Abstract

Self-referencing benefits item memory, but little is known about the ways in which referencing the self affects memory for details. Experiment 1 assessed whether the effects of self-referencing operate only at the item, or general, level or also enhance memory for specific visual details of objects. Participants incidentally encoded objects by making judgments in reference to the self, a close other (one’s mother), or a familiar other (Bill Clinton). Results indicate that referencing the self or a close other enhances both specific and general memory. Experiments 2 and 3 assessed verbal memory for source in a task that relied on distinguishing between different mental operations (internal sources). Results indicate that self-referencing disproportionately enhances source memory, relative to conditions referencing other people, semantic, or perceptual information. We conclude that self-referencing not only enhances specific memory for both visual and verbal information, but can disproportionately improve memory for specific internal source details as well.

Keywords: memory, self, cognition, source, specificity

The self-reference effect, or the tendency for people to better remember information when it has been encoded in reference to the self (Rogers, Kuiper, & Kirker, 1977), has proven to be a robust encoding strategy over the past thirty years. The effect has been found under a variety of conditions, including studies in which people are instructed to remember stimuli, like personality traits, nouns, and definitions (see Symons & Johnson, 1997 for review), in people who suffer from mild depression as well as in healthy individuals (Derry & Kuiper, 1981), and across age groups, including children as young as five (Sui & Zhu, 2005) and older adults (Glisky & Marquine, 2009; Gutchess, Kensinger, & Schacter, 2010; Gutchess, Kensinger, Yoon, & Schacter, 2007; Mueller, Wonderlich, & Dugan, 1986). Although a few studies have failed to produce the self-reference effect (e.g., Bellezza & Hoyt, 1992; Keenan & Baillet, 1980; Klein & Kihlstrom, 1986; Lord, 1980), the effect occurs across the majority of self-referencing studies (Symons & Johnson, 1997).

Despite the number of findings showing that self-referencing can improve memory, little attention has been paid to understanding the mechanisms through which self-referencing influences memory. A number of processes contribute to memory, including familiarity, in which people may only have a general sense of having encountered information before, as well as recollection, in which people can re-experience aspects of the original episode with access to many details, such as what they saw or thought (Yonelinas, 2002). Research thus far on self-referencing has largely investigated the effects of self-referencing on item, or general, memory, in which only a sense of familiarity would be necessary to recognize whether something is new or old (e.g., was the word “outgoing” studied previously?). However, self-referencing also may enhance recollective processes, which would be necessary to remember specific details. Finding that self-referencing enhances both general and specific memory, as found previously for negative emotional stimuli (Kensinger, Garoff-Eaton, & Schacter, 2006, 2007), would suggest that the strategy is useful to improve the accuracy and richness of memory, particularly because memory for general, but not specific, information leaves people vulnerable to memory errors of forgetting and false recognition (Garoff, Slotnick, & Schacter, 2005). Self-referencing could be another way to enhance memory for details and reduce errors from overly general or inaccurate memory.

Thus far, research on self-referencing has been restricted in its ability to explore the specificity of memory due to the type of stimuli and tasks employed. A meta-analysis of self-reference effect research reports that approximately 80% of all studies used personality trait words (Symons & Johnson, 1997), stimuli which offer limited types of details to be encoded. The tasks performed in most self-referencing studies require participants to do a highly practiced and familiar task: relating trait words to themselves or others, or considering semantic information about the words. The memory benefit of self-referencing may therefore result from the well-practiced nature of the task and thus may not extend to nonverbal tasks. When participants are asked to read words and reference the self, there may be only a few distinct perceptual details available, such as the word’s font or color. Experience reading and speaking trains us to focus on the conceptual meaning of words; therefore the meaning of verbal stimuli will likely be considered more important and will be better remembered than the visual details. In contrast, objects like tools, clothing, electronics, and food products contain rich specific details that must be remembered or at least recognized in daily life in order to distinguish one exemplar from another. These properties of objects also allow one to assess whether specific details have been encoded into memory that can distinguish one exemplar from another, a judgment that would not be possible if the item were encoded too generally, at the item level.

There is evidence that objects can be tightly integrated with the concept of the self. Belk (1988, 1991) found that the self-concept may lie outside the body and mind in how we process and represent physical objects, like our possessions, in relation to ourselves. This extension of the self to self-relevant objects is apparent in the emphasis we place on ownership, which first emerges in young toddlers (Ross, 1996). Not only do people tend to consider owned items as extensions of the self (Belk, 1988, 1991), but they also evaluate objects randomly assigned to them in a more positive light (Beggan, 1992; Belk, 1988, 1991) and as more valuable than the same objects assigned to others, a phenomenon referred to as the endowment effect (Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, 1991). In a recent study, Cunningham, Turk, Macdonald, and Macrae (2008) found a significant memory advantage for assigned owned objects. Participants were presented with pictures of supermarket items “belonging” to themselves or to the confederate beside them. After encoding these pictures, they were asked to put their items into their own shopping basket. Participants later conducted a recognition task in which they determined whether the presented objects belonged to them or to the confederate. The superior memory for items belonging to oneself over others suggests that the self-reference effect appears not only with words but also with physical objects and that the memory advantage extends to the cognitive processes underlying ownership. Participants’ interactions with the objects by moving them had no significant impact on memory. The memory advantage therefore resulted from self-referentially encoding the owned objects, which is a very robust finding given the brief presentation and categorical similarity of the objects in this study. Based on this previous study (Cunningham, Turk, Macdonald, & Macrae, 2008), self-referential encoding appears to enhance at least general memory for both abstract concepts relevant to the self and physical objects owned by the self, although memory for specific details was not directly measured.

The present investigation probes the effects of self-referencing on general memory as well as the level of detail and specific features encoded in these memories. If self-referencing, relative to other social and semantic encoding conditions, enhances both specific and general memory, it suggests that the strategy is a beneficial technique for encoding and retrieving accurate memories that are more detailed and elaborated. If self-referential encoding does not disproportionately increase the retrieval of accurate details in memory, relative to other conditions, it suggests that encoding in reference to the self operates only by strengthening the gist, or general thematic information, of memory. In three studies, we assess the effects of self-referencing on memory for specific details associated with visual objects as well as source memory for verbal information.

EXPERIMENT 1

Method

Participants

Participants were 32 students aged 18–25. Two additional participants were removed from analyses because they misunderstood the directions for the recognition task and responded with only two of the three response options. All participants were native English speakers and none reported being colorblind. Informed consent was obtained in a method approved by the Brandeis University Institutional Review Board.

Materials

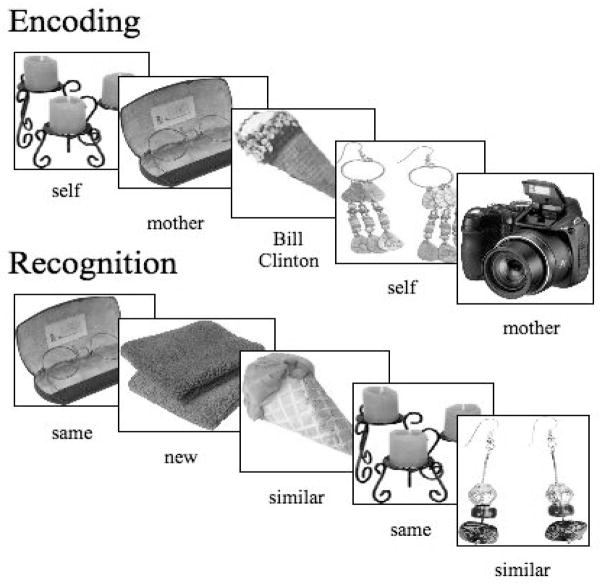

A series of 144 pairs of color photographs of familiar purchasable objects was used in this study. Each pair included two pictures of everyday, nonarousing objects with the same verbal label, for example, two bottles of water, differing in visual detail (e.g., color, size, orientation, number, shape). All objects were shown against a white background (see Figure 1). Purchasable objects were chosen in an attempt to create a realistic situation in which referencing a person might be employed and beneficial to remembering object information. Insert Figure 1

Figure 1.

Example stimuli. At encoding, objects are encoded one-third of the time by answering the question “is this an object you would buy some time in the next year?”, while participants must answer this question about their mother or Bill Clinton for the remaining two thirds. At recognition, participants indicated whether each item was the same as a studied item (same), similar to an item in encoding (similar), or new.

Encoding Procedure

The study took place over the course of two days. On the first day, participants met with the experimenter and completed the encoding task in addition to some questionnaires. Following a brief practice task with photographs of animals, participants were shown 108 of the object pictures on a computer monitor. Before viewing each object, participants saw one of three questions on the screen for 2 seconds: “is this an object you would buy sometime in the next year?”, “is this an object your mother would buy sometime in the next year?”, or “is this an object Bill Clinton would buy sometime in the next year?”. The selection of these targets was intended to contrast the self against a target with whom the participants had high personal and emotional intimacy (mother) and a target with whom participants were familiar but did not know personally (Clinton). Following the question, an object was presented for 500 msec and participants were asked to answer “yes” or “no” to the question about the specific object as quickly as possible by a key press. To regulate encoding time, the next question and object were automatically presented 1000 msec after each object’s presentation. Each participant viewed 36 objects in the self-referencing condition, 36 in the mother-referencing condition, and 36 in the Bill Clinton-referencing condition.

The order of object presentation was randomized and the condition for each object was determined through a counterbalancing scheme. Objects were divided into four lists of 36 object pairs. The same item within each pair of objects was presented to every participant during the encoding phase but each participant was only shown three out of the four object lists during encoding. Objects from the fourth list, not shown during encoding, were presented as new items during the recognition phase. For each participant, the order of the lists presented during the encoding and recognition phases followed one of eight counterbalancing orders, such that items were presented in different conditions an equal number of times across participants.

Recognition Procedure

Participants met with the experimenter two days (approximately 48 hours) after the first session. Participants first performed a practice task in which they determined whether each item was the same, similar, or new to objects studied in the practice task on Day 1. During the surprise recognition task participants were shown 54 of the same objects shown in encoding (18 from each encoding condition), 54 objects similar to items previously seen in encoding (the matched pair of the item that was not shown to the participant in the initial encoding presentation), and 36 new objects (see Figure 1 for examples). Participants saw each object for 1000 msec but the response interval was self-paced during which they pressed a key to indicate whether each object was the same, similar, or new. Participants were instructed to respond whether the object was (1) exactly the same as an object seen in the last task; (2) similar to an object previously seen, but slightly different, for example, the object could be given the same name but the details of the object (size, shape, number, etc.) differ from the original item; or (3) a completely new object. The procedure was adopted from Kensinger et al (2006; 2007). Encoding and recognition tasks were presented with E-Prime software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA). Following completion on the second day, participants were debriefed with the purpose of the study, informed of the hypotheses, thanked, and presented with the promised incentive for their participation.

Results and Discussion

Table 1 shows the proportion of objects given a same, similar, or new response, reported as a function of correct response (same, similar, or new) and condition (self, mother, Bill Clinton, new). We calculated six memory scores for each participant to assess specific and general memory for each of the three conditions (self, mother, and Bill Clinton). Specific recognition scores were calculated based on the equation used in much of the emotion and memory research (Garoff, Slotnick, & Schacter, 2005; Kensinger, Garoff-Eaton, et al., 2007; Payne, Stickgold, Swanberg, & Kensinger, 2008). The specific memory score, the proportion of correct “same” responses given to the same objects, reflects accurate memory for those exact objects studied in encoding and presented again during recognition. To examine general memory, we used the equation from Payne et al. (2008), which accounts for the fact that “similar” and “same” responses are mutually exclusive. “Similar” responses were given when participants could not remember specific details of a studied object and therefore this response type was constrained by the number of “same” responses. The general memory score was the proportion of “similar” responses given to same objects, after excluding the number of “same” responses, or specific memory. Our equation was the proportion of “similar” responses to same objects/(1 –proportion of “same” responses to same objects). As our primary concern in this study was the effect of self-and other-referencing on memory for studied (same) objects, responses to similar and new objects were of less importance and therefore not factored into the specific and general memory scores. Although a “similar” response to a similar object is a correct response, we cannot directly interpret whether this response classifies as specific or general recognition; for instance, this response could signal that a participant remembered specific details of the exact object studied during encoding and correctly identified this similar exemplar as “similar”, or this response could result from a feeling of familiarity with this object but no real memory of its details. Therefore, responses to similar objects were not factored into the memory scores. Insert Table 1.

Table 1.

Proportion of Same, Similar, and New Responses as a Function of Item Type and Condition for Experiment 1.

| Response Type | “Same” | “Similar” | “New” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self | |||

| Same | .62 (.03) | .27 (.02) | .11 (.01) |

| Similar | .14 (.02) | .46 (.02) | .40 (.02) |

| Mother | |||

| Same | .61 (.03) | .26 (.02) | .12 (.02) |

| Similar | .12 (.01) | .47 (.03) | .41 (.03) |

| Bill Clinton | |||

| Same | .55 (.04) | .25 (.02) | .19 (.02) |

| Similar | .10 (.02) | .42 (.03) | .48 (.03) |

| New | .04 (.01) | .21 (.02) | .76 (.02) |

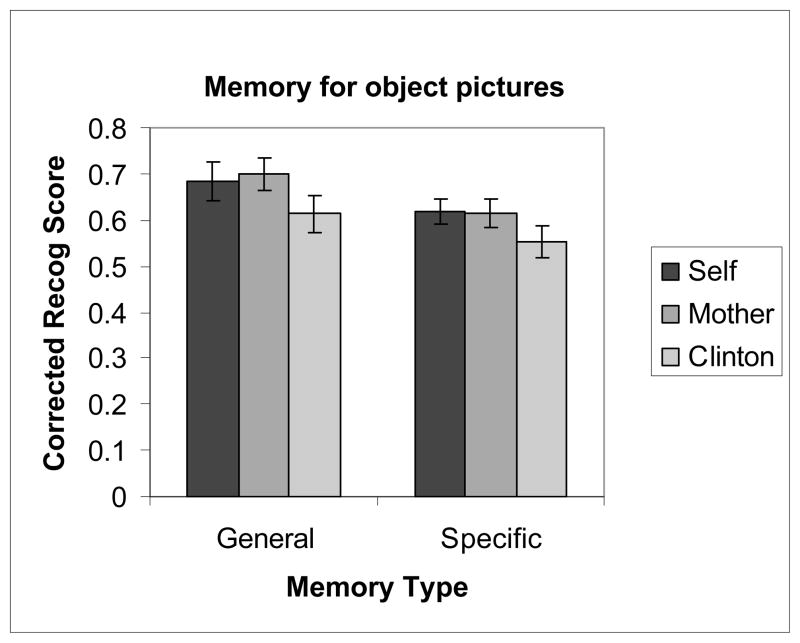

A 2 × 3 within-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare response accuracy by memory type (specific, general) and condition (self, mother, Bill Clinton). Results are displayed in Figure 2. The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of memory type, F (1, 31) = 4.21, p < .05, partial η2 = .12. Collapsing across conditions, general memory performance (M = .67) was significantly better than specific memory (M = .60). The main effect of condition also reached significance, F (2, 62) = 4.17, p < .05, partial η2 = .12. Overall, collapsing across general and specific memory, mother-referent objects (M = .66) and self-referent objects (M = .65) had higher levels of recognition than objects encoded with reference to Bill Clinton (M = .58). We conducted a series of contrasts between the levels of condition in order to clarify the nature of the condition main effect. A main effect contrast collapsing across memory type revealed that Clinton-referent objects were less likely to be remembered than objects encoded with either the self, F (1, 31) = 6.16, p < .05, partial η2 = .17, or the mother, F (1, 31) = 7.44, p < .01, partial η2 = .19. No significant differences were found in memory for self-referent and mother-referent objects, F (1, 31) = .04, p = .84, partial η2 < .01. The two-way interaction between memory type and condition did not reach significance, F (2, 62) = .12, p > .85, partial η2 < .01.

Figure 2.

Experiment 1: Recognition accuracy for specific and general memory for visual objects. Overall, general memory scores were significantly higher than specific memory scores. Self-referent and mother-referent objects were remembered significantly better than Bill Clinton-referent objects.

The examination of specific, as well as general, recognition allows us to determine that self-, and here, intimate other-referencing, improve the encoding of details in memory, rather than simply enhancing a general sense of familiarity for information . Our results suggest that self-referencing and referencing an intimate other person, like one’s mother, benefit not only memory for the “gist” of objects but also help to accurately encode some complex visual details of those objects. Across all three conditions, specific recognition scores were lower than the corresponding general memory scores but still relatively strong (above 50%), which suggests that specific details of the objects, like color, shape, and other perceptual features, were successfully encoded through these referencing techniques and later retrieved in the memory task. General memory scores reflect participants’ ability to remember the general idea of a previously seen object, for example, remembering the type of object. The lower specific and general memory scores for objects encoded in the Bill Clinton condition indicate that this encoding condition was less effective than the self or mother conditions because the details of objects in this condition were not remembered as clearly, which is consistent with the literature for self versus familiar but not intimate others (reviewed by Symons & Johnson, 1997). Encoding non-intimate others seems to produce less accurate and vivid memories than self- and intimate other-encoding. While it is somewhat surprising that self- and mother-referencing resulted in similar effects on memory, there is some precedent in the literature for this finding. We will return to this point in the discussion.

Given the disproportionate emphasis on verbal tasks in the self-referencing literature to date, our exploration of the benefits of self-referencing on memories for visually detailed objects in Experiment 1 is an important extension. Unlike trait adjectives, these objects are unlikely to be part of the pre-existing self-concept or the concept one has about their mother or Bill Clinton. However, although Experiment 1 indicates that self-referencing improves memory for specific visual details, it is unclear how this finding relates to other literature. The majority of self-referencing research focuses on memory for verbal stimuli (reviewed by Symons & Johnson, 1997), which do not contain as much rich perceptual detail as pictures do. We sought to further investigate memory for specific details in Experiment 2, using an adjective memory paradigm.

EXPERIMENT 2

In addition to the memory for visual details of an object, source information represents another type of detail in memory. Source memory describes memory for the context or conditions in which information was learned,(Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993). While there are many types of external sources to be remembered in the world, such as which person (e.g., did I learn this from my mother or my professor?) or written source (e.g., did I read this in a reputable newspaper or a tabloid?) provided information, there are also different internal sources for which the self is the source, such as whether one imagined an event occurring or told information to someone else (Johnson & Raye, 1981). Generally memories for external sources are associated with perceptual details while memories for internal sources contain details about mental operations, such as searching for relevant information, imagining, or making decisions (Johnson & Raye, 1981; Johnson, Raye, Foley, & Foley, 1981).

Accurately retrieving source information can indicate that memories have been encoded with more associated detail than memories for which source information is not available. For the typical adjective judgment paradigms used in self-referencing studies, there are few relevant external, perceptual details of sources that could be tested. In fact, perceptual judgments, such as deciding whether a word is presented in upper or lower case, typically lead to the poorest old/new recognition memory in these paradigms, compared to other typical conditions in which participants encode words by making judgments about whether an adjective described them or another person, or had a particular semantic (e.g., pleasantness) property (Symons & Johnson, 1991). These other conditions invoke judgments that rely primarily on internal sources, drawing on the memories, associations, and cognitive processes brought to bear by any given adjective judgment. For example, in order to decide, “am I clever?”, one might quickly search autobiographical memory for episodes that confirm or disconfirm this idea, draw on a general schema about one’s character, or assess the emotions this adjective evokes, in contrast to making a semantic judgment about how common or pleasant a word is, for which one might scan semantic memory in order to determine associations of the presented word. Thus, Experiment 2 further assessed the benefits of self-referencing on memory for specific details by examining source memory for verbal information. To accomplish this, participants were tested on their source memory for which task they performed at the time of encoding, with the reasoning being that each of the conditions invoked different sets of mental operations and associations.

Method

Participants

Twenty-seven students between the ages of 18 and 30 participated in the study. Informed consent was obtained in a method approved by the Brandeis University Institutional Review Board.

Materials and procedures

Participants incidentally encoded a series of adjectives by judging whether the word described them (self), was commonly encountered (common), or was presented in uppercase letters (case). These comparison conditions were selected to be consistent with previous research that employed semantic (common) as well as shallow perceptual (case) judgments in order to compare against self-referencing. Each trial consisted of a single adjective word and a cue word (self, common, or case) indicating the type of judgment to be made. Words were selected from published norms (Anderson, 1968), as used in prior studies (e.g., Gutchess, Kensinger, & Schacter, 2007). Participants made responses using keys labeled “yes” and “no” for 144 words presented for 4 seconds each. Three counterbalanced orders were used such that words were studied in each condition an equal number of times across participants. After a ten minute retention interval during which participants completed paper and pencil measures, participants received a surprise self-paced source recognition test with a single adjective presented on the screen. For 288 words, participants determined under which condition each word had been encoded, or whether it was new. Participants responded by pressing one of four buttons corresponding to “self”, “common”, “case”, or “new”.

Results and Discussion

Corrected recognition scores were calculated using hit rates minus false alarm rates to correct for guessing. Scores were calculated for both specific memory scores (i.e., correctly recalling the source) and general memory (i.e., old/new recognition). Note that different false alarm rates were used in the two analyses. Specific memory scores used a response-specific false alarm rate (e.g., misusing the label “self” for a “new” item) whereas general memory scores used an overall false alarm rate (i.e., misapplying the label corresponding to any of the three studied conditions - self, common, or case – to a “new” trial).

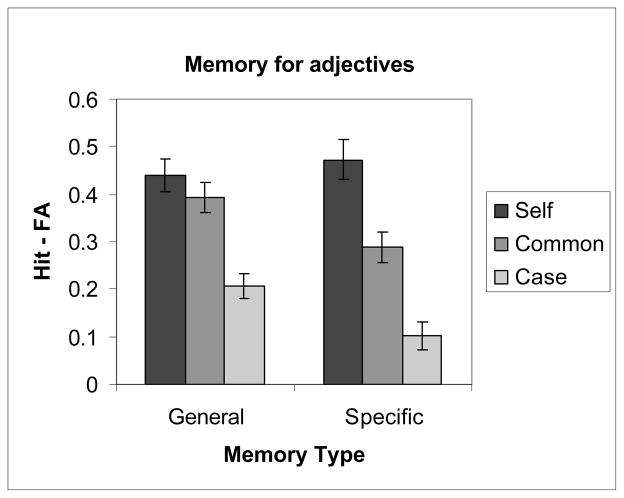

We conducted a 2×3 ANOVA with memory type (general, specific) and condition (self, common, case) as within-subjects variables. Consistent with prior studies of self-referencing (Gutchess, Kensinger, Yoon, et al., 2007; Symons & Johnson, 1997), a main effect of condition emerged, F(2, 52) = 71.55, p<.001, partial η2 = .73, with self-referencing resulting in numerically higher memory (M = .46) than judgments of commonality (M = .34) or case (M = .16). General memory (M = .35) was also superior to specific memory (M = .29), F(1, 26) = 40.65, p<.001, partial η2 = .61. Of primary importance, condition interacted with memory type, F(2, 52) = 18.65, p<.001, partial η2 = .42. Encoding source information of words in reference to the self appears to disproportionately benefit specific memory relative to the other conditions, as seen in Figure 3. Follow-up 2×2 ANOVAs using only two levels of the condition variable supported this claim, with a significant condition × memory type interaction when comparing the self trials to the common trials, F(1, 53) = 27.93, p<.001, partial η2 = .35, but no significant interaction when comparing the common trials to the case trials, p>.40.

Figure 3.

Experiment 2: Recognition accuracy for specific and general memory for verbal stimuli with semantic and perceptual comparison conditions.

The results of Experiment 2 indicate that self-referencing enhanced performance across both general and specific measures of memory, relative to semantic and shallow conditions. While this finding is consistent with prior work on general memory and the results of Experiment 1 (relative to the unfamiliar other person condition), self-referencing disproportionately benefited specific memory for source information. This enhancement indicates that a self-referencing manipulation can be particularly effective for encoding source details of verbal memories.

EXPERIMENT 3

Experiment 2 suggests that self-referencing can disproportionately benefit specific memory, which contrasts the results of Experiment 1. While we believe that this reflects the processes and features of memory that help to distinguish judgments about internal sources from each other (as opposed to highly perceptually detailed pictures of objects, as in Exp 1), the comparison conditions were also very different across the two studies. It is possible that the relatively larger boost to specific than general memory for self-referenced information in Exp 2 reflects the more semantic nature of the commonness and font case judgments, which lack the rich social content imparted by the conditions in which one makes judgments about one’s mother or Bill Clinton. Thus, we sought to extend the findings on source memory for internal judgments to conditions more comparable to those in Exp 1. Furthermore, judgments about different target individuals (rather than semantic or perceptual judgments) would require finer distinctions amongst the mental operations evoked during encoding, providing a more stringent test of the extent to which self-referencing improves the encoding of specific source details.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-four students between the ages of 18 and 27 participated in the study. Informed consent was obtained in a method approved by the Brandeis University Institutional Review Board.

Materials and procedures

The methods used in Experiment 3 were identical to those used in Experiment 2, with the exception of the judgment conditions being self-, mother- (close other), and Clinton- (familiar but not close other) referent rather than self-referent, common (semantic), and case (perceptual).

Results and Discussion

As in Experiment 2, recognition scores were calculated by subtracting false alarm rates from hit rates to account for guessing. Both specific (correctly recalling the source as self-, mother-, or Clinton-referent) and general (recalling if the word is old/new) memory scores were calculated. Different false alarm rates were used in calculating specific and general memory scores, as described in Exp. 2.

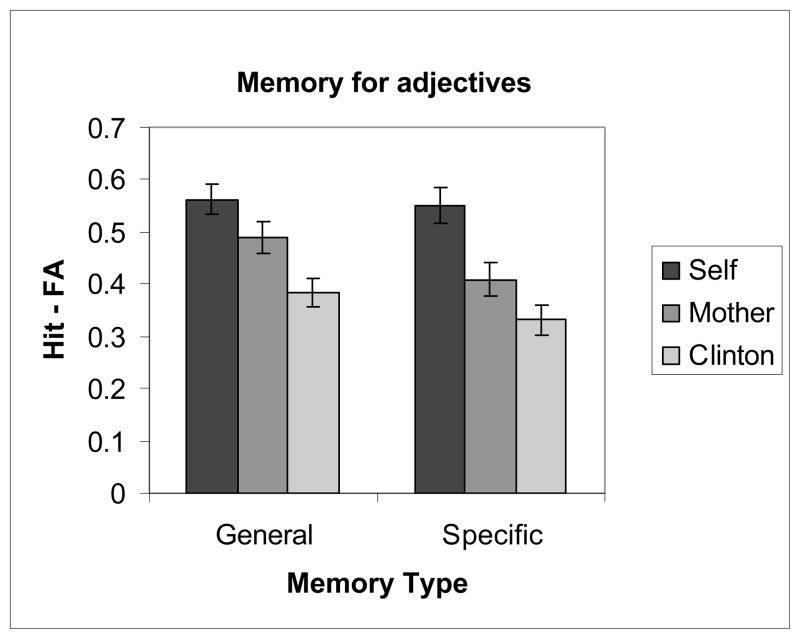

A 2×3 ANOVA with memory type (general, specific) and condition (self, mother, Clinton) as within-subject variables revealed a main effect of condition, F(2, 46) = 57.29, p<.001, partial η2 =.71. Self-referencing led to better memory performance (M = .56) than did mother- (M = .45) or Clinton-referencing (M = .36). Also consistent with the results of Exp. 1 and 2 was a main effect of memory type, F(1, 23) = 25.32, p<.001, partial η2 = .52, with general memory performance (M = .48) significantly better than specific memory performance (M = .43).

Most importantly, there was a significant interaction between condition and memory type, F(2, 46) = 4.62, p<.05, partial η2 = .17. Upon conducting subsequent 2×2 ANOVAs using two levels of the condition variable at a time (e.g., self vs. mother, mother vs. Clinton), a significant interaction was revealed in comparing self-referent trials to mother-referent trials, F(1, 23) = 9.84, p<.01, partial η2 = .30, while there was no significant interaction between mother-referent and Clinton-referent trials, p>.29.

This finding further supports our claim that self-referencing disproportionately benefits the encoding of specific details in comparison to not only semantic and perceptual encoding conditions, as found in Experiment 2, but to other-referencing conditions. These results provide evidence of the strength of self-referencing as a memory-enhancing method, especially for specific details such as the internal source of that item. Even though the paradigm employed the same conditions as Experiment 1, the disproportionate impact of self-referencing on specific memory converges with the pattern of results from Experiment 2. This finding suggests that self-referencing may be particularly potent for encoding details about mental operations, as was the case for these source memory judgments.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Across three experiments, we investigated the effect of self-referencing on memory for item details. Although the self-reference effect has proven to be fairly robust in the literature, previous studies have only provided insight into the accuracy of self-referential memories at the general, or item, level. The present studies indicate that self-referential encoding is an effective strategy to use to remember not only the “gist” of information, but also specific details such as visual properties for a highly perceptual task (Experiment 1) or the source for a task emphasizing mental operations (Experiments 2 & 3). This finding indicates that self-referencing does not operate solely through increasing familiarity or general memory for the item but also enhances memory for specific details of an event, which likely draws on more recollective processes. Such a pattern is consistent with our recent work with older adults indicating that self-referencing can enhance memory for details even for a group that tends to exhibit overly general memory (Hamami, Serbun, & Gutchess, in press).

Whereas Experiment 1 indicates a similar enhancement for general and item information when information is related to the self or to an intimately known other person, Experiment 2 and 3 find that self-referencing disproportionately increases specific memory relative to other conditions. This indicates that under some conditions, self-referencing can be a particularly effective means of encoding rich, detailed memories. We suggest that this is true for memories that rely heavily on the unique content or associations from mental operations, as is needed to distinguish different internal sources in memory (e.g., what did I think about this word? Who did I relate it to?) (Johnson & Raye, 1981; Johnson et al., 1981), but further work is necessary to characterize the contexts in which self-referencing can disproportionately enhance memory for details and qualities of events. While there have been long-standing debates as to whether self-referencing has “special” properties for memory (e.g., Rogers et al., 1977; Symons & Johnson, 1997; Gillihan & Farah, 2005; Greenwald and Banaji, 1989), an argument further bolstered by neuroimaging data indicating a distinct neural basis for self-referenced memories in contrast to other “deep” encoding conditions (e.g., Macrae, Moran, Heatherton, Banfield, & Kelley, 2004), our data argue that referencing the self can make an exceptional contribution to memory for specific details, compared to other types of judgments.

Although we postulate that the difference across the experiments in the extent of self-referencing benefit to specific memory is due to the nature of the operations required for internal source judgments (Exp 2 & 3), other factors may contribute. The difference in the findings across the studies could reflect the limited time available for encoding details. Pictures were presented for only 500 msec which, although it supported relatively robust levels of memory performance and is consistent with some prior studies (e.g., Kensinger, et al., 2006), the duration is much shorter than the 4000 msec presentation time employed in Experiments 2 & 3. The brief encoding interval may have limited participants’ ability to benefit from the encoding strategy in order to encode additional perceptual details. The relatively modest differences in the level of performance on general vs. specific memory provide support for this idea. It is also possible that performance is close to ceiling in Experiment 1, limiting our ability to detect interactions across general and specific memory. We suspect this is not the case because no participant achieved perfect recognition scores across all conditions. Furthermore, older adults, who tend to exhibit poorer memory performance, do not exhibit differential self-reference benefits across general and specific memory (Hamami et al., in press).

Another inconsistency across the studies is in the benefits of referencing a close other. While much of the literature reports a benefit for referencing the self over referencing a close, intimate other (e.g., Heatherton, et al., 2006; Klein, Burton, & Loftus, 1989; Lord, 1980), as we found in Experiment 3, there is some precedent for our Experiment 1 finding of similar benefits across these two conditions (see Bower & Gilligan, 1979; Symons & Johnson, 1997). Evidence suggests that the cognitive processes underlying self-referencing and other-referencing differ (Turk, Cunningham, & Macrae, 2008), while other research indicates that close others are integrated into the self-concept (Aron, Aron, Tudor, & Nelson, 1991). It is possible that the potentially high ecological validity of our shopping task in which people made purchase decisions could, however, minimize the distinction between self and close others. People have extensive experience shopping for intimate others, including the mother, and could sometimes even use the self as a proxy (e.g., I hate this shirt! So then would my mother.). In contrast, making trait judgments about the self vs. other may invoke highly distinct processes, which would explain the differential benefits of referencing the self vs. a close other in Experiment 3.

In conclusion, the findings of our study offer an important contribution to the self-referencing literature. Self-referencing not only enhances item memory that supports old/new decisions, but also enhances memory for perceptual details and mental operations contributing to memory for the source of information. Under some conditions, self-referencing may allow for encoding of even more specific details of memories than other encoding conditions, shown here for memories for the perceptual details of pictures of objects and source memory for judgments made about adjectives. Thus, self-referencing may be a particularly influential strategy in helping individuals to form richly detailed and accurate memories.

Figure 4.

Experiment 3: Recognition accuracy for specific and general memory for verbal stimuli with social comparison conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elizabeth Kensinger, Malcolm Watson, Xiaodong Liu, Nicole Rosa, and Amanda Hemmesch for helpful feedback and Maya Siegel, Shirley Lo, Sapir Karli, and Jessica Nusbaum for experimental assistance. Portions of this research were conducted while A.H.G. was a fellow of the American Federation for Aging Research and was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R21 AG032382).

References

- Anderson NH. Likableness Ratings of 555 Personality-Trait Words. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1968;9:272. doi: 10.1037/h0025907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron A, Aron EN, Tudor M, Nelson G. Close relationships as including other in the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Beggan JK. On the Social Nature of Nonsocial Perception - The Mere Ownership Effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Belk RW. Possessions and the Extended Self. Journal of Consumer Research. 1988;15:139–168. [Google Scholar]

- Belk RW. The Ineluctable Mysteries of Possessions. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1991;6:17–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bellezza FS, Hoyt SK. The Self-Reference Effect and Mental Cueing. Social Cognition. 1992;10:51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bower GH, Gilligan SG. Remembering Information Related to One’s Self. Journal of Research in Personality. 1979;13:420–432. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham SJ, Turk DJ, Macdonald LM, Macrae CN. Yours or mine? Ownership and memory. Consciousness and Cognition. 2008;17:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derry PA, Kuiper NA. Schematic Processing and Self-Reference in Clinical Depression. [Article] Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981;90:286–297. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.90.4.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garoff RJ, Slotnick SD, Schacter DL. The neural origins of specific and general memory: the role of the fusiform cortex. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisky EL, Marquine MJ. Semantic and self-referential processing of positive and negative trait adjectives in older adults. Memory. 2009;17:144–157. doi: 10.1080/09658210802077405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garoff RJ, Slotnick SD, Schacter DL. The neural origins of specific and general memory: The role of fusiform cortex. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillihan SJ, Farah MJ. Is self special? A critical review of evidence from experimental psychology and cognitive neuroscience. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:76–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. The self as a memory system: Powerful, but Ordinary. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hamami A, Serbun SJ, Gutchess AH. Self-referencing enhances memory specificity with age. Psychology and Aging. doi: 10.1037/a0022626. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutchess AH, Kensinger EA, Schacter DL. Aging, self-referencing, and medial prefrontal cortex. Soc Neurosci. 2007;2:117–133. doi: 10.1080/17470910701399029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutchess AH, Kensinger EA, Schacter DL. Functional neuroimaging of self-referential encoding with age. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutchess AH, Kensinger EA, Yoon C, Schacter DL. Ageing and the self-reference effect in memory. Memory. 2007;15:822–837. doi: 10.1080/09658210701701394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Wyland CL, Macrae CN, Demos KE, Denny BT, Kelley WM. Medial prefrontal activity differentiates self from close others. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2006;1:18–25. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Hashtroudi S, Lindsay DS. Source Monitoring. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:3–28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Raye CL. Reality monitoring. Psychological Review. 1981;88:67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Raye CL, Foley HJ, Foley MA. Cognitive operations and decision bias in reality monitoring. American Journal of Psychology. 1981;94:37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Knetsch JL, Thaler RH. Anomalies - The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status-Quo Bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1991;5:193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan JM, Baillet SD. Memory for personally and socially significant events. Memory for personally and socially significant events 1980 [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Garoff-Eaton RJ, Schacter DL. Memory for specific visual details can be enhanced by negative arousing content. Journal of Memory and Language. 2006;54:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Garoff-Eaton RJ, Schacter DL. Effects of emotion on memory specificity in young and older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62:208–215. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.p208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Schacter DL. Amygdala activity is associated with the successful encoding of item, but not source, information for positive and negative stimuli. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2564–2570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5241-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Burton HA, Loftus J. Two Self-Reference Effects - The Importance of Distinguishing between Self-Descriptiveness Judgements and Autobiographical Retrieval in Self-Referent Encoding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:853–865. [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Kihlstrom JF. Elaboration, Organization, and the Self-Reference Effect in Memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General. 1986;115:26–38. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.115.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord CG. Schemas and Images as Memory Aids - Two Modes of Processing Social Information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:257–269. [Google Scholar]

- Macrae CN, Moran JM, Heatherton TF, Banfield JF, Kelley WM. Medial prefrontal activity predicts memory for self. Cerebral Cortex. 2004;14:647–654. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller JH, Wonderlich S, Dugan K. Self-referent processing of age-specific material. Psychol Aging. 1986;1:293–299. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.1.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne JD, Stickgold R, Swanberg K, Kensinger EA. Sleep preferentially enhances memory for emotional components of scenes. Psychological Science. 2008;19:781–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TB, Kuiper NA, Kirker WS. Self-reference and the encoding of personal information. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1977;35:677–688. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.35.9.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HS. Negotiating principles of entitlement in sibling property disputes (vol 32, pg 90, 1996). [Correction, Addition] Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:560–560. [Google Scholar]

- Sui J, Zhu Y. Five-year-olds can show the self-reference advantage. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:382–387. [Google Scholar]

- Symons CS, Johnson BT. The self-reference effect in memory: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:371–394. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk DJ, Cunningham SJ, Macrae CN. Self-memory biases in explicit and incidental encoding of trait adjectives. Consciousness and Cognition. 2008;17:1040–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonelinas AP. The nature of recollection and familiarity: A review of 30 years of research. Journal of Memory and Language. 2002;46:441–517. [Google Scholar]