Abstract

Objectives

To compare the dimensional psychopathology in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder (BP) with offspring of community control parents as assessed by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).

Methods

Offspring of parents with BP, who were healthy or had no non-BP disorders (n = 319) and bipolar spectrum disorders (n = 35), and offspring of community controls (n = 235) ages 6–18 years old were compared using the CBCL, the CBCL-Dysregulation Profile (CBCL-DP), and a sum of the CBCL items associated with mood lability. The results were adjusted for multiple comparisons and any significant between-group demographic and clinical differences in both biological parents and offspring.

Results

With few exceptions, several CBCL (e.g., Total, Internalizing, and Aggression Problems), CBCL-DP, and mood lability scores in non-BP offspring of parents with BP were significantly higher than in offspring of control parents. In addition, both groups of offspring showed significantly lower scores in most scales when compared with offspring of parents with BP who already developed BP. Similar results were obtained when analyzing the rates of subjects with CBCL T-scores that were two standard deviations or higher above the mean.

Conclusions

Even before developing BP, offspring of parents with BP had more severe and higher rates of dimensional psychopathology than offspring of control parents. Prospective follow-up studies in non-BP offspring of parents with BP are warranted to evaluate whether these dimensional profiles are prodromal manifestations of mood or other disorders and can predict those who are at higher risk to develop BP.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, bipolar offspring, psychopathology, Child Behavior Checklist, dysregulation profile, mood lability

Bipolar disorder (BP) is a debilitating illness in youth that increases the risk for suicide, psychosis, and substance abuse, and severely affects development and psychosocial functioning (1, 2). Retrospective studies have consistently shown that up to 60% of adult patients began to have symptoms of BP during their youth (3–5). However, it takes an average of 10 years to correctly identify and initiate treatment (3). Early diagnosis and treatment in BP youth is critical not only to stabilize mood but also to prevent an unrecoverable loss in psychosocial development and education (2). Therefore, studying youth at risk for BP is very important in order to better understand early manifestations of the illness that may in turn inform early intervention and prevention efforts (2, 6).

The single strongest factor for developing BP is high family loading for this disorder (3, 6). Recent studies report that the risk of developing BP in offspring of parents with BP is as high as 20% (7). Thus, carefully evaluating the offspring of parents with BP and comparing their psychopathology with that of the offspring of control parents may provide very important information about the early presentations of BP.

Current studies have mainly evaluated the presence of categorical psychiatric disorders in offspring of parents with BP. These studies have shown that offspring of parents with BP are indeed specifically at higher risk to develop BP, but they are also at risk for other psychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety and disruptive behavior disorders (DBD) (8–11). However, it appears from few available studies that offspring of parents with BP have prodromal mood and behavioral symptoms (8–10) and different patterns of neurocognitive functioning (12) and brain activation (13) before they may develop the full threshold BP. Therefore, since categorical approaches may not have sufficient sensitivity to capture behavioral correlates of psychopathology in youth at risk for BP who may be experiencing subthreshold psychopathology (14), studies evaluating dimensional psychopathology with validated dimensional scales may be beneficial.

One of these scales, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was used in few studies to evaluate the dimensional psychopathology of offspring of parents with BP (15–18). These studies showed that offspring of parents with BP had higher CBCL scores on internalizing and externalizing problems when compared with healthy offspring of healthy parents (16) and a Dutch normative sample (17, 18). In addition, the dimensional psychopathology was more severe in offspring of parents who already developed BP when compared with healthy offspring of healthy parents (16) and non-BP offspring of parents with BP (15). However, the results of these studies are constrained by several limitations such as the inclusion of small samples (15, 16), not including control parents (15, 18) or including only healthy control parents (16), and not taking into account the effects of potential confounding factors such as the child’s (16, 17), parent’s (15–18), and co-parent’s non-BP psychopathology (15–18).

The CBCL has also been used to evaluate the dimensional psychopathology in youth who have already been diagnosed with BP. These studies have shown that youth with BP have significantly more psychopathology than children with no non-BP disorders and healthy controls (19–21). Moreover, some researchers have shown that the sum of Anxious/Depressed, Attention Problems, and Aggressive Behaviors subscales [the so called Pediatric or Juvenile Bipolar Profile (CBCL-PBP/JBP)] runs in families (22–24) and is significantly elevated in children with BP (25). However, high scores in the CBCL and the CBCL-PBP/JBP appear to be a nonspecific marker for severe psychopathology or mood dysregulation instead of being specific for BP (21, 24, 26, 27), and as a consequence some authors have suggested changing its name to the CBCL-Dysregulation Profile (CBCL-DP) (28, 29).

In a prior communication, the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS) (30) reported that, after adjusting for confounding factors, offspring of parents with BP showed higher rates of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV(DSM-IV) (31) bipolar spectrum, DBD, and anxiety disorders when compared with offspring of community controls. The main goal of this study was to extend these prior categorical findings by evaluating the dimensional psychopathology ascertained though the CBCL to offspring of parents with BP who at intake were healthy or had non-BP psychopathology and offspring of community control parents. In addition, above results will be compared with offspring of parents with BP who at intake already had BP. Based on the existing literature, we hypothesized that offspring of parents with BP, particularly those offspring with BP, will have higher levels of dimensional psychopathology than offspring of community control parents.

Methods

Sample

The methodology for the BIOS has been reported in detail elsewhere (30). In summary, parents with BP were recruited through advertisement (53%), adult BP studies (31%), and outpatient clinics (16%). There were no differences in BP subtype, age of BP onset, and rates of no non-BP disorders based on recruitment source. Parents were required to fulfill the DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder (BP-I) or bipolar II disorder (BP-II) (31). Exclusion criteria included current or lifetime diagnoses of schizophrenia, mental retardation, mood disorders secondary to substance abuse, medical conditions, or medications, and living more than 200 miles away from Pittsburgh. BIOS recruited 233 parents with BP and their 388 offspring aged 6–18 years. Of these subjects, 224 parents completed the CBCL in regard to their 354 offspring. As described in detail below, 190 offspring of the parents with BP were healthy or had no non-BP disorders and 35 offspring of parents with BP who had bipolar spectrum disorders [13 offspring with BP-I/BP-II and 22 offspring with BP-not otherwise specified (BP-NOS)]. Control parents consisted of healthy parents or parents with non-BP pathology from the community, group matched by age, sex, and neighborhood with BP parents. The control parents had the same exclusion criteria as the parents with BP, but they could not have BP or have a first-degree relative with BP. BIOS recruited 143 control parents and their 251 offspring. Of these, 136 parents completed the CBCL in regards to their 235 offspring. There were no demographic and clinical differences in the parents and their offspring between those with and without the CBCL.

Clinical measures

After Institutional Review Board approval, consent was obtained from the parent and assent from the children. Parents were assessed for psychiatric disorders, family psychiatric history, and other variables such as dimensional psychopathology, and family environment. DSM-IV (31) psychiatric disorders for parents, and biological co-parents who participated in direct interviews (30%), were ascertained through the Structured Clinical Interview-DSM-IV (SCID) (32) plus the attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), DBD, and separation anxiety disorder sections from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL) (33). Socioeconomic status (SES) was ascertained using the Hollingshead scale (34). The Family History–Research Diagnostic Criteria method (FH-RDC) (35) plus ADHD and DBD items from the K-SADS-PL was used to ascertain the psychiatric history of biological co-parents not seen for direct interview. There was no difference in the rates of direct assessments used to obtain the biological co-parent’s psychiatric disorders between BP parents and controls (26.3% versus 27.8%, respectively).

Parents were interviewed about their children and the children were directly interviewed for the presence of lifetime non-mood psychiatric disorders using the K-SADS-PL (33). As per the K-SADS-PL instructions, mood symptoms that were also in common with other psychiatric disorders (e.g., hyperactivity) were not rated as present in the mood sections unless they intensified with the onset of abnormal mood. Comorbid diagnoses were not assigned if they occurred exclusively during a mood episode. All diagnoses were made using the DSM-IV criteria (31). However, since the DSM does not clearly define BP-NOS, operationalized criteria for BP-NOS were utilized (36, 37). Bachelors- or masters-level interviewers completed all assessments after intensive training for all instruments and after ≥ 80% agreement with a certified rater. The overall SCID and K-SADS-PL kappas for psychiatric disorders were ≥ 0.8.

Subjects aged between 6 to 18 years old were administered the 1991 version of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/4–18) (38). The CBCL includes 118 problem behavior items rated from 0 (not at all typical of the child) to 2 (often typical of the child) for the past six months and includes eight subscales (Rule-breaking Behavior, Aggressive Behaviors, Withdrawn/Depressed, Anxious/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems) and three broadband scales [Externalizing Problems (includes Rule-breaking and Aggressive Behaviors), Internalizing Problems (includes Somatic Complaints, Withdrawn/Depressed, and Anxious/Depressed), and Total Problems (includes Externalizing Problems, Internalizing Problems, Social, Thought, and Attention Problems)]. The CBCL-DP is defined as the sum of Anxious/Depressed, Attention Problems, and Aggressive Behaviors subscales (25, 28). Raw scores are summed for component questions of each clinical factor and they are transformed to T-scores (with a floor of 50 for each of the 8 subscales). T-scores ≥ 2 standard deviations (SD) above normal (≥ 70 for the CBCL scales and ≥ 210 for the CBCL-DP phenotype) indicate significant psychopathology (19, 29). Since mood lability appears to be associated with BP (39, 40), the sum of raw scores for some CBCL items (impulsivity, irritability, sudden changes in mood or feelings, sulks a lot, and temper tantrums or hot temper) was analyzed.

Statistical analysis

As per the CBCL manual instructions (38), raw scores were used to compare the CBCL scores (22) among the three groups of offspring and T-scores were used to evaluate the rates of children with significant psychopathology (e.g., T-scores ≥ 70).

For the comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics and CBCL raw scores among the three groups of offspring, parametric and nonparametric methods were used as appropriate. Similar methods were used to analyze the demographic and clinical characteristics (e.g., DSM psychiatric disorders) of the parents.

Multivariate analysis of variance was used to compare the CBCL, CBCL-DP, and mood lability scores among the three offspring groups. Mixed effects models were developed to compare CBCL scores adjusting for within family correlations and significant demographic and clinical characteristics. In addition, age by group interactions were included in the models in which age was categorized in four classes to better capture possible age-related developmental differences in dimensional psychopathology (41): younger than 9, between 9 and 12, between 13 and 15, and older than 15. All tests were two-sided with a significance level set at 0.05. All pair-wise comparisons were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni corrections.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics in parents

As shown in Table 1, parents with BP were significantly more likely to be living separately and had higher lifetime rates of anxiety disorders, ADHD, DBD, substance use disorders (SUD), and any Axis I disorders than community control parents. Parents with BP with non-BP offspring were significantly more likely to be Caucasian and parents with BP whose offspring had BP were significantly younger and had lower SES than community control parents.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of parents with bipolar disorder (BP) with non-BP offspring, parents with BP with BP offspring, and community control parents

| Parents with BP with non-BP offspring (n = 190) |

Parents with BP with BP offspring (n = 34) |

Control parents (n = 136) |

Statistics | Overall p-values |

Pairwise comparisons (p-values)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 | ||||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 40.0 (7.9) | 37.2 (6.0) | 41.2 (7.2) | F = 4.1 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.02 |

| SES, mean (SD) | 35.5 (14.6) | 30.7 (11.9) | 37.5 (12.5) | F = 3.5 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.56 | 0.03 |

| Race (white) | 89.5 | 82.4 | 77.9 | χ2 = 8.2 | 0.02 | 0.70 | 0.01 | 1.00 |

| Sex (female) | 77.9 | 94.1 | 77.9 | χ2 = 5.0 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.09 |

| Living together (yes) | 51.6 | 38.2 | 67.7 | χ2 = 13.4 | 0.001 | 0.46 | 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Bipolar I disorder | 71.1 | 61.8 | – | – | – | 0.83 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Bipolar II disorder | 29.0 | 38.2 | – | – | – | 0.83 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Depressive disorders | – | – | 27.2 | – | – | – | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Anxiety disorders | 71.1 | 79.4 | 19.9 | χ2 = 94.2 | < 0.01 | 0.95 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| ADHD | 26.8 | 20.6 | 2.9 | χ2 = 32.1 | < 0.01 | 1.00 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| DBD | 34.2 | 41.2 | 7.4 | χ2 = 36.2 | < 0.01 | 1.00 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| SUD | 62.6 | 64.7 | 27.2 | χ2 = 43.3 | < 0.01 | 1.00 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Any Axis I disorder | 100.0 | 100.0 | 53.7 | χ2 = 125.8 | < 0.01 | – | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

Values indicated as percent, except where noted otherwise. SES = socioeconomic status; ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactive disorder; DBD = disruptive behavioral disorders; SUD = substance use disorders.

Pair-wise comparisons show p-values after Bonferroni correction. Group 1 = Parents with BP with non-BP offspring; Group 2 = Parents with BP with BP offspring; Group 3 = control parents.

For the offspring of parents with BP, offspring with versus without BP had significantly more biological co-parents with BP (14.4% versus 3.2%, p < 0.05). In addition, both of these co-parent groups, when compared with biological co-parent of controls, had higher rates of SUD (42.9% versus 35% versus 20.7%, respectively) and DBD (7.1% versus 3.7% versus 1.9%, respectively) (all p-values < 0.05). There were no other significant differences among the biological co-parents.

Demographic and clinical characteristics in offspring

As shown in Table 2, significantly more offspring of community control parents were living with both biological parents compared to non-BP and BP offspring of parents with BP. Both non-BP and BP offspring of parents with BP had significantly higher rates for most psychiatric disorders than offspring of community control parents. Non-BP offspring of parents with BP had significantly lower rates of anxiety disorders, DBD, and any Axis I disorder when compared with BP offspring of parents with BP.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics in non-bipolar disorder (BP) offspring of parents with BP, BP offspring of parents with BP, and offspring of community control parents

| Non-BP offspring of parents with BP (n = 319) |

BP offspring of parents with BP (n = 35) |

Offspring of control parents (n = 235) |

Statistics | Overall p-values |

Pairwise comparisons (p-values)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 | ||||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 11.7 (3.6) | 12.8 (3.1) | 11.8 (3.5) | F = 1.53 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 0.38 |

| Living with both bio-parents | 44.2 | 28.6 | 63.4 | χ2 = 27.41 | < 0.01 | 0.23 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Race (white) | 83.7 | 77.1 | 76.6 | χ2 = 4.61 | 0.10 | 0.98 | 0.11 | 1.00 |

| Sex (female) | 47.3 | 62.9 | 54.9 | χ2 = 5.09 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 1.00 |

| Depressive disorders | 11.6 | – | 3.8 | – | – | 0.10 | < 0.01 | 0.72 |

| Anxiety disorders | 23.2 | 48.6 | 10.2 | χ2 = 34.50 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| ADHD | 23.8 | 37.1 | 14.5 | χ2 = 13.12 | < 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.02 | < 0.01 |

| DBD | 14.4 | 48.6 | 6.8 | χ2 = 46.36 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| SUD | 3.5 | 5.7 | 2.1 | χ2 = 1.68 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.64 |

| Other Axis I disordersb | 17.6 | 25.7 | 11.1 | χ2 = 7.37 | 0.03 | 0.71 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| Any Axis I disorder | 60.8 | 100.0 | 39.6 | χ2 = 55.49 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

Values indicated as percent, except where noted otherwise. ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactive disorder; DBD = disruptive behavioral disorders; SUD = substance use disorders.

Pair-wise comparisons show p-values after Bonferroni correction. Group 1 = Non-BP offspring of parents with BP; Group 2 = BP offspring of parents with BP; Group 3 = offspring of control parents.

Other Axis I disorders = DSM diagnoses (e.g., elimination, tics, and eating disorders) other than BP, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, ADHD, DBD, and SUD.

CBCL, CBCL-DP, and mood lability raw scores

There were no significant differences between the demographic, clinical characteristics, and CBCL scores among youth with BP-I, BP-II, and BP-NOS. Thus, for simplicity, all results presented for the BP subtypes are combined.

All CBCL, CBCL-DP, and mood lability unadjusted scores were significantly higher in non-BP offspring of parents with BP than in offspring of control parents. Also, non-BP offspring had significantly lower unadjusted scores in all CBCL scales, CBCL-DP, and mood lability when compared with BP offspring of parents with BP.

After controlling for between-group differences in demographic factors and rates of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in both biological parents and offspring, non-BP offspring of parents with BP had significantly higher scores compared to offspring of community control parents in the CBCL Total, Internalizing, Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, and Aggressive Behaviors scales and CBCL-DP and mood lability (Table 3). With the exception of Rule-breaking Behavior and Thought Problems, all CBCL, CBCL-DP, and mood lability adjusted scores were significantly lower in non-BP offspring of parents with BP when compared with BP offspring of parents with BP. Finally, with the exception of Rule-breaking Behavior, all CBCL, CBCL-DP and mood lability adjusted scores were significantly higher in BP offspring of parents with BP when compared with offspring of community control parents (all adjusted p-values < 0.05). For all the above analyses, there were no significant age by group interactions.

Table 3.

Mean raw scores of Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL) scales, dysregulation profile, and mood lability items in non-bipolar disorder (BP) offspring of parents with BP, BP offspring of parents with BP, and offspring of community control parents

| Non-BP offspring of parents with BP (n = 319) |

BP offspring of parents with BP (n = 35) |

Offspring of control parents (n = 235) |

Statistics (F) |

Adjusted overall p- valuesa |

Pairwise comparisons (adjusted p-values)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 | ||||||

| CBCL scores | ||||||||

| Total Problems | 33.4 (26.8) | 59.2 (30.1) | 19.6 (19.2) | 50.03 | < 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.01 | < 0.0001 |

| Externalizing | 11.5 (10.3) | 20.9 (10.3) | 7.1 (8.0) | 38.5 | < 0.0001 | 0.0009 | 0.08 | < 0.0001 |

| Internalizing | 10.0 (8.8) | 17.3 (11.8) | 5.2 (5.9) | 45.8 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.01 | < 0.0001 |

| Anxious/Depressed | 5.0 (4.8) | 9.0 (6.7) | 2.5 (3.1) | 45.4 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.03 | < 0.0001 |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 3.3 (3.2) | 5.1 (3.3) | 1.8 (2.2) | 30.8 | 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.015 | 0.0001 |

| Somatic Complaints | 2.2 (2.8) | 4.1 (4.0) | 1.2 (1.9) | 22.3 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.10 | 0.001 |

| Social Problems | 2.3 (2.8) | 4.2 (3.4) | 1.6 (2.2) | 16.7 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.01 |

| Thought Problems | 0.9 (1.7) | 1.7 (2.4) | .5 (1.0) | 12.1 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.60 | 0.02 |

| Attention Problems | 4.3 (4.4) | 7.1 (4.4) | 2.5 (3.2) | 27.5 | 0.0004 | 0.002 | 0.30 | 0.0002 |

| Rule-breaking Behavior | 2.4 (2.8) | 3.9 (2.9) | 1.5 (2.4) | 15.03 | 0.35 | 0.98 | > 0.99 | 0.50 |

| Aggressive Behaviors | 9.1 (8.1) | 17.1 (8.1) | 5.5 (6.1) | 42.9 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.04 | < 0.0001 |

| CBCL-DPc | 16.7 (13.8) | 29.3 (13.0) | 9.8 (10.0) | 46.9 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.02 | < 0.0001 |

| CBCL mood lability itemsd | 3.0 (2.7) | 6 (2.4) | 1.7 (2.0) | 54.7 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.016 | < 0.0001 |

Values indicated as mean (SD).

Overall p-values adjusting for significant demographics and clinical variables among both bio-parents [e.g., age, socioeconomic status, race, living together, anxiety disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), disruptive behavioral disorders (DBD), substance use disorders (SUD), and any Axis I disorder] and offspring [e.g., age and sex in addition to living with both bio-parents, anxiety disorders, ADHD, DBD, other Axis I disorders (e.g., elimination, tics, and eating disorders), and any Axis I disorder].

Pair-wise comparisons show adjusted p-values after Bonferroni correction. Group 1 = non-BP offspring of parents with BP; Group 2 = BP offspring of parents with BP; Group 3 = offspring of control parents.

CBCL-DP = Child Behavior Checklist–Dysregulation Profile (sum of CBCL Anxious/Depressed, Attention Problems, and Aggressive Behaviors subscales).

CBCL mood lability items = CBCL items of impulsivity, irritability, sudden changes in mood or feelings, sulks a lot, and temper tantrums or hot temper.

CBCL and CBCL-DP T-scores

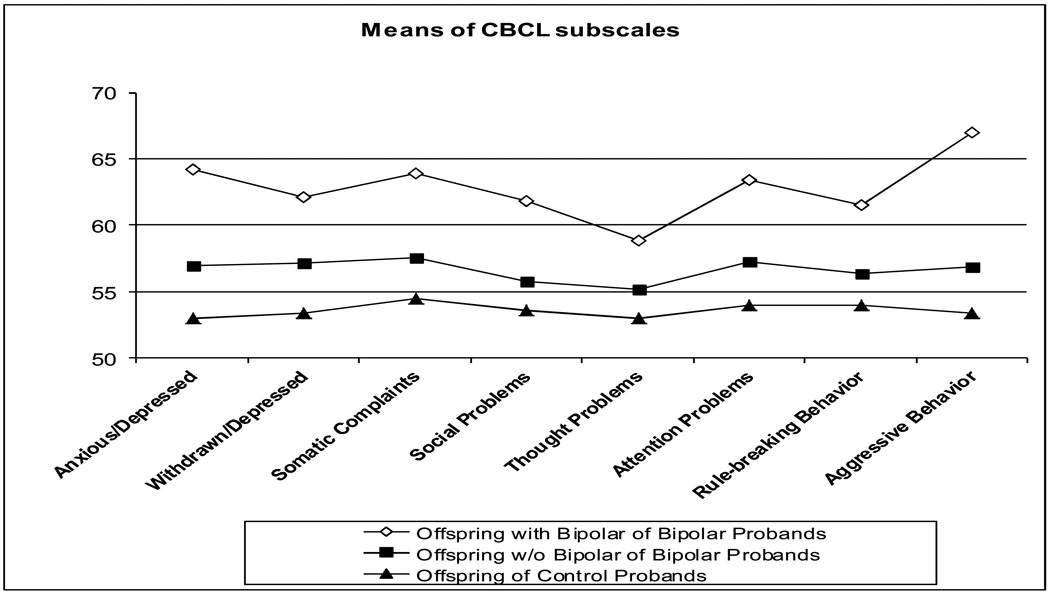

In accordance with the existent literature (19, 21, 42, 43), the presence of significant dimensional psychopathology in the three offspring groups using the cutoff T-scores of the CBCL (≥ 70) (Fig. 1) and the proposed cutoff score for the CBCL-DP (≥ 210) (25) were evaluated. Similar to the results using CBCL raw scores, significantly more non-BP offspring of parents with BP had dimensional psychopathology above the cutoff CBCL T-scores in most scales and CBCL-DP when compared with offspring of community control parents. Also, significantly more BP offspring had dimensional psychopathology above the cutoff CBCL T-scores in most scales and CBCL-DP when compared with the other two offspring groups (for all above noted comparisons adjusted p-values < 0.03).

Fig. 1.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) mean T-scores in non-bipolar disorder (BP) offspring of parents with BP, BP offspring of parents with BP, and offspring of community control parents. T-scores: 55 = 0.5 standard deviations (SD), 60 = 1 SD, 65 = 1.5 SD, and 70 = 2 SD above normal values. Except for Total, Externalizing, and Internalizing broadband scales, a floor of 50 was used for the eight subscales as per the CBCL manual.

Discussion

In this large sample of offspring at high risk to develop BP, after adjusting for confounding factors, offspring of parents with BP showed higher levels of dimensional psychopathology than offspring of the community controls. Specifically, when compared with offspring of community control parents, offspring of parents with BP who were healthy or had non-BP psychopathology showed significantly higher scores in most CBCL subscales, CBCL-DP, and mood lability. In addition, offspring of parents with BP who already developed BP showed significant higher scores in most CBCL subscales, CBCL-DP, and mood lability when compared to the other two offspring groups. Similar results were obtained when the proportion of subjects with CBCL T-scores ≥ 2 SDs above the mean was compared. Thus, there was a stepwise increase in the severity of dimensional psychopathology between the three offspring groups with offspring of parents with BP who already developed BP having most severe psychopathology, offspring of controls having the least, and non-BP offspring of parents with BP being in between (Fig. 1). Longitudinal follow-up studies will determine whether the presence of the dimensional psychopathology would predispose these non-BP offspring to develop mood or other disorders, and more specifically BP.

The results of this study must be considered in the context of certain limitations. The results are cross-sectional and most children have not yet passed through the period of greatest risk for the onset of BP. Similar to the concerns with previous studies (19–21), the CBCL is a parent-rated scale and its scores can be affected by parental bias. Control parents with psychopathology could have been more interested in having their children evaluated through the study and may have had greater knowledge about psychiatric disorders, possibly inflating the rate of psychopathology in their offspring. However, the effects seem to be small in earlier studies (44–46) and the rates of lifetime psychiatric disorders in offspring of control parents in our study were similar to those described in other community studies (47, 48). Lastly, the parents with BP who agreed to participate in BIOS could have had more psychopathology than those who did not participate. The rates of psychiatric disorders in parents with BP in our study were similar to those reported in the adult BP literature (49–51); however, the possibility of residual confounding remains.

Similar to our findings, the few studies that have assessed dimensional psychopathology in BP offspring of parents with BP reported overall significant psychopathology in most of the CBCL scales when compared with healthy offspring of healthy parents (16) and healthy offspring of parents with BP (15). Recent studies in referred samples of youth with BP have shown that high scores on CBCL scales are not specific to BP (26, 28), but reflect the severity of psychopathology associated with BP (26). Thus, it was not surprising to find that offspring of parents with BP who already developed BP showed higher levels of dimensional psychopathology than the other two groups. Of particular attention, consistent with previous studies (15–18), non-BP offspring of parents with BP also had higher levels of dimensional psychopathology and a significantly larger proportion of subjects with elevated T-scores than offspring of the community control parents.

To our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing the CBCL-DP in offspring of parents with BP. Investigations in offspring of parents with BP that have individually evaluated the three CBCL subscales that compose the CBCL-DP have also found high scores in the Anxiety/Depression, Aggression and less consistently, in the Attention subscale when compared with healthy offspring of healthy parents (16), healthy offspring of parents with BP (15), and a Dutch normative sample (17). Available longitudinal studies suggested that the CBCL-DP was highly stable over a five-year follow-up (52) and its presence at intake predicted subsequent BP over seven-year follow-up in ADHD youth (53). However, in non-clinical samples, the CBCL-DP profile predicted non-BP psychiatric diagnoses and impairment over a 23-year follow-up (54) and was associated with anxiety and DBD over a 14-year follow-up (55). In our study, there was no difference in the Attention subscale of the CBCL was not significantly different between non-BP offspring of parents with BP and offspring of community control parents, suggesting that attention problems may not be an early risk marker for development of BP. On the other hand, the sum of the items of the CBCL-DP and the sum of the mood lability items were significantly different among the three offspring groups. The above results together with other high-risk studies (8, 9, 30, 53, 56) suggest that early symptoms of anxiety, depression, and perhaps mood lability and aggression problems may be early risk markers for BP. Prospective longitudinal follow-up of offspring of parents with BP is warranted to confirm whether these children with above-noted CBCL profiles are at higher risk to develop BP.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that, independent of DSM psychiatric disorders, offspring of parents with BP have significant dimensional psychopathology, particularly higher Total, Internalizing, and Aggression CBCL scores. This psychopathology is more severe in offspring of parents with BP who already developed bipolar spectrum disorders. However, considering that almost half of the offspring of parents with BP have not yet manifested any categorical psychiatric illness and that 90% have not developed BP (30), there is an opportunity for preventive interventions in this high-risk population. Furthermore, studies to evaluate the association of dimensional psychopathology with biological phenotypes (e.g., specific neural circuits) as well as genetic polymorphisms in predicting future BP diagnosis are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by grant #MH60952 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIMH or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors thank the families and their children who participated in this study. We also thank Carol Kostek, Wonho Ha, Ph.D., and Mary Kay Gill, M.S.N. for their assistance with manuscript preparation; the University Center for Social and Urban Research staff, the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study interviewers (Ryan Brown, Nick Curcio, Ronna Currie, Gail Oterson, Elizabeth Picard, and Lindsay Virgin), Scott Turkin, M.D., and the Dubois Regional Medical Center Behavioral Health Services staff for their collaboration. Finally, the authors thank Dr. Shelli Avenevoli and Dr. Editha Nottelmann from NIMH for their support.

Footnotes

BB has participated in forums sponsored by Forest Laboratories, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals; and has received or will receive royalties from Random House and Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. BG has received an honorarium from Purdue Pharma. DK has served on advisory boards for Pfizer, Eli Lilly & Co., Forest Pharmaceuticals, and Solvay/Wyeth Pharmaceuticals; and has served as a consultant for Servier Amerique. RSD, DA, MO, KM, MBH, TG, DS, SI, and DB do not have any commercial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Leibenluft E, Rich BA. Pediatric bipolar disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:163–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birmaher B, Axelson D. Course and outcome of bipolar spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: A review of the existing literature. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18:1023–1035. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellivier F, Golmard JL, Rietschel M, et al. Age at onset in bipolar I affective disorder: further evidence for three subgroups. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:999–1001. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perlis RH, Dennehy EB, Miklowitz DJ, et al. Retrospective age at onset of bipolar disorder and outcome during two-year follow-up: results from the STEP-BD study. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Pavuluri M. Bipolar Disorder. In: Andrés Martin MDM, Fred R, Volkmar MD, Melvin Lewis MBBS, editors. Lewis' Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook. 4th ed. London: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang K, Steiner H, Ketter T. Studies of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet. 2003;123C:26–35. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.20011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw JA, Egeland JA, Endicott J, Allen CR, Hostetter AM. A 10-year prospective study of prodromal patterns for bipolar disorder among Amish youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:1104–1111. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000177052.26476.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duffy A, Alda M, Crawford L, Milin R, Grof P. The early manifestations of bipolar disorder: a longitudinal prospective study of the offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:828–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duffy A, Alda M, Hajek T, Sherry SB, Grof P. Early stages in the development of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010;121:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein BI, Shamseddeen W, Axelson DA, et al. Clinical, demographic, and familial correlates of bipolar spectrum disorders among offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:388–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klimes-Dougan B, Ronsaville D, Wiggs EA, Martinez PE. Neuropsychological functioning in adolescent children of mothers with a history of bipolar or major depressive disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:957–965. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladouceur CD, Almeida JRC, Birmaher B, et al. Subcortical gray matter volume abnormalities in healthy bipolar offspring: potential neuroanatomical risk marker for bipolar disorder? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:532–539. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318167656e. [see comment] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips ML, Ladouceur CD, Drevets WC. A neural model of voluntary and automatic emotion regulation: implications for understanding the pathophysiology and neurodevelopment of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:833–857. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dienes KA, Chang KD, Blasey CM, Adleman NE, Steiner H. Characterization of children of bipolar parents by parent report CBCL. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:337–345. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giles LL, DelBello MP, Stanford KE, Strakowski SM. Child behavior checklist profiles of children and adolescents with and at high risk for developing bipolar disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2007;38:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wals M, Hillegers MH, Reichart CG, Ormel J, Nolen WA, Verhulst FC. Prevalence of psychopathology in children of a bipolar parent. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1094–1102. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reichart CG, Wals M, Hillegers MH, Ormel J, Nolen WA, Verhulst FC. Psychopathology in the adolescent offspring of bipolar parents. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mick E, Biederman J, Pandina G, Faraone SV. A preliminary meta-analysis of the child behavior checklist in pediatric bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youngstrom EA, Findling RL, Calabrese JR, et al. Comparing the diagnostic accuracy of six potential screening instruments for Bipolar Disorder in youths aged 5 to 17 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:847–858. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000125091.35109.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holtmann M, Goth K, Wockel L, Poustka F, Bolte S. CBCL-pediatric bipolar disorder phenotype: severe ADHD or bipolar disorder? J Neural Transm. 2008;115:155–161. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0823-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudziak JJ, Althoff RR, Derks EM, Faraone SV, Boomsma DI. Prevalence and genetic architecture of Child Behavior Checklist-juvenile bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Althoff RR, Rettew DC, Faraone SV, Boomsma DI, Hudziak JJ. Latent class analysis shows strong heritability of the child behavior checklist-juvenile bipolar phenotype. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:903–911. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volk HE, Todd RD. Does the Child Behavior Checklist juvenile bipolar disorder phenotype identify bipolar disorder? Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faraone SV, Althoff RR, Hudziak JJ, Monuteaux M, Biederman J. The CBCL predicts DSM bipolar disorder in children: a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:518–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diler RS, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, Gill M, Strober M, et al. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the CBCL-bipolar phenotype are not useful in diagnosing pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19:23–30. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doerfler LA, Connor DF, Toscano PF., Jr Aggression, ADHD symptoms, and dysphoria in children and adolescents diagnosed with bipolar disorder and ADHD. J Affect Disord. 2011;131:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayer L, Althoff R, Ivanova M, et al. Child Behavior Checklist Juvenile Bipolar Disorder (CBCL-JBD) and CBCL Posttraumatic Stress Problems (CBCL-PTSP) scales are measures of a single dysregulatory syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:1291–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holtmann M, Duketis E, Goth K, Poustka L, Boelte S. Severe affective and behavioral dysregulation in youth is associated with increased serum TSH. J Affect Disord. 2010;121:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, et al. Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:287–296. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IIIR (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial Reliability and Validity Data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollingshead AB. Four-factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University, Department of Sociology; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, et al. The family history method using diagnostic criteria. Reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34:1229–1235. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, et al. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:175–183. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, et al. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller L, Barnett S. Mood lability and bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:171–176. doi: 10.1080/09540260801889088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavuluri MN, Birmaher B, Naylor MW. Pediatric bipolar disorder: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:846–871. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000170554.23422.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luna B. Developmental changes in cognitive control through adolescence. Adv Child Dev Behav. 2009;37:233–278. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2407(09)03706-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diler RS, Uguz S, Seydaoglu G, Erol N, Avci A. Differentiating bipolar disorder in Turkish prepubertal children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:243–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Youngstrom E, Youngstrom JK, Starr M. Bipolar diagnoses in community mental health: Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist profiles and patterns of comorbidity. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angold A, Weissman MM, John K, et al. Parent and child reports of depressive symptoms in children at low and high risk of depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1987;28:901–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1987.tb00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiss E, Gentzler AM, George C, et al. Factors influencing mother-child reports of depressive symptoms and agreement among clinically referred depressed youngsters in Hungary. J Affect Disord. 2007;100:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Youngstrom E, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Patterns and correlates of agreement between parent, teacher, and male adolescent ratings of externalizing and internalizing problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:1038–1050. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Bipolar disorder during adolescence and young adulthood in a community sample. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2:281–293. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.20309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Wang PS. Prevalence, comorbidity, and service utilization for mood disorders in the United States at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:137–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, et al. Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boomsma DI, Rebollo I, Derks EM, et al. Longitudinal stability of the CBCL-juvenile bipolar disorder phenotype: A study in Dutch twins. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Biederman J, Petty CR, Monuteaux MC, et al. The child behavior checklist-pediatric bipolar disorder profile predicts a subsequent diagnosis of bipolar disorder and associated impairments in ADHD youth growing up: a longitudinal analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:732–740. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer SE, Carlson GA, Youngstrom E, et al. Long-term outcomes of youth who manifested the CBCL-Pediatric Bipolar Disorder phenotype during childhood and/or adolescence. J Affect Disord. 2009;113:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Althoff RR, Verhulst FC, Rettew DC. Adult Outcomes of Childhood Dysregulation: A 14-year Follow-up Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reichart CG, van der Ende J, Wals M, et al. The use of the GBI as predictor of bipolar disorder in a population of adolescent offspring of parents with a bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]