, Montiel J, et al. Ministernotomy versus median sternotomy for aortic valve replacement: a prospective, randomized study. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:1583–7; discussion 1587–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mächler HE, Bergmann P, Anelli-Monti M, et al. Minimally invasive versus conventional aortic valve operations: a prospective study in 120 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:1001–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrlich W, Skwara W, Klövekorn W, et al. Do patients want minimally invasive aortic valve replacement? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000;17:714–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakir I, Casselman FP, Wellens F, et al. Minimally invasive versus standard approach aortic valve replacement: a study in 506 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81:1599–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang YS, Lin PJ, Chang CH, et al. “I” ministernotomy for aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;68:40–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrne JG, Aranki SF, Couper GS, et al. Reoperative aortic valve replacement: partial upper hemisternotomy versus conventional full sternotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;118:991–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Candaele S, Herijgers P, Demeyere R, et al. Chest pain after partial upper versus complete sternotomy for aortic valve surgery. Acta Cardiol 2003;58:17–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christiansen S, Stypmann J, Tjan TD, et al. Minimally-invasive versus conventional aortic valve replacement – perioperative course and mid-term results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;16:647–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Smet JM, Rondelet B, Jansens JL, et al. Assessment based on EuroSCORE of ministernotomy for aortic valve replacement. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2004;12:53–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbi P, Rahmati M, Donal E, et al. Prospective comparison of minimally invasive and standard techniques for aortic valve replacement: initial experience in the first hundred patients. J Card Surg 2003;18:133–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Detter C, Deuse T, Boehm DH, et al. Midterm results and quality of life after minimally invasive vs conventional aortic valve replacement. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;50:337–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doll N, Borger MA, Hain J, et al. Minimal access aortic valve replacement: effects on morbidity and resource utilization. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:S1318–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farhat F, Lu Z, Lefevre M, et al. Prospective comparison between total sternotomy and ministernotomy for aortic valve replacement. J Card Surg 2003;18:396–401; discussion 402–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imazeki T, Irie Y. (Aortic valve replacement through a partial sternotomy) (In Japanese) Kyobu Geka 2006;59(Suppl 8):650–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JW, Lee SK, Choo SJ, et al. Routine minimally invasive aortic valve procedures. Cardiovasc Surg 2000;8:484–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leshnower BG, Trace CS, Boova RS. Port-access-assisted aortic valve replacement: a comparison of minimally invasive and conventional techniques. Heart Surg Forum 2006;9:E560–4; discussion E564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J, Sidiropoulos A, Konertz W. Minimally invasive aortic valve replacement (AVR) compared to standard AVR. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;16(Suppl 2):S80–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masiello P, Coscioni E, Panza A, et al. Surgical results of aortic valve replacement via partial upper sternotomy: comparison with median sternotomy. Cardiovasc Surg 2002;10:333–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mihaljevic T, Cohn LH, Unic D, et al. One thousand minimally invasive valve operations: early and late results. Ann Surg 2004;240:529–34; discussion 534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohn LH, Adams DH, Couper GS, et al. Minimally invasive cardiac valve surgery improves patient satisfaction whole reducing costs of cardiac valve replacement and repair. Ann Surg 1997;226:421–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cosgrove DM, III, Sabik JF. Minimally invasive approach for aortic valve operations. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62:596–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.