Abstract

In this paper, we estimate the effect of school quality on the relationship between schooling and health outcomes using the substantial improvements in the quality of schools attended by black students in the segregated southern states during the mid-1900s as a source of identifying variation. Using data from the National Health Interview Survey, our results suggest that improvements in school quality, measured as the pupil-teacher ratio, average teachers’ wage, and length of the school year, amplify the beneficial effects of education on several measures of health in later life, including self-rated health, smoking, obesity, and mortality.

Keywords: Education, Health Status, School Quality

1. Introduction

The correlation between education and health is one of the most established and robust relationships in the social sciences. A notable feature of the extensive literature on this relationship is the nearly exclusive focus on the quantity of education. In this research, we build on the existing literature and study the relationship between school quality and health outcomes. School quality is a different dimension of human capital investment than quantity of schooling, and to the extent that the relationship between more education and health reflects a causal effect of human capital on health production, school quality may alter the effects of education on health. Our specific research question is: Do improvements in school quality increase the effects of educational attainment on several dimensions of health status? If the only health impact of an increase in school quality is due to an increase in educational attainment and the subsequent effect of educational attainment on health, then the effects of school quality on health are understood by the existing literature. Thus, we contribute to the literature on human capital and health production by examining how school quality could influence health and whether an additional year of schooling from higher-quality schools leads to greater health improvements than an additional year of schooling from lower-quality schools.

The empirical challenge in estimating the health effects of school quality is that the qualities of schools attended are the result of household decisions and the unobserved determinants of these decisions may be related to the later health outcomes of students. Building upon research by Card and Krueger (1992a, 1992b), we identify the effects of school quality from the dramatic reductions in the pupil-teacher ratio and increases in the length of the school year and average teachers’ wages in the schools attended by black students born between 1930 and 1950 in the 18 segregated southern states. Although the Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruled that the system of separate, racially segregated schools was unequal in 1954, southern schools remained racially segregated until the mid 1960s (Card and Krueger, 1992b; Collins and Margo, 2006; Ashenfelter, Collins, and Yoon, 2006). Thus, we focus on individuals in birth cohorts that attended segregated schools throughout their completed primary and secondary schooling.

In our analyses, we use data from the 1984–2007 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS), and link NHIS respondents to race-specific measures of school quality based on state of birth and year of birth. Our estimates of the effect of school quality suggest that, holding educational attainment constant, better school quality modestly increases the health returns to schooling for mortality, self-rated health, smoking behavior, and obesity. We also find that some (but not all) of these effects are mediated by income, occupation, and health insurance status. Our findings are the first evidence that the quality of schooling augments the increase in health from each year of schooling.

2. Background and Motivation

2.1. Conceptual Model of Health Production and Related Literature

In Grossman’s model of health capital, the efficiency of an individual’s health production function is determined by their human capital, which can affect health directly by increasing the productivity of the health inputs or indirectly by providing knowledge of how to efficiently combine inputs to produce better health (Grossman, 1972). Within this context, school quality may affect health outcomes through two primary mechanisms.

First, changes in school quality could influence the amount of human capital (including both cognitive and noncognitive skills) obtained from each year of completed schooling, which would influence the efficiency of the health production function. Taking the example of cognitive skills, experimental evidence suggests that increases in school quality, through smaller classes, increase student achievement and benefit minority students the most (Finn and Achilles, 1999; Krueger, 1999). Thus, better quality education can improve the cognitive skill returns to schooling, and cognitive abilities and knowledge have been shown to account for a substantial proportion of the relationship between years of schooling and health behaviors (Cutler and Lleras-Muney 2010).

Second, improvements in school quality could result in a higher level of educational attainment (Card and Krueger, 1996a; Sander, 1993), and a substantial body of research examines the relationship between educational attainment and health. The majority of recent research that uses rigorous econometric methods finds evidence that schooling improves health or health behaviors (Currie and Moretti, 2003; Lleras-Muney, 2005; de Walque, 2007; Grimard and Parent, 2007; Mazumder, 2007; Chou et al., 2007; Oreopoulos, 2007; Fletcher and Frisvold, 2009; among others). However, this conclusion is not universal (Clark and Royer, 2009).

In this research, we focus on the first mechanism: how school quality affects the health returns to schooling, and this focus is for several reasons. First, this mechanism is economically interesting because it adds an important dimension to the understanding of the human capital and health production relationship. If the relationship between educational attainment and health is due to the human capital content of education (as opposed to omitted variables), then better quality schooling would lead to a steeper relationship between education and health. We are able to directly test this implication. Second, understanding whether school quality affects the health returns to schooling has an important policy implication. For example, if school quality enhances the health returns to schooling, then interventions that improve school quality but do not increase educational attainment would improve health. On the other hand, if school quality increases levels of educational attainment but does not enhance the health returns to schooling, then other interventions that increase educational attainment may be more efficient at promoting health production than improvements in school quality. Third, there is likely to be less bias in estimating the effect of school quality on the slope of the education-health relationship, since omitted variables may reasonably have similar effects on the education-health relationship, regardless of the quality of the schooling (Card and Krueger, 1996a). These omitted variables are more likely to pose a problem in estimating the unconditional effect of levels of school quality on health outcomes.

Although there has been intense research interest in identifying the effects of the quantity of education on health and on identifying the effects of school quality on academic achievement and labor market outcomes, there has been very little research on the effects of school quality on health. Among the few papers examining the relationship between school quality and health, Ross and Mirowsky (1999) provide suggestive evidence that attending a more selective college is correlated with better self-rated health and functional health. Fletcher and Frisvold (2010) compare sibling outcomes and find that graduating from a higher quality college reduces the likelihood of being overweight later in life, while Fletcher and Frisvold (2011) find that attending a selective college reduces tobacco and marijuana use as a young adult.

Two recent papers follow Card and Krueger’s (1992a) identification strategy to study the impact of school quality on health-related outcomes. MacInnis (2009) examines changes in school quality throughout the U.S. for whites during the first half of the 20th century and finds that decreases in class size and increases in teacher pay and the length of the school year increase cognitive functioning in old age. Sansani (2011) also examines changes in school quality throughout the U.S. for whites. He finds that increases in school quality decrease aggregate mortality rates, imputing these rates from changes in population size across decennial Censuses.

Our research contributes to the existing literature in several ways. This paper represents the first analysis of whether an additional year of schooling from higher-quality schools leads to greater health improvements than an additional year of schooling from lower-quality schools. We use a large sample of micro data that allows us to study a diverse set of health outcomes in middle-aged and older adults and to examine the mechanisms through which school quality influences health.

Additionally, we are able to identify the effects of school quality on the slope of the education-health relationship using within state, over time changes in school quality for black schools in the South between 1936 and 1966. Although two recent papers have used a similar identification strategy to examine the influence of school quality on cognition and mortality (MacInnis, 2009; Sansani, 2011), our focus on southern-born blacks allows us to estimate the effects of school quality under weaker and more plausible assumptions because blacks were largely disenfranchised from school finance decisions during this period (Card and Krueger, 1996b; Donohue, Heckman, and Todd, 2002). To the extent that changes in school quality for whites were correlated with unobservable factors that were also correlated with health, the analyses by MacInnis and Sansani may overestimate the effects of school quality on health outcomes. Additionally, due to the public health improvements described below, we focus on cohorts born after 1929 to further reduce the possibility that changes in school quality for blacks were correlated with any unobserved determinants of health. Also, we use race-specific measures of school quality, which reduces the bias from classical measurement error and, possibly, non-classical measurement error due to the patterns of relative school quality changes for blacks and whites described in Margo (1990) and in the subsection below.1

Prior to describing our econometric strategy and data, we review the trends in schooling and school quality in the southern U.S. for cohorts from early and mid-20th century, as well as the improvements in public health during this period. Since we identify the impact of school quality on health returns to schooling using changes within states over time, the identifying assumption is that there were no corresponding changes within states over time that were correlated with the changes in school quality and were correlated with health outcomes in later life. Thus, it is important to describe what determined the changes in school quality and whether there were any improvements in public health that mirrored the changes in school quality.

2.2. Trends in School Quality for Southern-Born Blacks

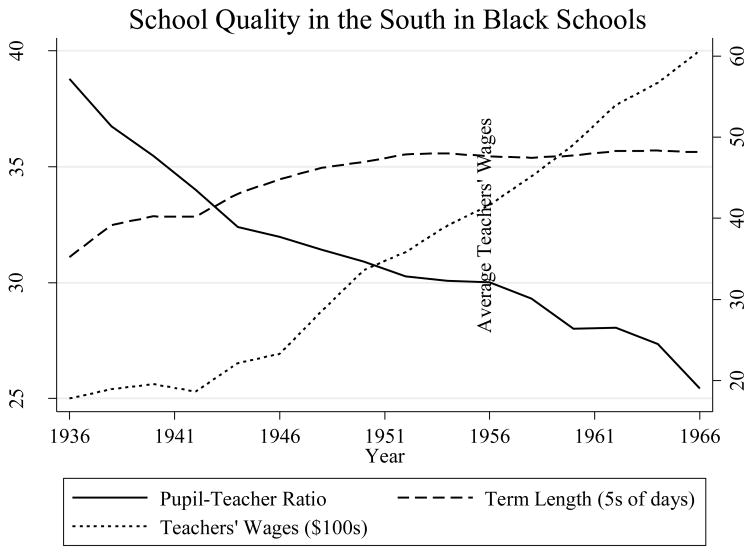

Even though schools were not fully desegregated until the mid-1960’s, beginning around 1915 there were substantial increases in the quality of schools in the South for blacks (Margo, 1990). Between 1936 and 1966, the period in which we focus our analysis, school quality substantially increased for blacks, even relative to whites. As shown in Figure 1, which is based on state averages of the quality of schools attended by black students from Card and Krueger (1992b) that are described in more detail in the next section, the average pupil-teacher ratio fell from 38.8 in 1936 to 25.4 in 1966. The average length of the school year grew from 155.5 days in 1936 to 178.1 days in 1966. Average real teacher salaries (expressed in 1967 dollars) rose from $1,777.6 in 1936 to $6,067.3 in 1966.

Figure 1.

Source: Card and Krueger (1992b).

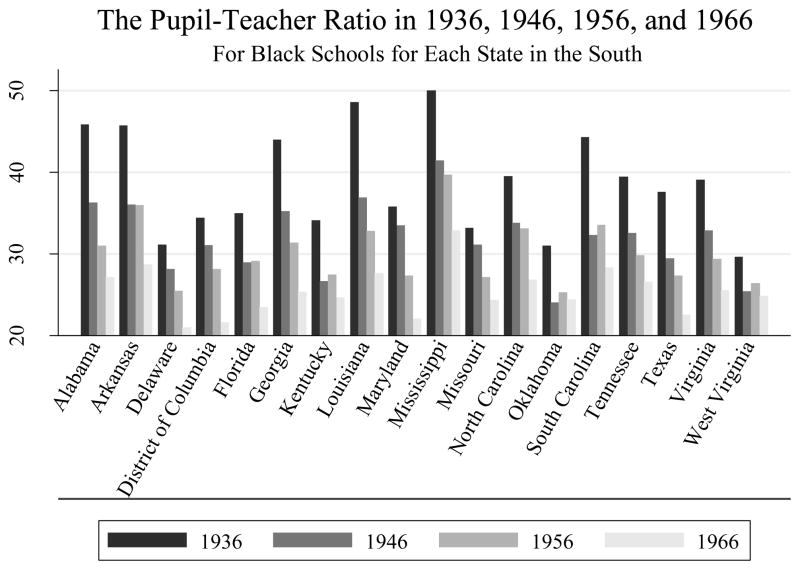

In addition to changes in school quality over time, there was substantial variation in the levels and changes in school quality within and across states (Margo, 1990; Card and Krueger, 1992a, 1992b, 1996b). As shown in Figure 2, the average pupil-teacher ratio in 1936 ranged from 30 in West Virginia to 50 in Mississippi and 6 out of 18 southern states had a pupil-teacher ratio that exceeded 40. Over time, the average pupil-teacher ratio for blacks fell in every state and by 1966 the average pupil-teacher ratio ranged from 21 to 29 among all states except Mississippi. The decrease in pupil-teacher ratio varied considerably across states, with the largest decreases occurring in Louisiana, Alabama, and Georgia, where the change in the pupil-teacher ratio was approximately three times greater than the states with the smallest decreases.

Figure 2.

Source: Card and Krueger (1992b).

The primary determinants of the variation in school quality within and across states and over time between 1936 and 1966 in the South were the legal campaign by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the demographic characteristics of the state.2 Legal action played an important role in improving school quality by compelling southern states to enforce the equality provisions of the separate-but-equal doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson and by inducing southern states to increase the quality of black schools to avoid further legal action (Donohue, Heckman, and Todd, 2002; Ashenfelter, Collins, and Yoon, 2006; Collins and Margo, 2006).3 The NAACP first targeted border states where the lawsuits were most likely to be successful and then targeted the states with the most unequal financing between black and white schools in order to generate the largest improvements in school quality for blacks (Donohue, Heckman, and Todd, 2002).

The relative size of the black population in the state at the turn of the century also influenced the changes in school quality within states over time. The states with the most unequal school financing had the highest average pupil-teacher ratios in 1936 and were also the states with the highest percentages of blacks in the population around the turn of the century.4 In states where less than 30 percent of the population was black, the average pupil-teacher ratio for black schools converged to that for white schools across the South by the late 1950s (Card and Krueger, 1992b). In states with a higher percentage of the population that was black, the average pupil-teacher ratio for black schools remained consistently higher than white schools until the desegregation of southern schools, although these states did experience a larger percentage change in school quality over time (Card and Krueger, 1992b).

The important point here is that the available evidence suggests that changes in the average school quality of the state for southern-born blacks between 1936 and 1966 were not the result of choices of local communities or families, but were largely outside of their control. Although this evidence supports our identifying assumption that omitted variables from our regressions that may affect later health were not correlated with differential trends in school quality, in the next subsection we focus on changes in public health policy during this period and further below we conduct a series of robustness checks to assess whether the results are influenced by controlling for a variety of potential factors that could affect trends in both schooling and health. Finally, we directly test whether there is a relationship between changes in school quality within states and over time and race-specific measures of health and socioeconomic conditions.

2.3. Changes in Public Health Policy

In addition to these changes in school quality, there were dramatic improvements in public health during the twentieth century.5 Particularly relevant for the South were four major diseases were largely eradicated during the first half of the twentieth century: yellow fever, pellagra, malaria, and hookworm (Humphreys, 2009). To address the possibility that our results would be confounded with the effects of public health improvements (and particularly hookworm or malaria eradication, which affected human capital outcomes (Bleakley, 2007, 2010)), we focus our sample on cohorts born in or after 1930.6 For these cohorts, the major public health improvements had already occurred, hookworm and malaria was nearly eradicated across the South, and the influence of these diseases on school attendance and educational attainment was minimal. Further, as described in the next section, we include black infant mortality rates in the regressions to control for the race-specific local health and economic conditions, including health care resources.7 Finally, as we describe in section 4.2, changes in school quality within states over time are not correlated with black infant mortality rates and, thus, it is unlikely that the estimates of the impact of school quality are biased due to unobserved changes in public health.

3. Empirical Methods

3.1. Identification Strategy

Our empirical strategy builds on that of Card and Krueger’s (1992a, 1992b) studies of the effect of school quality on earnings, and exploits the variation in school quality for black students born in southern states between 1930 and 1950. The key feature of the changes in school quality for black students is that these changes were conditionally uncorrelated with unobservable variables that may have also been correlated with health outcomes later in life. To assess whether an additional year of schooling from higher-quality schools leads to greater health improvements than an additional year of schooling from lower-quality schools, we estimate:

| (1) |

where Hisct denotes the health of individual i born in state s as part of cohort c measured at time t, Q denotes the measure of school quality, Y denotes years of schooling, Q·Y denotes the interaction between school quality and years of schooling, and G is a dummy for the sex of the individual. The vector β measures how school quality shifts the intercept of the equation, δ measures the influence of a year of schooling on health, and ρ (our coefficients of interest) measures the impact of school quality attributes on the marginal return to a year of schooling completed. φ, ξ, and υ denote state of birth, birth cohort, and survey year fixed effects, respectively, which allow us to control for time-invariant state characteristics, cohort effects, and survey year effects in a nonparametric manner. λs·t captures state-specific linear birth cohort time trends that control for unobserved state-specific factors that change linearly over time.8 α and θ represent other parameters to be estimated and η is a random error term.

The identification of the impact of school quality on the marginal health returns to schooling comes from variation in school quality experienced by black students within states and over time. To address the possibility that changes in school quality could have been correlated with changes in contemporary conditions that may have affected health, our models also include the state-specific, cohort-specific measure of black infant mortality rates (IMR) as a measure of contemporaneous health conditions for blacks. IMR is the best available measure of these conditions and is a useful covariate for several reasons. First, IMR has been shown to be sensitive to changes in local health care resources (Almond, Chay, and Greenstone, 2008) and environmental conditions (Chay and Greenstone, 2003), implying that if there were changes in health care resources or environmental conditions for blacks that were correlated with changes in school quality and might affect health later in life, we would expect it to be reflected in IMR. Second, IMR is also responsive to social and economic conditions (Fishback, Haines, and Kantor, 2001), implying that if there were changes in social or economic conditions for blacks that may have been correlated with changes in school quality, we would also expect that to be reflected in IMR. Third, race-specific IMR data are available for all states and cohorts in our sample. Although our preferred specifications include IMR, our results are not substantively altered by its exclusion, which lends support to the assumption that the changes in school quality for blacks during this period were exogenous with respect to later health outcomes.

3.2. Data

The data for our analyses come from the National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS). The NHIS is a nationally-representative survey of the non-institutionalized U.S. population that is conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics and interviews between approximately 60,000 and 120,000 individuals per year. The NHIS is the best available dataset for our analyses for several reasons. First, it contains extensive survey questions about a number of domains related to health status. Second, it has a relatively large sample size, which is helpful when restricting to comparisons among blacks born in specific cohorts and specific regions of the U.S. Third, the restricted-use NHIS file contains year of birth and state of birth, which allows us to link individuals to the state-race-cohort measures of average school quality and infant mortality rates.9 We use data from the 1984–2007 NHIS, which are the years that the NHIS collected data on state of birth.10 We limit our analyses to black respondents who were born between 1930 and 1950 in one of 18 southern states.11 This leaves us with a sample of 42,902 individuals, although sample sizes for some analyses are smaller due to missing data.

Our analyses focus on several dependent variables that reflect different dimensions of health. We chose the dependent variables based on their conceptual and policy relevance, along with preferring variables that were collected in most (if not all) years of the NHIS and were comparable across survey years. Our first outcome domain is general health status, which is measured using the common five-level self-rated health question (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor). Self-rated health is set equal to 1 if the individual reports their health as excellent and equal to 5 if the individual reports their health as poor, so that an increase in the variable is a decrease in self-reported health. The second outcome domain is disability, which is measured using a binary variable for whether or not the respondent reports that he or she cannot perform their major activities or is limited in the amount/kind of their major activities due to chronic health conditions. The third outcome domain is health behavior and we focus on smoking and obesity. Our measures of smoking are a binary variable for whether the respondent reports having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime and a binary variable for whether the respondent reports being a current smoker.12 Obesity is defined as a binary variable for whether respondents have a BMI greater than 30. Our final outcome is mortality, and specifically, time until death (in months). The mortality data are based on the records of the National Death Index, and were obtained through a restricted data use agreement with the NCHS. The mortality data are only available for the survey years of 1986–2004, and the data follow mortality status only through the end of 2006.

The sample means and sample sizes for the dependent variables are found in Table 1, panel A. Thirty-six percent of the sample reports their health as excellent or very good and 30 percent reports their health as fair or poor. Approximately 28 percent of the sample reports a disability. Thirty percent of the sample is obese and 31 percent currently smoke. Seventeen percent of the sample died by 2006.

Table 1.

Sample Summary Statistics

| Mean | Standard Deviation | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Dependent Variables | |||

| Self-Rated Health (1=excellent, 5=poor) | 2.88 | 1.176 | 42720 |

| Excellent/Very Good Health | 0.362 | 42720 | |

| Fair/Poor Health | 0.300 | 42720 | |

| Any Disability | 0.284 | 42877 | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 28.128 | 5.686 | 34532 |

| Obese (BMI>30) | 0.303 | 34532 | |

| Morbidly Obese (BMI>35) | 0.108 | 34532 | |

| Current Smoker | 0.314 | 16434 | |

| Died by December 2006 | 0.174 | 36660 | |

| B. Key Independent Variables | |||

| Pupil-Teacher Ratio | 32.513 | 4.332 | 42902 |

| Teacher Wages (in real 1967 $1000’s) | 3.231 | 1.434 | 42902 |

| Term Length (in 10 day units) | 17.197 | 1.134 | 42902 |

| Years of Completed Education | 12.101 | 3.342 | 42662 |

| P-T Ratio × Education† | −2.791 | 14.949 | 42662 |

| Teacher Wages × Education† | 1.046 | 4.824 | 42662 |

| Term Length × Education† | 0.592 | 4.199 | 42662 |

| C. Covariates | |||

| Female | 0.580 | 42902 | |

| Birth Year | 1941.012 | 6.062 | 42902 |

| Survey Year | 1994.151 | 6.289 | 42902 |

| Infant Mortality Rate (deaths/1000 births) | 56.767 | 15.950 | 42902 |

Notes: The sample is composed of blacks born between 1930 and 1950 in one of the 18 southern states who were interviewed in the NHIS between 1984 and 2007. The school quality variables are measures of the quality of schools in the South attended by black students. The infant mortality rate is also race-specific; it measures the number of deaths among black infants less than 12 months of age divided by the number of live births (in 1000s) of black infants.

Sources: National Health Interview Survey 1984–2007, Card and Krueger (1992b), Statistical Abstract of the United States, Vital Statistics of the United States.

Interaction terms are computed by multiplying the mean-centered interacted variables.

Our key independent variables are three measures of educational quality: the state-, race-, and cohort-specific average pupil-teacher ratio, average annual teacher pay (expressed in real 1967 $1000’s), and average length of school term (expressed in 10-day units) for grades K-12 in public schools.13 These measures are used in Card and Krueger (1992b) and are derived from data in the Biennial Surveys of Education, state education reports, and annual reports from the Southern Education Reporting Service.14, 15 Due to the segregated nature of schools in the South between 1936 and 1966, these school quality measures are available separately for black and white schools. To construct the measures of educational quality, we follow Card and Krueger (1992b) and use data from the 1970 census to derive the average of the quality measures based on the years that each individual in each race-state-cohort attended school, which is determined based on the number of years of schooling attended, state-of-birth, and the year in which the individual was 6 years old. These values for individuals are then averaged to determine the school quality for each cohort within each state.16 The summary statistics for these variables are found in Table 1, panel B. On average, the schools attended by this sample had 32.5 students per teacher, teachers were paid $3231 annually in 1967 dollars, and students attended school for 170 days per year. Individuals completed 12 years of schooling, on average.

We also include state-, cohort-, and race-specific IMR data in our analyses, which are available in various years of the Statistical Abstracts of the United States and Vital Statistics of the United States. For cases where there were missing IMR data and it was possible to interpolate, we did so using linear interpolation. In our analyses, we consider the state-, cohort-, and race-specific IMR when each cohort was six years old as a proxy for the stock of health resources that were available when cohorts were entering school, with the understanding that there are numerous inputs to health stock, including access and quality of health care, along with social, economic, and environmental inputs.17 The summary statistics for IMR, along with the other covariates, are found in Table 1, panel C. Demographic characteristics from the NHIS data demonstrate that 58 percent of the sample is female and the average age is 52.7 years.

We estimate our models of self-rated health using OLS.18 For the dependent variables that are binary (smoking, obesity, and disability), we estimate linear probability models to facilitate interpretation of the coefficients on the key interaction terms.19 For the dependent variable that is time until mortality, with censoring at December 2006, we estimate Cox proportional hazards models. All of our regression models are estimated with heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors that are clustered on the state of birth.

4. Results

4.1. Main Results

We report the results from models where the three school quality measures are entered separately.20 In Tables 2 through 6, we report the results of the impact of school quality on each health outcome separately.21 Each table is formatted similarly. The results from the specifications from equation (1) are shown in the odd-numbered columns; the results for the pupil-teacher ratio are in column (1), the results for teachers’ wages are in column (3), and the results for term length are in column (5).

Table 2.

OLS Models of Self-Rated Health (1=Excellent, 5=Poor)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | −0.0953*** (0.00205) | −0.0957*** (0.00132) | −0.0953*** (0.00241) | −0.0957*** (0.00136) | −0.0946*** (0.00241) | −0.0956*** (0.00135) |

| P-T Ratio* Educ | 0.00188*** (0.000549) | 0.00193* (0.000958) | ||||

| Teacher Wages* Educ | −0.00536*** (0.00138) | −0.00298 (0.00568) | ||||

| Term Length* Educ | −0.00538*** (0.00147) | −0.00434 (0.00317) | ||||

| P-T Ratio | −0.00596 (0.0145) | −0.0161 (0.0143) | ||||

| Teacher Wages ($1000s) | 0.0686 (0.0537) | 0.0446 (0.0590) | ||||

| Term Length (10 days) | −0.0216 (0.0339) | −0.000754 (0.0228) | ||||

| State Time Trends | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Full Specification | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Observations | 42486 | 41939 | 42486 | 41939 | 42486 | 41939 |

| R-squared | 0.108 | 0.108 | 0.108 | 0.108 | 0.108 | 0.108 |

Notes: Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors that allow for clustering within state of birth are in parentheses. The P-T Ratio refers to the pupil-teacher ratio. Additional covariates that are not shown include sex, the state infant mortality rate for blacks at age 6, state of birth fixed effects, year of birth fixed effects, and survey year fixed effects. Covariates that are included in the full specification include the state infant mortality rate for blacks at birth, interaction terms between birth year and years of schooling, the interaction of the infant mortality rate (at birth and at age 6) and years of schooling, and the following state variables as well as the interaction terms between these variables and years of schooling: per capita income, state average manufacturing wages, average value of an acre of farm land, state population, years of compulsory school attendance, years of schooling required to obtain a work permit, and the average family size for blacks in the state, the average Duncan SEI occupational income score for blacks in the state, the average Duncan SEI occupational earnings score for blacks in the state, the average Duncan SEI occupational education score for blacks in the state, and the percent in the labor force of blacks in the state.

Sources: See Table 1.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Table 6.

Cox Proportional Hazards Models of Mortality

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | −0.0636*** (0.00447) | −0.0700*** (0.00370) | −0.0668*** (0.00449) | −0.0702*** (0.00356) | −0.0604*** (0.00488) | −0.0699*** (0.00373) |

| P-T Ratio* Educ | 0.00269*** (0.00102) | 0.00353*** (0.00114) | ||||

| Teacher Wages* Educ | −0.0113*** (0.00235) | −0.0147 (0.00979) | ||||

| Term Length* Educ | −0.00452 (0.00315) | 0.00112 (0.00423) | ||||

| P-T Ratio | 0.0310 (0.0221) | 0.0141 (0.0245) | ||||

| Teacher Wages ($1000s) | 0.0582 (0.0587) | 0.133 (0.104) | ||||

| Term Length (10 days) | 0.00821 (0.0533) | 0.0617 (0.0562) | ||||

| State Time Trends | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Full Specification | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Observations | 36476 | 35995 | 36476 | 35995 | 36476 | 35995 |

The results from the models of general health status, as shown in Table 2 indicate that school quality significantly increases the beneficial effect of education on self-rated health. A decrease in the pupil-teacher ratio, which is an increase in school quality, increases the effect of education on self-rated health. A one-standard deviation improvement in school quality amplifies the marginal effect of education on self-rated health by −0.008 (relative to a sample mean marginal effect of education of −0.095).22 Improvements in term length and teacher wages also significantly increase the relationship between education and self-rated health. A one-standard deviation improvement in teacher wages and term length increases the magnitude of the marginal effect of education on self-rated health by 0.008 and 0.006, respectively (both increases are relative to a sample mean marginal effect of education of −0.095) All of the key interaction term coefficients are significantly different from zero at the one percent level of significance. We also find that school quality increases the marginal effect of education on reporting excellent or very good self-rated health, but that the relationship for fair or poor self-rated health is weaker and not statistically significant (results not shown).

As shown in Table 3, improvements in school quality also increase the return to years of schooling on the probability of reporting a disability. However, these coefficients are very small relative to the education coefficients, and none of the coefficients are statistically significant.

Table 3.

Linear Probability Models of Any Disability

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | −0.0289*** (0.00103) | −0.0290*** (0.000500) | −0.0288*** (0.00100) | −0.0291*** (0.000421) | −0.0287*** (0.000986) | −0.0290*** (0.000511) |

| P-T Ratio* Educ | 0.000253 (0.000207) | 0.000345 (0.000374) | ||||

| Teacher Wages* Educ | −0.000426 (0.000595) | −0.00250 (0.00213) | ||||

| Term Length* Educ | −0.000216 (0.000538) | 0.000801 (0.000946) | ||||

| P-T Ratio | −0.00524 (0.00557) | −0.000296 (0.00457) | ||||

| Teacher Wages ($1000s) | 0.00576 (0.0209) | 0.00330 (0.0298) | ||||

| Term Length (10 days) | 0.0311*** (0.0106) | 0.0366*** (0.00821) | ||||

| State Time Trends | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Full Specification | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Observations | 42640 | 42202 | 42640 | 42202 | 42640 | 42202 |

| R-squared | 0.076 | 0.077 | 0.076 | 0.077 | 0.076 | 0.077 |

We find that improvements in school quality significantly amplify the effect of years of schooling on the probability of being obese (Table 4). Our estimates imply that a one standard deviation decrease in pupil-teacher ratio amplifies the magnitude of the marginal effect of schooling on obesity by 0.0015, and a one standard deviation increase in term length of 11.3 days amplifies the magnitude of the marginal effect of schooling on the probability of being obese by 0.0013 percentage points (relative to a sample average marginal effect of −0.013).23 We find similar and statistically significant patterns for BMI and morbid obesity, and similar but less precisely estimated results for overweight (not shown).24

Table 4.

Linear Probability Models of Obesity

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | −0.0128*** (0.00106) | −0.0129*** (0.000494) | −0.0129*** (0.000993) | −0.0130*** (0.000435) | −0.0127*** (0.000931) | −0.0129*** (0.000516) |

| P-T Ratio* Educ | 0.000352** (0.000137) | 0.000310 (0.000335) | ||||

| Teacher Wages* Educ | −0.00119** (0.000433) | −0.00255 (0.00185) | ||||

| Term Length* Educ | −0.00118** (0.000409) | −0.000180 (0.000837) | ||||

| P-T Ratio | 0.00546 (0.00440) | −0.000490 (0.00551) | ||||

| Teacher Wages ($1000s) | −0.0180 (0.0193) | −0.0405** (0.0187) | ||||

| Term Length (10 days) | −0.0203 (0.0140) | −0.00885 (0.0127) | ||||

| State Time Trends | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Full Specification | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Observations | 34490 | 34082 | 34490 | 34082 | 34490 | 34082 |

| R-squared | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 |

School quality alters the effect of schooling on smoking behavior. Improvements in both pupil-teacher ratio and teacher wages significantly amplify the marginal effect of schooling on the probability of being a current smoker (Table 5, columns 1 and 3). The coefficient for term length is in the expected direction but is not statistically significant. We find that a one standard deviation improvement in the pupil-teacher ratio increases the magnitude of the marginal effect of schooling on the probability of smoking by 0.004 percentage points, relative to a sample mean marginal effect of education of −0.015. We find similar patterns for models of whether the respondent reported having ever been a smoker (not shown). Those results are all statistically significant, but are smaller in magnitude than the estimates for the probability of currently smoking, suggesting that increases in school quality matter both for the margin of starting smoking and the margin of quitting smoking.

Table 5.

Linear Probability Models of Currently Smoking

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | −0.0147*** (0.00136) | −0.0152*** (0.000893) | −0.0149*** (0.00133) | −0.0153*** (0.000855) | −0.0142*** (0.00153) | −0.0152*** (0.000844) |

| P-T Ratio* Educ | 0.000886** (0.000407) | 0.000518 (0.000671) | ||||

| Teacher Wages* Educ | −0.00321*** (0.000779) | −0.00107 (0.00292) | ||||

| Term Length* Educ | −0.00202 (0.00127) | 0.0000361 (0.00129) | ||||

| P-T Ratio | −0.0107 (0.00866) | −0.0125 (0.00981) | ||||

| Teacher Wages ($1000s) | 0.0120 (0.0203) | 0.00907 (0.0205) | ||||

| Term Length (10 days) | −0.00974 (0.0181) | −0.0221 (0.0185) | ||||

| State Time Trends | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Full Specification | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Observations | 16388 | 16186 | 16388 | 16220 | 16388 | 16186 |

| R-squared | 0.065 | 0.068 | 0.066 | 0.068 | 0.065 | 0.068 |

The results for our proportional hazards models of mortality are found in Table 6. Consistent with most of the findings that we have reported in this section, we find that increases in school quality increase the marginal effect of schooling on the probability of mortality. The key coefficients for pupil-teacher ratio and term length (Table 6, columns 1 and 3), are both significant at the one percent level of significance. The coefficient for term length is also in the expected direction, but is not statistically significant.

Although the parameter of interest for our study is the coefficient on the interaction between school quality and years of schooling, we also note the estimated coefficients on the school quality variables. A priori, we did not have a clear prediction for the sign of these coefficients. A negative coefficient is in fact possible if the individuals who attain more schooling in response to better school quality are relatively better producers of health, thus lowering the average health of the lowest education individuals (Card and Krueger (1996c) describe this effect in the context of earnings). Overall, we do not find a consistent relationship between the main school quality variables and health outcomes. We find no statistically significant relationship for most of the outcomes and school quality variables, with the exception of a significant negative coefficient for term length in the model of any limitations and positive, statistically significant coefficients for the relationship between teachers’ wages and obesity.

As opposed to the reduced-form impact of school quality, our specifications emphasize the interaction between school quality and completed schooling. Estimates of the impact of school quality on the rate of return to education on health outcomes are less likely to be influenced by any potentially omitted variables than the reduced form impact of school quality on health outcomes since omitted variables, such as family background characteristics, are likely to cause a similar bias in the education-health relationship regardless of the level of school quality (Card and Krueger, 1996b). Thus, the omitted variables likely would have a stronger influence on the estimate of the impact of school quality on levels of health than the slope of the relationship between education and health. Nevertheless, we present the results of analogous reduced form models of levels of health outcomes as a function of levels of school quality in the online appendix. These results suggest that there is little overall relationship between school quality and health outcomes.25

4.2. Robustness Checks

We test the robustness of our main results by relaxing our assumptions in several ways. First, we allow the health returns to schooling to vary by birth year. Second, in addition to the race-state-cohort specific measure of IMR, we include a number of time-varying state-cohort specific variables in our models that may be correlated with local demand for school quality and subsequent health outcomes. These variables include race-specific measures of average family size, average Duncan SEI occupational income score, average Duncan SEI occupational earnings score, average Duncan SEI occupational education score, and the percent in the labor force, all of which are derived from decennial census data (Ruggles et al., 2010).26 We also include non-race specific measures of per capita income, state average manufacturing wages, average value of an acre of farm land, state population, years of compulsory school attendance, and years of schooling required to obtain a work permit. Third, we also include interactions of those variables with years of schooling, along with the interaction between race-specific infant mortality rates and years of schooling. Finally, we also add IMR measured at birth to address the possibility that local health conditions at the time of birth is more relevant for later health outcomes. The results of these models are found in the even-numbered columns of Tables 2–6.

For the most part, the results of these models are comparable to the main results. We focus our discussion here on the main results that were statistically significant. For self-rated health, the point estimates are similar, but are estimated with less precision (and the key coefficients for teacher wages and term length are no longer statistically significant). For the weight-related outcomes, most of the key coefficients are larger than in the main models, but overall they are estimated with less precision. The results for smoking behavior, however, are sensitive to the inclusion of these additional variables, and the point estimates are much smaller and not statistically significant. For the models of mortality, the point estimates for both the key pupil-teacher ratio and teacher wage coefficients are similar to the main results but they are estimated with less precision and the key teacher wage coefficient is no longer statistically significant.

A potential critique of our identification strategy is the possibility of selective migration. Families who place an emphasis on education and invest in the welfare of the children may move from a state with low quality schools to a state with high quality schools; in this case, it may be the parental investments and not the quality of schools that influence health. Assigning school quality measures to individuals based on state of birth as opposed to state of schooling helps to alleviate this concern, as does including measures of state-level variables in our full models that reflect families’ demands for human capital investments. Card and Krueger (1992a) find that adjusting for the interstate mobility of school-aged children leads to a slight increase in the magnitude of their estimates, which suggests that estimates that do not correct for mobility are likely to be slightly biased towards zero. In addition, although many blacks migrated to the North during the mid-1900s, mobility during childhood was relatively uncommon. Using Census data, we find that 90 percent of southern-born black youths younger than 18 years old who were born between 1930 and 1950 still resided in their state of birth,27 and that the probability of moving out of one’s state of birth before age 18 was uncorrelated with school quality in the state of birth (results not shown).

The second concern related to migration is whether better school quality influences migration and whether individuals choose to move to regions that provide a healthier environment or greater access to health care; in this case, it may be the health returns to migration, not the quality of schools that influence health (e.g., Heckman, Layne-Farrar, and Todd, 1996). However, this critique may apply to the relationship between school quality and earnings more so than the relationship between school quality and health. For instance, Logan (2008) finds that the stock of health was not a strong determinant of black migration from the South to the North prior to 1910. Additionally, recent research finds that adjusting Card and Krueger’s (1992a) results for selective migration does not alter their conclusions (McHenry 2010). To examine the possibility of selective migration in our context, we examine the robustness of the results to the inclusion of dummy variables for the current Census region, along with current Census region interacted with years of schooling so that the identification is based off of people who moved (not shown). Including these variables did not influence the results. Further, to the extent that increases in school quality alter the marginal returns to migration, it is unclear that it is even appropriate to adjust for selective migration (Card and Krueger 1996c).

Another potential limitation of our analysis is the possibility of selective mortality, where blacks with a lower quality education die early. However, if school quality decreases mortality, then selective mortality should bias our results towards zero. Further, it is important to emphasize that the average age of our sample is 52.7 years and the youngest age is 35 years, which should mitigate the potential for any bias due to selective mortality. We also test for the possibility of attrition bias by estimating regression models of state- and birth-cohort rates of survival until 1980 on the measures of school quality and state and birth year fixed effects.28 The results of these models (not shown) are not significant and suggest that selective attrition is unlikely to be a major bias in our estimates.

Finally, we test the assumption in our analyses that changes in school quality were uncorrelated with changes in the stock of local factors that also could affect health. We do this by estimating state-level models of race-specific IMR as a function of contemporaneous school quality, along with state and year fixed effects and state-specific time trends. The results of these models (not shown) indicate no correlation between changes in race-specific school quality and changes in race-specific infant mortality.29

4.3 Mechanisms

The effects of attending higher quality schools on the health returns to schooling could work through a variety of channels. First, to the extent that school quality increases earnings, individuals who experience better school quality can maximize health production subject to more generous resource constraints. Second, human capital may influence occupational choice, which is related to environmental exposures, earnings, and health insurance coverage. Third, school quality may influence peer networks, which could further increase the influence of human capital on health outcomes (Aizer and Stroud, 2010; Lleras-Muney and Jensen, 2010).

In this section we investigate four potential mediators – occupation, income, health insurance, and marital status – of the school quality-health relationship to investigate the specific mechanisms through which school quality increases the health returns to schooling. First, occupation is coded as 15 categories based on the 1995 revision of the Standard Occupational Classification, including not in the labor force as an occupation category. Second, family income is imputed from the NHIS income categorizations by taking the mean family income from the Current Population Survey (CPS) for each NHIS income category from the appropriate CPS year. Third, health insurance status is coded as four categories: privately insured, Medicare, other public coverage, or uninsured.30 Fourth, marital status is coded as four categories: married, divorced/separated, widowed, or never married. To test whether these variables account for the effect of school quality on health returns to schooling, we add each of these variables to our baseline models sequentially, and then we include all four mediators simultaneously. This exercise has a few important limitations. First, these measures are all potentially endogenous, and may reflect the effects of health or may be correlated with other unobserved variables.31 Second, these measures are imperfect proxies – it would be preferable to have a measure of a person’s longest occupation which is unknown for many of the people in our sample who are retired and out of the labor force, or to have a better measure of permanent income. Hence, we consider these analyses to be only suggestive of the potential mediators of the relationship between school quality and health.

We focus these analyses on self-rated health, obesity, and mortality since these were the outcomes with the effects of school quality that were most robust to the extended specification described in the previous section. The results of these models are in Tables 7 through 9, where column 1 reproduces the key interaction coefficient from the main models, columns 2 through 5 show the key coefficients after including the mediators sequentially, and column 6 shows the key coefficient after including all of the potential mediators.

Table 7.

Self-Rated Health – Potential Mediators

| (1) Base model | (2) Occupation | (3) Income | (4) Insurance | (5) Marital status | (6) All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Pupil-Teacher Ratio | ||||||

| P-T Ratio* Education | 0.00188*** (0.000549) | 0.00134*** (0.000452) | 0.000834* (0.000472) | 0.00122** (0.000476) | 0.00184*** (0.000542) | 0.000396 (0.000452) |

| Observations | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 |

| R-squared | 0.108 | 0.171 | 0.138 | 0.151 | 0.112 | 0.207 |

| Panel B. Teacher Wages | ||||||

| Wages* Education | −0.00536*** (0.00138) | −0.00343** (0.00136) | −0.00126 (0.00131) | −0.00233 (0.00137) | −0.00521*** (0.00135) | 0.000608 (0.00145) |

| Observations | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 |

| R-squared | 0.108 | 0.171 | 0.138 | 0.151 | 0.112 | 0.207 |

| Panel C. Term Length | ||||||

| Length* Education | −0.00538*** (0.00147) | −0.00379*** (0.00115) | −0.00196* (0.000971) | −0.00301*** (0.000952) | −0.00520*** (0.00146) | −0.000561 (0.000859) |

| Observations | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 | 42486 |

| R-squared | 0.108 | 0.171 | 0.138 | 0.151 | 0.112 | 0.207 |

Notes: Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors that allow for clustering within state of birth are in parentheses. The P-T Ratio refers to the pupil-teacher ratio. Additional covariates that are not shown include sex, the state infant mortality rate for blacks, state of birth fixed effects, year of birth fixed effects, survey year fixed effects, and state-specific linear time trends. Column (2) includes 14 occupation dummy variables as additional covariates. Column (3) includes family income as an additional covariate. Column (4) includes 3 health insurance categorical variables as additional covariates. Column (5) includes 3 marital status categorical variables as additional covariates. Column (6) includes all of the above variables as additional covariates.

Sources: See Table 1.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Table 9.

Cox Proportional Hazard Models of Mortality – Potential Mediators

| (1) Base model | (2) Occupation | (3) Income | (4) Insurance | (5) Marital status | (6) All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Pupil-Teacher Ratio | ||||||

| P-T Ratio* Education | 0.00269*** (0.00102) | 0.00183** (0.000859) | 0.00164* (0.000867) | 0.00212** (0.000921) | 0.00242** (0.000959) | 0.00112 (0.000746) |

| Observations | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 |

| Panel B. Teacher Wages | ||||||

| Wages* Education | −0.0113*** (0.00235) | −0.00742*** (0.00220) | −0.00714*** (0.00221) | −0.00856*** (0.00239) | −0.0103*** (0.00224) | −0.00421* (0.00219) |

| Observations | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 |

| Panel C. Term Length | ||||||

| Length* Education | −0.00452 (0.00315) | −0.00229 (0.00263) | −0.00164 (0.00245) | −0.00291 (0.00269) | −0.00399 (0.00301) | −0.000149 (0.00211) |

| Observations | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 | 36476 |

For self-rated health, we find that much of the observed relationship is explained by income. Occupation and health insurance attenuate the relationship, but only somewhat. Marital status does not explain any of the relationship between school quality and self-rated health. When all of the mediators are included simultaneously, the school quality interaction coefficients are no longer significantly different from zero.

We find a somewhat different pattern when examining the relationship between school quality and obesity. Occupation appears to explain some of the relationship, while income, insurance status, and marital status do not. After including all the mediators simultaneously, the key coefficients are between one-quarter to one-third smaller than the main results, but still statistically significant.

Finally, occupation and income partially explain the effect of school quality for mortality. Health insurance appears to be a less important mediator than occupation and income, and marital status does not mediate the relationship. When all mediators are included simultaneously, the key coefficients on the two school quality measures that were significant in the main models (pupil-teacher ratio and teacher wages) are much smaller, but the coefficient on the teacher wage interaction remains significant at the 10 percent level of significance.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

In this research, we ask a question that has important economic and policy relevance, but has received scant attention in the research literature: does school quality affect the health returns to schooling? Relying on the significant improvements within states over time in school quality, our results suggest that school quality increases the effects of years of schooling on health outcomes later in life. Nevertheless, it is important to note these effects are somewhat modest in magnitude. Consider the improvements in the sample average pupil-teacher ratio between 1930 and 1950, which is approximately a 10 unit decrease. Our estimates suggest that at the sample mean of the pupil-teacher ratio, an additional four years of schooling improves self-rated health by 0.38 points.32 If pupil-teacher ratios were lowered by the magnitude of the pupil-teacher ratio improvement between the 1930 and 1950 cohorts, an additional four years of schooling would improve self-rated health by 0.46 points.33 Similarly, an additional four years of schooling at the sample mean of the pupil-teacher ratio would reduce the probability of being obese by 0.051, while it would reduce the probability of being obese by 0.065 if the pupil-teacher ratio were reduced by 10. An additional four years of schooling under the sample mean pupil-teacher ratio would reduce the probability of currently smoking by 0.059, while it would reduce the probability of currently smoking by 0.093 if there were on average 10 fewer pupils per teacher.

Our findings are congruent with the recent research by Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2010), who find that a substantial proportion of the education and health relationship is explained by the effect of schooling on cognitive abilities, and that what is learned in primary and secondary school is important for predicting later health behaviors. As noted in section 2.2 of our paper, there is evidence linking school quality to cognitive abilities. Although we are unable to directly test whether cognitive abilities mediate the relationship between school quality and health, the fact that we are unable to fully explain the effects with the mediators that we investigate suggests that cognitive abilities may play a role in this relationship. To the extent that they affect individuals’ decisions about investments in future health capital, non-cognitive skills may also play a role in this relationship, though there is no empirical evidence on the role of school quality on non-cognitive skills (Becker and Mulligan 1997).

As emphasized, we focus our analysis on southern-born blacks who were born between 1930 and 1950 to improve the strength of the causal inference in our empirical analyses. A consequence of this choice is that to a certain extent, we improve internal validity at the expense of external validity. However, it is important to note that for the birth cohorts that we study, 74 percent of all blacks born in the U.S. were born in southern states (authors’ calculations from 1980 and 1990 U.S. censuses), which may mitigate some concerns about external validity. Concerns about external validity notwithstanding, this research provides some of the first evidence of the relationship between school quality and health outcomes. Future research that tests for these effects in other contexts, populations, and with other measures of school quality may be valuable. In particular, due to data limitations we are unable to assess whether the effect of school quality on the health returns to schooling is greater at lower levels of school, which may occur if those years are sensitive periods for skill formation (Cunha and Heckman, 2007). As we noted in the Section 2, school quality may affect health through a number of different pathways. Hence, future research may also investigate more of the specific mechanisms linking school quality to the outcomes that we observe.

The nature of studying the effects of school quality on health later in life is that we are constrained to focus on school quality changes that occurred over 50 years ago. Since then, indicators of school quality have substantially improved. For example, the average pupil-teacher ratio in the U.S. in 2000 was approximately half of our sample’s average pupil-teacher ratio, implying that any further class size reductions will take place on a different margin than we observe in our data. Although recent education quality debates include a discussion of school accountability and incentive policies, class size, teachers’ wages, and term length remain an important focus of current education policy. For example, nearly half of all states have enacted class size reduction policies with 12 states amending or establishing new policies since 2000 (Education Commission of the States, 2009). Additionally, teachers’ compensation is an ongoing area of debate as a strategy for retaining effective teachers, providing incentives to improve teaching performance, and for increasing student achievement (Springer, 2009). Further, many school districts increase the length of the school year to provide additional instruction through mandatory summer school for low-achieving students (Matsudaira, 2008). While our results suggest that school quality influences health outcomes, further research is needed to assess whether and to what extent more current school quality policies affect health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Table 8.

Obesity – Potential Mediators

| (1) Base model | (2) Occupation | (3) Income | (4) Insurance | (5) Marital status | (6) All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Pupil-Teacher Ratio | ||||||

| P-T Ratio* Education | 0.000352** (0.000137) | 0.000270* (0.000132) | 0.000322** (0.000140) | 0.000338** (0.000133) | 0.000355** (0.000136) | 0.000263* (0.000133) |

| Observations | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 |

| R-squared | 0.041 | 0.044 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.044 |

| Panel B. Teacher Wages | ||||||

| Wages* Education | −0.00119** (0.000433) | −0.000920** (0.000402) | −0.00108** (0.000439) | −0.00112** (0.000417) | −0.00119** (0.000433) | −0.000888** (0.000405) |

| Observations | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 |

| R-squared | 0.041 | 0.044 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.044 |

| Panel C. Term Length | ||||||

| Length* Education | −0.00118** (0.000409) | −0.000896** (0.000363) | −0.00108** (0.000387) | −0.00113*** (0.000385) | −0.00118** (0.000409) | −0.000877** (0.000339) |

| Observations | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 | 34490 |

| R-squared | 0.041 | 0.044 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.044 |

Footnotes

This project was funded, in part, by the National Institute of Mental Health, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Emory University Woodruff Funds, and the Emory Global Health Institute. We thank Linda Carter, Len Carlson, Sandy Darity, Daniel Eisenberg, Jason Fletcher, Sarah Gollust, Larry Katz, Paula Lantz, Jens Ludwig, Tom McGuire, Ellen Meara, Soheil Soliman, Jacob Vigdor, and participants at the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management conference for helpful comments and discussions. We thank David Card, Jason Fletcher, and Adrianna Lleras-Muney for sharing data about school quality and state characteristics and Carolina Felix for research assistance. We are especially grateful to Stephanie Robinson and Deborah Rose at the National Center for Health Statistics for their assistance with the restricted-access National Health Interview Survey data.

In contrast, MacInnis (2009) and Sansani (2011) use the state-level school quality measures for black and white students combined that are averaged across all individuals born in the decade that are published in Card and Krueger (1992a).

Private philanthropy from the North, particularly the Rosenwald Fund, contributed to the improvements in school quality for blacks in the South during the early 1900s (Margo, 1990; Donohue, Heckman, and Todd, 2002). The Rosenwald Fund targeted states that provided the least amount of funding to black school districts (Donohue, Heckman, and Todd, 2002), which were the states with the historically highest proportion of blacks in the population. However, the Rosenwald Fund also required commitment and support from blacks in the local communities so that the locations that received the most funding could reflect unobserved preferences for education or unobserved parental investments. Since the Rosenwald Fund ended in 1932 and our analysis focuses on school quality between 1936 and 1966, the improvements in school quality due to the Rosenwald Fund do not substantially influence the variation in school quality in our analysis (Donohue, Heckman, and Todd, 2002). For an examination of the impact of the Rosenwald Fund on education outcomes, see Aaronson and Mazumder (2010).

Donohue, Heckman, and Todd (2002) estimate that the litigation by the NAACP explains at least 60 percent of the increase in relative teacher salaries, and also influenced the length of the school year and the pupil-teacher ratio, both absolutely and relatively to whites.

For example, six of these seven states with the highest percentages of blacks in the population around the turn of the century (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina) are the only states with an average pupil-teacher ratio that exceed 40 in 1936. These states also represent the largest improvements in school quality, as shown in Figure 2.

These improvements included the establishment of state boards of health (Cooper and Terrill, 1991), the introduction of water purification systems in major U.S. cities (Cutler and Miller, 2004), the introduction of food programs in schools, and smallpox vaccination requirements for school attendance (Mazumder, 2007).

Results based on cohorts born between 1910 and 1950 are similar to the results shown in the tables below for cohorts born between 1930 and 1950 in the baseline specification, but are not as robust to the inclusion of the additional state characteristics in the full specification.

In the mid-1960s, the increased access to medical care for blacks in the South following the integration of southern hospitals due to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and the financial incentives of the 1965 Medicare Act significantly decreased black infant mortality (Almond, Chay, and Greenstone, 2008). However, these changes in access to care occurred nearly entirely after the cohorts that we study finished their secondary schooling and occurred most prominently in Mississippi.

Our preferred specification includes state-specific linear time trends. However, the results are not sensitive to excluding those terms from the models.

In cases where state of birth data were missing, we augment the self-reported data with state of birth information from the death certificate (if the respondent was from a survey year that collected mortality data and if the respondent died by 2006). However, the latter source of state of birth data accounts for only a very small proportion, less than 1 percent, of the state of birth data.

In 1984, state of birth was only asked of respondents to the Supplement on Aging, so for 1984, only respondents to that supplement are included.

The southern states in our sample include Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

The sample size for smoking analyses is especially small because smoking questions were only asked in a subset of NHIS survey years. In years when smoking questions were asked, they were only asked to the “sample adult” subset of respondents.

Changes in teachers’ wages that were induced by litigation may not represent changes in the qualifications of teachers or quality of teaching. However, Ashenfelter, Collins, and Yoon (2006) note that, although there is little data about teachers’ qualifications, black teachers’ years of schooling completed did increase during this period.

We thank David Card for providing the detailed data used to construct the 10 year averages published in Card and Krueger (1992b). The data between 1936 and 1954 are primarily from the Biennial Surveys of Education, while the data between 1956 and 1966 are primarily from the Southern Education Reporting Service. These are two commonly used sources of data for research examining this period (e.g., Donohue, Heckman, and Todd, 2002; Ashenfelter, Collins, and Yoon, 2006). These data are only available in even years and are averages over all public schools in the state. The number of black pupils and black teachers in each state are reported separately for primary and secondary schools only until 1954; since these school quality measures would only be available for the completed schooling of a few cohorts, we use the average pupil-teacher ratio for all grades.

The average pupil-teacher ratio is constructed as the total enrollment of black students divided by the total number of black teachers in the state. Since this ratio is based on enrollment, instead of attendance, these reported statistics may over-report the number of students present in a classroom. The average teacher wages is the mean wage of all teachers in the state and the average term length is the mean number of days in all schools in the state. Card and Krueger (1992b) note that the average teacher wages reported in the school quality data are nearly identical to the state- and race-specific average wages for teachers in the 1940, 1950, and 1960 Census.

Since the school quality measures are assigned to individuals based on their years of schooling attended and then aggregated for each cohort in each state, the school quality measures are weighted averages of 20 years of school quality data, which reduces the influence of any potential measurement error from a specific year. As noted by Betts (1996), Hanushek, Rivkin, and Taylor (1996), and Heckman, Layne-Farrar, and Todd (1996), state-aggregated school quality measures could lead to an upward bias on the estimated impact of school quality if these measures do not accurately reflect the quality of the actual school attended. On the other hand, Card and Krueger (1996c) note that this type of bias does not exist if changes in school quality at the state level are conditionally exogenous and that state-level measures of school quality could reduce any possible attenuation bias from school-level data that is measured with error or that does not accurately reflect the quality received throughout all years of schooling. We minimize this potential bias by using measures of the quality of schools actually attended by black students in the segregated southern states, as opposed to measures of school quality for all students (e.g., Card and Krueger, 1992a; MacInnis, 2009; Sansani, 2011). However, as noted by Donohue, Heckman, and Todd (2002), the use of state averages of school quality masks variation in school districts within states, which will lead to a downward bias in the estimated impact of school quality; thus, our estimates may be downward biased.

Our results are unchanged if we use IMR measured at the year of birth instead of age 6.

Because self-rated health is an ordered variable, we also estimated these models with ordered probit. The results of these models are qualitatively similar and more precise, and we report OLS models that treat the variable as continuous for ease of interpretation.

The results from probit models are similar.

In addition, we find that for all of our models except for disability, the interactions of the three school quality variables with years of schooling are jointly significant at the 10 percent significance level.

In additional, unreported specifications, we find that the results for males and females separately are qualitatively similar, but that the results for females are greater in magnitude than the results for males.

A one standard deviation decrease in the pupil-teacher ratio of 4.33 students per teacher is equal to 32 percent of the decrease in the pupil-teacher ratio among black schools from 1936 to 1966. A one standard deviation increase in teachers’ wages of $1434 is equal to 33 percent of the increase in teachers’ wages among black schools from 1936 to 1966.

A one standard deviation increase in term length of 11.3 days is equal to 50 percent of the increase in term length among black schools from 1936 to 1966.

We also find some evidence that school quality compresses the BMI distribution by also reducing the likelihood of being underweight, although these results are not significant.

As noted, these models are more likely to be biased due to unobservable variables. In complementary research, we alleviate these concerns by taking black-white differences and find that levels of school quality have modest effects on levels of health outcomes (Frisvold and Golberstein 2010).

We linearly interpolate these measures for the years between decennial censuses.

Only six percent of the same sample migrated to the North.

Following Almond (2005), the survival rate is calculated as the state of birth and year of birth cohort size (derived from the 1980 census), divided by the number of births in the respective cohort (derived from historical vital statistics).

We also note that changes in school quality within states and over time are unrelated to changes in black socioeconomic conditions based on separate regressions of the three school quality measures on five measures of black socioeconomic conditions (percent of adults in the labor force, average family size, Duncan SEI income score, Duncan SEI earnings score, and Duncan SEI occupation score). Of these 15 models, there were only two coefficients that were significant at the 10% level. Given that these two coefficients are in inconsistent directions from each other, that we do not see a clear pattern among the coefficients from the other models, and that only 2 out of the 15 coefficients were statistically significant, it does not seems as if there is a strong systematic correlation between the changes in school quality and the changes in black socioeconomic conditions. One caveat, however, is that these socioeconomic variables are based off of linearly interpolated measures from Census data.

We used a regression-based approach to impute missing values on occupation, income, and insurance status. To impute income (occupation and income), we used out-of-sample predicted values (probabilities) from OLS (multinomial logit) models for the non-missing observations, modeling the outcomes as function of birth year, survey year, age, and marital status.

An alternative approach is to estimate models with these mediator variables on the left hand side to test their potential as mediators. This approach is most straightforward for income, and we do find that school quality increases the income returns to schooling (results not shown). It is less straightforward for the other, categorical, mediator measures.

Because the interaction term is calculated using the mean-centered years of schooling and school quality, the coefficient on years of schooling has the interpretation as the marginal effect of schooling at the sample mean level of school quality.

The magnitude of 0.46 is calculated as 4 × (−0.0953 − 10 × 0.00188).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

David Frisvold, Email: david.frisvold@emory.edu.

Ezra Golberstein, Email: egolberstein@umn.edu.

References

- Aaronson Daniel, Mazumder Bhashkar. The Impact of Rosenwald Schools on Black Achievement. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Working Paper 2009–26 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Aizer Anna, Stroud Laura. Education, Knowledge and the Evolution of Disparities in Health. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 15840 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Almond Douglas. Is the 1918 Influenza Pandemic Over? Long Term Effects of In Utero Exposure in the Post-1940 U.S. Population. Columbia University Working Paper 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Almond Douglas, Chay Kenneth, Greenstone Michael. Civil Rights, the War on Poverty, and Black-White Convergence in Infant Mortality in the Rural South and Mississippi 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Ashenfelter Orley, Collins William J, Yoon Albert. Evaluating the Role of Brown v. Board of Education in School Equalization, Desegregation, and the Income of African Americans. American Law and Economics Review. 2006;8(2):213–248. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS, Mulligan CB. The Endogenous Determination of Time Preference. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1997;112(3):729–758. [Google Scholar]

- Betts Julian. Is There a Link between School Inputs and Earnings? Fresh Scrutiny of an Old Literature. In: Burtless Gary., editor. Does Money Matter? The Effect of School Resources on Student Achievement and Adult Success. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley Hoyt. Disease and Development: Evidence from Hookworm Eradication in the American South. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2007;122(1):73–117. doi: 10.1162/qjec.121.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley Hoyt. Malaria Eradication in the Americas: A Retrospective Analysis of Childhood Exposure. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2010;2(2):1–45. doi: 10.1257/app.2.2.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card David, Krueger Alan B. Does School Quality Matter? Returns to Education and the Characteristics of Public Schools in the United States. Journal of Political Economy. 1992a;100(1):1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Card David, Krueger Alan B. School Quality and Black-White Relative Earnings: A Direct Assessment. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1992b;107(1):151–200. [Google Scholar]

- Card David, Krueger Alan B. Labor Market Effects of School Quality: Theory and Evidence. In: Burtless Gary., editor. Does Money Matter? The Effect of School Resources on Student Achievement and Adult Success. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 1996a. [Google Scholar]

- Card David, Krueger Alan B. School Resources and Student Outcomes: An Overview of the Literature and New Evidence from North and South Carolina. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1996b;10(4):31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Card David, Krueger Alan B. Labor Market Effects of School Quality: Theory and Evidence. NBER Working Paper 5450 1996c [Google Scholar]