Abstract

Introduction

Progressive language impairment is among the primary components of cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease (AD). Because expressive and receptive language help to maintain emotional connections to caregivers and support the management of AD patients' functional needs, language plays a critical role in patients' emotional and physical health. Using data from a large prospective clinical trial comparing two doses of donepezil in patients with moderate to severe AD, we performed a post hoc analysis to determine whether a higher dose of donepezil was associated with greater benefits in language function.

Methods

In the original randomized, double-blind clinical trial, 1,467 patients with moderate to severe AD (baseline Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score 0 to 20) were randomized 2:1 to receive donepezil 23 mg/day or to continue on donepezil 10 mg/day for 24 weeks. In this post hoc analysis, the Severe Impairment Battery-Language scale (SIB-L) and a new 21-item SIB-derived language scale (SIB[lang]) were used to explore differences in language function between the treatment groups. Correlations between SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores and scores on the severe version of the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living inventory (ADCS-ADL-sev), the Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Severity-plus caregiver input/Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input (CIBIS-plus/CIBIC-plus) and the MMSE were also investigated.

Results

At week 24, treatment with donepezil 23 mg/day was associated with an improvement in language in the full intention-to-treat population, whereas language function declined in the group treated with donepezil 10 mg/day (SIB-L treatment difference 0.8, P = 0.0013; SIB[lang] treatment difference 0.8, P = 0.0009). Similar results were observed in a cohort of patients with more severe baseline disease (MMSE score 0 to 16). At baseline and week 24, correlations between the SIB-derived language scales and the ADCS-ADL-sev and CIBIC-plus were moderate, but the correlations were stronger between the language scales and the MMSE scores.

Conclusions

Patients with moderate to severe AD receiving donepezil 23 mg/day showed greater language benefits than those receiving donepezil 10 mg/day as measured by SIB-derived language assessments. Increasing the dose of donepezil to 23 mg/day may provide language benefits in patients with moderate to severe AD, for whom preservation of language abilities is especially critical.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00478205

Introduction

An estimated 5.1 million Americans over 65 years of age have Alzheimer's disease (AD), and more than half of these individuals are classified as having moderate or severe disease [1]. As disease severity increases, patients progressively lose the ability to communicate, express their needs and participate in their accustomed relationships [2-4]. In patients with more advanced disease, this often leads to an inability to sustain social relationships, express needs for medical attention and relate or respond to caregivers. Moreover, caregivers often become frustrated by difficulties in understanding and meeting patients' loved ones' needs, which can lead to further patient distress [3,5-7]. The ability to use language to communicate helps to maintain emotional connections between the patient and his or her caregiver and/or family, and loss of language ability is among the most distressing factors associated with AD [3]. Thus, treatment that can delay or even improve language abilities is an important focus of AD therapy.

Effective treatment of the loss of language abilities presupposes the availability of reliable instruments for evaluating such function. Commonly used tools such as the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale, which is primarily a clinical trial measure developed to track the progression of AD symptoms [8], and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [9], which is used in both clinical trials and clinical practice, are valid and reliable measures of cognition and change in cognitive function in less advanced stages of AD. However, when patients progress into the moderate to severe stages of AD, these common tools are subject to a "floor effect," as they may become relatively insensitive to changes in disease severity [10]. The Severe Impairment Battery (SIB), originally developed more than 20 years ago, was designed to assess cognition and changes in cognitive function in patients with more advanced impairment [11-14]. The SIB uses one-step conversational commands presented in conjunction with gestural cues, enhancing its utility in patients with profound impairments in communicative ability. The SIB remains a reliable and sensitive assessment tool as patients progress along the continuum of moderate to severe AD, and it is a widely used and validated measure of cognitive function in clinical trials [10,15-17].

Because of the centrality of language to cognitive function, 24 of the 51 total items and subitems in the full SIB scale assess language ability and comprise the SIB language subscale [3]. In a previous study, a principal components factor analysis of these 24 items was performed to determine which were the most relevant in assessing language function [3]. Using baseline data from patients enrolled in four placebo-controlled trials of memantine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, in moderate to severe AD (baseline MMSE score <15), 21 of the 24 items were found to have a factor loading >0.5 and were subsequently included in a new language scale, the SIB Language scale (SIB-L). Three of the twenty-four items had a factor loading <0.5 and were excluded from the SIB-L; the maximal SIB-L score is 41. A subsequent post hoc analysis of data from the same four trials, but which excluded patients who did not have language deficits at baseline, demonstrated significant differences on the SIB-L favoring active treatment over placebo, but SIB-L scores were decreased compared with baseline in both treatment arms [18].

The cholinesterase inhibitor donepezil is the most frequently prescribed medication worldwide for the symptomatic treatment of mild, moderate and severe AD [19,20]. Recently, a new dose of donepezil, a 23-mg tablet, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Herein we report the results of a post hoc analysis of data from a large, multinational, double-blind trial of donepezil 23 mg/day versus donepezil 10 mg/day performed to determine whether treatment with higher-dose donepezil is associated with benefits in language abilities in patients with moderate to severe AD. Moreover, since previous reports have indicated that cognition and function may be interrelated in patients with moderate to severe AD [21,22], we also evaluated relationships between measures of language function and other instruments used to assess AD status.

Materials and methods

Study design

Detailed methods used in the original clinical trial have been described previously [23]. In brief, this was a 24-week, double-blind, parallel group trial including 1,467 patients with moderate to severe AD (baseline MMSE scores 0 to 20 inclusive) who had been receiving a stable dose of donepezil 10 mg/day for at least three months. Patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio either to an increased donepezil dose of 23 mg/day or to continue their preexisting donepezil 10 mg/day dose. The duration of treatment was 24 weeks. Coprimary efficacy measures were change from baseline in SIB total score (cognition) and the Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input (CIBIC-plus; global function) score at week 24. The protocol and informed consent form for the original trial were approved by the independent ethics committee and institutional review board of each participating site and conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and all local regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from each participating patient, if possible, or from the patient's legal guardian or representative. If a patient was unable to provide written consent, verbal assent to participate was required, with documentation of this assent noted in the study record [23].

Scale construction

A new SIB-derived language scale, the 21-item Severe Impairment Battery-derived language scale (SIB[lang] scale), was constructed by performing a principal components factor analysis, similar to that employed in the creation of the SIB-L [3], on baseline scores of the 24-item SIB language subscale in the full intention-to-treat (ITT) population (see Additional File 1 for a listing of the 24 items in the SIB language subscale). Initial factors were selected on the basis of eigenvalues >1. Selection of items for inclusion in the SIB[lang] scale was based on a threshold of 0.5 for the single-item loading of each identified factor. Items with a factor loading <0.5 were deleted. In total, 21 of the 24 items in the SIB language subscale were identified as having a factor loading >0.5 and were included in the SIB[lang] scale. Three items were excluded because of a factor loading <0.5: free discourse, verbal comprehension and repeating the word "baby." As with the SIB-L scale, scores on the SIB[lang] scale range from 0 to 41.

Post hoc analysis population

The post hoc language analyses were performed in the full ITT population (all MMSE scores 0 to 20) and in a cohort of patients with more severe baseline disease (MMSE scores 0 to 16).

Analysis of treatment effects

Changes from baseline to week 24 in SIB-L and SIB[lang] scale scores for the 23 mg/day and 10 mg/day treatment groups were analyzed using an analysis of covariance model with terms for baseline score, country and treatment. For each end point, the least squares (LS) or adjusted mean for each treatment group was calculated, as were between-treatment differences (donepezil 23 mg/day compared with donepezil 10 mg/day) in adjusted means, 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the differences and the P values for the between-treatment differences. Summary statistics (median, mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum, maximum and number of patients with nonmissing data) at week 24 using last observation carried forward and observed cases are provided by treatment group.

Analysis of correlations between outcome measures

Relationships between SIB-L and SIB[lang] scale scores and scores on the MMSE, the Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Severity-plus caregiver input (CIBIS-plus; the baseline version of the CIBIC-plus assessment tool) and CIBIC-plus, and the severe version of the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL-sev) were examined. The ADCS-ADL-sev scale was analyzed both as a complete unit and when separated into two subscales reflecting basic and instrumental ADL abilities. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for baseline, week 24 and change from baseline scores. Because higher scores on the SIB-derived language scales, the MMSE and the ADCS-ADL-sev indicate less impairment, correlation coefficients between these measures are positive. Since higher scores on the CIBIS-plus/CIBIC-plus scales indicate greater impairment, correlation coefficients for relationships between SIB-L or SIB[lang] scores and CIBIS-plus/CIBIC-plus scores are negative.

Results

Patients

The full ITT population comprised 1,371 patients, 909 of whom received donepezil 23 mg/day and 462 of whom received donepezil 10 mg/day. Demographics and baseline disease characteristics were similar for both donepezil treatment groups (Table 1), and no meaningful differences were observed between the groups in relation to baseline scores on the SIB-derived language scales (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics in the intention-to-treat populationa

| Characteristics | Donepezil 23 mg/day | Donepezil 10 mg/day |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Number of patients | 909 | 462 |

| Mean (±SD) | 73.8 (8.48) | 73.8 (8.55) |

| Gender | ||

| Number of patients | 909 | 462 |

| Males, n (%) | 335 (36.9%) | 175 (37.9%) |

| Females, n (%) | 574 (63.1%) | 287 (62.1%) |

| MMSE | ||

| Number of patients | 908 | 462 |

| Mean (±SD) | 13.1 (4.99) | 13.1 (4.72) |

| ADCS-ADL-sev total | ||

| Number of patients | 908 | 461 |

| Mean (±SD) | 34.1 (10.88) | 34.5 (11.19) |

| SIB | ||

| Number of patients | 907 | 462 |

| Mean (±SD) | 74.2 (17.58) | 75.6 (16.28) |

| CIBIS-plus | ||

| Number of patients | 904 | 461 |

| Mean (±SD) | 4.42 (0.85) | 4.38 (0.89) |

| Concomitant memantine use | ||

| Number of patients | 909 | 462 |

| Using memantine, n (%) | 338 (37.2) | 163 (35.3) |

aMMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; ADCS-ADL-sev = Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living inventory, severe version; SIB = Severe Impairment Battery; CIBIS-plus = Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Severity-plus caregiver input; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Baseline scores on SIB-derived language scales in the ITT populationa

| MMSE score | SIB-L | SIB[lang] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil 23 mg/day | Donepezil 10 mg/day | Donepezil 23 mg/day | Donepezil 10 mg/day | |

| 0 to 20b | 32.4 ± 8.2 (n = 907) |

32.9 ± 7.7 (n = 462) |

31.4 ± 8.3 (n = 907) |

31.9 ± 7.7 (n = 462) |

| 0 to 16 | 30.5 ± 8.9 (n = 641) |

31.2 ± 8.3 (n = 331 ) |

29.5 ± 9.0 (n = 641) |

30.3 ± 8.4 (n = 331) |

aSIB = Severe Impairment Battery; ITT = intention to treat; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; SIB-L = Severe Impairment Battery-Language scale; SIB[lang] = 21-item Severe Impairment Battery-derived language scale; bfull ITT population. Data are means ± SD.

Study coprimary end points

As previously reported, the change from baseline in SIB scores at week 24 showed significant improvement in cognition associated with treatment with donepezil 23 mg/day relative to treatment with donepezil 10 mg/day (LS mean score change 2.6 versus 0.4, treatment difference 2.2; P < 0.001) [23]. Treatment difference in global function as measured by the CIBIC-plus scale numerically favored donepezil 23 mg/day but was not statistically significant.

Post hoc analysis: treatment effects

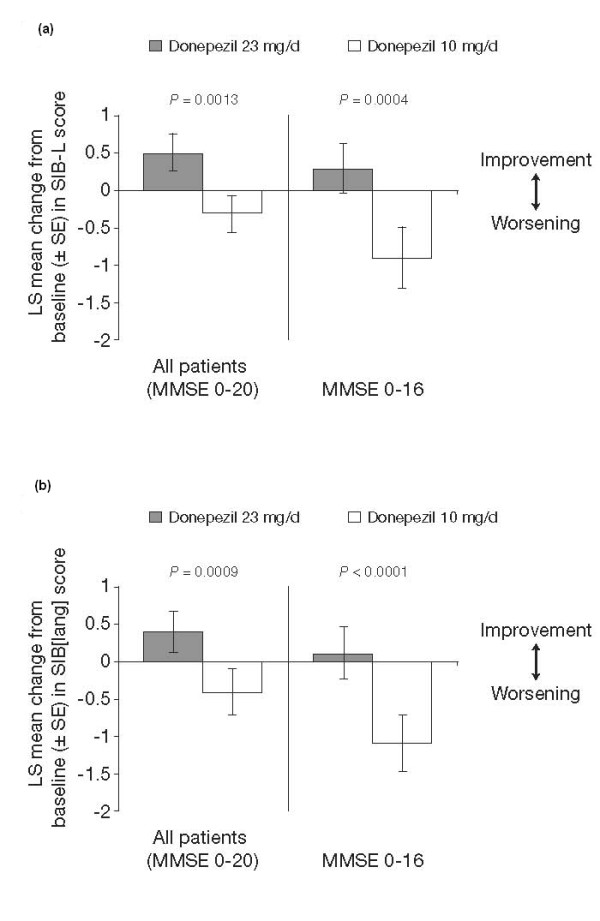

Changes in SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores from baseline to week 24 are shown in Figure 1. For both language assessments, donepezil 23 mg/day was associated with improvement in language function in the full ITT population as well as in the MMSE scale 0 to 16 score cohort. Regardless of the language assessment used, treatment with donepezil 10 mg/day was associated with a mean decline in language function in both the full ITT and MMSE scale 0 to 16 score cohort. Treatment differences between donepezil 23 mg/day and donepezil 10 mg/day were statistically significant in all analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Least squares (LS) mean change from baseline to week 24 in Severe Impairment Battery-Language scale (SIB-L) scores (A) and 21-item Severe Impairment Battery-derived language scale (SIB[lang]) scores (B). MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; SE = standard error of the mean.

Post hoc analysis: correlations

At baseline, SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores were moderately correlated with scores on the ADCS-ADL-sev (r ≈ 0.5) and CIBIS-plus (r ≈ -0.5) (Table 3). Baseline correlations between SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores and scores on the MMSE were strong (r ≈ 0.7).

Table 3.

Correlations between SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores and scores on the ADCS-ADL-sev (total, basic and instrumental), CIBIS/CIBIC-plus and MMSE (full ITT population)a

| SIB-L | SIB[lang] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD scales | Baseline | Week 24 | Change from baseline | Baseline | Week 24 | Change from baseline |

| ADCS-ADL-sev total | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.5268 | 0.1497 | 0.5250 | 0.1418 | ||

| Week 24 | 0.5820 | 0.5777 | ||||

| Change from baseline | 0.2837 | 0.2912 | ||||

| ADCS-ADL-sev basic | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.5214 | 0.1124 | 0.5193 | 0.1036 | ||

| Week 24 | 0.5669 | 0.5621 | ||||

| Change from baseline | 0.2643 | 0.2695 | ||||

| ADCS-ADL-sev instrumental | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.4745 | 0.1546 | 0.4730 | 0.1481 | ||

| Week 24 | 0.5400 | 0.5365 | ||||

| Change from baseline | 0.2369 | 0.2441 | ||||

| CIBIS-plus/CIBIC-plus | ||||||

| Baseline (CIBIS-plus) | -0.5100 | -0.1722 | -0.5117 | -0.1821 | ||

| Week 24 (CIBIC-plus) | -0.1918 | -0.1891 | ||||

| Change from baseline (CIBIC-plus) | -0.3484 | -0.3493 | ||||

| MMSE | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.7208 | 0.2205 | 0.7183 | 0.2359 | ||

| Week 24 | 0.7375 | 0.7394 | ||||

| Change from baseline | 0.3618 | 0.3517 | ||||

aSIB-L = Severe Impairment Battery-Language scale; SIB[lang] = 21-item Severe Impairment Battery-derived language scale; ADCS-ADL-sev = Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living inventory, severe version; CIBIS-plus = Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Severity-plus caregiver input; CIBIC-plus = Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; ITT = intention to treat; n values for individual correlation coefficients ranged from 1,363 to 1,371. All correlations were statistically significant (P ≤ 0.0001).

At week 24, correlations between SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores and scores on the ADCS-ADL-sev and MMSE were marginally but consistently stronger than at baseline (Table 3). In contrast, correlations between scores on the SIB-derived language scales and CIBIS-plus/CIBIC-plus scores were weaker at week 24 than at baseline.

Correlations between change from baseline in SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores and change from baseline in scores on other assessments were generally of weak to moderate strength, with the MMSE scores showing the strongest correlation (Table 3). Likewise, change from baseline in SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores showed only weak correlations with baseline assessments for the other measures.

Discussion

The already fragile relationships in the lives of patients with AD can become profoundly disrupted as patients lose the ability to communicate coherently. Attachment to caregivers and others becomes compromised, and the effect of such detachment on caregivers can be deleterious. Furthermore, it is difficult for clinicians and caregivers to render optimal care in the absence of clear input from patients regarding what they are feeling or concerned about. When language comprehension deteriorates, it is also likely to further increase caregiving stress, as patients have difficulty understanding conversation and even simple directions. Moreover, decline in language is associated with increased risk of mortality [24]. Therefore, therapy to slow or reduce the loss of language abilities has the potential to result in additional quality time for patients and caregivers alike.

In the primary study of donepezil 23 mg/day versus donepezil 10 mg/day, patients treated with donepezil 23 mg/day showed significant improvement in cognition, as measured by the SIB, compared with patients taking donepezil 10 mg/day [23]. Notably, SIB total scores at week 24 were improved relative to baseline scores in the donepezil 23 mg/day group, indicating that there was no measurable decline in cognition over the six months of treatment. In this post hoc analysis, we found that treatment with donepezil 23 mg/day resulted in significant improvement in language ability compared with donepezil 10 mg/day in patients with moderate to severe AD as measured by the two SIB-derived language scales: the SIB-L, and the SIB[lang].

Since the SIB-L was derived using data from a population of patients with baseline MMSE scores <15 enrolled in studies of memantine versus placebo [3], there was a possibility that this scale would not be suitable for the measurement of language function in the current analysis, as this patient population had differing baseline characteristics and demographics. Therefore, the SIB[lang] scale was created by performing a factor analysis of baseline SIB language subscale scores in the full ITT population from the study of donepezil 23 mg/day versus donepezil 10 mg/day. As was the case in the creation of the SIB-L [3], the SIB[lang] scale comprised 21 of the 24 items in the SIB language subscale, with three items excluded. However, while the free discourse item was excluded from both scales, the other two items eliminated in the creation of the SIB[lang] scale (verbal comprehension and repeating the word "baby") were different from those excluded from the original SIB-L (forced choice naming, cup and shape identification, square). This suggests that the results of the two factor analyses were somewhat study population-driven, likely reflecting AD severity as well as cultural influences on language assessment. Nevertheless, the fact that the SIB-L and SIB[lang] scales showed equivalent performance in the current analysis demonstrates that the utility of these language scales extends beyond the specific patient populations from which they are derived.

The findings of this post hoc language analysis have important clinical implications. One is to support the assertion that language and the ability to communicate can be reliably and easily assessed in patients with moderate to severe AD using SIB-derived language scales. Of potentially greater importance is the finding that not only were substantial incremental benefits in language ability achieved with donepezil 23 mg/day treatment beyond those achieved with donepezil 10 mg/day, but also the benefits were evident in both the full study population (MMSE scores 0 to 20) and the cohort of patients with more severe baseline disease (MMSE scores 0 to 16). Indeed, in both analysis populations, the donepezil 23 mg/day treatment group showed improvements in language function above baseline performance levels after six months of treatment, whereas the donepezil 10 mg/day group showed declines in language function. This suggests that the donepezil 23 mg/day dose may help to preserve language abilities in patients as they move across the spectrum of moderate to severe AD.

Why the donepezil 23 mg/day dose should have a greater effect on language function as compared with the donepezil 10 mg/day dose was not investigated in this analysis. However, one could speculate that the observed outcomes may be due to the higher dose of donepezil providing greater enhancement of cholinergic function in regions of the brain controlling speech and language. Another hypothetical scenario is that the observed language benefits are driven in whole or in part by enhanced effects of the 23 mg/day dose on regions of the brain controlling other cognitive processes, such as attention and memory. Indeed, it is logical that attention deficits could substantially influence a patient's language ability as measured by the SIB-L and SIB[lang] scales. Moreover, there is clearly some overlap between certain aspects of language impairment, such as word-finding difficulty, and more general memory retrieval problems. Nevertheless, the items included in the SIB-L and SIB[lang] scales cover a broad range of language functions, including processes that are not highly dependent on memory, and, as such, treatment effects on memory are likely to account for a relatively small portion of the observed language improvements. Ultimately, the direct and indirect mechanisms whereby donepezil 23 mg/day provides improved language benefits over the donepezil 10 mg/day dose need to be determined in adequately designed prospective studies.

Language effects of other pharmacologic treatments for AD have varied in studies of patients with moderate to severe disease. For example, in an analysis of pooled data from four memantine trials in patients with moderate to severe AD (MMSE score <15), mean SIB-L score changes from baseline through week 24 or week 28 were significantly better for those receiving the active treatment compared with placebo, but mean SIB-L scores declined in both treatment groups [18]. Likewise, in a post hoc analysis of the specific language effects of memantine in patients with moderate to severe AD (MMSE scores 3 to 14) enrolled in six clinical trials, memantine was associated with significantly better SIB language subscale scores compared with placebo; however, scores in both groups declined from baseline to the end of the study (six months) [25]. In addition, in a cohort of patients with severe AD (MMSE scores 5 to 12) treated with the cholinesterase inhibitor galantamine for 26 weeks, mean SIB language subscale scores were numerically improved at the end point, but improvement over placebo was not statistically significant [26].

Not surprisingly, the MMSE, a measure of cognition that includes several language items, showed the strongest correlation with SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores for all relationships explored. However, correlations between the language scales and the MMSE were substantially stronger for baseline and week 24 scores (r ≈ 0.7) than for change from baseline scores (r ≈ 0.35). This suggests that cognition as measured by the MMSE is strongly related to language abilities as measured by SIB-derived language scales, but that changes in cognition on the MMSE and changes in language on the SIB language scales track differently over time. Pearson correlation coefficients also showed that baseline SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores were moderately correlated with baseline scores for the ADCS-ADL-sev and CIBIS-plus, suggesting that language abilities and functional abilities may be interrelated in the moderate to severe AD population. However, correlations for change from baseline scores were only of moderate to weak strength. As Farlow and colleagues [23] previously reported, changes in ADCS-ADL-sev scores and CIBIC-plus scores in this study were small. Coupled with the limitations of these classes of instruments, this may at least in part explain the absence of stronger correlations. It is also noteworthy that changes from baseline to week 24 in SIB-L and SIB[lang] scores were only weakly correlated with baseline scores on the ADCS-ADL-sev, CIBIS-plus and MMSE. This suggests that there is little relationship between baseline functional or cognitive status and treatment-mediated changes in language abilities; thus, patients with AD may achieve meaningful language benefits with treatment, irrespective of the degree of functional or cognitive impairment. Since the correlation findings are from a post hoc analysis, they will need to be corroborated in prospective studies.

Conclusions

The results of this analysis suggest that donepezil 23 mg/day may result in improvements in the critical factor of language in advanced AD as measured by SIB-derived language scales. These findings indicate that increasing the dose of donepezil to 23 mg/day may provide language benefits in patients with moderate to severe AD, for whom preservation of language abilities is especially critical. Supporting communication in patients with a progressive disease such as AD may have the potential, even in advanced stages of AD, to improve patients' quality of life and reduce the burden of AD experienced by caregivers.

Abbreviations

AD: Alzheimer's disease; ADCS-ADL-sev: Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living inventory; CIBIC-plus: Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input; CIBIS-plus: Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Severity-plus caregiver input; ITT: intention to treat; LOCF: last observation carried forward; LS: least squares; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; SD: standard deviation; SIB: Severe Impairment Battery; SIB-L: Severe Impairment Battery-Language scale; SIB[lang]: 21-item Severe Impairment Battery-derived language scale.

Competing interests

The analyses described in this article derive from a phase III clinical study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00478205) that was sponsored by Eisai Inc. Editorial assistance was provided by PAREXEL Inc. and was funded by Eisai Inc. and Pfizer Inc. The article-processing charge was financed by Eisai Inc. and Pfizer Inc. SHF has served as a paid scientific consultant to Pfizer Inc related to donepezil and several investigational compounds (≤$10,000/year; there was no payment for participation in this article). His institution has received grant/contract support from Pfizer Inc for the conduct of clinical trials of dementia and to support educational programs. He has also served as a scientific consultant to other companies marketing or developing drugs for cognition, including Lundbeck, Elan, Janssen AI, Eli Lilly, Merz, Novartis, Toyama, Bellus Health, Bayer Healthcare, Accera, Otsuka, Sunovion, Symphony Icon and Torrey Pines, and his institution has received grant/contract support for clinical trials from Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Janssen AI, Baxter and Bristol-Myers Squibb. He also has stock options from Accera, Intellect Neurosciences, MedAvante and Symphony Icon. FAS has no financial competing interests to report. He has served on a Data Safety Monitoring Committee for Pfizer Inc for which the University of Kentucky received reimbursement (<$4,000). JS has been paid as a consultant to Eisai Inc., Pfizer Inc, Forest Pharmaceuticals and Novartis. JS currently receives royalties from the original Severe Impairment Battery on which this reduced scale is based. SR is an ex-employee of Eisai Inc. JM is an employee of Pfizer Inc. YS is an employee of Eisai Inc. YX was an employee of Pfizer Inc.

Authors' contributions

SHF, FAS, SR and JM helped to conceive and design the described analyses, participated in the data analysis and assisted in the drafting, editing and interpretation of the manuscript. JS developed the original Severe Impairment Battery scale, helped to conceive and design the described analyses, participated in the data analysis and assisted in the drafting, editing and interpretation of the manuscript. YS and YX assisted in the statistical planning and performance of the post hoc analyses and assisted in the drafting, editing and interpretation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Items in the SIB Language Subscale. A table listing the 24 items in the Severe Impairment Battery (SIB) language subscale.

Contributor Information

Steven H Ferris, Email: Steven.Ferris@nyumc.org.

Frederick A Schmitt, Email: fascom@uky.edu.

Judith Saxton, Email: saxtonja@upmc.edu.

Sharon Richardson, Email: Sharon_Richardson@eisai.com.

Joan Mackell, Email: Joan.Mackell@pfizer.com.

Yijun Sun, Email: Yijun_Sun@eisai.com.

Yikang Xu, Email: Yikang.Xu@pfizer.com.

Acknowledgements

During the development of this article, editorial assistance was provided by Richard Daniel, PhD, at PAREXEL Inc., and the study was funded by Eisai Inc. and Pfizer Inc. The authors note Dr Yikang Xu's valued contributions to the analyses described herein and mourn the loss of their esteemed colleague.

References

- Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair M, Marczinski CA, Davis-Faroque N, Kertesz A. A longitudinal study of language decline in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:237–245. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris S, Ihl R, Robert P, Winblad B, Gatz G, Tennigkeit F, Gauthier S. Severe Impairment Battery Language scale: a language-assessment tool for Alzheimer's disease patients. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.04.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR, Phillips LH. Verbal fluency performance in dementia of the Alzheimer's type: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:1212–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendryx-Bedalov PM. Alzheimer's dementia: coping with communication decline. J Gerontol Nurs. 2000;26:20–24. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20000801-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potkins D, Myint P, Bannister C, Tadros G, Chithramohan R, Swann A, O'Brien J, Fossey J, George E, Ballard C, Margallo-Lana M. Language impairment in dementia: impact on symptoms and care needs in residential homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:1002–1006. doi: 10.1002/gps.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savundranayagam MY, Hummert ML, Montgomery RJ. Investigating the effects of communication problems on caregiver burden. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:S48–S55. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.1.s48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356–1364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt FA, Cragar D, Ashford JW, Reisberg B, Ferris S, Möbius HJ, Stöffler A. Measuring cognition in advanced Alzheimer's disease for clinical trials. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2002;62:135–148. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6139-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panisset M, Roudier M, Saxton J, Boller F. Severe Impairment Battery: a neuropsychological test for severely demented patients. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:41–45. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540130067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton J, Kastango KB, Hugonot-Diener L, Boller F, Verny M, Sarles CE, Girgis RR, Devouche E, Mecocci P, Pollock BG, DeKosky ST. Development of a short form of the Severe Impairment Battery. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:999–1005. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.11.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt FA, Ashford W, Ernesto C, Saxton J, Schneider LS, Clark CM, Ferris SH, Mackell JA, Schafer K, Thal LJ. The Severe Impairment Battery: concurrent validity and the assessment of longitudinal change in Alzheimer's disease. The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 2):S51–S56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton J, McGonigle-Gibson KL, Swihart AA, Miller VJ, Boller F. Assessment of the severely impaired patient: description and validation of a new neuropsychological test battery. Psychol Assess. 1990;2:298–303. [Google Scholar]

- Emre M, Mecocci P, Stender K. Pooled analyses on cognitive effects of memantine in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;14:193–199. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-14207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt FA, Wichems CH. A systematic review of assessment and treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8:158–159. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v08n0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Black SE, Homma A, Schwam E, Moline M, Xu Y, Perdomo C, Swartz J, Albert K. Donepezil treatment in severe Alzheimer's disease: a pooled analysis of three clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:2577–2587. doi: 10.1185/03007990903236731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris S, Ihl R, Robert P, Winblad B, Gatz G, Tennigkeit F, Gauthier S. Treatment effects of memantine on language in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease patients. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.05.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARICEPT donepezil hydrochloride tablets. http://us.eisai.com/product.asp?ID=168

- Mucha L, Shaohung S, Cuffel B, McRae T, Mark TL, Del Valle M. Comparison of cholinesterase inhibitor utilization patterns and associated health care costs in Alzheimer's disease. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14:451–461. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2008.14.5.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman HH, Van Baelen B, Kavanagh SM, Torfs KE. Cognition, function, and caregiving time patterns in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer disease: a 12-month analysis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19:29–36. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000157065.43282.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pélissier C, Roudier M, Boller F. Factorial validation of the Severe Impairment Battery for patients with Alzheimer's disease: a pilot study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;13:95–100. doi: 10.1159/000048640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow MR, Salloway S, Tariot PN, Yardley J, Moline ML, Wang Q, Brand-Schieber E, Zou H, Hsu T, Satlin A. Effectiveness and tolerability of high-dose (23 mg/d) versus standard-dose (10 mg/d) donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind study. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1234–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino S, Scarmeas N, Albert SM, Stern Y. Verbal fluency predicts mortality in Alzheimer disease. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2006;19:123–129. doi: 10.1097/01.wnn.0000213912.87642.3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecocci P, Bladström A, Stender K. Effects of memantine on cognition in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease: post-hoc analyses of ADAS-cog and SIB total and single-item scores from six randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:532–538. doi: 10.1002/gps.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A, Bernabei R, Bullock R, Cruz Jentoft AJ, Frölich L, Hock C, Raivio M, Triau E, Vandewoude M, Wimo A, Came E, Van Baelen B, Hammond GL, van Oene JC, Schwalen S. Safety and efficacy of galantamine (Reminyl) in severe Alzheimer's disease (the SERAD study): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:39–47. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Items in the SIB Language Subscale. A table listing the 24 items in the Severe Impairment Battery (SIB) language subscale.