Abstract

Background:

Distal radial fractures affect an estimated 80,000 elderly Americans each year. Although the use of internal fixation for the treatment of distal radial fractures is becoming increasingly common, there have been no population-based studies to explore the dissemination of this technique. The aims of our study were to determine the current use of internal fixation for the treatment of distal radial fractures in the Medicare population and to examine regional variations and other factors that influence use of this treatment. We hypothesized that internal fixation of distal radial fractures would be used less commonly in male and black populations compared with other populations because the prevalence of osteoporosis is lower in these populations, and that use of internal fixation would be correlated with the percentage of the patients who were treated by a hand surgeon in a particular region.

Methods:

We performed an analysis of complete 2007 Medicare data to determine the percentage of distal radial fractures that were treated with internal fixation in each hospital referral region. We then analyzed the association of patient and physician factors with the type of fracture treatment received, both nationally and within each hospital referral region.

Results:

We identified 85,924 Medicare beneficiaries with a closed distal radial fracture who met the inclusion criteria, and 17.0% of these patients were treated with internal fixation. Fractures were significantly less likely to be treated with internal fixation in men than in women (odds ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.80 to 0.89) and in black patients than in white patients (odds ratio, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.65 to 0.85). Patients were more likely to be treated with internal fixation rather than with another treatment if they were treated by a hand surgeon than if they were treated by an orthopaedic surgeon who was not a hand surgeon (odds ratio, 2.49; 95% confidence interval, 2.29 to 2.70). Use of internal fixation ranged from 4.6% to 42.1% (nearly a ten-fold difference) among hospital referral regions. The percentage of patients treated with internal fixation within a hospital referral region was positively correlated with the percentage of patients in that region who were treated by a hand surgeon (correlation coefficient, 0.34; p < 0.0001).

Conclusions:

The use of internal fixation for the treatment of a distal radial fracture differs widely among geographical regions and patient populations. Such variations highlight the need for improved comparative-effectiveness data to guide the treatment of this fracture.

Medicare beneficiaries sustain approximately 80,000 distal radial fractures annually1. As the second most common type of fracture experienced by these patients2,3, distal radial fractures contribute considerably to the estimated $1.1 billion spent annually in this population to treat fractures associated with osteoporosis3. The number of distal radial fractures, and the resulting cost of treatment, will likely continue to increase as the number of elderly Americans increases4. These fractures have traditionally been treated conservatively with closed reduction and casting. However, fractures treated in this manner are prone to collapse and malunion because elderly individuals often have weak, osteoporotic bone5,6. Open reduction and internal fixation of distal radial fractures, a common treatment for younger adults that provides better fracture stabilization, is being increasingly and successfully used in the elderly population as well7. For instance, previous studies have shown that use of the volar locking plating system (VLPS) is increasing in the Medicare population, in which osteoporosis is common1,8-10. Percutaneous pinning and external fixation are also options for the treatment of distal radial fractures in elderly patients. Although we are aware of no formal studies comparing the costs of different distal radial fracture treatments in the U.S., the cost differential between a relatively simple treatment such as casting and a treatment such as internal fixation, which is more equipment and labor-intensive, is likely to be substantial11. A recently published study by Fanuele et al. that analyzed the treatment of distal radial fractures according to hospital referral regions (as defined in The Dartmouth Atlas of Musculoskeletal Health Care) revealed the existence of wide regional variations in the use of these treatment methods12. Such marked regional variations may result from variations in injury pattern, patient preference, or the surgeon's opinion regarding the optimal management of the injury or condition13-15.

Only 3% of distal radial fractures in the Medicare population were treated with open reduction and internal fixation in 1996, but by 2005 the percentage had grown to 16%1. This growth has been rapid, with a doubling of the percentage during the five-year period from 1999 to 200412. This increase in the use of internal fixation techniques for the treatment of a distal radial fracture may create uncertainty regarding the optimal treatment for elderly patients in the U.S., as an increasing number of surgeons embrace the operative approach despite the lack of high-level evidence demonstrating that the outcomes of this treatment are superior to those of conservative treatment in the elderly. We built on the study by Fanuele et al. by examining the national and regional use of internal fixation procedures for the treatment of distal radial fractures in the Medicare population through 2007 and analyzing the patient and physician factors associated with treatment with internal fixation. We hypothesized that internal fixation would be used less commonly in men than in women, and less commonly in black patients than in white patients, because the prevalence of osteoporosis is lower in these populations16-18. We also examined regional variations in the use of internal fixation in order to evaluate whether particular regions of the country are adopting this new technology to a greater extent than others. In particular, we hypothesized that use of internal fixation in a particular region would be related to the percentage of patients treated by a hand surgeon, since these surgeons will have received training that placed a greater emphasis on surgical techniques and will have greater familiarity with this technique compared with other orthopaedic surgeons.

Materials and Methods

We obtained complete (100%) 2007 data relating to distal radial fractures from the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). This included the enrollment/denominator file as well as all claims from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Reviews (MedPAR) file (for Medicare Part A) and the Outpatient and Carrier files (for Medicare Part B) that involved ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification) codes for fractures of the radius and/or ulna (813.00 through 813.93). We excluded patients whose claims indicated the presence of bone or metastatic cancer. We also excluded patients who were enrolled in health maintenance organizations and those who were not enrolled in both Medicare Part A and Part B for the entirety of 2007. Because beneficiaries who qualify for Medicare prior to reaching sixty-five years of age differ greatly from patients who qualify for Medicare upon reaching sixty-five years of age19, we excluded patients who were less than sixty-five years of age on January 1, 2007. We also excluded patients over the age of ninety-nine years.

We further limited our analysis to patients whose claims listed one of the five ICD-9-CM codes most likely to represent a diagnosis of closed distal radial fracture: 813.40 (fracture, lower end of forearm, unspecified), 813.41 (Colles fracture), 813.42 (other fracture of distal end of radius [alone]), 813.44 (fracture, radius with ulna, lower end), and 813.45 (torus fracture of radius [alone]). The patient's claim was also required to list one of fourteen CPT (Current Procedural Terminology) codes indicating treatment of a distal radial fracture with external fixation (20690 or 20692), closed treatment (25600, 25605, 29065, 29075, 29085, 29105, 29125, or 29126), percutaneous pinning (25606), or internal fixation (25607, 25608, or 25609).

Finally, we included patients only if they had been treated within two weeks of diagnosis. Patients who were diagnosed with one of the relevant ICD-9-CM codes but did not have any claims for one of the relevant CPT codes were removed from the analysis cohort. A separate examination of the data for these patients showed that most of them had sustained a distal radial fracture in 2006 and were returning for follow-up treatment in 2007. The two-week period also allowed us to isolate the definitive treatment received. It is common for patients with a fracture to be treated with a splint or cast when they present to an emergency department or the office of a primary care physician, then be referred to a specialist for definitive treatment. Therefore, in order to ensure that we were recording only this definitive treatment, we developed a hierarchy of treatment categories in order of decreasing invasiveness: internal fixation was the most invasive, followed by percutaneous pinning, then external fixation, and finally closed treatment. Each claim that included a diagnosis of distal radial fracture was examined for relevant treatment during the two-week period following diagnosis. If more than one treatment was reported, only the most invasive treatment was recorded as the definitive treatment. We established the two-week limit on the basis of our clinical experience treating distal radial fractures; nearly all of our patients receive definitive treatment within two weeks of injury. We also confirmed that the two-week limit was appropriate in our study cohort by calculating the frequency with which the definitive treatment changed when a limit of one, two, three, or four weeks following diagnosis was used. The two-week limit prevented us from overestimating the number of patients receiving closed treatment as the definitive treatment.

In addition to the ICD-9-CM and CPT codes associated with the patient diagnoses and the interventions received during the visit, each claim included unique identifiers that could be linked to the Medicare denominator file to determine the patient's sex, age, race, and postal code. We analyzed patient age with the use of five-year intervals, and we analyzed race with the use of black, white, and “other” groups. We used an adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index20 to calculate a patient comorbidity score on the basis of inpatient claims (in the MedPAR file) and outpatient claims (in the Outpatient and Carrier files) dated prior to the date of diagnosis of the distal radial fracture. We used previously published socioeconomic status scores for each postal code in the U.S.21 and the postal code of the patient's residence (obtained with use of the denominator file) to determine a socioeconomic status score for the patient22.

Because many of the distal radial fractures that occur in elderly women are the result of osteoporosis, we also examined the percentage of female patients who had a listed diagnosis of osteoporosis or osteopenia (ICD-9-CM codes 733.00 through 733.09 and 733.90) before and after diagnosis of the distal radial fracture. This method has been used in previous studies to identify Medicare beneficiaries with osteoporosis23,24. In addition, since a 2008 study indicated that only 8% of patients underwent bone mineral density testing following a distal radial fracture25, we searched for claims indicating the performance of bone mineral density testing (CPT codes 77078 through 77083) dated later in the year than the diagnosis of the distal radial fracture.

We examined the prevalence of complications within ninety days after the fracture treatment; these were identified by the presence of relevant ICD-9-CM codes in claims dated within ninety days of the definitive treatment. Complications were classified as either general surgical complications (e.g., complications due to anesthesia or wound infection) or complications specific to a distal radial fracture (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome, malunion, nonunion, or tendon rupture). Complications specific to a distal radial fracture were further classified as either major (requiring surgical treatment) or minor (not requiring surgical treatment) on the basis of the presence or absence of surgical CPT codes in conjunction with the ICD-9-CM code corresponding to the complication. We also used the date of death provided in the Medicare denominator file to calculate the ninety-day mortality rate following treatment of the distal radial fracture.

Since CMS allows each physician to designate up to five self-reported specialties, we used a hierarchy to record physician specialties in order to ensure that we were capturing all relevant specialties and subspecialties. A physician who reported “hand surgery” in any position on the specialty list was classified as a hand surgeon. A physician who reported “orthopaedic surgery” in any position and did not also report “hand surgery” was classified as an orthopaedic surgeon. A physician who did not report either hand surgery or orthopaedic surgery as a surgical specialty was classified as an “other surgeon.” The Outpatient file contains only claims filed by institutional entities (as opposed to individuals), and therefore does not include physician specialty information similar to that found in the Carrier and MedPAR files. Consequently, the specialty of the treating physician could not be determined for 12% of the study cohort because the claims involving the definitive treatment were obtained solely from data in the Outpatient file.

The percentage of patients who received a particular treatment was calculated from the number of patients who received that treatment as the definitive treatment and the total number of patients in the study cohort. Multivariate and multinomial logistic regression was used to determine the association between the odds of receiving internal fixation rather than one of the alternative treatments and patient or surgeon factors. Pinning and external fixation were collapsed into a single treatment category because of the small percentage of patients treated with each of these procedures. Age, sex, race, the presence or absence of comorbidities, socioeconomic status, and diagnosis were used as independent variables; the type of treatment was used as the dependent variable. Binary logistic regression was also performed by combining closed treatment with pinning and external fixation to yield a dependent variable that was dichotomous (i.e., treatment with internal fixation was compared with treatment with a different method). Results are reported as the adjusted odds ratio and the associated 95% confidence interval. Each regression analysis was also repeated on the subgroup of patients treated by a hand surgeon, the subgroup treated by an orthopaedic surgeon who was not a hand surgeon, and the subgroup treated by an “other surgeon” (e.g., a general surgeon or a plastic surgeon) in order to determine the association of physician specialty with receipt of a particular treatment. The “hand surgeon” subspecialty was compared with other orthopaedic surgeons because hand surgeons were expected to be considerably more likely to treat a distal radial fracture with internal fixation.

Hospital referral regions were used to examine regional variations in the data. These regions were defined in The Dartmouth Atlas of Musculoskeletal Health Care by documenting where residents of particular locations received neurosurgical and major cardiovascular surgical treatments. The complete development of hospital referral regions has been well described26. We assumed that each patient was treated in the hospital referral region corresponding to the postal code of his or her residence, an assumption that has been used in previous studies12,15. The percentage of distal radial fractures treated with internal fixation in each hospital referral region was calculated by dividing the number of patients treated with internal fixation in that region by the number of cohort members with an address located within the region. The referral regions were grouped into quintiles on the basis of the percentage of fractures treated with internal fixation, and the results were plotted on a map.

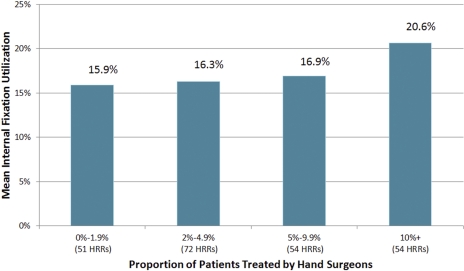

We also calculated the percentage of patients treated by a hand surgeon in each hospital referral region and analyzed the relationship between this percentage and the percentage of fractures treated with internal fixation in the region. The relationship was presented graphically as the percentage of fractures treated with internal fixation in hospital referral regions in which the percentage of patients treated by a hand surgeon was >0% to 1.9%, 2.0% to 4.9%, 5% to 9.9%, and ≥10%. (Hospital referral regions in which no patient in our dataset was treated by a hand surgeon were not included in this analysis.)

Source of Funding

This study was supported by a Clinical Trial Planning Grant (R34 AR055992-01), an Exploratory/Developmental Research Grant Award (R21 AR056988), and a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Results

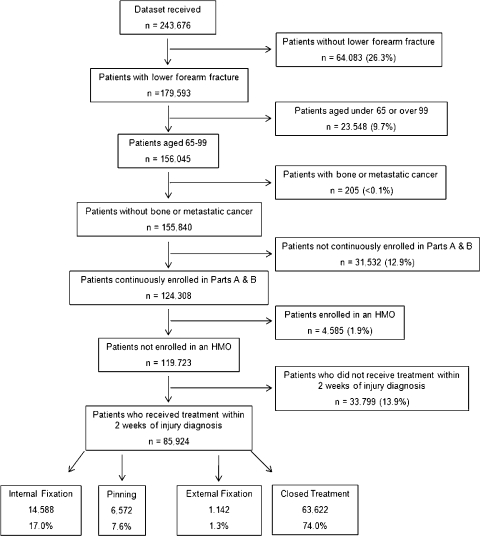

We identified 85,924 Medicare beneficiaries who were diagnosed with and treated for a distal radial fracture in 2007 and who met the remaining criteria for inclusion (Fig. 1). The definitive treatment was internal fixation for 17.0% of these patients. Most patients, 74.0%, were treated with closed reduction and casting; 7.6% were treated with percutaneous pinning (46.3% of these patients received casting or splinting in conjunction with the pinning); and 1.3% were treated with external fixation. Patient demographic information is presented in a table in the Appendix. The internal-fixation group had the highest prevalence of complications specific to distal radial fractures within the first ninety days; nearly 7% of the patients in this group experienced at least one major complication, and 9% experienced at least one minor complication (Table I). The prevalence of individual minor complications specific to distal radial fractures did not differ significantly across the treatment types. Carpal tunnel syndrome was the most common complication specific to distal radial fractures, and occurred in 3.4% of all patients. The prevalence of surgical complications ranged from >13% for both pinning and external fixation to 3% for closed treatment.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing inclusion and exclusion criteria for the cohort of elderly patients with a distal radial fracture. HMO = health maintenance organization.

TABLE I.

Ninety-Day Complication Rate According to Treatment Group

| Internal Fixation (N = 14,588) | Closed Treatment (N = 63,622) | Pinning (N = 6572) | External Fixation (N = 1142) | P Value | |

| Major complications specific to distal radial fracture* | 6.6% | 0.8% | 2.0% | 3.6% | <0.0001 |

| Minor complications specific to distal radial fracture* | 9.1% | 3.9% | 3.6% | 5.0% | <0.0001 |

| General surgical complications | 7.3% | 3.0% | 13.2% | 13.5% | <0.0001 |

| Death | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.6% | <0.0001 |

Complications specific to distal radial fracture = carpal tunnel syndrome, compartment syndrome, complex regional pain syndrome, hypertrophic scar, malunion, nerve injury, nonunion, posttraumatic arthritis, and tendon rupture35. Major complications are those that required surgical intervention; minor complications are those that did not require surgical intervention.

Multivariate logistic regression indicated that men were significantly less likely than women to be treated with internal fixation rather than closed treatment (odds ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76 to 0.85). However, men were significantly more likely than women to be treated with internal fixation rather than pinning or external fixation (odds ratio, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.32). Black patients were significantly less likely that white patients to be treated with internal fixation rather than closed treatment (odds ratio, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.60 to 0.80). The treatment received by patients who were neither white nor black did not differ significantly from the treatment received by white patients (Table II). Univariate logistic regression showed similar results. Men were significantly less likely than women to be treated with internal fixation rather than another treatment (odds ratio, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.80 to 0.89), and black patients were significantly less likely than white patients to be treated with internal fixation rather than another treatment (odds ratio, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.85). Again, the treatment received by patients who were neither white nor black did not differ significantly from the treatment received by white patients.

TABLE II.

Association of Demographic Factors with Odds of Receiving a Particular Treatment

| Odds Ratio of Receiving Internal Fixation (95% CI)* |

|||

| Rather than All Other Treatments | Rather than Closed Treatment | Rather than Pinning or External Fixation | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 0.84 (0.80 to 0.89) | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.85) | 1.20 (1.10 to 1.32) |

| Race | |||

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Black | 0.74 (0.65 to 0.85) | 0.70 (0.60 to 0.80) | 1.19 (0.95 to 1.49) |

| All other races | 0.98 (0.86 to 1.12) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.09) | 1.19 (0.96 to 1.46) |

| Age | |||

| 65-69 yr | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 70-74 yr | 0.86 (0.81 to 0.91) | 0.85 (0.80 to 0.90) | 0.92 (0.84 to 1.00) |

| 75-79 yr | 0.71 (0.67 to 0.75) | 0.69 (0.65 to 0.73) | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.89) |

| 80-84 yr | 0.53 (0.50 to 0.56) | 0.50 (0.48 to 0.54) | 0.71 (0.65 to 0.77) |

| 85-89 yr | 0.34 (0.32 to 0.37) | 0.32 (0.30 to 0.35) | 0.55 (0.50 to 0.61) |

| ≥90 yr | 0.21 (0.19 to 0.24) | 0.19 (0.17 to 0.21) | 0.50 (0.43 to 0.59) |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Medium | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.04) | 1.12 (1.03 to 1.21) |

| High | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.08) | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.01) | 1.60 (1.49 to 1.73) |

Odds ratios were also adjusted for diagnosis and the presence or absence of comorbidities. Bold text indicates a significant association between that demographic characteristic and the odds of receiving internal fixation, when compared with the reference group. CI = confidence interval.

Both multivariate and univariate logistic regression showed that older patients were less likely than the youngest group of patients to be treated with internal fixation rather than closed treatment, rather than pinning or external fixation, and rather than any other treatments. For example, the probability that a patient seventy to seventy-four years old would be treated with internal fixation rather than closed treatment was 15% lower than if the patient was sixty-five to sixty-nine years of age (odds ratio, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.80 to 0.90). The corresponding probability for a patient ninety years of age or older was 81% lower (odds ratio, 0.19; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.21). Patients with a higher socioeconomic status were more likely than patients with the lowest socioeconomic status to be treated with internal fixation rather than pinning or external fixation (Table II).

Patients with comorbid conditions were significantly less likely than patients without comorbid conditions to be treated with internal fixation rather than pinning or external fixation (odds ratio, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.82 to 0.93). Patients diagnosed with fractures of both the radius and the ulna (ICD-9-CM code 813.44) were significantly more likely than patients diagnosed with a Colles fracture (ICD-9-CM code 813.41, the most common diagnosis) to be treated with internal fixation rather than another treatment (odds ratio, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.18) (Table III).

TABLE III.

Association of Patient and Injury Factors with Odds of Receiving a Particular Treatment

| Odds Ratio of Receiving Internal Fixation (95% CI)* |

|||

| Rather than All Other Treatments | Rather than Closed Treatment | Rather than Pinning or External Fixation | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| 813.41: Colles fracture | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 813.40: fracture, lower end of forearm, closed; unspecified | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.10) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.08) | 0.42 (0.11 to 1.57) |

| 813.42: other fracture of distal end of radius (alone), closed | 0.44 (0.42 to 0.46) | 0.40 (0.38 to 0.42) | 1.14 (1.06 to 1.23) |

| 813.44: fracture, radius with ulna, lower end, closed | 1.12 (1.07 to 1.18) | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.21) | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.10) |

| 813.45: torus fracture of radius (alone), closed | 0.50 (0.28 to 0.90) | 0.44 (0.25 to 0.79) | 2.51 (0.71 to 8.81) |

| No. of comorbidities | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥1 | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.03) | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.06) | 0.87 (0.82 to 0.93) |

Odds ratios were also adjusted for diagnosis. Bold text indicates a significant association between that demographic characteristic and the odds of receiving internal fixation, when compared with the reference group. CI = confidence interval.

Only 26.0% of the women in our sample had already been diagnosed with osteoporosis or osteopenia prior to or at the time of the distal radial fracture. However, only an additional 12.6% received bone mineral density testing following diagnosis of the distal radial fracture, despite guidelines recommending testing following such a fracture in this age group27.

Hand surgeons treated 33.7% of the distal radial fractures with internal fixation and 60.4% with closed treatment. Other orthopaedic surgeons, in comparison, treated only 17.6% of the fractures with internal fixation and 71.8% with closed treatment. Nonorthopaedic surgeons performed treatment that was more similar to that of hand surgeons than that of other orthopaedic surgeons; 26.8% of the fractures were treated with internal fixation and 60.8%, with closed treatment. Each of the three specialty groups treated approximately 10% of the fractures with pinning or external fixation.

The 53,855 patients who were treated by surgeons were treated by 12,935 individual surgeons—50,201 (93%) were treated by an orthopaedic surgeon who was not a hand surgeon; 3121 (6%), by a hand surgeon; and 533 (1%), by a surgeon with a different specialty. Multivariate and univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the effect of surgeon specialty on the treatment utilized (Table IV). The results revealed that hand surgeons were significantly more likely than other orthopaedic surgeons to perform internal fixation rather than closed treatment (odds ratio, 2.40; 95% CI, 2.21 to 2.61), rather than pinning or external fixation (odds ratio, 3.22; 95% CI, 2.73 to 3.80), and rather than another treatment (odds ratio, 2.49; 95% CI, 2.29 to 2.70).

TABLE IV.

Association of Specialty of Treating Physician with Odds of Receiving a Particular Treatment

| Odds Ratio of Receiving Internal Fixation (95% CI)* |

|||

| Rather than All Other Treatments | Rather than Closed Treatment | Rather than Pinning or External Fixation | |

| Physician specialty | |||

| Orthopaedic surgery other than hand surgery, n = 50,201 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hand surgery, n = 3121 | 2.49 (2.29 to 2.70) | 2.40 (2.21 to 2.61) | 3.22 (2.73 to 3.80) |

| Other surgery, n = 533† | 1.64 (1.34 to 2.00) | 1.72 (1.40 to 2.12) | 1.27 (0.94 to 1.71) |

Odds ratios were also adjusted for patient sex, race, age, socioeconomic status, and the presence or absence of comorbidities and diagnosis. Bold text indicates a significant association between that demographic characteristic and the odds of receiving internal fixation, when compared with the reference group. CI = confidence interval.

Other surgery = all surgical specialties other than orthopaedic surgery and hand surgery.

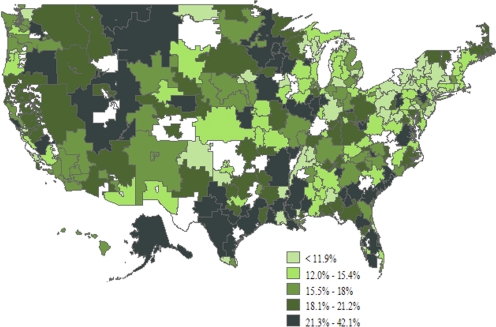

Although the average percentage of distal radial fractures treated with internal fixation was 17.0%, the percentage varied almost tenfold among hospital referral regions, from 4.6% in Paterson, New Jersey, to 42.1% in Rome, Georgia (Fig. 2). Clusters of high use of internal fixation appeared across the country, including in the upper Midwest, the West, southern Texas, and portions of the Southeast. Clusters of low use of internal fixation appeared mainly in the Northeast.

Fig. 2.

United States map showing use of internal fixation for distal radial fractures in the elderly by hospital referral region. (Hospital referral regions indicated in white had too small a population to permit a reliable analysis.)

At least one patient was treated by a hand surgeon in 231 (75.5%) of the 306 hospital referral regions. The hand surgeons in these regions treated an average of 26.8% of the distal radial fractures with internal fixation (range, 0% to 85.7%). Use of internal fixation was positively correlated with the percentage of patients in the referral region who were treated by a hand surgeon (correlation coefficient, 0.34; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mean use of internal fixation according to the percentage of patients in the hospital referral region (HRR) who were treated by a hand surgeon.

Discussion

Our analysis revealed that 17.0% of distal radial fractures in the Medicare population were treated with internal fixation in 2007. A previous study had indicated that this percentage grew from 3.3% in 1996 to 15.8% in 20051, and our current study indicated that the use of internal fixation has continued to increase. However, despite this overall increase in the use of internal fixation, particular patient populations—male and black patients—were less likely than other populations to be treated with internal fixation. We hypothesized that men may be less likely to be treated with internal fixation because they are much less likely to have osteoporosis16, the main risk factor for collapse of the fracture following closed treatment. A surgeon may be reluctant to pursue a more invasive treatment if he or she expects the patient to experience a satisfactory outcome following a less invasive treatment. Likewise, black patients may be less likely to be treated with internal fixation because of their lower risk of osteoporosis17,18.

Patient age and the presence of comorbid conditions also correlated significantly with the use of internal fixation. Older patients were less likely to receive internal fixation, which is not surprising since functional demands decrease with age and the surgical risk increases with age. Likewise, the elevated surgical risk in patients with comorbid conditions may also explain why these patients were less likely than patients without such conditions to be treated with internal fixation. Finally, the diagnosis was significantly correlated with the use of internal fixation rather than another treatment. A patient diagnosed with both a distal radial fracture and a distal ulnar fracture was more likely than a patient with only a distal radial fracture to be treated with internal fixation. This greater use of internal fixation may reflect the surgeon's attempt to address the instability of the forearm axis that can result from this fracture pattern.

It is not surprising that more than one-quarter of the women in our cohort were diagnosed with osteoporosis or osteopenia. However, only an additional 13% of the women received bone mineral density testing following the fracture. This percentage is higher that the percentage reported in a previous study25, but it is still rather low. We were unable to determine whether the low rate resulted because patients were not referred for testing or because they were referred but declined to undergo the test.

Hand surgeons are currently utilizing the new internal fixation technology at a higher rate than other orthopaedic surgeons are, even after controlling for patient factors such as sex, age, race, and the presence of comorbidities. There are two possible explanations for this finding. First, hand surgeons may be more aware of this new technology. Second, a patient with a more severe fracture, which would be more amenable to stabilization with an internal fixation technique, may be more likely to be referred to a hand surgeon who has expertise with this technique.

Large regional variations in the use of internal fixation were observed, with clusters of higher and lower use across the country. However, the information available to us did not allow us to discern the exact cause of these regional variations. The occurrence of regional variations in the treatment of distal radial fractures in the elderly is not surprising, given the lack of consensus regarding the optimal treatment of such fractures in this age group.

As with any study utilizing the Medicare database, we relied on the accuracy of the data provided. We performed several checks of face validity by noting results that seemed intuitive, such as the fact that our dataset contained many more women than men and the fact that emergency medicine and primary care physicians utilized closed reduction far more often than they utilized other treatment methods. Studies of the accuracy of Medicare claims for a variety of conditions, both surgical and medical, have indicated a positive predictive value of between 86% and 99%28-31. A further limitation of our study was the limited nature of the patient data, which represented only basic demographic information. We did not have access to clinical information (such as radiographic findings) indicating injury severity, which plays an important role in treatment decisions. Finally, we were able to track osteoporosis diagnosis and bone mineral density testing only through the 2007 calendar year. Our analysis of these factors may therefore have missed patients who sustained a distal radial fracture late in 2007 and underwent bone mineral density testing in 2008.

Our analysis revealed that the use of internal fixation was not uniform throughout the country or across segments of the population. These variations appear to have resulted from both patient factors (as would be expected) and provider factors—specifically, whether the surgeon was a hand specialist. The wide regional variations in the use of internal fixation emphasize the lack of evidence-based information regarding the optimal treatment of this common injury. This lack of comparative-effectiveness evidence is detrimental to both patients and providers32-34. In the absence of clear guidelines, payers such as Medicare may be inclined to steer patients toward less expensive, and potentially less effective, treatments because there is no solid evidence that the more expensive treatment is superior. Providers in a specialty (in this case, hand surgery) that frequently adopts the use of new technologies earlier than nonspecialists do may be criticized for selecting an expensive treatment when comparative-outcome data are not yet available.

There is no indication that use of internal fixation for the treatment of distal radial fractures is declining. Since the nation's health care system is expected to incur even greater costs in the future to treat these fractures in the Medicare population, a randomized, multicenter clinical trial is greatly needed to determine whether or not internal fixation is truly the optimal treatment in this population.

Supplementary Material

A table summarizing patient demographic data, diagnoses, and treatments

Footnotes

Disclosure: One or more of the authors received payments or services, either directly or indirectly (i.e., via his or her institution), from a third party in support of an aspect of this work. In addition, one or more of the authors, or his or her institution, has had a financial relationship, in the thirty-six months prior to submission of this work, with an entity in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. No author has had any other relationships, or has engaged in any other activities, that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. The complete Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest submitted by authors are always provided with the online version of the article.

References

- 1.Chung KC, Shauver MJ, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in the United States in the treatment of distal radial fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1868-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohsfeldt RL, Borisov NN, Sheer RL. Fragility fracture-related direct medical costs in the first year following a nonvertebral fracture in a managed care setting. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:252-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray NF, Chan JK, Thamer M, Melton LJ., 3rd Medical expenditures for the treatment of osteoporotic fractures in the United States in 1995: report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:24-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Census Bureau Projected population of the United States, by age and sex: 2000-2050. http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usinterimproj/natprojtab02a.pdf. Accessed 2010 Apr 5

- 5.Mackenney PJ, McQueen MM, Elton R. Prediction of instability in distal radial fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1944-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strange-Vognsen HH. Intraarticular fractures of the distal end of the radius in young adults. A 16 (2-26) year follow-up of 42 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1991;62:527-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung KC, Squitieri L, Kim HM. Comparative outcomes study using the volar locking plating system for distal radius fractures in both young adults and adults older than 60 years. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:809-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orbay JL, Fernandez DL. Volar fixation for dorsally displaced fractures of the distal radius: a preliminary report. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27:205-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orbay JL, Fernandez DL. Volar fixed-angle plate fixation for unstable distal radius fractures in the elderly patient. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29:96-102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drobetz H, Kutscha-Lissberg E. Osteosynthesis of distal radial fractures with a volar locking screw plate system. Int Orthop. 2003;27:1-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glickel SZ, Catalano LW, Raia FJ, Barron OA, Grabow R, Chia B. Long-term outcomes of closed reduction and percutaneous pinning for the treatment of distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:1700-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fanuele J, Koval KJ, Lurie J, Zhou W, Tosteson A, Ring D. Distal radial fracture treatment: what you get may depend on your age and address. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1313-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Geographic variation in epidural steroid injection use in Medicare patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1730-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson PR, Bronner KK, Fisher ES. United States’ trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992-2003. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2707-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koval KJ, Lurie J, Zhou W, Sparks MB, Cantu RV, Sporer SM, Weinstein J. Ankle fractures in the elderly: what you get depends on where you live and who you see. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:635-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singer BR, McLauchlan GJ, Robinson CM, Christie J. Epidemiology of fractures in 15,000 adults: the influence of age and gender. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:243-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung KC, Spilson SV. The frequency and epidemiology of hand and forearm fractures in the United States. J Hand Surg Am. 2001;26:908-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas E, Wilkie R, Peat G, Hill S, Dziedzic K, Croft P. The North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project–NorStOP: prospective, 3-year study of the epidemiology and management of clinical osteoarthritis in a general population of older adults. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Social Security Administration Medicare. http://www.ssa.gov/pubs/10043.pdf. Accessed 2010 Apr 5

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, Chambless L, Massing M, Nieto FJ, Sorlie P, Szklo M, Tyroler HA, Watson RL. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:99-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birkmeyer NJ, Gu N, Baser O, Morris AM, Birkmeyer JD. Socioeconomic status and surgical mortality in the elderly. Med Care. 2008;46:893-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng H, Gary LC, Curtis JR, Saag KG, Kilgore ML, Morrisey MA, Matthews R, Smith W, Yun H, Delzell E. Estimated prevalence and patterns of presumed osteoporosis among older Americans based on Medicare data. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1507-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pike C, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, Sharma H, Burge R, Edgell ET. Direct and indirect costs of non-vertebral fracture patients with osteoporosis in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28:395-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rozental TD, Makhni EC, Day CS, Bouxsein ML. Improving evaluation and treatment for osteoporosis following distal radial fractures. A prospective randomized intervention. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:953-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinstein JN, Birkmeyer JD, The Dartmouth atlas of musculoskeletal health care. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing; 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim LS, Hoeksema LJ, Sherin K; ACPM Prevention Practice Committee. Screening for osteoporosis in the adult U.S population: ACPM position statement on preventive practice. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:366-75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du X, Freeman JL, Warren JL, Nattinger AB, Zhang D, Goodwin JS. Accuracy and completeness of Medicare claims data for surgical treatment of breast cancer. Med Care. 2000;38:719-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Losina E, Barrett J, Baron JA, Katz JN. Accuracy of Medicare claims data for rheumatologic diagnoses in total hip replacement recipients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:515-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noyes K, Liu H, Holloway R, Dick AW. Accuracy of Medicare claims data in identifying Parkinsonism cases: comparison with the Medicare current beneficiary survey. Mov Disord. 2007;22:509-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiyota Y, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Cannuscio CC, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Accuracy of Medicare claims-based diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction: estimating positive predictive value on the basis of review of hospital records. Am Heart J. 2004;148:99-104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung KC, Ram AN. Evidence-based medicine: the fourth revolution in American medicine? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:389-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swanson JA, Schmitz D, Chung KC. How to practice evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:286-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung KC, Swanson JA, Schmitz D, Sullivan D, Rohrich RJ. Introducing evidence-based medicine to plastic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1385-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diaz-Garcia RJ, Oda T, Shauver MJ, Chung KC. A systematic review of outcomes and complications of treating unstable distal radial fractures in the elderly. J Hand Surg. 2011;36:824-835e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A table summarizing patient demographic data, diagnoses, and treatments