Abstract

Mouse and rat chromaffin cells (MCCs, RCCs) fire spontaneously at rest and their activity is mainly supported by the two L-type Ca2+ channels expressed in these cells (Cav1.2 and Cav1.3). Using Cav1.3−/− KO MCCs we have shown that Cav1.3 possess all the prerequisites for carrying subthreshold currents that sustain low frequency cell firing near resting (0.5 to 2 Hz at −50 mV):1 low-threshold and steep voltage dependence of activation, slow and incomplete inactivation during pulses of several hundreds of milliseconds. Cav1.2 contributes also to pacemaking MCCs and possibly even Na+ channels may participate in the firing of a small percentage of cells. We now show that at potentials near resting (−50 mV), Cav1.3 carries equal amounts of Ca2+ current to Cav1.2 but activates at 9 mV more negative potentials. MCCs express only TTX-sensitive Nav1 channels that activate at 24 mV more positive potentials than Cav1.3 and are fully inactivating. Their blockade prevents the firing only in a small percentage of cells (13%). This suggests that the order of importance with regard to pacemaking MCCs is: Cav1.3, Cav1.2 and Nav1. The above conclusions, however, rely on the proper use of DHPs, whose blocking potency is strongly holding potential dependent. We also show that small increases of KCl concentration steadily depolarize the MCCs causing abnormally increased firing frequencies, lowered and broadened AP waveforms and an increased facility of switching “non-firing” into “firing” cells that may lead to erroneous conclusions about the role of Cav1.3 and Cav1.2 as pacemaker channels in MCCs.2

Key words: Cav1.3−/− mouse, action potential firing, pacemaker current, Cav1.2 channels, TTX-sensitive Nav1 channels, BK and SK channels

Introduction

L-type calcium channels (LTCCs, Cav1) contribute to the pacemaker current of central neurons,3–6 neuroendocrine1,7,8 and cardiac sino-atrial node cells9 generating spontaneous action potentials of low frequency (0.5 to 2 Hz) (reviewed in refs. 10 and 11). Between the two LTCCs expressed in these tissues (Cav1.2, Cav1.3), Cav1.3 appears the most suitable isoform for pacemaking in excitable cells: (1) it activates at relatively more negative potentials12–15 and (2) has faster activation but slower and less complete voltage-dependent inactivation.13,14 Using Cav1.3−/− KO mice,12 we found that these peculiarities are well preserved in mouse adrenal chromaffin cells and that Cav1.3 and Cav1.2 contribute equally to the total Ca2+ current (∼25% each).1 Given this, it appears evident that near resting conditions (−50 mV), Cav1.3 is privileged for controlling AP firings with interspike intervals of 0.5 to 2 s (2-0.5 Hz). As suggested by the blocking action of nifedipine on Cav1.3−/− MCCs, we also concluded that Cav1.2 also contributes to pacemaking, but at a lower degree given its more positive voltage range of activation and faster inactivation. A small contribution to the pacemaker current is expected also from TTX-sensitive Na+ channels, which can account for a small fraction of Cav1.3−/− MCCs that preserves their ability to fire in the presence of nifedipine, i.e., when Cav1.2 is pharmacologically blocked and Cav1.3 is absent.1

In apparent contrast with us, a recent paper by Pérez-Alvarez et al.2 reports that Cav1.2 is likely to be the dominant pacemaking channel in MCCs and that Cav1.3 contributes only marginally to the spontaneous activity. The conclusions are based on experiments in WT and Cav1.3−/− KO-MCCs bathed in solutions with higher KCl concentration than ours (5.5 vs. 4 mM) which steadily depolarize the cells by ∼6 mV. Moreover, the authors evaluated the contribution of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 by the block of DHPs at Vh = −80 mV assuming that the same is valid at −40 mV, without taking into consideration that block of LTCCs by DHPs is strongly holding potential-dependent.13,15–17 We show here that the findings by Pérez-Alvarez et al.2 are not in contrast with ours if properly corrected for the different KCl concentration and if DHP blocking potency is suitably tested at the interspike potential of spontaneous firing (à50 mV in 4 mM KCl). Thus, with the proper corrections their data confirm our previous proposal that, near resting physiological conditions the order of importance for pacemaking is: Cav1.3, Cav1.2 and Nav1 channels.

To clarify these critical points, we show here that: (1) full block of Cav1.3 in MCCs requires high doses of nifedipine at Vh = −80 mV (∼30 µM) and 10-fold lower concentrations at Vh = −50 mV, making this channel very sensitive to DHPs near resting conditions, (2) the predominance of Cav1.3 in pacemaking derives from its steep voltage range of activation which is 9 and 24 mV more negative than Cav1.2 and Nav1 channels, respectively, (3) MCCs express only fast and fully inactivating TTX-sensitive Nav1 channels that can contribute little to pacemaker currents lasting 0.5 to 2 s. Saturating doses of TTX block the firing in a small fraction of MCCs (13%), (4) steady depolarizations of ∼6 mV using higher KCl concentrations or few pA of current injection cause a marked reduction and broadening of AP waveform, a 3-fold increase of firing frequency and an increased capability of turning “non-firing” into “firing” cells. These conditions favor the contribution of fast inactivating channels, which activate at more positive potentials (Cav1.2 and Nav1 channels) and introduce serious bias to the true estimate of Cav1.3 role in pacemaking MCCs.

Results

Cav1.3 and Cav1.2 contribute equally to the total Ca2+ current in WT MCCs.

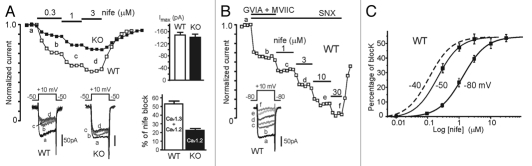

MCCs express both Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 and the two channels together contribute about 50% of the total Ca2+ currents.1,8 It is thus critical to establish the percentage of current carried by each of the two Cav1 channels at the potentials where cells spontaneously fire (−50 mV). We have previously shown that WT and Cav1.3−/− express equal Ca2+ current amplitudes (Fig. 1A top-right inset) and that the block of LTCCs by nifedipine at Vh −50 mV saturates at about 3 µM to give maximal inhibitions of 52.8% (WT) and 22.4% (Cav1.3−/−) (Fig. 1A bottom-right inset). Given the importance of this issue, we show here two examples of L-type current block with increasing doses of nifedipine in WT and KO MCCs held at −50 mV (Fig. 1A). Since WT currents are carried by Cav1.3 and Cav1.2, and KO currents by Cav1.2 alone, it is evident that the DHP effectively blocks both Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 and that Cav1.3 contributes to the total L-type current equally to Cav1.2. The same is not valid when Vh is lowered to −80 mV, where LTCCs sensitivity to DHPs decreases,16,17 requiring higher doses of nifedipine to fully block the channels. Figure 1B shows that after blocking N-, P/Q- and R-type channels with ω-CTx-GVIA (3.2 µM), ω-CTx-MVIIC (10 µM) and SNX-482 (0.4 µM), full block of the remaining LTCCs requires nifedipine concentrations >10 µM. Comparison of the dose response curve of nifedipine action on LTCCs at Vh −80, −50 and −40 mV shows that nifedipine concentrations that mediate complete block of L-type currents at −50 mV or −40 mV can only block a small fraction of current at −80 mV (Fig. 1C). This suggests that using DHP concentrations tested on whole cell Ca2+ currents at −80 mV is not an appropriate basis for arguing on their action on AP firing at interspike potentials near −50 mV or −40 mV, as in the case of reference 2. This procedure would lead to an obvious underestimation of Cav1.3 with respect to Cav1.2.

Figure 1.

Ca2+ current block by nifedipine at different holding potentials (Vh) in WT and Cav1.3−/− MCCs. (A) Time course of normalized peak Ca2+ currents recorded from a WT (open squares) and a Cav1.3−/− MCC (filled squares) before, during and after sequential applications of 0.3, 1 and 3 µM nifedipine. Step depolarization to +10 mV from Vh = −50 mV was applied every 10 s. The insets to the bottom show the current traces recorded at the time indicated by the letters. To the top-right are shown the mean Ca2+ current amplitudes at +10 mV of WT (n = 29) and KO-MCCs (n = 26).1 To the bottom-right are given the percentage of Ca2+ current blocked by 3 µM nifedipine in WT (mean 52.8%; n = 7) and KO MCCs (mean 22.4%; n = 5) (see also ref. 1). (B) Time course of peak Ca2+ currents at +10 mV from Vh = −80 mV recorded from a WT MCC during sequential applications of 3.2 µM ω-CTx-GVIA + 10 µM ω-CTx-MVII C (GVIA + MVII) and 1, 3, 10 and 30 µM nifedipine. SNX-482 (0.4 µM) was constantly applied throughout the experiment to block Cav2.3 channels. The inset shows the current traces recorded at the time indicated by the letters. Notice that nearly full block is obtained only after applying 30 µM nifedipine. (C) Blocking potency of nifedipine Ca2+ currents recorded at Vh = −80 mV and −50 mV in WT MCCs. The dose-response curve at Vh = −50 mV is taken from (C) in reference 1 (IC50 = 0.21 µM; Hill slope 1.2) while the curve at Vh = −80 mV was obtained from ten WT-MCCs (IC50 = 1.31 µM; Hill slope 1.2). Cells were pre-treated with ω-CTx-GVIA (3.2 µM), ω-CTx-MVII C (10 µM) to block N and P/Q-type channels as in (B). SNX-482 (0.4 µM) was added to all solutions containing nifedipine to block also Cav2.3 channels. Step depolarizations were to +10 mV for 20 ms. The dashed curve to the left is an hypothetical dose-response curve at −40 mV drawn just to underline the increased blocking potency of nifedipine at this Vh.

Cav1.3 activates at more negative potentials than Cav1.2 and Nav1 channels.

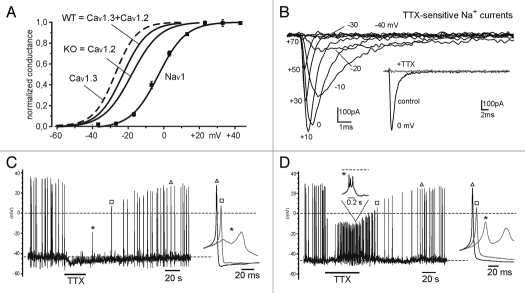

Given that Cav1.3 and Cav1.2 contribute equally to L-type currents, our next issue was to determine the true voltage-dependence of Cav1.3 activation using the conductance vs. voltage curves of LTCCs in WT and KO MCCs previously determined (Fig. 2B in ref. 1). We assumed that the WT conductance curve is a linear combination of the Cav1.3 and Cav1.2 curves with equal weight (50%) and that the KO curve is representative of Cav1.2. The resulting Cav1.3 curve is shown in Figure 2A (dashed line) and appears shifted by about −9 mV from Cav1.2 curve (see legend). This finding together with the observation that Cav1.3 and Cav1.2 contribute equally to the total Ca2+ current and that Cav1.3 inactivates slowly and incompletely during long depolarizations suggest that Cav1.3 outweighs Cav1.2 in pacemaking MCCs.

Figure 2.

Voltage-dependence of Cav1.3, Cav1.2 and Nav1 channel conductance derived from WT and Cav1.3−/− KO-MCCs. The two solid curves with no data points represent the voltage-dependence of WT and KO MCCs Ca2+ conductance taken from reference 1. The dashed curve to the left is the voltage-dependence of Cav1.3 channels obtained by assuming that the WT curve is a linear combination of Cav1.3 and Cav1.2 channel conductance with equal contribution from the two channel isoforms (WT = 0.5 Cav1.3 + 0.5 Cav1.2) and that the KO curve is representative of Cav1.2. The Cav1.3 curve is a Boltzmann function with V1/2 = −26.8 mV and slope factor k = 6.1 mV. The Cav1.2 (KO) curve has V1/2 = −18.1 mV (ref. 1) and is shifted about 9 mV from Cav1.3. The voltage dependence of Nav1 channels was obtained by fitting the mean values of the conductance vs. voltage obtained from families of Nav1 current recordings shown in (B). The Nav1 conductance curve was calculated as Ipeak/(V − Vrev) with Vrev = +70 mV and normalizing to the maximum value at +10 mV (n = 12). The solid curve is a Boltzmann curve with V1/2 = −2.9 mV and slope factor k = 7.7 mV. (B) Overlapped TTX-sensitive Na+ currents recorded from a WT MCC after subtraction of the currents remaining after adding TTX (0.3 µM). K+ and Ca2+ channels were blocked by adding 200 µM Cd2+ to the bath solution and replacing K+ with Cs+ inside the patch pipette. The sequential depolarizations were on step of 10 mV from −40 to +70 mV. They were preceded by a 50 ms depolarization to −50 mV from Vh = −70 mV to partially inactivate the available Na+ channels and attenuate the capacitative artifact. The inset shows a Na+ current trace at +10 mV before and after addition of TT X (0.3 µM). Sustained (non-inactivating) Na+ currents were never observed during pulses of 100 ms duration (n = 12). (C) AP recordings from a WT MCC whose spontaneous activity is fully blocked by TTX (0.3 µM). Notice the slight hyperpolarization and full block of APs during TTX application and the complete recovery after wash out. (D) AP recordings from a WT MCC whose spontaneous activity is altered, but not blocked, by TTX (0.3 µM). The toxin depolarizes by ∼5 mV the firing cell and changes the shape of APs into small bursts of 3 to 5 spikes. This may be explained by a decreased number of active BK channels (due to the reduced Na+-dependent upstroke), accumulation of Ca2+ during the burst and activation of SK channels that terminate the burst. The insets show single or trains of APs recorded at the time indicated on a faster time scale.

Once we established the voltage-dependence of Cav1.3 and Cav1.2 we next studied the gating properties and the range of activation of Nav1 channels that support the upstroke of APs and may contribute to the pacemaker current in MCCs. We found that MCCs express mainly Na+ TTX-sensitive channels that activate at ∼24 mV more positive potentials than Cav1.3 (Fig. 2A) and inactivate fully within tens of milliseconds at all potentials (maximal peak current −635 ± 46 pA at +10 mV, n = 12; Fig. 2B). In twelve MCCs we found no evidence of slowly inactivating “persistent” Na+ channels, which are able to support neuronal pacemaker currents.18 This confirms that Nav1 channels contribute little to the pacemaker current in MCCs (Fig. 3C in ref. 11). Interestingly, when applied to spontaneously firing cells, saturating doses of TTX (300 nM) caused full block only in two out of 17 cells (13%; Fig. 2A). In the remaining 15 cells (87%), TTX caused a 5–6 mV depolarization followed by a persistent firing of smaller APs, often characterized by unusually rapid bursts of three to five spikes (Fig. 2D and legend). In conclusion, fast inactivating Nav1 channels activate at much more positive potentials than Cav1.2 (+15 mV) and Cav1.3 (+24 mV) and contribute little to pacemaking MCCs near resting physiological conditions.

Figure 3.

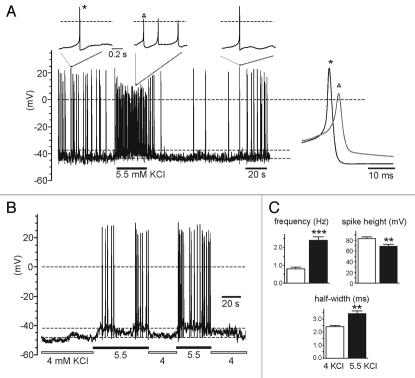

Higher KCl increases the firing frequency, lowers and broadens the AP and turns into “firing” a “non firing” MCCs. (A) Spontaneous firing of a WT MCC in control solution (4 mM KCl) and during a transient increase of KCl to 5.5 mM. Notice the sizeable cell depolarization causing the increased frequency and change of AP shape (lowered spike height and broadened half-width). The insets show single or trains of APs recorded at the time indicated on a faster time scale. (B) A “non-firing” WT cell bathed in control solution (4 mM KCl) generates burst firings when exposed to 5.5 mM KCl. The increased KCl depolarizes the cell by ∼7 mV and favor AP firings. (C) Mean values (±SEM) of firing frequency, spike height and half-width from MCCs in control conditions (4 KCl, empty bar; n = 15) and after applying 5.5 mM KCl (n = 7) or injecting 1–3 pA of current to depolarize the cells by ∼6 mV (n = 8) (5.5 KCl; filled bar). Mean interspike potential was −44.9 mV (4 KCl) and −38.4 mV (5.5 KCl + depo).

Higher KCl solutions or steady depolarizations increase the firing frequency and lowers the AP size.

To assay the true role of Cav1.3 on spontaneous firing, it is important that the cells are maintained near resting physiological conditions, avoiding unnecessary biased potentials which may alter the firing frequency and AP waveform. Either a depolarization induced by 1–3 pA of current injection or bathing the cell in higher than normal KCl solutions changes cell firing and AP waveforms. For instance, ∼6 mV cell depolarization induced by passing 1–3 pA or raising external KCl from 4 to 5.5 mM produces a marked increase of firing frequency, marked reduction of the AP amplitude and pronounced broadening of the half-width (Fig. 3A). In 15 cells (eight depolarized by passing current and seven by raising KCl from 4 to 5.5 mM) we found that AP frequency increased three times (from 0.8 ± 0.1 to 2.4 ± 0.2 Hz; p < 0.001), the height decreased by ∼20% (from 83 ± 3 to 69 ± 4 mV; p < 0.01) and the half-width increased by ∼40% (from 2.4 ± 0.1 to 3.4 ± 0.2 ms; p < 0.01) (Fig. 3C). These altered parameters are comparable to those reported by reference 2 and uncover the different experimental conditions in which this set of data is collected.

Figure 3A also suggests that steadily depolarized MCCs, with higher firing frequencies (3–4 Hz), overrate the role of channels with faster inactivation and higher threshold of activation (Cav1.2 and Nav1) with respect to channels like Cav1.3 that activate at more negative potentials and inactivate slowly. In addition, more positive resting potentials overestimate the percentage of “firing” versus “non-firing” cells, which is a critical parameter to determine whether deletion of Cav1.3 affects MCCs firing. Figure 3B shows an example out of seven in which a “nonfiring” cell in 4 mM KCl is turned into “firing” by simply raising KCl to 5.5 mM. Under these conditions, more positive resting potentials favor the firing of Cav1.3−/− cells, which express only Cav1.2 and possess smaller pacemaker currents than WT MCCs.1 This may explain the larger number of firing Cav1.3−/− KO-MCCs estimated by reference 2 (57%) with respect to us (30%)1 and suggests that most of the different results can be simply explained by methodological differences rather than postulating pathological states of KO mice (see Discussion in ref. 2).

Discussion and Conclusions

The present study extends the work of Marcantoni et al.1 concerning the role of Cav1.3 as pacemaker channel in MCCs. Here we establish unequivocally that Cav1.3 contributes to about half of the L-type current which sustains AP firings near −50 mV and that Cav1.3 activates at 9 mV and 24 mV more negative potentials than Cav1.2 and Nav1 channels. Since TTX-sensitive Nav1 channels are fully inactivating within tens of milliseconds and Cav1.2 inactivates faster and more completely than Cav1.3,13,15 it is evident that Cav1.3 is the most suitable channel for carrying most of the subthreshold pacemaker currents in slow firing MCCs. This does not exclude the possibility that Cav1.2 also contributes to pacemaking these cells. Indeed, KO MCCs lacking Cav1.3 are still able to fire and nifedipine is able to reduce or block the spontaneous firing in most, but not all the KO MCCs.1 This also suggests that besides Cav1.3 and Cav1.2, Nav1 or other ion channels carrying subthreshold inward currents may also contribute to the pacemaker current in a small fraction of cells. Figure 2C clearly shows that this occurs in 13% of cells in which TTX causes a slight hyperpolarization and a block of MCCs firing.

The current study gives also a partial explanation to the contrasting results reported by Pérez-Alvarez et al.2 regarding the marginal role of Cav1.3 as pacemaker channel in MCCs. We showed that this might derive from two anomalous methodological approaches. The first one is the improper use of DHPs that, when tested at Vh −80 mV, underestimate the true contribution of Cav1.3 channels near resting potentials (−50 mV). DHPs have very lowaffinity for Cav1.3 at very negative holding potentials.13–16 Regarding this issue, the use of 0.3 µM nifedipine to identify the contribution of Cav1.2 on AP firing, as proposed by reference 2, is unjustified because this DHP concentration blocks equal fractions of Ca2+ currents in WT and KO-MCCs at −50 mV (see the dose-response curves of Fig. 1C in ref. 1). If 0.3 µM nifedipine inhibits equally Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 a similar block potency of WT and KO firing cells by this DHP concentration cannot be taken as proof that Cav1.2 is the only LTCC pacemaking MCCs. The second one is related to the use of KCl solutions, which depolarize the cell by 5–6 mV, increases the firing and changes the AP shape with marked alteration of cell functioning. As shown in Figure 3, the fraction of “firing” vs. “non-firing” cells can be significantly increased at more depolarized resting potentials. We also cannot exclude that cell firing at higher frequencies (2–3 Hz or 5 Hz as in the case of ref. 2) will increase Ca2+ entry and stimulate Ca2+-dependent pathways that upregulate LTTCs openings19,20 and further contributes to switch “non-firing” into “firing” cells.

In conclusion, to answer the question raised in the title, Cav1.3 is unequivocally a pacemaker channel in MCCs, not secondary to Cav1.2. Most likely its role is not limited to chromaffin cells, dopaminergic neurons6 and cardiac sinoatrial node cells.9 Cav1.3 may even soon result a potential pacemaker channel in other neurons and neuroendocrine cells (reviewed in ref. 10). We also recall that Cav1.3 is particularly coupled to fast inactivating BK channels1 and drives a considerable fraction of SK channels at resting potentials (Vandael DHF, Marcantoni A and Carbone E, unpublished results). Thus, their loss in Cav1.3−/− MCCs is not expected to necessarily reduce the firing frequency as postulated by reference 2, but depending on their coupling to Ca2+-activated K+ channels21,22 it could paradoxically increase it.1

Finally, we would underline the new frontiers on Cav1.3 gating properties associated with the existence of the newly identified short splice variant Cav1.342A,23 whose degree of expression and role in different tissues still needs to be clarified. An important clarification is still expected about the role of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 on catecholamine secretion and vesicles retrieval in which LTCCs are shown to play a critical role (reviewed in ref. 11). Recent data suggest that Cav1.3 contributes more to the exocytosis at low membrane potentials,2,11 in a way resembling T-type Cav3.2 channels.24

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture of WT and Cav1.3−/− mouse adrenal medulla chromaffin cells.

All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines established by the National Council on Animal Care and were approved by the local Animal Care Committee of Turin University. Chromaffin cells were obtained from young (13 months) male C57BL/6N mice. Like for our previous work (ref. 1), Cav1.3−/− mice12 were obtained from the animal house of the Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen (Germany) which breeds animals under SPF conditions and provided us with the respective health certificates that are on file. Animals were killed by cervical dislocation and chromaffin cells were isolated and cultured following the method described previously.8

Voltage-clamp and current-clamp recordings and solutions.

Current-clamp and voltage-clamp recordings were made in perforated-patch conditions using an Axopatch 200-A amplifier and pClamp 10.0 software programs (Axon Instruments Inc., USA). Details on patch pipette fabrication, perforated-patch conditions, current and voltage recordings, filtering and capacitative transient cancellation are given elsewhere in references 8 and 20. The indicated voltages were not corrected for the liquid junction potential. For Ca2+ and Na+ currents the pipette contained (mM): 135 CsMeSO3, 8 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 20 HEPES, pH 7.3 (CsOH) plus amphotericin B. For Ca2+ currents the external bath contained (mM): 135 TEACl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 (with CsOH) and for Na+ currents (mM): 104 NaCl, 30 TEACl, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 (NaOH) plus 200 µM CdCl2. Action potentials (APs) were recorded in current-clamp mode at resting conditions without injecting any current. The intracellular solution contained (mM): 135 KAsp, 8 NaCl, 20 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA pH 7.3 (KOH) and the external bath contained (mM): 137 NaCl, 4 KCl (or 5.5 KCl), 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 (NaOH). The cell perfusion system, all the drugs and toxins were purchased and used as described in references 1 and 24. All the experiments were performed at room temperature (22–24°C). Data analysis and statistical significance were carried out as described previously.1

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Marie Curie Research Training Network “CavNET” (Contract No MRTN-CT-2006-035367), the MIUR (PRIN grant No 2007SYRBBH_001) and the San Paolo Company (grant No 2008.2191).

References

- 1.Marcantoni A, Vandael DHF, Mahapatra S, Carabelli V, Sinneger-Brauns MJ, Striessnig J, et al. Loss of Cav1.3 channels reveals the critical role of L-type and BK channel coupling in pacemaking mouse adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:491–504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4961-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peréz-Alvarez A, Hernández-Vivanco A, Caba-González JC, Albillos A. Different roles of Cav1 channel subtypes in spontaneous action potential firing and fine tuning of exocytosis in mouse chromaffin cells. J Neurochem. 2011;116:195–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson AC, Yao GL, Bean BP. Mechanism of spontaneous firing in dorsomedial suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7985–7998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2146-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson PA, Tkatch T, Hernandez-Lopez, Ulrich S, Ilijic E, Mugnaini E, et al. G-protein coupled receptor modulation of striatal Cav1.3 L-type Ca2+ channels is dependent on a shank-binding domain. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1050–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3327-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puopolo M, Raviola E, Bean BP. Roles of subthreshold calcium current and sodium current in spontaneous firing of mouse midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:645–656. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4341-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan CS, Guzman JN, LLijic E, Mercer JN, Rick C, Tkatch T, et al. Rejuvenation protects neurons in mouse models of Parkinson's disease. Nature. 2007;447:1081–1090. doi: 10.1038/nature05865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcantoni A, Baldelli P, Hernandez-Guijo JM, Comunanza V, Carabelli V, Carbone E. L-type calcium channels in adrenal chromaffin cells: role in pacemaking and secretion. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcantoni A, Carabelli V, Vandael DH, Comunanza V, Carbone E. PDE type-4 inhibition increases L-type Ca2+ currents, action potential firing and quantal size of exocytosis in mouse chromaffin cells. Pflügers Arch. 2009;457:1093–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangoni ME, Couette B, Bourinet E, Platzer J, Reimer D, Striessnig J, et al. Functional role of L-type Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels in cardiac pacemaker activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5543–5548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0935295100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandael DH, Marcantoni A, Mahapatra S, Caro A, Ruth P, Zuccotti A, et al. Cav1.3 and BK channels for timing and regulating cell firing. Molec Neurobiol. 2010;41:185–198. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Comunanza V, Marcantoni A, Vandael DH, Mahapatra S, Gavello D, Navarro-Tableros V, et al. Cav1.3 as pacemaker channels in adrenal chromaffin cells. Channels. 2010;4:440–446. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.6.12866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Platzer J, Engel J, Schrott-fischer A, Stephan K, Bova S, Chen H, et al. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell. 2000;102:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koschak A, Reimer D, Huber I, Grabner M, Glossmann H, Engel J, et al. Alpha 1D (Cav1.3) subunits can form L-type Ca2+ channels activating at negative voltages. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22100–22106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu W, Lipscombe D. Neuronal Cav1.3alpha1 L-type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5944–5951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05944.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helton TD, Xu W, Lipscombe D. Neuronal L-type calcium channels open quickly and are inhibited slowly. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10247–10251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1089-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bean BP. Nitrendipine block of cardiac calcium channels: high-affinity binding to the inactivated state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6388–6392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welling A, Ludwig A, Zimmer S, Klugbauer N, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F. Alternatively spliced IS6 segments of the alpha1C gene determine the tissue-specific dihydropyridine sensitivity of cardiac and vascular smooth muscle L-type Ca2+ channels. Circ Res. 1997;81:526–532. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Do MT, Bean BP. Subthreshold sodium currents and pacemaking of subthalamic neurons: modulation by slow inactivation. Neuron. 2003;39:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00360-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carabelli V, Hernández-Guijo JM, Baldelli P, Carbone E. Direct autocrine inhibition and cAMP-dependent potentiation of single L-type Ca2+ channels in bovine chromaffin cells. J Physiol. 2001;532:73–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0073g.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cesetti T, Hernandez-Gujio JM, Baldelli P, Carabelli V, Carbone E. Opposite action of beta1- and beta2-adrenergic receptors on Cav1 L-channel current in rat adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:73–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00073.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prakriya M, Solaro CR, Lingle CJ. Ca2+i elevations detected by BK channels during Ca2+ influx and muscarine-mediated release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores in rat chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4344–4359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04344.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prakriya M, Lingle CJ. Activation of BK channels in rat chromaffin cells requires summation of Ca2+ influx from multiple Ca2+ channels. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1123–1135. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh A, Gebhart M, Fritsch R, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Poggiani C, Hoda JC, et al. Modulation of voltage- and Ca2+-dependent gating of Cav1.3 L-type calcium channels by alternative splicing of a C-terminal regulatory domain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20733–20744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802254200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carabelli V, Marcantoni A, Comunanza V, de Luca A, Díaz J, Borges R, et al. Chronic hypoxia upregulates α1H T-type channels and low-threshold catecolamine secretion in rat chromaffin cells. J Physiol. 2007;584:149–165. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]