Abstract

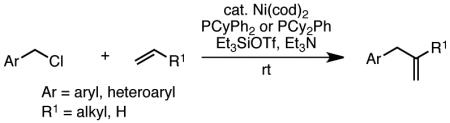

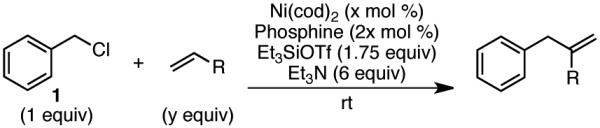

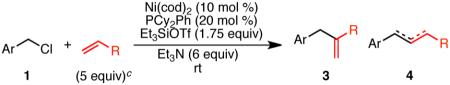

Nickel-catalyzed intermolecular benzylation and heterobenzylation of unactivated alkenes to provide functionalized allylbenzene derivatives is described. A wide range of both the benzyl chloride and alkene coupling partners are tolerated. In contrast to analogous palladium-catalyzed variants of this process, all reactions described herein employ electronically unbiased aliphatic olefins (including ethylene), proceed at room temperature and provide 1,1-disubstituted olefins over the more commonly observed 1,2-disubstituted olefins with very high selectivity.

The Heck-Mizoroki reaction1 is a powerful carbon-carbon bond-forming process that couples alkenes with a wide scope of aryl, alkenyl, and alkyl halides.2 When benzyl3 chlorides are employed, the coupling provides useful allylbenzene derivatives, a versatile functional group in organic synthesis. Despite the fact that the first coupling of methyl acrylate using benzyl chloride was described by Heck nearly 40 years ago,4 the intervening years have witnessed only sporadic reports of couplings with benzyl halides or related derivatives.5,6 Of these, the chief limitation is substrate scope; most examples utilize olefins bearing substituents that facilitate coupling electronically, such as acrylates, styrenes and N-vinyl amides. The benzylation of widely available aliphatic olefin feedstocks7 has not yet been realized. Moreover, the products obtained in these reactions are subject to olefin isomerization, and the previously reported examples generally afford a mixture of allylbenzene derivatives (kinetic products) and isomeric styrenes. This problem can be difficult to control at the high reaction temperatures (100-130 ° C) employed. A further unsolved problem is regioselectivity; to the best of our knowledge no examples of Heck-type olefin couplings of simple alkenes that give 1,1-disubstituted products have been reported.8 While the ruthenium-catalyzed ene-yne coupling developed by Trost is a notable example,9 there are far fewer methods for the direct assembly of 1,1-disubstituted olefins compared to 1,2-disubstituted olefins, despite the fact that 1,1-disubstituted olefins are prevalent in many biologically active compounds10 and are very useful intermediates in target-oriented syntheses.11

|

(1) |

We address herein several of the aforementioned deficiencies. The nickel-catalyzed intermolecular benzylation of simple, unactivated olefins (eq 1) represents the first example of an alkene benzylation method that (a) utilizes α-olefins as substrates, including ethylene and propylene, (b) displays high selectivity for 1,1-disubstituted olefins, (c) avoids isomerization of the desired allylbenzene derivatives to the styrenyl products, and finally, (d) proceeds smoothly at room temperature.

We initially examined the nickel-catalyzed coupling reaction of ethylene (1 atm) and benzyl alcohol (1 equiv) in the presence of Et3SiOTf (1.75 equiv) and triethylamine (6 equiv).12 In stark contrast to our previously reported nickel-catalyzed olefin allylation,12d methyl ether and methyl carbonate derivatives exhibited no conversion, indicating that they failed to undergo oxidative addition.13 Benzyl bromide afforded the product in poor yield and underwent undesired side reactions with the triethylamine.14 Ultimately, benzyl chloride (1) proved to be a suitable substrate.

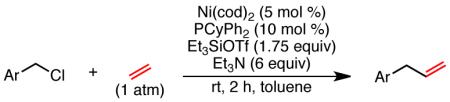

For these initial studies with ethylene, PCyPh2 provided superior reactivity and yields (entries 1 and 2). Only 1 mol % of the nickel complex derived from Ni(cod)2 and PCyPh2 is required to catalyze the reaction, affording the product in quantitative yield. Using 5 mol % of the catalyst drastically increases the reaction rate, reducing the time required for complete conversion from 16 h to 2 h (entry 3). Decreasing the catalyst loading beyond 1 mol % significantly lowers the conversion (entry 4). No reaction took place with the exclusion of Ni(cod)2 and only a trace amount of the product was formed without addition of Et3SiOTf (entry 5). In the latter case the consumption of benzyl chloride is believed to be caused by a change in mechanism from the desired manifold (vide infra) to one which favors homocoupling.

A particularly noteworthy feature of this method is the regioselectivity observed when 1-alkyl-substituted (R ≠ H) alkenes are used. Excellent regioselectivity in favor of the unusual 1,1-over 1,2-disubstituted olefins (the exclusive regioisomer observed in all previously reported cases) is obtained under these nickel-catalyzed conditions. Furthermore, styrene and acrylate (excellent substrates in other Heck-type analogues) are poor substrates in this catalytic system, rendering this methodology complementary in both regioselectivity and reactivity to its palladium analogues. In contrast to ethylene, for the α-olefins, higher conversion (100%) was obtained with PCy2Ph compared to PCyPh2 (59% conversion, entries 6 and 7). A catalyst loading of 5 mol % was sufficient to catalyze the reaction, but improved yields were obtained when the loading was increased to 10 mol % (entries 7 and 8). The reactions with 1-octene proceeded readily at ambient temperature, albeit at a slower rate that was observed for ethylene. For 1-octene, 2 equivalents of olefin were required for complete conversion(entry 9), but with a slightly diminished yield compared to the reaction in which 5 equivalents were used (entry 7).

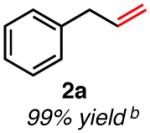

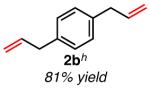

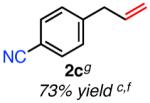

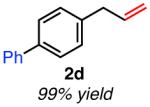

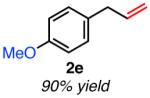

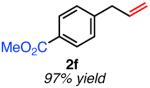

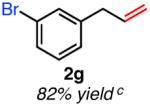

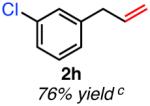

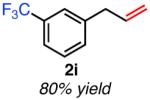

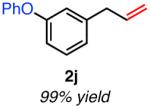

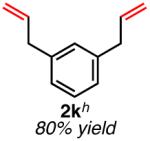

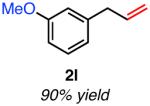

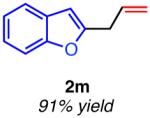

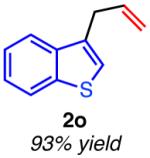

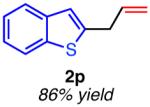

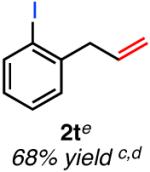

Given the rapid rate with which the coupling of ethylene proceeded, we used this simple olefin to examine the scope of the reaction with regard to the benzyl chloride partner. Gratifyingly, good to excellent yields were observed across a broad range of substrates under these optimized conditions (Table 2).15 Various benzyl chloride derivatives were tolerated, including those with para-(2a-f), meta-(2g-l), hetero-(2m-r) and ortho-substitution (2s-t). Both electron-rich and electron-deficient benzyl chlorides were coupled within 2 h at room temperature. High yields were also observed when halogen-substituted aromatic substrates were used. Even an ortho-iodo benzyl chloride was successfully employed, to afford the desired product (2t) in good yield. In this case, only 4% of the product derived from oxidative addition into the carbon-iodide bond was concomitantly formed. Cyano (2c) and ester (2f) functional groups on the aromatic rings were also tolerated, and α,α’-dichloroxylenes (meta and para) were efficient substrates for the preparation of diallylbenzenes (2b and 2k). It is noteworthy that nitrogen-protecting groups, Boc and Ts (2n, 2q and 2r), located β to the benzylic carbon, did not interfere with the reaction.

Table 2. Nickel-Catalyzed Benzylation of Ethylenea.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| para-substituted | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| meta-substituted | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| hetero-substituted | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ortho-substituted | ||

|

|

|

Isolated yield unless otherwise noted.

Determined by GC (internal standard).

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy (internal standard).

Yield obtained with 10 mol % catalyst.

2,3-Dihydro-1H-indene (4%) observed as inseparable byproduct.

Yield obtained with 20 mol % catalyst loading.

4-Cyano-β-methylstyrene (5%) obtained as an inseparable byproduct.

Obtained with 2.5 equiv Et3SiOTf.

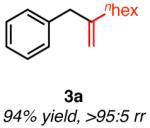

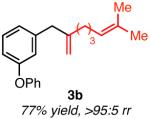

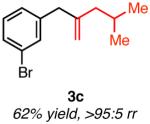

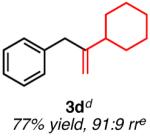

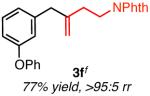

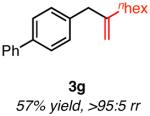

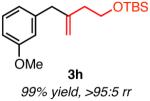

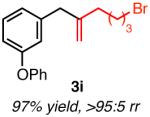

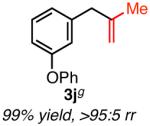

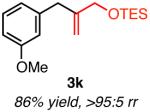

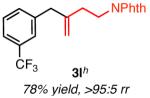

Having examined the substrate scope of functional groups on the benzyl chloride with ethylene, we next turned our attention to the substituted olefins. A variety of functionality on the α-olefin is tolerated, including silyl ethers (3h and 3k), phthalimides (3f and 3l) and alkyl groups with α-branching (3d). An alkene containing a pendant alkyl bromide underwent the coupling with no observable side reactions, furnishing 3i in 97% yield and thereby demonstrating the excellent chemoselectivity of this reaction. Propylene, a gaseous olefin, afforded the desired product (3j) in excellent yield. Notably, α-olefins containing pendant olefins (3b) are also tolerated. As was observed for ethylene, aryl bromides are compatible with the reaction conditions (3c). A trifluoromethyl substituent was also tolerated under the reaction conditions. Despite the presence of three fluorine atoms at a benzylic position, no evidence of fluoride substitution was detected (entry 3l).16

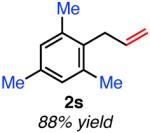

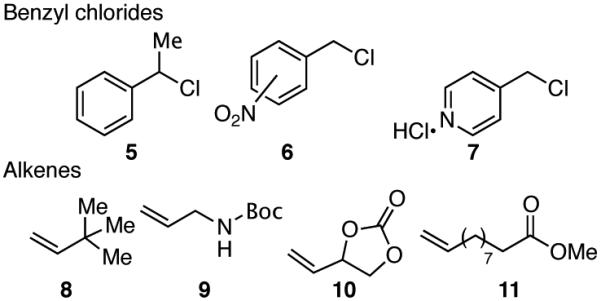

Attempts to employ more highly substituted benzyl chlorides revealed the limits of this reaction (Figure 1). No reaction was observed upon exposure of 5, containing a methyl substituent at the benzylic position, to the reaction. Further examination of scope revealed that nitro-substituted aromatic groups were not compatible, despite the compatibility of nitrile- and ester-substituted benzyl chlorides. No conversion was observed when a pyridine was present (7) as the hetero-substituent, further revealing the limits of this catalyst system. We also examined the functional group tolerance with regard to the alkene partner. The steric limit is reached with tert-butyl ethylene 8, for which no reaction was observed. While no reaction was observed for carbamate 9, carbonate 10 formed an intractable mixture of products. To probe the compatibility of substrates containing enolizable protons, ester 11 was examined; the ester failed to undergo complete conversion even when more than 2 equivalents of Et3SiOTf were used.

Figure 1.

Substrates that did not undergo the desired benzylation.

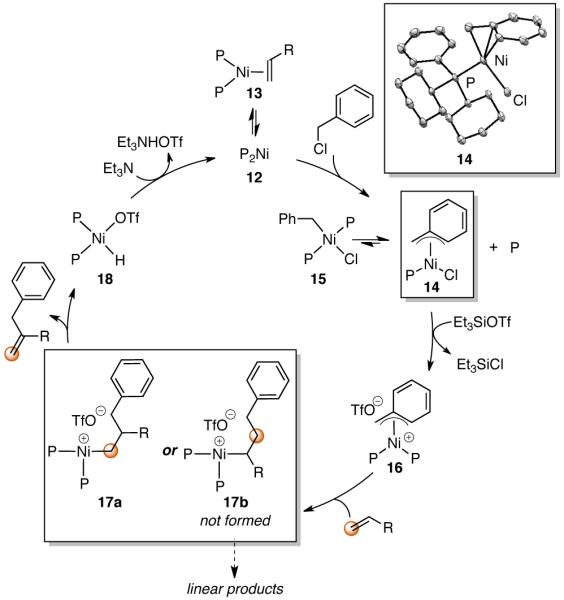

We propose the reaction mechanism shown in Scheme 1. Nickel(0) complex 12, possibly in equilibrium with alkene (substrate or cyclooctadiene) complex 13, adds oxidatively to benzyl chloride without mediation of Et3SiOTf, affording a mixture of nickel(II) complex 14, bearing an η3-benzyl ligand and one phosphine, and 15 bearing an η 1-benzyl ligand and two phosphines.17 In solution at room temperature, a rapid equilibrium exists between complexes 14 and 15, but favors complex 14.18 As depicted, Ni(η3-CH2C6H5)(PCy2Ph)Cl (14) has been characterized by X-ray crystallography. Counteranion exchange from Cl− to TfO− mediated by Et3SiOTf provides cationic nickel complex 16,19 which then undergoes olefin coordination. Subsequent migratory insertion, the carbon-carbon bond-forming step in which the regioselectivity is determined, gives alkyl-nickel species 17. This is followed by β-hydride elimination, affording the 1,1-disubstituted olefin product and nickel complex 18. Nickel(0) complex 12 is then regenerated by triethylamine, completing the catalytic cycle.

Scheme 1. Proposed Catalytic Cycle and ORTEP Drawing of η3-Nickel Complex 14a.

a P= PR3.

In Heck reactions catalyzed by palladium, the selectivity of the olefin insertion step is governed by a combination of electrostatic and frontier orbital effects, yet which effect is dominant in this reaction is unclear at this time. In the proposed mechanism, the productive pathway is the one that places the metal on the less substituted olefinic carbon. Given the relatively shorter nickel-carbon bond lengths (compared to the analogous palladium system), it is conceivable that steric effects are the dominant factor in this reaction. The ease with which ethylene undergoes the reaction compared to substituted olefins (2 h versus 16 h), despite its significantly lower relative concentration (1 atm in 0.2M toluene versus neat in 5 equiv olefin), lends support to this argument. However, the most sterically demanding olefin tolerated by the reaction—vinyl cyclohexane—was also the only substrate that afforded any of the linear adduct.

The observation that 36% of the benzyl chloride is converted to the homo dimer in the absence of Et3SiOTf (Table 1, entry 5) can also be rationalized using this mechanism. Unable to form allyl complex 16, it is likely that two molecules of the nickel chloride (14, 15) undergo disproportionation to the catalytically incompetent Ni(II)Cl2 and a Ni(II)Bn2 intermediate. The latter would then afford the self-coupled product (dihydrostilbene) via reductive elimination.

Table 1. Optimization of Olefin Benzylation Conditions.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | PR3 | y | x | time (h) |

conv (%)a |

yield (%)a |

| 1 | H | P(o-anis)3 | 1 atm | 20 | 23 | 76 | 73 |

| 2 | H | PCyPh2 | 1 atm | 1 | 13 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | H | PCyPh2 | 1 atm | 5 | 2 | 100 | 100 |

| 4 | H | PCyPh2 | 1 atm | 0.5 | 16 | 17 | 17 |

| 5b | H | PCyPh2 | 1 atm | 20 | 2 | 36 | 1 |

| 6 | n-hex | PCyPh2 | 5 | 10 | 16 | 59 | 28 |

| 7 | n-hex | PCy2Ph | 5 | 10 | 16 | 100 | 90 |

| 8 | n-hex | PCy2Ph | 5 | 5 | 16 | 100 | 80 |

| 9 | n-hex | PCy2Ph | 2 | 10 | 16 | 100 | 78 |

| 10 | n-hex | PCy2Ph | 1 | 10 | 16 | 86 | 54 |

Determined by GC.

Et3SiOTf not used.

In conclusion, we have described a novel nickel-catalyzed intermolecular benzylation of simple, widely available α -olefins and ethylene. The functional group tolerance seen across the broad range of substrates studied rivals that observed for analogous reported palladiumcatalyzed methods. The observed selectivity favoring 1,1-versus 1,2-disubstituted olefins is a unique and significant feature of this methodology. Additionally, the relatively low temperature at which these reactions proceed (room temperature) is unique. The above study represents an important advance in catalytic reactions using simple olefins as substrates. We are currently investigating Et3SiOTf-free processes as well as other types of catalytic reactions using simple olefins as nucleophiles in carbon-carbon bond-forming reactions.

Supplementary Material

Table 3. Nickel-Catalyzed Benzylation of 1-Substituted Olefinsa,b.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All yields are isolated yields.

rr = Regioisomeric ratio (3/4).

Reactions carried out neat in olefin (5 equiv) except for the examples that employ a gaseous or solid olefin; for these entries, toluene was used as a solvent.

20 mol % of the catalyst.

Total yield of 3 and 4.

Toluene (1.4 M) used as solvent; 1.5 equiv of olefin.

Propylene introduced via balloon (1 atm); toluene (0.2 M) used as solvent.

Toluene (1.2 M) used as solvent.

Acknowledgment

Support for this work was provided by the NIGMS (GM 72566 and GM 63755). We are grateful to Dr. Peter Müller (MIT) and Dr. Michael Takase (MIT) for X-ray diffraction analysis. R. M. thanks JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad for financial support and Dr. Akemi Moriyama (Children’s Hospital Boston, deceased March 2011) for encouragement support. A.C.G. thanks NIH for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, spectral data for all unknown compounds and CIF file for complex 14. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Heck RF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:5518. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mizoroki T, Mori K, Ozaki A. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1971;44:581. [Google Scholar]

- (2).For reviews on the Heck-Mizoroki reaction, see: Bräse S, de Meijere A. In: Metal-catalyzed Cross-coupling Reactions. Diederich F, Stang PJ, editors. Weinheim; Wiley-VCH: 1998. Chapter 3. Link JT, Overman LE. In: Metal-catalyzed Cross-coupling Reactions. Diederich F, Stang PJ, editors. Weinheim; Wiley-VCH: 1998. Chapter 6. Brseä S, de Meijere A. In: Metal-catalyzed Cross-coupling Reactions. 2nd ed. de Meijere A, Diederich F, editors. Weinheim; Wiley-VCH: 2004. Chapter 5. Beletskaya IP, Cheprakov AV. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:3009. doi: 10.1021/cr9903048. Dounay AB, Overman LE. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2945–2963. doi: 10.1021/cr020039h. Oes-treich M. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2007;24:169–192. Shibasaki M, Ohshima T, Itano W. Science of Synthesis. 2011;3:483–512. Le Bras J, Muzart J. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1170–1214. doi: 10.1021/cr100209d.

- (3).In the context of this publication, “benzylation” refers to reaction at the carbon attached to an aromatic ring.

- (4).Heck RF, Nolley JP., Jr. J. Org. Chem. 1972;37:2320. [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Wu G.-z., Lamaty F, Negishi E.-i. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:2507. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yi P, Zhuangyu Z, Hongwen H. Synth. Commun. 1992;22:2019. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yi P, Zhuangyu Z, Hongwen H. Synthesis. 1995;245 [Google Scholar]; (d) Kumar P. Org. Prep. Proc. Int. 1997;29:477. [Google Scholar]; (e) Wang L, Pan Y, Jiang X, Hu H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:725. [Google Scholar]; (f) Narahashi H, Yamamoto A, Shimizu I. Chem. Lett. 2004;33:348. [Google Scholar]; (g) Narahashi H, Shimizu I, Yamamoto A. J. Organomet. Chem. 2008;693:283. [Google Scholar]

- (6).To the best of our knowledge, there is only one example of intermo-lecular benzylation of a simple olefin, where a styrene-type product derived from olefin isomerization of the initially formed product was obtained. See ref 5a.

- (7).Lappin GR, Sauer JD, editors. Alpha Olefins Applications Handbook. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1989. Alpha olefins are regarded as a chemical feedstock. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cross-coupling reactions of benzyl halides (or their derivatives) and alkenyl organometallics have been reported, although very few methods to synthesize 1,1-disubstituted olefins were reported. For selected examples, see: Milstein D, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:4992. Kamlage S, Sefkow M, Peter MG. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:2938. doi: 10.1021/jo981840n. Zhang S, Marshall D, Liebeskind LS. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:2796. doi: 10.1021/jo982250s. Pérez I, Sestelo JP, Sarandeses LA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:4155. doi: 10.1021/ja004195m. See also ref 10a and 11.

- (9).For initial reports describing branch selectivity in the ruthenium-catalyzed intermolecular ene-yne coupling, see: Trost BM, Toste FD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:7739–7743. Trost BM, Machacek M, Schnaderbeck MJ. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1761–1764. doi: 10.1021/ol0059504. Trost BM, Pinkerton AB, Toste FD, Sperrle M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12504–12509. doi: 10.1021/ja012009m.

- (10).For examples, see: Miller JA, Negishi E.-i. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:5863. Sabarre A, Love J. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3941. doi: 10.1021/ol8012843.

- (11).For examples, see: Taber DF, Christos TE, Neubert TD, Batra D. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:9673. Tiefenbacher K, Mulzer J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:2548. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705303.

- (12).The combination of Et3N and a silyl triflate has been found in our laboratory to mediate nickel-catalyzed reactions of simple olefins. Ng S-S, Jamison TF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14194. doi: 10.1021/ja055363j. Ho C-Y, Ng S-S, Jamison TF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5362. doi: 10.1021/ja061471+. Ho C-Y, Jamison TF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:782. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603907. Matsubara R, Jamison TF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6880. doi: 10.1021/ja101186p.

- (13).See Supporting Information for details.

- (14).The discrepancy between the high (100%) conversion of the benzyl bromide and the low (20%) yield of product is believed to be due to nucleophilic displacement of the benzyl bromide by Et3N to form the insoluble triethylammonium salt.

- (15).GC or NMR yields are given for cases where product volatility made isolation difficult.

- (16).The successful use of m-CF3C6H4CH2Cl in a nickel(0)-catalyzed cross coupling reaction has been reported previously: Lipshutz BH, Bulow G, Lowe RF, Stevens KL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:5512.

- (17).For experimental details and NMR spectra, see Supporting Information.

- (18).(a) Bartsch E, Dinjus E, Fischer R, Uhilig E. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1977;433:5. [Google Scholar]; (b) Carmona E, Marín JM, Paneque M, Poveda ML. Organometallics. 1987;6:1757. [Google Scholar]; (c) Carmona E, Paneque M, Poveda ML. Polyhedron. 1989;8:285. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Similar nickel complexes have been unambiguously characterized by X-ray diffraction analyses. Ascenso JR, Carrondo MAAFDT, Dias AR, Gomes PT, Piedade MFM, Romao CC. Polyhedron. 1989;8:2449. Albers I, Álvarez E, Cámpora J, Maya CM, Palma P, Sánchez LJ, Passaglia E. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004;689:833. Anderson TJ, Vicic DA. Organometallics. 2004;23:623.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.