INTRODUCTION

The reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection may occur during the course of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection as an initial indicator of the disease. Post-herpetic neuralgia and multiple vesiculobullous lesions have been described in HIV-infected patients with herpes zoster.1,2 Nonadherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has a significant impact on the patient's quality of life and increases the risk of mortality.3 We report a case of an HIV-infected patient who developed herpes zoster due to nonadherence to HAART.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 55-year-old female patient of afro-descendant was diagnosed with AIDS in 1999, when she developed chronic diarrhea and weight loss. This patient was a homemaker born in Bahia and residing in Serra-ES (Brazil) with an HIV-positive and nonexclusive sexual partner and three children. She had been in menopause for six years at the time of VZV diagnosis. Antiretroviral treatment was initiated with zidovudine (AZT) + didanosine in 2001 because her CD4+ count fell below 350 cells/mm3. Because of noncompliance, she remained without anti-retroviral medication for 31 months, which, in 2008, allowed her to be susceptible to a very aggressive clinical episode of herpes zoster with severe neuralgia, which led to a seven-day hospitalization. Initially, she presented with maculopapular lesions that progressed into vesicles and then pustules and crusts on the right thoracic region following the nerve path (Figure 1 and Figure 2) that lasted for 12 days. Laboratory tests showed a normal complete blood count (CBC), a viral load (VL) of 27,500 copies/mL and a CD4+ T lymphocyte count of 328 cells/mm3.

Figure 1.

Grouped erythematous vesiculous and crusted herpes zoster lesions on the right thoracic region along the intercostal nerve path.

Figure 2.

Grouped erythematous vesiculous and crusted herpes zoster lesions on the right thoracic region along the intercostal nerve path – back view.

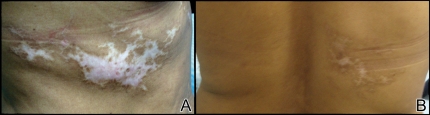

The patient was treated with intravenous acyclovir for seven days, with marked improvement of the lesions. She started therapy with AZT + lamivudine + abacavir. At the same time, the cervical oncotic cytology was suggestive of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia I (CIN I) and infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). Colposcopy suggested CIN I, and the cytological samples from the cervix after 3, 6, 12, and 18 months were normal. A hypochromic scar remained in the affected area after the herpes zoster was treated (Figures 3A and B), which caused constraints on the patient's social life and affected her quality of life. Moreover, she suffered from persistent post-herpetic neuritis that lasted for 12 months. The patient remains in a clinical follow-up program in the infectious and parasitic diseases sector at a public hospital in Espírito Santo state. Currently, the patient adheres correctly to the antiretroviral therapy and has had no relapses of herpes zoster, and her quality of life has improved significantly.

Figure 3.

A) Hypochromic scars after herpes zoster on the thoracic region along the intercostal nerve path. B) Hypochromic scars after herpes zoster on the thoracic region along the intercostal nerve path – back view.

Above, we described an aggressive form of infection caused by VZV that served as a warning flag for AIDS in a patient who did not adhere to HAART.

The next section describes the factors involved in noncompliance and provides support for a more effective approach to the clinical follow-up of individuals with HIV.

DISCUSSION

Patients who meet the definition of AIDS, such as the patient described in this report, exhibit significant inhibition of the immune system and are susceptible to new bacterial, fungal, and viral infections and to the reactivation of prior infections. Some of these infections are considered AIDS defining and can be categorized as opportunistic infections (OI).4

Some viral agents, especially herpesviruses, can cause acute and persistent lytic infections, signaling immunosuppression in an early symptomatic phase of AIDS. Among these, VZV stands out as one viral agent that can be reactivated by the HIV-positive patient's immunological changes,5 manifesting clinically as vesicles that break down into ulcers following the nerve path and as pre- and post-injury neuralgia associated with intense pain. All of these events, associated with the immunosuppression, occurred were experienced by the patient described in this report.

The current literature indicates that noncompliance is the largest cause of failure of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). HAART must be understood as an action in which the patient not only follows medical advice but also understands and agrees to follow the guidelines and requirements. Adherence to HAART includes following schedules, maintaining proper dosage with no interruptions (regardless of social life or travels) and even making use of a balanced diet to support the therapy. Adverse effects or fear of exposure may influence the patient's motivation for not adhering to the therapy, thereby jeopardizing the efficacy of the recommended treatment and potentially impairing the quality of life (Ferreira et al., 2011).6

Studies have identified different factors as causes of patient noncompliance with antiretroviral treatment, including fear of side effects, lack of adequate food, difficulty integrating the treatment routine into their lives, forgetting when to take the medicine, the influence of other people in their social life, the amount of medicine to take and the emotional state (Kaishusha Mupendwa et al., 2009).7

Other factors associated with noncompliance include age, education, injecting drug use, alcohol use, drug regimens with protease inhibitors, the presence of clinical signs and symptoms, loss of companions, time of diagnosis of HIV infection, a break in the continuity of care by one doctor or hospital and depression (Glass et al., 2010).8 Two of these issues are particularly notable: the “emotional state” and depression. The patient in this report was depressed and exhibited an altered emotional state, which were considered possible causes for her refusal to use the proposed antiretroviral therapy. The patient, at present, is on HAART therapy and antidepressants in outpatient care.

Adherence measures are currently being reassessed because of flaws in their evaluation standards (Zijenah, 2006; Bangsberg 2002).9,10 The search for a better quality of life for HIV-infected individuals should be the central aim when following this clinical group. This goal includes good doctor-patient communication, respect for the specifics of the infection and the life dynamics of each individual, support from a multidisciplinary team, and a continual, active search for these patients, if necessary, to increase adherence.

In conclusion, increasing adherence to HAART plays an important role in reducing opportunistic infections, such as VZV, and in improving the patient's life by reducing mortality.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arvin A. Aging, immunity, and the varicella-zoster virus. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2266–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058091. 10.1056/NEJMp058091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson RW. Zoster-associated pain: what is known, who is at risk and how can it be managed. Herpes. 2007;14((Suppl 2)):30A–34A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abaasa AM, Todd J, Ekoru K, Kalyango JN, Levin J, Odeke E, et al. Good adherence to HAART and improved survival in a community HIV/AIDS treatment and care programme: the experience of The AIDS Support Organization (TASO), Kampala, Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:241. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-241. 10.1186/1472-6963-8-241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirk O, Reiss P, Uberti-Foppa C, Bickel M, Gerstoft J, Pradier C, et al. Safe interruption of maintenance therapy against previous infection with four common HIV-associated opportunistic pathogens during potent antiretroviral therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:239–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-4-200208200-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gebo KAMD, Kalyani R, Moore RD, Polydefkis MJ. The Incidence of, Risk Factors for, and Sequelae of Herpes Zoster Among HIV Patients in the Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Era. J AIDS. 2005;40:169–74. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000178408.62675.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira DC, Passos MRL, Rubini NPM, Knupp RRS, Curvelo JAR, Reis HLB. Validation study of a scale of life quality evaluation in a group of pediatric patients infected by HIV. Cien Saude Colet. 2011;16:2643–52. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232011000500034. 10.1590/S1413-81232011000500034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaishusha MupendwaBP, Kadima NtokamundaJL. Treatment adhesion and factors affecting it at the Kadutu Clinic (Democratic Republic of the Congo) Sante. 2009;19:205–15. doi: 10.1684/san.2009.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass TR, Battegay M, Cavassini M, De Geest S, Furrer H, Vernazza PL, et al. Longitudinal analysis of patterns and predictors of changes in self-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy: Swiss HIV Cohort Study. J AIDS. 2010;54:197–203. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ca48bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zijenah LS, Kadzirange G, Tobaiwa O, Rusakaniko S, Gwanzura C, Kufa T, et al. Immunologic and virologic efficacy of generic nevirapine, zidovudine and lamivudine in the treatment of HIV-1 infected women with pre-exposure to single dose Nevirapine or short course zidovudine, in Zimbabwe. 2006 Thirteenth Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Denver. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bangsberg DR, Deeks SG. Is average adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy enough. JGen Intern Med. 2002;17:812–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.20812.x. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.20812.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]