Abstract

Significant advances in our understanding of the genetic defects and the pathogenesis of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) have been achieved in the last several years. The information gathered tremendously helps us in designing molecular targeted therapies for this otherwise fatal disease. Various approaches are being investigated to target defective pathways/molecules in this disease. However, effective therapy is still lacking. Development of specific target-based drugs for JMML remains a big challenge and represents a promising direction in this field.

1. Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia (JMML) and Current Clinical Standard of Care

Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) is a rare hematologic malignancy of early childhood with high mortality. It represents 2% to 3% of all pediatric leukemias [1, 2], and its incidence is approximately 0.6 per million children per year [3]. Clinically, patients often present with pallor, failure to thrive, decreased appetite, irritability, dry cough, tachypnea, skin rashes, and diarrhea and are found to have lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly on examination [4–8]. JMML is characterized by leukocytosis with prominent monocytosis, thrombocytopenia, elevation of fetal hemoglobin (HbF), and hypersensitivity of hematopoietic progenitors to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [4–8].

Prior to the revision in 2008, JMML was diagnosed based on the following criteria: presence of peripheral blood monocytosis (>1000/μL); less than 20% blasts in the bone marrow; absence of Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome or BCR-ABL fusion gene AND at least two of the following criteria: increased HbF levels; presence of immature myeloid precursors in the peripheral blood; white blood cell count >10,000/μL; GM-CSF hypersensitivity of myeloid progenitors in vitro [5, 9]. In 2008, the JMML diagnostic criteria were revised to account for the molecular genetic abnormalities that were identified in this disease [5].

The natural course of JMML is rapidly fatal with 80% of patients surviving less than three years [10]. Low platelet count, age at diagnosis older than 2 years, and high HbF percentage have been shown to correlate with poor outcome [11]. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is currently the only curative treatment for JMML, but controversy exists in identifying the patients that need to proceed to transplant immediately versus those that can be observed for a longer time. Patients with Noonan syndrome often develop a JMML-like myeloproliferative disorder that may resolve spontaneously within one year of presentation [12]. While awaiting transplant, most patients receive chemotherapy, and most clinicians will use cytarabine-based acute myeloid leukemia-like therapy [10, 13]. Identification of gene mutations in the RAS-MAPK pathway has increased interest in development of drugs that can specifically affect molecular targets. For more detailed review of genetic mutations in JMML and approaches to therapy, please refer to Dr. Loh's recent article [14]. Here, we shall proceed to briefly discuss molecular defects in JMML with focus on potential drug targets.

2. Identification of Genetic Mutations in JMML

The molecular defects in JMML result in deregulated signaling through the RAS pathway [15–17]. These mutations are mutually exclusive which highlights the major functional role of the RAS pathway activation in JMML pathophysiology and disease progression. The specific genes implicated in JMML are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of genetic mutations in JMML.

| Gene | Site of mutation | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| PTPN11 | E76K, D61Y, D61V, E69K, A72T, A72V, E76V/G/A, | 35% |

| RAS | ||

| NRAS | Codons 12 and 13 | 25% |

| KRAS | Codon 13 | |

| HRAS | No mutation in codons 12, 13, and 61 was found | |

| NF1 | Loss of wild-type NF1 allele | 11–15% |

| CBL | Codons 371, 380, 381, 384, 396, 398, 404, and 408. | 17% |

| Splice sites 1227, 1228, and 1096 |

2.1. PTPN11

Somatic mutations within PTPN11, which encodes protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, have been found in 35% of JMML patients [18, 19]. PTPN11 mutations were also associated with poor prognosis for survival. Mutation in PTPN11 was the only unfavorable factor for relapse after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [20]. SHP-2 contains 2 Src homology 2 domains (N-SH2 and C-SH2) at the amino terminus and a phosphatase domain at the carboxy terminus [21–25]. It is involved in a variety of signaling pathways, especially the RAS/MAPK/ERK pathway [26–28]. SHP-2 is normally self-inhibited by hydrogen bonding of the backside of the N-SH2 domain loop to the deep pocket of the PTP domain [29, 30]. The self-inhibition leads to occlusion of the phosphatase catalytic site and a distortion of the pY-binding site of N-SH2. PTPN11 mutations found in JMML are mainly localized in the N-SH2 domain. These mutations result in amino acid changes at the interface formed between N-SH2 and PTP domains, disrupting the inhibitory intramolecular interaction, leading to hyperactivation of SHP-2 catalytic activity [18, 31]. In addition, disease mutations enhance the binding of mutant SHP-2 to signaling partners [32–34]. Recent studies have shown that PTPN11 gain-of-function mutations induce cytokine hypersensitivity in myeloid progenitors [16, 34, 35] and myeloproliferative disease with some similarity to JMML in mice [32, 36–38], establishing the causal role of PTPN11 mutations in the pathogenesis of JMML. It is evident that increased signal transduction along SHP-2's pathways leads to aberrant hematopoietic cell proliferation and differentiation. SHP-2 may, thus, be an ideal target of mechanism-based therapeutics for this disease.

2.2. RAS

The RAS subfamily includes three members: HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS. Twenty-five percent of JMML patients were found to have a somatic NRAS or KRAS point mutation [20, 39]. Flotho et al. analyzed 36 children with JMML. RAS mutations were detected in 6 cases. Two children had a mutation in codon 12 of NRAS, 3 children in codon 13 of NRAS, and 1 child in codon 13 of KRAS. No mutation in HRAS codons 12, 13, or 61 was found [40]. De Filippi et al. reported a 38G > A (G13D) mutation in the NRAS gene in all types of cells checked in a male infant who was diagnosed with JMML [41]. This case suggests that constitutively active mutations of NRAS may be responsible for the development of JMML in children [41].

2.3. NF1

In 1994, Shannon et al. demonstrated loss of the wild-type NF1 allele in the diseased bone marrow of children with JMML affected by neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) [42]. The protein product of NF1, neurofibromin (NF1), contains a GTPase-activating protein- (GAP-) related domain. It inhibits RAS signaling by increasing the intrinsic GTPase activity of RAS-GTP and, thus, the generation of inactive RAS-GDP [43]. Eleven percent of JMML patients have constitutive NF1 [44] and 15% of the JMML patients without clinical signs of NF1 [39, 45]. A mitotic recombination event in JMML-initiating cells led to 17q uniparental disomy with homozygous loss of normal NF1, providing confirmatory evidence that the NF1 gene is crucial for the increased incidence of JMML in NF1 patients [44]. In addition, children (but not adults) with NF1 show a 200- to 500-fold increase in the incidence of de novo malignant myeloid disorders, particularly JMML [46].

2.4. CBL

The Casitas B-cell lymphoma (CBL, c-CBL) protein is a member of the CBL family of E3 ubiquitin ligases. Loh et al. first reported that c-CBL mutations were detected in 27 of 159 JMML samples, and 13 of these mutations alter codon Y371 [47]. The same c-CBL mutation was also found in another study with a smaller cohort of JMML patients [48]. A recent study screened CBL mutations in 65 patients with JMML [49]. A homozygous mutation of CBL was found in leukemic cells of 4/65 (6%) patients. A heterozygous germ line CBL Y371H substitution was found in each of them and was inherited from the father in one patient. The germ line mutation represents the first hit, with somatic loss of heterozygosity being the second hit positively selected in JMML cells [49]. Individuals with germ line CBL mutations are at increased risk of developing JMML, which might follow an aggressive clinical course or resolve without treatment [50].

In addition to PTPN11, RAS, and NF1 mutations, other mutations have been reported to occur rarely in JMML, such as additional sex combs like 1 (AXSL1) [51] and fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) [52]. Mutations in let-7 or in binding sites of let-7 mRNA targets lead to an upregulation of RAS genes in JMML. It is possible that other microRNAs known to bind to NRAS- or KRAS-UTR, or other let-7 family mi-RNAs may play a role in the development of JMML [53]. However, mutations which are reported to play a major role in myeloproliferative neoplasms, such as ten-eleven translocation-2 (TET2), runt-related transcription factor 1 isoform (RUNX1), janus kinase 2 (JAK2) V617F [54], and Soc-2 suppressor of clear homolog SHOC2 [55] are not involved in JMML.

3. Chromosomal Aberrations

Some chromosome abnormalities were found in JMML. The most common chromosome abnormalities in JMML patients are monosomy 7 or deletion 7q (-7/del(7q)) [56]. In addition, there are some case reports for other chromosomal aberrations. For example, a 11-month-old boy with JMML had deletion 5q as the sole clonal chromosome abnormality [57]. Another JMML patient had a chromosomal translocation at t(1;5) [58]. Also, leukemic cells in a JMML patient harbored a 46,XX,der(12)t(3;12) (q21~22;p13.33) karyotype and subsequently developed partial trisomy of 3q [59]. However, at this time specific genes associated with these breakpoints are not yet identified, and; thus, the relevance of these chromosomal aberrations remains to be determined.

4. Recent Experimental Therapy for JMML

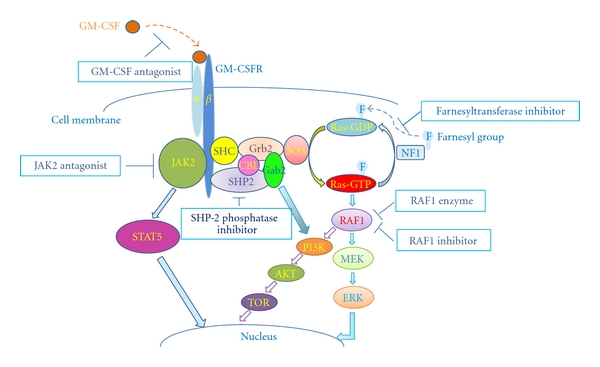

The recent focus in JMML has concentrated on using the information gained from knowledge of these molecular defects in order to design targeted drug therapy. Animal models, especially mouse models of the disease, are commonly used to test molecularly targeted agents. Since RAS hyperactivation is very important in the pathophysiology of JMML, agents designed to decrease RAS activity are being evaluated. There are numerous approaches that have been tested to target this pathway (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

4.1. RAF1 Enzyme

RAF1 is a MAP kinase (MAP3K) that functions downstream of the RAS subfamily of membrane-associated GTPases to which it binds directly and plays an important role in the MAPK/ERK signal transduction pathway as part of a protein kinase cascade. A DNA enzyme designed to specifically cleave mRNA for RAF1, named RAF1 enzyme, was tested on JMML cells cultured both in vitro and in a xenograft model of JMML. When immunodeficient mice engrafted with JMML cells were treated continuously with this enzyme for 4 weeks, JMML cell numbers in the recipient murine bone marrows were profoundly reduced. No effect of the enzyme on the proliferation of normal bone marrow cells was found in vitro, indicating its specificity and potential safety [60].

4.2. RAF1 Inhibitor: BAY 43-9006

BAY 43-9006 is a low-molecular-weight agent that inhibits both the wild-type BRAF and the activated V599E mutant BRAF by binding at the active site of the kinase [61]. BAY 43-9006 can significantly inhibit tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner and has demonstrated oral in vivo activity in three human tumor xenograft models with mutant KRAS genes (HCT116, MiaPaca-2, H460) and one human tumor xenograft with a wild-type KRAS but exhibiting overexpression of growth factor receptors for epidermal growth factor (EGF) and HER 2 (SKOV-3) [62]. Based on these findings, a phase II window clinical trial is under development to evaluate response rate and acute toxicity to JMML patients [5].

4.3. Farnesyltransferase Inhibitor (FTI)

RAS is first activated at the cell membrane via the addition of a farnesyl group to the newly translated protein. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) can prevent RAS translocation to the plasma membrane, thus, leading to downregulation of RAS-activated cellular pathways, so its competitive inhibitors have been developed as a novel class of anticancer therapeutics. L-744,832 is one such farnesyltransferase inhibitor. It can inhibit HRAS prenylation in cell lines and in primary hematopoietic cells, abolish the in vitro growth of myeloid progenitor colonies in response to GM-CSF, and increase the amount of unprocessed HRAS in bone marrow cells. However, FTIs had no detectable effect on NRAS, and the mouse model with JMML features created by transplantation of Nf1−/− fetal liver cells did not respond to L-744,832 treatment [63]. L-739,749, another kind of FTI, also has significant growth inhibitory effects in vitro, indicating a potential treatment for JMML [64]. Unfortunately, FTIs have modest to little activity in clinical trials when used as a single agent to treat cancers, yet recent studies show that when combined with other inhibitors, such as AKT inhibitors, FTIs do show a therapeutic potential in some cancer models [65, 66].

4.4. SHP-2 Phosphatase Inhibitor

The direct connection between activating mutations in PTPN11 and JMML indicates that SHP-2 may be a useful target for mechanism-based therapeutics for this disease. It is very important to develop selective SHP-2 inhibitors. The availability of SHP-2-specific inhibitors could lead to the development of new drugs that would ultimately serve as treatments for JMML. However, development of selective SHP-2 inhibitors has been challenging as the catalytic site of SHP-2 shares a high homology with those of other tyrosine phosphatases, especially SHP-1 that plays a negative role in cytokine signaling in contrast to SHP-2 phosphatase [26–28]. Several groups have attempted to identify low molecular weight inhibitors for SHP-2 phosphatase using various approaches [67–70]. However, the inhibitors identified to date either show low or no selectivity between SHP-2 and highly related SHP-1 phosphatase. Furthermore, therapeutic effects of these inhibitors in mouse models or human JMML samples have yet to be determined. More efforts are still needed to advance this line of research.

4.5. GM-CSF Antagonist: E21R

GM-CSF markedly promotes proliferation and survival of JMML cells and, thus, contributes to the aggressive nature of this malignancy [71]. Iversen et al. developed a GM-CSF analogue (E21R) that carries a single point mutation at position 21 in which glutamic acid is substituted for arginine [72]. It can effectively antagonize GM-CSF in binding experiments and in functional assays. They administrated E21R or isotonic saline to SCID/NOD mice transplanted by JMML cells or normal bone marrow cells and found that E21R reduced growth of JMML cell load in the mouse bone marrow [8]. As TNFα may increase the production of GM-CSF [71], E21R also synergizes with anti-TNFα monoclonal antibody (MoAb) cA2 in suppressing JMML cell growth. Remarkably, E21R preferentially eliminated leukemic cells [8]. These data suggest that E21R may have a therapeutic potential in JMML.

4.6. Inhibition of Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is essential for growth and metastasis of solid tumors and probably also for hematological malignancies. Endostatin and PI-88, two kinds of angiogenic inhibitors, were used to treat JMML xenograft mice and resulted in a reduction of about 95% of the malignant cell load. Furthermore, it was evident that neither endostatin nor PI-88 interfered with the engraftment of normal cells [73].

4.7. STAT5 Activation by the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK Pathway in JMML-Biomarker and Potential Therapeutic Target

In addition to activation of the RAS pathway in JMML, there are several studies that have also shown enhanced signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) activation downstream of activated RAS. In a KRAS G12D mouse model, STAT5 activation was also associated with ERK and S6K phosphorylation [74]. KRAS also led to hyper-active STAT5, AKT, and ERK pathways [75]. Furthermore, NRAS caused an adult CMML-like phenotype characterized by ERK and STAT5 activation via a GM-CSF-dependent induction mechanism [76]. In patient samples, Kotecha et al. [77] elegantly showed that both ERK and STAT5 activation are associated with human JMML, but, interestingly, it was the phosphorylated STAT5 that was prognostic in these patients, suggesting that effective suppression of STAT5 will also be an important biomarker in JMML-oriented targeted therapies. Therefore, monitoring pSTAT5 by phospho-flow cytometry shows promise for clinical application. Additionally, STAT5 can partner with the adapter protein GAB2 to provoke activation of the PI3-kinase pathway [78]. Interestingly, GAB2 is also a major partner of oncogenic SHP-2 with gain-of-function mutation D61G and is responsible for a significant contribution to the myeloproliferative disease phenotype in mice [38].

5. Discussions and Perspectives

The clinical therapy of JMML has significantly improved over the last 20 years. However, the low incidence of the disease has limited the capacity to perform large-scale pathophysiological studies and testing newer therapeutic strategies. JMML is a disease that only occurs in children, and drug dosage modifications are needed in children as compared to adults. All these factors limit the development of JMML treatment to some extent. Specific inhibitors for the molecular targets identified in this disease are still lacking.

Molecular mechanisms of JMML have been elucidated in almost 85% of patients, but it is also true that a few JMML patients with Noonan syndrome can spontaneously recover without intervention [79, 80]. This means that we do not completely understand this disease, and there is much more to learn. It is indeed promising that there have been some novel agents evaluated in investigational phase II trials of JMML patients [81, 82], and there is legitimate hope that the knowledge we have gained about JMML will soon translate into more efficacious treatment modalities. Scientists and clinicians should continue to study molecular defects in JMML in a concerted effort to define novel therapeutic targets and to develop effective, less toxic, therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants HL068212 and HL095657 (to C.-K. Q.), DK059380 (to K. D. Bunting), Cure Childhood Cancer Foundation (to K. D. Bunting and H. Sabnis), Rally Foundation for Childhood Cancer Research (to K. D. Bunting), and the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center Cancer Stem Cell Pilot Grant (to C.-K. Qu). X. Liu and H. Sabnis contributed equally to this paper.

References

- 1.Freedman MH, Estrov Z, Chan HSL. Juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia. American Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 1988;10(3):261–267. doi: 10.1097/00043426-198823000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niemeyer CM, Arico M, Basso G, et al. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in childhood: a retrospective analysis of 110 cases. European Working Group on Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Childhood (EWOG-MDS) Blood. 1997;89(10):3534–3543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manabe A, Okamura J, Yumura-Yagi K, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for 27 children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia diagnosed based on the criteria of the international JMML working group. Leukemia. 2002;16(4):645–649. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castro-Malaspina H, Schaison G, Passe S. Subacute and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in children (juvenile CML). Clinical and hematologic observations and identification of prognostic factors. Cancer. 1984;54(4):675–686. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1984)54:4<675::aid-cncr2820540415>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan RJ, Cooper T, Kratz CP, Weiss B, Loh ML. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: a report from the 2nd International JMML Symposium. Leukemia Research. 2009;33(3):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emanuel PD. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22(7):1335–1342. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emanuel PD. Myelodysplasia and myeloproliferative disorders in childhood: an update. The British Journal of Haematology. 1999;105(4):852–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iversen PO, Lewis ID, Turczynowicz S, et al. Inhibition of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor prevents dissemination and induces remission of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia in engrafted immunodeficient mice. Blood. 1997;90(12):4910–4917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura Y, Sugita Y, Seki R, et al. Infant juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) with rapid infiltration of multiple organs. Pathology International. 2010;60(4):333–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2010.02517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loh ML. Childhood myelodysplastic syndrome: focus on the approach to diagnosis and treatment of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2010;2010:357–362. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Passmore SJ, Chessells JM, Kempski H, Hann IM, Brownbill PA, Stiller CA. Paediatric myelodysplastic syndromes and juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia in the UK: a population-based study of incidence and survival. The British Journal of Haematology. 2003;121(5):758–767. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kratz CP, Niemeyer CM, Castleberry RP, et al. The mutational spectrum of PTPN11 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and Noonan syndrome/myeloproliferative disease. Blood. 2005;106(6):2183–2185. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Locatelli F, Nöllke P, Zecca M, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML): results of the EWOG-MDS/EBMT trial. Blood. 2005;105(1):410–419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loh ML. Recent advances in the pathogenesis and treatment of juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia. The British Journal of Haematology. 2011;152(6):677–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emanuel PD, Bates LJ, Castleberry RP, Gualtieri RJ, Zuckerman KS. Selective hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by juvenile chronic myeloid leukemia hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1991;77(5):925–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan RJ, Leedy MB, Munugalavadla V, et al. Human somatic PTPN11 mutations induce hematopoietic-cell hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 2005;105(9):3737–3742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flotho C, Kratz C, Niemeyer CM. Targetting RAS signalling pathways in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Current Drug Targets. 2007;8(6):715–725. doi: 10.2174/138945007780830773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tartaglia M, Niemeyer CM, Fragale A, et al. Somatic mutations in PTPN11 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia. Nature Genetics. 2003;34(2):148–150. doi: 10.1038/ng1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loh ML, Reynolds MG, Vattikuti S, et al. PTPN11 mutations in pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results from the Children’s Cancer Group. Leukemia. 2004;18(11):1831–1834. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida N, Yagasaki H, Xu Y, et al. Correlation of clinical features with the mutational status of GM-CSF signaling pathway-related genes in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Pediatric Research. 2009;65(3):334–340. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181961d2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adachi M, Sekiya M, Miyachi T, et al. Molecular cloning of a novel protein-tyrosine phosphatase SH-PTP3 with sequence similarity to the src-homology region 2. FEBS Letters. 1992;314(3):335–339. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81500-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad S, Banville D, Zhao Z, Fischer EH, Shen SH. A widely expressed human protein-tyrosine phosphatase containing src homology 2 domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(6):2197–2201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng GS, Hui CC, Pawson T. SH2-containing phosphotyrosine phosphatase as a target of protein-tyrosine kinases. Science. 1993;259(5101):1607–1611. doi: 10.1126/science.8096088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman RM, Jr., Plutzky J, Neel BG. Identification of a human src homology 2-containing protein-tyrosine-phosphatase: a putative homolog of Drosophila corkscrew. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(23):11239–11243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogel W, Lammers R, Huang J, Ullrich A. Activation of a phosphotyrosine phosphatase by tyrosine phosphorylation. Science. 1993;259(5101):1611–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.7681217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neel BG, Gu H, Pao L. The ’Shp’ing news: SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatases in cell signaling. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2003;28(6):284–293. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tonks NK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: from genes, to function, to disease. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2006;7(11):833–846. doi: 10.1038/nrm2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu D, Qu CK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in the JAK/STAT pathway. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2008;13(13):4925–4932. doi: 10.2741/3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eck MJ, Pluskeyt S, Trüb T, Harrison SC, Shoelson SE. Spatial constraints on the recognition of phosphoproteins by the tandem SH2 domains of the phosphatase SH-PTP2. Nature. 1996;379(6562):277–280. doi: 10.1038/379277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hof P, Pluskey S, Dhe-Paganon S, Eck MJ, Shoelson SE. Crystal structure of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2. Cell. 1998;92(4):441–450. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80938-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keilhack H, David FS, McGregor M, Cantley LC, Neel BG. Diverse biochemical properties of Shp2 mutants: implications for disease phenotypes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(35):30984–30993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504699200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Araki T, Mohi MG, Ismat FA, et al. Mouse model of Noonan syndrome reveals cell type- and gene dosage-dependent effects of Ptpn11 mutation. Nature Medicine. 2004;10(8):849–857. doi: 10.1038/nm1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fragale A, Tartaglia M, Wu J, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome-associated SHP2/PTPN11 mutants cause EGF-dependent prolonged GAB1 binding and sustained ERK2/MAPK1 activation. Human Mutation. 2004;23(3):267–277. doi: 10.1002/humu.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu WM, Daino H, Chen J, Bunting KD, Qu CK. Effects of a leukemia-associated gain-of-function mutation of SHP-2 phosphatase on interleukin-3 signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(9):5426–5434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schubbert S, Lieuw K, Rowe SL, et al. Functional analysis of leukemia-associated PTPN11 mutations in primary hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2005;106(1):311–317. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan G, Kalaitzidis D, Usenko T, et al. Leukemogenic Ptpn11 causes fatal myeloproliferative disorder via cell-autonomous effects on multiple stages of hematopoiesis. Blood. 2009;113(18):4414–4424. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-182626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohi MG, Williams IR, Dearolf CR, et al. Prognostic, therapeutic, and mechanistic implications of a mouse model of leukemia evoked by Shp2 (PTPN11) mutations. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(2):179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu D, Wang S, Yu WM, et al. A germline gain-of-function mutation in Ptpn11 (Shp-2) phosphatase induces myeloproliferative disease by aberrant activation of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010;116(18):3611–3621. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Vries AC, Zwaan CM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Molecular basis of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2010;95(2):179–182. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.016865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flotho C, Valcamonica S, Mach-Pascual S, et al. RAS mutations and clonality analysis in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) Leukemia. 1999;13(1):32–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Filippi P, Zecca M, Lisini D, et al. Germ-line mutation of the NRAS gene may be responsible for the development of juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia. The British Journal of Haematology. 2009;147(5):706–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shannon KM, O’Connell P, Martin GA, et al. Loss of the normal NF1 allele from the bone marrow of children with type 1 neurofibromatosis and malignant myeloid disorders. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;330(9):597–601. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Theos A, Korf BR. Pathophysiology of neurofibromatosis type 1. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;144(11):842–849. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-11-200606060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flotho C, Steinemann D, Mullighan CG, et al. Genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia identifies uniparental disomy surrounding the NF1 locus in cases associated with neurofibromatosis but not in cases with mutant RAS or PTPN11. Oncogene. 2007;26(39):5816–5821. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Side LE, Emanuel PD, Taylor B, et al. Mutations of the NF1 gene in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia without clinical evidence of neurofibromatosis, type 1. Blood. 1998;92(1):267–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aricò M, Biondi A, Pui CH. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 1997;90(2):479–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loh ML, Sakai DS, Flotho C, et al. Mutations in CBL occur frequently in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(9):1859–1863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muramatsu H, Makishima H, Jankowska AM, et al. Mutations of an E3 ubiquitin ligase c-Cbl but not TET2 mutations are pathogenic in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(10):1969–1975. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-226340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pérez B, Mechinaud F, Galambrun C, et al. Germline mutations of the CBL gene define a new genetic syndrome with predisposition to juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2010;47(10):686–691. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.076836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Niemeyer CM, Kang MW, Shin DH, et al. Germline CBL mutations cause developmental abnormalities and predispose to juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(9):794–800. doi: 10.1038/ng.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugimoto Y, Muramatsu H, Makishima H, et al. Spectrum of molecular defects in juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia includes ASXL1 mutations. The British Journal of Haematology. 2010;150(1):83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gratias EJ, Liu YL, Meleth S, Castleberry RP, Emanuel PD. Activating FLT3 mutations are rare in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2005;44(2):142–146. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinemann D, Tauscher M, Praulich I, Niemeyer CM, Flotho C, Schlegelberger B. Mutations in the let-7 binding site—a mechanism of RAS activation in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia? Haematologica. 2010;95(9):p. 1616. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.024984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pérez B, Kosmider O, Cassinat B, et al. Genetic typing of CBL, ASXL1, RUNX1, TET2 and JAK2 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia reveals a genetic profile distinct from chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. The British Journal of Haematology. 2010;151(5):460–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flotho C, Batz C, Hasle H, et al. Mutational analysis of SHOC2, a novel gene for Noonan-like syndrome, in JMML. Blood. 2010;115(4):p. 913. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luna-Fineman S, Shannon KM, Atwater SK, et al. Myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative disorders of childhood: a study of 167 patients. Blood. 1999;93(2):459–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meck JM, Otani-Rosa JA, Neuberg RW, Welsh JA, Mowrey PN, Meloni-Ehrig AM. A rare finding of deletion 5q in a child with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2009;195(2):192–194. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grainger JD, Will AM, Stevens RF. Cultured autografting for juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia. The British Journal of Haematology. 2002;117(2):477–479. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tosi S, Mosna G, Cazzaniga G, et al. Unbalanced t(3;12) in a case of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) results in partial trisomy of 3q as defined by FISH. Leukemia. 1997;11(9):1465–1468. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iversen PO, Emanuel PD, Sioud M. Targeting Raf-1 gene expression by a DNA enzyme inhibits juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia cell growth. Blood. 2002;99(11):4147–4153. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson N, Lyons J. Recent progress in targeting the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway with inhibitors in cancer drug discovery. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2005;5(4):350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lyons JF, Wilhelm S, Hibner B, Bollag G. Discovery of a novel Raf kinase inhibitor. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2001;8(3):219–225. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mahgoub N, Taylor BR, Gratiot M, et al. In vitro and in vivo effects of a farnesyltransferase inhibitor on Nf1-deficient hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1999;94(7):2469–2476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Emanuel PD, Snyder RC, Wiley T, Gopurala B, Castleberry RP. Inhibition of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia cell growth in vitro by farnesyltransferase inhibitors. Blood. 2000;95(2):639–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Balasis ME, Forinash KD, Chen YA, et al. Combination of farnesyltransferase and Akt inhibitors is synergistic in breast cancer cells and causes significant breast tumor regression in ErbB2 transgenic mice. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(9):2852–2862. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lancet JE, Duong VH, Winton EF, et al. A phase I clinical-pharmacodynamic study of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor tipifarnib in combination with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in advanced acute leukemias. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(5):1140–1146. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen L, Sung SS, Yip MLR, et al. Discovery of a novel Shp2 protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor. Molecular Pharmacology. 2006;70(2):562–570. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu WM, Guvench O, MacKerell AD, Qu CK. Identification of small molecular weight inhibitors of Src homology 2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP-2) via in silico database screening combined with experimental assay. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;51(23):7396–7404. doi: 10.1021/jm800229d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hellmuth K, Grosskopf S, Ching TL, et al. Specific inhibitors of the protein tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 identified by high-throughput docking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(20):7275–7280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710468105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang X, He Y, Liu S, et al. Salicylic acid based small molecule inhibitor for the oncogenic src homology-2 domain containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2 (SHP2) Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;53(6):2482–2493. doi: 10.1021/jm901645u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Freedman MH, Cohen A, Grunberger T, et al. Central role of tumour necrosis factor, GM-CSF, and interleukin 1 in the pathogenesis of juvenile chronic myelogenous leukaemia. The British Journal of Haematology. 1992;80(1):40–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb06398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iversen PO, Rodwell RL, Pitcher L, Taylor KM, Lopez AF. Inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemic cells by the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor analogue E21R. Blood. 1996;88(7):2634–2639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iversen PO, Sorensen DR, Benestad HB. Inhibitors of angiogenesis selectively reduce the malignant cell load in rodent models of human myeloid leukemias. Leukemia. 2002;16(3):376–381. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Meter ME, Díaz-Flores E, Archard JA, et al. K-RasG12D expression induces hyperproliferation and aberrant signaling in primary hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood. 2007;109(9):3945–3952. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang J, Liu Y, Beard C, et al. Expression of oncogenic K-ras from its endogenous promoter leads to a partial block of erythroid differentiation and hyperactivation of cytokine-dependent signaling pathways. Blood. 2007;109(12):5238–5241. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang J, Liu Y, Li Z, et al. Endogenous oncogenic NRAS mutation promotes aberrant GM-CSF signaling in granulocytic/monocytic precursors in a murine model of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;116(26):5991–6002. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kotecha N, Flores NJ, Irish JM, et al. Single-cell profiling identifies aberrant STAT5 activation in myeloid malignancies with specific clinical and biologic correlates. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(4):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harir N, Pecquet C, Kerenyi M, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat5 promotes its cytoplasmic localization and association with PI3-kinase in myeloid leukemias. Blood. 2007;109(4):1678–1686. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-029918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Matsuda K, Shimada A, Yoshida N, et al. Spontaneous improvement of hematologic abnormalities in patients having juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia with specific RAS mutations. Blood. 2007;109(12):5477–5480. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fukuda M, Horibe K, Miyajima Y, Matsumoto K, Nagashima M. Spontaneous remission of juvenile chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in an infant with Noonan syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 1997;19(2):177–179. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199703000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Castleberry RP, Emanuel PD, Zuckerman KS, et al. A pilot study of isotretinoin in the treatment of juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331(25):1680–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412223312503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cohen SJ, Ho L, Ranganathan S, et al. Phase II and pharmacodynamic study of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor R115777 as initial therapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(7):1301–1306. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]