Abstract

The treatment of HIV infection has dramatically reduced the incidence of AIDS-related illnesses. At the same time, non-AIDS-related illnesses such as cardiovascular and bone disease are becoming more prevalent in this population. The mechanisms of these illnesses are complex and are related in part to the HIV virus, antiretroviral medications prescribed for HIV infection, traditional risk factors exacerbated by HIV, and lifestyle and nutritional factors. Further prospective research is needed to clarify the mechanisms by which HIV, antiretroviral medications, and nutritional abnormalities contribute to bone and cardiovascular disease in the HIV population. Increasingly, it is being recognized that optimizing the treatment of HIV infection to improve immune function and reduce viral load may also benefit the development of non-AIDS-related illnesses such as cardiovascular and bone disease.

INTRODUCTION

In developed countries, people with HIV are living longer. AIDS-related illnesses are no longer a common cause of death; instead, a larger percentage of deaths are represented by non-AIDS illnesses, including liver disease, CVD5, and non-AIDS malignancies. This review resulted from a presentation given at the recent NIH and WHO Conference on Nutrition and HIV in Washington, DC (1), and focuses on data presented at that meeting, including nutritional correlates of critical diseases such as CVD and bone disease, which are seen disproportionately among HIV-infected patients in the modern era of HAART.

Treatment of HIV-infected patients has dramatically reduced deaths and morbidity from AIDS. Nonetheless, metabolic complications including cardiovascular and bone disease are seen with increasing frequency among HIV-infected patients. The cause of cardiovascular and bone disease in HIV infection is multifactorial and likely involves complex interactions between HIV infection, traditional risk factors for both diseases exacerbated by HIV, use of ART, and lifestyle factors such as tobacco use and dietary intake. Highlighting the importance of nutritional and metabolic issues in HIV, the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (DAD) study group recently showed that between 1998 and 2008 the relative increase in deaths due to CVD as a percentage of all deaths among patients with AIDS was ∼10% (2). The DAD data suggest that although deaths due to AIDS, liver disease, and non-AIDS malignancies decreased between 1999/2000 and 2007/2008 the number of deaths from CVD remained relatively stable and thus represents a larger percentage of deaths among patients in the modern era of HAART (2). With regard to bone disease, in a recent meta-analysis of 884 HIV-infected patients compared with 654 non-HIV-infected patients, 67% of HIV-infected patients had decreased BMD. The relative risk was 3.8 (95% CI: 2.3, 5.8) for osteoporosis and 6.7 (95% CI: 3.7, 11.3) for osteopenia (3).

HIV INFECTION AND CVD

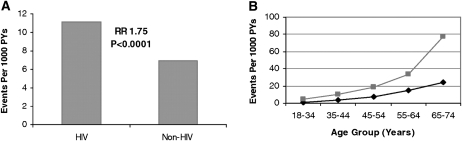

Large epidemiologic studies with comparisons between HIV- and non-HIV-infected patients have shown a significant increase in AMI rates among HIV-infected patients. In a health care registry study, Triant et al (4) observed a 1.75-fold increased relative risk of myocardial infarction in HIV- compared with non-HIV-infected patients (Figure 1). This increase was seen across all age strata, but the relative risk increased with age. Although the increased relative risk was greater among HIV-infected women compared with non-HIV-infected women, the risk was significant in both sexes. In another health care registry study, Klein et al (5) showed that congestive heart disease and myocardial infarction were higher in HIV patients than in non-HIV patients.

FIGURE 1.

A: Myocardial infarction rates and corresponding adjusted RRs. Bars indicate crude rates of acute myocardial infarction events per 1000 PY , as determined by ICD coding. RRs and associated P values are shown above the bars. RR was determined from Poisson regression analysis with adjustment for age, sex, race, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. Associated 95% CIs for the RRs shown are 1.51–2.02. B: Myocardial infarction rates by age group. The light line indicates patients who received a diagnosis of HIV disease. The dark line indicates patients who did not receive a diagnosis of HIV disease. Data shown include both sexes. Rates represent the number of events per 1000 PY, as determined by ICD coding. ICD, International Classification of Diseases; PY, person-years. Reproduced with permission from reference 4.

The increased prevalence of CVD in HIV patients is multifactorial; immune dysfunction, toxicities of some antiretroviral drugs, and metabolic factors all contribute to the increase in CVD rates in this population. Triant et al (4) observed that traditional risk factors, including dyslipidemia (23.3% compared with 17.6%), hypertension (21.2% compared with 15.9%), and diabetes (11.5% compared with 6.6%) were all increased in HIV relative to the non-HIV-infected patients (P < 0.0001 for each comparison). These traditional risk factors accounted for 25% of the increased cardiac risk, which shows the importance of metabolic abnormalities as contributing risk factors to increased cardiac disease rates in HIV-infected patients. A relative increase in diabetes incidence was observed in a carefully performed study in which HIV and non-HIV patients in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) were compared. When age and BMI (in kg/m2) were controlled for, the diabetes incidence was 4.7 cases compared with 1.4 cases per 100 person-years, for an incidence rate ratio 4.11 in HIV compared with non-HIV patients (6). However, recent studies have shown that CVD rates remain increased among HIV-infected patients when traditional metabolic risk factors are controlled for (4).

Lifestyle factors such as tobacco use and dietary habits may also contribute to CVD in the HIV-infected population. Smoking is highly prevalent in HIV-infected patients, and studies suggest smoking rates of 40–69% (7–9). The DAD study group recently showed that CVD events decreased with increased duration in time since smoking cessation (7). Joy et al (10) examined dietary intake among 356 HIV-infected patients and 162 non-HIV-infected patients and reported that the HIV-infected patients in this study had a significantly increased dietary intake of total fat, saturated fat, dietary cholesterol, and trans fat compared with the non-HIV patients. Notably, saturated fat intake was strongly associated with triglyceride concentration in this study.

In addition to traditional risk factors, antiretroviral drugs may contribute to CVD in HIV-infected patients. For each year of HAART use, the relative risk of AMI increased 16%, and PIs as a class, but not NRTIs, have been associated with increased AMI rates (11). Of note, inclusion of dyslipidemia in this analysis attenuated the relation between PI use and AMI from 1.16 to 1.10, which suggests that PIs may increase myocardial infarction rates in part through deleterious effects on lipids.

Recently, attention has focused on specific antiretroviral drugs as potential contributors to increased AMI rates. Data from the DAD study suggest that the recent use of the NRTI abacavir is associated with an increased risk of AMI (12). Activation of inflammatory and hemostatic pathways may explain the short-term risk of abacavir use, which is not seen with longer-term use and is diminished after abacavir discontinuation. Several potential mechanisms have been reported to explain abacavir-related CVD and they include platelet hyperreactivity (13), endothelial dysfunction (14), elevated CRP (15), and IL6 (16).

Recent data suggest that, in addition to traditional CVD risk factors and antiretroviral use, body-composition abnormalities, including increased visceral adiposity and reduced subcutaneous fat, may be associated with a metabolic risk that increases AMI risk. Shlay et al (17) showed relative increases in visceral and truncal adiposity in HIV-infected antiretroviral-naive patients who initiated therapy. At the same time, subcutaneous and extremity fat are reduced, and thus patients experience a relative fat redistribution toward increased central adiposity. Hadigan et al (18) showed increased rates of impaired glucose tolerance, as well as diabetes and dyslipidemia, in patients with increased central fat accumulation. Similarly, increased visceral and upper trunk fat was highly predictive of insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in the Fat Redistribution and Metabolic Change in HIV Infection (FRAM) study (19) and of reduced glucose disposal in euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp studies (20). In addition, reduced extremity fat itself may contribute to these metabolic abnormalities and increased CVD rates (19, 21). Recently, Guaraldi et al (22) has shown that when cholesterol concentrations, smoking, years of ART exposure, and age are controlled for, increased visceral fat is associated with increased coronary calcifications.

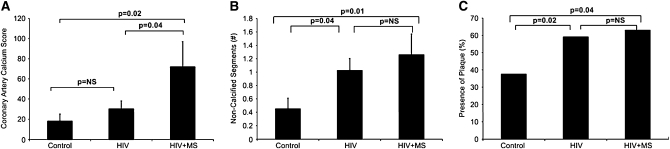

Recent data from coronary computed tomography angiography have shown that subclinical coronary disease is prevalent, even among HIV-infected patients without a significant history of CVD and without significant coronary risk factors. With the use of coronary computed tomography angiography, Lo et al (23) compared HIV and non-HIV-infected patients, matched on traditional cardiac risk factors and smoking. The presence of coronary plaque (59% compared with 34%, P = 0.02), segments with plaque [1 (0–3) compared with 0 (0–1) segments, P = 0.03], and plaque volume 55.9 (0–207.7) compared with 0 (0–80.5) μL, P = 0.02 median (interquartile range)] were all significantly increased among HIV-infected patients compared with carefully matched non-HIV-infected patients. Alarmingly, 6.5% of the HIV patients compared with none of the non-HIV patients showed critical stenosis. In the HIV patients, traditional risk factors, including age, Framingham Risk Score, and LDL were all highly associated with increased plaque. Nontraditional risk factors, including duration of HIV, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, and CD4/CD8 ratio were also associated with increased plaque. The duration of HIV remained significantly associated with plaque when age and traditional risk factors were controlled for. Data from Fitch et al (24) provide further insight into the contribution of traditional and nontraditional risk factors to increased CVD in HIV-infected patients. In this study HIV-infected patients with National Cholesterol Educational Program-ATP III–defined metabolic syndrome were shown to have higher coronary artery calcification scores compared with HIV-infected patients without metabolic syndrome and non-HIV control subjects, whereas each group of HIV-infected patients in this study had an elevated number of noncalcified plaque segments compared with control subjects (Figure 2). Noncalcified plaque segments are recognized as being more prone to rupture than are calcified lesions, which are considered more stable. Fitch et al (24) established traditional risk factors as contributors to a specific type of cardiac lesion with increased calcium, whereas HIV itself may contribute to increased noncalcified lesions, which may be more at risk of abrupt rupture.

FIGURE 2.

Markers of cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients. A: The mean (±SEM) coronary artery calcium scores were 18 ± 7 in control participants, 30 ± 8 in HIV patients, and 72 ± 25 in HIV patients with MS (P = 0.02, ANOVA). B: The mean (±SEM) numbers of noncalcified segments were 0.45 ± 0.16 in control participants, 1.02 ± 0.18 in HIV patients, and 1.26 ± 0.31 in HIV patients with MS (P = 0.05, ANOVA). C: The prevalence of plaque was 38% in control participants, 59% in HIV patients, and 63% in HIV patients with MS (P = 0.05, ANOVA). MS, metabolic syndrome. Reproduced with permission from reference 24.

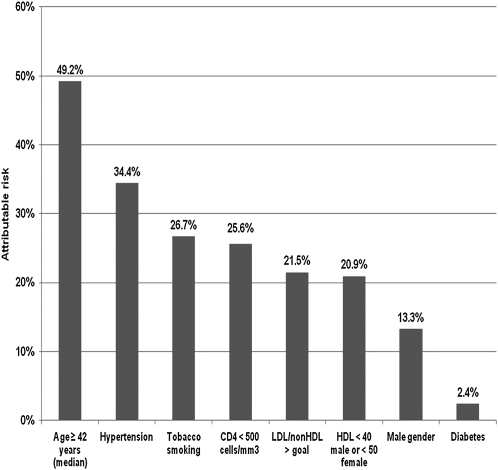

The importance of immune dysfunction as a risk factor for CVD in HIV has been further corroborated by 2 recent studies. Lichtenstein et al (25) showed that a CD4 count <500 cells/mm3 was associated with a higher OR of a combined cardiovascular end point (Figure 3). Similarly, Triant et al (26) observed a 2-fold increased AMI rate in HIV patients with CD4 <200 cell/mm3, when ART use and traditional cardiovascular risk factors were controlled for. The hypothesis that immune dysfunction and related inflammation contribute to increased CVD was further buttressed by results from the Strategies for the Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) study, in which it was shown that randomization to drug conservation and minimized ART use was associated with more CVD than randomization to the viral suppression group with more continuous ART use. The result of the SMART trial was contrary to the previously hypothesized theory that increased ART exposure, through effects on metabolic variables, may increase CVD (27).

FIGURE 3.

Attributable risk of factors associated with incident cardiovascular disease events. The HIV Outpatient Study, January 2002 to September 2009 (n = 2005). Reproduced with permission from reference 25.

Taken together, the data available to date suggest that there are important nutritional and metabolic correlates of increased CVD in HIV-infected patients, and that these metabolic abnormalities, including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and increased visceral adiposity, may contribute to increased CVD in this population. Traditional risk factors may contribute to the development of lesions that are calcified and thought to be stable, whereas inflammation and immune dysfunction caused by HIV, and more frequently related to a less-well-controlled virus, may contribute to noncalcified plaque, which may pose a greater risk of plaque rupture.

Given the potential role that inflammation may play in CVD in HIV-infected patients, a critical question is whether increased CRP is associated with increased AMI rates. In a large health care data registry study, Triant et al (26) showed that CRP rates were increased in HIV-infected patients (68% compared with 48%, P < 0.0001). Increased CRP was associated with a 2-fold increased risk of AMI in HIV-infected patients, when age, race, and traditional risk factors including dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus were controlled for. Patients with HIV and increased CRP were at a 4-fold increased risk of AMI. Recently, data from the FRAM study (28) suggested that increased CRP is independently associated with increased mortality in HIV patients.

Increased AMI rates suggest the importance of screening for cardiac disease in HIV-infected patients. Specific prediction equations are being developed for use in the HIV population. In addition, recent studies have investigated whether traditional equations used in non-HIV patients may be of use in the HIV population. With the use of data from the DAD study, Law et al (29) showed that the Framingham equation generally does well in the HIV population but may underpredict rates in HAART-treated patients and smokers and overpredict events in non-HAART-treated patients. Recent data also suggest that both traditional and nontraditional risk factors contribute to increased CVD in HIV-infected patents, and screening algorithms that account for metabolic and nontraditional inflammatory and immunologic dysfunction may be useful in screening for and predicting CVD in HIV patients.

A number of treatment strategies that target metabolic abnormalities in HIV-infected patients are now under investigation. Strategies to treat dyslipidemia appropriately focus most often on high triglyceride concentrations seen in the HIV population. Fibrates (30, 31), niacin (32, 33), and fish oil (34) have been investigated, with various degrees of success, to lower triglyceride concentrations. Acipimox, an inhibitor of lipolysis, has also been investigated and has been shown to simultaneously improve triglyceride and insulin sensitivity in HIV-infected patients (35). In addition, β-hydroxy-β-methylglutaryl CoA reductase inhibitors can be used if total cholesterol and LDL concentrations are increased, but interactions with specific PIs must be considered (36). Treatment of insulin resistance has focused on insulin-sensitizing agents, including metformin and glitazones. Metformin has been shown to improve fasting and 2-h glucose while it lowers insulin concentrations in HIV-infected patients with preexisting insulin resistance and increased central adiposity, a population for whom this strategy is most well adapted (37). In addition, metformin has been shown to reduce tissue-type plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-I, markers of impaired fibrinolysis associated with insulin resistance and CVD (38). However, care must be taken to avoid use in patients with liver and kidney dysfunction. Glitazones have the theoretic advantage of increasing subcutaneous fat and reducing liver fat while improving insulin resistance, but one drug in this class, rosiglitazone, has been associated recently with increased cardiovascular risk in non-HIV-infected patients (39) and may not be appropriate to reduce cardiovascular risk in insulin-resistant HIV-infected patients. In addition, glitazones are associated with weight gain and, more rarely, with fluid retention and heart failure, which makes it more difficult and inappropriate to use this class of agent, particularly in overweight HIV patients at high risk of CVD. Lifestyle modification is also an important goal for reducing cardiovascular risk in HIV-infected patients. Fitch et al (40) investigated a lifestyle intervention program modeled after the program used in the Diabetes Prevention Program, to increase activity and improve nutritional intake over 6 mo. In this randomized study, total caloric (−347 kcal/d) and saturated fat intake was reduced (−2%/d) and fiber intake increased (+4 g/d) in HIV-infected patients with the metabolic syndrome who underwent lifestyle modification. In response to the lifestyle program, systolic blood pressure, waist circumference, and glycated hemoglobin significantly improved compared with the control group. In addition to dietary patterns and physical activity, a lifestyle factor that should be addressed in HIV-infected patients is smoking cessation, which is critical to reduce risk of CVD in this population. Other strategies to reduce visceral fat and waist circumference include growth hormone–releasing hormone (41), which also improved adipokines and markers of impaired thrombolysis (42) and has been shown to improve triglycerides, cholesterol, and HDL in a pooled analysis of recent phase III studies (43). Lastly, early use of ART to reduce viral load and improve immune function, and use of an ART regimen least likely to contribute to metabolic abnormalities, is important to reduce cardiovascular risk in this population.

HIV INFECTION AND BONE DISEASE

Decreased BMD is common and represents another major comorbidity with nutritional correlates in HIV-infected patients. Similar to CVD, bone disease is multifactorial and is likely related to HIV infection and antiretroviral use, as well as traditional osteoporosis risk factors such as tobacco use and low vitamin D concentrations, which are prevalent in individuals with HIV infection. An initial study by Tebas et al (44) investigated bone density among HIV-infected patients who received a PI, those who did not receive a PI, and a control group. This study showed a significant decrease in bone density in HIV-infected men who received a PI, but the relation of low bone density to PI use remains controversial. Dolan et al (45) showed a 54% prevalence of osteopenia in HIV-infected women, with an increased relative risk of 2.6 compared with non-HIV-infected patients when age, BMI, menstrual function, and race were controlled for. Among these patients, markers of bone turnover were increased, which suggests increased bone resorption as a potential mechanism. No effect of PI use or specific ART regimen on bone loss was seen in this study. Similarly, low bone density has been shown in postmenopausal HIV-infected women compared with non-HIV-infected women, (46) and reduced bone density may pose a problem for HIV-infected women as they age and live longer with chronic HIV infection. Although the specific mechanism by which individual ARTs might decrease bone density has yet to be established, preliminary data suggest that low BMD is associated with use of the NRTI, tenofovir (47).

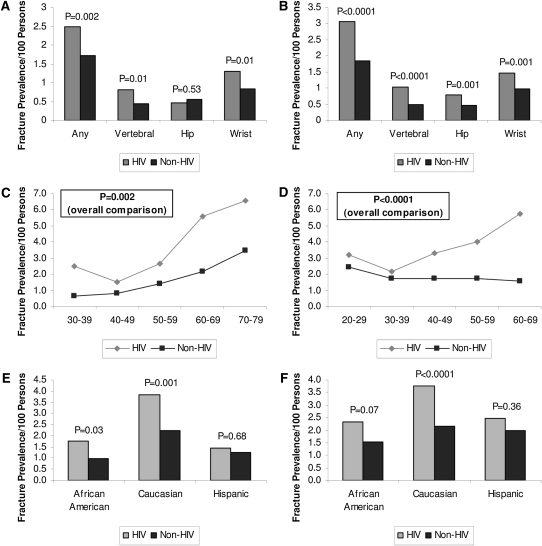

A critical question for the HIV-infected population is whether bone loss is associated with increased fracture risk in this population. A recent study by Triant et al (48) shed light on this important question (Figure 4). With the use of a population data registry of >8000 HIV-infected patients and 2,000,000 non-HIV-infected patients, the relative risk of fracture was shown to be increased in the HIV-infected group (overall prevalence: 2.87 patients with fractures per 100 persons in HIV-infected patients compared with 1.77 in non-HIV-infected patients; P < 0.0001) (48). Among women, the overall fracture prevalence was 2.49 in HIV-infected patients compared with 1.72 in non-HIV patients (P = 0.002). Among men the fracture prevalence was also higher in HIV-infected compared with non-HIV-infected patients (3.08 compared with 1.83, P < 0.0001) (48). HIV-infected women had a higher prevalence of vertebral fractures but a similar prevalence of hip fractures. HIV-infected men had a higher prevalence of vertebral and hip fractures. Among both men and women the relative differences in fracture rates appeared to increase with age, which again suggests that this comorbidity of HIV may pose the greatest problem in an aging population who live with HIV as a chronic disease.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of fracture prevalence in HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected patients by sex (left panels: women; right panels: men) and site of fracture, age group, and race. A and B: Comparison according to sex and site of fracture. C and D: Comparison according to sex and age group. E and F: Comparison according to sex and race. In C and D, the P values are for the comparison of overall fracture prevalence between HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected patients. Reproduced with permission from reference 48.

There are several metabolic and nutritional mechanisms that may contribute to bone loss in HIV disease. One intriguing possibility is that the RANKL system is activated in association with increased HIV viral load and immune dysfunction, and thus may contribute to the increased bone turnover and resorption seen in this population. In a recent study Gibellini et al (49) showed increased RANKL in HIV-infected patients with increased viral load and a highly significant association between increased RANKL and low bone density measured by DXA scan. The specific mechanisms by which increased RANKL may be activated by increased viral load are not clear, and further research is needed in this area.

Other, more traditional, mechanisms by which bone density may relate to metabolic and nutritional consideration include low weight itself, hypogonadism, vitamin D deficiency, phosphate wasting, and central fat distribution, all of which may contribute to bone loss in this population. Bone density has been shown to relate significantly to weight in numerous studies of HIV-infected patients. For example, Dolan et al (50) showed that low weight, amenorrhea, and low testosterone in HIV-infected women are all associated with bone loss. Reduced testosterone is highly prevalent in HIV-infected men and women and may also contribute to increased bone loss. In addition to weight, abnormalities in body composition may also contribute to low bone density. Huang et al (51) showed that increased central adiposity is associated with reduced bone density. The mechanism of low BMD with increased central adiposity is unclear; however, low growth hormone, which is associated with increased central adiposity, may be a contributing factor. Indeed, administration of a growth hormone–releasing hormone was shown recently to increase bone turnover, with a relatively greater effect on bone formation than bone resorption, among HIV-infected patients (52).

With regard to other traditional risk factors for low BMD, Seminari et al (53) have shown that 25 hydroxy vitamin D concentrations are reduced in HIV-infected patients. The cause of low vitamin D concentrations in this population is currently unknown; however, low vitamin D concentrations are thought to be related to ART use, in particular PIs and the NRTI, tenofovir. Cozzolino et al (54) have shown that PIs may further reduce 1-α-hydroxylation to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, whereas tenofovir may contribute to reduced glomerular filtration and to a decrease in function of α1-hydroxylase. At the same time, tenofovir may result in renal tubular dysfunction and hypophosphatemia (55).

DXA should be used to screen for bone disease in HIV-infected patients. The Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends DXA for HIV-infected patients ≥50 y of age with at least one additional risk factor for low BMD (56). Many HIV-infected patients have additional risk factors and therefore should be screened with a DXA scan according to these guidelines.

Treatment options for decreased BMD have recently been expanded for HIV-infected patients. Optimizing weight, vitamin D status and calcium intake, menstrual function, renal function, and virologic control are all rational strategies to prevent bone loss in this population. In this regard it is also important to minimize the use of drugs such as steroids that are known to contribute to low bone density in HIV-infected patients, and potentially to avoid drugs that contribute to metabolic abnormalities in phosphate and calcium handling and have effects on renal function. In hypogonadal men the use of physiologic testosterone is reasonable. Secondary causes of decreased BMD, such as vitamin D deficiency, should be screened for and appropriate treatment given.

Multiple studies of bisphosphonates have now been completed in HIV-infected patients and have shown a significant increase in bone density. McComsey et al (57) showed a 3.38% increased BMD in the lumbar spine (P < 0.001 compared with baseline) after 48 wk of treatment with alendronate. Similarly, Huang et al (58) showed increased BMD after 12 mo after a one-time infusion of zolendronate. Lumbar spine BMD increased by 3.7% in the zolendronate group compared with 0.7% in the placebo group (P = 0.04) (58). All subjects in both of these studies received 1 g calcium and 400 IU vitamin D supplements daily. No specific safety issues were observed, but the studies were small, and concern has been raised in general about the long-term safety of this class of agents. The potential risks include atypical femoral fracture (59) and osteonecrosis of the jaw (60), seen more frequently in women who received IV bisphosphonate for multiple dental procedures. However, additional data have shown increased BMD with no increase in risk of fracture in postmenopausal women on long-term alendronate (61, 62). No consensus has yet been developed about the use of these drugs in HIV-infected patients, and research is urgently needed. Until specific information is available, clinicians should use guidelines developed for the use of these agents in non-HIV-infected patients. Recent guidelines from the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommend treatment of osteoporosis for postmenopausal women and men ≥50 y with a T score of the total hip, femoral neck, or lumbar spine ≤−2.5 or in those with a history of fracture. Additionally, for those with osteopenia it is important to use the WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool to calculate the 10-y risk of both major osteoporotic fracture and hip fracture alone (63).

CONCLUSIONS

Increased cardiovascular and bone disease are important comorbidities associated with long-term HIV disease and its treatment. The specific mechanisms of these abnormalities are multifactorial, but inflammation associated with HIV infection may contribute to both increased CVD and low bone density. Multiple metabolic abnormalities, including dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and increased visceral adiposity, may contribute to increased CVD, and these may be targeted with insulin-sensitizing, lipid-lowering, and lifestyle-management programs. Optimization of ART regimen, with an eye toward minimization of CVD, is also important, but considerations of resistance and virologic control must always be paramount. In terms of bone loss, initial studies do suggest a clinical consequence of reduced bone density in the HIV population, which is reflected in an increased fracture rate. Optimization of calcium intake, vitamin D status, physical activity, ART regimen, and gonadal function are all important to improve bone density. Treatment with bisphosphonates may be useful in select cases with severe loss of bone density, but further research is needed in this regard. In addition, more research is needed into the mechanisms by which inflammation may contribute to both CVD and bone loss.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—SG: originated the project and presented the material at the NIH and WHO conference; and KF and SG: reviewed the published literature to provide the structure for the article and wrote, read, and edited the text, including references. The funding sources exercised no influence on the manuscript. SG has received research funding from Theratechnologies and Bristol Myers Squibb and served as a consultant for Theratechnologies and EMD Serono. KF had no disclosures to make.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ART, antiretroviral therapy; BMD, bone mineral density; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DAD, Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; RANKL, nuclear transcription factor κB ligand.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grinspoon S. Nutritional correlates of metabolic complications, CVD, bone, insulin sensitivity: what do we do? Nutrition in clinical management of HIV infected adolescents and adults including pregnant and lactating women: what do we know, and what can we do, and where do we go from here? Washington, DC: 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV drugs (D: A:D) Study Group, Smith C, Sabin CA, Lundgren JD, Thiebaut R, Weber R, Law M, D'Arminio Monforte A, Kirk O, Friis-Moller N, et al. Factors associated with specific causes of death amongst HIV-positive individuals in the D:A:D Study. AIDS 2010;24:1537–48 (Published erratum appears in AIDS 2011:25:883.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown TT, Qaqish RB. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS 2006;20:2165–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:2506–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein D, Hurley LB, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Sidney S. Do protease inhibitors increase the risk for coronary heart disease in patients with HIV-1 infection? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002;30:471–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown TT, Cole SR, Li X, Kingsley LA, Palella FJ, Riddler SA, Visscher BR, Margolick JB, Dobs AS. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1179–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friis-Moller N, Weber R, Reiss P, Thiebaut R, Kirk O, Monforte A, Pradier C, Morfeldt L, Mateu S, Law M, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in HIV patients–association with antiretroviral therapy. Results from the DAD study. AIDS 2003;17:1179–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vittecoq D, Escaut L, Chironi G, Teicher E, Monsuez JJ, Andrejak M, Simon A. Coronary heart disease in HIV-infected patients in the highly active antiretroviral treatment era. AIDS 2003;17(suppl 1):S70–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lifson AR, Neuhaus J, Arribas JR, van den Berg-Wolf M, Labriola AM, Read TR. Smoking-related health risks among persons with HIV in the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy clinical trial. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1896–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joy T, Keough HM, Hadigan C, Lee H, Dolan SE, Fitch KV, Liebau J, Lo J, Johnsen S, Hubbard JL, et al. Dietary fat intake and relationship to serum lipid levels among HIV-infected subjects with metabolic abnormalities in the era of HAART. AIDS 2007;21:1591–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friis-Miller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, Weber R, Monforte A, El-Sadr W, Thiebaut R, De Wit S, Kirk O, Fontas E, et al. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1723–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabin CA, Worm SW, Weber R, Reiss P, El-Sadr W, Dabis F, De Wit S, Law M, D'Arminio Monforte A, Friis-Moller N, et al. Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients enrolled in the D:A:D study: a multi-cohort collaboration. Lancet 2008;371:1417–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satchell C, O'Connor E, Peace A, Cotter A, Sheehan G, Tedesco T, Doran P, Powderly W, Kenny D, Mallon P, Platelet hyper-reactivity in HIV-1-infected patients on abacavir-containing ART. 16th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Montreal, Canada, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsue PY, Hunt PW, Schnell A, Kalapus SC, Hoh R, Ganz P, Martin JN, Deeks SG. Role of viral replication, antiretroviral therapy, and immunodeficiency in HIV-associated atherosclerosis. AIDS 2009;23:1059–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stategies for Management of Anti-Retroviral Therapy/INSIGHT: DAD Study Groups Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 2008;22:F17–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuller L, SMART Study Group Elevated levels of interleukin-6 and d-dimer are associated with an increased risk of death in patients with HIV. 15th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shlay JC, Bartsch G, Peng G, Wang J, Grunfeld C, Gilbert CL, Visnegarwala F, Raghavan SS, Xiang Y, Farrough M, et al. Long-term body composition and metabolic changes in antiretroviral naive persons randomized to protease inhibitor-, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-, or protease inhibitor plus nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based strategy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;44:506–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadigan C, Meigs JB, Corcoran C, Rietschel P, Piecuch S, Basgoz N, Davis B, Sax P, Stanley T, Wilson PW, et al. Metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular disease risk factors in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and lipodystrophy. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:130–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wohl D, Scherzer R, Heymsfield S, Simberkoff M, Sidney S, Bacchetti P, Grunfeld C. The associations of regional adipose tissue with lipid and lipoprotein levels in HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;48:44–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadigan C, Kamin D, Liebau J, Mazza S, Barrow S, Torriani M, Rubin R, Weise S, Fischman A, Grinspoon S. Depot-specific regulation of glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity in HIV-lipodystrophy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2006;290:E289–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadigan C, Meigs JB, Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Davis B, Basgoz N, Sax PE, Grinspoon S. Prediction of coronary heart disease risk in HIV-infected patients with fat redistribution. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:909–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guaraldi G, Stentarelli C, Zona S, Orlando G, Carli F, Ligabue G, Lattanzi A, Xaccherini G, Rossi R, Modena MG, et al. Lipodystrophy and anti-retroviral therapy as predictors of sub-clinical atherosclerosis in human immunodeficiency virus infected subjects. Atherosclerosis 2010;208:222–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo J, Abbara S, Shturman L, Soni A, Wei J, Rocha-Filho JA, Nasir K, Grinspoon SK. Increased prevalence of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis detected by coronary computed tomography angiography in HIV-infected men. AIDS 2010;24:243–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitch K, Lo J, Abbara S, Ghoshhajra B, Shturman L, Soni A, Sacks R, Wei J, Grinspoon S. Increased coronary artery calcium score and noncalcified plaque among HIV-infected men: relationship to metabolic syndrome and cardiac risk parameters. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55:495–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lichtenstein KA, Armon C, Buchacz K, Chmiel JS, Buckner K, Tedaldi EM, Wood K, Holmberg SK, Brooks JT. Low CD4+ T cell count is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease events in the HIV outpatient study. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:435–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Triant VA, Regan S, Lee H, Sax PE, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK. Association of immunologic and virologic factors with myocardial infarction rates in a US healthcare system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55:615–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, Gordin F, Abrams D, Arduino RC, Babiker A, Burman W, Clumeck N, Cohen CJ, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2283–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tien PC, Choi AI, Zolopa AR, Benson C, Tracy R, Scherzer R, Bacchetti P, Shlipak M, Grunfeld C. Inflammation and mortality in HIV-infected adults: analysis of the FRAM study cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55:316–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Law MG, Friis-Moller N, El-Sadr WM, Weber R, Reiss P, D'Arminio Monforte A, Thiebaut R, Morfeldt L, De Wit S, et al. The use of the Framingham equation to predict myocardial infarctions in HIV-infected patients: comparison with observed events in the D:A:D Study. HIV Med 2006;7:218–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Hurley L, Go AS, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Klein D, Horberg MA. Response to newly prescribed lipid-lowering therapy in patients with and without HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:301–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller J, Brown D, Amin J, Kent-Hughes J, Law M, Kaldor J, Cooper DA, Carr A. A randomized, double-blind study of gemfibrozil for the treatment of protease inhibitor-associated hypertriglyceridaemia. AIDS 2002;16:2195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dube MP, Wu JW, Aberg JA, Deeg MA, Alston-Smith BL, McGovern ME, Lee D, Shriver SL, Martinez AI, Greenwald M, et al. Safety and efficacy of extended-release niacin for the treatment of dyslipidaemia in patients with HIV infection: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5148. Antivir Ther 2006;11:1081–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerber MT, Mondy KE, Yarasheski KE, Drechsler H, Claxton S, Stoneman J, DeMarco D, Powderly WG, Tebas P. Niacin in HIV-infected individuals with hyperlipidemia receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:419–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wohl DA, Tien HC, Busby M, Cunningham C, MacIntosh B, Napravnik S, Danan E, Donovan K, Hossenipour M, Simpson J. Randomized study of the safety and efficacy of fish oil (omega-3 fatty acid) supplementation with dietary and exercise for counseling for the treatment of antiretroviral therapy-associated hypertriglyceridemia. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:1498–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hadigan C, Liebau J, Torriani M, Andersen R, Grinspoon S. Improved triglycerides and insulin sensitivity with 3 months of acipimox in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:4438–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fichtenbaum CJ, Gerber JG, Rosenkranz SL, Segal Y, Aberg JA, Blaschke T, Alston B, Fang F, Kosel B, Aweeka F. Pharmacokinetic interactions between protease inhibitors and statins in HIV seronegative volunteers: ACTG Study A5047. AIDS 2002;16:569–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hadigan C, Corcoran C, Basgoz N, Davis B, Sax P, Grinspoon S. Metformin in the treatment of HIV lipodystrophy syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000;284:472–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hadigan C, Meigs JB, Rabe J, D'Agostino RB, Wilson PW, Lipinska I, Tofler GH, Grinspoon S. Increased PAI-1 and tPA antigen levels are reduced with metformin therapy in HIV-infected patients with fat redistribution and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:939–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. [see comment] N Engl J Med 2007;356:2457–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fitch KV, Anderson EJ, Hubbard JL, Carpenter SJ, Waddell WR, Caliendo AM, Grinspoon SK. Effects of a lifestyle modification program in HIV-infected patients with the metabolic syndrome. AIDS 2006;20:1843–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Falutz J, Allas S, Blot K, Potvin D, Kotler D, Somero M, Berger D, Brown S, Richmond G, Fessel J, et al. Metabolic effects of a growth hormone-releasing factor in patients with HIV. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2359–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanley TL, Falutz J, Mamputu JC, Soulban G, Potvin D, Grinspoon SK. Effects of tesamorelin on inflammatory markers in HIV patients with excess abdominal fat: relationship with visceral adipose reduction. AIDS 2011;25:1281–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Falutz J, Mamputu J, Potvin D, Moyle GJ, Soulban G, Loughrey H, Marsolais C, Turner R, Grinspoon S. Effects of tesamorelin (TH9507), a growth hormone-releasing factor analog, in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with excess abdominal fat: a pooled analysis of two multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled phase 3 trials with safety extension data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:4291–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tebas P, Powderly WG, Claxton S, Marin D, Tantisiriwat W, Teitelbaum SL, Yarasheski KE. Accelerated bone mineral loss in HIV-infected patients receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2000;14:F63–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dolan SE, Huang JS, Killilea KM, Sullivan MP, Aliabadi N, Grinspoon S. Reduced bone density in HIV-infected women. AIDS 2004;18:475–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yin M, Dobkin J, Brudney K, Becker C, Zacel J, Manandhar M, Addesso V, Shane E. Bone mass and mineral metabolism in HIV+ postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:1345–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stellbrink HJ, Orkin C, Arribas JR, Compston J, Gerstoft J, Van Wijngaerden E, Lazzarin A, Rizzardini G, Sprenger HG, Lambert J, et al. Comparison of changes in bone density and turnover with abacavir-lamivudine versus tenofovir-emtricitabine in HIV-infected adults: 48-week results from the ASSERT study. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:963–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Triant VA, Brown TT, Lee H, Grinspoon SK. Fracture prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected versus non-HIV-infected patients in a large U.S. healthcare system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:3499–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gibellini D, Borderi M, De Crignis E, Cicola R, Vescini F, Caudarella R, Chiodo F, Re MC. RANKL/OPG/TRAIL plasma levels and bone mass loss evaluation in antiretroviral naive HIV-1-positive men. J Med Virol 2007;79:1446–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dolan SE, Carpenter S, Grinspoon S. Effects of weight, body composition, and testosterone on bone mineral density in HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;45:161–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang JS, Rietschel P, Hadigan CM, Rosenthal DI, Grinspoon S. Increased abdominal visceral fat is associated with reduced bone density in HIV-infected men with lipodystrophy. AIDS 2001;15:975–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mamputu J, Soulban G, Falutz J, Huong Pham M, Marsolais C, Assaad H, Grinspoon S. Effects of tesamorelin, a growth hormone-releasing factor analogue, on bone turnover markers in HIV-infected patients with excess abdominal fat. 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seminari E, Castagna A, Soldarini A, Galli L, Fusetti G, Dorigatti F, Hasson H, Danise A, Guffanti M, Lazzarin A, et al. Osteoprotegerin and bone turnover markers in heavily pretreated HIV-infected patients. HIV Med 2005;6:145–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cozzolino M, Vidal M, Arcidiacono MV, Tebas P, Yarasheski KE, Dusso AS. HIV-protease inhibitors impair vitamin D bioactivation to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. AIDS 2003;17:513–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cooper RD, Wiebe N, Smith N, Keiser P, Naicker S, Tonelli M. Systematic review and meta-analysis: renal safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:496–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aberg JA, Kaplan JE, Libman H, Emmanuel P, Anderson JR, Stone VE, Oleske JM, Currier JS, Gallant JE. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus: 2009 update by the HIV medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:651–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McComsey GA, Kendall MA, Tebas P, Swindells S, Hogg E, Alston-Smith B, Suckow C, Gopalakrishnan G, Benson C, Wohl DA. Alendronate with calcium and vitamin D supplementation is safe and effective for the treatment of decreased bone mineral density in HIV. AIDS 2007;21:2473–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang J, Meixner L, Fernandez S, McCutchan JA. A double-blinded, randomized controlled trial of zoledronate therapy for HIV-associated osteopenia and osteoporosis. AIDS 2009;23:51–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lenart BA, Lorich DG, Lane JM. Atypical fractures of the femoral diaphysis in postmenopausal women taking alendronate. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1304–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woo SB, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR. Narrative [corrected] review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:753–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bone HG, Hosking D, Devogelaer JP, Tucci JR, Emkey RD, Tonino RP, et al. Ten years' experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1189–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Black DM, Kelly MP, Genant HK, Palermo L, Eastell R, Bucci-Rechtweg C, Cauley J, Leung PC, Boonen S, Santora A, et al. Bisphosphonates and fractures of the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1761–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.National Osteoporosis Foundation Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2010 [Google Scholar]