Abstract

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) in adolescents is characterized by alterations in positive emotions and reward processing. Recent investigations using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) find depression-related differences in reward anticipation. However, it is unknown whether feedback influences subsequent reward anticipation, which may highlight the context of reward processing. Ten youth with MDD and sixteen youth with no history of MDD completed an fMRI assessment using a reward task. Reward anticipation was indexed by blood oxygen level dependent signal change in the striatum following winning; losing; non-winning; and non-losing outcomes. A significant interaction between diagnostic status and outcome condition predicted reward anticipation in the caudate. Decomposition of the interaction indicated that following winning outcomes, depressed youth demonstrated reduced reward anticipation relative to healthy youth. However, no significant differences between depressed and healthy youth were found after other outcomes. Reward anticipation is altered following winning outcomes. This finding has implications for understanding the developmental pathophysiology of MDD and suggests specific contexts where altered motivational system functioning may play a role in maintaining depression.

Keywords: major depression, reward, fMRI, adolescence, striatum, context

1. Introduction

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is partially characterized by altered positive emotional functioning, including subjective, behavioral, and neural responses to reward (Davidson, 1998; Mineka et al., 1998; Lonigan et al., 1999; Lucas et al., 2000; Axelson et al., 2003; Berridge and Robinson, 2003; Gard et al., 2006; Luby et al., 2006; Whalen et al., 2008), However, specific motivational and reward-system changes relevant to the maintenance of youth depressive disorders – including motivational and consummatory aspects of reward function – have yet to be fully elucidated (Forbes and Dahl, 2005; Forbes, 2009). Reward-related brain functioning alterations are reported in adults (Pizzagalli et al., 2009) and youth with MDD (Forbes et al., 2009), noting reduced striatal activation during anticipation of reward (Forbes et al., 2009; Pizzagalli et al., 2009).

Examinations of reward-related brain functioning have primarily focused on differences between depressed and healthy participants regardless of types of feedback without testing whether alterations are contextually specific. That is, even though depression might be characterized by low motivation to obtain rewards, motivation might vary based on experience of rewards. For example, following a loss, depressed youth may be especially disappointed and less likely to anticipate success than healthy youth (Elliott et al., 1997; Elliott et al., 1998). However, Rottenberg et al. (2005) argued that the core affective deficit found in depression is inflexibility. Thus, across all contexts, people with depressive disorders have blunted responses to negative and positive events, suggesting that depressed individuals would demonstrate similar levels of reward anticipation, regardless of recent feedback.

Our previous work (Forbes et al., 2009) found reduced striatal activation to reward in youth with depressive disorders compared to healthy youth. The present study extends that work by examining striatal reactivity to reward anticipation in the context of previous winning, losing, non-winning, and non-losing outcomes. Our goal was to test whether reward motivation is altered across all or only specific contexts.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were 26 children and adolescents aged 8–16 years (M=13.31; SD=2.49; 73.1% female; 96.3% European American), with 10 meeting criteria for current MDD and 16 having no personal or family history of MDD. Recruitment information is available elsewhere (Forbes et al., 2009). The present study included fewer participants than a previous report (Forbes et al., 2009) due to requiring full imaging task data for the analyses. Consistent with the high rate of comorbidity among MDD and anxiety disorders in youth (Angold et al. 1999), 9 MDD participants had comorbid Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). Of those, 3 also had diagnoses of Social Phobia and 1 also had Panic Disorder. Participants were free of psychotropic medications, nicotine, and illicit drugs. All participants completed diagnostic assessments with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for Children (Kaufman et al., 1997) and diagnoses were confirmed by best-estimate diagnosis in consultation with a child psychiatrist. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents and from participants age 14 and older; younger participants provided verbal assent.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Reward processing

The fMRI paradigm employed reliably elicits striatal response to feedback associated with monetary reward in youth (Forbes et al., 2009). Each trial included both an anticipation period and an outcome period. Participants received win, loss, or no-change feedback for each trial. Participants were told that their performance would determine a monetary reward to be received after the scan.

Trials were presented in pseudorandom order with predetermined outcomes. During each 27-s trial, participants had 3s to guess, via button press, whether the value of a visually presented card with a possible value of 1–9 was higher or lower than 5. After a choice was made, the trial type (possible-reward or possible-loss) was presented visually for 12s (anticipation). This was followed by the “actual” numerical value of the card (500ms); outcome feedback; and a crosshair presented for 11s (outcome). There were four outcome types: win, loss, non-win, and non-loss. Trials were presented in 4 runs, with 12 trials per run and a balanced number of trial types across the task.

Participants received $1 for each win, lost 50 cents for each loss, and experienced no earnings change for non-winning and non-losing outcomes. Participants were unaware of the fixed outcome probabilities and were led to believe that performance would determine net monetary gain ($6 total earnings per participant). Participants’ engagement and motivation were maintained by verbal encouragement between runs.

2.3 Procedure

The local institutional review board approved the study. Before the scan, participants practiced the paradigm and experienced the scanning environment through the use of a simulator. Participants received $60 for the scan, plus $15 for “playing the game.” Participants were debriefed concerning the fixed outcomes for each trial after the imaging session was completed.

2.3.1 BOLD fMRI Acquisition, Processing, and Analysis

Each participant was scanned using a Siemens 3T Allegra scanner. BOLD functional images were acquired with a gradient echo EPI sequence and covered 34 axial slices (3mm thick) beginning at the cerebral vertex and encompassing the entire cerebrum and the majority of the cerebellum (TR/TE=2000/25msec, FOV=20cm, matrix=64×64). Scanning parameters were selected to optimize BOLD signal quality while sampling enough slices to acquire whole-brain data. Before the collection of fMRI data for each participant, a reference EPI scan was visually inspected for artifacts and good signal across the entire volume. The data from all participants were clear of such problems.

Whole-brain image analysis was conducted using SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). For each scan, images for each participant were realigned to the first volume in the time series to correct for head motion. The motion correction criterion for was set at <4mm or <4°, as is our practice with young people from clinical populations (E. E. Forbes et al., 2009). Realigned images were spatially normalized into Montreal Neurological Institute stereotactic space based on transformations provided by the segmented structural images, then smoothed to minimize noise and residual difference in gyral anatomy with a Gaussian filter set at 8mm full-width at half-maximum. Voxel-wise signal intensities were ratio-normalized to the whole-brain global mean. Images were adjusted for movement in six-planes during within-subject analyses.

Preprocessed data were analyzed using random effects models accounting for both scan-to-scan and participant-to-participant variability to determine task-specific regional responses. Because a priori hypotheses concerned how previous-trial outcome conditions influence reward anticipation, for each participant and scan, condition effects at each voxel were calculated using a t-statistic, producing a statistical image for reward anticipation > baseline for four conditions: (1) following a winning trial (5 total trials); (2) following a non-winning trial (4 total trials); (3) following a losing trial (6 total trials); and (4) following a non-losing trial (6 total trials). Reward anticipation trials occurred as the first trial of three runs in the task, thus, they were not included in the present analyses because of pauses between runs. Individual contrast images were used in second-level analyses to determine mean reward anticipation-related response using a full factorial model with a between subject (diagnostic group) by within (outcome condition) subject factor interaction. All tests were set to a threshold of p < 0.05, required to have a minimum extent of 10 contiguous voxels, and corrected for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate across activation clusters of interest based on region of interest (ROI) analyses. The ROI included the striatum (caudate and putamen) as defined by the WFU PickAtlas Tool (v2.4).

3. Results

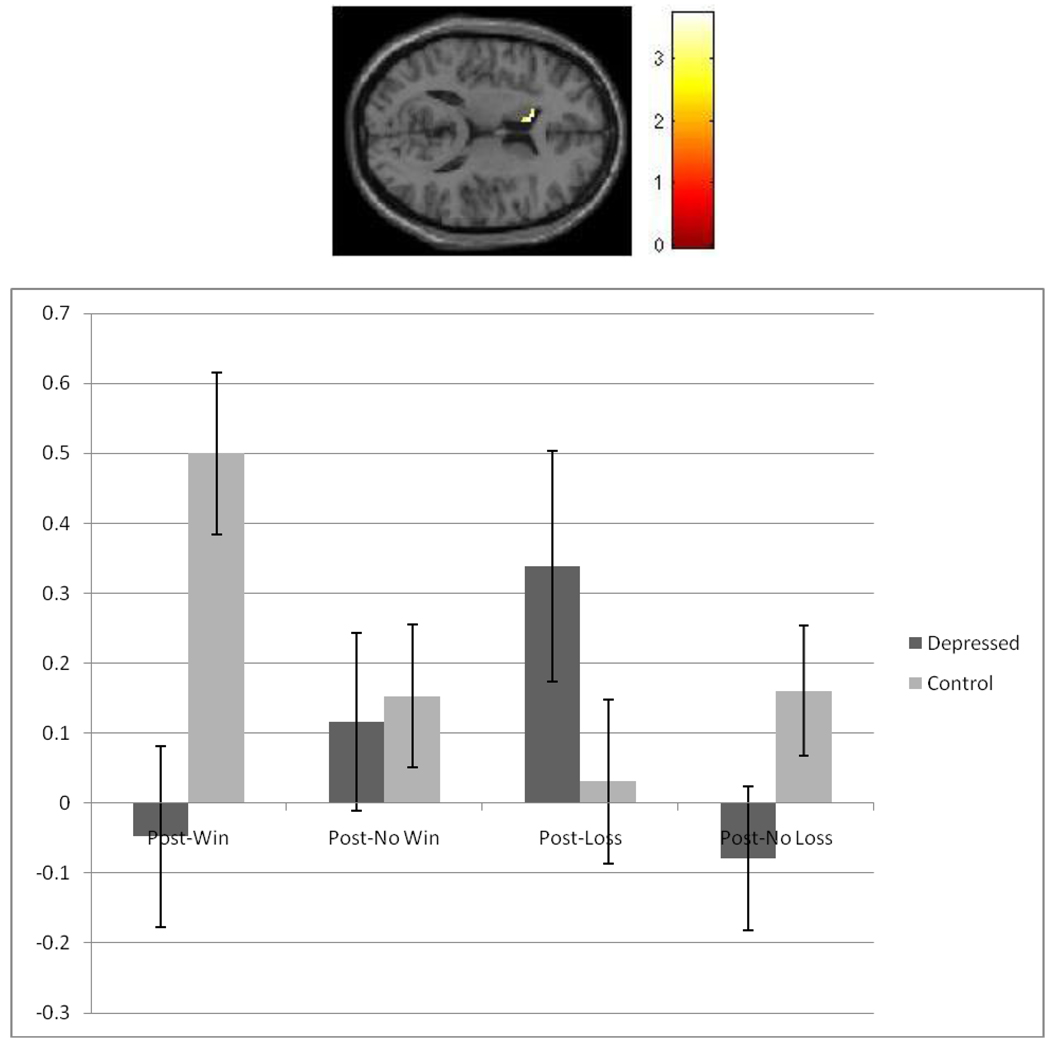

Although main effects of diagnostic status and condition were found, we focus on the significant group × condition interaction (Table 1). For simplicity, we focus on the caudate cluster with the strongest signal (Talairach coordinates: −8, 18, 12 [Figure 1, Top panel]).

Table 1.

Interaction Effects of Diagnostic Group and Condition on Reward Anticipation.

| Coordinates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kE | Region | F | z | p | |||

| x | y | z | |||||

| 22 | Caudate Body | −8 | 18 | 12 | 3.72 | 2.20 | 0.01 |

| 13 | Caudate Body | −8 | −1 | 20 | 3.70 | 2.19 | 0.01 |

| 24 | Caudate Tail | −16 | −30 | 20 | 3.61 | 2.15 | 0.02 |

| 26 | Caudate Body | 10 | −3 | 20 | 3.59 | 2.14 | 0.02 |

| 23 | Caudate Head | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3.11 | 1.89 | 0.03 |

kE = Number of voxels in the cluster. Coordinates in Talairach space (converted from MNI space using the WFU Pickatlas v.2.4).

Figure 1.

Top Panel. Image depicting left caudate cluster that differs as a function of diagnostic status and outcome condition. Cluster size = 22 voxels; [−8, 18, 12]; F (3, 96) = 3.72, p < 0.05. Bottom Panel. Plotted values are eigenvalues extracted from SPM that represent BOLD-signal change (y-axis) for reward-anticipation between depressed (dark grey) and healthy youth (light grey) following winning, non-winning, losing, and non-losing trials (error bars represent standard errors) for mean-level activation across the entire cluster.

As the focus of this work is to examine how reward anticipation differs between depressed and healthy youth based on previous outcomes, we examined post-hoc comparisons in this cluster across groups within each conditions (Figure 1, bottom panel). For reward anticipation following a winning trial, depressed youth demonstrated significantly less caudate response (t = 3.18, p < 0.001). For reward anticipation following a losing, non-winning, and non-losing trial, depressed and healthy youth did not significantly differ (ts = 1.05, 1.56, and 1.44, respectively, all ps > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Reward anticipation has been found to be reduced in depressed youth (Forbes et al., 2009). Some argue that this reflects reduced processing across all contexts (Rottenberg et al., 2005), while others suggest that biases will be present in failure or success contexts (Yuan and Kring, 2008). Building on literature examining impairments in reward anticipation (Forbes et al., 2009; Pizzagalli et al., 2009), the present study examined the interactive role of the previous trial’s outcome (i.e., winning; non-winning; losing; and non-losing) and depressive disorder on reward anticipation.

We found that reward anticipation, as indexed by striatal activation, differed between depressed and healthy youth, however, this depended upon the outcome of the previous trial. We found that depressed, relative to healthy, youth demonstrated less striatal response to reward anticipation following winning outcomes. No differences were found between depressed and healthy youth following loss, non-winning, and non-losing outcomes. Thus, depression may specifically disrupt processes of increasing reward anticipation following a winning trial. Given that reward anticipation is associated with subjective positive affect in adolescents (Forbes et al., 2009), this pattern of brain function could reflect difficulty with responding with pleasure to rewarding experiences or difficulty in allowing previous successes to influence expectations of future success. Depressed youth may benefit from interventions that enhance positive affect following successes.

The study has a number of limitations. Perhaps most relevant are the small sample and the small cluster identified for the interaction, which raises questions about the robustness of the results. As the small cluster may be a spurious finding, this result clearly requires replication. Additionally, there was a high degree of comorbidity between depressive and anxiety disorders in the sample. Thus, it is unclear how these results are specifically associated with one type of symptoms independent of the other type. The present study had a number of strengths, including relying on an established, reliable task to index striatal reactivity and investigating the research question in a well-characterized sample. In all, this study provides a foundation for understanding the larger affective context of reward motivation alterations in depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the feedback from Jorge Almeida on the data analysis. We thank the youth and families who participated in the study.

Support for this work came from NIMH P01 MH41712 to (Ryan, PI); NIMH K01 MH 074769 (Forbes, PI); NARSAD Young Investigator Award (Forbes); and NIMH T32 MH018951 (for the first author).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson DA, Bertocci MA, Lewin DS, Trubnick LS, Birmaher B, Williamson DE, Ryan ND, Dahl RE. Measuring mood and complex behavior in natural environments: Use of ecological momentary assessment in pediatric affective disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2003;13:253–266. doi: 10.1089/104454603322572589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE. Parsing reward. Trends in Neurosciences. 2003;26:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Affective style and affective disorders: Perspectives from affective neuroscience. Cognition & Emotion. 1998;12:307–330. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Sahakian BJ, Herrod JJ, Robbins TW, Paykel ES. Abnormal response to negative feedback in unipolar depression: Evidence for a diagnosis specific impairment. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1997;63:74–82. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Sahakian BJ, Michael A, Paykel ES, Dolan RJ. Abnormal neural response to feedback on planning and guessing tasks in patients with unipolar depression. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:559–571. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE. Where's the fun in that? Broadening the focus on reward function in depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:199–200. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Dahl RE. Neural systems of positive affect: Relevance to understanding child and adolescent depression? Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:827–850. doi: 10.1017/S095457940505039X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Haririz AR, Martin SL, Silk JS, Moyles DL, Fisher PM, Brown SM, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Dahl RE. Altered striatal activation predicting real-world positive affect in adolescent major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:64–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Gard MG, Kring AM, John OP. Anticipatory and consummatory components of the experience of pleasure: A scale development study. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:1086–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Hooe ES, David CF, Kistner JA. Positive and negative affectivity in children: Confirmatory factor analysis of a two-factor model and its relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:374–386. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Sullivan J, Belden A, Stalets M, Blankenship S, Spitznagel E. An observational analysis of behavior in depressed preschoolers: Further validation of early-onset depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:203–212. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000188894.54713.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE, Diener E, Grob A, Suh EM, Shao L. Cross-cultural evidence for the fundamental features of extraversion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:452–463. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Watson D, Clark LA. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:377–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Holmes AJ, Dillon DG, Goetz EL, Birk JL, Bogdan R, Dougherty DD, Iosifescu DV, Rauch SL, Fava M. Reduced caudate and nucleus accumbens response to rewards in unmedicated individuals with major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:702–710. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Gross JJ, Gotlib IH. Emotion context insensitivity in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:627–639. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen DJ, Silk JS, Semel M, Forbes EE, Ryan ND, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Dahl RE. Caffeine consumption, sleep, and affect in the natural environments of depressed youth and healthy controls. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:358–367. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsmo86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JW, Kring AM. Dysphoria and the prediction and experience of emotion. Cognition & Emotion. 2008;23:1221–1232. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.