Abstract

The gap junction (GJ) protein connexin (Cx43) is important for organized action potential propagation between mammalian cardiomyocytes. Disruption of the highly ordered distribution of Cx43 GJs is characteristic of cardiac tissue after ischemic injury. We recently demonstrated that epicardial administration of a peptide mimetic of the Cx43 carboxyl-terminus reduced pathologic remodeling of Cx43 GJs and protected against induced arrhythmias following ventricular injury. Treatment of injuries with the carboxyl-terminal peptide was associated with an increase in phosphorylation at serine 368 of the Cx43 carboxyl-terminus. Here, we report that Cx43 peptide treatment of uninjured hearts does not prompt a similar increase in phosphorylation. Moreover, we show that peptide treatment of undisturbed cultured HeLa cells expressing a Cx43 construct also exhibit no changes in Cx43 phosphorylation at serine 368. However, in parallel with the results in vivo, a trend of increasing phosphorylation at serine 368 was observed in Cx43-expressing HeLa cells following scratch wounding of cultured monolayers. These results suggest that peptide-enhanced phosphorylation of the Cx43 carboxylterminus is dependent on injury-mediated cellular responses.

Key words: Cx43, PKC-epsilon, connexon, hemichannel, gap junction

Introduction

Gap junctions (GJs) composed of connexin 43 (Cx43) mediate the direct flow of small molecules and ions (<1,000 Da) between cells. The organization of Cx43 intercellular channels in the heart is thought critical for the transmission of action potentials between cardiomyocytes.1–6 Several groups have demonstrated that remodeling of Cx43 in the setting of myocardial infarct is closely linked to the development of reentrant arrhythmias.7–11 GJ remodeling, which involves loss of intercalated disk-associated Cx43 and redistribution of GJs to the lateral borders of myocytes, is characteristic of myocardium adjacent to an injury.12–15

We recently reported that a cell-permeant peptide incorporating the 9 carboxyl-terminal (CT) amino acids (aa) of Cx43 reduced GJ remodeling and the incidence of induced arrhythmias following cryoinjury of the murine left ventricle (LV).16 This peptide, referred to as αCT1, has been shown to compete with the Cx43 CT for binding the second Postsynaptic density/Disks-large/Zonula Occludens-1 (PDZ) domain of Zonula Occludens-1 (ZO-1).17 αCT1-mediated inhibition of ZO-1 interaction with Cx43 increases GJ size in a cell culture model.17,18 Reports from human studies have demonstrated that Cx43/ZO-1 interaction is increased in human cardiomyopathies,19 suggesting a role for the interaction in disease.20

The rationale for our study investigating the effect of αCT1 on LV cryo-injury was 2-fold: (1) First, as blocking Cx43/ZO-1 interaction reduced remodeling of GJ size in vitro,17,18 we aimed to determine whether targeting this interaction also decreased GJ remodeling in vivo and (2) Second, as αCT1 peptide increased the rate of closure of skin wounds,21 we sought to examine its effects on cardiac tissue repair.6,22

αCT1 treatment reduced ventricular Cx43 remodeling at the injury border zone (IBZ) of cryo-injured hearts and increased the threshold for inducible arrhythmias in these hearts.16 Interestingly, αCT1 also increased the population of Cx43 GJs that were phosphorylated at serine 368,16 a phosphorylation site known to be targeted by protein kinase C (PKC) and associated with cardiac ischemic injury.23 Consistent with these data, αCT1 was found in vitro to increase the phosphorylation of a recombinant Cx43 CT by PKC-epsilon (PKCε) at serine 368 in a dose-dependent manner.16

Here, we report that αCT1 treatment of uninjured LV tissue in mouse does not result in increases in serine 368 phosphorylation, as was observed following cryoinjury. Based on these data it is concluded that increases in Cx43 phosphorylation prompted by αCT1 are likely to be dependent on injury.

Results and Discussion

The observation that treatment with the Cx43 CT mimetic peptide, αCT1 reduced gap junction (GJ) remodeling from intercalated disks in the IBZ and inducible arrhythmias in cryo-injured mouse hearts,16 led us to examine the effects of the peptide on the uninjured mouse ventricle and in HeLa cells expressing Cx43.

In vivo studies.

We previously reported that αCT1 increased the levels of Cx43 phosphorylated at serine 368 in the IBZ of cryo-injured mouse hearts.16 To determine the effect of the peptide in the absence of injury, αCT1 was applied to uninjured hearts, which were subsequently examined for Cx43 phosphorylation at serine 368 by immunofluorescence.

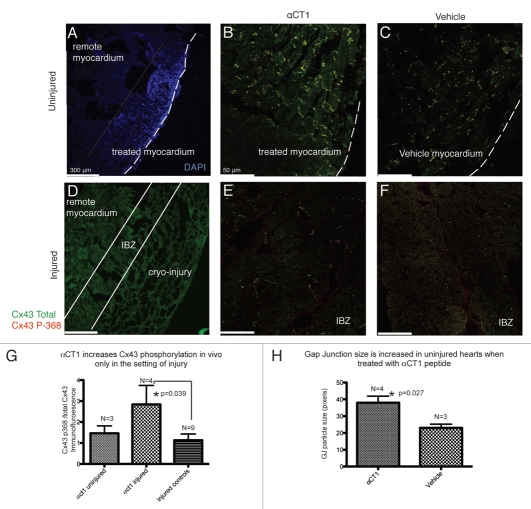

Representative confocal images of immunofluorescently labeled injured and uninjured hearts treated with either αCT1 or vehicle control are presented in Figure 1. Hoechst stain brightly demarcated the site of treated LV myocardium (Fig. 1A) in the uninjured hearts. Bright Cx43 immunolabeling for both total Cx43 and Serine 368 phosphorylated Cx43 was observed predominantly at intercalated disks in the Hoechst-stained region in αCT1-treated and vehicle control hearts (Fig. 1B and C).

Figure 1.

The effects of αCT1 treatment on uninjured and injured hearts (48 hours post-treatment). (A) Uninjured heart labeled with Hoechst stain to identify the region of LV tissue into which peptide elutes. (B) Uninjured heart treated with αCT1 or (C) Vehicle. (D) Cryo-injured LV myocardium demonstrating injury location. (E) Injury border zone (IBZ) of αCT1-treated or (F) vehicle control cryo-injured LV. (G) αCT1 significantly increased P368Cx43/total Cx43 immunolabeling in the IBZ region relative to remote ventricular myocardium. (H) αCT1 increased GJ size in uninjured hearts 48 hours after treatment. Comparisons were computed using an unpaired Student t-test.

The IBZ was readily identified histologically and was defined as the area of myocardium immediately adjacent to the cryo-injury (Fig. 1D). Cx43 expression in this region was substantially lower (Fig. 1E and F) and Cx43 was more lateralized than in remote regions of myocardium, consistent with reports from ischemic cardiac injuries.12,24 Consistent with our previously reported quantification of western blots,16 treatment of cryo-injures with αCT1 and quantification of immunolabeling indicated a significant increase in serine 368 phosphorylated Cx43 relative to total Cx43 at the IBZ normalized to remote myocardium. This increase was not apparent in vehicle or reverse control peptide-treated injured controls or αCT1-treated uninjured hearts (Fig. 1G).

We have previously reported in vitro that αCT1 competes with the CT of Cx43 for binding to ZO-1, and that this competition results in an increase in Cx43 GJ size in vitro.17,18 Consistent with these findings it was determined that treatment of uninjured hearts with αCT1 resulted in a significant increase in Cx43 GJ particle size in vivo (Fig. 1H).

Taken together, these results suggest that there are two distinct effects of αCT1 on GJ remodeling. In contrast to the findings in cryo-injured LV, an αCT1-induced increase in serine 368 phosphorylation was not observed in uninjured hearts. However, GJ size was increased in the uninjured αCT1-treated heart. These results indicate that peptide-mediated inhibition of the Cx43/ZO-1 interaction and its downstream effect on GJ size occurs independent of injury. Conversely, the αCT1-prompted increase in S368 phosphorylation appears to be dependent on the presence of peptide in conjunction with injury.

The results are consistent with studies undertaken by other groups examining Cx43 phospho-status in animal models of cardiac ischemic disease.23,25 In these studies it was demonstrated that preconditioning with transient ischemia23 or a chemical stimulus25 resulted in lateralization of significant fractions of the total Cx43 population away from the intercalated disks along the sides of ventricular myocytes. However, in agreement with what we reported in O'Quinn et al.16 the physiologic or pharmacologic preconditioning stimuli resulted in increased localization of Cx43 phosphorylated at serine 368 at intercalated disks, implicating this phosphorylation site in the cardiac response to injury.

In the uninjured setting there is no induction of Cx43 remodeling and total Cx43, as well as Cx43 phosphorylated at serine 368, are both predominantly found at the intercalated disk (Fig. 1C). One hypothesis explaining this phenomena may be that in the absence of injury, Protein Kinase-C (PKC), the enzyme responsible for phosphorylation at serine 368, is not translocated at sufficient levels to interact with and phosphorylate Cx43. Support for this hypothesis is derived from a study that demonstrated enhanced translocation of PKCε from the cytosol to the particulate fraction in response to ischemia.26

In vitro studies.

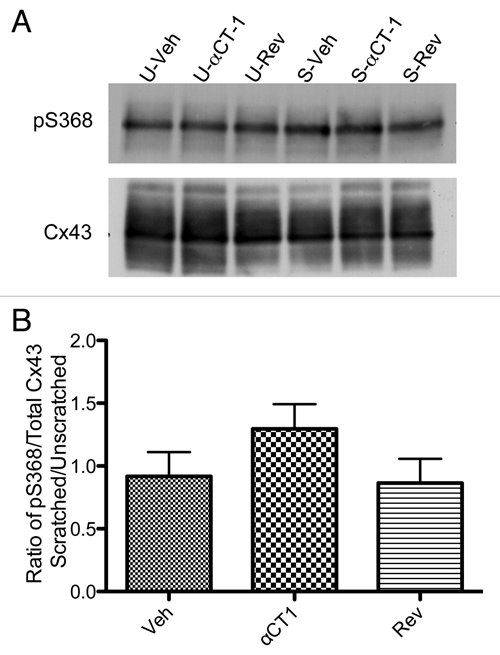

To further probe the injury dependence of αCT1-induced increase in phosphorylation of Cx43 at serine 368, we utilized a cell culture model. Western blotting for S368 phosphorylated Cx43 (Cell Signaling) and pan (total) Cx43 (Sigma Inc.,) was performed on lysates of uninjured and injured (scratched) HeLa cell cultured monolayers and representative blots are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

αCT-1 increases phosphorylation of Cx43 at aa S368 in scratch-wounded Cx43 HeLa cell monolayers. (A) Western blots of S368 phosphorylated Cx43 (top row) and total Cx43 (bottom row) in unscratched (U-) and scratched (S-) Cx43-HeLa cell cultures treated with Veh, αCT-1 or Rev (Reverse peptide control). (B) Densitometric analysis of pS368/Total Cx43 levels in scratched cell monolayers normalized to unscratched controls. Error bars represent standard error (n = 4).

Consistent with the findings in vivo, levels of Cx43 phosphorylated at serine 368 were not detectably different among unscratched groups receiving αCT1, reverse control peptide or vehicle control solutions. However, there was a consistent increase in levels of serine 368 phosphorylated Cx43 relative to total Cx43 in the scratched cell monolayers in all three treatment and control conditions (Fig. 2A). The ratio of scratched to unscratched monolayers of p368/Total Cx43 signal is presented in Figure 2B. Relative to unscratched αCT1-treated wells, the αCT1-treated scratched wells showed a consistent elevation in the Cx43 phospho-isoform over the two control groups (n = 4).

We have recently reported a zone of non-junctional membrane containing connexons linked to ZO-1 proximal to Cx43 GJs that we term the “perinexus”. In this report, we deduced that ZO-1 regulated GJ size by limiting the rate of free connexon accretion into plaques from the perinexus.18 Additionally, inhibition of Cx43/ZO-1 interaction using αCT1 or by ZO-1 siRNA targeting increased junctional Cx43 at the expense of perinexal connexons.18 In ongoing work, it will be of interest to determine patterns of phosphorylation of Cx43 in the perinexus and how the population of ZO-1-interacting connexons in this region responds to injury.

Taken together the results described herein support a dual effect of the Cx43 CT mimetic peptide αCT1 on Cx43 GJ remodeling. The primary and injury independent mechanism is via inhibition of Cx43 ZO-1 interaction and downstream effects on GJ size and reduction of connexon hemichannels proximal to the GJ.18 The second and injury dependent mechanism involves phosphorylation of the Cx43 CT at serine 368, with downstream effects in vivo that include reduced remodeling of GJs from intercalated disks and decreased susceptibility to induced arrhythmias.

Materials and Methods

In vivo studies.

Procedures were performed as described in detail in the supplement of O'Quinn et al.16 with modifications. In brief, Female C57 blk6 or CD-1 mice age 12 to 24 weeks were given a left thoracotomy at the fourth intercostal space to expose the LV free wall. An adherent methylcellulose patch containing 100 µmol/L αCT1 (a peptide containing the CT-most 9 aas of Cx43 17,18 was applied to the anterior free wall of the LV—i.e., the anatomical location on uninjured hearts corresponding to the site of cryo-injury in our previous report in reference 16. The thoracotomy was closed and mice were allowed to recover. After 48 hours the mice were sacrificed and hearts rapidly harvested. A 1 µL aliquot of Hoechst dye was applied to the epicardial surface of the anterior LV free wall to enable identification of the area where the αCT1-eluting patch had been placed.

The hearts were longitudinally hemi-sectioned, rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and frozen fresh in liquid nitrogen-cooled optimal cutting temperature solution. Ten micrometer sections of the LV were fixed and stained for total Cx43 (goat Abcam or mouse IF-1) and Cx43 p368 (rabbit, Cell-Signaling Inc.). Secondary antibodies included Alexa 488 donkey anti-goat or Alexa 488 goat anti mouse and Alexa 594 chicken anti-rabbit (Invitrogen). Single optical sections were obtained using a Leica SP5 laser scanning confocal microscope.

Confluent HeLa cells stably expressing Cx43 (a gift from Dr. Klaus Willecke) were treated with 180 µM of either αCT1, reverse control peptide (Rev, an inactive control peptide with the 9 aas of Cx43 in reverse sequence that we have described previously in ref. 17 and 18) or vehicle control solution (Veh), for 2 hours under culture conditions. Cells were then washed with Hank's buffered salt solution (HBSS; Gibco) without Ca2+ or Mg2+ (HBSS(-)).

In vitro studies.

To simulate injury in vitro, HeLa cell monolayers were scratched in a crosshatch pattern with a No. 11 scalpel (Feather Safety Razor), and cells were incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2. Unscratched cell monolayers were prepared simultaneously in adjoining wells for controls. Cell lysates were then isolated for western blotting as previously described in references 17 and 18. Western blotting was repeated at least four times to ensure reproducibility.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health NIH F30 HL095320 (to Joseph A. Palatinus), The South Carolina Space Grant Consortium (to J. Matthew Rhett) as well as NIH grants HL56728 and HL082802 (to Robert G. Gourdie) and DE019355-01 (PI: Michael J. Yost), and AHA Grant in Aid 87651 (to Robert G. Gourdie). The generous support of Dr. Phil Saul MD, Chief of the Division of Pediatric Cardiology, MUSC is acknowledged with gratitude. The authors also thank Mrs. Jane Jourdan for her outstanding technical support.

Abbreviations

- aa

amino acid

- αCT1

alpha carboxy-terminal 1

- CT

carboxylterminus

- Cx43

connexin 43

- GJ

gap junction

- IBZ

injury border zone

- LV

left ventricle

- PDZ

postsynaptic density/disks-large/zonula occludens-1

- PKCε

protein kinase C epsilon

- ZO-1

zonula occludens-1

Disclosure

Dr. Robert Gourdie is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of FirstString Research Inc., a Charleston biotechnology startup company spun off from his lab at MUSC that has taken αCT1 to clinical trials for indications in skin wound healing. Dr. Gourdie has modest equity (<5% of total) in FirstString Research Inc.

References

- 1.Beyer EC, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Connexin43: a protein from rat heart homologous to a goap junction protein from liver. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2621–2629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gourdie RG, Green CR, Severs NJ. Gap junction distribution in adult mammalian myocardium revealed by an anti-peptide antibody and laser scanning confocal microscopy. J Cell Sci. 1991;99:41–55. doi: 10.1242/jcs.99.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansen JA, van Veen TA, de Bakker JM, van Rijen HV. Cardiac connexins and impulse propagation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delmar M, Coombs W, Sorgen P, Duffy HS, Taffet SM. Structural bases for the chemical regulation of Connexin43 channels. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Severs NJ, Dupont E, Thomas N, Kaba R, Rothery S, Jain R, et al. Alterations in cardiac connexin expression in cardiomyopathies. Adv Cardiol. 2006;42:228–242. doi: 10.1159/000092572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palatinus JA, Rhett JM, Gourdie RG. Translational lessons from scarless healing of cutaneous wounds and regenerative repair of the myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Tamaddon H, Vaidya D, Schneider MD, Chen J, et al. Conduction slowing and sudden arrhythmic death in mice with cardiac-restricted inactivation of connexin43. Circ Res. 2001;88:333–339. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saffitz JE, Schuessler RB, Yamada KA. Mechanisms of remodeling of gap junction distributions and the development of anatomic substrates of arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:309–317. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spach MS, Heidlage JF, Dolber PC, Barr RC. Electrophysiological effects of remodeling cardiac gap junctions and cell size: experimental and model studies of normal cardiac growth. Circ Res. 2000;86:302–311. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poelzing S, Rosenbaum DS. Altered connexin43 expression produces arrhythmia substrate in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:1762–1770. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00346.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wit AL, Duffy HS. Drug development for treatment of cardiac arrhythmias: targeting the gap junctions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:16–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01031.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith JH, Green CR, Peters NS, Rothery S, Severs NJ. Altered patterns of gap junction distribution in ischemic heart disease. An immunohistochemical study of human myocardium using laser scanning confocal microscopy. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:801–821. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters NS, Green CR, Poole-Wilson PA, Severs NJ. Reduced content of connexin43 gap junctions in ventricular myocardium from hypertrophied and ischemic human hearts. Circulation. 1993;88:864–875. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabo C, Yao J, Boyden PA, Chen S, Hussain W, Duffy HS, et al. Heterogeneous gap junction remodeling in reentrant circuits in the epicardial border zone of the healing canine infarct. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao J, Hussain W, Patel P, Peters NS, Boyden PA, Wit AL. Remodeling of gap junctional channel function in epicardial border zone of healing canine infarct. Circ Res. 2003;92:437–443. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000059301.81035.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Quinn MP, Palatinus JA, Harris BS, Hewett KW, Gourdie RG. A peptide mimetic of the connexin43 carboxyl terminus reduces gap junction remodeling and induced arrhythmia following ventricular injury. Circ Res. 2011;108:704–715. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.235747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter AW, Barker RJ, Zhu C, Gourdie RG. Zonula occludens-1 alters connexin43 gap junction size and organization by influencing channel accretion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5686–5698. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhett JM, Jourdan J, Gourdie RG. Connexin43 Connexon to Gap Junction Transition Is Regulated by Zonula Occludens-1. Mol Biol Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruce AF, Rothery S, Dupont E, Severs NJ. Gap junction remodelling in human heart failure is associated with increased interaction of connexin43 with ZO-1. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:757–765. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palatinus JA, O'Quinn MP, Barker RJ, Harris BS, Jourdan J, Gourdie RG. ZO-1 eetermines adherens and gap junction localization at intercalated disks. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00999.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghatnekar GS, O'Quinn MP, Jourdan LJ, Gurjarpadhye AA, Draughn RL, Gourdie RG. Connexin43 carboxyl-terminal peptides reduce scar progenitor and promote regenerative healing following skin wounding. Regen Med. 2009;4:205–223. doi: 10.2217/17460751.4.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhett JM, Ghatnekar GS, Palatinus JA, O'Quinn M, Yost MJ, Gourdie RG. Novel therapies for scar reduction and regenerative healing of skin wounds. Trends in biotechnology. 2008;26:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ek-Vitorin JF, King TJ, Heyman NS, Lampe PD, Burt JM. Selectivity of connexin 43 channels is regulated through protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2006;98:1498–1505. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227572.45891.2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters NS, Coromilas J, Severs NJ, Wit AL. Disturbed connexin43 gap junction distribution correlates with the location of reentrant circuits in the epicardial border zone of healing canine infarcts that cause ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1997;95:988–996. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doble BW, Dang X, Ping P, Fandrich RR, Nickel BE, Jin Y, et al. Phosphorylation of serine 262 in the gap junction protein connexin-43 regulates DNA synthesis in cell-cell contact forming cardiomyocytes. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:507–514. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ping P, Zhang J, Qiu Y, Tang XL, Manchikalapudi S, Cao X, et al. Ischemic preconditioning induces selective translocation of protein kinase C isoforms epsilon and eta in the heart of conscious rabbits without subcellular redistribution of total protein kinase C activity. Circ Res. 1997;81:404–414. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]