Abstract

Blimp-1 is a transcriptional repressor that promotes the differentiation of CD8+ T cells into short-lived KLRG-1+ effector cells (SLEC), but how it operates remains poorly defined. Here we show that Blimp-1 binds and represses the Id3 promoter in SLEC. Repression of Id3 by Blimp-1 was dispensable for SLEC development but limited their capacity to persist as memory cells. Enforced expression of Id3 was sufficient to rescue SLEC survival and enhanced recall responses. Id3 function was mediated in part through inhibition of E2a transcriptional activity and induction of genes regulating genome stability. These findings identify a Blimp-1-Id3-E2a axis as a key molecular switch that determines whether effector CD8+ T cells are programmed to die or enter the memory pool.

B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp-1) is a transcriptional repressor encoded by PR domain containing 1, with ZNF domain (Prdm1) that was originally described to program the differentiation of B cells into end-stage, immunoglobulin secreting plasma cells1. Blimp-1 has now emerged as a key master regulator of terminal differentiation in a variety of cell types including keratinocytes, osteoclasts as well as T lymphocytes2-4. In CD8+ T cells, Blimp-1 is required for differentiation into perforin+, granzyme B+, cytolytic effector T cells and is necessary for efficient viral infection clearance5-7. Higher levels of Blimp-1 are observed in short-lived effector CD8+ T cells expressing killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 (KLRG-1) (SLEC) compared to KLRG-1−IL-7R+ memory precursor cells (MPEC)6-9. In the absence of Blimp-1, CD8+ T cells predominantly develop into MPEC resulting in increased formation of long-lived CD62L+, IL-2 releasing, central memory T cells (TCM)5-7.

Although it is clear that Blimp-1 can inhibit CD8+ T cell memory formation by driving T cells to senescence5-7, 10, 11, the molecular mechanisms downstream of Blimp-1 remain poorly defined. Currently, only a few genes have been characterized as direct targets of Blimp-1 in T cells, including B cell lymphoma 6 (Bcl6), Il2 and Fos, which have been implicated in the homeostasis and long-term persistence of CD8+ T cells12-14.

Here we show that Blimp-1, similar to what is observed in B cells15, directly binds the promoter of the DNA binding inhibitor Id3, an antagonist of E protein transcription factors, and represses its expression in effector CD8+ T lymphocytes. Repression of Id3 by Blimp-1 enhanced E2a transcriptional activity and was a critical determinant of whether effector CD8+ T cells were destined to die or enter into the memory pool.

Results

Blimp-1 represses Id3 expression in effector-T cells

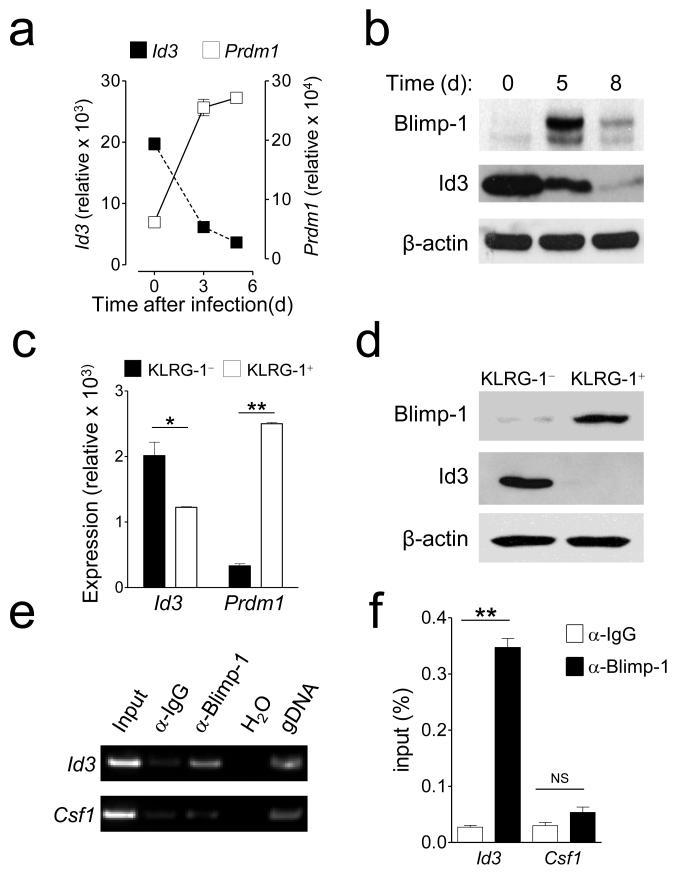

Transcriptome analysis of effector CD8+ T cell subsets has revealed Id3 as the most upregulated transcription factor in MPEC compared to SLEC6. Furthermore, Id3 was also highly expressed in effector CD8+ T cells lacking Blimp-1 compared to wild type (WT) cells6. We sought to further investigate the relationship between Blimp-1 and Id3 in CD8+ T cells by evaluating their expression levels during immune responses to a viral infection. We adoptively transferred pmel-1 CD8+ T cells, which recognize the shared melanoma-melanocyte differentiation antigen gp10016, and evaluated the expression of Prdm1 and Id3 following infection with a recombinant strain of vaccinia virus encoding the cognate antigen gp100 (gp100-VV). Prdm1 expression was low in naïve T cells and progressively increased with time after infection and inversely related to Id3 expression (Fig. 1a). Similarly, Blimp-1 and Id3 proteins were reciprocally expressed in naïve and activated CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1b). We observed in late effector T cells a reduction in Blimp-1 that was not paralleled by an increase of Id3, indicating that once repressed, Id3 expression cannot be regained by the sole removal of Blimp-1 (Fig. 1b). We further confirmed that Prdm1 mRNA is highly expressed in ex vivo isolated SLEC while Id3 is enriched in MPEC (Fig. 1c). The same expression pattern was observed for Blimp-1 and Id3 proteins (Fig. 1d). These findings indicate that Blimp-1 and Id3 are inversely regulated and suggest that Blimp-1 might directly repress Id3 expression.

Figure 1. Blimp-1 binds the Id3 promoter and represses its expression in effector CD8+ T cells.

(a) mRNA expression levels of Prdm1 and Id3 in naïve or adoptive transferred pmel-1 CD8+ T cells at indicated time-points after gp100-vaccinia virus infection. Values are obtained with qRT-PCR and normalized to Actb mRNA levels. (b) Protein expression levels of Blimp-1 and Id3 of naïve and activated CD8+ T cells at indicated time-points after stimulation with anti-CD3, anti-CD28 and IL-2. (c) Relative expression levels of Prdm1 and Id3 in KLRG-1+ and KLRG-1− pmel-1 CD8+ T cells 5 days after infection. Values are obtained with qRT-PCR and normalized to Actb mRNA levels. (d) Protein expression levels of Blimp-1 and Id3 in KLRG-1+ and KLRG-1− pmel-1 CD8+ T cells 5 days after infection. (e) Amplification of Id3 and Csf1 promoter region from anti-Blimp-1 antibody immunoprecipitated chromatin samples. Input DNA was amplified with the same primers as a control for the equivalence of the starting material. Anti-IgG antibody was used as a non-specific control. (f) Amplification of Id3 promoter region from either anti-IgG or anti-Blimp-1 antibody immunoprecipitated chromatin samples measured by quantitative ChIP-PCR. Csf1 was used as a non-specific control. Data are representative of 2 (a, c-f) or 4 (b) independent experiments (error bars (a, c, f), s.e.m. of 3 samples). * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.001.

The promoter region of Id3 contains four consensus AGGGAAAGGG Blimp-1-binding sites and has been shown to be a direct target of Blimp-1 in a human B cell line6, 15. To test whether Blimp-1 directly binds the Id3 promoter in CD8+ T cells, we immunoprecipitated Blimp-1-DNA complexes in effector T cells and amplified the DNA with primers specific for the promoter region of Id3 or colony stimulating factor 1 (Csf1), which is not targeted by Blimp-115. We found that Id3 but not Csf1 was specifically precipitated in effector T cells (Fig. 1e). These results were further validated by quantitative ChIP-PCR which revealed a significant enrichment of Blimp-1 within the Id3 but not the Csf1 promoter region (Fig. 1f). Taken together, these findings indicate that Id3 is directly targeted and repressed by Blimp-1 in effector CD8+ T lymphocytes.

Id3 is essential for CD8+ memory T cell formation

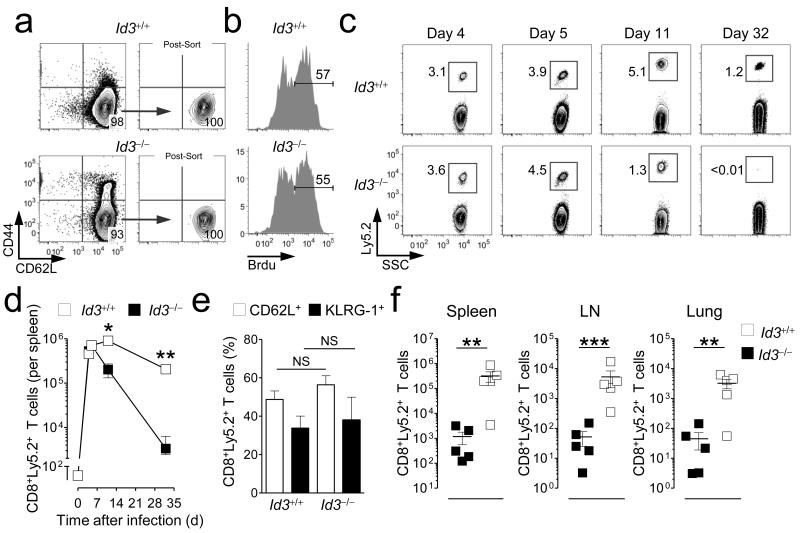

The function of Id3 has been extensively characterized in thymocyte development17 but its role in mature T cells has only just begun to be addressed18. Id3−/− mice have defective thymocyte development due to impairment in positive and negative selection17, thereby inexorably compromising the mature T cell compartment19. Consistent with previous observations19, we found that Id3−/− CD8+ T cells from WT as well as from pmel-1 mice displayed an activated phenotype characterized by the upregulation of CD44 and downregulation of CD62L (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The memory-like phenotype of Id3−/−CD8+ T cells might be dependent on IL-4 released by a dysregulated Id3−/− NKT cell population19 as well as the combined effects of homeostatic proliferation and possible expansion of auto-reactive clonotype populations that were not deleted during negative selection (Supplementary Fig. 1b,c). Indeed, the pmel-1 Id3−/− T cell phenotype could be completely rescued by removal of Id3−/− NKT cells, endogenous T cell receptor (TCR) α and β chains and normalization of T cell homeostasis in pmel-1 Rag1−/− and pmel-1 Rag1−/− Id3−/− mixed bone marrow chimera in WT hosts (Supplementary Fig. 1d,e). Thus, to study the role of Id3 in a CD8+ T cell immune response, we employed CD44−CD62L+ naïve CD8+ cells isolated from pmel-1 Rag1−/− Id3−/− mice (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Id3 is essential for the generation of CD8+ memory T cells.

(a) Representative flow cytometry analysis of pmel-1 Rag1−/− Id3+/+ CD8+ T cell and pmel-1 Rag1−/− Id3−/− CD8+ T cells before and after sorting CD62L+CD44− naïve CD8+ T cells. Contour plots are shown after gating on CD8+ cells. (b) Representative flow cytometry analysis of BrdU+ incorporation 4 days following adoptive transfer of Id3+/+ or Id3−/− pmel-1 Rag1−/−CD8+ T cells in conjunction with gp100-VV infection. Infected mice received 1.5 mg BrdU 16 hours before analysis of splenocytes. (c,d) Representative flow cytometry analysis (c) and numbers (d) of Ly5.2+ CD8+ pmel-1 T cells following adoptive transfer of 6 × 103 Id3+/+ or Id3−/− pmel-1 Rag1−/−CD8+ T cell at indicated time-points after gp100-VV infection. Contour plots show Ly5.2+ T cells after gating on CD8+ cells. (e) Percentage of CD62L+ and KLRG-1+ pmel-1 Rag1−/−CD8+ T cells in Id3−/− or Id3+/+ groups 6 days after transferring Id3+/+ or Id3−/− pmel-1 Rag1−/−CD8+ T cells in conjunction with gp100-VV infection. (f) Numbers of CD8+ Ly5.2+ pmel-1 T cells in the spleen, lymph node, and lung following adoptive transfer of 4 × 104 Id3+/+ or Id3−/− pmel-1 Rag1−/− CD8+ T cell at day 30 after gp100-VV infection. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (error bars (d, e), s.e.m. of 3-4 samples). * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001.

In other organ systems, Id3 has been shown to regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival depending on the cell type20. We therefore measured T cell expansion, differentiation and long-term persistence of adoptively transferred naïve pmel-1 Rag1−/− Id3−/− T cells compared with naïve pmel-1 Rag1−/− Id3+/+T cells following gp100-VV infection. To evaluate T cell proliferation, we injected BrdU 16 hours before analyzing uptake in splenocytes. Id3-deficient pmel-1 T cells proliferated similarly to control cells (58% ±s.e.m. 2.7 Brdu+ Id3−/− T cells vs 61% ± s.e.m. 2.7 Brdu+ Id3+/+ T cells and Fig. 2b), and both populations expanded almost 100-fold in the spleen at the peak of the immune response 5 days after infection (Fig. 2c,d), indicating that in mature CD8+T cells, Id3 is dispensable for competent cell proliferation. Furthermore, we found no difference in the relative composition of effector T cell subsets as measured by the expression of CD62L and KLRG-1 (Fig. 2e), underscoring that Id3 also does not control T cell differentiation in response to antigenic stimulation. However, there was a significant difference in survival of the effector T cell population, which profoundly contracted in the absence of Id3 and failed to form physiological numbers of memory T cells (Fig. 2c,d and Supplementary Fig. 2). These results were not due to differences in organ tropism, because we found fewer numbers of Id3−/− CD8+ memory T cells in both lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues (Fig. 2f). By contrast, Id3, which is highly expressed in naïve T cells, was dispensable for their long-term survival (Supplementary Fig. 3). These findings indicate that Id3 is essential for CD8+ memory T cell formation and suggest that down-regulation of Id3 by Blimp-1 is a programmed switch that controls the survival of effector T cell-populations and their maturation into long-lived memory T cells.

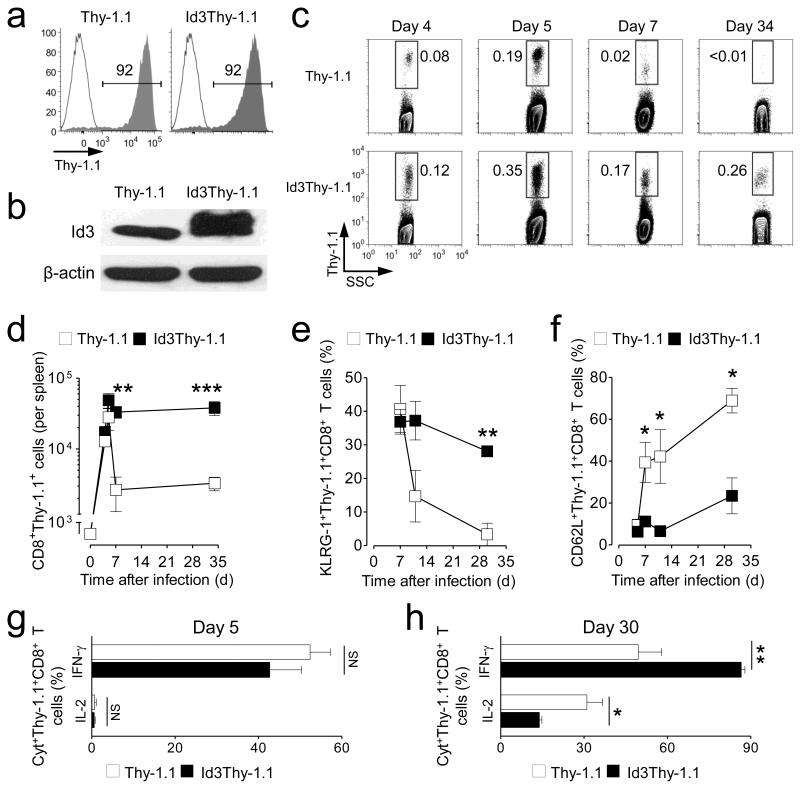

Enforced expression of Id3 promotes SLEC persistence

Given the results described above, we hypothesized that Blimp-1 limits the long-term survival of effector T cells by repressing Id3 transcription. We therefore sought to determine whether constitutive expression of Id3 could enhance the generation of memory CD8+ T cells. Pmel-1 CD8+ T cells were transduced with a multicistronic 2A peptide-based retrovirus21 encoding V5-tagged Id3 and Thy-1.1 (Id3Thy-1.1) or Thy-1.1 alone (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Expression of Thy-1.1 indicated a similarly high transduction efficiency of the two constructs (Fig. 3a). V5-tagged Id3 could be detected by Id3-specific antibody immunoblotting as a slightly slower migrating band compared to endogenous Id3 protein (Fig. 3b) or by V5-specific antibody (Supplementary Fig. 4b). We evaluated the proliferative response and persistence of adoptively transferred Id3Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells upon gp100-VV infection. No differences in phenotype or function were observed in transduced cells prior to transfer (Supplementary Fig. 5). Proliferation of Id3 overexpressing CD8+ T cells was comparable to control cells, indicating that enforced expression of Id3 did not significantly impact the proliferative capacities of developing effector T cells (Fig. 3c,d). However, we observed a striking difference in long-term T cell survival between these two groups. While about 90% of control CD8+ T cells underwent physiological contraction following the peak of the effector response, large numbers of Id3Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells persisted (Supplementary Fig. 6), resulting in a 10-fold relative increase of persisting memory T cells in the spleen (Fig. 3c,d). Thus, experiments using gain- and loss-of-function led to the same conclusion that Id3 is a key regulator of CD8+ T cell memory formation.

Figure 3. Enforced expression of Id3 promotes long-term survival of KLRG-1+ effector T cells.

(a) Percentage of Thy-1.1 positive cells in pmel-1 CD8+ T cells transduced with retrovirus expressing Id3 and Thy-1.1 (Id3Thy-1.1) or Thy-1.1 alone. (b) Id3 protein expression levels in Id3Thy-1.1 or Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells by anti-Id3 immunoblotting. (c) Representative flow cytometry analysis of splenic T cells following adoptive transfer of 6 × 102 Id3Thy-1.1 or Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells at indicated time-points post gp100-VV infection. Contour plots show Thy-1.1+ T cells after gating on CD8+ cells. (d-f) Numbers of (d), percentage of KLRG-1+(e) and percentage of CD62L+ (f) pmel-1 Thy-1.1+ CD8+ T cells in the spleen following adoptive transfer of Id3Thy-1.1 or Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells in conjunction with gp100-VV infection. (g,h) Percentage of pmel-1 Thy-1.1+ CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ and IL-2 after stimulation with leukocyte activation cocktail at day 5 (g) and day 30 (h) post infection. Data are representative of 2 (g, h), 3 (b, e, f), or 5 (a, c, d) independent experiments (error bars (d-h), s.e.m. of 3-4 samples). * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001.

Prdm1−/−CD8+ T cells display high levels of Id3 and preferentially formed MPEC over SLEC resulting in increased numbers of memory T cells5-7. We therefore hypothesized that Id3 overexpression would mimic Blimp-1 deficiency and enrich for MPEC. Contrary to our assumption, we found no differences in the frequency of KLRG-1+ or CD62L+ CD8+ T cells between Id3 overexpressing CD8+ T cells and controls at the peak of the effector response (Fig. 3e,f). Furthermore, intracellular cytokine staining revealed similar interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IL-2 secretion profiles five days after infection, indicating that effector T cells generated under the constitutive expression of Id3 were also functionally comparable to control cells (Fig. 3g). However, while the vast majority of SLEC in the control group underwent apoptosis after the peak of the immune response and continued to decline, Id3 overexpressing KLRG-1+ T cells persisted at high levels over time (Fig. 3e). This differential survival capacity of Id3Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells compared to controls resulted in an enrichment of effector memory cells (TEM) one month after infection as manifested by the low percentage of CD62L+ (Fig. 3f) and IL-2 producing T cells at this time-point (Fig. 3h).

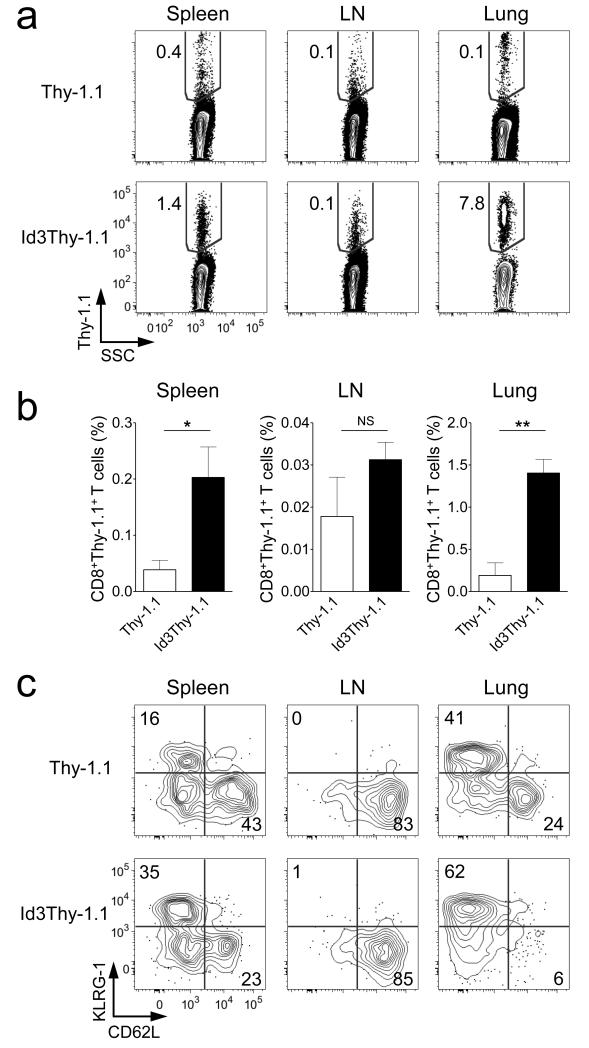

Because enforced expression of Id3 prevented contraction of the SLEC population enhancing the accumulation of TEM, we reasoned that Id3 overexpressing memory T cells might be further enriched in peripheral tissues relative to lymph nodes, which are niches for TCM cells. Consistent with our hypothesis, we observed significantly higher frequencies of Id3Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells in the lung but not in the lymph node compared to control cells as result of preferential accrual of CD62L−KLRG-1+ cells in the periphery (Fig. 4a-c). Taken together, these results reveal that Id3 alone is sufficient to rescue SLEC from apoptosis and indicate that Blimp-1, which is highly expressed in KLRG-1+ T cells, controls their survival by regulating Id3 expression levels.

Figure 4. CD8+ T cells overexpressing Id3 are enriched in peripheral tissues.

(a) Representative flow cytometry analysis of T cells from spleen, lymph node, and lung following adoptive transfer of 3 × 105 Id3Thy-1.1 or Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells 40 days post gp100-VV infection. Contour plots show Thy-1.1+ T cells after gating on CD8+ cells. (b) Percentage of pmel-1 CD8+ Thy-1.1+ T cells in the spleen, lymph node, and lung as described in a. (c) Representative flow cytometry analysis of pmel-1 CD8+ Thy-1.1+ T cells from spleen, lymph node, and lung. Contour plots show KLRG-1 and CD62L expression after gating on CD8+ Thy-1.1+ cells. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (error bars (b), s.e.m. of 3 samples). * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01.

Ectopic expression of Id3 enhances recall responses

A key attribute of memory T cells is the ability to proliferate and differentiate into large numbers of effector T cells in response to a secondary antigenic challenge. We therefore sought to determine whether the increased pool of memory CD8+ T cells generated under constitutive expression of Id3 would result in superior recall responses. Thirty days after adoptive transfer of Id3 overexpressing CD8+ T cells and gp100-VV infection, we challenged the hosts with a heterologous fowlpox virus encoding gp100 and evaluated T cell expansion and secondary memory formation. We observed a 3-fold increase in pmel-1 CD8+ T cells at the peak of the secondary effector phase in mice that received Id3 overexpressing T cells (Fig. 5a,b). Despite these relatively small differences in the magnitude of the effector response, we again observed a survival advantage for Id3 overexpressing effector T cells leading to a greater number of secondary memory T cells, although these differences were not as pronounced as we observed in primary responses (Fig. 5a,b). These results indicate that Id3 is sufficient to rescue the survival but not the proliferative capacity of SLEC.

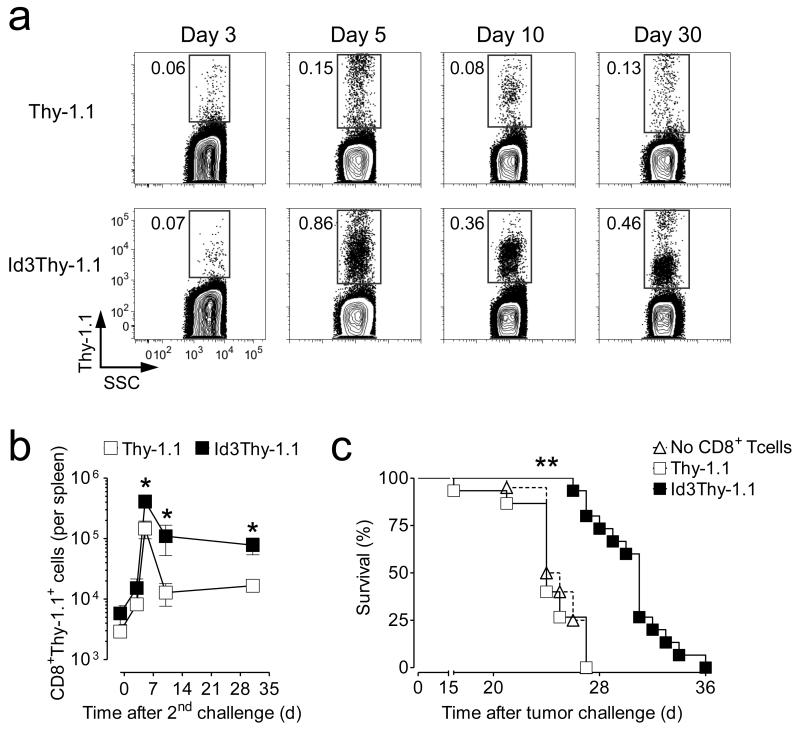

Figure 5. CD8+ T cells overexpressing Id3 mediated enhanced secondary responses.

(a) Representative flow cytometry analysis of splenic T cells following adoptive transfer of 6 × 102 Id3Thy-1.1 or Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells together with gp100 vaccinia virus and rechallenged with gp100 fowlpox virus 30 days after the primary infection. Contour plots show Thy-1.1+ T cells after gating on CD8+ cells. (b) Numbers of pmel-1 Thy-1.1+ CD8+ T cells in the spleen following secondary gp100-viral challenge as described in a. (c) Survival of WT mice challenged with 105 B16 melanoma cells 30 days after gp100-VV infection with or without adoptive transfer of Id3Thy-1.1 or Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells. Data are representative (a, b) or pooled (c) of 2 independent experiments (error bars (b, c), s.e.m. of 3-7 samples).* = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.001.

To determine whether memory CD8+ T cells generated under constitutive expression of Id3 would confer increased protection, we tested their ability to reject the challenge of gp100+ B16 melanoma. B16 melanoma cells are poorly immunogenic as manifested by the inability of pmel-1 TCR transgenic mice to delay tumor growth compared with non transgenic controls16. Addition of Thy-1.1-transduced pmel-1 memory CD8+ T cells did not improve the survival of tumor-challenged mice compared with mice that received gp100-VV infection alone (Fig. 5c). By sharp contrast, transfer of pmel-1 memory T cells constitutively expressing Id3significantly enhanced the survival of mice challenged with B16 (Fig. 5c). Altogether, these findings indicate that Id3 overexpression improves secondary memory responses by increasing the absolute numbers of TEM.

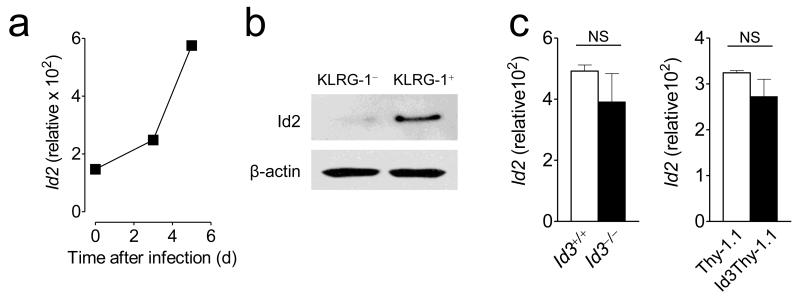

Id3 induces memory T cell formation independently of Id2

The Id family member Id2 has been reported to affect the magnitude of CD8+ effector responses and consequently the generation of long-lived memory T cells22. In contrast with Id3, which is progressively downregulated in differentiating effector T cells, Id2 mRNA levels increased reaching maximal expression at the peak of the effector response (Fig. 1a and Fig. 6a)22. In addition, we found that Id2 and Id3 had also a reciprocal expression pattern in effector T cell subsets with an enrichment of Id2 protein in SLEC and Id3 in MPEC (Fig. 1c,d and Fig. 6b). To determine whether Id2 expression is affected by Id3, we examined the Id2 transcripts in effector cells lacking or overexpressing Id3 compared to control cells. Neither deletion nor enforced expression of Id3 altered Id2 levels in effector cells (Fig. 6c), a result consistent with the finding that Id2 expression is similar in Id3−/− and Id3+/+ splenocytes as assessed by Northern blot23. These results indicate that Id2 is not redundant to Id3 nor contributes to Id3’s function as a regulator of CD8+ T cell memory.

Figure 6. Id3 does not affect Id2 expression in effector CD8+ T cells.

(a) mRNA expression levels of Id2 in naïve or adoptively transferred pmel-1 CD8+ T cells at indicated time-points after gp100-VV infection. (b) Protein expression levels of Id2 in KLRG-1+ and KLRG-1− pmel-1 CD8+ T cells 5 days after infection. (c) mRNA expression levels of Id2 in adoptively transferred Id3+/+ and Id3−/− (left panel) or Id3Thy-1.1 and Thy-1.1 (right panel) pmel-1 CD8+ T cells 5 days after gp100-VV infection. Values are obtained with qRT-PCR and normalized to Actb mRNA levels. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (error bars (a, c), s.e.m. of triplicates).

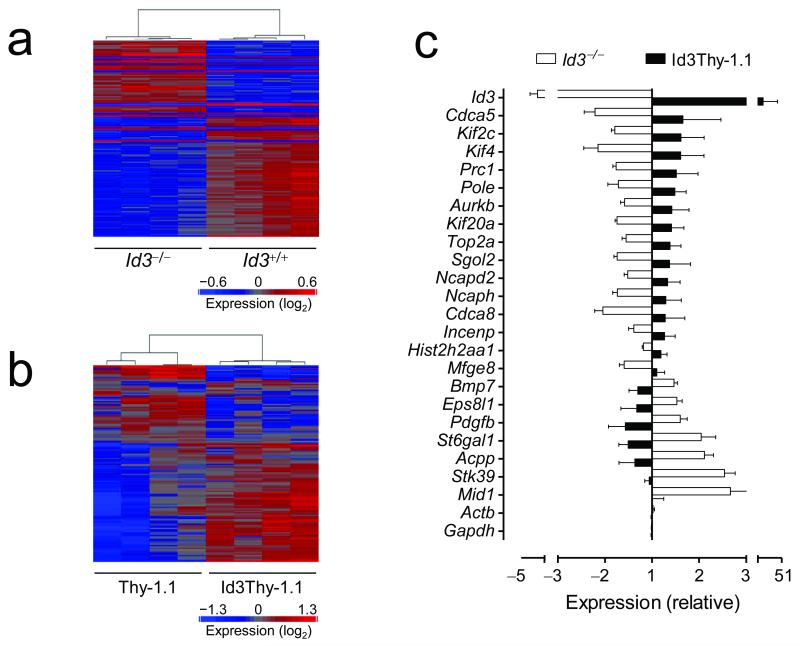

Id3 induces genes regulating DNA-replication and repair

To better understand the mechanisms by which Id3 regulates CD8+ T cell survival and memory formation, we compared the transcriptomes of Id3−/− and Id3+/+ CD8+ T cells as well as Thy-1.1 and Id3Thy-1.1 CD8+ T cells sorted ex vivo 5 days post infection in subsequent experiments (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 1). We found 138 genes affected by the gain or loss of function of Id3 (>1.3 fold change in expression and false discovery rate P < 0.05) (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 1). To accurately assess the amount of functional Id3, Id3 probe-sets specific for transcript segments other than those affected by transgenic manipulation were excluded from the analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7). Id3 was the gene most significantly affected, with a 3.8 fold decrease in Id3−/− CD8+ T cells (P = 9.3 × 10−9) and a 42.9 fold increase in Id3Thy-1.1 CD8+ T cells relative to controls (P = 5.6 × 10−14), confirming the integrity of these assays. We observed strikingly similar transcriptional differences between Id3−/− versus Id3+/+ and Thy-1.1 versus Id3Thy-1.1 T cells as manifested by the expression pattern of their heat maps (Fig. 7a,b). About one third of the genes were involved in DNA replication and repair (Supplementary Table 1), many of which could be visualized in a defined network (Supplementary Fig. 8). Virtually all genes regulating DNA replication and repair were reciprocally modulated by Id3 manipulation, such that genes downregulated in Id3−/− T cells were induced by Id3 overexpression and vice versa (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Table 1). These genes included Minichromosome maintenance complex component (Mcm) 2, 3, and 10, and Topoisomerase (DNA) II alpha (Top2a), Kinesin family members (Kif) 2c, 4a, 14 and 20a, Cell division cycle associated (Cdca) 5 and 8, Forkhead box M1 (Foxm1), and NIMA-related kinase 2 (Nek2), which are either ‘caretakers’ essential to maintain genome integrity during cell division or play crucial roles in insuring proper chromosome segregation during mitosis and fidelity of the cell division process24-31. Dysregulation of these molecules results in serious aberrancies during mitosis, such as chromosome missegregation, cytokinesis defects and overt aneuploidy which can trigger apoptosis32. Serine threonine kinase 39 (Stk39), which mediates apoptosis following genotoxic stress33 was down regulated by Id3, further underscoring the importance of Id3 in regulating genes essential for genome integrity.

Figure 7. Id3 modulates the expression of genes involved in DNA replication and repair.

(a,b) Heat maps of differentially expressed genes (>1.3 fold change in expression and false discovery rate P < 0.05) between Id3+/+ and Id3−/− (a) or Id3Thy-1.1 and Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells (b) sorted 5 days after gp100-VV infection. Data represent 2 separate experiments (upper and lower panels) in which groups were analyzed in biological quadruplicates. (c) Fold changes of genes involved in DNA replication and repair network differentially expressed in Id3−/− and Id3Thy-1.1 relative to controls.

It is noteworthy that the pro- and anti-apoptotic factors implicated in the Id2-mediated survival of effector T cells, including B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade B, member 9 (Serpinb9) and BCL2-like 11 (Bcl2l11), were not influenced by Id3 gain or loss of function (<1.3 fold change in expression and false discovery rate P > 0.05) with the exception of Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (Ctla4)22. These findings indicated that the mechanisms underlying the pro-survival effect of Id3 and Id2 are distinct. While Id2 relies upon the induction of prototypical anti-apoptotic factors, Id3 promotes survival of CD8+ effector T cells through the coordinated expression of key regulators for genomic stability.

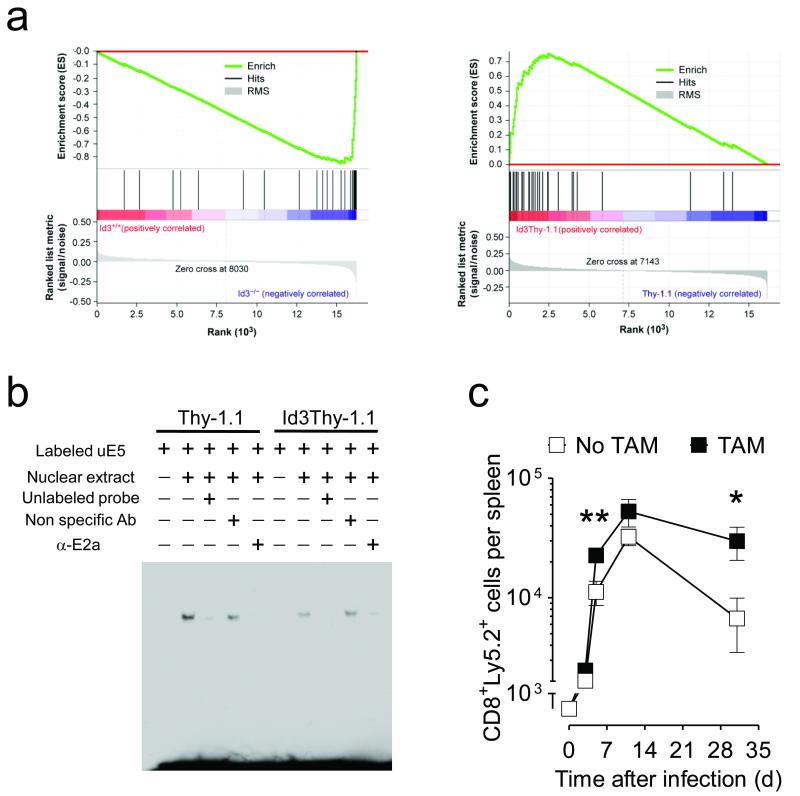

Deletion of Tcf3 enhances CD8+ T cell memory formation

In order to further explore the mechanism behind Id3 mediated enhancement of CD8+ survival and memory formation, we performed a Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) using our microarray data against the C2 curated gene sets in the GSEA database. Notably, a gene set representing transcriptional differences in pre-B-cell lines deficient of Transcription factor 3 (Tcf3), which encodes the E protein E2a, was substantially absent in Id3−/− CD8+ T cells whereas a positive enrichment was observed in Id3Thy-1.1 CD8+ T cells compared to controls (Fig. 8a and Supplementary Fig. 9)34, 35. Id proteins prevent E proteins from binding to the promoter of target genes by forming heterodimers through helix-loop-helix domains to either repress or activate gene transcription depending on the cellular context17, 36, 37. The fact that genes highly expressed in Tcf3 deficient cells were also enriched in T cells with higher content of Id3 suggested that Id3 might in part act through inhibition of E2a transcriptional activity in mature CD8+ T cells. To test whether overexpression of Id3 would impair the DNA-binding capacity of E2a in mature T cells, we tested the ability of nuclear extract from Id3Thy-1.1 effector T cells to interact with oligonucleotides containing the consensus E-box sequence in an Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA). We found that the intensity of the E protein-DNA binding band was significantly reduced in T cells constitutively expressing Id3 compared to controls and attenuated by an E2a specific antibody (Fig. 8b), indicating that Id3 antagonizes E2a binding to DNA in CD8+ effector T cells.

Figure 8. Deletion of E2a increases CD8+ memory T cell formation.

(a) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of overexpressed genes in pre-B-cell lines deficient of Tcf3 compared to transcriptomes of Id3−/− and Id3+/+ (left panel) or Id3Thy-1.1 and Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells (right panel) sorted 5 days after gp100-VV infection. Data represent 2 separate experiments (left and right panels) in which groups were analyzed in biological quadruplicates. (b) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of nuclear extract from Id3Thy-1.1 or Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells using biotin-labeled oligonucleotide probes containing the E-box binding sites. Unlabeled oligonucleotide probes were used as competitors. Anti-E2a antibody and non-specific antibody were used to determine the specificity of shifted bands. (c) Numbers of pmel-1 Ly5.2+ CD8+ T cells in the spleen following adoptive transfer of 6 × 103 pmel-1 Tcf3flox/flox Cre-ERT2 CD8+ T cells previously activated in vitro for 5 days with or without tamoxifen to delete Tcf3. Data are representative of 6 (b) and 2 (c) independent experiments (error bars (c), s.e.m. of 3 or 4 samples). * = P < 0.05.

We next sought to ascertain whether deletion of Tcf3 in CD8+ T cells would reproduce the effect of Id3 overexpression and enhance their capacity to form long-lived memory T cells. Pmel-1 Tcf3flox/flox Cre-ERT2 CD8+ T cells were activated in vitro for five days with or without tamoxifen to conditionally delete Tcf3 (Supplementary Fig. 10)38, and then adoptively transferred in conjunction with gp100-VV infection. Deletion of Tcf3 did not affect the ability of CD8+ T cells to expand after antigenic stimulation but significantly enhanced their long-term survival recapitulating the biology of constitutive expression of Id3 (Fig. 8c). These data suggest that the inhibition of E2a transcriptional activity is critical to the pro-survival effect of Id3.

Discussion

In this study, we found that Blimp-1 directly targeted the promoter of Id3 in effector CD8+ T cells to repress its expression. Reduction of Id3 in effector T cells triggered the apoptosis of these cells limiting their capacity to enter the memory T cell pool. Enforced expression of Id3 in CD8+ T cells prolonged the survival of SLEC and enhanced the formation of TEM and recall responses. The pro-survival effects of Id3 were partly mediated through the inhibition of E2a transcriptional activity and the upregulation of genes critical for the maintenance of genome stability in rapidly dividing cells.

Studies using conditional Prdm1 knock-out mice have clearly elucidated that Blimp-1 negatively regulates CD8+ T cell memory formation5-7, but the mechanisms underlying Blimp-1 activity have thus far been poorly characterized. Blimp-1 was previously thought to impair the generation of memory CD8+ T cells solely by promoting responding T cells to develop into terminally differentiated SLEC at the expense of MPEC6, 7. Similarly to what has been seen in other mature lymphocytes2, Blimp-1 might promote terminal differentiation by suppressing the transcriptional repressor Bcl6, which in CD8+ T cells inhibits Gzmb expression39 and promotes the generation of TCM40. Here, we show that in addition to driving T cells toward senescence, Blimp-1 also triggered death in these terminally differentiated cells. This pro-apoptotic program instructed by repression of Id3 and subsequent increase in E2a transcriptional activity was characterized by the down-regulation of numerous genes necessary for the maintenance of genome integrity in proliferating cells. These findings are consistent with our observation that Id3 is dispensable for survival of naïve T cells, a relatively quiescent T cell-subset.

Furthermore, our findings shed light on the differential roles of Id protein family members in mature CD8+ T cells. During immune responses, Id3 and its homolog Id2 show an inverse pattern of expression during effector differentiation in response to infection22. Expression of Id2 was required for survival of effector CD8+ T cells during the expansion phase and therefore controlled the magnitude of the effector response22. However, Id2 deficiency did not affect the fraction of T cell undergoing apoptosis following the peak of the response and the increased numbers of WT compared to Id2−/− memory T cells were a direct reflection of the extent of effector T cell expansion22. These findings together with our results indicate that, similar to other cell-types20, Id2 and Id3 regulation and function are non-redundant in mature CD8+ T cells. Id2 appears to be critical for the short-term survival of effector T cells but it does not affect their contraction and long-term persistence. Conversely, Id3, which is enriched in MPEC, is required for their long-term survival and entry into the memory pool, but does not impact the magnitude of the effector T cell response.

Considerable efforts have been devoted to induce robust CD8+ memory T cell responses for the prevention and treatment of intracellular pathogens and cancer. By constitutively expressing Id3, we were able to prolong the survival of SLEC and generate up to 20 fold more memory T cells compared to controls. Although a substantial increase in the frequency of CD8+ memory T cells prolonged the survival of hosts challenged with B16 tumor, it did not completely protect animals from tumor uptake. These data indicate that the mere increase of memory T cell numbers alone is insufficient for effective protection and underscore the importance of qualitative aspects of memory T cells41, 42. Furthermore, our findings suggest that heterologous boost vaccination strategies which augment the frequency of memory T cells but also drive cells toward terminal differentiation43 would have limited preventative and therapeutic success. Pharmacologic modulation of Wnt-β-catenin signaling44-46 and mTOR pathways47, 48, which are emerging as critical regulators of TCM and CD8+ memory stem cells, might be a more effective strategy to generate qualitatively better memory T cells49.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. The authors have no conflicting financial interests. The authors would like to thank A. Mixon and S. Farid of the Flow Cytometry Unit for helping with Flow Cytometry analyses and sort, and Megan Bachinski for help with editing the manuscript.

Appendix

Online Methods

Mice and tumor lines

C57BL/6, Ly5.1(B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ), Id3−/− (B6.129S-Id3tm1Zhu/J), Tcf3flox/flox (B6;129S4-Tcf3tm4Zhu/J), Rag 1−/− (B6;129S7-Rag1tm1Mom/J), pmel-1 (B6.Cg-Thy1a/CyTg(TcraTcrb)8Rest/J) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory, Cre-ERT2(B6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(cre/Esr1)Arte) was purchased from Taconic. We crossed Pmel-1 mice with Rag1−/− and Id3−/− to derive pmel-1 Rag1−/− Id3−/− mice and with Tcf3flox/flox and Cre-ERT2 to derive pmel-1 Tcf3flox/floxCre-ERT2 mice. B16 (H-2Db), a gp100+ murine melanoma, and MCA205 (H-2Db), a gp100− sarcoma, were from the National Cancer Institute Tumor Repository. All mouse experiments were conducted with the approval of the National Cancer Institute Animal Use and Care Committee.

Antibodies, flow cytometry and cell sorting

We purchased all FACS antibodies from BD Biosciences except antibody to mouse CD8a (eBioscience). We used the leukocyte activation cocktail containing phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin (BD Biosciences) to stimulate T cells for intracellular cytokine staining. Flow cytometry acquisition was performed on a BD FACSCanto I or BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer. Samples were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). Naive CD8+ T cells were sorted with the BD FACSAria cell sorter.

Real-time reverse transcription-PCR

We isolated RNA with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and generated cDNA by reverse transcription (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR was performed for all genes with primers from Applied Biosystems by a Prism 7900HT (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was calculated relative to β-actin (Actb).

Immunoblotting

Protein was separated on a 4-12% SDS-PAGE gel followed by standard immunoblotting with antibodies to Id2 and Id3 (CalBioreagents), antibody to Blimp-1 (eBioscience), antibody to Gapdh (Chemicon International), antibody to β-actin and HRP-conjugated goat antibodies to mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

We performed chromatin immunoprecipitation with the Millipore 17-295 ChIP kit. DNA-protein complexes were cross-linked with formaldehyde at a final concentration of 1% and precipitated with either non-specific IgG, or ChIP-grade antibodies recognizing Blimp-1 (eBioscience). We amplified the promoter region adjacent to the transcription start site of Id3 (5′-GGTCCATGCTTTTTCTTTCTCCGTGGAAAAGG-3′ and 5′-GGGAAAAAATTAATTGCGGTGAAGCTGAGG-3′) or Csf1 (5′-AGCTGGATGCTCCCCACTTCTCCCTACAG-3′ and 5′-CAGGACTTGAATGGGGATGGACCAACG-3′) from the purified DNA-protein complex.

Retroviral vector construction and virus production

We cloned Id3 cDNA together with V5 tag and Thy-1.1 linked by a picornavirus 2A ribosomal skip peptide sequence21 into the MSGV-1 vector. Platinum Eco cell lines (Cell biolabs) were used for gamma-retroviral production. We transfected Platinum Eco cells with DNA plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and collected virus 40 hours after transfection.

In vitro activation and transduction of CD8+ T cells

We separated CD8+ T cells from non-CD8+ T cells using a MACS negative selection kit (Miltenyi Biotech) and activated them on plates coated with 2 μg ml−1 CD3-specific antibody and 1 μg ml−1 of soluble CD28-specific antibody in culture medium containing 10 ng ml−1 IL-2 (Chiron). Virus was spinoculated onto retronectin-coated (Takara) plate at 2,000 g for 2 hours at 32 °C. CD8+ T cells activated for 24 hours were spun onto the plate after aspirating the virus supernatant.

Adoptive cell transfer, Infection and tumor challenge

We performed adoptive cell transfer experiments (ranging from 6 × 102 to 3 × 105 cells dependent on experiments) and infection with recombinant vaccinia virus or fowlpox virus expressing human gp100 (rFPhgp100; Therion Biologics) as previously described. Female C57BL/6 mice were injected s.c. with 1 × 105 B16 melanoma cells.

Enumeration of adoptively transferred cells

We euthanized mice at indicated time points after infection. CD8+ T cells were enriched (MACS negative selection kit) and enumerated by trypan blue exclusion. The frequency of transferred T cells was determined by measuring CD8 and Thy-1.1, Ly5.2, or carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) with flow cytometry. The absolute number of pmel-1 cells was calculated by multiplying the total cell count with the percentage of CD8+Thy-1.1+, CD8+Ly5.2+ or CD8+CFSE+ cells.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was isolated from 106 Id3−/− or Id3+/+ and 3 × 105 Id3Thy-1.1 or Thy-1.1 pmel-1 CD8+ T cells sorted 5 days after infection using an RNEasy Micro kit (Qiagen), processed by Ambion’s WT expression kit, fragmented and labeled with a WT Terminal Labeling Kit (Affymetrix), hybridized to WT Mouse Gene 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix) and stained on a Genechip Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix). Microarrays were scanned on a GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G (Affymetrix). Raw data from the generated .CEL files were imported into Partek Genomincs Suite using the RMA method. Probe-set level data were merged into gene-level datasets based on median probe-set signal level. To accurately assess the amount of functional Id3 mRNA in engineered CD8+ T cells, Id3-specific probe-sets specific for transcript segments other than those affected by transgenic manipulation were excluded from all analyses. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by Partek’s Two-Way ANOVA incorporating both the experimental batch and transgenic up- or down-regulation of Id3 as factors in the analysis. DEGs were filtered by the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate procedure (P < 0.05) and a between group fold change criterion of > 1.3 (P < 0.05). Pathway Analysis was performed on the identified DEG lists using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis system.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

We isolated nuclear extracts with the nuclear extraction kit (Thermo scientific) and incubated them (5 μg protein) with Biotin 3′-labeled oligonucleotide probes (sense: 5′-AGCTCCAGAACACCTGCAGCAG-3′; antisense: 5′-CTGCTGCAGGTGTTCTGGAGCT-3′), containing the E protein binding motif 5′-AACACCTGCA-3′. Unlabeled oligonucleotide probes were used as competitors. E2a specific antibody (BD Biosciences) and non-specific IgG were used to detect specificity. Samples were loaded onto the NativePAGE™ Novex 3-12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane before exposure to X-ray film.

Statistical analyses

The One-tailed or Two-tailed unpaired t test was used for our data comparisons based on the experimental hypothesis. Log-rank Test was used to analyze survival curves.

Footnotes

Accession codes

GEO: microarray data, GSE23568.

Author contributions

Y. J., Z. P., M. R., C. A. K., Z. Y., M. S., R. N. R., D. C. P., Z. A. B., L. G. carried out experiments; Y. J., Z. P., M. R., C. A. K., E. W., L. G. analyzed experiments; Y. J., Z. P., P. M., D. S. F. M. M., N. P. R., L. G. designed experiments; Y. J., N. P. R., L. G. wrote the manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.Turner CA, Jr., Mack DH, Davis MM. Blimp-1, a novel zinc finger-containing protein that can drive the maturation of B lymphocytes into immunoglobulin-secreting cells. Cell. 1994;77:297–306. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crotty S, Johnston RJ, Schoenberger SP. Effectors and memories: Bcl-6 and Blimp-1 in T and B lymphocyte differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:114–120. doi: 10.1038/ni.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magnusdottir E, et al. Epidermal terminal differentiation depends on B lymphocyte- induced maturation protein-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:14988–14993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707323104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishikawa K, et al. Blimp1-mediated repression of negative regulators is required for osteoclast differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:3117–3122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912779107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin H, et al. A role for the transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 in CD8(+) T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2009;31:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutishauser RL, et al. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 promotes CD8(+) T cell terminal differentiation and represses the acquisition of central memory T cell properties. Immunity. 2009;31:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kallies A, Xin A, Belz GT, Nutt SL. Blimp-1 transcription factor is required for the differentiation of effector CD8(+) T cells and memory responses. Immunity. 2009;31:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshi NS, et al. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarkar S, et al. Functional and genomic profiling of effector CD8 T cell subsets with distinct memory fates. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:625–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belz GT, Kallies A. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation: toward a molecular understanding of fate determination. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2010;22:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutishauser RL, Kaech SM. Generating diversity: transcriptional regulation of effector and memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Immunol. Rev. 2010;235:219–233. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ichii H, et al. Role for Bcl-6 in the generation and maintenance of memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:558–563. doi: 10.1038/ni802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martins GA, Cimmino L, Liao J, Magnusdottir E, Calame K. Blimp-1 directly represses Il2 and the Il2 activator Fos, attenuating T cell proliferation and survival. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:1959–1965. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martins G, Calame K. Regulation and functions of Blimp-1 in T and B lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:133–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaffer AL, et al. Blimp-1 orchestrates plasma cell differentiation by extinguishing the mature B cell gene expression program. Immunity. 2002;17:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Overwijk WW, et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivera RR, Johns CP, Quan J, Johnson RS, Murre C. Thymocyte selection is regulated by the helix-loop-helix inhibitor protein, Id3. Immunity. 2000;12:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maruyama T, et al. Control of the differentiation of regulatory T cells and T(H)17 cells by the DNA-binding inhibitor Id3. Nat. Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ni.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verykokakis M, Boos MD, Bendelac A, Kee BL. SAP protein-dependent natural killer T-like cells regulate the development of CD8(+) T cells with innate lymphocyte characteristics. Immunity. 2010;33:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokota Y. Id and development. Oncogene. 2001;20:8290–8298. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szymczak AL, et al. Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single 'self- cleaving' 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cannarile MA, et al. Transcriptional regulator Id2 mediates CD8+ T cell immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:1317–1325. doi: 10.1038/ni1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan L, Sato S, Frederick JP, Sun XH, Zhuang Y. Impaired immune responses and B-cell proliferation in mice lacking the Id3 gene. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999;19:5969–5980. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibarra A, Schwob E, Mendez J. Excess MCM proteins protect human cells from replicative stress by licensing backup origins of replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:8956–8961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803978105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarvinen TA, Liu ET. Topoisomerase IIalpha gene (TOP2A) amplification and deletion in cancer--more common than anticipated. Cytopathology. 2003;14:309–313. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-5507.2003.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Cancer-susceptibility genes. Gatekeepers and caretakers. Nature. 1997;386(761):763. doi: 10.1038/386761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loffler H, Lukas J, Bartek J, Kramer A. Structure meets function--centrosomes, genome maintenance and the DNA damage response. Exp. Cell Res. 2006;312:2633–2640. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moynahan ME, Jasin M. Mitotic homologous recombination maintains genomic stability and suppresses tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:196–207. doi: 10.1038/nrm2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warner SL, Gray PJ, Von Hoff DD. Tubulin-associated drug targets: Aurora kinases, Polo-like kinases, and others. Semin. Oncol. 2006;33:436–448. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wonsey DR, Follettie MT. Loss of the forkhead transcription factor FoxM1 causes centrosome amplification and mitotic catastrophe. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5181–5189. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie S, Xie B, Lee MY, Dai W. Regulation of cell cycle checkpoints by polo-like kinases. Oncogene. 2005;24:277–286. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holland AJ, Cleveland DW. Boveri revisited: chromosomal instability, aneuploidy and tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:478–487. doi: 10.1038/nrm2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balatoni CE, et al. Epigenetic silencing of Stk39 in B-cell lymphoma inhibits apoptosis from genotoxic stress. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;175:1653–1661. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenbaum S, Lazorchak AS, Zhuang Y. Differential functions for the transcription factor E2A in positive and negative gene regulation in pre-B lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:45028–45035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400061200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin YC, et al. A global network of transcription factors, involving E2A, EBF1 and Foxo1, that orchestrates B cell fate. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:635–643. doi: 10.1038/ni.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kee BL. E and ID proteins branch out. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:175–184. doi: 10.1038/nri2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan L, Hanrahan J, Li J, Hale LP, Zhuang Y. An analysis of T cell intrinsic roles of E2A by conditional gene disruption in the thymus. J. Immunol. 2002;168:3923–3932. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshida K, et al. Bcl6 controls granzyme B expression in effector CD8+ T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006;36:3146–3156. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ichii H, Sakamoto A, Kuroda Y, Tokuhisa T. Bcl6 acts as an amplifier for the generation and proliferative capacity of central memory CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2004;173:883–891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Restifo NP. CD8+ T-cell memory in tumor immunology and immunotherapy. Immunol. Rev. 2006;211:214–224. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, Ahmed R. From vaccines to memory and back. Immunity. 2010;33:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wirth TC, et al. Repetitive antigen stimulation induces stepwise transcriptome diversification but preserves a core signature of memory CD8(+) T cell differentiation. Immunity. 2010;33:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gattinoni L, et al. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat. Med. 2009;15:808–813. doi: 10.1038/nm.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gattinoni L, Ji Y, Restifo NP. Wnt/{beta}-catenin signaling in T-cell immunity and cancer immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:4695–4701. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gattinoni L, et al. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat. Med. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nm.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Araki K, et al. mTOR regulates memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;460:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pearce EL, et al. Enhancing CD8 T-cell memory by modulating fatty acid metabolism. Nature. 2009;460:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Restifo NP. Pharmacologic induction of CD8+ T cell memory: better living through chemistry. Sci. Transl. Med. 2009;1:11ps12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.