Abstract

Prenatal development is highly sensitive to maternal drug use due to the vulnerability for disruption of the fetal brain where the ongoing neurodevelopmental, resulting in lifelong consequences that can enhance risk for psychiatric disorders. Cannabis and cigarettes are the most commonly used illicit and licit substances, respectively, among pregnant women. While the behavioral consequences of prenatal cannabis and cigarette exposure have been well-documented in epidemiological and clinical studies, only recently have investigations into the molecular mechanisms associated with the developmental impact of early drug exposure been addressed. This article reviews the literature relevant to long-term gene expression disturbances in the human fetal brain in relation to maternal cannabis and cigarette use. To provide translational insights, we discuss animal models in which protracted molecular consequences of prenatal cannabis and cigarette exposure can be better explored and enable future evaluation of epigenetic pathways such as DNA methylation and histone modification that could potentially maintain abnormal gene regulation and related behavioral disturbances. Altogether, this information may help to address the current gaps of knowledge regarding the impact of early drug exposure that set in motion lifelong molecular disturbances that underlie vulnerability to psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: Prenatal, fetal, marijuana, nicotine, epigenetics

Introduction

The insidious intractable nature of drug abuse, which is characterized by the inability to stop drug use despite its negative consequences, has far-reaching implications for pregnant women. The prenatal period is particularly sensitive to the effects of drugs due to the dynamic neurobiological events that occur during gestation to ensure proper patterning of the nervous sy stem. These processes can be disrupted by maternal drug use and can have lifelong consequences. In North America, marijuana (Cannabis sativa) is the most commonly abused illicit drug among pregnant women (~4%), while cigarettes are the most frequently used licit substance (~16%) (SAMHSA, 2006). Similar prevalence rates are noted in European countries for prenatal cannabis exposure (~2–5%) (Fergusson et al., 2002; Lozano et al., 2007; El Marroun et al., 2008), reaching even up to 13% in high-risk populations (Williamson et al., 2006), but there is greater cigarette smoking (~30%) by pregnant women (Troe et al., 2008). While significant epidemiological studies have established that these substances can be harmful to the developing fetus (Richardson et al., 1995; Fried & Smith, 2001; Fried & Watkinson, 2001; Porath & Fried, 2005; Huizink & Mulder, 2006b), there is still relatively little information as to what extent such early developmental drug exposure can have long-lasting effects on the adult brain. Such information is critical given that it is now acknowledged that most mental disorders are developmental in nature, thus insults such as drug exposure during early development could alter neurobiological processes, inducing molecular disturbances that enhance neuropsychiatric susceptibility later in life.

In this review, we outline behavioral and molecular brain alterations documented in the offspring of women with cannabis and cigarette use during pregnancy. Furthermore, we explore results obtained from animal models using the main psychoactive component of cannabis and cigarette smoke, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabidiol (THC) and nicotine, respectively, to provide greater neurobiological insights into the long-lasting effects of early developmental drug insult.

Behavioral consequences of maternal cannabis and cigarette use on human offspring

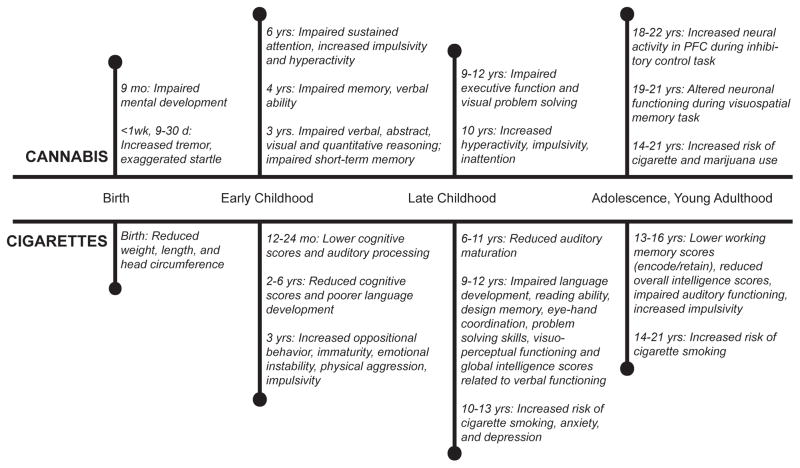

Various studies have evaluated the behavioral effects of prenatal exposure to drugs in offspring of women who smoked cannabis and/or cigarettes when pregnant. Since multiple review articles have already addressed phenotypic effects (Fried & Smith, 2001; Langley et al., 2005; Huizink & Mulder, 2006a; Pauly & Slotkin, 2008; Shea & Steiner, 2008; Jutras-Aswad et al., 2009), we provide only a general overview of key findings. The long-term consequences of prenatal cannabis and cigarette exposure on neurodevelopmental outcome have been primarily assessed by two ongoing longitudinal investigations (Figure 1). The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study, which was initiated in 1978, collects neurobehavioral data from offspring of a low-risk, middle-class population of women who smoked cigarettes and marijuana during pregnancy (Fried et al., 2003). The Maternal Health Practices and Child Development Project, which began in 1982, focuses on the long-term behavioral consequences of prenatal marijuana and alcohol exposure in a low-income African-American population in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Goldschmidt et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Overview of developmental effects associated with prenatal cannabis and cigarette exposure in human subjects. Data compiled from two longitudinal studies Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study and Maternal Health Practices and Childhood Development Project that followed offspring from mothers who used marijuana or cigarettes during pregnancy that are representative of other epidemiological studies. Maternal cannabis and cigarette use is clearly associated with neurobehavioral disturbances that persist into adulthood. Overall, in utero cannabis and cigarette exposure is characterized by impaired cognitive functioning, impulsivity, hyperactivity, and increased risk of developing an addiction disorder.

Data from these two cohorts suggest that cannabis-induced neurobehavioral alterations can be detected in newborns (<1 week old) as well as during later stages of child development. Offspring exposed to cannabis in utero show impairments in specific functional domains including cognitive deficits, impairments in inhibitory control, as well as increased sensitivity to drugs of abuse later in life as detailed in Figure 1 (Day et al., 1994; Fried, 1996; Fried et al., 2002; Day et al., 2006; Willford et al., 2010; Day et al., 2011). It has been well documented that prenatal cigarette exposure also leads to developmental impairments from infancy through adolescence. Offspring exposed to tobacco in utero score lower on intelligence tests, have impaired cognitive functioning, and reduced auditory processing. Moreover, multiple studies have shown that prenatal cigarette exposure leads to increased impulsivity, increased incidence of conduct disorders, and serves as a risk factor for developing multiple neuropsychiatric diseases including anxiety, depression, attention deficit disorder, and addiction (Fried et al., 1983; Fried et al., 1992; Fried, 1993; 1996; Fried et al., 1997; Fried, 1998; Cornelius et al., 2000; Ernst et al., 2001; Fried, 2002; Langley et al., 2005; Cornelius et al., 2011a; Cornelius et al., 2011b).

Overall, these epidemiological and clinical studies clearly emphasize that prenatal cannabis and cigarette exposure leads to long-term behavioral disturbances associated with increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring. Such findings naturally raise the question as to what are the molecular pathophysiological events that underlie the disturbances.

Molecular impairments due to maternal cannabis and cigarette use in the human fetal brain

Unfortunately few investigations have directly examined the human fetal brain given the obvious challenges of conducting such studies. In an attempt to fill this significant gap of knowledge, we developed a post-mortem human fetal brain collection of midgestational subjects (17–22 weeks) with maternal cannabis and cigarette exposure (Hurd et al., 2005). Using this resource, insights into the molecular and biochemical alterations associated with in utero drug exposure on human neurodevelopment could be explored. While our studies have primarily focused on cannabis exposure in this cohort of subjects, some women in the cannabis and control groups also smoked cigarettes, making it possible to begin to evaluate neurobiological patterns potentially related to cigarettes as compared to cannabis. Neurobiological systems related to the above behavioral phenotypes are components of the dopamine, opioid neuropeptide and cannabinoid systems within the striatal and amygdala brain regions. Development of these circuits plays an important role in regulatory processes relevant to the behavioral consequences of prenatal cannabis and cigarette exposure.

Endocannabinoid System

The cannabinoid receptor (CB1R) is the primary molecular target of THC, the psychoactive component of cannabis (Pertwee, 2008). Signaling within the endocannabinoid system dynamically controls neuronal hardwiring during prenatal ontogeny relevant to the development of neural pathways such as the corticostriatothalamic circuit and numerous cortical regions (Berghuis et al., 2007; Harkany et al., 2008; Mulder et al., 2008), which are implicated in addiction (Schmidt et al., 2005; Centonze et al., 2006; Kalivas et al., 2006) and psychiatric disorders (Schwartz et al., 1996; Foerde et al., 2008; Killgore et al., 2008; Harrison et al., 2009). The CB1R mRNA is detected early in gestation and in contrast to the adult brain in which the CB1R is widely distributed, CB1R expression has a heterogenous distribution during early development with expression evident in mesocorticolimbic structures such as the amygdaloid complex, hippocampus, and ventral striatum (Wang et al., 2003). Moreover, the CB1R sites expressed in the human fetal brain are also functional during prenatal development (Mato et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2003; Dow-Edwards et al., 2006). Despite significant disturbances noted in other neuronal systems described below, no alteration was detected on CB1R mRNA expression in relation to prenatal cannabis exposure in multiple brain areas (Wang et al., 2004). However, potential disturbance of receptor function or in other components of the endocannabinoid signaling cannot be excluded.

Dopamine

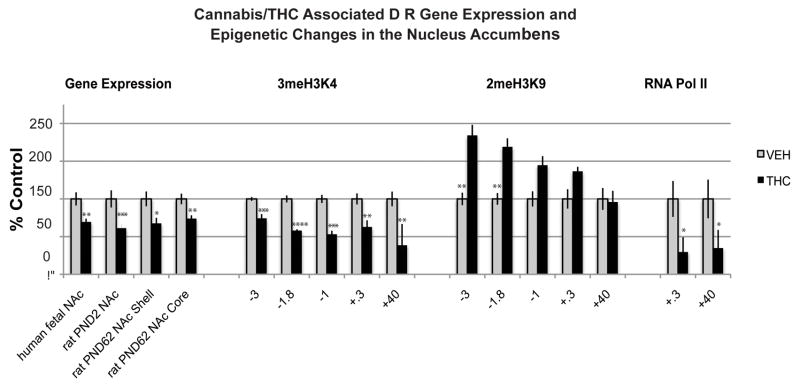

Dopaminergic genes are of particular interest in relation to prenatal cannabis and cigarette exposure since dopamine impairment has been highly implicated in the neurobiology of addiction disorders (Volkow et al., 2004; Pierce & Kumaresan, 2006; Le Foll et al., 2009). Moreover, dopaminergic neurons are expressed early in life. Dopaminergic cell bodies in the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra pars compacta have been detected in the human fetal brain as early as the 5th embryonic week (Verney et al., 1991). In the human fetus, dopamine receptor 1 (DRD1) and dopamine receptor 2 (DRD2) mRNA, as well as dopamine 1 (D1R) and dopamine 2 (D2R) protein and binding sites have been documented by week 12 in the striatum (Kumar & Sastry, 1992). In addition, components of the dopamine system are anatomically linked to the CB1R. For example, CB1Rs are co-expressed with dopaminergic D1Rand D2R on medium spiny neurons in the dorsal striatum, known to play a role in motor function and habit formation, and the ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens; NAc), which regulates reward-related behaviors (Haber, 2003). Dopaminergic receptors, particularly the D2R subtype, have been linked with addiction risk in humans. For example, imaging studies of drug abusers consistently report reduced levels of striatal D2Rs (Volkow et al., 2004). Similarly, human genetic studies link variants of the D2R gene to drug addiction phenotypes related to nicotine, alcohol, opiates and psychostimulant abuse (Le Foll et al., 2009). Interestingly, studies of our human fetal specimens with maternal cannabis exposure also revealed a decrease of DRD2 mRNA expression (Dinieri et al., 2011) (Figure 2). This DRD2 impairment was specific to the mesolimbic NAc since no alterations were evident in the dorsal striatum. The DRD2 mRNA levels in the NAc negatively correlated with maternal report of cannabis use. These effects were selective since mRNA levels of the dopamine DRD1 receptor subtype was not altered in the striatum of subjects exposed to cannabis in utero.

Figure 2. Mesolimbic dopamine D2R gene is vulnerable to prenatal cannabis exposure.

Prenatal cannabis affects dopamine D2R gene expression in the nucleus accumbens of the human midgestational fetus exposed to cannabis in utero. The effects are mimicked in the prenatal THC animal model studied at postnatal day 2 (PND2; comparable to the midgestation human fetal period) and the early developmental disturbances on the Drd2 mRNA expression persist into adulthood (PND62) and are mediated by epigenetic modifications at the Drd2 promoter. Data modified from (Dinieri et al., 2011) 2meH3K9, di-methylation of lysine 9 on histone H3; 3meH3K4, tri-methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3; KB, kilobases; RNA Poly II, RNA Polymerase II; TSS, transcription start site. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001 vs control subjects. Black bars, THC exposed group; white bars, vehicle-exposed group; kb, kilobases; TSS, transcription start site.

Intriguingly, abnormal DRD2 mRNA expression was also observed in the amygdala of the human fetal subjects with in utero cannabis exposure (Wang et al., 2004). Given that the amygdala and NAc are key mesolimbic structures important for emotional regulation, cannabis-induced disturbances in D2-related mesocorticolimbic neuronal populations that could be highly relevant to vulnerability to addiction and psychiatric disorders.

Opioid neuropeptides

There is significant evidence in support of a strong interaction between the cannabinoid and opioid systems, especially in relation to reward and addictive behaviors (Cossu et al., 2001; Valverde et al., 2001; Ghozland et al., 2002). The endogenous opioid system consists of three opioid peptide precursor genes encoding enkephalins (preproENK, PENK), dynorphins (preproDYN, PDYN) and β-endorphin, as well as three receptor genes encoding mu-opiod receptor (μOR), delta-opioid receptor (∂OR), and kappa-opioid receptor (κOR) (Akil et al., 1984). Dynorphin peptides are primary targets for κORs that are linked to dysphoria and negative mood states (Pfeiffer et al., 1986; Bals-Kubik et al., 1993), whereas enkephalins mainly target μOR and ∂OR that are associated with reward (Shippenberg et al., 1987; Bals-Kubik et al., 1993).

In the human brain, PDYN- and PENK-positive neurons are present in the striatum from at least 12 weeks of development (Brana et al., 1995), and opioid receptors are apparent by at least midgestation (Magnan & Tiberi, 1989; Wang et al., 2006; Tripathi et al., 2008). Studies of human fetal subjects exposed to cannabis revealed that PENK-containing neurons appeared to be more sensitive to prenatal cannabis exposure than cells containing PDYN. PENK mRNA levels were decreased in the striatum in association with cannabis exposure and was directly correlated to the amount of maternal use, whereas PDYN levels were not significantly related to in utero cannabis exposure (Wang et al., 2006). It is important to note that striatal PENK mRNA expression, particularly in the rostral region, was also associated with maternal alcohol use (Dinieri et al., 2011) which is an important consideration when interpreting the alterations ascribed to cannabis-related disruption of PENK expression. However, in contrast to the specific disturbances noted for cannabis, alcohol exposure generally lead to more global changes on multiple genes. For example, prenatal alcohol exposure was also significantly associated with decreased expression of DRD1 and DRD2 mRNA levels in the dorsal striatum (Dinieri et al., 2011). Maternal alcohol use also had a broader neurobiological impact particularly on the PDYN/kOR system (see(Wang et al., 2006).

Interestingly, although PDYN gene expression in the human fetal striatum is not related to maternal cannabis use, its expression in the NAc appears to be associated with cigarette exposure (Dinieri et al., 2011). There is a negative correlation observed with the amount of reported maternal cigarette smoking and NAc PDYN mRNA expression levels. PDYN striatal neurons are highly implicated in facilitating motivated behavior and in regulating mood (Akil et al., 1984). Aside from the PDYN disturbances, maternal cigarette use was not associated with expression levels of the other opioid or dopamine markers examined, thus far suggesting that the effect of maternal cannabis is highly significant and affects specific genes in our human fetal postmortem cohort.

Opioid receptors

Of the opioid receptor genes studied, κOR had the highest striatal levels in the midgestational human brain as assessed by in situ hybridization histochemistry. However, cannabis exposure was not associated with alterations of κOR mRNA expression in the striatum but its expression was most affected by maternal alcohol use (Wang et al., 2006). Examination of opioid expression throughout other forebrain structures revealed increased μOR mRNA expression in the amygdala of cannabis-exposed fetuses as well as reduced κOR mRNA in the mediodorsal subdivision of the thalamus, the most limbic-related nucleus of that structure (Wang et al., 2006). No other opioid receptor alterations were detected in relation to maternal cannabis intake and none showed significant relationship to cigarette exposure.

Other neural substrates

It is expected that cannabis and cigarettes could influence multiple neural systems, not only those examined above. In particular, the cholinergic system may be influenced by prenatal cigarette and cannabis exposure, which has known roles in differentiation, axonal guidance, synaptic formation, and autonomic control (Role & Berg, 1996; Kenny et al., 2000). Nicotine exerts its pharmacological action via stimulation of nicotinic acetylcholinergic receptors (nAChRs) that are widely distributed in the brain. Abnormal levels of nicotinic receptors subunits have been detected in the cerebellum, medulla, and pons of cigarette-exposed first trimester human fetuses (Falk et al., 2005). Dysfunction of these brain stem regions resulting in sudden infant death syndrome is strongly correlated with maternal cigarette use during pregnancy and altered gene expression of receptor subunits may be one of the contributing factor to brainstem failure in these infants (Matturri et al., 2004; Huizink & Mulder, 2006a). Specifically, in the first trimester fetal brain, the level of nAChR subunit α4 is increased in the pons and, α4 and α7 receptors are reduced in the fetal cerebellum. Within the medulla, there was an age related increase of nicotinic α4 that was not found in cigarette-exposed fetal tissue. In addition to nAChRs, muscarinic receptor expression m1, m2, and m3 were also altered in the pons and cerebellum, during early fetal development as well (Falk et al., 2005).

To our knowledge, there is a gap in the scientific literature regarding the impact of prenatal cannabis exposure on the cholingeric system. There is though one report of a reduction of choline acetyltransferase, which catalyzes the synthesis of acetylcholine, as a consequence of THC exposure in an in vitro fetal rat telencephalon mixed primary cell culture model. However, much is still unknown about potential consequences of in vivo prenatal exposure.

Overall, the findings observed to date emphasize the discrete dysfunction of mesocorticolimbic (D2R, μOR, and κOR) and striatal (D2R and PENK) neuronal populations with prenatal cannabis exposure and mesolimbic opioid (PDYN) disturbance with cigarette exposure. Within the cholinergic system, tobacco exposure alters both nicotinic (α4 and α7) and muscarinic receptors (m1, m2, and m3) within brainstem and cerebellum regions. Clearly, multiple neuronal systems need to be studied in more depth to better understand the molecular pathophysiology of maternal cannabis and cigarette use on the human fetal brain especially for neuronal systems related to neurocognitive aspects, impulsivity, and addiction vulnerability. Such studies would provide neurobiological insights underlying the behavioral disturbances observed in human offspring exposed to these drugs during prenatal development.

Molecular consequences of early developmental cannabis exposure - animal models

Despite the apparent associations of cannabis exposure to discrete neurobiological alterations in the human fetal brain, the specificity of such disturbances attributed to cannabis must be verified especially in light of potential polysubstance exposure in humans. Moreover, cannabis consists of many compounds including over 60 cannabinoids one of which is THC (Taura et al., 2007). Additionally, cannabis preparations contain differing amounts of these various cannabinoids, confound the psychoactive effects of the drug (Van der Kooy et al., 2008). Thus, interpretation of the human data is significantly enhanced by ascertaining the relevance of the drug changes specifically to THC, the main psychoactive component of cannabis. Considering the noted enduring effects of prenatal drug exposure on behavior, the question is also raised as to what the long-lasting neuronal effects associated with the behavioral disturbances are. Animal models are extremely useful tools to help resolve such issues. We and others have shown that prenatal and perinatal exposure to cannabinoid compounds lead to long-lasting effects into adulthood on neuronal systems linked to dopamine and opioid neuropeptide disturbances observed in the human fetuses (Table 1). For example, rats with prenatal THC treatment have a similar reduction of D2R mRNA expression in the NAc (Figure 2), but not dorsal striatum, at the same developmental time period as that examined in the human fetus and the mesolimbic D2R gene impairment persists long-term into adulthood (Dinieri et al., 2011). Moreover, a behavioral study showed that adult rats exposed to doses of THC relevant to human consumption during the perinatal period exhibit altered D2R dopamine autoreceptor sensitivity as evidenced by an enhanced reduction of locomotor activity in response to dopamine receptor agonists targeting the presynaptic receptor (Moreno et al., 2003). These behavioral effects were most prominent in males.

Table 1. Long Term Gene Expression Related to Prenatal THC or Nicotine Exposure in Experimental Animal Models.

Overview of studies examining the effects of exposure to prenatal THC and nicotine, the psychoactive components of cannabis and cigarettes, respectively, on mRNA expression during adolescence (PND35) and in adulthood (PND62-150).

| Treatment | Subject | Age at testing | Effects on mRNA expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ9-THC 5 mg/kg Daily oral GD5-PND24 | Wistar rat ♂/♀ | PND70 | ♂ Cnr1: ↑ in HIP ♀ Cnr1: no Δ in CTX, CP, NAc, HIP, AMG |

(Garcia-Gil et al., 1999) |

| Δ9-THC 0.15 mg/kg Daily i.v., GD5-PND2 | Long Evans rat ♂ | PND62 | ♂ Drd2: ↓ in NAc core and shell | (Dinieri et al., 2011) |

| Δ9-THC 0.15 mg/kg Daily i.v. GD5-PND2 | Long Evans rat ♂ | PND62 | ♂ Penk: no Δ in CP, ↑ in NAc core, ↑ in NAc shell, ↑ in AMG ♂ Pdyn: no Δ in DS, NAc core, NAc shell |

(Spano et al., 2007) |

| Nicotine 3 mg/kg Oral GD4-GD15 | Sprague- Dawley rat ♂ | PND35 |

mRNA expression changes in CAMs ↓ in CP: Actn1b, Bai3a, Cdh13a , Cntn4a, Cntn5a Cntn6a Ctnna1b Ctnna2b Ctnnb1b Ctnnd2ab Csmd1a, Dscam, Fynb, Lphn3a, Nlgn1, Postn ↑ in NAc: Postn ↓ in NAc: Ptprda ↑ in PFC: Postn ↓ in PFC: Dscam Nlgn1 Nrxn3 ↓ in Amy: Ncam1, Pecam1, Sgcza |

(Cao et al., 2011) |

| Nicotine 2mg/kg Daily oral GD1-PND14 | Sprague- Dawley rat ♂/♀ | PND35 | nAchR subunit a3, a4, a5, b4 in ↓ VTA nAchR subunit a3 in ↑ NAc |

(Chen et al., 2005) |

| Nicotine 100 mg/l oral GD7-PND28 | Wistar rats | PND35 | M1 & M2 muscarinic receptor: no Δ PFC, midbrain, HIP, cerebellum, brainstem | (Zhu et al., 1998) |

| Nicotine 0.1 mg/kg oral PND1-21 and PND8- P21 | Sprague- Dawley ♂/♀ | PND35 | α2, α3, α4, α7, α2 nAchR: no Δ PFC, HIP, striatum, brainstem, thalamus | (Miao et al., 1998) |

| Nicotine 0.06/ml Oral | Lister hooded rats ♂ | PND150 | ↑Drd5: Striatum TH, NR4A2, DAT1, DRD4: no Δ striatum, PFC |

(Schneider et al., 2011) |

| Nicotine 2.1 mg/day Daily i.v. GD4-PND1 | Sprague- Dawley ♂/♀ | PND150 | ♀↑ AT1R: total brain tissue ♀♂↓ AT2R: total brain tissue |

(Mao et al., 2008) |

In addition, the alteration of PENK observed in human cannabis-exposed fetuses is also reproduced by prenatal THC exposure in neonatal rats and an allostatic upregulation, again specifically localized to the NAc, is observed in adulthood (Spano et al., 2007). Adult animals with prenatal cannabinoid drug exposure self-administer more heroin, particularly when stressed, show greater opiate reward and also exhibit enhanced emotional reactivity (Trezza et al., 2008). Other studies have also demonstrated dopamine, opioid and behavioral impairments with early exposure to CB1 agonists that are in line with the above observations (Walters & Carr, 1986; Rodriguez de Fonseca et al., 1991; Navarro et al., 1994; Corchero et al., 1998; Perez-Rosado et al., 2000; Perez-Rosado et al., 2002; Schneider, 2009).

In addition to specific mesolimbic disturbances in association with perinatal THC exposure, there also appears to be continued specificity in regard to the striatal populations affected by prenatal drug exposure. For example, striatonigral cells specifically express D1R and PDYN whereas striatopallidal neurons express D2R and PENK (Heiman et al., 2008) and in contrast to PENK and D2R, no significant alterations were found on PDYN or D1R mRNA expression levels, in rats with prenatal THC exposure (Spano et al., 2007; DiNieri et al., 2011). Similar to the human fetuses, no significant alterations were detected in relation to the CB1R level of receptor binding, or GTP coupling, although there was a tendency for increased CB1R agonist (WIN 55,2212)-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the core subregion of the NAc (Spano et al., 2007). Overall, a number of the animal studies confirm findings in the human cannabis-exposed fetuses such that prenatal exposure to THC is associated with specific mesolimbic and striatopallidal disturbances that persist into adulthood. Indeed, prenatal cannabis exposure disrupts the expression of dopamine and opioid related genes and the resulting impairments persist into adolescence and adulthood (Garcia-Gil et al., 1999; Perez-Rosado et al., 2000; Perez-Rosado et al., 2002; Spano et al., 2007).

Molecular consequences of early developmental nicotine exposure - animal models

Although various animal models have examined the effects of nicotine directly in adult animals, few studies have evaluated the long-term impact of prenatal nicotine exposure on gene expression. Numerous groups have identified behavioral differences in perinatally nicotine treated animals that present later in life. Briefly, elevated plus maze behavioral testing demonstrated that nicotine-treated adolescent (PND40) and young adult (PND60) rats showed an increase in anxiety-related behavior. Furthermore, prenatal nicotine treated animals yielded lower scores in cognitive and memory testing (Vaglenova et al., 2008). Compared to saline exposed rats, prenatal nicotine-treated adolescent rats demonstrated an increase in both drug (cocaine self-administration) and natural reward (sucrose pellets) behaviors (Franke et al., 2008). Phenotypic changes correlate well with human epidemiological studies (Figure 1), thus strengthening the findings identified in animal models.

Of the developmental nicotine studies that focus on molecular events, the majority of investigations were conducted during the perinatal period of the rodent and the results have emphasized significant early developmental disturbances of a number of neuronal systems (Miao et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1998; Xu et al., 2001). Of the studies addressing the long-term consequences, a few have directly examined gene expression in the brain induced by prenatal nicotine exposure (Table 1). Chen et al. demonstrated that prenatal nicotine treatment leads to reduced mRNA levels of the nAChR subunits α3, α4, α5, and β4 in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of adolescent rats and increased α3 mRNA in the NAc; both the VTA and NAc are highly implicated in reward and addiction (Chen et al., 2005). Although Miao et al. failed to observe long-term alteration of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor mRNA expression in striatal and mesocorticolimbic brain regions in adult animals following perinatal nicotine exposure (equivalent to the third trimester in human gestation), there were nevertheless noted alterations in the receptor activity in these regions (Miao et al., 1998).

Long-term impairments in other neuronal systems have also been reported. For example, a recent study observed an increase in dopamine receptor 5 mRNA expression in the striatum of adult rats with prenatal nicotine suggesting long-term dopaminergic disturbance with early nicotine exposure (Schneider et al., 2011). In addition, Cao et al (Cao et al., 2011), provided evidence that prenatal nicotine exposure leads to long-term gene expression alterations of neural cell adhesion 1 and Neuroligin1 cell adhesion molecules that modulate synapse development and function in the brain (Dalva et al., 2007; Hines et al., 2008; Xiao et al., 2009; Jung et al., 2010). Interestingly, dysfunction of several of these cell adhesion molecules has been implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders (Vawter, 2000; Fujita et al., 2010; Cichon et al., 2011). Although we focus on investigations that have examined the long-term impact on gene expression, it is important to note that several studies have also observed long-term disturbances following prenatal nicotine on protein or receptor function (Seidler et al., 1992; Xu et al., 2001; Kane et al., 2004; Vaglenova et al., 2008) and it is predicted that some of these disturbances could relate to dysregulation of gene expression. Such reports emphasize impairment of dopamine (Xu et al., 2001; Schneider et al., 2011), cholinergic (Navarro et al., 1989; Nordberg et al., 1991; van de Kamp & Collins, 1994; Tizabi et al., 1997), and serotonergic (Muneoka et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2001) systems. No animal studies to our knowledge have thus far examined opioid neuronal system in relation to prenatal nicotine exposure.

Epigenetic mechanisms underlying the long-term effects of prenatal drug exposure

A fundamental question is how prenatal THC or nicotine exposure causes alterations in gene expression that are maintained into adulthood, long after the initial drug exposure period in utero. As discussed above, both THC and nicotine causes substantial changes in gene expression levels with abnormalities persisting long into the life of the individual. One potential mechanism by which prenatal drug exposure could lead to long-lasting changes in behavior is through inducing alterations in epigenetic gene regulation mechanisms in the brain, which would be propagated throughout development stably enough to cause enduring phenotypical abnormalities. ‘Epigenetic’ refers to mechanisms that modulate gene expression without altering the genetic code. The epigenome is influenced by the environment and thus is a highly relevant biological candidate to maintain aberrant neuronal processing as a result of drug exposure during prenatal development. Despite the vulnerability of the developing brain to drugs, most epigenetic addiction studies have focused on the adult brain so limited information currently exists as to epigenetic effects associated with developmental drug exposure. In this section, we discuss several epigenetic processes that will merit future investigation as the most likely candidate mechanisms involved in mediating the long-term effects of prenatal cannabis and cigarette exposure.

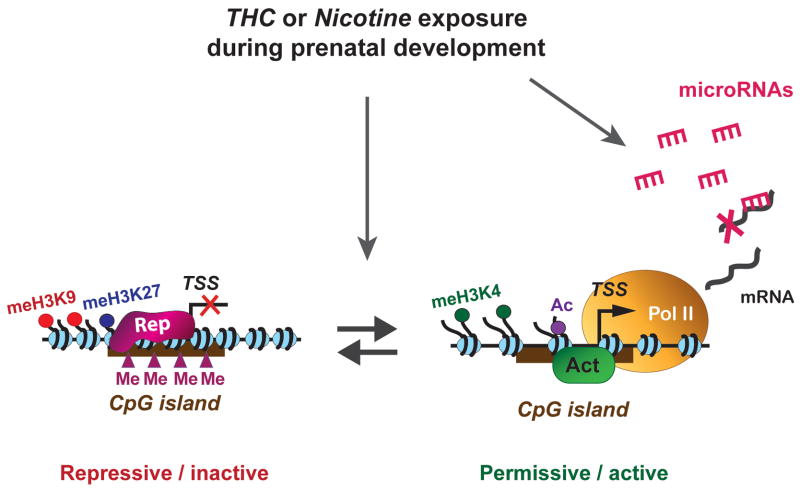

Epigenetic modifications that can regulate gene expression levels include microRNAs, DNA methylation and post-translational modifications of nucleosomal histones (Figure 3) (Saetrom et al., 2007; Ooi & Wood, 2008; Guil & Esteller, 2009). The role of microRNAs in neuronal development has been widely documented and a number of observations have indicated, for example, that cocaine addiction can change the normal composition of striatal microRNAs in adult animals (Eipper-Mains et al., 2011). Interestingly, ethanol treatment during the prenatal period has been associated with teratogenesis and changes in microRNA composition in the mouse fetal brain, leading to mental retardation later in the life of the offspring (Wang et al., 2009). It will be interesting to assess whether prenatal cannabis and nicotine exposure affects neuronal microRNA populations and related gene regulatory processes.

Figure 3. A few possible epigenetic regulatory mechanisms that can be disrupted by maternal cannabis and nicotine u se, leading to persistent abnormal gene expression levels.

Changes in DNA methylation at CpG islands, along with post-translational modification of histones, can create ‘repressive’ (transcriptionally silent) and ‘permissive’ (transcriptionally active) chromatin states. These states are dynamically regulated by the activities of DNA or histone modifying and chromatin remodeling enzymes and exposure to drugs during prenatal development is likely to disrupt the balance of repressive and permissive mechanisms. In silent chromatin, methylation of H3 lysine 9 (meK9) and lysine 27 (meK27) is known to be associated with the binding of repressor complexes (Rep) and this leads to chromatin condensation and decreased accessibility of the gene. In the permissive state, methylation of H3 lysine 4 (meK4) and acetylation (ac) is often associated with the binding of activator proteins (Act), generating increased accessibility for the recruitment of the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery (Pol II). Prenatal THC exposure was recently shown to enhance dimethylation of H3K9 of the dopamine D2 R gene promoter in adult animals relevant to the THC-induced long-term impairment on gene expression (see Figure 3). MicroRNAs can regulate mRNA levels post-transciptionally and changes in the neuronal microRNA populations due to developmental drug exposure may lead to disturbances in protein function. TSS, transcription start site.

DNA methylation is an epigenetic mark that is known to be particularly stable throughout development. Maternal stress or nutritional deficiencies have been reported to cause long-lasting impairments in DNA methylation (Ronald et al., 2010; Jousse et al., 2011; Tarantino et al., 2011), and it is conceivable that exposure to psychoactive drugs during prenatal development could induce similar abnormalities. In fact, maternal cocaine administration has indeed been shown to trigger changes in DNA methylation that are detectable in hippocampal neurons of neonatal and adolescent mice (Novikova et al., 2008). Several groups have identified atypical DNA methylation patterns within the placenta (Suter et al., 2010) of cigarette smoke-exposed infants and altered methylation of CpG islands at specific gene loci has been reported as long-term effects associated with prenatal nicotine exposure in somatic tissues (Toro et al., 2008; Breton et al., 2009; Suter et al., 2010; Toledo-Rodriguez et al., 2010). These observations raise the important question whether similar epigenetic disturbances occur in the brain that could possibly explain the development of abnormal behavioral tendencies.

Most studies related to drug abuse in the adult brain have focused on histone modification, which is broadly implicated in the dynamic regulation of transcriptionally repressive (inactive) and permissive (active) states (Figure 3). Covalent modifications of histones play a major part in epigenetic regulation and histone acetylation, methylation and phosphorylation have been implicated in gene regulation and neurobiological disturbances related to drug abuse (Li et al., 2007; Nestler, 2009). Published data thus far has indicated that increases in acetylation and phosphorylation are transient and appear to be associated with the quick activation of genes in response to drug exposure rather than the maintenance of an altered transcription state (Kumar et al., 2005). Histone methylation is known to maintain stable gene expression alterations. In addition, the regulation of histone H3 modification is unique because methylation of distinct residues can have the opposite effect on transcription (Bannister & Kouzarides, 2005). Especially interesting is the developmental role of H3K9 dimethylation and H3K27 trimethylation in the maintenance of life-long tissue-specific gene silencing patterns (Horn & Peterson, 2006; Swigut & Wysocka, 2007). This raises the possibility of histone methylation playing a role in the propagation of perturbed gene transcription states induced by developmental cannabis and cigarette exposure.

Our studies of offspring from the prenatal THC rat model have begun to uncover such disturbances in histone modification in the adult brain. The reduction of Drd2 mRNA transcript levels in the NAc of cannabis-exposed human fetuses and in neonatal rats with prenatal THC exposure, together with the persistence of the change into adulthood in rats, indicated that the observed downregulation of Drd2 gene expression may be achieved via epigenetic processes. Examining various marks with antagonistic roles in histone H3 regulation revealed increased levels of dimethylation of lysine 9 on histone H3 (2meH3K9), a repressive mark, as well as decreased RNA polymerase II association with the gene in the NAc which are consistent with reduction of the Drd2 gene expression (Figure 2). The methylation profile of histone H3 on the Drd2 gene was specific since there was no alteration of 2meH3K9 observed at the Drd1 gene (Dinieri et al., 2011). These findings suggest that maternal cannabis use alters the developmental regulation of mesolimbic D2R in offspring through epigenetic mechanisms, specifically histone lysine methylation, and the ensuing reduction of D2R may contribute to increased vulnerability to drug abuse later in life. To date, no other epigenetic studies to our knowledge have been published regarding the effects of prenatal cannabis exposure on the brain.

Summary and future perspectives

The studies reviewed here emphasize the sensitive nature of the prenatal developmental period, during which cannabis and cigarette exposure can set into motion epigenetic alterations that contribute to long-term disturbances in mesocorticolimbic gene regulation, thereby laying a foundation for increased vulnerability to addiction and potentially other psychiatric disorders. While a large number of human longitudinal studies have shown significant behavioral disturbances with in utero cannabis or cigarette exposure, the lack of molecular investigations in the human brain as well as the limited knowledge regarding their long-term impact significantly hinders insights about the neurobiology underlying risk for psychiatric disorders. This, however, provides an important opportunity to expand our current knowledge regarding the molecular mechanisms underlying the long-term consequences of prenatal cannabis and cigarette exposure. Current state-of-the-art approaches to explore in-depth epigenetic mechanisms will no doubt provide significant advances within this field.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse DA023214 (YLH), DA12030 (YLH) and F31-DA031559 (CVM).

Abbreviations

- Actn1

Actinin, alpha 1

- AMY

Amygdala:

- AT1R

Angiotension Receptor 1

- AT2R

Angiotension Receptor 2

- Bai3

Brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 3

- Cdh13

Cadherin 13

- CB1R

Cannabinoid receptor

- Ctnna1

Catenin (cadherin associated protein), alpha 1

- Ctnna2

Catenin (cadherin associated protein), alpha 2

- Ctnnb1b

Catenin (cadherin associated protein), beta 1

- Ctnnd2

Catenin (cadherin associated protein), delta 2

- CP

Caudate-Putamen

- CAMs

Cell Adhesion Molecules

- Cntn4

Contactin 4

- Cntn5

Contactin 5

- Cntn6

Contactin 6

- CTX

Cortex

- Csmd1a

CUB and Sushi multiple domains 1

- THC

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- ∂OR

Delta-opioid receptor

- Dat1

Dopamine transporter 1

- D1R

Dopamine receptor 1 protein

- Drd1

Dopamine Receptor 1 gene

- D2R

Dopamine Receptor 2 protein

- Drd2

Dopamine Receptor 2 gene

- Drd4

Dopamine Receptor 4

- Drd5

Dopamine Receptor 5

- Dscam

Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule

- Fyn

Fyn proto-oncogene

- GD

Gestational Day

- HIP

Hippocampus

- kOR

Kappa Opioid Receptor

- μOR

Mu Opioid Receptor

- NAc

Nucleus Accumbens

- Nr4a2

Nuclear Receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2:

- Lphn3

Latrophilin 3

- nAchR

Nicotinic Cholinergic Receptor

- Ncam1

Neural cell adhesion molecule1

- Nrxn3

Neurexin3

- Nlgn1

Neuroligin1

- Postn

Periostin, osteoblast specific factor

- Pecam1

Platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1, PND, Postnatal day

- PFC

Prefrontal cortex

- Pdyn

Prodynorphin

- PENK

Proenkephalin

- Ptprd

Receptor-type protein tyrosine phophatse D

- Sgcz

Sarcoglycan zeta

- TH

Tyrosine hydroxylase

- VTA

Ventral Tegmental Area

References

- Akil H, Watson SJ, Young E, Lewis ME, Khachaturian H, Walker JM. Endogenous opioids: biology and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bals-Kubik R, Ableitner A, Herz A, Shippenberg TS. Neuroanatomical sites mediating the motivational effects of opioids as mapped by the conditioned place preference paradigm in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Reversing histone methylation. Nature. 2005;436:1103–1106. doi: 10.1038/nature04048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghuis P, Rajnicek AM, Morozov YM, Ross RA, Mulder J, Urban GM, Monory K, Marsicano G, Matteoli M, Canty A, Irving AJ, Katona I, Yanagawa Y, Rakic P, Lutz B, Mackie K, Harkany T. Hardwiring the brain: endocannabinoids shape neuronal connectivity. Science. 2007;316:1212–1216. doi: 10.1126/science.1137406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brana C, Charron G, Aubert I, Carles D, Martin-Negrier ML, Trouette H, Fournier MC, Vital C, Bloch B. Ontogeny of the striatal neurons expressing neuropeptide genes in the human fetus and neonate. J Comp Neurol. 1995;360:488–505. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton CV, Byun HM, Wenten M, Pan F, Yang A, Gilliland FD. Prenatal tobacco smoke exposure affects global and gene-specific DNA methylation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:462–467. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0135OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Dwyer JB, Mangold JE, Wang J, Wei J, Leslie FM, Li MD. Modulation of cell adhesion systems by prenatal nicotine exposure in limbic brain regions of adolescent female rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:157–174. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710000179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze D, Costa C, Rossi S, Prosperetti C, Pisani A, Usiello A, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB, Calabresi P. Chronic cocaine prevents depotentiation at corticostriatal synapses. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Parker SL, Matta SG, Sharp BM. Gestational nicotine exposure reduces nicotinic cholinergic receptor (nAChR) expression in dopaminergic brain regions of adolescent rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:380–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichon S, Muhleisen TW, Degenhardt FA, Mattheisen M, Miro X, Strohmaier J, Steffens M, Meesters C, Herms S, Weingarten M, Priebe L, Haenisch B, Alexander M, Vollmer J, Breuer R, Schmal C, Tessmann P, Moebus S, Wichmann HE, Schreiber S, Muller-Myhsok B, Lucae S, Jamain S, Leboyer M, Bellivier F, Etain B, Henry C, Kahn JP, Heath S, Hamshere M, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ, Craddock N, Schwarz M, Vedder H, Kammerer-Ciernioch J, Reif A, Sasse J, Bauer M, Hautzinger M, Wright A, Mitchell PB, Schofield PR, Montgomery GW, Medland SE, Gordon SD, Martin NG, Gustafsson O, Andreassen O, Djurovic S, Sigurdsson E, Steinberg S, Stefansson H, Stefansson K, Kapur-Pojskic L, Oruc L, Rivas F, Mayoral F, Chuchalin A, Babadjanova G, Tiganov AS, Pantelejeva G, Abramova LI, Grigoroiu-Serbanescu M, Diaconu CC, Czerski PM, Hauser J, Zimmer A, Lathrop M, Schulze TG, Wienker TF, Schumacher J, Maier W, Propping P, Rietschel M, Nothen MM. Genome-wide association study identifies genetic variation in neurocan as a susceptibility factor for bipolar disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:372–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corchero J, Garcia-Gil L, Manzanares J, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ, Fuentes JA, Ramos JA. Perinatal delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol exposure reduces proenkephalin gene expression in the caudate-putamen of adult female rats. Life Sci. 1998;63:843–850. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, De Genna NM, Leech SL, Willford JA, Goldschmidt L, Day NL. Effects of prenatal cigarette smoke exposure on neurobehavioral outcomes in 10-year-old children of adolescent mothers. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2011a;33:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, Goldschmidt L, De Genna NM, Larkby C. Long-term Effects of Prenatal Cigarette Smoke Exposure on Behavior Dysregulation Among 14-Year-Old Offspring of Teenage Mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2011b doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0766-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, Leech SL, Goldschmidt L, Day NL. Prenatal tobacco exposure: is it a risk factor for early tobacco experimentation? Nicotine Tob Res. 2000;2:45–52. doi: 10.1080/14622200050011295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossu G, Ledent C, Fattore L, Imperato A, Bohme GA, Parmentier M, Fratta W. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice fail to self-administer morphine but not other drugs of abuse. Behav Brain Res. 2001;118:61–65. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalva MB, McClelland AC, Kayser MS. Cell adhesion molecules: signalling functions at the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:206–220. doi: 10.1038/nrn2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day NL, Goldschmidt L, Thomas CA. Prenatal marijuana exposure contributes to the prediction of marijuana use at age 14. Addiction. 2006;101:1313–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day NL, Leech SL, Goldschmidt L. The effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on delinquent behaviors are mediated by measures of neurocognitive functioning. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2011;33:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day NL, Richardson GA, Geva D, Robles N. Alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco: effects of prenatal exposure on offspring growth and morphology at age six. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:786–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinieri JA, Wang X, Szutorisz H, Spano SM, Kaur J, Casaccia P, Dow-Edwards D, Hurd YL. Maternal Cannabis Use Alters Ventral Striatal Dopamine D2 Gene Regulation in the Offspring. Biol Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow-Edwards DL, Benveniste H, Behnke M, Bandstra ES, Singer LT, Hurd YL, Stanford LR. Neuroimaging of prenatal drug exposure. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2006;28:386–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eipper-Mains JE, Kiraly DD, Palakodeti D, Mains RE, Eipper BA, Graveley BR. microRNA-Seq reveals cocaine-regulated expression of striatal microRNAs. RNA. 2011;17:1529–1543. doi: 10.1261/rna.2775511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Marroun H, Tiemeier H, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Mackenbach JP, Steegers EA, Verhulst FC, van den Brink W, Huizink AC. Demographic, emotional and social determinants of cannabis use in early pregnancy: The Generation R study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Moolchan ET, Robinson ML. Behavioral and neural consequences of prenatal exposure to nicotine. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:630–641. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk L, Nordberg A, Seiger A, Kjaeldgaard A, Hellstrom-Lindahl E. Smoking during early pregnancy affects the expression pattern of both nicotinic and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in human first trimester brainstem and cerebellum. Neuroscience. 2005;132:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Northstone K. Maternal use of cannabis and pregnancy outcome. Bjog. 2002;109:21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerde K, Poldrack RA, Khan BJ, Sabb FW, Bookheimer SY, Bilder RM, Guthrie D, Granholm E, Nuechterlein KH, Marder SR, Asarnow RF. Selective corticostriatal dysfunction in schizophrenia: examination of motor and cognitive skill learning. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:100–109. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke RM, Park M, Belluzzi JD, Leslie FM. Prenatal nicotine exposure changes natural and drug-induced reinforcement in adolescent male rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2952–2961. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried P. Cigarette smoke exposure and hearing loss. JAMA. 1998;280:963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried P, Watkinson B, James D, Gray R. Current and former marijuana use: preliminary findings of a longitudinal study of effects on IQ in young adults. CMAJ. 2002;166:887–891. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA. Prenatal exposure to tobacco and marijuana: effects during pregnancy, infancy, and early childhood. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1993;36:319–337. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199306000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA. Behavioral outcomes in preschool and school-age children exposed prenatally to marijuana: a review and speculative interpretation. NIDA Res Monogr. 1996;164:242–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA. Adolescents prenatally exposed to marijuana: examination of facets of complex behaviors and comparisons with the influence of in utero cigarettes. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42:97S–102S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA, Buckingham M, Von Kulmiz P. Marijuana use during pregnancy and perinatal risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;146:992–994. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90989-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA, O’Connell CM, Watkinson B. 60- and 72-month follow-up of children prenatally exposed to marijuana, cigarettes, and alcohol: cognitive and language assessment. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1992;13:383–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA, Smith AM. A literature review of the consequences of prenatal marihuana exposure. An emerging theme of a deficiency in aspects of executive function. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(00)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA, Watkinson B. Differential effects on facets of attention in adolescents prenatally exposed to cigarettes and marihuana. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:421–430. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA, Watkinson B, Gray R. Differential effects on cognitive functioning in 13- to 16-year-olds prenatally exposed to cigarettes and marihuana. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2003;25:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(03)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA, Watkinson B, Siegel LS. Reading and language in 9- to 12-year olds prenatally exposed to cigarettes and marijuana. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1997;19:171–183. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(97)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita E, Dai H, Tanabe Y, Zhiling Y, Yamagata T, Miyakawa T, Tanokura M, Momoi MY, Momoi T. Autism spectrum disorder is related to endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by mutations in the synaptic cell adhesion molecule, CADM1. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e47. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gil L, Romero J, Ramos JA, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ. Cannabinoid receptor binding and mRNA levels in several brain regions of adult male and female rats perinatally exposed to delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;55:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghozland S, Matthes HW, Simonin F, Filliol D, Kieffer BL, Maldonado R. Motivational effects of cannabinoids are mediated by mu-opioid and kappa-opioid receptors. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1146–1154. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01146.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, Willford J, Day NL. Prenatal marijuana exposure and intelligence test performance at age 6. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:254–263. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318160b3f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guil S, Esteller M. DNA methylomes, histone codes and miRNAs: tying it all together. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN. The primate basal ganglia: parallel and integrative networks. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;26:317–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkany T, Mackie K, Doherty P. Wiring and firing neuronal networks: endocannabinoids take center stage. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison BJ, Soriano-Mas C, Pujol J, Ortiz H, Lopez-Sola M, Hernandez-Ribas R, Deus J, Alonso P, Yucel M, Pantelis C, Menchon JM, Cardoner N. Altered corticostriatal functional connectivity in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1189–1200. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman M, Schaefer A, Gong S, Peterson JD, Day M, Ramsey KE, Suarez-Farinas M, Schwarz C, Stephan DA, Surmeier DJ, Greengard P, Heintz N. A translational profiling approach for the molecular characterization of CNS cell types. Cell. 2008;135:738–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines RM, Wu L, Hines DJ, Steenland H, Mansour S, Dahlhaus R, Singaraja RR, Cao X, Sammler E, Hormuzdi SG, Zhuo M, El-Husseini A. Synaptic imbalance, stereotypies, and impaired social interactions in mice with altered neuroligin 2 expression. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6055–6067. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0032-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn PJ, Peterson CL. Heterochromatin assembly: a new twist on an old model. Chromosome Res. 2006;14:83–94. doi: 10.1007/s10577-005-1018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC, Mulder EJ. Maternal smoking, drinking or cannabis use during pregnancy and neurobehavioral and cognitive functioning in human offspring. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006a;30:24–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC, Mulder EJH. Maternal smoking, drinking or cannabis use during pregnancy and neurobehavioral and cognitive functioning in human offspring. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006b;30:24–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd YL, Wang X, Anderson V, Beck O, Minkoff H, Dow-Edwards D. Marijuana impairs growth in mid-gestation fetuses. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2005;27:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jousse C, Parry L, Lambert-Langlais S, Maurin AC, Averous J, Bruhat A, Carraro V, Tost J, Letteron P, Chen P, Jockers R, Launay JM, Mallet J, Fafournoux P. Perinatal undernutrition affects the methylation and expression of the leptin gene in adults: implication for the understanding of metabolic syndrome. FASEB J. 2011 doi: 10.1096/fj.11-181792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung SY, Kim J, Kwon OB, Jung JH, An K, Jeong AY, Lee CJ, Choi YB, Bailey CH, Kandel ER, Kim JH. Input-specific synaptic plasticity in the amygdala is regulated by neuroligin-1 via postsynaptic NMDA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4710–4715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001084107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutras-Aswad D, DiNieri JA, Harkany T, Hurd YL. Neurobiological consequences of maternal cannabis on human fetal development and its neuropsychiatric outcome. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;259:395–412. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0027-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Peters J, Knackstedt L. Animal models and brain circuits in drug addiction. Mol Interv. 2006;6:339–344. doi: 10.1124/mi.6.6.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane VB, Fu Y, Matta SG, Sharp BM. Gestational nicotine exposure attenuates nicotine-stimulated dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens shell of adolescent Lewis rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:521–528. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PJ, File SE, Rattray M. Acute nicotine decreases, and chronic nicotine increases the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in rat hippocampus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;85:234–238. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WD, Gruber SA, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Abnormal corticostriatal activity during fear perception in bipolar disorder. Neuroreport. 2008;19:1523–1527. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328310af58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Choi KH, Renthal W, Tsankova NM, Theobald DE, Truong HT, Russo SJ, Laplant Q, Sasaki TS, Whistler KN, Neve RL, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Chromatin remodeling is a key mechanism underlying cocaine-induced plasticity in striatum. Neuron. 2005;48:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar BV, Sastry PS. Dopamine receptors in human foetal brains: characterization, regulation and ontogeny of [3H]spiperone binding sites in striatum. Neurochem Int. 1992;20:559–566. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(92)90035-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley K, Rice F, van den Bree MB, Thapar A. Maternal smoking during pregnancy as an environmental risk factor for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder behaviour. A review. Minerva Pediatr. 2005;57:359–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Gallo A, Le Strat Y, Lu L, Gorwood P. Genetics of dopamine receptors and drug addiction: a comprehensive review. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20:1–17. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283242f05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano J, Garcia-Algar O, Marchei E, Vall O, Monleon T, Giovannandrea RD, Pichini S. Prevalence of gestational exposure to cannabis in a Mediterranean city by meconium analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:1734–1737. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnan J, Tiberi M. Evidence for the presence of mu- and kappa- but not of delta-opioid sites in the human fetal brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1989;45:275–281. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C, Zhang H, Xiao D, Zhu L, Ding Y, Zhang Y, Wu L, Xu Z, Zhang L. Perinatal nicotine exposure alters AT 1 and AT 2 receptor expression pattern in the brain of fetal and offspring rats. Brain Res. 2008;1243:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mato S, Del Olmo E, Pazos A. Ontogenetic development of cannabinoid receptor expression and signal transduction functionality in the human brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1747–1754. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matturri L, Ottaviani G, Alfonsi G, Crippa M, Rossi L, Lavezzi AM. Study of the brainstem, particularly the arcuate nucleus, in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and sudden intrauterine unexplained death (SIUD) Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2004;25:44–48. doi: 10.1097/01.paf.0000113813.83779.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H, Liu C, Bishop K, Gong ZH, Nordberg A, Zhang X. Nicotine exposure during a critical period of development leads to persistent changes in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors of adult rat brain. J Neurochem. 1998;70:752–762. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70020752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M, Trigo JM, Escuredo L, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Navarro M. Perinatal exposure to delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol increases presynaptic dopamine D2 receptor sensitivity: a behavioral study in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:565–575. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder J, Aguado T, Keimpema E, Barabas K, Ballester Rosado CJ, Nguyen L, Monory K, Marsicano G, Di Marzo V, Hurd YL, Guillemot F, Mackie K, Lutz B, Guzman M, Lu HC, Galve-Roperh I, Harkany T. Endocannabinoid signaling controls pyramidal cell specification and long-range axon patterning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8760–8765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803545105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muneoka K, Ogawa T, Kamei K, Mimura Y, Kato H, Takigawa M. Nicotine exposure during pregnancy is a factor which influences serotonin transporter density in the rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;411:279–282. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00925-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro HA, Seidler FJ, Eylers JP, Baker FE, Dobbins SS, Lappi SE, Slotkin TA. Effects of prenatal nicotine exposure on development of central and peripheral cholinergic neurotransmitter systems. Evidence for cholinergic trophic influences in developing brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:894–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Hernandez ML, Ramos JA, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ. Motor behavior and nigrostriatal dopaminergic activity in adult rats perinatally exposed to cannabinoids. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;47:47. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Epigenetic mechanisms in psychiatry. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:189–190. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg A, Zhang XA, Fredriksson A, Eriksson P. Neonatal nicotine exposure induces permanent changes in brain nicotinic receptors and behaviour in adult mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;63:201–207. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikova SI, He F, Bai J, Cutrufello NJ, Lidow MS, Undieh AS. Maternal cocaine administration in mice alters DNA methylation and gene expression in hippocampal neurons of neonatal and prepubertal offspring. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi L, Wood IC. Regulation of gene expression in the nervous system. Biochem J. 2008;414:327–341. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly JR, Slotkin TA. Maternal tobacco smoking, nicotine replacement and neurobehavioural development. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:1331–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Rosado A, Gomez M, Manzanares J, Ramos JA, Fernandez-Ruiz J. Changes in prodynorphin and POMC gene expression in several brain regions of rat fetuses prenatally exposed to Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol. 2002;4:211. doi: 10.1080/10298420290023936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Rosado A, Manzanares J, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Ramos JA. Prenatal Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol exposure modifies proenkephalin gene expression in the fetal rat brain: sex-dependent differences. Brain research Developmental brain research. 2000;120:77. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Ligands that target cannabinoid receptors in the brain: from THC to anandamide and beyond. Addiction biology. 2008;13:147–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer A, Brandt V, Herz A. Psychotomimesis mediated by kappa opiate receptors. Science. 1986;233:774–776. doi: 10.1126/science.3016896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Kumaresan V. The mesolimbic dopamine system: the final common pathway for the reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:215–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porath AJ, Fried PA. Effects of prenatal cigarette and marijuana exposure on drug use among offspring. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2005;27:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Day NL, Goldschmidt L. Prenatal alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use: infant mental and motor development. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1995;17:479–487. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(95)00006-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Cebeira M, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ, Navarro M, Ramos JA. Effects of pre- and perinatal exposure to hashish extracts on the ontogeny of brain dopaminergic neurons. Neuroscience. 1991;43:713–723. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90329-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role LW, Berg DK. Nicotinic receptors in the development and modulation of CNS synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald A, Pennell CE, Whitehouse AJ. Prenatal Maternal Stress Associated with ADHD and Autistic Traits in early Childhood. Front Psychol. 2010;1:223. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saetrom P, Snove O, Jr, Rossi JJ. Epigenetics and microRNAs. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:17R–23R. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e318045760e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. SAMHSA Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt ED, Voorn P, Binnekade R, Schoffelmeer AN, De Vries TJ. Differential involvement of the prelimbic cortex and striatum in conditioned heroin and sucrose seeking following long-term extinction. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2347–2356. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M. Cannabis use in pregnancy and early life and its consequences: animal models. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;259:383–393. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Ilott N, Brolese G, Bizarro L, Asherson PJ, Stolerman IP. Prenatal exposure to nicotine impairs performance of the 5-choice serial reaction time task in adult rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1114–1125. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz BL, Rosse RB, Veazey C, Deutsch SI. Impaired motor skill learning in schizophrenia: implications for corticostriatal dysfunction. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:241–248. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler FJ, Levin ED, Lappi SE, Slotkin TA. Fetal nicotine exposure ablates the ability of postnatal nicotine challenge to release norepinephrine from rat brain regions. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1992;69:288–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea AK, Steiner M. Cigarette smoking during pregnancy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:267–278. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Bals-Kubik R, Herz A. Motivational properties of opioids: evidence that an activation of delta-receptors mediates reinforcement processes. Brain Res. 1987;436:234–239. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spano MS, Ellgren M, Wang X, Hurd YL. Prenatal cannabis exposure increases heroin seeking with allostatic changes in limbic enkephalin systems in adulthood. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:554–563. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter M, Abramovici A, Showalter L, Hu M, Shope CD, Varner M, Aagaard-Tillery K. In utero tobacco exposure epigenetically modifies placental CYP1A1 expression. Metabolism. 2010;59:1481–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swigut T, Wysocka J. H3K27 demethylases, at long last. Cell. 2007;131:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarantino LM, Sullivan PF, Meltzer-Brody S. Using animal models to disentangle the role of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental influences on behavioral outcomes associated with maternal anxiety and depression. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:44. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taura F, Sirikantaramas S, Shoyama Y, Morimoto S. Phytocannabinoids in Cannabis sativa: recent studies on biosynthetic enzymes. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4:1649–1663. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizabi Y, Popke EJ, Rahman MA, Nespor SM, Grunberg NE. Hyperactivity induced by prenatal nicotine exposure is associated with an increase in cortical nicotinic receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;58:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00461-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Rodriguez M, Lotfipour S, Leonard G, Perron M, Richer L, Veillette S, Pausova Z, Paus T. Maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with epigenetic modifications of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor-6 exon in adolescent offspring. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B:1350–1354. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro R, Leonard G, Lerner JV, Lerner RM, Perron M, Pike GB, Richer L, Veillette S, Pausova Z, Paus T. Prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking and the adolescent cerebral cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1019–1027. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza V, Campolongo P, Cassano T, Macheda T, Dipasquale P, Carratu MR, Gaetani S, Cuomo V. Effects of perinatal exposure to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on the emotional reactivity of the offspring: a longitudinal behavioral study in Wistar rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;198:529–537. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi A, Khurshid N, Kumar P, Iyengar S. Expression of delta- and mu-opioid receptors in the ventricular and subventricular zones of the developing human neocortex. Neurosci Res. 2008;61:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troe EJ, Raat H, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Steegers EA, Verhulst FC, Witteman JC, Mackenbach JP. Smoking during pregnancy in ethnic populations: the Generation R study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1373–1384. doi: 10.1080/14622200802238944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglenova J, Parameshwaran K, Suppiramaniam V, Breese CR, Pandiella N, Birru S. Long-lasting teratogenic effects of nicotine on cognition: gender specificity and role of AMPA receptor function. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;90:527–536. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde O, Noble F, Beslot F, Dauge V, Fournie-Zaluski MC, Roques BP. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol releases and facilitates the effects of endogenous enkephalins: reduction in morphine withdrawal syndrome without change in rewarding effect. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1816–1824. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Kamp JL, Collins AC. Prenatal nicotine alters nicotinic receptor development in the mouse brain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;47:889–900. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kooy F, Pomahacova B, Verpoorte R. Cannabis smoke condensate I: the effect of different preparation methods on tetrahydrocannabinol levels. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20:801–804. doi: 10.1080/08958370802013559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vawter MP. Dysregulation of the neural cell adhesion molecule and neuropsychiatric disorders. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;405:385–395. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00568-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verney C, Zecevic N, Nikolic B, Alvarez C, Berger B. Early evidence of catecholaminergic cell groups in 5- and 6-week-old human embryos using tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase immunocytochemistry. Neurosci Lett. 1991;131:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90351-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Swanson JM. Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction: results from imaging studies and treatment implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:557–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters DE, Carr LA. Changes in brain catecholamine mechanisms following perinatal exposure to marihuana. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;25:763–768. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90384-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LL, Zhang Z, Li Q, Yang R, Pei X, Xu Y, Wang J, Zhou SF, Li Y. Ethanol exposure induces differential microRNA and target gene expression and teratogenic effects which can be suppressed by folic acid supplementation. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:562–579. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Dow-Edwards D, Anderson V, Minkoff H, Hurd YL. In utero marijuana exposure associated with abnormal amygdala dopamine D2 gene expression in the human fetus. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Dow-Edwards D, Anderson V, Minkoff H, Hurd YL. Discrete opioid gene expression impairment in the human fetal brain associated with maternal marijuana use. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6:255–264. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Dow-Edwards D, Keller E, Hurd YL. Preferential limbic expression of the cannabinoid receptor mRNA in the human fetal brain. Neuroscience. 2003;118:681–694. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willford JA, Chandler LS, Goldschmidt L, Day NL. Effects of prenatal tobacco, alcohol and marijuana exposure on processing speed, visual-motor coordination, and interhemispheric transfer. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2010;32:580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson S, Jackson L, Skeoch C, Azzim G, Anderson R. Determination of the prevalence of drug misuse by meconium analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91:F291–292. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.078642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao MF, Xu JC, Tereshchenko Y, Novak D, Schachner M, Kleene R. Neural cell adhesion molecule modulates dopaminergic signaling and behavior by regulating dopamine D2 receptor internalization. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14752–14763. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4860-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Seidler FJ, Ali SF, Slikker W, Jr, Slotkin TA. Fetal and adolescent nicotine administration: effects on CNS serotonergic systems. Brain Res. 2001;914:166–178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02797-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Taniguchi T, Konishi Y, Mayumi M, Muramatsu I. Nicotine administration decreases the number of binding sites and mRNA of M1 and M2 muscarinic receptors in specific brain regions of rat neonates. Life Sci. 1998;62:1089–1098. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]