Abstract

Aspergillus fumigatus is a saprophytic fungus that causes a range of diseases in humans including invasive aspergillosis. All forms of disease begin with the inhalation of conidia, which germinate and develop. Four stages of early development were evaluated using the gel free system of isobaric tagging for relative and absolute quantitation to determine the full proteomic profile of the pathogen. A total of 461 proteins were identified at 0, 4, 8, and 16 h and fold changes for each were established. Ten proteins including the hydrophobin rodlet protein RodA and a protein involved in melanin synthesis Abr2 were found to decrease relative to conidia. To generate a more comprehensive view of early development, a whole genome microarray analysis was performed comparing conidia to 8 and 16 h of growth. A total of 1871 genes were found to change significantly at 8 h with 1001 genes up-regulated and 870 down-regulated. At 16 h, 1235 genes changed significantly with 855 up-regulated and 380 down-regulated. When a comparison between the proteomics and microarray data was performed at 8 h, a total of 22 proteins with significant changes also had corresponding genes that changed significantly. When the same comparison was performed at 16 h, 12 protein and gene combinations were found. This study, the most comprehensive to date, provides insights into early pathways activated during growth and development of A. fumigatus. It reveals a pathogen that is gearing up for rapid growth by building translation machinery, generating ATP, and is very much committed to aerobic metabolism.

Aspergillus fumigatus is a saprophytic mold that thrives in the soil on organic debris. It sporulates readily with conidiophores producing multitudes of conidia (1). This microbe can also cause disease in humans ranging from invasive aspergillosis in hosts with a compromised immune system to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in hosts with an overactive immune response (2, 3). All manifestations of disease begin with the inhalation of conidia or hyphal elements. In patients with an intact immune system, the conidia are usually cleared by macrophages and neutrophils in both the nose and lungs along with mucocilliary mechanisms (2, 4). When the immune system is compromised by neutropenia, solid organ transplant, advanced AIDS, or several other diseases, the conidia can germinate and invade the lung or surrounding tissue (5). Conidial germination is a process that can be divided into four stages: (1) breaking of spore dormancy; (2) isotropic swelling; (3) establishment of cell polarity; and (4) formation of a germ tube and maintenance of polar growth (6–8). Identifying proteins involved in this process can lead to potential biomarkers of active A. fumigatus infection and could also be used to design and evaluate potential new therapeutic targets in vitro, or examine the efficacy of current treatments in experimental models. Early initiation of antifungal therapy is critical and leads to improved clinical outcomes (1). Conidia have been the focus of much of the research in development thus far because of the fact that they are the first structure that the immune system encounters during an infection (9). Conidia have at least two characteristics that allow them to evade the host immune system: melanin and the outer rodlet layer. The main pigment of A. fumigatus, melanin, is produced by a complex of six genes and has also been shown to have a role in conidia cell wall integrity (10, 11). Colorless mutants of A. fumigatus have also been shown to be less virulent and more easily detectable by the immune system (12). The outer rodlet layer, encoded by rodA and to a lesser extent rodB, functions in masking the conidia from the immune system as well as in cell wall integrity (13–15). Mutations have been generated in A. fumigatus rodA, which yields no rodlet layer, and the spores are readily detected by the immune system (13).

The first positive identification of proteins from conidia yielded 26 proteins (9). Sixteen allergens were also identified from two-dimensional gels using tandem mass spectroscopy which were then tested against patient sera (16). More recently genomic approaches such as real time reverse transcription PCR and macroarray analyses were used to track specific genes during infection. Real time RT-PCR was used to evaluate 12 genes of A. fumigatus from infected mouse lung samples (17), whereas a more comprehensive macroarray study of more than 3000 genes was conducted by Lamarre et al. (8). A recent study used two-dimensional gel electrophoresis to map 449 different proteins present in conidia and two-dimensional differential in-gel electrophoresis to compare the proteins present in resting conidia to those present in mycelia (18). Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis has been the standard approach for the past 20 years, but it has the limitations of profiling only the most highly abundant proteins and difficulty quantifying them (19). The gel free system of isobaric tagging for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ)1 has the ability to simultaneously analyze eight samples while identifying hundreds of proteins with quantitation for each one relative to any other sample (20, 21). To assess the proteins that are both turned on and turned off during the germination process, the iTRAQ system was used to analyze samples kinetically from conidia to young hyphae. In a complementary approach, a whole genome microarray was used to assess the gene expression profile of germinating and developing conidia. These data were validated against previous research in our lab (22) comparing these proteins to those that are increasing and decreasing in response to the echinocandin antifungal drug caspofungin. This is the most comprehensive study to date, simultaneously tracking 461 proteins with quantification over 4 time points as well as using the whole genome microarray to give gene information at two different time points for over 9000 open reading frames. This data is critical for the identification and evaluation of new biomarkers of active A. fumigatus infection and possible new antifungal targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and Culture Conditions

A. fumigatus strain R21 (H11–20)(23), a clinical isolate, was grown at 37 °C on potato dextrose agar (PDA, Becton Dickenson, Sparks, MD) for at least 72 h to generate conidia. Spores were harvested using sterile dH2O containing 0.1% Tween (Sigma Aldrich) and counted using a hemocytometer. Cultures were inoculated at a concentration of 1 × 105 conidia/ml in YPD broth (2% yeast extract, 4% Bacto peptone, 4% dextrose) for 4, 8, and 16 h with shaking at 225 rpm. At 4 h and 8 h, the cultures were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min and the pellet of cellular material was collected. The T16 material was recovered by filtration through Miracloth (CalBiochem, La Jolla, CA) after the allotted time. All material was washed twice with cold sterile dH2O before storage at −80 °C. All material was generated in biological duplicate unless otherwise indicated.

Microarray Analysis

Isolation of RNA from A. fumigatus

Strains were grown for 8 or 16 h in triplicate, as above, and all samples were lysed by crushing in a mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen for a minimum of 5 min. A total of 2.1 × 1011 conidia were used to generate a sufficient amount of RNA to use for microarray analysis. The finely ground powder was then processed using the RNeasy Maxi Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). The ground mycelia was used as the initial sample and resuspended in the kit supplied Buffer RLT. The rest of the protocol was as per the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was DNase treated at 1U/5 ng RNA at 37 °C for 15 min using Turbo DNase (Ambion, Austin, TX) followed by heat inactivation of the enzyme at 75 °C for 5 min. Following DNase treatment the RNA was measured for quantity and purity using RNA Nano Chips and the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany).

Labeling, Prehybridization, and Hybridization of DNA Slides

A. fumigatus total RNA (2 μg) was labeled using protocols outlined by The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) SOP #M007 (http://pfgrc.jcvi.org/index.php/microarray/protocols.html). All slides were whole genome A. fumigatus DNA version 3 (J. Craig Venter Institute, Rockville, MD). SuperScript III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used instead of PowerScript RT in the labeling reactions as PowerScript RT has been discontinued. The hybridization of the labeled probes was performed as per SOP #M008. The coverslips used were thick LifterSlip coverslips (Erie Scientific Company, Portsmouth, NH) and hybridization chamber with an increased depth (Corning, Lowell, MA).

Image Acquisition and Data Analysis

All slides were scanned using an Axon Instruments model 4000B (Molecular Devices, Sunnydale, CA) with each channel being scanned individually. All scans used a 10 μm resolution and were converted into a resolution of 16 bits/pixel. All scanned images were then analyzed using the GenePix Pro 6.1 software. After global normalization in GenePix Pro, SAM analysis was performed on all data using TM4 software (24). The remaining data was then filtered by taking the mean of all data points for that spot (three replicates with dye swap) and any gene with an expression value ≥2 was considered significant.

Biological Theme Determinations

Identification of biological themes that were over-represented was determined using the Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer (EASE) program embedded within the TIGR TM4 software package (25) (http://www.tm4.org). The number of genes in each Gene Ontology category for Biological Process, Cellular component and Molecular Function were compared with the whole genome data set for overrepresented categories and only categories with Fisher's exact test p values <0.05 were included based on previous research (26).

Protein Extraction and iTRAQ Labeling

Conidia (109), 4- and 8-h cells were lysed by crushing for 5 min in a mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen. This material was then resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 20% Glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 mm dithiothreitol) for further processing. The 16 h material was resuspended in lysis buffer and lysed by passing through a French Press at 20,000 psi 5 times. All samples were then spun at 5000 × g to remove cells that were not lysed. The remaining supernatant was then used for downstream protein processing. After acetone precipitation, protein pellets were solubilized in digestion buffer (500 mm TEAB, 1.0% Igepal CA630, 1.0% Triton X-100, Sigma protease inhibitor mixture) and disrupted by sonication in a 4 °C water bath. The sample was adjusted to pH 8.0 with 1.0 m TEAB. One hundred μg of protein from each sample was used for this analysis. After reduction with TCEP and alkylation with MMTS, tryptic digestion was performed by addition of 5 μg of trypsin (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) to each of the eight samples at 37 °C for 14 h. An aliquot of the sample was run on an SDS-PAGE gel and stained with SYPRO ruby to test for complete tryptic digestion. Peptides derived from conidia were labeled with iTRAQ tags 113 and 114, with the 4 h samples being labeled with 115 and 116, 8 h samples labeled with 117 and 118, and the 16 h samples labeled with 119 and 121 as per manufacturer's instructions. The labeled samples were then mixed together and fractionated via two dimensional liquid chromatography as previously described (27). The high-performance liquid chromatography eluent was mixed with matrix solution (7 mg/ml alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 50% acetonitrile, 5 mm of ammonium monobasic phosphate) and the internal mass calibrants, (50 fmol/μl each of [Glu1]-Fibrinopeptide B and adrenocorticotropic hormone fragment 18–39) through a 30 nl mixing tee before directly spotting onto 1650 well matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization plates.

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight/TOF Tandem MS Analysis

The peptides were analyzed on an ABI 4800 Plus matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-TOF/TOF Analyzer with 4000 series explorer software (version 3.5.3) in a data-dependent fashion using a job-wide interpretation method. MS spectra (m/z 800–3600) were acquired in positive ion reflection mode with internal mass calibration. A total of 1000 laser shots were accumulated for each spot. A maximum of fifteen most intense ions (signal-to-noise (S/N) ≥50) per spot were selected for succeeding MS/MS analysis in 2.0 keV mode using air as a collision-induced dissociation gas at pressure of 1 × 10−6 Torr. A total of 4000 laser shots were accumulated for each spectrum.

Protein Database Search and Bioinformatics

TS2Mascot Version 0.0.90 (Matrix Science Inc., Boston, MA) was used to generate a peak list as mascot generic file from tandem MS using parameters: mass range form 20–60 Dalton below precursor, S/N ratio 10. Mascot generic file was submitted for automated search using local Mascot server (version 2.3) against Reverse Concatenated FASTA Database of A. fumigatus protein database (9630 entries, curated from Unirprot Release 2010_12 (downloaded from ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/uniprot/knowledgebase) on November 30, 2010). The following parameters were used; iTRAQ 8plex (K), iTRAQ 8plex (N-terminal) and methylthio (C) as fixed modifications; iTRAQ 8plex (Y) and Oxidation (M) as variable modifications; trypsin as enzyme with maximum one missed cleavage allowed; monoisotopic, peptide tolerance 50 ppm; MS/MS tolerance 0.3 Da. Scaffold (version Scaffold_2_06_01, Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR) was used to validate MS/MS based peptide and protein identifications. Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95.0% probability as specified by the Peptide Prophet algorithm (28). Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 99.0% probability and contained at least two identified peptides. False discovery rate was calculated and was 5.3% at the peptide level and 0.0% at the protein level (29). Protein probabilities were assigned by the Protein Prophet algorithm (30). Proteins that contained similar peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS analysis alone were grouped to satisfy the principles of parsimony. Peptides were quantitated using the centroided reporter ion peak intensity. Intrasample channels were normalized based on the median ratio for each channel across all proteins. Multiple isobaric tag samples were normalized by comparing the median protein ratios for the reference channel. Protein quantitative values were derived from only uniquely assigned peptides. The minimum quantitative value for each spectrum was calculated as 5.0% percent of the highest peak. Protein quantitative ratios were calculated as the median of all peptide ratios. Standard deviations were calculated as the interquartile range around the median. Quantitative ratios were Log2 normalized for final quantitative testing. For each identified protein, associated gene ontology terms were automatically fetched from NCBI by Scaffold software and plotted with respect to enrichment.

RESULTS

Proteomic Signature During Germination and Growth

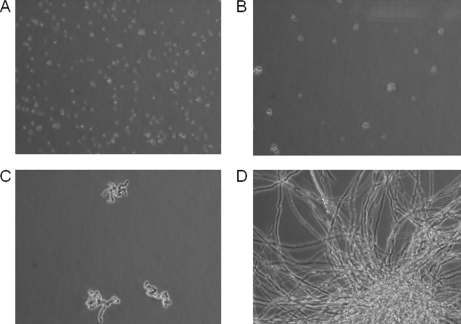

Upon addition of conidia to rich media, they begin uptake of water, swell at 4 h, and establish a germ tube at 8 h; full hyphal branching is evident at 16 h (Fig. 1). To establish the proteomic changes at these critical stages, the system of gel-free iTRAQ was used. The iTRAQ system was able to identify a total of 461 proteins with 231 of these being identified with high confidence (two different peptides derived from a given protein with a confidence of 95% and protein identification of at least 99%). Only high confidence proteins were used for downstream analysis.

Fig. 1.

Aspergillus fumigatus early growth morphology. Microscopic images (40×) of Aspergillus fumigatus strain R21 taken at (A) 0 h, (B) 4 h in which the conidia are beginning to aggregate and swell, (C) 8 h at which germ tubes are beginning to form, and (D) 16 h when full mature mycelia are visible.

A total of 10 proteins were shown to decrease at least twofold at 4, 8, and 16 h. These proteins include abr2, the hydrophobin rodA, heat shock protein hsp30/hsp42, the copper-zinc superoxide dismutase sodC, as well as a putative carboxylase and a putative protein (Table I). The abr2 protein decreased by 10.2-fold at 4 h, 25.2-fold at 8 h and 24.3-fold at 16 h compared with T0. A total of 12 proteins decreased at least twofold in two of the three time points tested. These include a putative decarboxylase which decreased 2.5-fold at 4 h and 6.8-fold at 8 h, transaldolase that decreased 2.6-fold at T4 and 2.7 fold at T8, adenosine kinase that decreased 2.3-fold at T8 and 2.0-fold at T16, GatA that decreased 2.7-fold at T8 and 3.8-fold at T16 along with 1 putative uncharacterized protein (Table I). Another subset of 24 proteins decreased twofold or greater at only a single time point. These include the nucleolin protein Nsr1, which was not significantly changed at 4 or 8 h compared with conidia, but showed at threefold decrease at T16. The same pattern was seen for eEF-3 with a decrease of 2.2-fold, ABC transporter Arb1 with a 2.2-fold decrease, and the RNA helicase ded1. Other proteins showed a significant decrease at T8 including glucose 6 phosphate isomerase at 2.3-fold decreasing, catalase-peroxidase katG decreasing 2.9-fold, protein disulfide isomerase pdi1 at threefold decreasing, and the actin cytoskeleton protein Vip1 decreasing fourfold at T8. There was also a putative uncharacterized protein (AFUA_6G10450) that showed a decrease of 3.7-fold at the T8 time point (Table I). No proteins in the current study showed a decrease at only the 4 h time point.

Table I. All proteins identified by iTRAQ and protein fold changes. Proteins in italics change twofold or greater at all three time points.

| UniProt ID | Molecular Weight | ORF Name | Gene Name | Common Name of Target | 4 HOURS | 8 HOURS | 16 HOURS | Unique Peptides | % Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q4WKG5 | 50 kDa | AFUA_8G00630 | Putative uncharacterized protein | −24.8 | −15.8 | −17.2 | 2 | 6% | |

| Q4WJZ0 | 23 kDa | AFUA_5G09240 | sodC | Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | −18.8 | −19.4 | −6.2 | 4 | 23% |

| Q4WK69 | 32 kDa | AFUA_5G09580 | rodA | Hydrophobin | −10.6 | −18.4 | −10.9 | 3 | 11% |

| Q4WKL3 | 35 kDa | AFUA_2G17530 | abr2 | Brown 2 | −10.2 | −25.2 | −24.3 | 3 | 12% |

| Q4WK23 | 119 kDa | AFUA_3G14540 | Heat shock protein Hsp30/Hsp42, putative | −9.5 | −28.6 | −10.6 | 2 | 2% | |

| Q4WK03 | 81 kDa | AFUA_4G08240 | Zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenase, putative | −4.2 | −12.4 | −6.2 | 7 | 11% | |

| Q4WJR3 | 33 kDa | AFUA_4G13120 | Glutamine synthetase | −3.2 | −3.5 | −2.9 | 3 | 8% | |

| Q4WK14 | 21 kDa | AFUA_4G07710 | Pyruvate carboxylase, putative | −2.8 | −6.8 | −7.0 | 4 | 27% | |

| Q4WP12 | 23 kDa | AFUA_5G09230 | Transaldolase | −2.6 | −2.7 | −1.4 | 2 | 12% | |

| Q4X1C0 | 16 kDa | AFUA_1G11480 | Putative uncharacterized protein | −2.5 | −2.1 | −1.3 | 3 | 17% | |

| Q4WLK1 | 14 kDa | AFUA_3G11070 | pdcA | Pyruvate decarboxylase | −2.5 | −6.8 | 1.7 | 5 | 28% |

| Q4WIE8 | 55 kDa | AFUA_6G06750 | 14-3-3 family protein | −2.3 | −2.8 | −1.5 | 7 | 17% | |

| Q4WJN2 | 33 kDa | AFUA_3G14490 | Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | −2.0 | −2.3 | −2.5 | 2 | 8% | |

| Q4WJW9 | 17 kDa | AFUA_5G02910 | NAP family protein | −2.0 | −2.8 | −4.2 | 2 | 10% | |

| Q4WJQ1 | 120 kDa | AFUA_6G01940 | Dienelactone hydrolase family protein | −2.0 | −5.2 | −2.8 | 3 | 4% | |

| Q4WJN7 | 25 kDa | AFUA_6G06770 | enoA | Enolase | −1.9 | −3.1 | −2.6 | 4 | 15% |

| Q4WJH1 | 23 kDa | AFUA_5G13450 | Triosephosphate isomerase | −1.8 | −2.9 | −2.3 | 5 | 19% | |

| Q4X0L0 | 26 kDa | AFUA_3G08380 | Inorganic diphosphatase, putative | −1.8 | −1.8 | −1.2 | 3 | 14% | |

| Q6MYW4 | 24 kDa | AFUA_3G11690 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, class II | −1.8 | −2.0 | −1.7 | 6 | 29% | |

| Q4WAI8 | 28 kDa | AFUA_4G03410 | Flavohemoprotein | −1.8 | −3.3 | 1.7 | 6 | 23% | |

| Q4WYW9 | 20 kDa | AFUA_7G05740 | Malate dehydrogenase | −1.8 | −0.7 | 0.0 | 5 | 23% | |

| Q4WY39 | 40 kDa | AFUA_3G07430 | asp f 27 | Cyclophilin | −1.8 | −1.9 | −0.5 | 5 | 17% |

| Q6MY48 | 22 kDa | AFUA_1G11190 | Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 subunit Eef1-beta, putative | −1.8 | −1.4 | −1.5 | 5 | 24% | |

| Q4WTV5 | 37 kDa | AFUA_6G04920 | NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase AciA/Fdh | −1.8 | −3.1 | 1.2 | 3 | 11% | |

| Q4WCP3 | 35 kDa | AFUA_1G04620 | Alcohol dehydrogenase, zinc-containing, putative | −1.7 | −2.2 | 1.3 | 2 | 6% | |

| Q4WC88 | 60 kDa | AFUA_3G06460 | Putative uncharacterized protein | −1.7 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 9 | 19% | |

| P61832 | 15 kDa | AFUA_7G00250 | Tubulin beta chain | −1.7 | −2.1 | −1.6 | 3 | 16% | |

| Q4WIE3 | 13 kDa | AFUA_8G01670 | katG | Catalase-peroxidase | −1.7 | −2.9 | −1.4 | 2 | 14% |

| Q4X1I3 | 32 kDa | AFUA_5G10780 | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | −1.6 | −3.0 | −1.3 | 3 | 10% | |

| Q4WGP3 | 36 kDa | AFUA_5G14680 | Putative uncharacterized protein | −1.6 | −2.9 | 2.1 | 6 | 29% | |

| Q4WLN1 | 86 kDa | AFUA_2G03720 | cpr2 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase B | −1.6 | −0.8 | 1.6 | 8 | 12% |

| Q4WDF5 | 54 kDa | AFUA_5G06240 | Alcohol dehydrogenase, putative | −1.6 | −1.8 | 1.3 | 8 | 18% | |

| Q4WLM5 | 29 kDa | AFUA_1G10350 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | −1.6 | −1.4 | 1.7 | 10 | 39% | |

| Q4WT91 | 48 kDa | AFUA_1G05080 | 60S ribosomal protein P0 | −1.6 | −1.4 | −1.9 | 6 | 17% | |

| Q4WJR7 | 45 kDa | AFUA_2G10070 | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, large subunit | −1.6 | −2.3 | −2.9 | 3 | 12% | |

| Q4WCM2 | 67 kDa | AFUA_8G05600 | Putative uncharacterized protein | −1.6 | −1.9 | 2.5 | 4 | 7% | |

| Q4WNZ0 | 19 kDa | AFUA_6G02280 | pmp20 | Putative peroxiredoxin pmp20 | −1.6 | −2.2 | 0.4 | 3 | 14% |

| Q4WP16 | 65 kDa | AFUA_6G04740 | Actin Act1 | −1.6 | −1.5 | 1.1 | 2 | 5% | |

| Q4WJV9 | 38 kDa | AFUA_5G06680 | 4-aminobutyrate transaminase GatA | −1.5 | −2.7 | −3.8 | 2 | 8% | |

| Q4WWF0 | 17 kDa | AFUA_3G04220 | Fatty acid synthase beta subunit, putative | −1.5 | −1.8 | −1.2 | 3 | 18% | |

| Q4WZS4 | 48 kDa | AFUA_2G16090 | Karyopherin alpha subunit, putative | −1.5 | −1.1 | −1.2 | 2 | 11% | |

| Q4WEU5 | 52 kDa | AFUA_5G02450 | Farnesyl-pyrophosphate synthetase | −1.4 | −1.2 | 1.2 | 6 | 16% | |

| Q4WXW4 | 37 kDa | AFUA_4G11550 | Putative uncharacterized protein | −1.4 | 0.1 | −0.7 | 11 | 32% | |

| Q4WEB8 | 40 kDa | AFUA_5G08830 | Woronin body protein HexA, putative | −1.4 | −1.8 | 1.2 | 3 | 8% | |

| Q4WQK8 | 35 kDa | AFUA_1G14200 | Mitochondrial processing peptidase beta subunit, putative | −1.4 | −1.3 | 1.1 | 8 | 21% | |

| Q6MYM6 | 45 kDa | AFUA_8G03930 | Hsp70 chaperone (HscA), putative | −1.4 | −1.5 | −1.7 | 2 | 9% | |

| P41746 | 16 kDa | AFUA_7G05720 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase component, putative | −1.4 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 2 | 19% | |

| Q4WTJ3 | 22 kDa | AFUA_5G06390 | Adenosine kinase, putative | −1.4 | −2.3 | −2.0 | 6 | 30% | |

| Q4WYD9 | 60 kDa | AFUA_2G03720 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | −1.4 | −1.7 | −0.4 | 3 | 4% | |

| Q4WMB9 | 27 kDa | AFUA_2G11060 | Acyl CoA binding protein family | −1.4 | −2.1 | 1.5 | 3 | 17% | |

| Q4WJD7 | 21 kDa | AFUA_6G11620 | Formyltetrahydrofolate deformylase, putative | −1.4 | −2.2 | −2.3 | 5 | 30% | |

| Q4WJ94 | 13 kDa | AFUA_6G08050 | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating | −1.3 | −2.5 | −2.2 | 2 | 8% | |

| Q4X205 | 12 kDa | AFUA_2G06150 | Protein disulfide isomerase Pdi1, putative | −1.3 | −3.0 | −1.3 | 4 | 21% | |

| Q4WZM7 | 53 kDa | AFUA_2G10030 | Actin cytoskeleton protein (VIP1), putative | −1.3 | −4.0 | −1.2 | 2 | 5% | |

| Q4WLQ2 | 9 kDa | AFUA_2G03010 | Cytochrome c subunit Vb, putative | −1.3 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 3 | 23% | |

| Q4WT53 | 23 kDa | AFUA_2G09790 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | −1.3 | −2.3 | −1.9 | 5 | 12% | |

| Q873W8 | 16 kDa | AFUA_1G09440 | rps23 | 40S ribosomal protein S23 | −1.3 | −1.7 | −2.0 | 4 | 23% |

| Q4WHU8 | 20 kDa | AFUA_6G05210 | Malate dehydrogenase, NAD-dependent | −1.3 | −2.3 | −1.4 | 6 | 36% | |

| Q4WWC7 | 48 kDa | AFUA_1G13490 | Spermidine synthase | −1.3 | −1.2 | −1.2 | 4 | 15% | |

| Q4WP13 | 72 kDa | AFUA_2G13010 | Cytochrome c oxidase polypeptide vib | −1.3 | −1.7 | 1.1 | 4 | 6% | |

| Q4WWX5 | 18 kDa | AFUA_1G03510 | ATP synthase gamma chain | −1.3 | −1.7 | −1.1 | 6 | 39% | |

| Q4WV25 | 56 kDa | AFUA_4G07580 | Translation initiation factor EF-2 gamma subunit, putative | −1.2 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 13 | 32% | |

| Q4WE70 | 36 kDa | AFUA_6G03810 | ATP synthase D chain, mitochondrial, putative | −1.2 | −1.1 | 1.1 | 5 | 14% | |

| Q4WI29 | 29 kDa | AFUA_1G10630 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase | −1.2 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 3 | 13% | |

| Q4WSG1 | 35 kDa | AFUA_5G07120 | RNP domain protein | −1.2 | −1.4 | −1.7 | 8 | 36% | |

| Q4WYL7 | 35 kDa | AFUA_8G05320 | ATP synthase subunit alpha | −1.2 | −1.2 | −0.4 | 2 | 3% | |

| Q4WSY6 | 25 kDa | AFUA_1G13500 | Transketolase TktA | −1.2 | −2.0 | −1.7 | 8 | 45% | |

| Q4WRN1 | 15 kDa | AFUA_4G07360 | Cobalamin-independent methionine synthase MetH/D | −1.2 | −2.2 | −1.5 | 2 | 16% | |

| Q4WMV5 | 53 kDa | AFUA_5G01970 | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | −1.1 | −1.2 | 1.5 | 2 | 6% | |

| Q4WP20 | 20 kDa | AFUA_5G10550 | ATP synthase subunit beta | −1.1 | −1.2 | 1.1 | 4 | 16% | |

| Q4WGP1 | 52 kDa | AFUA_4G12450 | 57 kDa immunogenic protein | −1.1 | −1.2 | 2.1 | 3 | 13% | |

| Q6MY77 | 57 kDa | AFUA_4G13700 | Threonyl-tRNA synthetase, putative | −1.1 | −1.4 | −1.5 | 3 | 7% | |

| Q4WX01 | 58 kDa | AFUA_4G13170 | G-protein comlpex beta subunit CpcB | −1.1 | 1.1 | −1.1 | 2 | 4% | |

| Q7Z7W6 | 84 kDa | AFUA_6G07720 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase AcuF | −1.0 | −2.3 | 2.4 | 2 | 3% | |

| Q4WGJ9 | 17 kDa | AFUA_6G03820 | egd2 | Nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha | −0.8 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 3 | 20% |

| Q4WZH8 | 10 kDa | AFUA_1G05390 | Mitochondrial ADP,ATP carrier protein (Ant), putative | −0.8 | 0.6 | −1.2 | 4 | 48% | |

| Q9C177 | 23 kDa | AFUA_6G07770 | Alanine aminotransferase, putative | −0.7 | −1.6 | 1.4 | 2 | 12% | |

| Q4X0D4 (+1) | 16 kDa | AFUA_3G05600 | 60S ribosomal protein L27a, putative | −0.7 | 1.2 | −1.2 | 3 | 23% | |

| Q4WND4 | 30 kDa | AFUA_2G15940 | Cofactor for methionyl-and glutamyl-tRNA synthetases, putative | −0.7 | −1.6 | −1.4 | 4 | 14% | |

| Q4WTP5 | 16 kDa | AFUA_2G02100 | Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase | −0.7 | −0.4 | 1.2 | 4 | 25% | |

| Q4WT69 | 45 kDa | AFUA_6G12930 | Mitochondrial aconitate hydratase, putative | −0.6 | −1.9 | −1.9 | 7 | 21% | |

| Q4WN34 | 55 kDa | AFUA_3G05370 | Dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase, putative | −0.6 | −1.1 | 1.5 | 6 | 13% | |

| Q4WYA0 | 13 kDa | AFUA_5G03490 | ndk1 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | −0.6 | −1.3 | −0.4 | 2 | 18% |

| Q4WWC5 | 15 kDa | AFUA_2G13860 | Histone H4 | −0.6 | 0.6 | −1.2 | 6 | 34% | |

| Q8TGG6 | 48 kDa | AFUA_4G09140 | l-ornithine aminotransferase Car2, putative | −0.6 | −1.7 | −1.7 | 5 | 15% | |

| Q4WJK8 | 29 kDa | AFUA_1G05500 | 40S ribosomal protein S12 | −0.6 | −1.8 | −2.3 | 7 | 29% | |

| Q4X0M1 | 11 kDa | AFUA_1G02070 | Cytochrome C1/Cyt1, putative | −0.6 | −1.3 | −1.2 | 4 | 45% | |

| Q4WSZ2 | 22 kDa | AFUA_2G04310 | Argininosuccinate synthase | −0.5 | −1.6 | −1.8 | 8 | 38% | |

| Q9Y8D9 | 16 kDa | AFUA_6G04570 | Translation elongation factor eEF-1 subunit gamma, putative | −0.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 2 | 21% | |

| Q4WT41 | 42 kDa | AFUA_1G13710 | Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase, cytoplasmic | −0.4 | −1.9 | −1.8 | 6 | 17% | |

| Q6MYM4 | 80 kDa | AFUA_2G16400 | Translation initiation factor 4B | −0.4 | −1.3 | −1.7 | 8 | 12% | |

| Q4WX86 | 31 kDa | AFUA_1G10130 | Adenosylhomocysteinase | −0.4 | −1.2 | −1.1 | 2 | 8% | |

| Q4X1G1 | 18 kDa | AFUA_5G07300 | Electron transfer flavoprotein, beta subunit, putative | −0.4 | −1.6 | −1.3 | 2 | 10% | |

| Q4X1E0 | 24 kDa | AFUA_6G02470 | Fumarate hydratase, putative | −0.2 | −1.9 | −1.3 | 5 | 34% | |

| Q4WI99 | 62 kDa | AFUA_1G06960 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha subunit, putative | −0.2 | −1.5 | −1.4 | 2 | 7% | |

| Q4WHT0 | 46 kDa | AFUA_6G13550 | Ribosomal protein S13p/S18e | −0.1 | −0.6 | −1.4 | 2 | 5% | |

| Q4WEH4 | 41 kDa | AFUA_6G10660 | ATP citrate lyase subunit (Acl), putatibe | −0.1 | −1.4 | 1.2 | 10 | 32% | |

| Q4WNH3 | 50 kDa | AFUA_5G10560 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit V | −0.1 | −1.4 | 1.4 | 7 | 17% | |

| Q4WRU9 | 26 kDa | AFUA_5G04160 | NTF2 and RRM domain protein | −0.1 | −1.5 | −1.5 | 5 | 21% | |

| Q4WAQ6 | 15 kDa | AFUA_3G08770 | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit GRIM-19, putative | −0.1 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 8 | 41% | |

| Q4X1P9 | 11 kDa | AFUA_4G11050 | NADH−ubiquinone oxidoreductase, subunit F, putative | −0.1 | −1.4 | −1.3 | 2 | 11% | |

| Q4WTW7 | 27 kDa | AFUA_6G10650 | ATP citrate lyase, subunit 1, putative | −0.1 | −1.4 | 1.2 | 6 | 28% | |

| Q4WTX0 | 37 kDa | AFUA_1G12170 | Elongation factor Tu | −0.1 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 3 | 11% | |

| Q4WYW4 | 56 kDa | AFUA_5G06130 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase alpha subunit, putative | 0.0 | −0.2 | −0.1 | 2 | 4% | |

| Q4W9L9 | 26 kDa | AFUA_3G07640 | Plasma membrane H+-ATPase Pma1 | 0.0 | −1.6 | 0.0 | 9 | 37% | |

| Q4WP18 | 131 kDa | AFUA_1G07440 | Molecular chaperone Hsp70 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 2 | 3% | |

| Q4WXX9 | 63 kDa | AFUA_3G13320 | rps0 | 40S ribosomal protein S0 | 0.0 | 1.3 | −0.7 | 3 | 7% |

| Q4WRF2 | 10 kDa | AFUA_6G06370 | NAD(+)-isocitrate dehydrogenase subunit I | 0.0 | −1.5 | −1.5 | 5 | 29% | |

| Q8TF79 | 122 kDa | AFUA_8G03880 | Alanyl-tRNA synthetase, putative | 0.0 | −1.8 | −1.6 | 3 | 3% | |

| Q876M7 | 90 kDa | AFUA_6G05200 | 60S ribosomal protein L28 | 0.0 | 1.2 | −1.2 | 3 | 5% | |

| Q4WJ75 | 41 kDa | AFUA_5G07020 | Ribosome biogenesis ABC transporter Arb1, putative | 0.0 | −1.2 | −2.2 | 2 | 5% | |

| Q4WYK1 | 32 kDa | AFUA_4G09870 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 0.0 | −1.6 | −0.4 | 5 | 20% | |

| Q4WQR1 | 84 kDa | AFUA_5G04170 | hsp90 | Heat shock protein 90 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 3 | 5% |

| Q4WUL0 | 61 kDa | AFUA_2G02590 | Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase Dps1, putative | 0.0 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2 | 4% | |

| Q4WA70 (+1) | 50 kDa | AFUA_2G08130 | 60S ribosomal protein L44 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 2 | 6% | |

| Q4WGN6 | 118 kDa | AFUA_2G10090 | 40S ribosomal protein S15, putative | 0.0 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 7 | 8% | |

| Q4WZR7 | 71 kDa | AFUA_3G09320 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | 0.0 | −1.3 | −1.2 | 2 | 5% | |

| Q4WH99 | 56 kDa | AFUA_2G03290 | 14-3-3 family protein ArtA, putative | 0.0 | −1.6 | −1.3 | 3 | 7% | |

| Q4WU60 | 28 kDa | AFUA_1G04070 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF-5A | 0.0 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 2 | 10% | |

| Q4WMU1 | 38 kDa | AFUA_1G11130 | 60S ribosomal protein L6 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2 | 9% | |

| Q4WC61 | 9 kDa | AFUA_2G13110 | Cytochrome c | 0.0 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 3 | 39% | |

| Q4WI57 | 22 kDa | AFUA_4G11650 | Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex subunit Kgd1, putative | 0.0 | −1.5 | −1.4 | 4 | 35% | |

| Q4WTN7 | 48 kDa | AFUA_1G11710 | Ribosomal protein L1 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 2 | 5% | |

| Q4WEE8 | 18 kDa | AFUA_6G02520 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF-1A subunit, putative | 0.0 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 4 | 23% | |

| Q4WUP8 | 35 kDa | AFUA_6G06900 | GTPase Rho1 | 0.1 | −1.3 | 1.2 | 4 | 16% | |

| Q4WQD6 | 57 kDa | AFUA_2G16820 | Curved DNA-binding protein (42 kDa protein) | 0.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 12 | 23% | |

| Q4WHY9 | 22 kDa | AFUA_2G16010 | Prolyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.1 | −1.4 | −1.4 | 2 | 11% | |

| Q4X1J1 | 61 kDa | AFUA_1G12590 | La protein homolog, putative | 0.1 | 1.6 | −1.3 | 2 | 3% | |

| Q4WLH1 | 15 kDa | AFUA_5G02750 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit Va, putative | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 4 | 24% | |

| Q4WW75 | 25 kDa | AFUA_6G10450 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 0.2 | −3.7 | 1.3 | 6 | 33% | |

| Q4WRB8 | 20 kDa | AFUA_2G10500 | 40S ribosomal protein Rps16, putative | 0.3 | −1.3 | −1.5 | 4 | 23% | |

| Q4WN06 | 56 kDa | AFUA_3G11260 | Ubiquitin (UbiC), putative | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 3 | 6% | |

| Q4WPG1 | 49 kDa | AFUA_1G06390 | Elongation factor 1-alpha | 0.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 3 | 9% | |

| Q4WP70 | 37 kDa | AFUA_1G04320 | Ribosomal protein S8 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 2 | 7% | |

| Q4WWR1 | 18 kDa | AFUA_1G12610 | hsp88 | Heat shock protein Hsp88, putative | 0.4 | 1.1 | −1.1 | 3 | 15% |

| Q4WD82 | 16 kDa | AFUA_5G04230 | Citrate synthase | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 3 | 24% | |

| Q4WZI4 | 47 kDa | AFUA_1G04530 | Ribosomal L18ae protein family | 0.4 | 1.3 | −1.2 | 4 | 12% | |

| Q4X220 | 25 kDa | AFUA_3G08600 | Translational initiation factor 2 beta | 0.4 | −1.2 | −1.3 | 4 | 18% | |

| Q4X1P8 | 26 kDa | AFUA_3G12690 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 0.4 | −1.5 | −1.3 | 7 | 30% | |

| Q4WWZ4 | 109 kDa | AFUA_1G09100 | 60S ribosomal protein L9, putative | 0.4 | 1.3 | −1.1 | 3 | 4% | |

| Q6MY67 | 33 kDa | AFUA_1G03970 | Mitochondrial translation initiation factor IF-2, putative | 0.5 | −1.2 | −1.5 | 4 | 10% | |

| Q4WDM0 | 35 kDa | AFUA_3G05350 | htb1 | Histone H2B | 0.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2 | 10% |

| Q4WWT2 | 27 kDa | AFUA_3G06970 | 40S ribosomal protein S9 | 0.6 | 1.2 | −1.1 | 4 | 20% | |

| Q9UVW1 | 65 kDa | AFUA_1G05040 | Protein mitochondrial targeting protein (Mas1), putative | 0.6 | −0.6 | −1.2 | 2 | 4% | |

| Q4WSV7 | 20 kDa | AFUA_2G10010 | Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay protein (Nmd5), putative | 0.6 | −1.2 | −1.7 | 2 | 9% | |

| Q4WM42 | 30 kDa | AFUA_2G07380 | Ribosomal protein L18 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 4 | 10% | |

| Q4WZQ9 | 61 kDa | AFUA_6G03830 | Ribosomal protein L14 | 0.8 | −1.2 | −1.2 | 3 | 6% | |

| Q4WEX7 | 205 kDa | AFUA_1G02550 | Tubulin alpha-1 subunit | 0.8 | −1.5 | −1.2 | 6 | 3% | |

| Q4WJV5 | 28 kDa | AFUA_3G07710 | Nucleolin protein Nsr1, putative | 1.0 | 0.8 | −3.0 | 4 | 19% | |

| Q4WEV9 | 73 kDa | AFUA_5G03020 | 60S ribosomal protein L4, putative | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 2 | 4% | |

| Q4WXF4 | 52 kDa | AFUA_3G06840 | 40S ribosomal protein S4, putative | 1.1 | 1.3 | −1.1 | 6 | 15% | |

| Q4WP49 | 70 kDa | AFUA_1G04190 | pab1 | Polyadenylate-binding protein, cytoplasmic and nuclear | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 2 | 5% |

| Q4WD81 | 22 kDa | AFUA_2G07970 | 60S ribosomal protein L19 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 3 | 21% | |

| Q8NKF4 | 44 kDa | AFUA_2G04130 | 40S ribosomal protein S11 | 1.1 | −0.4 | −1.3 | 14 | 35% | |

| Q4X1G7 | 28 kDa | AFUA_5G06360 | 60S ribosomal protein L8, putative | 1.1 | −1.1 | −1.3 | 2 | 8% | |

| Q4WWT1 | 18 kDa | AFUA_2G16370 | 60S ribosomal protein L32 | 1.1 | 1.2 | −1.1 | 4 | 28% | |

| Q4WJD2 | 54 kDa | AFUA_7G05660 | Translation elongation factor eEF-3, putative | 1.1 | 0.4 | −2.2 | 16 | 41% | |

| Q4WJ30 | 70 kDa | AFUA_4G07660 | ded1 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase ded1 | 1.1 | −1.7 | −2.1 | 19 | 30% |

| Q4X1G9 | 119 kDa | AFUA_1G05200 | tif32 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit A | 1.2 | 1.2 | −1.3 | 2 | 2% |

| Q4WWN1 | 16 kDa | AFUA_3G08160 | tif1 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase eIF4A | 1.2 | 1.1 | −1.2 | 3 | 31% |

| Q4WP05 | 56 kDa | AFUA_2G10300 | 40S ribosomal protein S17, putative | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 2 | 5% | |

| Q4WV26 | 22 kDa | AFUA_1G13790 | hhtA | Histone H3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 4 | 23% |

| Q4WI54 | 21 kDa | AFUA_6G07430 | Pyruvate kinase | 1.2 | −1.2 | −1.4 | 3 | 14% | |

| Q4WU42 | 37 kDa | AFUA_1G16523 | 40S ribosomal protein S25, putative | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 4 | 16% | |

| Q4WX09 | 71 kDa | AFUA_5G05630 | 60S ribosomal protein L23 | 1.2 | 1.2 | −1.1 | 4 | 8% | |

| Q4X0G7 | 93 kDa | AFUA_1G10510 | 60S ribosomal protein L35 | 1.2 | 1.2 | −1.2 | 17 | 23% | |

| Q4X279 | 21 kDa | AFUA_2G09870 | tif35 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit G | 1.2 | −1.1 | −1.3 | 2 | 11% |

| Q4WB08 | 37 kDa | AFUA_7G04210 | Tropomyosin, putative | 1.2 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 2 | 6% | |

| Q4WCV0 | 21 kDa | AFUA_4G06910 | Outer mitochondrial membrane protein porin | 1.2 | −1.5 | 1.3 | 2 | 15% | |

| Q4WXA2 | 15 kDa | AFUA_2G09960 | Mitochondrial Hsp70 chaperone (Ssc70), putative | 1.2 | 1.1 | −1.1 | 2 | 21% | |

| Q6MYD1 | 33 kDa | AFUA_3G01110 | gua1 | GMP synthase [glutamine-hydrolyzing] | 1.2 | −1.1 | −1.6 | 3 | 10% |

| Q4WCX4 | 21 kDa | AFUA_1G12890 | 60S ribosomal protein L5, putative | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 4 | 20% | |

| Q4WZN0 | 15 kDa | AFUA_7G02140 | 40S ribosomal protein S24 | 1.2 | 1.2 | −1.2 | 4 | 30% | |

| Q4WM07 | 32 kDa | AFUA_6G12720 | 40S ribosomal protein S29, putative | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 3 | 13% | |

| Q4WD80 | 29 kDa | AFUA_1G16840 | Translationally-controlled tumor protein homolog | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 6 | 31% | |

| Q4WCU6 | 63 kDa | AFUA_3G12300 | 60S ribosomal protein L22, putative | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 4 | 7% | |

| Q4WFT3 | 61 kDa | AFUA_1G05630 | 40S ribosomal protein S3, putative | 1.3 | 1.2 | −1.2 | 4 | 7% | |

| Q4WQK3 | 40 kDa | AFUA_4G03860 | nip1 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit C | 1.3 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 3 | 8% |

| Q4WVI1 | 28 kDa | AFUA_3G10920 | Telomere and ribosome associated protein Stm1, putative | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 3 | 15% | |

| Q4WXZ8 | 18 kDa | AFUA_1G15020 | 40S ribosomal protein S5, putative | 1.3 | 1.3 | −0.6 | 6 | 36% | |

| Q4W9S8 | 98 kDa | AFUA_2G09210 | 60S ribosomal protein L10 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 2 | 4% | |

| Q4WWR9 | 29 kDa | AFUA_1G06340 | 60S ribosomal protein L27 | 1.3 | 1.3 | −1.1 | 9 | 33% | |

| Q4WX65 | 44 kDa | AFUA_2G13530 | Translation elongation factor EF-2 subunit, putative | 1.3 | 1.2 | −1.1 | 7 | 18% | |

| Q4WX73 | 13 kDa | AFUA_1G06770 | 40S ribosomal protein S26 | 1.3 | 1.1 | −1.1 | 2 | 6% | |

| Q4WVV5 | 28 kDa | AFUA_2G03040 | Ribosomal protein L34 protein, putative | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 3 | 14% | |

| Q4X1M0 | 164 kDa | AFUA_2G11850 | rpl3 | 60S ribosomal protein L3 | 1.3 | −1.1 | −1.3 | 3 | 2% |

| Q4W9U9 | 51 kDa | AFUA_1G15730 | 40S ribosomal protein S22 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 2 | 6% | |

| P40292 | 81 kDa | AFUA_3G04210 | Fatty acid synthase alpha subunit FasA | 1.3 | −1.2 | 1.2 | 15 | 19% | |

| Q4W9S6 | 34 kDa | AFUA_5G05540 | Nucleosome assembly protein Nap1, putative | 1.3 | −1.1 | 0.0 | 7 | 24% | |

| Q4WDJ0 | 46 kDa | AFUA_4G07730 | 60S ribosomal protein L11 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 7 | 19% | |

| Q7Z8P9 | 17 kDa | AFUA_6G13250 | 60S ribosomal protein L31e | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 4 | 36% | |

| Q4WX43 | 46 kDa | AFUA_7G01460 | Ribosomal protein S5 | 1.3 | 1.2 | −1.1 | 7 | 19% | |

| Q4WN39 | 67 kDa | AFUA_6G12660 | 40S ribosomal protein S10b | 1.4 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2 | 5% | |

| Q4WDH2 | 44 kDa | AFUA_3G06960 | 60S ribosomal protein L21, putative | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 5 | 16% | |

| Q4WNT7 | 37 kDa | AFUA_4G08030 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 5 | 16% | |

| Q4X1G3 | 129 kDa | AFUA_2G17110 | 25d9-4 | Cdc48p | 1.4 | −1.4 | −1.3 | 3 | 4% |

| Q4WSA0 | 75 kDa | AFUA_4G03650 | Ribosome associated DnaJ chaperone Zuotin, putative | 1.4 | −1.2 | −1.6 | 9 | 13% | |

| Q4WEX6 | 232 kDa | AFUA_2G09490 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor subunit eIF-4F, putative | 1.4 | 1.1 | −1.2 | 6 | 4% | |

| Q4WNT6 | 72 kDa | AFUA_1G14410 | rpl17 | 60S ribosomal protein L17 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 2 | 2% |

| Q4WQ57 | 119 kDa | AFUA_2G09200 | 60S ribosomal protein L30, putative | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 8 | 11% | |

| Q4WEG3 | 41 kDa | AFUA_3G13480 | Translation initiation factor 2 alpha subunit, putative | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 2 | 4% | |

| Q4WET8 | 57 kDa | AFUA_1G04660 | Ribosomal protein L15 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 2 | 4% | |

| Q4WTU5 | 35 kDa | AFUA_3G10730 | 40S ribosomal protein S7e | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 4 | 15% | |

| Q4WDL9 | 17 kDa | AFUA_3G07810 | Succinate dehydrogenase subunit Sdh1, putative | 1.4 | −1.1 | 1.3 | 3 | 15% | |

| Q4WM99 | 79 kDa | AFUA_6G02750 | egd1 | Nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit beta | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 9 | 13% |

| Q4WQ47 | 34 kDa | AFUA_4G03880 | 60S ribosomal protein L7 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2 | 7% | |

| Q4WPX5 | 27 kDa | AFUA_5G04370 | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase, subunit G, putative | 1.5 | −1.1 | 1.1 | 5 | 19% | |

| Q4WCU3 | 18 kDa | AFUA_1G14120 | Nuclear segregation protein (Bfr1), putative | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 3 | 17% | |

| Q4WJ44 | 47 kDa | AFUA_4G06900 | Asparagine synthetase Asn2, putative | 1.5 | −1.4 | −2.1 | 4 | 10% | |

| Q4X1H5 | 74 kDa | AFUA_6G08720 | 5′-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (Meu1), putative | 1.5 | 1.2 | −1.3 | 8 | 13% | |

| Q4WLQ8 | 18 kDa | AFUA_6G02440 | 60S ribosomal protein L24a | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 3 | 10% | |

| Q4WPN3 | 14 kDa | AFUA_4G04460 | 60S ribosomal protein L13 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 2 | 8% | |

| Q4WG92 | 18 kDa | AFUA_3G06760 | Ribosomal protein L37 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2 | 14% | |

| Q4WV46 | 41 kDa | AFUA_2G08670 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2 | 8% | |

| Q4WNY2 | 87 kDa | AFUA_4G07435 | 60S ribosomal protein L36 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 8 | 13% | |

| Q4WTM9 | 29 kDa | AFUA_6G12990 | Cytosolic large ribosomal subunit protein L7A | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 7 | 35% | |

| Q4WS30 | 53 kDa | AFUA_1G14220 | Fibrillarin | 1.6 | 1.2 | −1.5 | 4 | 12% | |

| Q4WM98 | 53 kDa | AFUA_2G16880 | 60S ribosomal protein L37a | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 7 | 18% | |

| Q4X164 | 17 kDa | AFUA_1G07280 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 1.7 | −1.1 | −1.3 | 4 | 29% | |

| Q4WU32 | 70 kDa | AFUA_3G08460 | 60S ribosomal protein L35Ae | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 2 | 6% | |

| Q4WN66 | 58 kDa | AFUA_4G10800 | 40S ribosomal protein S6 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 5 | 9% | |

| O43099 | 18 kDa | AFUA_7G05290 | 40S ribosomal protein S13 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 5 | 27% | |

| Q96X30 | 47 kDa | AFUA_2G02150 | 40S ribosomal protein S10a | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 11 | 32% | |

| Q4WXU5 | 23 kDa | AFUA_6G11260 | Ribosomal protein L26 | 1.8 | 1.2 | −1.1 | 8 | 34% | |

| Q6J9U0 | 77 kDa | AFUA_5G05450 | rps1 | 40S ribosomal protein S1 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 2 | 4% |

| Q4WPZ9 | 55 kDa | AFUA_1G05990 | Ribosomal protein L16a | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 3 | 5% | |

| Q4W9X3 | 46 kDa | AFUA_1G05340 | 40S ribosomal protein S19 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 3 | 10% | |

| Q4WJM1 | 16 kDa | AFUA_6G08580 | fpr4 | FK506-binding protein 4 | 1.9 | 2.1 | −2.4 | 3 | 20% |

| Q4WCM7 | 114 kDa | AFUA_5G12180 | Ran-specific GTPase-activating protein 1, putative | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2 | 2% | |

| Q4X1V2 | 255 kDa | AFUA_6G06340 | Glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase | 2.2 | −1.5 | −1.3 | 2 | 1% | |

| Q4WTZ9 | 55 kDa | AFUA_4G07690 | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazolecarboxamide formyltransferase/IMP cyclohydrolase | 2.3 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 2 | 5% |

A total of 24 proteins showed an increase of twofold or greater over the time course (Table I). However, only one protein showed an increase of greater than twofold at all three time points tested, the RAN-specific GTPase activating protein 1. This protein increased 2.1-fold at 4 h, 2.1-fold at 8 h, and 2.5-fold at 16 h.

Some proteins such as fpr4 showed a biphasic increase of 2.1-fold at T8 and a decrease of 2.4-fold at T16. Other proteins such as the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase AcuF decreased 2.3-fold at T8 with an increase of 2.4-fold at T16. One putative uncharacterized protein (AFUA_5G14680) showed a similar pattern with a decrease of 2.9-fold at T8 and an increase of 2.1-fold at T16 (Table I).

Genomic Changes

Microarray analysis was performed in parallel to test differences in gene expression between cells at T0 versus T8 as well as T0 versus T16. A total of 1871 genes were found to have significant changes in expression (twofold or greater) at 8 h compared with conidia (supplementary Table S1). Of these genes, 1001 were up-regulated and 870 were down-regulated. The gene with the most dramatic decrease was the ComA domain protein with a decrease of 153.7-fold. Three other genes including a monosaccharide transporter, a hypothetical protein (AFUA_6G12000) and an alcohol dehydrogenase all had decreases in fold change greater than 100 (Table II and supplementary Table S1). The largest changes in up-regulation were seen in HEX1 with a fold change of 34.2 and c-4 methyl sterol oxidase with an increase of 29.6-fold (Table II and supplementary Table S1). Gene Ontology information indicated that the favored biological processes for the 870 genes that decreased included fatty acid β-oxidation, fatty acid catabolism, autophagy, and the hyperosmotic response. Their localization is likely to be in the peroxisomal matrix or membrane and the molecular function is involved in zinc ion binding, RNA polymerase II transcription factor activity, or two component sensor activity (supplementary Table S2). Of the 1001 genes that increased the most dominant biological process induced is translation involving both the large and small cytosolic ribosomal subunits (supplementary Table S3).

Table II. Genes with largest changes at 8 and 16 hours and GO terms associated with gene changes.

| ORF Name | Common Name of Target | Average Fold Change |

|---|---|---|

| 8 Hours Microarray Data | ||

| AFUA_8G04550 | ComA domain protein | −153.7 |

| AFUA_5G01160 | monosaccharide transporter | −120.9 |

| AFUA_6G12000 | hypothetical protein | −120.4 |

| AFUA_7G01010 | alcohol dehydrogenase, putative | −103.3 |

| AFUA_8G02440 | c-4 methyl sterol oxidase | 29.6 |

| AFUA_5G08830 | HEX1 | 34.2 |

| 16 Hours Microarray Data | ||

| AFUA_4G13510 | isocitrate lyase | −172.8 |

| AFUA_1G01490 | hypothetical protein | −158.5 |

| AFUA_5G10050 | cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, putative | −150.8 |

| AFUA_5G01160 | monosaccharide transporter | −142.0 |

| AFUA_6G12000 | hypothetical protein | −135.5 |

| AFUA_5G10070 | dehydrogenase | −115.5 |

| AFUA_4G09600 | GPI anchored protein, putative | −114.8 |

| AFUA_7G01010 | alcohol dehydrogenase, putative | −107.8 |

| AFUA_2G03830 | allergen Asp F4 | 89.2 |

| AFUA_2G09030 | secreted dipeptidyl peptidase | 93.4 |

| AFUA_2G11520 | MFS monosaccharide transporter, putative | 98.5 |

| AFUA_4G01290 | endo-chitosanase, pseudogene | 115.3 |

| File | Term | List Hits | List Size | Pop. Hits | Pop. Size | Fisher's Exact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 Hour | |||||||

| GO Biological Process | fatty acid beta-oxidation | 9 | 453 | 15 | 4696 | 1.98E-06 | Decreasing |

| GO Biological Process | fatty acid catabolic process | 7 | 453 | 14 | 4696 | 1.40E-04 | Decreasing |

| GO Biological Process | autophagy | 7 | 453 | 17 | 4696 | 6.11E-04 | Decreasing |

| GO Biological Process | hyperosmotic response | 3 | 453 | 3 | 4696 | 8.92E-04 | Decreasing |

| GO Cellular Component | peroxisomal matrix | 12 | 412 | 30 | 4148 | 1.29E-05 | Decreasing |

| GO Cellular Component | integral to peroxisomal membrane | 4 | 412 | 4 | 4148 | 9.61E-05 | Decreasing |

| GO Molecular Function | zinc ion binding | 43 | 470 | 219 | 4823 | 4.04E-06 | Decreasing |

| GO Molecular Function | specific RNA polymerase II transcription factor activity | 7 | 470 | 17 | 4823 | 6.51E-04 | Decreasing |

| GO Molecular Function | two-component sensor activity | 6 | 470 | 13 | 4823 | 7.84E-04 | Decreasing |

| GO Biological Process | translation | 107 | 718 | 149 | 4696 | 2.50E-56 | Increasing |

| GO Cellular Component | cytosolic large ribosomal subunit (sensu Eukaryota) | 42 | 689 | 45 | 4148 | 5.33E-30 | Increasing |

| GO Cellular Component | cytosolic small ribosomal subunit (sensu Eukaryota) | 28 | 689 | 35 | 4148 | 1.93E-16 | Increasing |

| GO Molecular Function | structural constituent of ribosome | 96 | 711 | 118 | 4823 | 9.53E-61 | Increasing |

| 16 Hour | |||||||

| GO Biological Process | fatty acid beta-oxidation | 8 | 237 | 15 | 4696 | 1.77E-07 | Decreasing |

| GO Biological Process | N-acetylglucosamine catabolic process | 4 | 237 | 5 | 4696 | 3.04E-05 | Decreasing |

| GO Cellular Component | peroxisomal matrix | 10 | 219 | 30 | 4148 | 1.62E-06 | Decreasing |

| GO Cellular Component | peroxisome | 6 | 219 | 23 | 4148 | 9.56E-04 | Decreasing |

| GO Molecular Function | electron transporter activity | 4 | 249 | 10 | 4823 | 1.14E-03 | Decreasing |

| GO Biological Process | translation | 88 | 590 | 149 | 4696 | 4.78E-43 | Increasing |

| GO Cellular Component | cytosolic large ribosomal subunit (sensu Eukaryota) | 42 | 563 | 45 | 4148 | 9.14E-34 | Increasing |

| GO Cellular Component | cytosolic small ribosomal subunit (sensu Eukaryota) | 29 | 563 | 35 | 4148 | 2.71E-20 | Increasing |

| GO Molecular Function | structural constituent of ribosome | 81 | 591 | 118 | 4823 | 8.01E-48 | Increasing |

The number of genes with significant changes at 16 h was 1235 with 855 increasing and 380 decreasing. The gene with the largest decrease between the two time points was isocitrate lyase with a decrease of 172.8-fold. This was followed by a hypothetical protein (AFUA_1G01490) with a decrease of 158.5-fold, cytochrome P450 monooxygenase with a decrease of 150.8-fold, and the same monosaccharide transporter as T8 with a decrease of 142.0-fold. A total of 8 genes had decreased fold changes greater than 100 (Table II and supplementary Table S4). The largest change was seen in endochitosanase with an increase of 115.3-fold compared with T0. Other genes such as an MFS monosaccharide transporter had an increase in gene expression of 98.5-fold, secreted dipeptidyl peptidase had an increase of 93.4-fold and the allergen AspF4 had an increase of 89.2-fold (Table II and supplementary Table S4). The gene ontology information obtained for the 380 decreasing genes indicates that the favored biological process is again fatty acid β-oxidation as well as N-acetylglucosamine catabolism. The cellular component for these processes is the peroxisome and the peroxisomal matrix with the favored molecular function being electron transporter activity (supplementary Table S5). For the 855 increasing genes, the most highly favored biological process is still translation along with ATP synthesis coupled proton transport as well as mitochondrial electron transport. These indicate a large push toward ATP generation through the electron transport chain (supplementary Table S6).

Proteomic/Genomic Comparison

A total of 231 proteins were identified with high confidence using the gel-free system of iTRAQ at four time points: 0 h, 4 h, 8 h, and 16 h. To compare the changes in the proteome with changes in the genome, microarray analysis was evaluated at 8 and 16 h of growth relative to T0. A total of 1871 genes changed twofold or more at 8 h and 1235 changed twofold or more at 16 h. At the 8 h time point, 57 combinations of genes and proteins with significant changes were found, but only 22 had changes in the same direction (Table III and supplementary Table S7). These include heat shock proteins Hsp30/Hsp42 with a decrease in protein level by 28.6-fold and a decrease in gene level by 25.5-fold. Glutamine synthetase had a small change in protein level (down 3.5-fold) but a large change in gene expression level (down 20.6 fold). Of the 17 proteins that showed significant increases at 8 h, 16 were also identified as significantly increasing by microarray (Table III and supplementary Table S7); 12 of these proteins were ribosomal proteins. The largest change seen by proteomics in these proteins was an increase of 2.6-fold in the 40S ribosomal protein S15, but the largest change by microarray was 15.3-fold in the nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha. Some protein and gene combinations have values that differ vastly such as flavohemoprotein, which had a decrease in protein level of 3.3-fold but an increase in gene level of 14.2-fold. The same pattern was observed with the pyruvate peroxiredoxin pmp20, which has a protein decrease of 2.2-fold but a gene increase of 9.3-fold. Other proteins that showed significant changes in expressed protein such as abr2, Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase, rodA, and the putative uncharacterized protein (AFUA_8G00630), all with decreases of greater than 10-fold, were not detected by microarray analysis at the time points evaluated.

Table III. Comparison of protein vs. gene expression values at 8 hours (twofold or greater). NI, Not Identified.

| UniProt ID | ORF Name | Gene Name | Common Name of Target | Molecular Weight | Average 8 Hour Protein Fold Change | Average 8 Hour Gene Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q4WYW9 | AFUA_3G14540 | Heat shock protein Hsp30/Hsp42, putative | 20 kDa | −28.6 | −25.5 | |

| Q9UVW1 | AFUA_2G17530 | abr2 | Brown 2 | 65 kDa | −25.2 | NI |

| Q9Y8D9 | AFUA_5G09240 | sodC | Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | 16 kDa | −19.4 | NI |

| P41746 | AFUA_5G09580 | rodA | Hydrophobin | 16 kDa | −18.4 | NI |

| Q4WB08 | AFUA_8G00630 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 37 kDa | −15.8 | NI | |

| Q4WP70 | AFUA_4G08240 | Zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenase, putative | 37 kDa | −12.4 | −2.3 | |

| Q4WXX9 | AFUA_3G11070 | pdcA | Pyruvate decarboxylase | 63 kDa | −6.8 | NI |

| Q4WP18 | AFUA_4G07710 | Pyruvate carboxylase, putative | 131 kDa | −6.8 | 2.5 | |

| Q4WCP3 | AFUA_6G01940 | Dienelactone hydrolase family protein | 35 kDa | −5.2 | −2.7 | |

| Q4X1G7 | AFUA_2G10030 | Actin cytoskeleton protein (VIP1), putative | 28 kDa | −4.0 | NI | |

| Q4WMB9 | AFUA_6G10450 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 27 kDa | −3.7 | NI | |

| Q4WQK3 | AFUA_4G13120 | Glutamine synthetase | 40 kDa | −3.5 | −20.6 | |

| Q4W9X3 | AFUA_4G03410 | Flavohemoprotein | 46 kDa | −3.3 | 14.2 | |

| Q4WDJ0 | AFUA_6G04920 | NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase AciA/Fdh | 46 kDa | −3.1 | NI | |

| Q96X30 | AFUA_6G06770 | enoA | Enolase | 47 kDa | −3.1 | 6.7 |

| Q4WV46 | AFUA_5G10780 | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | 41 kDa | −3.0 | 2.6 | |

| Q4WH99 | AFUA_2G06150 | Protein disulfide isomerase Pdi1, putative | 56 kDa | −3.0 | 3.0 | |

| Q4WW75 | AFUA_5G14680 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 25 kDa | −2.9 | NI | |

| Q7Z7W6 | AFUA_8G01670 | katG | Catalase-peroxidase | 84 kDa | −2.9 | −2.0 |

| Q4WVV5 | AFUA_5G13450 | Triosephosphate isomerase | 28 kDa | −2.9 | 3.8 | |

| Q4WEG3 | AFUA_5G02910 | NAP family protein | 41 kDa | −2.8 | NI | |

| Q4WI29 | AFUA_6G06750 | 14-3-3 family protein | 29 kDa | −2.8 | 3.5 | |

| Q4WUP8 | AFUA_5G09230 | Transaldolase | 35 kDa | −2.7 | NI | |

| Q4WTZ9 | AFUA_5G06680 | 4-aminobutyrate transaminase GatA | 55 kDa | −2.7 | 6.0 | |

| Q4WN06 | AFUA_6G08050 | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating | 56 kDa | −2.5 | 2.1 | |

| Q4X1J1 | AFUA_2G09790 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 61 kDa | −2.3 | 3.5 | |

| Q4WDM0 | AFUA_6G05210 | Malate dehydrogenase, NAD-dependent | 35 kDa | −2.3 | 2.1 | |

| Q4X1G3 | AFUA_2G10070 | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, large subunit | 129 kDa | −2.3 | 4.5 | |

| Q4WN39 | AFUA_6G07720 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase AcuF | 67 kDa | −2.3 | −2.8 | |

| Q4WTX0 | AFUA_5G06390 | Adenosine kinase, putative | 37 kDa | −2.3 | 5.1 | |

| Q4WYW4 | AFUA_3G14490 | Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | 56 kDa | −2.3 | NI | |

| Q4WJV9 | AFUA_1G04620 | Alcohol dehydrogenase, zinc-containing, putative | 38 kDa | −2.2 | 2.4 | |

| Q4WM07 | AFUA_6G11620 | Formyltetrahydrofolate deformylase, putative | 32 kDa | −2.2 | 2.7 | |

| Q4WNY2 | AFUA_4G07360 | Cobalamin-independent methionine synthase MetH/D | 87 kDa | −2.2 | 3.5 | |

| O43099 | AFUA_6G02280 | pmp20 | Putative peroxiredoxin pmp20 | 18 kDa | −2.2 | 9.3 |

| Q4X164 | AFUA_2G11060 | Acyl CoA binding protein family | 17 kDa | −2.1 | 4.8 | |

| Q4WSV7 | AFUA_1G11480 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 20 kDa | −2.1 | 3.3 | |

| Q4WA70 (+1) | AFUA_7G00250 | Tubulin beta chain | 50 kDa | −2.1 | NI | |

| Q4WSA0 | AFUA_1G13500 | Transketolase TktA | 75 kDa | −2.0 | 3.3 | |

| Q4WY39 | AFUA_3G11690 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, class II | 40 kDa | −2.0 | 3.0 | |

| Q4WLQ2 | AFUA_6G12720 | 40S ribosomal protein S29, putative | 9 kDa | 2.0 | 9.2 | |

| Q4WSZ2 | AFUA_1G11130 | 60S ribosomal protein L6 | 22 kDa | 2.0 | 6.3 | |

| Q4WTM9 | AFUA_5G05450 | rps1 | 40S ribosomal protein S1 | 29 kDa | 2.0 | 8.5 |

| Q4WIE3 | AFUA_2G02150 | 40S ribosomal protein S10a | 13 kDa | 2.0 | 9.5 | |

| Q4WZH8 | AFUA_2G16880 | 60S ribosomal protein L37a | 10 kDa | 2.0 | 11.2 | |

| Q4WMV5 | AFUA_6G08580 | fpr4 | FK506-binding protein 4 | 53 kDa | 2.1 | NI |

| Q4W9S8 | AFUA_4G03860 | nip1 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit C | 98 kDa | 2.1 | 3.0 |

| Q4WD81 | AFUA_6G03820 | egd2 | Nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha | 22 kDa | 2.1 | 15.3 |

| Q4WK14 | AFUA_1G04070 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF-5A | 21 kDa | 2.1 | 5.9 | |

| Q4WLQ8 | AFUA_6G12660 | 40S ribosomal protein S10b | 18 kDa | 2.1 | 9.2 | |

| Q4WVI1 | AFUA_5G12180 | Ran-specific GTPase-activating protein 1, putative | 28 kDa | 2.1 | 4.6 | |

| Q4WPX5 | AFUA_4G10800 | 40S ribosomal protein S6 | 27 kDa | 2.1 | 9.6 | |

| Q4WCU3 | AFUA_6G02440 | 60S ribosomal protein L24a | 18 kDa | 2.2 | 12.5 | |

| Q4WWR1 | AFUA_3G06760 | Ribosomal protein L37 | 18 kDa | 2.2 | 6.2 | |

| Q4X205 | AFUA_2G08130 | 60S ribosomal protein L44 | 12 kDa | 2.2 | 10.6 | |

| Q4X279 | AFUA_2G07380 | Ribosomal protein L18 | 21 kDa | 2.3 | 7.5 | |

| Q4X1G1 | AFUA_2G10090 | 40S ribosomal protein S15, putative | 18 kDa | 2.6 | 8.3 |

At the 16 h time point, 18 protein/gene combinations were observed in which both proteins and genes changed twofold or greater (Table IV and supplementary Table S8). Of these, 12 combinations showed a given protein and gene changing in the same direction (six decreasing and six increasing.) None of the nine proteins with the largest decreases by proteomics were identified in the microarray analysis suggesting a rapid turnover of mRNA. Decreasing proteins with a genomic counterpart included the nucleolin protein Nsr1 with a protein decrease of threefold and a gene decrease of 2.8-fold, ABC transporter Arb1 with protein fold decrease of 2.2 and gene decrease of 4.7-fold, Asn2 for asparagine synthetase with a protein decrease of 2.1-fold and gene decrease of 2.2-fold, and the RNA helicase ded1 with protein fold decrease of 2.1 and gene decrease of 8.4-fold. A similar pattern of larger changes in gene expression than changes in relative protein level was also seen at 16 h. The translation elongation factor eEF-3 showed a gene change 5.7 times that of the protein change (12.5 for the gene and 2.2 for the protein) whereas the glutamine synthetase showed a gene change 7.2 times that of the protein change (20.9 fold for the gene versus 2.9 fold for the protein). Of the six proteins that increased, three were putative uncharacterized proteins (Table IV and supplementary Table S8). AFUA_5G14680 increased 2.1-fold in the protein and 24.3-fold in the gene; AFUA_8G05600 had a 2.5-fold protein expression increase with a 32.9-fold gene expression increase, and AFUA_3G06460 had a 2.5-fold increase in protein with an 8.9-fold increase in gene expression. Other combinations included a 57 kDa immunogenic protein (AFUA_4G12450), tropomyosin, and the same GTPase activating protein as T8. The protein with the largest change was cytochrome c with an increase of 2.6-fold, but the gene was not detected above baseline in the final analysis.

Table IV. Comparison of protein vs. gene expression values at 16 hours (twofold or greater). NI, Not Identified.

| UniProt ID | ORF Name | Gene Name | Common Name of Target | Molecular Weight | Average 16 Hour Protein Fold Change | Average 16 Hour Gene Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q9UVW1 | AFUA_2G17530 | abr2 | Brown 2 | 65 kDa | −24.3 | NI |

| Q4WB08 | AFUA_8G00630 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 37 kDa | −17.2 | NI | |

| P41746 | AFUA_5G09580 | rodA | Hydrophobin | 16 kDa | −10.9 | NI |

| Q4WYW9 | AFUA_3G14540 | Heat shock protein Hsp30/Hsp42, putative | 20 kDa | −10.6 | NI | |

| Q4WP18 | AFUA_4G07710 | Pyruvate carboxylase, putative | 131 kDa | −7.0 | NI | |

| Q9Y8D9 | AFUA_5G09240 | sodC | Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | 16 kDa | −6.2 | NI |

| Q4WP70 | AFUA_4G08240 | Zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenase, putative | 37 kDa | −6.2 | NI | |

| Q4WEG3 | AFUA_5G02910 | NAP family protein | 41 kDa | −4.2 | NI | |

| Q4WTZ9 | AFUA_5G06680 | 4-aminobutyrate transaminase GatA | 55 kDa | −3.8 | NI | |

| Q4WX01 | AFUA_3G07710 | Nucleolin protein Nsr1, putative | 58 kDa | −3.0 | −2.8 | |

| Q4X1G3 | AFUA_2G10070 | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, large subunit | 129 kDa | −2.9 | NI | |

| Q4WQK3 | AFUA_4G13120 | Glutamine synthetase | 40 kDa | −2.9 | −20.9 | |

| Q4WCP3 | AFUA_6G01940 | Dienelactone hydrolase family protein | 35 kDa | −2.8 | 2.8 | |

| Q96X30 | AFUA_6G06770 | enoA | Enolase | 47 kDa | −2.6 | 5.7 |

| Q4WYW4 | AFUA_3G14490 | Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | 56 kDa | −2.5 | NI | |

| Q4WMV5 | AFUA_6G08580 | fpr4 | FK506-binding protein 4 | 53 kDa | −2.4 | NI |

| Q4WJM1 | AFUA_1G05500 | 40S ribosomal protein S12 | 16 kDa | −2.3 | 6.8 | |

| Q4WVV5 | AFUA_5G13450 | Triosephosphate isomerase | 28 kDa | −2.3 | 3.4 | |

| Q4WM07 | AFUA_6G11620 | Formyltetrahydrofolate deformylase, putative | 32 kDa | −2.3 | NI | |

| Q4WGN6 | AFUA_7G05660 | Translation elongation factor eEF-3, putative | 118 kDa | −2.2 | −12.5 | |

| Q4WN06 | AFUA_6G08050 | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating | 56 kDa | −2.2 | NI | |

| Q4WU32 | AFUA_5G07020 | Ribosome biogenesis ABC transporter Arb1, putative | 70 kDa | −2.2 | −4.7 | |

| Q4WNT6 | AFUA_4G06900 | Asparagine synthetase Asn2, putative | 72 kDa | −2.1 | −2.2 | |

| Q4WP13 | AFUA_4G07660 | ded1 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase ded1 | 72 kDa | −2.1 | −8.4 |

| Q4WTX0 | AFUA_5G06390 | Adenosine kinase, putative | 37 kDa | −2.0 | 6.7 | |

| Q873W8 | AFUA_1G09440 | rps23 | 40S ribosomal protein S23 | 16 kDa | −2.0 | 5.9 |

| Q4WW75 | AFUA_5G14680 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 25 kDa | 2.1 | 24.3 | |

| Q4WQD6 | AFUA_4G12450 | 57 kDa immunogenic protein | 57 kDa | 2.1 | 5.7 | |

| Q4WG92 | AFUA_7G04210 | Tropomyosin, putative | 18 kDa | 2.2 | 11.5 | |

| Q4WN39 | AFUA_6G07720 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase AcuF | 67 kDa | 2.4 | −7.6 | |

| Q4WVI1 | AFUA_5G12180 | Ran-specific GTPase-activating protein 1, putative | 28 kDa | 2.5 | 4.2 | |

| Q4WC61 | AFUA_8G05600 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 9 kDa | 2.5 | 32.9 | |

| Q4WWN1 | AFUA_3G06460 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 16 kDa | 2.5 | 8.9 | |

| Q4X0L0 | AFUA_2G13110 | Cytochrome c | 26 kDa | 2.6 | NI |

DISCUSSION

The A. fumigatus proteome is complex and highly dynamic during the early stages of development following conidial germination. A classical two-dimensional gel approach to evaluate changes in the proteome during early development suffers from an inherent lack of sensitivity. This issue was seen with the mapping of the proteome of conidia by Teutschbein et al. (18) in which one two-dimensional gel was unable to resolve all protein spots. To increase the relative resolving power this group used two-dimensional gels with narrow pI ranges, but this lead to many spots being identified multiple times. To circumvent these problems and improve resolution, a gel-free system of iTRAQ was used to identify 461 proteins, more than Tuetschbein et al., along with quantitative measurements of the protein amount over several time points, which is unique to this study. The time points chosen for this study were selected because they are at critical early development stages for the cell including the swelling of conidia, the formation of a germ tube and a culture that has become more mature. These developmental stages elicit protein signatures that portend early A. fumigatus infection. At the earliest time point, T4, 15 proteins showed a decrease of twofold or greater indicating that these proteins are either present in the conidium itself or are transcribed and translated at a very early time point. Of the 40 most abundant proteins in conidia by two-dimensional analysis, 30 were also present in our analysis and 24 were high confidence proteins (two unique peptides of 95% confidence, protein identification at least 99%). Some proteins are expected to decrease and therefore serve as a validation of the approach including RodA which forms the rodlet layer on the surface of conidia (13) and decreased by 10.6-fold. The abr2 gene encoding the final enzyme in the melanin biosynthetic pathway decreased by 10.2-fold at 4 h and continued to decrease to over 25-fold at 8 h and 24.3 fold at 16 h. The proteins that increase at T4, as well as the other time points, suggest a large increase in ribosomal genes consistent with the increases in translation necessary for growth. These proteins and their pathways, including cytochrome C, the 57 kDa immunogenic protein, as well as members of the TCA cycle, are potential targets for new antifungals or possible biomarkers of active infection.

Previously it was reported that a total of 63 proteins decreased in mycelia versus conidia while 38 increased (18). Consistent with these results, we found 65.7% (25/38) of the reported proteins that increased; yet only 25.4% (16/63) of decreasing proteins. Of the proteins that were identified, the trend behavior is consistent although the absolute fold changes observed are different, as expected. Certain signature proteins such as RodAp showed a similar pattern decreasing by 10.9-fold in this study and 27.3-fold and 21.5-fold previously (18). Some proteins showed a poor correlation such as the NAD-dependant formate dehydrogenase AciA/Fdh, which remained consistent in our time course whereas a large decrease of 44.4, 9.5, and 4.5-fold was observed in the two-dimensional study (18). This may reflect the nutritional source of the culture. The current study had all cultures grown in a rich YPD medium whereas Teutschbein et al. (18) grew their cultures in a more defined AMM supplemented with 50 mm glucose. Of the 41 common proteins found between the two studies, over 50% (22) changes were in the same direction. Overall these data suggest that both gel free and gel based systems yield important information about expressed proteins during growth and development.

To provide a more comprehensive view of the early development of A. fumigatus a whole genome microarray analysis was performed to assess the relationship between gene expression and protein abundance. This combined analysis is unique to this study in Aspergillus fumigatus development. Analysis of the genomic and proteomic profiles reflects a dynamic cell undergoing a rapid transfer toward aerobic growth and development. The T8 microarray data and the iTRAQ agree insomuch as the biological process of translation shows the most significant increase and 70.5% (12/17) of the proteins increasing the most are ribosomal. The microarray data of the genes that are down-regulated also shows that the synthesis of fatty acids is a critical early process at this time suggesting that they may be possible biomarker or antifungal targets. At T16, similar trends are shown with the data indicating that translation is still very active as is fatty acid synthesis. N-acetylglucosamine synthesis is also up-regulated, which is consistent with chitin being integrated into the rapidly expanding cell wall for structural integrity. One previous study also looked at the changes in expression during the exit from dormancy of spores, and although a full microarray was not used many of the results and consistent with our data (8). The study by Lamarre et al. (8) used time points earlier than those chosen in the current study (8 and 16 h in the current study versus 30, 60, and 90 min post inoculation in the previous study). In that study, an array of 3000 genes was utilized compared with our full genome microarray with over 9000 genes represented. It was reported that the processes of protein, amino acid, and protein complex synthesis as well as ribosome biogenesis are increasing consistent with our microarray indicating that translation is the favored biological process during early development.

Another process found to be up-regulated in the current study was that of aerobic respiration. The GO information at 8 h demonstrated that 15 genes identified were involved in this process including three subunits of the cytochrome C oxidase complex along with mitochondrial large ribosomal proteins. This is in agreement with previous studies that demonstrate that the process of aerobic respiration is required for A. fumigatus growth (31). This process was also shown to be up-regulated by microarray at 16 h demonstrating that aerobic respiration is still active during mature cultures with three subunits of the cytochrome C oxidase family increasing by at least 7.6-fold. The ubiquinol-cytochrome C reductase complex also had 5 members increased at 16 h.

Validation of Findings

As a way to help validate the proteomic findings in this study, we have compared recent proteomic findings from a study involving inhibition of cell growth with the echinocandin drug caspofungin (22). When caspofungin is added to a culture of A. fumigatus, it acts as a fungistatic agent, only allowing the formation of “rosette structures” (22). Therefore if a certain protein decreases in the presence of caspofungin and increases during normal development, the caspofungin data can serve as an indirect validation for the development data. When the data from this study was compared with the previous proteomic research performed by Cagas et al. (22), there was overlap in many of the proteins observed. Of the 461 total proteins in this study, 216 were identified in two iTRAQs that were run with a caspofungin sensitive and resistant strain in the presence and absence of the drug. Of the 231 high confidence proteins identified in this study, 137 proteins were found to be in common with the previous research. These 137 common proteins were analyzed for possible information on the efficacy of current caspofungin treatment. Proteins involved electron transport such as cytochrome c and the cytochrome c subunit Va and Vb decrease by 3.48-, 2.00-, and 1.52-fold respectively in the presence of caspofungin, but increase 2.56-, 1.71-, and 1.63-fold during normal development at 16 h. This same pattern hold true for enzymes involved in glycolysis such as phosphoglycerate kinase which increase 1.66-fold at 16 h and decreases 3.48-fold when exposed to caspofungin. The 57 kDa immunogenic protein which increased 2.15-fold during development and decreased 1.62-fold after exposure to caspofungin is also believed to be involved in metabolism and amino acid biosynthesis (32).

Overall, the current study provides the most comprehensive proteomic and genomic signature of A. fumigatus during germination and early development, which contributes to the overall understanding of this human pathogen. The results discovered in this study can impact the fields of fungal development, antifungal drug discovery, biomarker assessment as well as Aspergillus pathogenesis. These processes may be used for the discovery and assessment of novel biomarkers of active infection, as well as possible new therapeutic targets. It also reveals a pathogen that is gearing up for rapid growth by building translation machinery, generating ATP, and is very much committed to aerobic metabolism.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steven Park and Guillermo Garcia-Effron for their helpful discussions and suggestions and Yanan Zhao and Cristina Jimenez-Ortigosa for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Natalie Fedorova for her assistance using the TMEV software.

Footnotes

* This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI069397 to D. S. P.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 to S8.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 to S8.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- iTRAQ

- isobaric tagging for relative and absolute quantitation

- TEAB

- triethylammonium bicarbonate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Latgé J. P. (1999) Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12, 310–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Denning D. W. (1998) Invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26, 781–803; quiz 804–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marr K. A., Patterson T., Denning D. (2002) Aspergillosis. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and therapy. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 16, 875–894, vi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feldmesser M. (2006) Role of neutrophils in invasive aspergillosis. Infect. Immun. 74, 6514–6516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Segal B. H. (2009) Aspergillosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1870–1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barhoom S., Sharon A. (2004) cAMP regulation of “pathogenic” and “saprophytic” fungal spore germination. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41, 317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harris S. D., Momany M. (2004) Polarity in filamentous fungi: moving beyond the yeast paradigm. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41, 391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lamarre C., Sokol S., Debeaupuis J. P., Henry C., Lacroix C., Glaser P., Coppée J. Y., Francois J. M., Latgé J. P. (2008) Transcriptomic analysis of the exit from dormancy of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. BMC Genomics 9, 417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Asif A. R., Oellerich M., Amstrong V. W., Riemenschneider B., Monod M., Reichard U. (2006) Proteome of conidial surface associated proteins of Aspergillus fumigatus reflecting potential vaccine candidates and allergens. J. Proteome Res. 5, 954–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chai L. Y., Netea M. G., Sugui J., Vonk A. G., van de Sande W. W., Warris A., Kwon-Chung K. J., Jan Kullberg B. (2009) Aspergillus fumigatus Conidial Melanin Modulates Host Cytokine Response. Immunobiology 215, 915–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pihet M., Vandeputte P., Tronchin G., Renier G., Saulnier P., Georgeault S., Mallet R., Chabasse D., Symoens F., Bouchara J. P. (2009) Melanin is an essential component for the integrity of the cell wall of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. BMC Microbiol. 24, 177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Youngchim S., Morris-Jones R., Hay R. J., Hamilton A. J. (2004) Production of melanin by Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Med. Microbiol. 53, 175–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aimanianda V., Bayry J., Bozza S., Kniemeyer O., Perruccio K., Elluru S. R., Clavaud C., Paris S., Brakhage A. A., Kaveri S. V., Romani L., Latgé J. P. (2009) Surface hydrophobin prevents immune recognition of airborne fungal spores. Nature 460, 1117–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paris S., Debeaupuis J. P., Crameri R., Carey M., Charlès F., Prévost M. C., Schmitt C., Philippe B., Latgé J. P. (2003) Conidial hydrophobins of Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 1581–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thau N., Monod M., Crestani B., Rolland C., Tronchin G., Latgé J. P., Paris S. (1994) Rodletless mutants of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 62, 4380–4388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gautam P., Sundaram C. S., Madan T., Gade W. N., Shah A., Sirdeshmukh R., Sarma P. U. (2007) Identification of novel allergens of Aspergillus fumigatus using immunoproteomics approach. Clin. Exp. Allergy 37, 1239–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gravelat F. N., Doedt T., Chiang L. Y., Liu H., Filler S. G., Patterson T. F., Sheppard D. C. (2008) In vivo analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus developmental gene expression determined by real-time reverse transcription-PCR. Infect. Immun. 76, 3632–3639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Teutschbein J., Albrecht D., Pötsch M., Guthke R., Aimanianda V., Clavaud C., Latgé J. P., Brakhage A. A., Kniemeyer O. (2010) Proteome profiling and functional classification of intracellular proteins from conidia of the human-pathogenic mold Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Proteome Res. 9, 3427–3442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beranova-Giorgianni S. (2003) Proteome analysis by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry: strengths and limitations. Trac-Trend Anal. Chem. 22, 273–281 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ross P. L., Huang Y. N., Marchese J. N., Williamson B., Parker K., Hattan S., Khainovski N., Pillai S., Dey S., Daniels S., Purkayastha S., Juhasz P., Martin S., Bartlet-Jones M., He F., Jacobson A., Pappin D. J. (2004) Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 1154–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zieske L. R. (2006) A perspective on the use of iTRAQ reagent technology for protein complex and profiling studies. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 1501–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cagas S. E., Jain M. R., Li H., Perlin D. S. (2011) Profiling the Aspergillus fumigatus proteome in response to caspofungin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 146–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Niki Y., Bernard E. M., Edwards F. F., Schmitt H. J., Yu B., Armstrong D. (1991) Model of recurrent pulmonary aspergillosis in rats. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29, 1317–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saeed A. I., Sharov V., White J., Li J., Liang W., Bhagabati N., Braisted J., Klapa M., Currier T., Thiagarajan M., Sturn A., Snuffin M., Rezantsev A., Popov D., Ryltsov A., Kostukovich E., Borisovsky I., Liu Z., Vinsavich A., Trush V., Quackenbush J. (2003) TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques 34, 374–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hosack D. A., Dennis G., Jr., Sherman B. T., Lane H. C., Lempicki R. A. (2003) Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol. 4, R70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]