Abstract

Biologic scaffolds composed of extracellular matrix (ECM) have been used successfully in preclinical models and humans for constructive remodeling of functional, site-appropriate tissue after injury. The mechanisms underlying ECM-mediated constructive remodeling are not completely understood, but scaffold degradation and site-directed recruitment of progenitor cells are thought to play critical roles. Previous studies have identified a cryptic peptide derived from the C-terminal telopeptide of collagen IIIα that has chemotactic activity for progenitor cells. The present study characterized the osteogenic activity of the same peptide in vitro and in vivo in an adult murine model of digit amputation. The present study showed that the cryptic peptide increased calcium deposition, alkaline phosphatase activity, and osteogenic gene expression in human perivascular stem cells in vitro. Treatment with the cryptic peptide in a murine model of mid-second phalanx digit amputation led to the formation of a bone nodule at the site of amputation. In addition to potential therapeutic implications for the treatment of bone injuries and facilitation of reconstructive surgical procedures, cryptic peptides with the ability to alter stem cell recruitment and differentiation at a site of injury may serve as powerful new tools for influencing stem cell fate in the local injury microenvironment.

Introduction

Biologic scaffolds composed of extracellular matrix (ECM) have been used to promote site-specific, functional remodeling of tissue in both preclinical animal models1–10 and human clinical applications.11–14 Although the mechanisms of action of ECM scaffolds are not completely understood, rapid proteolytic degradation of the ECM scaffold15 and subsequent progenitor cell recruitment are thought to be important factors underlying the constructive tissue remodeling process.16–18 After implantation of a noncrosslinked ECM scaffold at a site of injury, a dense mononuclear infiltrate19,20 degrades the scaffold over the course of 60–90 days.21,22 The degradation of the ECM scaffolds results in the release of small cryptic peptides with novel bioactivity not present in the parent ECM proteins.23,24 These cryptic fragments have been shown to possess antimicrobial, immunomodulatory, angiogenic and antiangiogenic, mitogenic, and chemotactic properties, among others.24–31 Additionally, cryptic fragments of ECM proteins have also been shown to be able to regulate the chemotaxis of a variety of progenitor cell populations in vitro and in vivo.18,32–35 However, the ability of cryptic peptides to alter differentiation of progenitor cells in vitro or in vivo has not been previously reported.

A specific cryptic peptide derived from the C-terminal telopeptide region of the collagen IIIα subunit, IAGVGGEKSGGF, was recently isolated and shown to have potent in vitro and in vivo chemotactic activity for multiple progenitor cells including human perivascular stem cells (PSCs).36 The present study shows that the same cryptic peptide can also influence the osteogenic differentiation of human PSCs in vitro. Many ECM-associated proteins have been implicated in osteogenic differentiation after injury, and the expression of matrix metalloproteinases and subsequent ECM degradation are both important contributors to bone remodeling.37 However, it is not known whether the cryptic peptides released from ECM degradation may themselves also have the ability alter bone remodeling. Thus, the present study characterizes the osteogenic activity of a recently described cryptic peptide in vitro and in vivo in an adult mammalian model of digit amputation.36

Materials and Methods

Overview of experimental design

The experimental methods were designed to address the hypothesis that an isolated cryptic peptide, IAGVGGEKSGGF,36 alters osteogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Osteogenesis in vitro was assessed by measuring calcium deposition, alkaline phosphatase activity, and RNA expression of osteogenic markers via quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Osteogenesis was investigated in vivo in an established adult mammalian model of digit amputation.18,38,39 The deposition of calcium was determined by histologic examination as well as by injection of calcium dyes.

Peptide synthesis

A previously identified chemotactic cryptic peptide, IAGVGGEKSGGF,36 was chemically synthesized (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ). The peptide was reconstituted to a final stock concentration of 10 mM in sterile filtered calcium and magnesium free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Source of cells and culture conditions

Human PSCs33 were isolated and prepared as previously described.33,40 PSCs were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo, Pittsburgh, PA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C in 5% CO2. PSCs were characterized by immunolabeling and flow cytometry. Human cortical neuroepithelial stem cells (CTX) and human spinal cord neural stem cells (SPC) were a gift from ReNeuron™. CTX cells were cultured in DMEM:F12 supplemented with 0.03% human albumin solution, 100 μg/mL human apo-transferrin, 16.2 μg/mL putrescine DiHCl, 5 μg/mL insulin, 60 ng/mL progesterone, 2 mM L-glutamine, 40 ng/mL sodium selenite, 10 ng/mL human basic fibroblast growth factor, 20 ng/mL human epidermal growth factor, and 100 nM 4-hydroxytestosterone.

Flow cytometry and immunolabeling of PSCs

Cells were detached from culture flasks using pre-warmed 15 mM sodium citrate for 5 min, centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min, resuspended, and filtered through a 70 μm filter before incubation with antibodies, all at a dilution of 1 μL per 1×107 cells/mL, for 1 h before extensive washing and resuspension with PBS for flow cytometric analysis. Antibodies included mouse monoclonal FITC-CD144 (clone 55-7H1, #560874), APC-CD34 (clone 581, #560940), PE-CD146, and V450-CD45 (clone HI30, #560368) (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). For immunolabeling, 1×105 cells were cytospun onto slides and fixed for 30 s in ice-cold methanol. After permeablization in 0.1% TritonX and 0.1% Tween20 in PBS for 15 min, cells were blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin diluted with 0.01% TritonX and 0.01% Tween20 in PBS for 1 h. Cells were then stained for 1 h with CD146 (clone P1H12) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, ab24577), smooth muscle actin (clone 1A4) (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, M0851), or NG2 (Millipore, Billercia, MA, AB5320), each diluted 1:200 in blocking solution. After extensive washing in PBS, cells were then incubated with donkey anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 546 (Invitrogen, A10042) and donkey anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A21202) diluted 1:400 in blocking buffer for 1 h.

In vitro osteogenic differentiation and Alizarin red stain

PSC, CTX, or SPC cells were seeded at a density of 2×104 cells/well in 24-well plates. After attachment, cells were cultured in either normal culture medium or osteogenic differentiation medium, consisting of DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, G9422), and 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma, A4544). Wells were supplemented to a final concentration of 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM of the cryptic peptide. At days 4, 7, 14, and 21, wells were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and stained with 40 mM Alizarin red at pH 4.1 (Sigma, A5533). Semiquantitative analysis of alizarin red staining was completed as previously described.41 Briefly, wells were stained for 20 min with 40 mM alizarin red and then washed twice with distilled H2O. After washing, wells were incubated in 400 μL of 10% acetic acid until complete de-staining was achieved. Each well was then neutralized with 160 μL of 10% ammonium hydroxide. The optical density of each sample to 405 nm wavelength light was then read measured on a spectrophotometer.

Alkaline phosphatase staining

PSCs were seeded at a density of 2×104 cells/well in 24-well plates. At day 7 postculture in either normal growth medium or osteogenic differentiation medium supplemented with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM of peptide, cells were fixed for 2 min in 10% neutral buffered formalin. A subset of wells were incubated in an alkaline phosphatase substrate (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, SK-5100) and imaged. Semiquantitative analysis of alkaline phosphatase activity was completed by incubating the second subset of wells in 0.5 mg/mL p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Thermo, #37620) for 30 min at 37°C in the dark before measuring the optical density of each sample to 405 nm light using a spectrophotometer.

Adipogenic differentiation

PSCs were seeded in wells at a density of 2×104 cells/well in 24-well plates. After cell attachment, cells were cultured in normal culture medium or adipogenic differentiation medium (Hyclone, Pittsburgh, PA, SH30886.02). Cells were fixed at days 7 and 14 in 10% neutral buffered formalin before staining with 0.5% Oil Red O solution (Alfa Aeasar, Ward Hill, MA) in 3:2 isopropanol:distilled H2O for 30 min. After washing twice with distilled H2O. Semiquantitative analysis of Oil Red O staining was completed as previously described.42 Briefly, wells were de-stained in 100% isopropanol for 30 min. Aliquots of each well were then read on a spectrophotometer for absorbance at 490 nm wavelength.

PCR studies

After culture of PSCs in culture medium or osteogenic medium supplemented with either 0 or 100 μM peptide, cells were cultured for 4, 7, or 14 days. Cells were then incubated in Trizol solution (Invitrogen, 11596-018) for 15 min at room temperature. RNA was extracted from Trizol solutions using phenol-chloroform extraction, and RNA was converted to cDNA using DNA Superscript Assay (Invitrogen, 18080). Real-time quantitative PCR was then conducted using SYBR green dye (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, 4385614) on a BioRad iCycler iQ5 PCR machine. After initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, PCR was run for 45 cycles, with each cycle consisting of: (1) melting at 95°C for 10 s, (2) annealing for 30 s, and (3) extension at 72°C for 30 s. PCR was carried out for osteogenic, chondrogenic, adipogenic, and housekeeping genes (Table 1). The annealing temperature for Col1, SPP1, LPL, and 1HAT was 60°C, and the annealing temperature for ABCB1 and Runx2 was 62°C. A housekeeping gene control, 23s, was run simultaneously for each gene marker at each annealing temperature.

Table 1.

Polymerase Chain Reaction Primers and Accession Numbers Used for Reverse Transcriptase-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

| Marker | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) | Accession number | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPP1 | CTCCATTGACTCGAACGACTC | CAGGTCTGCGAAACTTCTTAGAT | NM_000582 | 230 |

| Col1 | ATGGATTCCAGTTCGAGTATGGC | CATCGACAGTGACGCTGTAGG | NM_000088 | 246 |

| 1HAT | AACTGCTTTTGGTTACAAGGGT | GAAGTAAGGTTCCGAATGGCTT | NM_003642 | 239 |

| ABCB1 | GGGAGCTTAACACCCGACTTA | GCCAAAATCACAAGGGTTAGCTT | NM_000927 | 154 |

| Runx2 | AGATGATGACACTGCCACCTCTG | GGGATGAAATGCTTGGGAACTGC | NM_001024630 | 125 |

| LPL | AGGAGCATTACCCAGTGTCC | GGCTGTATCCCAAGAGATGGA | NM_000237 | 126 |

| 23s | GCACAGCCCTAAAGGCCAACCC | TCACCAACAGCATGACCTTTGCG | NM_001025 | 243 |

Animal model of digit amputation

All methods were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh and performed in compliance with NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mid-second phalanx digit amputation of the third digit on each hindfoot in adult 6–8-week-old C57/BL6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) was completed as previously described.18 After amputation, digits were either treated with a subcutaneous injection of 15 μL of 10 mM peptide (150 μg peptide), or the same volume of PBS as a carrier control (n=4 for each group). The volume and concentration of the peptide were chosen to be consistent with previous studies utilizing similar treatments in the same model of injury.18,36 Treatments were administered at 0, 24, and 96 h postsurgery. Animals were sacrificed via cervical dislocation under deep isoflurane anesthesia (5%–6%) at days 7, 14, 18, or 28 postsurgery. Digits were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, decalcified for 2 weeks in 10% formic acid, and then sectioned at 5 μm thickness on to slides for further staining. Slides were either stained with Masson's trichrome stain or Alcian blue stain.

Histomorphometric analysis of bone growth

As per guidelines of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, histomorphometric analysis of Masson's trichrome stained histologic sections of amputated digits was completed by measurement of the total bone callous area on each section.43,44 Measurements of area were made using ImageJ (NIH) by a user blinded to the treatment group.

Calcium dye studies and optical clearance of tissue

Analysis of in vivo calcium deposition was adapted from previous studies.45,46 Three days before digit amputation, mice were injected intraperitoneal (IP) with 3.5 mg/kg green calcein dye (Invitrogen, C481). Mice then were subjected to digit amputation and treatment. One day before harvest, mice were injected IP with 50 mg/kg alizarin red calcium dye (Sigma, A5533). Animals were sacrificed on day 14 postamputation via cervical dislocation under deep isoflurane anesthesia (5%–6%). Isolated digits were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde before serial dehydration in 25%, 50%, 75%, 95%, and 100% acetone. After dehydration, fixed digits were then incubated in Dent's fixative (1:4 dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]:acetone) for 2 h. Then, the digits were permeablized and bleached overnight in Dent's bleach (1:4:1 DMSO:acetone:H2O2). Digits were then equilibrated to a clearing solution consisting of 1:2 benzyl alcohol (Sigma, 402834) to benzyl benzoate (Sigma, B6630) (BABB) by serial 1 h incubations in 1:3, 1:1, and 3:1 solutions of BABB:Dent's fixative. Digits were then kept in 100% BABB until they were visibly optically cleared. Optically cleared digits were then imaged using a Nikon E600 epifluorescence microscope at 100× magnification, and images were taken with a Nuance camera. Images were deconvolved with known spectra for alizarin red and calcein dye to identify new versus old depositions of calcium.

Results

Characterization of PSCs

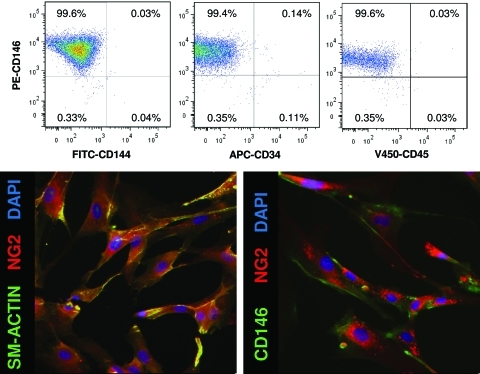

Human PSCs were cultured through passages 11–14. To confirm that the cells had not changed in culture, the expression of various markers of PSCs was investigated via flow cytometry. PSCs expressed mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) markers CD146, NG2, and smooth muscle actin. However, they did not express endothelial cell marker, CD144. Additionally, as previously described,33,35 PSCs did not express markers of blood lineage, CD34 and CD45. PSCs remained CD146+, NG2+, sm-actin+, CD144−, CD34−, CD45− through culture of passages 11–14 in vitro (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Perivascular stem cells express mesenchymal stem cell markers. Human perivascular stem cells were characterized by flow cytometry and immunostaining to confirm their phenotype as perivascular stem cells. As previously described,33 perivascular stem cells did not express CD144, CD34, or CD45. They did express perivascular stem cell markers CD146, NG2, and smooth muscle actin.33 Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

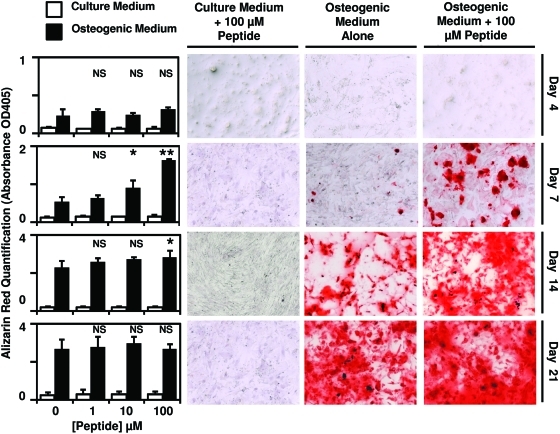

Peptide accelerates osteogenesis in vitro

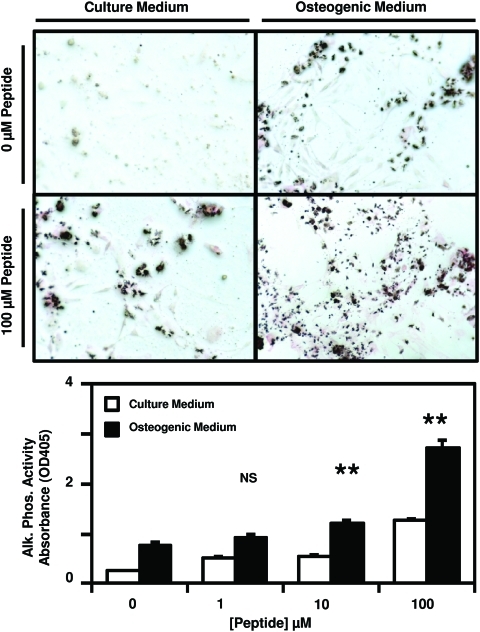

After culture of PSCs in either normal growth medium or osteogenic differentiation medium supplemented with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM peptide, calcium deposition by the cells was measured by Alizarin red staining. There was a dose-dependent increase in Alizarin red staining at days 7 and 14 post-treatment (Fig. 2). By day 21 post-treatment, no significant difference in Alizarin red staining was observed between treatment groups. Culture of PSCs in normal growth medium supplemented with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM peptide did not result in any changes in Alizarin red staining at any time point (Fig. 2), suggesting that the isolated cryptic peptide accelerates osteogenesis only in conditions of osteogenic differentiation. Concomitant with increased calcium deposition, a dose-dependent increase in alkaline phosphatase activity was observed on day 7 post-treatment with peptide in conditions of osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Cryptic peptide accelerates osteogenesis of perivascular stem cells. Human perivascular stem cells were cultured in either normal culture medium or osteogenic differentiation medium. After supplementation of medium with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM of the isolated cryptic peptide, osteogenic differentiation was determined by Alizarin red stain of the cells. At 7 and 14 days postdifferentiation, the isolated cryptic peptide accelerated osteogenesis of perivascular stem cells. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 as compared to the 0 μM osteogenic differentiation group. Error bars represent mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) of experiments in triplicate (n=3). NS, not significant. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

FIG. 3.

Cryptic peptide increases alkaline phosphatase activity. Human perivascular stem cells were cultured in either culture medium or osteogenic differentiation medium. After supplementation of medium with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM of the isolated cryptic peptide, alkaline phosphatase activity was measured by p-Nitrophenyl phosphate substrate reaction and staining. At 7 days postdifferentiation and treatment, the isolated cryptic peptide resulted in increased alkaline phosphatase activity. **p<0.01 as compared to the 0 μM osteogenic differentiation group. Error bars represent mean±SEM of experiments in triplicate (n=3). Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

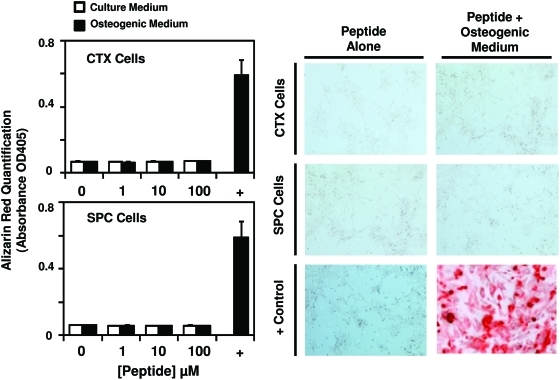

To determine whether the peptide promotes osteogenesis in stem cells not known to show osteogenic differentiation potential, human cortical neuroepithelial stem cells (CTX) and spinal cord neural stem cells (SPC) were cultured in normal growth medium or osteogenic differentiation medium supplemented with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM peptide. PSCs cultured in osteogenic differentiation medium with no supplement were used as a positive control. At day 7 post-treatment, peptide treatment in normal growth medium or osteogenic differentiation medium did not result in calcium deposition and Alizarin red staining of CTX and SPC cells (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Cryptic peptide does not promote osteogenic differentiation in non-osteogenic stem cells. To determine whether the isolated cryptic peptide promotes osteogenic differentiation of nonmesenchymal stem cells, human cortical neuroepithelial stem cells and human spinal cord neural stem cells were cultured in normal culture medium or osteogenic differentiation medium in the presence of 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM of the isolated cryptic peptide. The isolated peptide did not promote osteogenic differentiation of the neural stem cells. Error bars represent mean±SEM of experiments in triplicate (n=3). Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

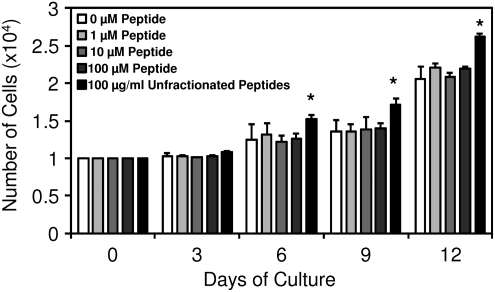

To confirm that the observed in vitro calcium deposition was due to true osteogenesis and not secondary to necrotic ossification from overgrowth of cells, the ability of the peptide to induce proliferation in PSCs was assessed. Although unfractionated ECM degradation products induced mitogenesis of PSCs, consistent with previous studies,35 no change in PSC proliferation was observed in response to treatment with the cryptic peptide (Fig. 5). Because no differences were noted in cell number between peptide-treated groups and negative controls, the calcium deposition observed in response to peptide treatment cannot be secondary to selective overgrowth in peptide-treated groups.

FIG. 5.

Cryptic peptide does not alter proliferation of perivascular stem cells. To determine whether the peptide induced osteogenesis by increasing proliferation of cells, perivascular stem cells were supplemented in normal growth medium supplemented with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM peptide, or 100 μg/mL of unfractionated cryptic peptides as a positive control.35 Over the course of 12 days, no change in cell number was observed after culture in any concentration of cryptic peptide. *p<0.05 as compared to normal growth medium at each time point. Error bars represent mean±SEM of experiments in triplicate (n=3).

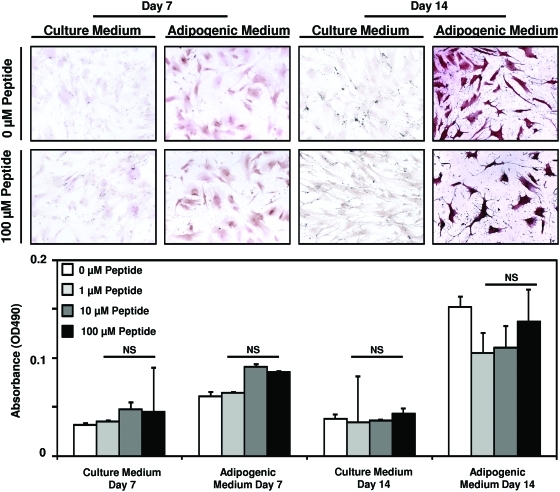

Peptide does not alter adipogenesis in vitro

To determine whether the peptide alters the differentiation of PSCs along other mesenchymal lineages in addition to osteogenesis, PSCs were cultured in normal growth medium or adipogenic differentiation medium supplemented with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM peptide. Although an increase in Oil Red O staining was noted in conditions of adipogenic differentiation at days 7 and 14 post-treatment, peptide treatment did not alter the rate of adipogenesis (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Cryptic peptide does not alter adipogenesis of perivascular stem cells. Human perivascular stem cells were cultured in either culture medium or adipogenic differentiation medium. After supplementation of medium with 0, 1, 10, or 100 μM of the isolated cryptic peptide, differentiation was determined by Oil Red O stain. No differences were noted between treatment groups at any time point. Error bars represent mean±SEM of experiments in triplicate (n=3). Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

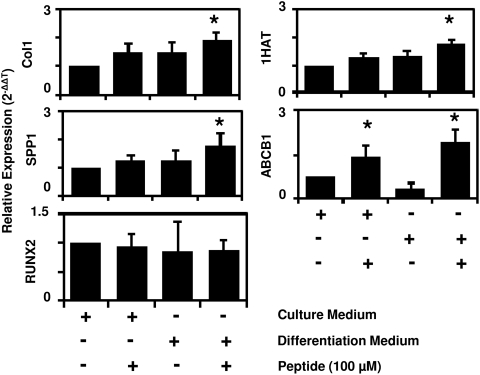

Peptide promotes expression of osteogenic and chondrogenic markers in human PSCs

To determine the specificity of cryptic peptide-mediated differentiation for osteogenesis, changes in mRNA expression of osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic genes were determined after culture of PSCs in either normal growth medium, growth medium supplemented with 100 μM cryptic peptide, osteogenic differentiation medium alone, or osteogenic medium supplemented with 100 μM cryptic peptide. At 4 days postculture, peptide treatment did not significantly change the expression of osteogenic genes Collagen I, Runx2, or Osteopontin (SPP1). However, supplementation of the peptide in osteogenic medium resulted in a significant increase in Collagen I and Osteopontin expression in PSCs (Fig. 7). Peptide treatment alone also resulted in a significant increase in the expression of the chondrogenic gene, ABCB1, and peptide supplementation of osteogenic medium resulted in a significant increase in expression of both chondrogenic genes, ABCB1 and 1HAT (Fig. 7). No mRNA expression of lipoprotein lipase, a marker of adipogenesis, was observed through 45 cycles of RT-qPCR.

FIG. 7.

Cryptic peptide increases expression of osteogenic and chondrogenic genes in vitro. To determine whether the cryptic peptide accelerates osteogenesis by increasing mRNA expression of osteogenic genes, perivascular stem cells were cultured for 4 days in normal growth medium or osteogenic medium unsupplemented or supplemented with 100 μM cryptic peptide. Osteogenic medium supplemented with peptide resulted in a significant increase in Collagen I, Osteopontin (SPP1), 1HAT, and ABCB1 expression. No expression of LPL was observed over 45 cycles of reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. *p<0.05 as compared to normal growth medium for each gene. Error bars represent mean±SEM of six experiments (n=6).

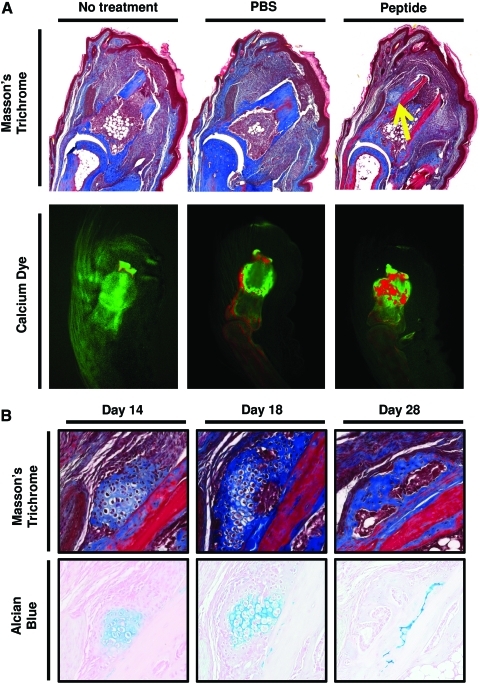

Peptide promotes bone formation in vivo

To determine whether the peptide treatment can promote bone formation in vivo, a previous established model of murine digit amputation was utilized.18,38,39 After mid-second phalanx amputation and treatment with the cryptic peptide, Masson's trichrome staining of histologic sections at day 14 postamputation showed the presence of a bone-like nodule just lateral to the amputated P2 bone that was not present in PBS or untreated amputated digits (Fig. 8A). Differential calcium dye stains were utilized as previously described45,46 to determine whether there was new calcium deposition at the site of amputation after peptide treatment. After initial injection with a green calcein dye to label all bones green, mice were subjected to mid-second phalanx amputation and treatment. On day 14 postamputation, mice were injected with a second dye, Alizarin red, to label all new deposited calcium red. After peptide treatment, more new calcium deposition was noted in the amputated P2 bone (Fig. 8A). Additionally, Alcian blue and Masson's trichrome staining showed that the bone-like nodule progressed from a glycosaminoglycan-rich structure with at day 14 postamputation toward a collagenous nodule devoid of glycosaminoglycans at day 28 postamputation, suggesting endochondral ossification as the primary mechanism of osteogenesis in vivo (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Cryptic peptide promotes bone deposition in an adult mammalian model of digit amputation. To determine whether the isolated cryptic peptide promotes osteogenesis in vivo, adult C57/BL6 mice were subjected to mid-second phalanx amputation and either left untreated, treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) carrier control, or treated with the isolated cryptic peptide. (A) At day 14 postamputation, histologic analysis revealed a bone-like nodule present at the site of amputation in the peptide treated group. Differential calcium dye injections showed that peptide treatment increases calcium deposition at the site of amputation. (B) Alcian blue stain showed that the bone nodule stained positive for glycosaminoglycans at early time points, suggesting that the nodule underwent endochondral ossification. Images are representative of n=4 animals in each treatment group. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

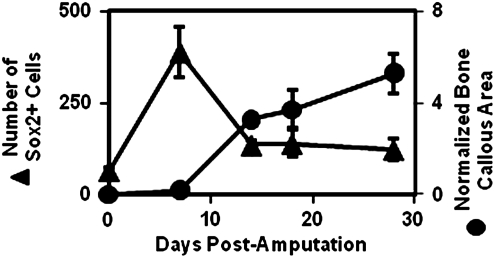

Previous work has shown that Sox2+, Sca1+, Lin− cells are recruited to a site of digit amputation after digit amputation and treatment with the isolated cryptic peptide.36 To determine whether Sox2+ cells may contribute to bone formation, a time course analysis of Sox2+ cell accumulation and simultaneous bone nodule formation was completed. Sox2+ cell accumulation peaked at day 7 postamputation, and then steadily decreased over 14–28 days postamputation. Conversely, histomorphometric analysis of the bone nodule formation showed that the bone nodule formation steadily increased in size over 14–28 days postamputation as the number of Sox2+ cells decreased (Fig. 9). These findings suggest a role for the Sox2+ cells in bone nodule formation, consistent with previous studies showing the importance of Sox2 in osteogenesis.47,48

FIG. 9.

Bone nodule formation correlates with a loss of Sox2+ cells. To determine whether Sox2+ cells may play a role in bone formation, a time course analysis of the accumulation of Sox2+ cells and bone growth43,44 was completed after peptide treatment. After a peak in Sox2+ cell accumulation at 7 days postamputation, a sharp decrease in Sox2+ cells coincided with the histologic appearance and growth of a bone nodule at the site of amputation, consistent with previous studies showing a role for Sox2 in osteogenesis.47,48 Error bars represent mean±SEM of experiments in quadruplicate (n=4).

Discussion

The present study identified a novel property of a cryptic peptide previously shown to possess chemotactic activity for progenitor cells.36 In the present study, the same cryptic peptide accelerated osteogenic differentiation of human PSCs. Treatment with the cryptic peptide at a site of digit amputation in vivo resulted in the formation of calcified bone at the site of amputation. An increasing body of literature has begun to recognize the importance of cryptic fragments of proteins that contain novel activity not associated with their parent molecules. Collectively referred to as the “cryptome,”23,24,49–53 various peptides have been identified to show bioactive properties including antimicrobial, pro- and anti-angiogenic, chemotactic, and mitogenic activity.24–31 The present study shows that such cryptic peptides may also be able to affect the differentiation of stem cells. Since stem cell are known to home to sites of inflammation and participate in the injury response, the release of cryptic peptides with the ability to alter stem cell differentiation at the site of injury may be a conserved, desirable response to promote tissue reconstruction after injury.

The cryptic peptide used in the present study is derived from the C-terminal telopeptide of collagen III, a region known to be enzymatically cleaved and released into the circulation after soft tissue injury.54–56 However, most trauma does not lead to spontaneous bone formation at the site of injury secondary to the release of cryptic peptides such as the one identified in the present study. After an injury, there are likely thousands of peptides released from wound sites, and the cryptic peptide in the present study would only be one of many peptides that exert an overall net effect upon differentiation of local stem cells. It is likely that cryptic peptides exist that could not only promote differentiation of stem cells, as shown in the present study, but also inhibit differentiation.57 The present study investigated the activity of a single cryptic peptide by injecting supra-physiologic concentrations in vivo, many orders of magnitude greater than the concentrations of other cryptic peptides that would be expected to be released from a site of digit amputation.

Second, the findings of the present study show that the cryptic peptide depends on an osteogenic microenvironment to promote osteogenesis in vitro and in vivo. The dependence of the cryptic peptide's osteogenic activity upon the microenvironment is an interesting property with potential therapeutic implications. There are many well-known osteogenic growth factors such as bone morphogenetic protein that have been used with varying degrees of success to induce and/or promote bone growth in vivo.58,59 However, in many cases, these growth factors have other side effects, including heterotopic ossification at sites where osteogenesis is not desired.60 The cryptic peptide in the present study only enhanced osteogenesis of PSCs in vitro when cultured in the presence of osteogenic differentiation medium. Additionally, peptide treatment only resulted in the formation of a bone nodule lateral to the amputated bone at the site of amputation, that is, an active site of periosteal injury/inflammation. Bone injury in vivo locally activates pathways of bone deposition and osteogenesis.61 Further, injury to the periosteum that surrounds the bone activates latent MSCs within the periosteum62 to promote osteogenesis.63 The present study found bone nodule formation in vivo only lateral to the bone, consistent with a location where activated periosteal MSCs would likely promote osteogenesis.

The microenvironmental niche at a site of injury is a complex, important determinant of a host response to injury.64 Previous studies have extensively examined the role of the microenvironmental niche in controlling stem cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation.65 In addition to cues from nearby cells66 and biophysical cues from the environment,67 extracellular cues are thought to regulate stem cell behavior in an injury microenvironment.68–71 While the present study shows a novel property of cryptic peptides that may contribute to the regulation of stem cell behavior at a site of injury, it also shows that the microenvironment itself plays a reciprocal role in altering the activity of cryptic peptides. In the absence of osteogenic differentiation conditions, the cryptic peptide utilized in the present study shows no osteogenic activity. Additionally, the peptide only induced bone formation at a site of amputation in vivo. It is possible that a costimulatory growth factor or molecule is present in an osteogenic microenvironment that is necessary for the peptide's mode of action. It is also possible that the cryptic peptide activates a signaling pathway that acts in synergy with existing activated osteogenic signaling pathways to enhance osteogenesis. An attractive target of action of the cryptic peptide in the present study is via modulation of integrin signaling pathways.72–74 Integrins are important in both osteogenesis75 and stem cell chemotaxis,76 both properties of the cryptic peptide in the present study. Future studies will further investigate these mechanisms.

In summary, the present study identified a novel property of a cryptic peptide derived from C-terminal telopeptide region of the collagen IIIα molecule. The cryptic peptide selectively enhanced osteogenesis in vitro and in vivo only at a site of injury in a mouse model of digit amputation. While further work is necessary to identify the mechanisms of action of the cryptic peptide, the identification of cryptic peptides capable of altering stem cell differentiation is a novel property not previously attributed to cryptic peptides. In addition to potential therapeutic implications for the treatment of bone injuries and chronic diseases, cryptic peptides with the ability to alter stem cell recruitment and differentiation at a site of injury may serve as powerful new tools for influencing stem cell fate in the local microenvironmental niche.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Deanna Rhoads of the McGowan Histology Center for her assistance in histologic section preparation, and Chris Medberry for his assistance in production of the ECM bioscaffolds. The authors also thank Lynda Guzik and Eric Lagasse for access and assistance in operating flow cytometric equipment. The authors acknowledge the Harvard Primer Bank (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/) for the design of select primers used in the present study. This work was supported by the Armed Forces Institute for Regenerative Medicine grant W81XWH-08-2-0032 and NIH training fellowship grant 1F30-HL102990.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Caione P. Capozza N. Zavaglia D. Palombaro G. Boldrini R. In vivo bladder regeneration using small intestinal submucosa: experimental study. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22:593. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobb M.A. Badylak S.F. Janas W. Boop F.A. Histology after dural grafting with small intestinal submucosa. Surg Neurol. 1996;46:389. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00202-9. discussion 93–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lantz G.C. Badylak S.F. Coffey A.C. Geddes L.A. Blevins W.E. Small intestinal submucosa as a small-diameter arterial graft in the dog. J Invest Surg. 1990;3:217. doi: 10.3109/08941939009140351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodde J.P. Badylak S.F. Shelbourne K.D. The effect of range of motion on remodeling of small intestinal submucosa (SIS) when used as an achilles tendon repair material in the rabbit. Tissue Eng. 1997;3:27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uygun B.E. Soto-Gutierrez A. Yagi H. Izamis M.L. Guzzardi M.A. Shulman C., et al. Organ reengineering through development of a transplantable recellularized liver graft using decellularized liver matrix. Nat Med. 2010;16:814. doi: 10.1038/nm.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ott H.C. Clippinger B. Conrad C. Schuetz C. Pomerantseva I. Ikonomou L., et al. Regeneration and orthotopic transplantation of a bioartificial lung. Nat Med. 2010;16:927. doi: 10.1038/nm.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott H.C. Matthiesen T.S. Goh S.K. Black L.D. Kren S.M. Netoff T.I., et al. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:213. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badylak S. Meurling S. Chen M. Spievack A. Simmons-Byrd A. Resorbable bioscaffold for esophageal repair in a dog model. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1097. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2000.7834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badylak S.F. Lantz G.C. Coffey A. Geddes L.A. Small intestinal submucosa as a large diameter vascular graft in the dog. J Surg Res. 1989;47:74. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(89)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zalavras C.G. Gardocki R. Huang E. Stevanovic M. Hedman T. Tibone J. Reconstruction of large rotator cuff tendon defects with porcine small intestinal submucosa in an animal model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:224. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metcalf M.H. Savoie F.H. Kellum B. Surgical technique for xenograft (SIS) augmentation of rotator-cuff repairs. Oper Tech Orthop. 2002;12:204. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derwin K.A. Badylak S.F. Steinmann S.P. Iannotti J.P. Extracellular matrix scaffold devices for rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:467. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mase V.J., Jr. Hsu J.R. Wolf S.E. Wenke J.C. Baer D.G. Owens J., et al. Clinical application of an acellular biologic scaffold for surgical repair of a large, traumatic quadriceps femoris muscle defect. Orthopedics. 2010;33:511. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100526-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witteman B.P. Foxwell T.J. Monsheimer S. Gelrud A. Eid G.M. Nieponice A., et al. Transoral endoscopic inner layer esophagectomy: management of high-grade dysplasia and superficial cancer with organ preservation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2104. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valentin J.E. Stewart-Akers A.M. Gilbert T.W. Badylak S.F. Macrophage participation in the degradation and remodeling of extracellular matrix scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1687. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zantop T. Gilbert T.W. Yoder M.C. Badylak S.F. Extracellular matrix scaffolds are repopulated by bone marrow-derived cells in a mouse model of achilles tendon reconstruction. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1299. doi: 10.1002/jor.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badylak S.F. Park K. Peppas N. McCabe G. Yoder M. Marrow-derived cells populate scaffolds composed of xenogeneic extracellular matrix. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:1310. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00729-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal V. Johnson S.A. Reing J. Zhang L. Tottey S. Wang G., et al. Epimorphic regeneration approach to tissue replacement in adult mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905851106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badylak S.F. Valentin J.E. Ravindra A.K. McCabe G.P. Stewart-Akers A.M. Macrophage phenotype as a determinant of biologic scaffold remodeling. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1835. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valentin J.E. Badylak J.S. McCabe G.P. Badylak S.F. Extracellular matrix bioscaffolds for orthopaedic applications. A comparative histologic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2673. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert T.W. Stewart-Akers A.M. Badylak S.F. A quantitative method for evaluating the degradation of biologic scaffold materials. Biomaterials. 2007;28:147. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Record R.D. Hillegonds D. Simmons C. Tullius R. Rickey F.A. Elmore D., et al. In vivo degradation of 14C-labeled small intestinal submucosa (SIS) when used for urinary bladder repair. Biomaterials. 2001;22:2653. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis G.E. Matricryptic sites control tissue injury responses in the cardiovascular system: relationships to pattern recognition receptor regulated events. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:454. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis G.E. Bayless K.J. Davis M.J. Meininger G.A. Regulation of tissue injury responses by the exposure of matricryptic sites within extracellular matrix molecules. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1489. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65020-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:710. doi: 10.1038/nri1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore A.J. Beazley W.D. Bibby M.C. Devine D.A. Antimicrobial activity of cecropins. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:1077. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.6.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore A.J. Devine D.A. Bibby M.C. Preliminary experimental anticancer activity of cecropins. Pept Res. 1994;7:265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berkowitz B.A. Bevins C.L. Zasloff M.A. Magainins: a new family of membrane-active host defense peptides. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;39:625. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90138-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F. Li W. Johnson S. Ingram D. Yoder M. Badylak S. Low-molecular-weight peptides derived from extracellular matrix as chemoattractants for primary endothelial cells. Endothelium. 2004;11:199. doi: 10.1080/10623320490512390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adair-Kirk T.L. Senior R.M. Fragments of extracellular matrix as mediators of inflammation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1101. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agrawal V. Brown B.N. Beattie A.J. Gilbert T.W. Badylak S.F. Evidence of innervation following extracellular matrix scaffold-mediated remodelling of muscular tissues. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3:590. doi: 10.1002/term.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brennan E.P. Tang X.H. Stewart-Akers A.M. Gudas L.J. Badylak S.F. Chemoattractant activity of degradation products of fetal and adult skin extracellular matrix for keratinocyte progenitor cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2008;2:491. doi: 10.1002/term.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crisan M. Yap S. Casteilla L. Chen C.W. Corselli M. Park T.S., et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reing J.E. Zhang L. Myers-Irvin J. Cordero K.E. Freytes D.O. Heber-Katz E., et al. Degradation products of extracellular matrix affect cell migration and proliferation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:605. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tottey S. Corselli M. Jeffries E.M. Londono R. Peault B. Badylak S.F. Extracellular matrix degradation products and low-oxygen conditions enhance the regenerative potential of perivascular stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:37. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agrawal V. Tottey S. Johnson S.A. Freund J. Siu B.F. Badylak S.F. Recruitment of progenitor cells by an ECM cryptic peptide in a mouse model of digit amputation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0036. [Epub ahead of print]; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alford A.I. Hankenson K.D. Matricellular proteins: extracellular modulators of bone development, remodeling, and regeneration. Bone. 2006;38:749. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schotte O.E. Smith C.B. Wound healing processes in amputated mouse digits. Biol Bull. 1959;117:546. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schotte O.E. Smith C.B. Effects of ACTH and of cortisone upon amputational wound healing processes in mice digits. J Exp Zool. 1961;146:209. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401460302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tottey S. Corselli M. Jeffries E.M. Londono R. Peault B. Badylak S.F. Extracellular matrix degradation products and low-oxygen conditions enhance the regenerative potential of perivascular stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:37. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gregory C.A. Gunn W.G. Peister A. Prockop D.J. An Alizarin red-based assay of mineralization by adherent cells in culture: comparison with cetylpyridinium chloride extraction. Anal Biochem. 2004;329:77. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trouba K.J. Wauson E.M. Vorce R.L. Sodium arsenite inhibits terminal differentiation of murine C3H 10T1/2 preadipocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;168:25. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parfitt A.M. Drezner M.K. Glorieux F.H. Kanis J.A. Malluche H. Meunier P.J., et al. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 1987;2:595. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holstein J.H. Klein M. Garcia P. Histing T. Culemann U. Pizanis A., et al. Rapamycin affects early fracture healing in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1055. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neufeld D.A. Zhao W. Bone regrowth after digit tip amputation in mice is equivalent in adults and neonates. Wound Repair Regen. 1995;3:461. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1995.30410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao W. Neufeld D.A. Bone regrowth in young mice stimulated by nail organ. J Exp Zool. 1995;271:155. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402710212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Basu-Roy U. Ambrosetti D. Favaro R. Nicolis S.K. Mansukhani A. Basilico C. The transcription factor Sox2 is required for osteoblast self-renewal. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1345. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mansukhani A. Ambrosetti D. Holmes G. Cornivelli L. Basilico C. Sox2 induction by FGF and FGFR2 activating mutations inhibits Wnt signaling and osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:1065. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Autelitano D.J. Rajic A. Smith A.I. Berndt M.C. Ilag L.L. Vadas M. The cryptome: a subset of the proteome, comprising cryptic peptides with distinct bioactivities. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:306. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mukai H. Seki T. Nakano H. Hokari Y. Takao T. Kawanami M., et al. Mitocryptide-2: purification, identification, and characterization of a novel cryptide that activates neutrophils. J Immunol. 2009;182:5072. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mukai H. Hokari Y. Seki T. Takao T. Kubota M. Matsuo Y., et al. Discovery of mitocryptide-1, a neutrophil-activating cryptide from healthy porcine heart. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803913200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ng J.H. Ilag L.L. Cryptic protein fragments as an emerging source of peptide drugs. IDrugs. 2006;9:343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pimenta D.C. Lebrun I. Cryptides: buried secrets in proteins. Peptides. 2007;28:2403. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kitahara T. Takeishi Y. Arimoto T. Niizeki T. Koyama Y. Sasaki T., et al. Serum carboxy-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (ICTP) predicts cardiac events in chronic heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function. Circ J. 2007;71:929. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banfi G. Lombardi G. Colombini A. Lippi G. Bone metabolism markers in sports medicine. Sports Med. 2010;40:697. doi: 10.2165/11533090-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanoupakis E.M. Manios E.G. Kallergis E.M. Mavrakis H.E. Goudis C.A. Saloustros I.G., et al. Serum markers of collagen turnover predict future shocks in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients with dilated cardiomyopathy on optimal treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2753. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee S.T. Yun J.I. Jo Y.S. Mochizuki M. van der Vlies A.J. Kontos S., et al. Engineering integrin signaling for promoting embryonic stem cell self-renewal in a precisely defined niche. Biomaterials. 2011;31:1219. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dickinson B.P. Ashley R.K. Wasson K.L. O'Hara C. Gabbay J. Heller J.B., et al. Reduced morbidity and improved healing with bone morphogenic protein-2 in older patients with alveolar cleft defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:209. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000293870.64781.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rogozinski A. Rogozinski C. Cloud G. Accelerating autograft maturation in instrumented posterolateral lumbar spinal fusions without donor site morbidity. Orthopedics. 2009;32:809. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20090922-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mannion R.J. Nowitzke A.M. Wood M.J. Promoting fusion in minimally invasive lumbar interbody stabilization with low-dose bone morphogenic protein-2-but what is the cost? Spine J. 2011;11:527. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ai-Aql Z.S. Alagl A.S. Graves D.T. Gerstenfeld L.C. Einhorn T.A. Molecular mechanisms controlling bone formation during fracture healing and distraction osteogenesis. J Dent Res. 2008;87:107. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Bari C. Dell'Accio F. Vanlauwe J. Eyckmans J. Khan I.M. Archer C.W., et al. Mesenchymal multipotency of adult human periosteal cells demonstrated by single-cell lineage analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1209. doi: 10.1002/art.21753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang X. Xie C. Lin A.S. Ito H. Awad H. Lieberman J.R., et al. Periosteal progenitor cell fate in segmental cortical bone graft transplantations: implications for functional tissue engineering. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2124. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lutton C. Goss B. Caring about microenvironments. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:613. doi: 10.1038/nbt0608-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watt F.M. Hogan B.L. Out of Eden: stem cells and their niches. Science. 2000;287:1427. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chow A. Lucas D. Hidalgo A. Mendez-Ferrer S. Hashimoto D. Scheiermann C., et al. Bone marrow CD169+ macrophages promote the retention of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mesenchymal stem cell niche. J Exp Med. 2011;208:261. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keung A.J. Kumar S. Schaffer D.V. Presentation counts: microenvironmental regulation of stem cells by biophysical and material cues. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:533. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Discher D.E. Mooney D.J. Zandstra P.W. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science. 2009;324:1673. doi: 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kienstra K.A. Jackson K.A. Hirschi K.K. Injury mechanism dictates contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to murine hepatic vascular regeneration. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:131. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31815b481c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Majka S.M. Jackson K.A. Kienstra K.A. Majesky M.W. Goodell M.A. Hirschi K.K. Distinct progenitor populations in skeletal muscle are bone marrow derived and exhibit different cell fates during vascular regeneration. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:71. doi: 10.1172/JCI16157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jackson K.A. Majka S.M. Wang H. Pocius J. Hartley C.J. Majesky M.W., et al. Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1395. doi: 10.1172/JCI12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xia M. Zhu Y. Fibronectin fragment activation of ERK increasing integrin alpha(5) and beta(1) subunit expression to degenerate nucleus pulposus cells. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:556. doi: 10.1002/jor.21273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Horton M.A. Spragg J.H. Bodary S.C. Helfrich M.H. Recognition of cryptic sites in human and mouse laminins by rat osteoclasts is mediated by beta 3 and beta 1 integrins. Bone. 1994;15:639. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)90312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Agrez M.V. Bates R.C. Boyd A.W. Burns G.F. Arg-Gly-Asp-containing peptides expose novel collagen receptors on fibroblasts: implications for wound healing. Cell Regul. 1991;2:1035. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.12.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shih Y.R. Tseng K.F. Lai H.Y. Lin C.H. Lee O.K. Matrix stiffness regulation of integrin-mediated mechanotransduction during osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:730. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chavakis E. Aicher A. Heeschen C. Sasaki K. Kaiser R. El Makhfi N., et al. Role of beta2-integrins for homing and neovascularization capacity of endothelial progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:63. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]