Abstract

State owned tobacco monopolies, which still account for 40% of global cigarette production, face continued pressure from, among others, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), to be privatised. This review of available literature on tobacco industry privatisation suggests that any economic benefits of privatisation may be lower than supposed because private owners avoid competitive tenders (thus underpaying for assets), negotiate lengthy tax holidays and are complicit in the smuggling of cigarettes to avoid import and excise duties. It outlines how privatisation leads to increased marketing, more effective distribution and lower prices, creating additional demand for cigarettes among new and existing smokers, leading to increased cigarette consumption, higher smoking prevalence and lower age of smoking initiation. Privatisation also weakens tobacco control because private owners, in their drive for profits, lobby aggressively against effective policies and ignore or overturn existing policies.

This evidence suggests that further tobacco industry privatisation is likely to increase smoking and that instead of transferring assets from state to private ownership, alternative models of supply should be explored.

Keywords: Privatisation, tobacco industry, public policy, tobacco control

Introduction

The increase in global smoking rates is attributable in large part to the spread of transnational tobacco companies (TTCs). TTCs enter new markets in two main ways: by exporting to the market (facilitated by trade liberalisation) or by producing in the market - through foreign direct investment (FDI) and privatisation of state owned tobacco monopolies (SOTMs), made possible as a result of investment liberalisation (McCorriston 2000).

Studies of the forced opening of four Asian cigarette markets to American cigarette exports in the 1980s indicate that removing barriers to trade leads to higher cigarette consumption by increasing competition, which drives marketing activity up and prices down (Taylor and Chaloupka 2000). By contrast, there has been less research on investment liberalisation and privatisation of SOTMs.

Numerous SOTMs have been privatised in recent years, sometimes as a result of International Monetary Fund (IMF) pressure (Weissman and White 2002). Despite the uniquely damaging nature of tobacco, the IMF appears to apply the same rationale to privatisation of tobacco and other industries (Gilmore, A. et al. 2009), even though staff have acknowledged in private that privatisation will likely increase competition, reduce costs and increase marketing – all likely to stimulate cigarette consumption (personal correspondence IMF staff member, October 2005). The IMF’s response has been to advocate tax increases, at best only a partial response, and one to which countries do not seem to have paid much attention (Stuckler et al. 2010). IMF staff and supporters of tobacco industry privatisation instead argue, in line with economic concepts, that governments no longer directly engaged in selling tobacco will be more likely to adopt effective tobacco control measures (personal correspondence IMF staff member, October 2005) (Chaloupka and Nair 2000b).

Although the Chinese tobacco monopoly is by far the largest, state owned tobacco companies remain common in many parts of the world (Mackay and Erikson 2002, Yurekli and De Beyer 2002), accounting for an estimated 40% of world cigarette consumption (Mackay and Erikson 2002). The pressure to privatise these entities makes it essential to understand the potential impacts. Presently, what is known about privatisation is contained in isolated case studies making it difficult to assess overall effects. This paper addresses this issue by reviewing the existing evidence on the impacts of FDI in and privatisation of state owned tobacco manufacturing assets.

Background

Privatisation

Privatisation is defined here as the deliberate sale by a government of state-owned enterprises or assets to private economic agents. By the early 1990s the belief that publicly owned assets would perform more efficiently in private ownership was a core component of the macroeconomic reforms exported globally by the World Bank and IMF despite a marked absence, at the time, of evidence of the impacts of privatisation (Stiglitz 2002).

Evidence emerging subsequently shows that private firms outperform state owned enterprises in efficiency and profitability and that privatisation leads mostly to improvements in operating and financial performance (Megginson and Netter 1998, Nellis 1999). While most evidence comes from high income countries, some multi-country surveys and individual studies from low and middle income countries reach similar conclusions (Boubraki and Cosset 1998, Nellis 1999). The limitations of the evidence must however be considered. First, there may be selection bias as better performing firms are more likely to be privatised. Second, privatisation may appear to increase efficiency because it occurs contemporaneously with deregulation or competition enhancement (Nellis 1999). Third, most studies examine impacts at the level of the enterprise with few considering the wider societal impacts, including on workers, the environment, the distribution of wealth and health (Nellis 1999, Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids 2005)or economic growth (Havrylyshyn and McGettigan 1999a). Finally, studies from the former Soviet Union (FSU) show few benefits and it appears that benefits of privatisation decline in the less developed parts of this region, consistent with evidence that privatisation is more likely to go wrong in poorer countries (Nellis 1999, Cook and Unchida 2001).

Privatisation post communism

When communism collapsed around 1990, privatisation was a key part of the economic reforms promoted by the IMF and others (IMF 1991, Havrylyshyn and McGettigan 1999b). The recommended ‘shock therapy’ approach of rapid privatisation assumed that implementation of competitive policies and institutional safeguards could follow privatisation (Sachs 1992, Lavigne 2000, Stiglitz 2002). But the failure of these economic reforms was catastrophic. In Russia, for example, GDP in 2000 was less than two-thirds that of a decade earlier and the proportion of the population living in poverty increased from 2% to 24% between 1989 and 1998 (Stiglitz 2002). A large cross-national study found that the extent of mass privatisation was significantly associated with increased adult mortality (Stuckler et al. 2009).

Subsequent re-assessments have led IMF and World Bank officials to acknowledge that privatisation failed in the FSU, although this failure has largely been attributed to the context of privatisation, notably weak and corrupt governments and under-developed institutional structures (Havrylyshyn and McGettigan 1999a, Havrylyshyn and McGettigan 1999b, Nellis 1999), while the role that corporations may have played has been largely overlooked (Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2007b).

Methodology

An initial review of the literature on the impacts of privatisating tobacco manufacturing industries was conducted in February 2007. Medline and Embase databases were searched using the terms privatisation/privatization, market opening, trade liberalisation/liberalization and market liberalisation/liberalization, combined with ‘tobacco industry’ or ‘tobacco’. Google searches were performed and experts working the subject area or in countries where tobacco privatisation had occurred, were contacted to obtain any grey literature. Appropriate citations from the literature identified were also obtained. The searches of Medline and Embase were updated in August 2010.

The review focused on both the economic impacts of privatising tobacco manufacturing assets (examining evidence of effects on government revenue, market competition, employment and trade) and also its impacts on public health (changes in cigarette marketing and price, tobacco control policy and finally cigarette consumption and smoking prevalence).

The literature identified primarily covered transition economies in Europe and Eurasia (the FSU countries and Hungary), although some studies addressed privatisation/FDI in Austria, Turkey and Cambodia. Exploring the effects of privatisation in Turkey (February 2008) raises different issues to elsewhere as the privatisation of Tekel, the SOTM, agreed in February 2008 (Attwood 2008), was preceded by 16 years of investment liberalisation (Weissman and White 2002, Yurekli and De Beyer 2002). Papers focusing on the impacts of trade liberalisation (in Thailand, Japan, Taiwan and Korea), including those where privatisation and trade liberalisation almost coincided and thus the two impacts could not be disentangled, were excluded from the review (e.g. Sato et al. 2000, Hsu et al. 2005; Wen et al. 2006, Lee et al. 2009). For the same reason, data on Austria, where privatisation (in 1997) followed EU accession (1995) and thus trade liberalisation, were excluded (Bachinger 2004). Other countries known to have undergone privatisation did not feature in the literature and could not therefore be included in the review. In total 24 peer reviewed research papers were included, one thesis (with a second one excluded), five published reports, three book chapters, one unpublished report and one World Bank briefing.

To assess the extent to which the literature is representative of tobacco industry privatisations we also obtained information on privatisations of state owned tobacco manufacturers undertaken since 1991 (see Table 1). This involved searching the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency’s FDI database (http://www.fdi.net), Euromonitor (http://www.euromonitor.com), industry press releases, rulings of competition authorities, company web-sites, industry documents, trade journals, newspaper articles, academic reports, and WHO publications. We also acquired data directly from Ministries of Finance, tobacco control advocates and academics. Given that the impact of FDI/privatisation will likely depend on the extent of change in the tobacco market engendered through the privatisation process (i.e. the degree of change in share ownership), we used the same sources to obtain information on market share immediately prior to privatisation in order to assess whether the enterprise being sold had a leading share of the cigarette market. Although our searches aimed to uncover all tobacco industry privatisation, for simplicity and because this was consistent with the literature identified above (which focused almost exclusively on the impact of privatising cigarette manufacturing assets), we include in Table 1 only those privatisations involving cigarette manufacturing1. The data indicate that the studies included in our review cover 15 of the 37 countries in which privatisation has taken place since 1991 and focus predominantly on countries where the industry being privatised had a leading market share (covering 11 out of 25 of these countries) or where the market share was unknown (three countries); the only exception being Turkey where, as a result of the preceding investment liberalisation, by the time the SOTM was sold it no longer had a leading market share. The fact that the literature obtained focused heavily on countries in the FSU and Eastern Europe largely reflects the fact that most tobacco industry privatisations occurred in this region.

Table 1.

Privatisations of state owned cigarette manufacturers since 1991 where the enterprise was a dominant or monopoly producer and privatisation led to control1 of the company being ceded to the private sector2

| Country (region) | Included (I)/Excluded (E)3 | Year of privatisation4 | Domestic (legal) market share | Method of privatisation5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Former state owned enterprises having leading dominant or monopoly (legal) markets shares | ||||

| Hungary (Europe) | I | 1991 | Monopoly | Philip Morris (PMI), Austria Tabak, (Japan Tobacco) Reemtsma (Imperial), BAT, RJR Nabisco (Japan Tobacco). |

| Ukraine (Europe) | I | 1992 | Monopoly | RJR Nabisco (Japan Tobacco), Reemtsma (Imperial), BAT, Philip Morris (PMI) |

| Russian Federation (Europe) | I | 1992 | Monopoly | RJR Nabisco (Japan Tobacco), Philip Morris (PMI), Rothmans (BAT), Liggett Brooke (Japan Tobacco), Reemtsma (Imperial). |

| Czech Republic (Europe) | 1992 | Monopoly | Philip Morris (PMI) | |

| Slovak Republic (Europe) | 1992 | Monopoly | Reemtsma (Imperial) | |

| Lithuania (Europe) | I | 1992 | Leading | Philip Morris (PMI) |

| Cambodia (Asia) | I | 1993 | Monopoly | Cambodia Tobacco Company (BAT/joint venture) |

| Estonia (Europe) | I | 1993 | Leading | Svenska Tobaks (Swedish Match) |

| Kazakhstan (Eurasia) | I | 1994 | Monopoly | Philip Morris (PMI) |

| Uzbekistan (Eurasia) | I | 1994 | Monopoly | BAT |

| Japan* | E | 1994 | Leading | Public offering (Japan Tobacco) |

| Albania (Europe) | 1995 | Leading | Share transfers to workers and former owners | |

| France (Europe)* | 1995 | Leading | Public offering (Imperial) | |

| Poland (Europe) | I | 1995 | Leading | BAT, Seita (Imperial), Philip Morris (PMI) and Reemtsma (Imperial) |

| Armenia (Europe) | I | 1995 | Leading | Voucher privatisation |

| Portugal (Europe)* | 1996 | Leading | Philip Morris (PMI) | |

| Tanzania (East Africa) | 1996 | Leading | RJR Nabisco (Japan Tobacco) | |

| Spain (Europe)* | 1998 | Leading | Public offering (Imperial) | |

| Austria (Europe)* | E | 1997 | Leading | Public offering (Gallaher, Japan Tobacco) |

| Kyrgyzstan (Eurasia) | I | 1998 | Leading | Reemtsma (Imperial) |

| Romania (Europe) | 2004 | Leading | Galaxy International/CTSSRL | |

| Korea (Asia)* | E | 2002 | Leading | Public offering |

| Serbia (Europe) | 2003 | Leading | Philip Morris (PMI) | |

| Morocco (Africa) | 2003 | Leading | Altadis (Imperial) | |

| Taiwan (Asia)* | E | 2004 | Leading | Public offering |

| Former state owned enterprises having minority (legal) markets shares or no data | ||||

| Benin (Africa) | 1990 | No data | Rothmans International (BAT) | |

| Latvia (Europe) | I | 1992 | No data | House of Prince (BAT) |

| Ghana (Africa) | 1992 | No data | BAT | |

| Slovenia (Europe) | 1992 | No data | Seita (Imperial) | |

| Peru (South America) | 1997 | No data | No data | |

| Azerbaijan (Eurasia) | I | 1997 | Conflicting data | European Tobacco Incorporated |

| Georgia (Europe) | I | 1998 | No data | No data |

| Ethiopia (Africa) | 1998 | No data | Sheba Investment Holding | |

| Croatia (Europe) | 1999 | Incomplete data | Employee buyout (BAT)/Philip Morris (PMI) | |

| Macedonia (Europe) | 1999 | Conflicting data | Reemtsma (Imperial) | |

| Italy (Europe)* | 2003 | Non Leading | BAT | |

| Turkey (Eurasia) | I | 2008 | Non Leading | BAT |

We use ownership of 50% of the industry or an asset as a proxy for control.

The data in this table have been collated from a number of different sources, including: the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency’s FDI database (http://www.fdi.net), Euromonitor, industry press releases, rulings of competition authorities, company web-sites, industry documents, trade journals, newspaper articles, academic reports, and WHO publications. We have also acquired data directly from Ministries of Finance, tobacco control advocates and academics.

Cells left blank indicate countries where there was no study that could be included.

In many cases state owned cigarette manufacturing capacity is privatised in stages. Privatisation, as such, can occur over many years. We have taken the date of privatisation as the year a controlling interest in a public ‘asset’ (factory, company or industry) was transferred to the private sector. Where a state owned industry is broken up prior to privatisation we have taken the transfer of a controlling interest in the first asset to be sold as our year of privatisation except where the sale of small units occurs in advance of full privatisation (e.g. Bulgartabac’s decision to sell some of its loss-making units, including two cigarette factories) and the state still retains a controlling interest in the remaining industry.

There are several methods of privatisation (which we define here as the transfer of state owned assets to private ownership or control). This column either states the method directly or gives company names (outside of brackets) to denote the commercial beneficiary (beneficiaries when multiple assets were sold separately) of a competitive bid or non-competitive sale or transfer. Companies named in brackets denote current owners where ownership has subsequently changed. Changes in ownership have primarily come about as a result of consolidation in the tobacco industry (for example Reemtsma and Seita have been acquired by Imperial, Rothmans by BAT Austria Tabak, RJR Nabisco and Gallaher by Japan Tobacco.

In Japan, Korea and Taiwan privatisation followed trade liberalisation, whereas in Italy and France (1957), Spain and Portugal (1986) and Austria (1995) privatisation occurred after their accession to the EU.

NOTE: Data on privatisation is difficult to collate not least because in many countries the privatisation process may not be open to public scrutiny and thus assessing the exact date and method of privatisation and change in share ownership can be difficult. The data in this table have been collated to the best of our ability from numerous sources which were triangulated. Where data were not given or were conflicting, and there was no obvious method for assessing the relative strengths of the data, this is stated.

Results

Macro-economic impacts of tobacco industry privatisation

Contribution to FDI and government revenue

Evidence from the FSU suggests that tobacco industry privatisation can generate significant revenue for governments (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004c). In the FSU as a whole the TTCs invested over US$2.7billion over the period 1992 to 2000 with the contribution of these tobacco investments to total FDI varying widely by country, from around 1% to over 30% in Uzbekistan where British American Tobacco (BAT) remains the largest investor (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004c). Nevertheless it appears that the revenues generated in the short-term from the sale of state owned assets (Deloitte and Touche 2002) and in the longer term through various tax revenues, were less than anticipated for a number of reasons. For example, TTCs have actively sought to limit the prices paid for SOTMs by preventing competitive tenders (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004b, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2007b), have negotiated highly favourable tax treatment (tax holidays, notably profit tax holidays, were, for example, obtained in Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Hungary and Kyrgyzstan) (Deloitte and Touche 2002, World Bank 2005, Gilmore, A.B. et al.2007b) and, by their complicity in large scale smuggling operations to avoid import and excise duties and lobbying to reduce excise rates (see below), have further reduced government revenues (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004a). Smuggling also undermines local firms, which can then be acquired more cheaply (Shepherd 1985).

Although much of this evidence comes from the FSU, other research suggests BAT was able to negotiate similar investment incentives in Cambodia, thus reducing the cost of its investment (McKenzie et al. 2004).

Competition

Competition is generally assumed to be an inevitable consequence of privatisation. Yet TTC influence appears to limit the extent to which privatisation produces competitive markets (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004c, McKenzie et al. 2004, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2005, World Bank 2005, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2007b). In the five FSU countries, for example, manufacturing monopolies were established post-privatisation and a de facto monopoly established elsewhere despite other companies investing (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004c). One reason is that TTCs use their political influence actively to shape their operating environment. Reemtsma (now part of Imperial Tobacco), for example, obtained an undertaking from the Kyrgyzstan government that it would be the sole domestic producer of cigarettes (World Bank 2005). In Uzbekistan, BAT established a manufacturing monopoly and constrained both domestic and external competition through various routes including absorbing potential internal competitors, securing exclusive rights to manufacture, erecting barriers to market entry and establishing exclusive deals with local distributors, whilst simultaneously negotiating exclusion from the monopolies committee (Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2007b).

Yet, regardless of the underlying market structure emerging post-privatisation, TTCs have acted, in terms of their marketing practices, as though operating within a competitive environment, as explored further below.

Employment in the tobacco sector

As might be expected given that capital investment increases labour productivity, Ukrainian data show that total tobacco industry employment fell between 1995 and 2000 (the first TTC investment was in 1992), with falls concentrated in privately owned factories(Krasovsky et al. 2002) despite marked increases in output (Yurekli and De Beyer, 2002). This pattern is replicated in Turkey and Poland (Yurekli and De Beyer 2002, Zatonksi 2003). There is also evidence of worsening employment conditions among cigarette factory workers (Krasovsky et al. 2002) and tobacco farmers (British Helsinki Human Rights Group 2002). While it is possible that increased employment in sales and marketing might offset declines in manufacturing, this has not been examined.

Cigarette production and tobacco trade

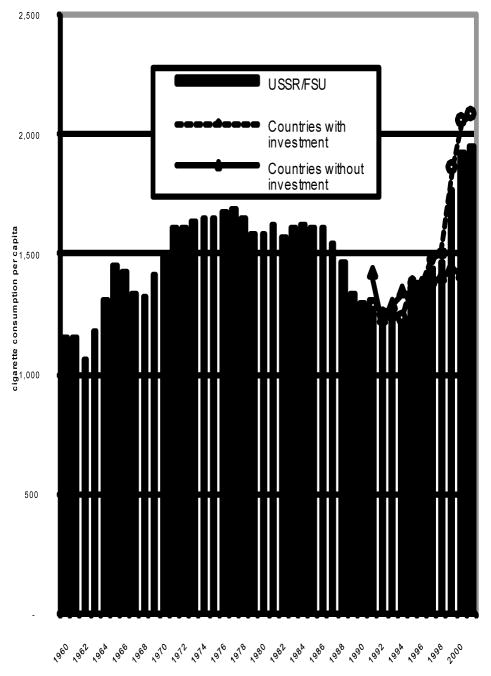

Analysis of data from the FSU and Turkey indicates that FDI transforms the economics of cigarette production and trade (Yurekli and De Beyer 2002, Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2005). Cigarette production capacity in FSU factories receiving private investment tripled following investment. As most factories operated well below capacity pre-investment, actual increases in production were likely to be far higher (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004c). This is supported by data showing the largest increases in production where TTCs had invested: a 96% increase between 1991 and 2000 in the seven FSU countries that received investment prior to 1997 compared with just 11% in those without investment by 20002 (see Figure 1) (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2005). In Ukraine, increased production was seen exclusively within the privatised factories (Krasovsky et al. 2002) while in Turkey the increase post 1992 was more marked in private producers (Yurekli and De Beyer 2002).

Figure 1.

Cigarette Production in the USSR/FSU, 1960–2001

Source: USDA data, Figure taken from Gilmore, A.B. and McKee (2005). Note:2001 data are estimates.

Significantly, in the FSU, the only region where this has been examined, the massive growth in production had little impact on the balance of trade as most of the increase was consumed locally (see below), leaving little surplus for export. Although exports increased through the 1990s, imports still substantially outweigh exports by around 2.5 to 1 across the region (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee, 2005).

The rapid increase in cigarette production and the shift in output from local (based on locally grown leaf) to international cigarettes (largely requiring forms of tobacco leaf not grown locally) has led to massive increases in leaf imports in countries receiving TTC investments (see Figure 2) (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2005) and a fall in local leaf production to below levels seen in the Soviet era (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2005). As a result, the regional trade deficit in tobacco leaf increased ten-fold between 1992 and 1999 (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2005). This challenges the TTC’s claims that privatisation would improve tobacco leaf agriculture and lead to leaf import substitution (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004b) and, at least in Poland, this contributed to a decline in agricultural employment (Zatonksi 2003).

Figure 2.

Tobacco leaf imports, USSR/FSU 1960 to 1999 (in metric tons)

Source: UN FAO Agricultural food and trade database, taken from Gilmore, A.B. and McKee (2005).

The only work so far on the economic implications of these changes suggests that between 1996 and 2000 in Ukraine, the cost of tobacco imports exceeded export earnings by US$525 million, US$100 million more than tobacco excise revenue for the same period. Although the balance has improved since 1999, the trade deficit remains substantial (Krasovsky et al. 2002).

Public health impacts of tobacco industry privatisation

Marketing practices

SOTMs do not traditionally market their products actively as their monopoly position makes it unnecessary, although some also face legal restrictions on tobacco advertising. Overwhelming evidence from every country where this issue has been examined, including most of the FSU, Hungary, Poland and Cambodia, shows that privatisation produced fundamental changes in the marketing environment. The TTCs launched massive cigarette marketing campaigns and were consistently ranked among the top advertisers in all countries with available data (Zatonksi 2003, Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004c, McKenzie et al. 2004), targeted key groups – women, young people, those living in the cities, and opinion leaders (Szilagyi and Chapman 2003a, Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004a, McKenzie et al. 2004, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2005, Le Gresley et al. 2006, Perlman et al. 2007) -- and flaunted or overturned marketing restrictions (Krasovsky 1998, Szilagyi and Chapman 2003a, Zatonksi 2003, Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004c, McKenzie et al. 2004, Szilagyi and Chapman 2004, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006, Le Gresley et al. 2006). In 1995 in Hungary, for example, the Consumer Protection Agency (CPA) found cigarette producers had violated tobacco advertising bans in almost all media (Szilagyi and Chapman 2003a).

The TTC’s own documents show that their underlying aim was to expand the market by driving up consumption and increasing the number of new smokers (Szilagyi and Chapman 2003a, Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004a, Szilagyi and Chapman 2004, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2005, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006). The ambitious targets the TTCs set themselves, which were predicated on having no advertising restrictions (Szilagyi and Chapman 2003a, Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004a, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006), and included, for example, a 45% increase in consumption in Uzbekistan to be achieved between 1993 and 1999 (Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006), appear to have been reasonably accurate given the subsequent trends in consumption (explored below).

Similarly, FDI by the TTCs in Turkey was (according to work by both the World Bank and WHO) followed by aggressive marketing with promotional efforts aimed at children and young people (Yurekli and De Beyer 2002, Bilir et al. 2009). These observations are consistent with industry document evidence of intensive marketing and the importance of young, female smokers to the TTCs (Lawrence 2008). Such efforts contrasted with the previous state monopoly era and were associated with rises in consumption and prevalence (Yurekli and De Beyer 2002, Bilir et al. 2009).

Importantly, and in contrast to SOTMs, the TTC’s approach to marketing seems independent of the degree of competition in a market. Thus BAT planned and executed (Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006) aggressive marketing campaigns even in markets where it hoped to, or had successfully established, private monopolies (Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2005, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2007b).

Cigarette prices

There has been little published work on the impact of privatisation on cigarette prices and none assessing the impact of resulting price changes on consumption. What data exist suggest that cigarette prices have fallen post-privatisation. Work in Russia and Ukraine shows that cigarette prices fell by some 30% to 50% in real terms between 2000 and 2006/7 (Ross et al. 2008, Ross et al. 2009). This was a period in which these economies, having collapsed during the 1990s, were starting to grow again and thus incomes and the cost of staples such as bread were rising. As a result, cigarettes have become more affordable (Ross et al. 2008, Ross et al. 2009). Analyses from Turkey suggest real prices fell from 1987 to 2000 although these falls were almost exclusive to TTC’s brands as real prices of local brands remained fairly stable (Onder 2002).

Such trends are consistent with evidence of the TTCs largely successful efforts to reduce excise rates (see next section), their use of price discounting (Szilagyi and Chapman 2003b) and smuggling, with evidence that the majority of TTC cigarette imports to the FSU in the early 1990s were smuggled (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004a, Gilmore, A. et al. 2007a).

Tobacco control policies

In addition to the flaunting of existing legislation, described above, literature from the countries in which privatisation was examined shows that privatisation led to highly effective lobbying against the introduction of new tobacco control measures (Szilagyi and Chapman 2003a, Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004a, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006), with TTCs focusing on preventing advertising restrictions, reducing excise rates and shaping excise policy (Zatonksi 2003, Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004c, McKenzie et al. 2004, Szilagyi and Chapman 2004, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006, Gilmore, A. et al. 2007a). In Uzbekistan, for example, BAT, having already reversed an advertising ban in the capital, Tashkent, overturned potentially highly effective national legislation which, inter alia, banned cigarette advertising and smoking in public places, having the advertising ban replaced with an ineffective voluntary code (Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006). BAT also redesigned the Uzbek tobacco taxation system to reinforce its monopoly, reduce competition and, ultimately, boost sales earnings, securing, amongst other changes, a 50% reduction in cigarette excise rates (Gilmore, A. et al. 2007a).

Although it could be argued that, as the largest single source of FDI (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004c), BAT may have enjoyed particularly strong leverage in Uzbekistan, other evidence suggests TTC efforts to manage regulation were systematic. BAT established a unit specifically to provide advice to recipient governments on tobacco excise regimes (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004b) and attempted to influence tax policy wherever it sought to invest, with documented attempts in Hungary, Belarus, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and Cambodia (Szilagyi and Chapman 2003b, McKenzie et al. 2004, Szilagyi and Chapman 2004, Gilmore, A. et al. 2007a). Other TTCs elsewhere obtained similar concessions as condition of investment (Szilagyi and Chapman 2003a, Szilagyi and Chapman 2003b, Zatonksi 2003, Gilmore, A. et al. 2007a). Collaboration among TTCs to promote voluntary advertising codes as a means of avoiding more stringent legislation has been documented in Russia, Ukraine, Hungary and Cambodia (Szilagyi and Chapman 2003a, McKenzie et al.2004, Szilagyi and Chapman 2004, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006) and the reversal of a Soviet decree banning tobacco advertising appears to have been a precondition for the deal by RJ Reynolds and Philip Morris to import 34 billion cigarettes to the Soviet Union in the early 1990s (Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006). Poland’s example, however, illustrates that the industry’s capacity to fashion policy is not absolute. As elsewhere, privatisation was initially followed by weakened tobacco control, with lower tax rates and weakened advertising restrictions offered as concessions to TTCs (Zatonksi 2003). But when this adversely affected smoking trend in the early 1990s -- the previous decline in smoking prevalence halted, the percentage of occasional smokers and young female smokers increased (Zatonksi 2003) – Poland, unlike other countries in transition, responded rapidly, implementing a series of tobacco control measures (Zatonksi 2003, Zatonski 2004). Another complex example is Turkey. Although it is clear that, following market entry in 1993, the TTCs both undermined existing legislation and lobbied to obstruct new tobacco control legislation, their lobbying was not always successful and policies did progress most notably with the launch of the National Strategy for Tobacco Control in December 2007 (Lawrence 2008, Bilir et al. 2009, Yurekli and De Beyer 2002). Shortly preceding the privatisation of Tekel in June 2008, this development reflects the strong domestic advocacy for tobacco control (Bilir et al. 2009).

Cigarette consumption

Although detailed econometric analyses of the impacts of privatisation have not yet been undertaken due, in the FSU at least, to the complexity of interpreting economic data during periods of rapid inflation, the introduction of new currencies and redenomination of old ones (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee, 2005), one study published on the FSU (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2005) and another unpublished report on Turkey and Ukraine (Yurekli and De Beyer 2002), suggest that privatisation/FDI increases consumption. From historic lows in the early 1990s, immediately prior to privatisation, cigarette consumption grew rapidly in the FSU with increases concentrated in countries where TTCs invested: between 1991 and 2000, an increase in per capita consumption of 56% occurred in the seven countries receiving early investments, whilst a fall of 1% was seen in the five countries that remained without investment (see Figure 3) (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2005). Although differences in the volume of smuggling between these two groups of countries may have been substantial, they are unlikely to account for differences in consumption of this magnitude. Increases of this order seen both in the FSU (Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2005) and Turkey (Yurekli and De Beyer 2002) at a time of major economic recession is remarkable. So too is the fact that consumption increased in Turkey despite robust tobacco control policies, seemingly in large part attributable to the TTCs willingness to circumvent them.

Figure 3.

Cigarette consumption per capita in the USSR/FSU (all ages), 1960–2001

Source: Cigarette consumption -USDA data. Population data -UN data to 1989, WHO data from 1990. Adapted from Gilmore, A.B. and McKee(2005). Note:2001 data are estimates.

Smoking prevalence

The most important evidence of a positive association between privatisation and prevalence comes from a large Russian longitudinal study which reveals a doubling in smoking prevalence among women, from 7% to 15% between 1992 (the year the TTCs first invested) and 2003, and a significant increase from 57% to 63% among men (Perlman et al. 2007). Although a previous study based on repeat surveys of smaller size failed to reach such clear conclusions (Bobak et al. 2006), evidence from Ukraine, where TTC investment occurred from 1992 to 1998, (again based on repeat and not always identical surveys) recorded similar increases in prevalence between 2001 and 2005 (from 12% to 20% in women and 55% to 67% in men) (Andreeva and Krasovsky 2007). One other study assessed trends between 1994 and 1998 in Estonia (TTC investment in 1993) and Lithuania (first TTC investment in 1993), identifying a significant increase in female and male smoking in Lithuania although the latter was not significant once confounders were adjusted for (Puska et al. 2003). Comparison with historical data going back to the 1970s, available only for Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, also suggests marked increases in smoking amongst women (Gilmore, A. 2005). Clearly, privatisation was taking place at a time of major societal change, but it is noteworthy that wherever it has been studied, the increases in female smoking were concentrated among young women in large cities, who were most intensively targeted by the new entrants to the market.

Other surveys provide additional evidence of the impacts of privatisation on smoking habits. A 2001 survey of eight FSU countries identifies key differences in smoking patterns between countries receiving early TTC investments (or in the case of Belarus, treated by the TTCs as though it had) and those that did not (either receiving no investment or late investment) (Gilmore, A. et al. 2004, Pomerleau et al. 2004). The former had significantly (at least 25-fold) higher rates of smoking among the youngest compared with the oldest women, highly suggestive of an increase in female smoking over time. Lower ages of smoking initiation was seen in both this survey, for both genders (Gilmore, A. et al. 2004), and in the Russian longitudinal study for women (Perlman et al.2007). Finally numerous surveys identify urban residence as the most important determinant of female smoking in transition countries post-privatisation (Pudule et al. 1999, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2001a, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2001b, Pomerleau et al. 2004), and trends in the urban/rural gradient over time are entirely consistent with the targeted TTC marketing and distribution strategies detailed above (Perlman et al. 2007).

Discussion

Summary

Most work on tobacco industry privatisation has concentrated on its health rather than economic impacts, with a geographic focus on the FSU and Eastern Europe. Although there was limited evidence from Turkey and Cambodia, other countries, including those in Western Europe, did not feature in the literature (other than an unpublished thesis on Austria which was not included for reasons given above). Much of the literature is also descriptive in nature, either describing policy developments or analysing the TTC’s own documents in order to understand industry behaviour. There are no studies formally assessing the economic impacts of tobacco industry privatisation, few systematically explore impacts on consumption or prevalence over a broad range of countries or link the trends observed with changes in ownership.

Nevertheless, this review identifies several important issues. First, it suggests that tobacco industry privatisation poses a major threat to public health. It appears to increase cigarette consumption and smoking prevalence, especially among young women in urban areas. These increases are associated with major increases in marketing (some specifically targeted at groups with previously low smoking rates), improved distribution, and lower taxes/prices. Increases in female and youth smoking and the fall in age of initiation all signal additional demand for cigarettes created among new smokers and illustrate how TTCs successfully target previously untapped segments of the market. Moreover, marketing appears to occur regardless of the degree of competition in a market. Privatisation also transforms the policy environment because TTCs ignore existing tobacco control policies and undermine implementation of new ones. These impacts all appear to be driven by the for-profit motive of privately owned tobacco companies and underline key differences in behaviour between state and privately owned tobacco companies.

Second, despite the limited economic evaluations, the evidence suggests the economic benefits of privatisation may be lower than commonly supposed. It is clear that TTCs reduced potential government revenue by avoiding competitive tendering, negotiating investment incentives, directing the smuggling of cigarettes and reducing excise rates. Limited evidence also suggests privatisation has not benefitted the balance of trade or employment in tobacco. Furthermore, given evidence that tobacco control is good for a country’s economy (World Bank 1999), the weakening in tobacco control observed, with obvious implications for future health burdens, will have additional negative economic consequences. In short, therefore, the major beneficiaries in this process appear to be the tobacco companies and their shareholders.

Weaknesses and strengths

This review faces the inevitable problems of differentiating the effects of privatisation from those of other reforms undertaken simultaneously, such as price and trade liberalisation, and of ascertaining whether between country differences are genuinely attributable to privatisation. We attempted to reduce this possibility by excluding papers that evaluated changes in countries where tobacco industry privatisation followed trade liberalisation as, given what is already known about the impacts of trade liberalisation, this could skew the results. Nevertheless, this remains a potential issue as much of the evidence obtained focuses on the FSU where tobacco industry privatisation was accompanied by more general and substantial political and market reforms. Publication bias is also a possibility as papers finding no impacts of privatisation may be less likely to be published.

It is possible, for example, that the impacts of tobacco industry privatisation in the FSU were exacerbated by the economic and political disruption, coincident with TTC entry, which likely left governments, focused on state-building and economic reform, unable to prioritise tobacco control. Lack of experience in dealing with powerful corporate lobbying, weak civil society and, in many countries, little real democracy or press freedom would likely have accentuated this. Many of these factors do, however, apply (in various combinations) to many low and middle income countries which could face tobacco industry privatisation in the future. The fact that industry influence occurred in countries such as Hungary and Poland, developing from fundamentally different positions (the countries had been longer established, democratisation had been more successful, FDI was not concentrated in tobacco, etc.), also suggests that policy influence can occur across a range of jurisdictions. Moreover, increases in consumption were seen also in Turkey, seemingly regardless of the strength of pre-existing policies. In fact, the consistency of our findings both across countries and qualitative and quantitative evaluations constitute key strengths of this review.

The only data obtained from Western Europe covered Austria but was excluded from our review as Austria joined the EU just prior to privatisation, making it difficult to disentangle the impacts. Nevertheless it is noteworthy that from 1997/8 (privatisation occurred in 1997) an abrupt increase in sales of over 20% was seen, reversing a 20 year decline (Bachinger 2004), suggesting that similar impacts might be seen in the west. Unsurprisingly, given that both involve the entry of TTCs to new markets, our results are also remarkably consistent with evidence on the impacts of trade liberalisation which indicates that it stimulates cigarette consumption and smoking prevalence through increases in marketing and reductions in price, with the largest increases in smoking occurring in young people and women (Chaloupka and Laixuthai 1996, Chaloupka and Nair 2000a, Honjo and Kawachi 2000, Sato et al. 2000, Taylor and Chaloupka 2000, Hsu et al. 2005).

Validity of arguments for tobacco industry privatisation

This analysis raises serious questions about the validity of two arguments for tobacco industry privatisation – first that it contributes to economic growth, and second, that by taking the sale of tobacco out of state control it creates a policy environment more conducive to tobacco control. A major weakness in such arguments is the overreliance on Poland as an example of the benefits of privatisation on tobacco control (Chaloupka and Nair 2000b). Poland, in our view, is a rare exception. Whilst it is correct that privatisation preceded improvements in tobacco control in Poland, it is incorrect to assume that improvements occurred as a direct result of a change in ownership. In fact, tobacco control weakened in Poland immediately following privatisation, and it was only when the consequences of this became apparent that political action was taken (Zatonksi 2003). A similar response to TTC entry was seen in Thailand and Taiwan in the 1980s and in Turkey in the 2000s – the increase in cigarette consumption and the way TTC marketing undermined existing policies stimulated efforts to strengthen tobacco control despite continued government ownership of the tobacco industry. The key variable explaining improved tobacco control post-privatisation in Poland does not, therefore, seem to be the change in ownership but that public health professionals were sufficiently organised and knowledgeable about tobacco control in advance of TTC entry and could, as a result of meaningful democratisation, influence policy makers (Zatonksi 2003, Zatonski 2004).

The significance TTCs attached to maintaining an unrestricted marketing environment suggests, not surprisingly, that marketing around the time of privatisation is key to creating new smokers. The massive increase in marketing appeared to occur regardless of the underlying market structure. This implies that it is not the presence of competition per se, which drives marketing activity, but the earnings focus of privately owned TTCs. Our findings thus suggest that the pressure to optimise returns to shareholders creates a far more powerful force for driving changes in marketing practices and health policy than the requirement to generate revenue for the state.

Indeed, the very different behaviour of state and privately owned companies is a crucial finding of this review. In their quest for profits TTCs advertise extensively where SOTMs did not. TTCs target marketing to create demand amongst groups with low levels of smoking previously ignored by SOTMs. TTCs circumvent existing legislation and work assiduously to overturn unfavourable legislation and create new favourable legislation in ways that SOTMs did not. Thus, in shifting ownership to the private sector, privatisation augments both the capacity and motivation of the supplier to increase production and marketing and dilute the impact of regulation. In other words, who supplies tobacco products is central to tobacco control. This point, that private ownership of tobacco companies seriously constrains tobacco control because such organisations will always try to undermine tobacco control measures in their drive for profit, has previously been made (Callard et al. 2005a, Callard et al. 2005b).

We do not, however, suggest that state ownership is a panacea for tobacco control. It is not. We simply argue that the evidence suggests privatisation is damaging to public health and, therefore, alternatives to privatisation should be explored as outlined below.

Implications for research and policy

Further research should be conducted in a broader group of countries, including comparisons of countries that have and have not undertaken privatisation of SOTMs, to elucidate more precisely the impacts of privatisation on consumption, smoking prevalence, the economy and society. Nevertheless, we believe there is now sufficient evidence for the IMF to exclude tobacco from investment agreements and lists of state owned enterprises recommended for privatisation. The example of the Thai Tobacco Monopoly suggests that SOTMs can operate reasonably efficiently and profitably. Moreover, despite the growing competitive pressures within that market, the Thai Tobacco Monopoly has yet to contest Thailand’s robust tobacco control measures in the way that TTCs have (Vateesatokit et al. 2000, MacKenzie et al. 2004) and political economists suggest that privatisation could threaten existing tobacco controls (Chantornvong and McCargo 2001). Where there is greater pressure for reform, consideration should instead be given to how tobacco industry restructuring can be achieved without privatisation.(Gilmore, A. 2005) For example, the assets of existing state-owned monopolies might be transferred to a not-for-profit company with legal duties to achieve efficiency savings which are not transferred to the consumer in reduced costs but are instead used to improve tobacco control and drive down consumption. A variety of similar proposals for restructuring or strictly regulating the supply of tobacco have been made but most work from the assumption that this will require restructuring or regulating privately owned companies (Borland, 2003, Callard et al. 2005a, Callard et al. 2005b, Sugarman 2008). Applying these models to SOTMs would not only be easier (precluding the need, for example, to buy out a TTC), but also provide an alternative to privatisation. It should be noted that these models have yet to be applied in practice and, therefore, careful implementation and evaluation of outcomes would be required. We also recognise that the practicalities would be context specific, and in countries where the state-owned company is already in competition with TTCs, success would be more likely where effective tobacco control policies and good systems of governance were already in place. The ratification of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which outlines a set of effective tobacco control policies that all 166 parties to the convention should now implement, could be vital in this regard (World Health Organisation 2003).

Meanwhile, where tobacco industry privatisation does occur, measures can be taken to help ensure that benefits to the public and governments are maximised, and risks to public health are minimised (see Box 1). Recommendations to such effect have been made since 2003 (Gilmore, A. 2003, Gilmore, A.B. and McKee 2004b, Gilmore, A.B. et al. 2006, Gilmore, A. et al. 2007a) and include 2005 World Bank good practice guidelines (World Bank 2005) but do not yet appear to have been acted upon. Evidence from this paper also suggests that these measures can only be achieved in the presence of strict regulation of TTC conduct. The latter could be addressed, at least in part, through Article 5.3 of the FCTC, which aims to reduce the inappropriate influence of the tobacco industry on policy (Conference of the Parties to the FCTC, 2008). In the words of the World Bank, ‘Bank and IMF economists who work on tobacco privatisation need to be as concerned about the government’s ability to regulate as economists who work on telecommunications privatisation must be about creating a regulatory and policy function within the government’ (World Bank 2005).

Box 1. Measures that should be taken to protect countries against the negative impacts of tobacco industry privatisation include.

ensuring that privatisation is preceded by effective tobacco control legislation including comprehensive advertising restrictions, effective excise policies and controls on smuggling;

ensuring that tobacco control legislation includes effective and easily implemented enforcement policies, including high and fiscally significant fines for violation;

ensuring that privatisation deals include agreements that prevent the TTCs from rolling back legislation that has already been put in place;

conducting a health impact assessment (HIA) of the proposed privatisation in order to assess the likely short and long-term health and economic impacts, to identify danger points and mitigate their impact; and

increasing the transparency of privatisation processes and agreements, perhaps through an independent third party, so that ‘deals’ that may undermine economic policy (such as deals to extend profit tax holidays or ensure monopoly status) are avoided.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Cathy Flower for administrative support in preparing the manuscript, and all those who provided us with unpublished reports and responded to requests for information on privatisation.

Funding

AG is supported by a Health Foundation Clinician Scientist Fellowship. Further support was provided by the National Cancer Institute of the United States National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 CA91021-08) and the Wellcome Trust. The funders played no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the paper or decision to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

In reality this led only to the exclusion of a few smaller privatisations such as those of leaf processing units.

Thus excluding three countries where investment occurred after 1997 – considered too soon to have had an observable impact.

Authors’ contributions

Anna Gilmore conceived the idea for the paper, undertook the literature review and wrote the first draft. Gary Fooks undertook the review of tobacco industry privatisations, contributed to the literature review, drafting and editing. Martin McKee contributed to the drafting and revision of the paper and updated the literature review. All approved the final version submitted for publication.

References

- Andreeva T, Krasovsky K. Changes in smoking prevalence in Ukraine in 2001–5. Tobacco Control. 2007;16:202–206. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood A. BAT wins auction for Turkey’s state tobacco firm with $1.72bn bid. The Independent 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Bachinger E. DrPH Thesis. University of London; 2004. Concensus or complacency: The failure of tobacco control in Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Bilir E, Çakır B, Daglı E, Ergüder T, Önder Z. Tobacco control in Turkey. Copenhagen: WHO; 2009. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/98446/E93038.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bobak M, Gilmore A, McKee M, Rose R, Marmot M. Changes in smoking prevalence in Russia, 1996–2004. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:131–135. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R. A strategy for controlling the marketing of tobacco products: A regulated market model. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:374–382. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boubraki J, Cosset J. The financial and operating performance of newly pirvatized firms: Evidenc from developing countries. Journal of Finance. 1998;53:1981–1110. [Google Scholar]

- British Helsinki Human Rights Group. [Accessed 2005];BAT in Uzbekistan. 2002 Available from: http://www.bhhrg.org/CountryReport.asp?CountryID=23&ReportID=5&ChapterID=31&next=next&keyword.

- Callard C, Thompson D, Collishaw N. Curing the Addiction to Profits: A Supply-Side Approach to Phasing out Tobacco. Ottowa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2005a. [Google Scholar]

- Callard C, Thompson D, Collishaw N. Transforming the tobacco market: Why the supply of cigarettes should be transferred from for-profit corporations to non-profit enterprises with a public health mandate. Tobacco Control. 2005b;14:278–283. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. Public Health and International Trade. Washington DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka F, Nair R. International issues in the supply of tobacco: Recent changes and implications for alcohol. Addiction. 2000a;95:S477–S489. doi: 10.1080/09652140020013728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka FJ, Laixuthai A. US Trade Policy and Cigarette Smoking in Asia. Cambridge: 1996. p. 5543. [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka FJ, Nair MK. Alcohol supply: Domestic and international perspectives. International issues in the supply of tobacco: Recent changes and implications for alcohol. Addiction. 2000b;95:S477–S489. doi: 10.1080/09652140020013728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantornvong S, McCargo D. Political economy of tobacco control in Thailand. Tobacco Control. 2001;10:48–54. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conference of the Parties to the FCTC, 2008. Guidelines for implementation of Article 5.3 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control on the protection of public health policies with respect to tobacco control from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry.

- Cook P, Unchida Y. Centre on Regulation and Competition, Working Paper No. 1. University of Manchester; 2001. Privatisation and Economic Growth in Development Countries. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte, Touche for the Alcohol and Drug Information Center Ukraine. In: Economics of Tobacco Control in Ukraine from the Public Health Perspective. Andreeva T, Krasovsky K, Krisanov D, Mashliakivsky M, Rud G, editors. Kiev: Polygraph Center TAT; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, International Monetary Fund, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, and World Bank. A Study of the Soviet Economy. Washington DC: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore A. Tobacco and transition: The example of the former Soviet Union. World Conference on Tobacco or Health; Helsinki. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore A. Thesis (PhD) London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2005. Tobacco and transition: Understanding the impact of transition on tobacco use and control in the former Soviet Union. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore A, Fooks G, McKee M. The IMF and tobacco: A product like any other? International Journal of Health Services Research. 2009;39:789–793. doi: 10.2190/HS.39.4.l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore A, Collin J, Townsend J. Transnational tobacco company influence on tax policy during privatization of a state monopoly: British American Tobacco and Uzbekistan. American Journal of Public Health. 2007a;97:2001–2009. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.078378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore A, Pomerleau J, McKee M, Rose R, Haerpfer CW, Rotman D, Tumanov S. Prevalence of smoking in 8 countries of the former Soviet Union: Results from the living conditions, lifestyles and health study. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:2177–2187. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AB, Collin J, McKee M. British American Tobacco’s erosion of health legislation in Uzbekistan. British Medical Journal. 2006;332:355–358. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7537.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AB, McKee M. Moving East: How the transnational tobacco industry gained entry to the emerging markets of the former Soviet Union - Part I: Establishing cigarette imports. Tobacco Control. 2004a;13:143–150. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AB, McKee M. Moving East: How the transnational tobacco industry gained entry to the emerging markets of the former Soviet Union - Part II: An overview of priorities and tactics used to establish a manufacturing presence. Tobacco Control. 2004b;13:151–160. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AB, McKee M. Tobacco and transition: An overview of industry investments, impact and influence in the former Soviet Union. Tobacco Control. 2004c;13:136–142. doi: 10.1136/tc.2002.002667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AB, McKee M. Exploring the impact of foreign direct investment on tobacco consumption in the former Soviet Union. Tobacco Control. 2005;14:13–22. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AB, McKee M, Collin J. The invisible hand: How British American Tobacco precluded competition in Uzbekistan. Tobacco Control. 2007b;16:239–247. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AB, McKee M, Rose R. Prevalence and determinants of smoking in Belarus: A national household survey, 2000. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2001a;17:245–253. doi: 10.1023/a:1017999421202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AB, McKee M, Telishevska M, Rose R. Epidemiology of smoking in Ukraine, 2000. Preventive Medicine. 2001b;33:453–461. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AB, Radu-Loghin C, Zatushevski I, McKee M. Pushing up smoking incidence: plans for a privatised tobacco industry in Moldova. Lancet. 2005;365:1354–1359. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havrylyshyn O, Mcgettigan D. International Monetary Fund. 1999a. Privatization in Transition countries: A sampling of the literature (WP/99/6) [Google Scholar]

- Havrylyshyn O, Mcgettigan D. Privatization in Transition Countries: Lessons of the First Decade. Washington DC: 1999b. [Google Scholar]

- Honjo K, Kawachi I. Effects of market liberalisation on smoking in Japan. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:193–200. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CC, Levy DT, Wen CP, Cheng TY, Tsai SP, Chen T, Eriksen MP, Shu CC. The effect of the market opening on trends in smoking rates in Taiwan. Health Policy. 2005;74:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasovsky K. Abusive international marketing and promotion tactics by Philip Morris and RJR Nabisco in Ukraine. In: Infact, editor. Global Aggression, the Case for World Standards and Bold US Action Challenging Philip Morris and Nabisco. New York: Apex Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Krasovsky K, Andreeva T, Krisanov D, Mashliakivsky M, Rud G. Economics of Tobacco Control in Ukraine from the Public Health Perspective. Kiev: Alcohol and Drug Information Centre; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne M. Ten years of transition: A review article. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 2000;33:475–483. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence S. Bristish American Tobacco’s failure in Turkey. Tobacco Control. 2008;18:22–28. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.021782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Carpenter C, Challa C, Lee S, Connolly GN, Koh HK. Globalization and Health. 2009;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gresley E, Muggli M, Hurt R. Movie Moguls: British American Tobacco’s covert strategy to promote cigarettes in Eastern Europe. European Journal of Public Health. 2006;16:505–508. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay J, Erikson M. The Tobacco Atlas. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie R, Collin J, Sriwongcharoen K, Muggli ME. “If we can just ‘stall’ new unfriendly legislations, the scoreboard is already in our favour”: Transnational tobacco companies and ingredients disclosure in Thailand. Tobacco Control. 2004;13:ii79–87. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCorriston S. University of Exeter Discussion Paper 00/05. 2000. Recent Developments on the Links between Foreign Direct Investment and Trade. [Google Scholar]

- Mckenzie R, Sopharo C, Sopheap Y. Almost a role model of what we would like to do everywhere: British American Tobacco in Cambodia. Tobacco Control. 2004:ii112–117. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megginson W, Netter J. From state to market: A survey of empirical studies on privatization. Global Equity Markets Conference; Paris. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nellis J. Time to rethink privatization in transition economies. International Finance Corporation Working Paper No. 38. 1999 Available from: http://ssrn.com/abstract=176752.

- Onder Z. Economics of Tobacco Control HNP Discussion Paper No. 2. 2002. The Economics of Tobacco in Turkey: New Evidence and Demand Estimates. [Google Scholar]

- Perlman F, Bobak M, Gilmore A, McKee M. Trends in the prevalence of smoking in Russia during the transition to a market economy. Tobacco Control. 2007;16:299–305. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau J, Gilmore A, McKee M, Rose R, Haerpfer CW. Determinants of smoking in eight countries of the former Soviet Union: Results from the Living Conditions, Lifestyles and Health Study. Addiction. 2004;99:1577–1585. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pudule I, Grinberga D, Kadziauskiene K, Abaravicius A, Vaask S, Robertson A, McKee M. Patterns of smoking in the Baltic Republics. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1999;53:277–282. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.5.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puska P, Helasoja V, Prattala R, Kasmel A, Klumbiene J. Health behaviour in Estonia, Finland and Lithuania 1994–1998. European Journal of Public Health. 2003;13:11–17. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HZ, Shariff S, Gilmore A. Economics of Tobacco Taxation in Ukraine. Paris: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ross HZ, Shariff S, Gilmore A. Economics of Tobacco Taxation in Russia. Paris: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs JD. Privatization in Russia: Some lessons from Eastern Europe. The American Economic Review. 1992;82:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Araki S, Yokoyama K. Influence of monopoly privatization and market liberalization on smoking prevalence in Japan: Trends of smoking prevalence in Japan in 1975–1995. Addiction. 2000;95:1079–1088. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95710799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd P. Transnational corporations and the international cigarette industry. In: Newfarmer R, editor. Profits, Progress and Poverty. Case Studies of International Industries in Latin America. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz J. Globalization and its Discontents. London, Allen Lane: Penguin Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler D, Basu S, Gilmore A, Batniji R, Ooms G, Marphatia A, Hammonds E, McKee M. An evaluation of the International Monetary Fund’s claims about public health. International Journal of Health Services. 2010;40:327–332. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.2.m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler D, King L, McKee M. Mass privatisation and the post-communist mortality crisis: A cross-national analysis. The Lancet. 2009;373:399–407. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman SD. Should we use regulation to demand improved public health outcomes from industry? Yes. British Medical Journal. 2008;337:a1750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi T, Chapman S. Hungry for Hungary: Examples of tobacco industry’s expansionism. Central European Journal of Public Health. 2003a;11:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi T, Chapman S. Tobacco industry efforts to keep cigarettes affordable: A case study from Hungary. Central European Journal of Public Health. 2003b;11:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi T, Chapman S. Tobacco industry efforts to erode tobacco advertising controls in Hungary. Central European Journal of Public Health. 2004;12:190–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A, Chaloupka F. The impact of trade liberalisation on tobacco consumption. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, editors. Tobacco Control in Developing Coutries. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vateesatokit P, Hughes B, Ritthphakdee B. Thailand: Winning battles, but the war’s far from over. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:122–127. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman R, White A. Needless Harm: International Monetary Fund Support for Tobacco Privatization and for Tobacco Tax and Tariff Reduction, and the Cost to Public Health. Washington, DC: Essential Action; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wen CP, Peterson RA, Cheng TY, Tsai SP, Eriksen MP, Chen T. Paradoxical increase in cigarette smuggling after the market opening in Taiwan. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:160–165. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Curbing the Epidemic - Governments and the Economics of Tobacco Control. Washington, DC: 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Privatization in the Tobacco Industry: Issues and good practice guidelines to ensure economic benefits and safeguard public health. 2005 Available from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/HEALTHNUTRITIONANDPOPULATION/Resources/281627-1109774792596/HNPBrief_5.pdf.

- World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yurekli A, De Beyer J. Unpublished report. 2002. Did the entry of private cigarette producers in Turkey and Ukraine increase cigarette consumption? [Google Scholar]

- Zatonksi W. Democracy and health: Tobacco control in Poland. In: De Beyer J, Waverley Brigden L, editors. Tobacco Control Policy: Strategies, successes and setbacks. Six country case studies. Washington DC: World Bank; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zatonski W. Tobacco smoking in central European countries: Poland. In: Boyle P, Gray N, Henningfield J, Seffrin J, Zatonksi W, editors. Tobacco and Public Health: Science and Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 235–252. [Google Scholar]