Abstract

Background

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) can occur in isolation or in association with other abnormalities. We hypothesized that some cases of non-isolated CDH are caused by novel genomic disorders.

Methods and Results

In a cohort of >12,000 patients referred for array comparative genomic hybridization testing, we identified three individuals—two of whom had CDH—with deletions involving a ~2.3 Mb region on chromosome 15q25.2. Two additional patients with deletions of this region have been reported, including a fetus with CDH. Clinical data from these patients suggest that recurrent deletions of 15q25.2 are associated with an increased risk of developing CDH, cognitive deficits, cryptorchidism, short stature, and possibly Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA). Although no known CDH-associated genes are located on 15q25.2, four genes in this region—CPEB1, AP3B2, HOMER2 and HDGFRP3—have been implicated in CNS development/function and may contribute to the cognitive deficits seen in deletion patients. Deletions of RPS17 may also predispose individuals with 15q25.2 deletions to DBA and associated anomalies.

Conclusions

Individuals with recurrent deletions of 15q25.2 are at increased risk for CDH and other birth defects. A high index of suspicion should exist for the development of cognitive defects, anemia, and DBA-associated malignancies in these individuals.

Keywords: congenital diaphragmatic hernia, microdeletion, 15q25.2, Diamond-Blackfan anemia, RPS17

INTRODUCTION

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH; OMIM #142340) is a structural birth defect consisting of an opening or defect in the diaphragm that originates in utero. Major, non-hernia related anomalies of the cardiovascular, central nervous, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal systems are seen in ~30–40% of patients with CDH.[1] Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) has proven to be a useful tool in identifying genomic disorders that cause non-isolated CDH (CDH+).[2] In some cases, the identification of a genomic disorder in a patient with CDH+ can improve medical care by helping clinicians create individualized diagnostic, therapeutic, and surveillance plans based on the patient’s molecular diagnosis. Data from CDH+ patients with genomic disorders can also be used to map and identifying genes that play a critical role in the development of the diaphragm and other organ systems.[2]

Chromosome 15q25.2 has been predicted to be a hotspot for genomic rearrangements based on the presence of several low copy repeats (LCRs) which can mediate non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR).[3] Here we present the clinical and molecular characteristics of three patients with 15q25.2 deletions and two patients with 15q25.2 duplications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Array comparative genomic hybridization

We reviewed the results of a cohort of over 12,000 cases referred to the Medical Genetics Laboratories at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) for aCGH testing. This cohort contained 20 patients whose indication for testing included CDH. Patients with 15q25.2 deletions or duplications were screened using Chromosome Microarray Analysis (CMA) versions 6.0–8.0 Oligo (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). After obtaining informed consent, high resolution aCGH was performed on patients with 15q25.2 deletions using either a Human Genome CGH 244K Oligo Microarray Kit G4411B (Patients 1 and 3, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) or a 1M Oligo Microarray Kit G4447A (Patient 2, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Arrays used in this study are detailed in Supplemental Table 1.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

15q25.2 and RPS17 copy numbers were determined using quantitative real-time PCR analysis as previously described.[4] Primer sequences and descriptions are provided in Supplemental Table 2.

RESULTS

Patients with 15q25.2 deletions

Microdeletions of 15q25.2 were identified in a 13-year-old boy (Patient 1) and a 1-month-old male neonate (Patient 2) with CDH+ and a 16-month-old male infant (Patient 3) without CDH. Deletions were confirmed by FISH or quantitative PCR and were not identified in available parental samples (both parents of Patients 1 and 3 and the mother of Patient 2) or in normal controls described in the Database of Genomic Variants (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/).

A literature review revealed two additional patients with similar 15q25 microdeletions; a fetus with CDH and mild hydrocephalus described by Mefford et al., and an 11-year-old girl with mild mental/psychomotor retardation described by Wagenstaller et al.[5, 6] The latter patient developed a severe hypoproliferative macrocytic anemia which started at one year of age and required blood transfusions until age four, prompting physicians to consider a diagnosis of Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA, OMIM #105650).

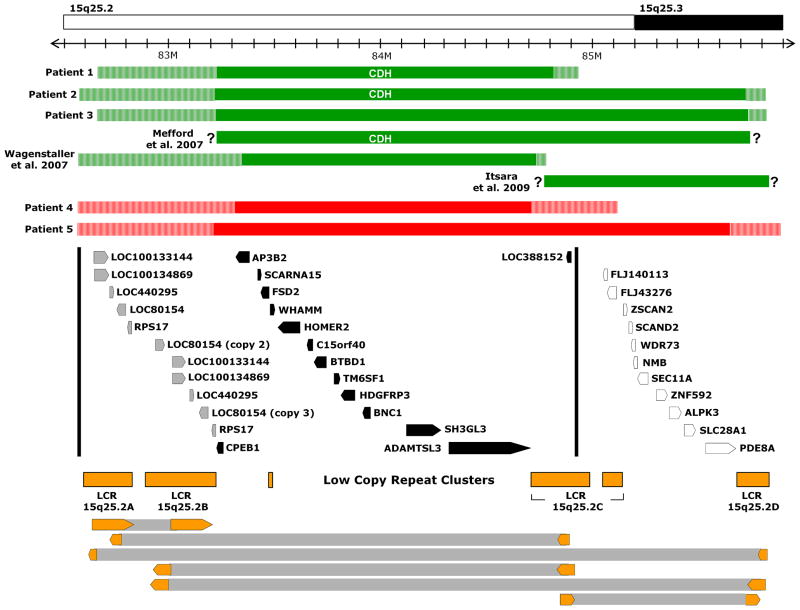

Additional clinical features and the molecular breakpoints of all five 15q25.2 deletions patients are summarized in Table 1 and depicted in Figure 1. Some features—particularly the short stature and cognitive defects seen in Patient 1—may represent the long-term effects of CDH or a combination of these secondary effects and genetic factors.

Table 1.

Clinical features and molecular breakpoints of patients with 15q25.2 microdeletions

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Mefford et al. [5] | Wagenstaller et al. [6] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 13 years | 1 month | 16 months | Fetus | 11 years |

| Gender | M | M | M | Not reported | F |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Filipino & Caucasian | Caucasian | Hispanic | Not reported | Not reported |

| CDH | Left-sided posterolateral CDH repaired on day of life 5 | Left-sided diaphragm agenesis with entire anterior, lateral and 90% of posterior aspect of chest without diaphragm, repaired on day of life 6 with a 5cm × 5cm patch | None | CDH, type not specified | None |

| CNS Studies | No imaging studies obtained | Small corpus callosum and underdeveloped gyri by head ultrasound | Brain MRI and EEG obtained for cyanotic spells at 3 months of age were normal. | Mild hydrocephalus | No imaging studies reported |

| Development/cognitive status | Early development within normal range (sitting 7–8 mo, crawling 8–9 mo, walking 14 mo, first words before age 1). Now has global developmental delay with delays in speech, motor, cognitive, social development. Various neuropsychiatric diagnoses have been considered. | Still hospitalized | Development reported to be normal. | Not applicable | Mild mental and psychomotor retardation |

| Craniofacial/neck | None | Short neck with webbing | Cleft palate, low set and posteriorly rotated ears, flat occiput, synophrys, thin vermillion, short neck with webbing | None reported | None reported |

| Cardiac | None | Small-to-moderate apical muscular VSD and two tiny posterior muscular VSDs | Coronary artery fistula, mildly dilated LV | None reported | None reported |

| Anemia | None | Two blood transfusions but anemia likely related to hospital course | Anemia which resolved on iron supplementation | None reported | Hypoproliferative, macrocytic anemia requiring blood transfusions |

| Genitourinary | Unilateral cryptorchidism | Bilateral cryptorchidism, normal renal ultrasound | Left pelvicaliectasis, mild right pelvicaliectasis (VCUG normal) | None reported | None reported |

| Other physical features | Thin body habitus, pectus excavatum, prominent medial malleoli | Bilateral inguinal hernias containing small bowel, low set nipples | Hypoplastic right thenar area, broad chest | None reported | Slight dysmorphic features, polysplenia, portal vein stenosis |

| Gestational age at birth | 36 weeks | 39 weeks | 37 weeks | Not applicable | 38 weeks |

| Birth height, weight, FOC | Weight 2.81kg (70th percentile) | Weight 3.34kg (35th percentile), Length 49 cm (35th percentile), Head circumference 34.5 cm (25th percentile) | Weight 3.07 kg (75th percentile), Length 47 cm (70th percentile) | Not applicable | Intrauterine growth retardation; Weight 1950g (<1st percentile), Length l42 cm (<1st percentile) |

| Most recent documented height and weight | At age 13, height 142.2 cm (1st percentile), weight 27.3 kg (<1st percentile) | See above | At 7 months, height 65.5cm (5th percentile), weight 7.8kg (18th percentile) | Not applicable | Short stature |

| Minimal deletion | 83,214,012–84,812,634* (~1.6 Mb) | 83,214,012–85,721,698* (~2.5 Mb) | 83,214,012–85,728,794* (~2.5 Mb) | 83,214,645–85,739,696a (~2.5 Mb) | 83,346,998–84,729,389a (~1.4 Mb) |

| Maximal deletion | 82,664,440–84,928,631 (~2.3 Mb) | 82,577,992–85,815,602 (~3.2 Mb) | 82,664,440–85,815,602 (~3.2 Mb) | Not reported | 82,573,833–84,779,738b (~2.2 Mb) |

| Inheritance | De novo | No deletion in maternal sample, paternal sample not available | De novo | Not reported | De novo |

LV = left ventricle; VSD = ventricular septal defect; VCUG = voiding cystourethrogram; N/A = not applicable

Patients 1–3 were from non-consanguineous parents, not reported for patients in Mefford et al. [5] and Wagenstaller et al. [6]

Minimal and maximal deletions reported in hg19 genomic build coordinates.

= Presumed minimal deletion;

= Based on the assumption that adjacent probes were not deleted

= qPCR data suggest that the minimal deletion may extend further to include the centromeric copy of RPS17.

Figure 1.

Deletions and duplications of chromosome 15q25. The 15q25 region based on hg19 is pictured. The minimum deleted (green) and duplicated (red) regions for each patient are shown in solid bars with the maximal deleted and duplicated regions shown in stripes. Deletions reported by Mefford et al. [5], Wagenstaller et al. [6], and Itsara et al. [9] are also represented. Genes responsible for the features associated with 15q25.2 deletions are likely to be contained within a region delineated by dark vertical lines which is based on the maximal deletions of patient described by Wagenstaller et al. (telomeric) and Patient 1 (centromeric). Genes located in this region are represented by black arrows (single copy genes) and grey arrows (genes present in more than one copy) while those outside this region are shown as outlines. Low copy repeats LCR 15q25.2A-D are depicted in orange. Pairs of large, directly oriented stretches of DNA with >98% sequence identity which could mediate non-allelic homologous recombination between LCR clusters are shown at the bottom of the figure as block arrows connected by grey bars.

Structural birth defects seen in more than one deletion patient include CDH in three patients (60%), cryptorchidism in two out of three males (66%), and cardiovascular anomalies in two patients (40%)—multiple VSDs in Patient 2 and a coronary artery fistula in Patient 3. Short stature was also documented in three out of five patients (60%) with Patient 1’s height being at the 1st percentile and Patient 3’s length at the 5th percentile.

Although Patient 1’s early development was reported to be within the normal range, significant cognitive delays were noted on standardized tests starting at age five (Supplemental Table 3). At six years of age he developed throat clearing/vocal tics and, over time, neuropsychiatric evaluations prompted a number of diagnoses including mental retardation, autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and sensory integration dysfunction. Patient 2 remains hospitalized and is too young to be thoroughly evaluated, but a head ultrasound revealed a small corpus callosum and underdeveloped gyri.

Patients with 15q25.2 duplications

Two cases involving reciprocal duplication of the 15q25.2 region were identified in our cohort (Patients 4 and 5; Figure 1; Supplemental Table 4). Patient 4 was referred for hypertension, obesity and developmental delay and was found to also have an interstitial deletion of chromosome 22q11.2 consistent with a diagnosis of velocardiofacial/DiGeorge syndrome (OMIM #192430, #188400). Patient 5 was referred for aCGH analysis for an atrial septal defect, cataracts (maternally inherited), blue sclerae, short neck with redundant skin, a shawl scrotum, and joint hypermobility. His 15q25 duplication was found to have been inherited from his asymptomatic father. No similar duplications have been reported in the Database of Genomic Variants.

Analysis of low copy repeats

A detailed analysis of the 15q25 region revealed four major LCRs (LCR 15q25.2A-D) that share large (~42 to 200 kb) directly oriented stretches of DNA with greater than 98% sequence identity (Figure 1). These findings suggest that genomic alterations identified in our patients were mediated by NAHR.[3]

RPS17 copy number in 15q25.2 deletion patients

Mutations in RPS17–which is present in two copies on 15q25.2 (Figure 1)—have been implicated in the development of DBA.[7, 8] To determine if reductions in RPS17 copy number may have contributed to the phenotype of our deletion patients, we performed quantitative real-time PCR for RPS17. Patients 1–3 were found to have a 50% reduction in RPS17 copy number when compared to normal Caucasian and Hispanic controls (Supplemental Figure 2). This result suggests that the deletion in Patients 1–3 may have resulted from a recombination event between LCR 15q25.2A and LCR 15q25.2C causing both copies of RPS17 to be deleted on the affected chromosome.

DISCUSSION

Phenotypes associated with 15q25.2 deletions and duplications

Clinical geneticists are often called upon to provide prognostic information to families and to counsel with other physicians regarding patient care plans based on molecular data obtained by aCGH analyses. Clinical data from Patients 1–3 and two previously described individuals with 15q25.2 deletions suggest that this genomic disorder places individuals at increased risk of developing CDH, cognitive deficits, cryptorchidism, short stature, and possibly Diamond-Blackfan anemia. These features are most likely caused by disruption of one or more genes located between LCR 15q25.2A and LCR 15q25.2C (Figure 1; Supplemental Table 5).

While deletions of this region may predispose individuals to the development of neuropsychiatric problems—as seen in Patient 1—the risk is likely higher for individuals with deletions that also include the region between LCR 15q25.2C and LCR 15q25.2D—including Patient 2 and 3—since deletions of this adjacent region have been identified in two patients with autism and two patients with schizophrenia (Figure 1).[9]

Although reciprocal duplications of 15q25 were identified in two patients, one carried a 22q11.2 deletion—which, alone, could account for his developmental delay—and the second inherited his duplication from his unaffected father. This suggests that if 15q25 duplications have an associated phenotype, it is likely to be either subclinical or incompletely penetrant.

The CDH minimal deleted region on Chromosome 15q25.2

The CDH minimal deleted region on 15q25.2 is defined by the maximal deletion of Patient 1. Since the diaphragm is a muscular organ, it is possible that disruption of the BTB (POZ) domain containing 1 (BTBD1) gene, which is essential for myoblast growth and differentiation in vitro, could play a role in development of CDH.[10] However, studies in rodent models suggest that some types of CDH arise from defects in the non-muscular mesenchymal substratum onto which myogenic cells and axons destined to form the neuromuscular component of the diaphragm expand.[11] Further studies have shown that development of posterolateral CDH can be associated with decreased cell proliferation leading to abnormal development of the pleuroperitoneal fold (PPF)—a triangular-shaped embryonic structure which represents the primordial diaphragm.[12] This suggests that 15q25.2 genes known to affect cell proliferation—such as hepatoma-derived growth factor, related protein 3 (HDGFRP3) and basonuclin 1 (BNC1; OMIM #601930)—may play a role in CDH development.[13, 14]

Cognitive defects and associated candidate genes

Several genes located on 15q25.2 may contribute to the cognitive delays seen in 15q25.2 deletions. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein 1 (CPEB1; OMIM #607342) has been found at postsynaptic sites of hippocampal neurons and Cpeb1−/− mice have abnormal long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) and show an impaired ability to extinguish hippocampal-dependent memories.[15, 16] Adaptor-related protein complex 3, beta-2 subunit (AP3B2; OMIM #602166) is part of a neuron-specific heterotetrameric vesicle-coat protein complex which is thought to play an important role in neurotransmitter release.[17] However, it is unlikely that deletion of either of these genes is solely responsible for the cognitive deficits seen in 15q25 deletion patients since at least one loss of AP3B2 and at least six losses of CPEB1 have been reported among normal controls in the Database of Genomic Variants (Supplemental Table 6).

In contrast, deletions of the homolog of Drosophila homer 2 gene (HOMER2; OMIM #604799) and the hepatoma-derived growth factor, related protein 3 gene (HDGFRP3) have not been described in normal controls. HOMER2 is a scaffolding protein that plays an important role in maintaining plasticity at glutamatergic synapses. Studies of Homer2−/− mice revealed an important role for this protein in modulating responses to addictive substances including alcohol and cocaine.[18] HDGFRP3 is strongly expressed in the developing nervous system and has recently been shown to modulate the neuronal cytoskeleton and to be necessary for proper neurite outgrowth in primary cortical neurons.[19]

Deletions of RPS17 and Diamond-Blackfan anemia

The ribosomal protein S17 gene (RPS17, OMIM #180472) is present in two copies on 15q25.2 and most individuals are expected to carry four alleles. De novo RPS17 mutations have been described in two patients with DBA: an otherwise healthy 4 month old male with a 2-bp deletion (200delGA) in exon 3 of RPS17—causing a frame shift and premature termination at codon 86—and a 31-year old man with severe anemia, a flat thenar eminence, facial dysmorphisms, and short stature (<3rd percentile) with single base pair substitution affecting the translation initiation start codon of RPS17.[7, 8] These mutations would argue that loss of a single copy of RPS17 can cause DBA. However, deletions of one copy of RPS17 have also been reported in at least seven normal control individuals in the Database of Genomic Variants (Supplemental Table 6). Possible explanations for these seemingly contradictory observations include: 1) the de novo RPS17 mutations may result in gain of function/dominant negative alleles, 2) the DBA patients with de novo RPS17 mutations may also have undetected sequence changes/deletions affecting other copies of RPS17 or other DBA-related genes, or 3) DBA caused by abnormalities in RPS17 may shows incomplete penetrance with the risk of developing DBA being directly related to the number of RPS17 alleles affected.

When considering whether a 50% reduction in RPS17 copy number may have adversely affected Patients 1–3, it is important to note that the clinical spectrum of DBA can include individuals without anemia who have DBA-associated congenital anomalies that commonly affect the head, facial features, eyes, palate, upper limbs/hands/thumbs, heart, and the urogenital system.[20] Although causality can not clearly be established, it is possible that changes in RPS17 copy number may have played a role in the development of the short neck and VSDs seen in Patient 2 and the cleft palate, low set ears, short neck, and hypoplastic thenar eminence seen in Patient 3. The presence of these features suggests that a high index of suspicion should exist for the development of anemia and DBA-associated malignancies in patients with 15q25.2 deletions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the families who participated in this study. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants KO8HD-050583 (to D.A.S.) and 3T32GM007330-33S1 (to M.J.W.) and grant R13-0005-04/2008 (to P.S.) from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Footnotes

LICENCE FOR PUBLICATION

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Journal of Medical Genetics and any other BMJPGL products and sublicences such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://group.bmj.com/products/journals/instructions-for-authors/licence-forms).

COMPETING INTEREST

None declared.

References

- 1.Pober BR. Overview of epidemiology, genetics, birth defects, and chromosome abnormalities associated with CDH. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2007;145C:158–171. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holder AM, Klaassens M, Tibboel D, de Klein A, Lee B, Scott DA. Genetic factors in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:825–845. doi: 10.1086/513442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mefford HC, Eichler EE. Duplication hotspots, rare genomic disorders, and common disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott DA, Klaassens M, Holder AM, Lally KP, Fernandes CJ, Galjaard RJ, Tibboel D, de Klein A, Lee B. Genome-wide oligonucleotide-based array comparative genome hybridization analysis of non-isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:424–430. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mefford HC, Clauin S, Sharp AJ, Moller RS, Ullmann R, Kapur R, Pinkel D, Cooper GM, Ventura M, Ropers HH, Tommerup N, Eichler EE, Bellanne-Chantelot C. Recurrent reciprocal genomic rearrangements of 17q12 are associated with renal disease, diabetes, and epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1057–1069. doi: 10.1086/522591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagenstaller J, Spranger S, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Kazmierczak B, Nathrath M, Wahl D, Heye B, Glaser D, Liebscher V, Meitinger T, Strom TM. Copy-number variations measured by single-nucleotide-polymorphism oligonucleotide arrays in patients with mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:768–779. doi: 10.1086/521274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gazda HT, Sheen MR, Vlachos A, Choesmel V, O’Donohue MF, Schneider H, Darras N, Hasman C, Sieff CA, Newburger PE, Ball SE, Niewiadomska E, Matysiak M, Zaucha JM, Glader B, Niemeyer C, Meerpohl JJ, Atsidaftos E, Lipton JM, Gleizes PE, Beggs AH. Ribosomal protein L5 and L11 mutations are associated with cleft palate and abnormal thumbs in Diamond-Blackfan anemia patients. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:769–780. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cmejla R, Cmejlova J, Handrkova H, Petrak J, Pospisilova D. Ribosomal protein S17 gene (RPS17) is mutated in Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:1178–1182. doi: 10.1002/humu.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itsara A, Cooper GM, Baker C, Girirajan S, Li J, Absher D, Krauss RM, Myers RM, Ridker PM, Chasman DI, Mefford H, Ying P, Nickerson DA, Eichler EE. Population analysis of large copy number variants and hotspots of human genetic disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pisani DF, Coldefy AS, Elabd C, Cabane C, Salles J, Le Cunff M, Derijard B, Amri EZ, Dani C, Leger JJ, Dechesne CA. Involvement of BTBD1 in mesenchymal differentiation. Exp Cell Res 2007. 2007;313:2417–2426. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babiuk RP, Greer JJ. Diaphragm defects occur in a CDH hernia model independently of myogenesis and lung formation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002. 2002;283:L1310–1314. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00257.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clugston RD, Zhang W, Greer JJ. Early development of the primordial mammalian diaphragm and cellular mechanisms of nitrofen-induced congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009 Aug 26;2009 doi: 10.1002/bdra.20613. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikegame K, Yamamoto M, Kishima Y, Enomoto H, Yoshida K, Suemura M, Kishimoto T, Nakamura H. A new member of a hepatoma-derived growth factor gene family can translocate to the nucleus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;266:81–87. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tseng H. Basonuclin, a zinc finger protein associated with epithelial expansion and proliferation. Front Biosci. 1998;3:D985–D988. doi: 10.2741/a338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alarcon JM, Hodgman R, Theis M, Huang YS, Kandel ER, Richter JD. (2004) Selective modulation of some forms of schaffer collateral-CA1 synaptic plasticity in mice with a disruption of the CPEB-1 gene. Learn Mem. 2004;11:318–327. doi: 10.1101/lm.72704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berger-Sweeney J, Zearfoss NR, Richter JD. Reduced extinction of hippocampal-dependent memories in CPEB knockout mice. Learn Mem. 2006;13:4–7. doi: 10.1101/lm.73706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabner CP, Price SD, Lysakowski A, Cahill AL, Fox AP. Regulation of large dense-core vesicle volume and neurotransmitter content mediated by adaptor protein 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10035–10040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509844103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szumlinski KK, Ary AW, Lominac KD, Klugmann M, Kippin TE. Accumbens Homer2 overexpression facilitates alcohol-induced neuroplasticity in C57BL/6J mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1365–1378. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Tahir HM, Abouzied MM, Gallitzendoerfer R, Gieselmann V, Franken S. Hepatoma-derived growth factor-related protein-3 interacts with microtubules and promotes neurite outgrowth in mouse cortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11637–11651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901101200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vlachos A, Ball S, Dahl N, Alter BP, Sheth S, Ramenghi U, Meerpohl J, Karlsson S, Liu JM, Leblanc T, Paley C, Kang EM, Leder EJ, Atsidaftos E, Shimamura A, Bessler M, Glader B, Lipton JM. Participants of Sixth Annual Daniella Maria Arturi International Consensus Conference. Diagnosing and treating Diamond Blackfan anaemia: results of an international clinical consensus conference. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:859–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.