Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To examine the effects of a community-based group exercise program for older individuals with chronic stroke.

DESIGN

Prospective, single-blind, randomized controlled intervention trial.

SETTING

Intervention was community-based. Data collection was performed in a research laboratory located in a rehabilitation hospital.

PARTICIPANTS

Sixty-three older individuals (≥50 years) with a chronic stroke (post-stroke duration ≥ 1 year) who were living in the community.

INTERVENTION

Participants were randomized into intervention group (n=32) or control group (n=31). The intervention group underwent a Fitness and Mobility Exercise (FAME) program designed to improve cardiorespiratory fitness, mobility, leg muscle strength, balance and hip bone mineral density (BMD) (1-hour sessions, 3 sessions/week, for 19 weeks). The control group underwent a seated upper extremity program.

MEASUREMENTS

(1) cardiorespiratory fitness (maximal oxygen consumption), (2) mobility (Six Minute Walk Test), (3) leg muscle strength (isometric knee extension), (4) balance (Berg Balance Scale), (5) activity and participation (Physical Activity Scale for Individuals with Physical Disabilities) and (6) femoral neck BMD (Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry).

RESULTS

The intervention group had significantly more gains in cardiorespiratory fitness, mobility, and paretic leg muscle strength than controls. Femoral neck BMD of the paretic leg was maintained in the intervention group whereas a significant decline of the same occurred in controls. There was no significant time × group interaction for balance, activity and participation, non-paretic leg muscle strength and non-paretic femoral neck BMD.

CONCLUSION

The FAME program is feasible and beneficial for improving some of the secondary complications resulting from physical inactivity in older adults living with stroke. It may serve as a good model of community-based fitness program for preventing secondary diseases in older adults living with chronic conditions.

Keywords: cerebrovascular accident, health promotion, osteoporosis, rehabilitation

The consequences of physical inactivity are particularly detrimental in older individuals with chronic disease. Impairments resulting from chronic disease (e.g., reduced mobility, pain), in addition to the lack of accessible and appropriate community-based exercise programs could lead to further sedentary lifestyle, and additional declines in functional status.1 Physical inactivity could also contribute to secondary debilitating or life-threatening diseases. A recent study has found that approximately one third of cardiac disease and osteoporosis cases are attributable to lack of physical activity and have posed tremendous burden on the health care system.2

Stroke is one of the most common chronic conditions seen in older adults, with an incidence approximately doubling each decade after the age of 55.3 Most stroke survivors continue to live with residual physical impairments, which may promote a sedentary lifestyle and resultant secondary complications.4 One of the secondary complications commonly observed following stroke is poor cardiorespiratory fitness.5,6 Low cardiorespiratory fitness is related to poor functional performance7 and increased risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease.8,9 Indeed, cardiac events and recurrent stroke are major occurrences in stroke survivors.10,11

Other common stroke impairments are poor balance and muscle weakness,12–14 which may contribute to the higher incidence of falls in older adults with stroke than the age-matched population.15 In addition, poor mobility and decreased loading of the hemiparetic leg may also result in decline of hip bone mineral density (BMD).16,17 The increased falls and reduced bone health may in part explain the two to four time greater hip fracture risk among stroke survivors.18

These secondary conditions seen in stroke survivors are compounded by the fact that the number of older individuals with chronic stroke in the community is on the rise. Studies have shown that the incidence of stroke is increasing, particularly in older people.3 The mortality rate of stroke, however, has been declining3 and more stroke survivors are returning home instead of going into an inpatient rehabilitation program.19 These factors may translate into an increasing number of older adults living with a chronic stroke in the community, who have not attained optimal functional recovery and are at risk of developing secondary complications due to physical inactivity.

There has been an increasing recognition of the importance of health promotion for people with disabilities.20 One of the key components of health promotion for people with disabilities is “the prevention of health complications (medical secondary conditions) and further disabling conditions”.20 According to the conceptual model of health promotion proposed by Rimmer20, community-based fitness programs play one important role in achieving this objective. Considering that physical inactivity in older adults with chronic stroke could lead to devastating secondary health complications, an accessible and multidimensional fitness program is urgently needed.21 Most exercise programs proposed for chronic stroke, however, are not community-based and have addressed only one or two of the impaired domains.5,6,22–24 Moreover, although it is known that stroke is a major risk factor for hip fracture,18 no study has examined the effects of exercise on hip BMD in stroke. This study aims to assess the efficacy of a multidimensional community-based fitness and mobility exercise (FAME) program for individuals with chronic stroke. This is the first study to examine the effects of exercise on hip BMD in this population. It was hypothesized that the individuals who underwent the FAME program would have significantly more improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness, mobility, leg muscle strength, balance, activity and participation, and hip BMD than those in the control group.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited from a local rehabilitation hospital database, community stroke clubs and local newspaper advertisements. All potential participants were first screened by a telephone interview based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) a single stroke >1 year onset, (2) age ≥50 years, (3) ability to walk >10 meters independently (with or without walking aids), and (4) living at home. Exclusion criteria were: (1) history of serious cardiac disease (i.e. myocardial infarction), (2) uncontrolled blood pressure (systolic blood pressure >140, diastolic blood pressure >90), (3) pain while walking, (4) neurological conditions in addition to stroke, and (5) other serious diseases that preclude the individual from participating in the study.

Those who fulfilled the above criteria were required to provide informed and written consent. In addition, the primary care physician was required to provide written information regarding medical history of the individual (i.e. diagnosis, comorbid conditions) and his/her recommendation about the participant’s participation. The study was approved by the local university and hospital ethics committees. The experiments were conducted in accordance to the Helsinki Declaration.25

Once the required consent and information were obtained, the participant was brought into the laboratory for further screening. First, the functional classification level of the American Heart Association Stroke Outcome Classification was used to measure residual disability in basic (e.g. dressing, bathing, grooming) and instrumental activities of daily living (e.g. shopping, preparing meals) (BADL and IADL) [level I = as independent as before the stroke; level V = completely dependent in BADL and IADL].26 Second, the ability to pedal the cycle ergometer (Excalibur, Lode B.V. Medical Technology, Groningen, Netherlands) was tested. The participant had to be able to pedal at 60rpm and raise the heart rate to at least 60% maximal heart rate. Third, since significant cognitive deficits may adversely affect an individual’s ability to follow instructions during the exercise sessions, the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) was administered and a score >22 had to be fulfilled for inclusion.27

Study Design

A prospective, single-blind, randomized controlled intervention trial was undertaken. The participants were stratified according to gender because men tended to have higher VO2max,28 muscle strength,28 and BMD29 than women. The participants were then randomly assigned to the intervention or control group by drawing ballots marked “I” (i.e. intervention) or “C” (i.e. control). The randomization was performed by an individual who was not involved in enrollment or any of the screening and outcome assessments. The research personnel who performed the outcome assessments were blinded to the group assignment. Participants were not blinded to group assignment. They were informed that they were in either a lower extremity or upper extremity program. Participants were instructed not to tell the assessors about the group assignment or the treatment they received and not to discuss the protocol with the stroke community.

Interventions

Both the intervention and control groups underwent an exercise program for 19 weeks (1-hour sessions, 3 sessions per week) in the same multi-purpose room of a community hall. The community space was only occupied by the participants during the exercise sessions. The two groups exercised at different times of the day. In each session, 9–12 participants were supervised by a physical therapist, an occupational therapist and an exercise instructor. Hip protectors (SAFEHIP, Tutex, Denmark) were provided to those in the intervention group and they were instructed to wear them in each session.

In the intervention group, the Fitness and Mobility Exercise (FAME) program was provided (Table 1). To determine cardiorespiratory training intensity, the maximum heart rate achieved at the end of the cycle ergometer test was used to calculate the heart rate reserve (HRR).28 As the trial progressed, both the exercise intensity and duration was increased as tolerated (Table 1), as adapted from the guidelines recommended by American College of Sports Medicine.28 During aerobic exercise training, the participant wore a heart rate monitor (Polar A3, Polar Electro Inc., Woodbury, NY, USA) and was instructed to exercise within the set target heart rate zone. The average heart rate attained, the duration over which the target heart rate was sustained, and the specific exercises completed in each session were recorded. The control group underwent a seated upper extremity program (Table 2). No aerobic exercises, leg strengthening and balance training were given. Adverse events (e.g. falls) were monitored and recorded. A fall was defined as unintentionally coming to rest on the floor or another lower level.

Table 1.

Fitness and Mobility Exercise Program (FAME) Provided to Intervention Group

Station 1: Cardiorespiratory fitness and mobility

|

| Duration: 10 minutes initially, with increment of 5 minutes every week, up to 30 minutes of continuous exercise as tolerated. |

| Intensity: Started at 40–50% HRR, with increment of 10% HRR every 4 weeks, up to 70–80% HRR, as tolerated. |

Station 2: Mobility and balance

|

| Progressed by reducing arm support and/or by increasing speed of movement. |

Station 3: Leg muscle strength

|

| Progressed by increasing number of repetitions (from 2 sets of 10 to 3 sets of 15) and/or by reducing arm support. |

HRR = heart rate reserve

Table 2.

Upper Extremity Program Provided to Control Group

Station 1: Shoulder muscle strength

|

Station 2: Elbow/wrist muscle strength and range of motion

|

Station 3: Hand activities

|

Outcomes

All outcomes were measured by the same trained assessors immediately before the commencement of the interventions, and again immediately after the termination of the interventions.

Maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) was considered to be the criterion measure of cardiorespiratory fitness.28 Each participant underwent a maximal exercise test on the Excalibur cycle ergometer. A 12-lead electrocardiography system (Quark C12, COSMED Srl, Rome, Italy) was used to monitor cardiac activity by a physician. Participants wore a face mask and VO2 was continuously measured using a portable metabolic unit, which performed breath by breath gas analysis (Cosmed K4 b2 system; COSMED Srl; Rome, Italy). The level of perceived exertion was monitored by the 16-point Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion scale.30 Blood pressure was measured at rest and also at the end of the test. The testing protocol was adjusted to the capabilities of the individuals.28 The workload started at 20W and increased by 20W/min for 29 participants. For the other 34 participants who were more severely impaired, the workload started at 10W with increments of 10W/min. For each participant, the same seat height and testing protocol were used at baseline and 19 weeks. Participants were required to pedal at 60 rpm. The test continued until the participant volitionally fatigued. The respiratory exchange ratio (RER) at the end of the test was noted. The VO2 data were averaged at a rate of every 15 seconds. The maximal value obtained was considered to be the VO2max (ml/kg/min).

Six Minute Walk Test (6MWT) was used to assess mobility.31 The distance walked in 6 minutes were recorded. 6MWT has been shown to be a reliable method to assess walking performance in individuals with stroke.32 Hand-held dynamometry (Nicholas MMT, Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN, USA) was used to evaluate isometric knee extension strength. The participant was sitting upright in a chair with back support. The knee was placed in 90° flexion and the thigh was stabilized by the assessor in order to eliminate synergistic movements. Each participant was asked to perform a maximal isometric contraction of knee extension. Three trials were performed on each side and force data [Newtons (N)] were averaged. Hand-held dynamometry is a reliable method to assess muscle strength in stroke.33 Functional balance was assessed by Berg Balance Scale (maximal score = 56), which has shown to be a reliable and valid tool to assess balance in older adults.34 Activity participation was measured by the Physical Activity Scale for Individuals with Physical Disabilities (PASIPD).35 It is a 13-item questionnaire which assesses the amount of participation in physical activities of different intensities for the past 7 days. Each activity was assigned a specific metabolic equivalent (MET) value and the maximal score was 199.5 MET hour/day. The validity of PASIPD has been established.35

Bilateral hip scans were performed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA; Hologic QDR 4500, Hologic Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). All scans were performed by the same technician using standard procedures (Hologic User’s Manual). Femoral neck BMD (g/cm2) was reported as the primary outcome, since femoral neck is the most common site of fracture in stroke.18 Each participant was classified as having osteoporosis or osteopenia according to the definitions of the World Health Organization,36 using the reference data provided by Looker et al.29 Regarding the precision of the DXA scanner, the coefficient of variation for femoral neck BMD was .93%.

Statistical Methods

The sample size was based on predictions of change for cardiorespiratory fitness. A power of .80 and a P < .05 were desired for the calculation. Based on an average VO2max of 17.3 ml/kg/min (SD = 3.0)5 and a desired 15% change,6 21 participants per group were required. To account for a 20% attrition rate, at least 26 participants per group should be recruited.

Baseline variables between the two groups were compared using independent t-tests (for continuous variables) and Chi-Square (for categorical variables). Intention-to-treat analysis was performed. For dropouts, it was conservatively assumed that no changes occurred in any of the outcome measures at 19 weeks. Therefore, the missing values at 19 weeks were inputted using baseline values for these individuals.37 To reduce the probability of type I error from multiple comparisons, a single multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) incorporating all primary outcomes was performed to determine whether there was an overall significant time × group interaction. Two-way ANOVA (within factor: time; between factor: group) were then performed to analyse the data post-hoc. The difference between the pre-test and post-test scores and 95% confidence interval for each outcome variable were also reported. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS11.5 software (SPSS Inc.) using a significance level of 0.05 (2-tailed).

RESULTS

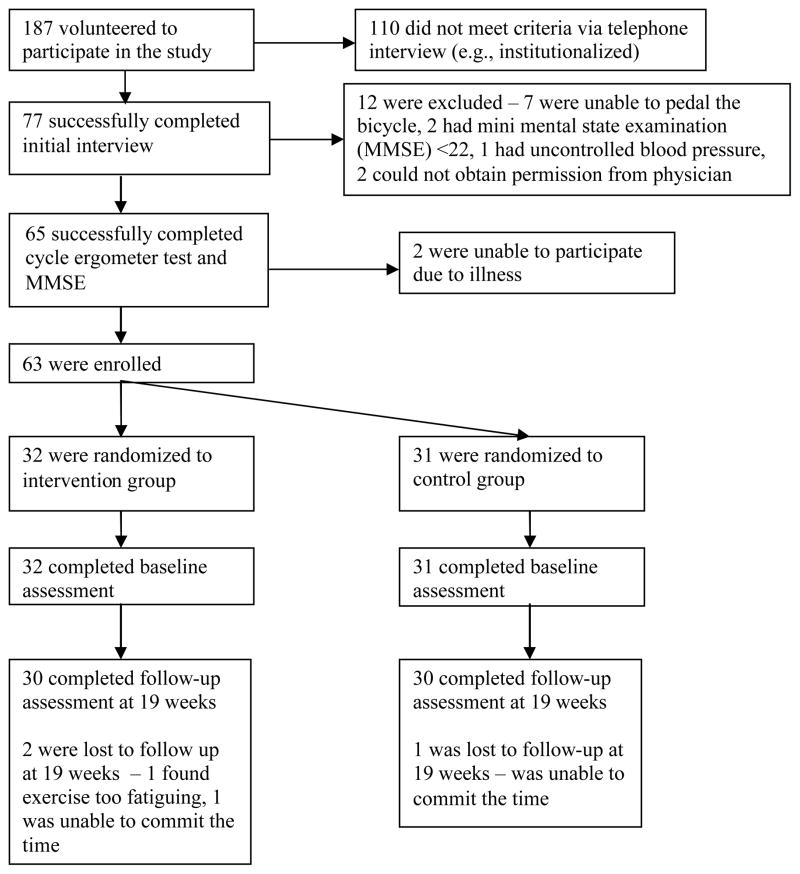

Sixty three individuals fulfilled all criteria and were enrolled in the study (Figure 1). There were 3 dropouts. Two dropped out of the intervention group: 1 withdrew after 6 sessions because of the inability to commit the time, 1 withdrew after 9 sessions because he found the exercise too fatiguing. One dropped out of the control group after 8 sessions because of the inability to commit the time. The dropouts tended to have better balance (mean Berg = 54.0) and mobility (mean 6MWT distance = 498.3m). There was no significant difference in any of the variables between the intervention and control groups at baseline (P > .200 for all variables) (Table 3 and 4).

Figure 1. Study Flow Chart.

Sixty three individuals were enrolled in the study and were randomly assigned to either the intervention (n=32) or control group (n=31). Thirty individuals in each group completed the program.

Table 3.

Subject Characteristics

| Intervention Group (n=32) | Control Group (n=31) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Female gender (n) | 13 | 13 |

| Age (years) | 65.8(9.1) | 64.7(8.4) |

| Caucasian/Asian/Black (n) | 20/11/1 | 18/13/0 |

| Walking aid (walker/crutch/quad cane/cane) (n) | 6/1/1/3 | 5/0/2/2 |

| AHA Stroke Functional Classification (I/II/III/IV/V) (n) | 5/17/9/1/0 | 2/19/8/2/0 |

| Mini Mental Status Examination score | 27.6(2.3) | 28.2(1.9) |

| Education (years) | 13.9(3.8) | 13.9(3.4) |

| Had inpatient rehabilitation after acute hospital stay (n) | 24 | 26 |

| Had outpatient physical therapy after discharge home (n) | 20 | 21 |

| Stroke characteristics | ||

| Paretic side (left) (n) | 19 | 22 |

| Ischemic stroke (n) | 18 | 19 |

| Post-stroke duration (years) | 5.2(5.0) | 5.1(3.6) |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Hypertension (n) | 17 | 20 |

| Diabetes (n) | 4 | 6 |

| Arthritis (n) | 6 | 6 |

| Depression (n) | 7 | 8 |

| Osteopenia/osteoporosis | ||

| Paretic femoral neck (n) | 17/3 | 14/6 |

| Non-paretic femoral neck (n) | 19/2 | 15/5 |

| Medications/supplements | ||

| Beta-blockers (n) | 4 | 5 |

| Bone resorption inhibitors (n) | 2 | 3 |

| Calcium (n) | 6 | 6 |

| Multivitamins (n) | 8 | 7 |

The mean values are presented unless indicated otherwise. The standard deviations are in brackets.

n = number of participants; AHA = American Heart Association

Table 4.

Outcome Measurements

| Outcome Measures | Intervention group (n=32) | Control group (n=31) | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | Δ (95%CI)* | Pre-test | Post-test | Δ (95%CI)* | ||

| Primary outcomes | |||||||

| VO2max (ml/kg/min) | 22.5 (5.2) | 24.5 (5.3) | 2.0 (0.8,3.1) | 21.5 (4.3) | 21.8 (4.5) | 0.3 (−0.8,1.4) | .034† |

| 6MWT distance (m) | 328.1 (143.5) | 392.7 (151.1) | 64.5 (45.3,83.8) | 304.1 (123.8) | 342.4 (133.4) | 38.4 (25.6,51.1) | .025† |

| Paretic leg muscle strength (N) | 182.6 (74.3) | 223.2 (99.9) | 40.6 (21.0,60.2) | 194.9 (68.8) | 205.3 (79.4) | 10.4 (−5.1,25.9) | .017† |

| Non-paretic leg muscle strength (N) | 248.5 (85.6) | 276.7 (88.8) | 28.2 (7.4,49.2) | 265.6 (87.8) | 272.0 (84.0) | 6.4 (−12.4,25.2) | .119 |

| Berg Balance Score‡ | 47.6 (6.7) | 49.6 (4.4) | 2.1 (0.8,3.3) | 47.3 (6.1) | 49.2 (5.8) | 1.9 (0.8,3.0) | .846 |

| PASIPD (METhour/day) § | 7.9 (7.8) | 13.7 (10.9) | 5.8 (1.9,9.7) | 10.6 (9.8) | 18.6 (16.8) | 8.0 (3.6,12.4) | .452 |

| Paretic femoral neck BMD (g/cm2) | 0.73 (0.13) | 0.72 (0.14) | −0.00 (−0.02,0.01) | 0.72 (0.15) | 0.70 (0.15) | −0.02 (−0.03, −0.01) | .043† |

| Non-paretic femoral neck BMD, (g/cm2) | 0.72 (0.12) | 0.72 (0.l2) | −0.01 (−0.02,0.00) | 0.74 (0.17) | 0.74 (0.17) | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.01) | .113 |

| Secondary outcomes (cycle ergometry) | |||||||

| RER | 1.13 (0.13) | 1.17 (0.14) | 0.04 (0.00,0.09) | 1.11 (0.11) | 1.19 (0.13) | 0.08 (0.03,0.12) | .233 |

VO2max=maximal oxygen consumption; 6MWT=Six Minute Walk Test; N=Newtons; PASIPD=Physical Activity Scale for Individuals with Physical Disabilities; MET=metabolic equivalents; BMD=bone mineral density; RER=respiratory exchange ratio

Standard deviations and confidence intervals are in brackets.

Δ(95%CI)=change from pre-test to post-test (95% confidence interval, paired t-tests)

P<.050 (time × group interaction, 2-way analysis of variance)

Total range of scores for Berg balance test = 0–56

Total range of scores for PASIPD = 0.0–199.5 MET hour/day

On average, the two groups attended a similar number of sessions (intervention group: 81.4%; controls group: 80.4%). For cardiorespiratory training in the intervention group, six participants could not progress beyond the initial target heart rate zone (40–50% HRR). These 6 participants tended to have poorer balance (mean Berg = 41.2) and mobility (mean 6MWT distance = 193.9m) at baseline. None of these six participants were on beta-blockers. Seven participants were trained at 70–80% HRR at the end of the trial. An additional 12 and 5 participants reached 60–70% and 50–60% HRR, respectively. On average, the target heart rate was sustained for 15 minutes.

Multivariate analysis showed a significant time × group interaction (Wilk’s Lambda = .670, P = .004), indicating that overall, the FAME program produced more gains than the control treatment. Elimination of the 3 dropouts from the analysis produced similar results (Wilk’s Lambda = .644, P = .003). Post-hoc analysis (Table 4) revealed that the intervention group had significantly more improvements in VO2max, 6MWT distance, and paretic leg muscle strength than controls. A significant time × group interaction was also found for the paretic femoral neck BMD where there was a 2.5% decline in controls but a maintenance of BMD in the intervention group. Both groups improved in balance and PASIPD score, but there was no significant time × group interaction.

Given the positive improvements from the FAME Program, additional post-hoc analyses were performed to examine the relationship between the initial level of impairment and the amount of improvement (i.e., change score) in the intervention group using Pearson’s correlations for each primary outcome. In the intervention group, there was a significant negative correlation between the baseline score and the change score for two of the primary outcomes, namely, Berg (r = −.817, P < .001) and PASIPD (r = −.358, P = .044). However, correlations were not significant between the baseline and change scores for the other outcome measures (i.e. VO2max, 6MWT distance, leg muscle strength, and femoral neck BMD).

There were 5 falls (4 participants) in the intervention group. Three falls occurred with the participant still holding onto a support (e.g., knee gave way while in a squat position) but were still considered falls as the participant came to rest on a lower level. One fall occurred when the participant was kicking a ball. Another fall occurred when the participant was stepping down from a 2-inch-thick foam. In both cases, the participants were being spotted and were able to recover independently immediately after the fall. Most falls were thus low-impact. One fall occurred in the control group while the participant was walking. No injuries were reported.

DISCUSSION

The study showed that the proposed FAME program is feasible and beneficial for improving cardiorespiratory fitness, mobility, paretic leg muscle strength and maintaining hip BMD in individuals with chronic stroke. The program may provide a good model for community-based fitness programs for older people with chronic disabilities.

The results support the hypothesis that the intervention group would have significantly more gains in cardiorespiratory fitness. The FAME program resulted in significantly more improvement in VO2max (10.7%) than controls (2.2%). The amount of gain in VO2max is comparable to other stroke programs (duration: 10–12 weeks) which used a cycle ergometer or treadmill for cardiorespiratory training.6,24,37 The difference in results between the intervention and control groups could not be due to difference in effort during the maximal exercise test, since the RER achieved at the end of the ergometer test showed no group × time interaction. The average baseline VO2max obtained in the participants of this study was approximately at the 10th percentile of the age and sex-matched population, indicating poor cardiorespiratory fitness.28 Individuals with low VO2max values need to work at a higher relative exercise intensity to complete the same daily functional activities, when compared with others who have higher VO2max. This reduction in fitness reserve can contribute to reduced activity endurance, which was identified as the most striking area of difficulty for older adults with stroke living in the community.19 Thus, improvement in VO2max in older adults with stroke may have tremendous impact on functional abilities.

Apart from its influence on function, low VO2max has also been related to an increased risk of various forms of cardiovascular diseases8,39 and premature death from all causes and specifically from cardiovascular disease.40,41 Our findings thus have important implications for stroke survivors, considering that poor VO2max is prevalent in this group5,6 and that a large proportion (up to75%) of older individuals with stroke demonstrate some form of cardiovascular disease.10 Cardiac disease is also the leading cause of death in stroke survivors.10

Six participants were unable to progress beyond the initial training target heart rate zone. Reduced ambulatory and balance skills may make it more difficult for them to increase walking speed as training progressed. Despite the failure to train beyond 40–50%HRR, these six individuals still averaged an impressive 18.4% increase in VO2max. These individuals (3 women, 3 men) tended to have lower baseline VO2max (mean = 20.2ml/kg/min), which would partially explain their higher percent gain. Thus, positive outcomes can be obtained despite training at low intensities. This is in agreement with the previous finding that intensity as low as 30% VO2 reserve (i.e. the difference between maximum and resting VO2)was effective in improving cardiorespiratory fitness in less fit, but healthy individuals.42

The intervention group also improved significantly more in 6MWT distance and paretic leg muscle strength than the control group, as predicted by the research hypothesis. The improvement in 6MWT distance is particularly important, given that the deficit in walking endurance is strikingly pronounced in individuals with chronic stroke.19 Muscle strength is correlated with gait velocity,32 walking endurance32,43 and BMD44 in individuals with stroke. Since decreased ambulatory capacity19,32 and osteoporosis16,44 are major concerns for this group, increasing muscle strength may also have important implications.

Previous studies in older adults have reported beneficial effects of exercise on bone health. For example, Vincent and Braith reported that a 6-month high-intensity resistance exercise program resulted in a significant 2.0% increase in femoral neck BMD in elderly men and women while the controls had a 1.6% decrease of the same.45 A 1-year high-impact aerobic exercise program for older adults over 50 years of age resulted in a maintenance of hip BMD compared to a significant 1.9% reduction of the same in controls.46

This study provides the first evidence that regular exercise is beneficial for hip bone health in the chronic stroke population. Femoral neck BMD on the paretic side was maintained in the intervention group whereas a significant 2.5 % decrease was observed in controls. In this study, it was assumed that the pre-test and post-test scores for each primary outcome variable were the same for the dropouts. It is thus possible that the paretic hip BMD of the dropout in the control group may have been overestimated. However, this possibility would not affect the interpretation of the results. First, the number of dropouts in the control group is small (n = 1). Second, overestimating the post-test paretic hip BMD value of dropouts in the control group would actually tend to underestimate the difference in post-test scores between the intervention and control groups. Despite this, the results remained statistically significant.

The reduction of BMD in the control group (2.5%) is consistent with the study by Ramnemark et al.,16 who reported a 2.2% decline in proximal femur BMD in a 5-month period in a sample containing mostly ambulatory subjects with stroke. The reduction in BMD reported in this study is clinically significant, considering that femoral neck BMD in older men and women (70–79 years) is only 5.5% and 9.4% lower than those 10 years younger, respectively.36 With the presence of risk factors such as poor balance and mobility, any departure from healthy BMD values would further increase the risk of hip fractures.47 It is well known that mechanical loadingis important to maintain bone mineral. 48 Reduced VO2max, poor mobility and reduced weight-bearing have also been linked to low femoral neck BMD.17,49 By targeting these specific impairments and incorporating weight-bearing activities with the paretic leg, the FAME program succeeded in maintaining femoral neck BMD in chronic stroke.

The results, however, do not support the hypothesis that the intervention group would have more improvement in balance and PASIPD scores than the control group. The improvement of balance in the control group may be due to the undertaking of several activities which involved trunk stability and reaching function, which may improve lower limb weight-bearing and sit-to-stand function.22 The absence of between-group difference in PASIPD score may be explained by the fact that the control group also underwent an intensive exercise program, which may in turn promote activity and participation.

The study has several limitations. First, the results are generalizable to a selected group of community-dwelling individuals with chronic stroke only. Second, except for balance and PASIPD, the amount of improvement in the intervention group was not specific to the initial level of impairment and perhaps factors like motivation played an important role. More improvement in balance was correlated with a lower baseline Berg score. However, this correlation should be interpreted with caution as the Berg scale does have a ceiling effect with higher levels of balance function.50 Third, no attempts were made to help participants to develop exercise habits on a long-term basis. It is not known whether the participants continued to exercise after the termination of the program. A larger sample size and long-term follow-up would be required to determine the long-term benefits as well as adherence to an ongoing exercise program. It would also be interesting to determine whether the FAME program would reduce the actual risk of cardiac events, osteoporosis or fractures. Whether extending the duration of the program would increase femoral neck BMD also requires further study. Nevertheless, the positive outcomes from this trial justify a multi-centered trial to further study the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the FAME program.

Acknowledgments

Sponsor’s Role:

None

Funding:

M.Y.C.P. was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. This study was supported by a grant-in-aid from the Heart Stroke Foundation of British Columbia and Yukon (J.J.E.) and from career scientist awards from Canadian Institute of Health Research (J.J.E) (MSH-63617) and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (J.J.E. and H.A.Mc.).

Footnotes

Presentation at international meeting:

The findings of this study were presented in the American Physical Therapy Association Combined Sections Meeting 2005, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA on February 25–26, 2005.

Author Contributions:

Marco Y.C. Pang: study concept and design, acquisition of subjects and data, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript

Janice J. Eng: study concept and design, preparation of manuscript

Andrew S. Dawson: study concept and design, preparation of manuscript

Heather A. McKay: study concept and design, preparation of manuscript

Jocelyn E. Harris: study concept and design, preparation of manuscript

Financial Disclosure: No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this paper has or will confer a benefit upon the author(s) or upon the organization with which the author(s) is/are associated.

Marco Y.C. Pang: supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Janice J. Eng: supported by a grant-in-aid from the Heart Stroke Foundation of British Columbia and Yukon and from a career scientist award from Canadian Institute of Health Research (MSH-63617).

Andrew S. Dawson: none

Heather A. McKay: supported by a career scientist award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Jocelyn E. Harris: none

References

- 1.Mol V, Baker D. Activity intolerance in the geriatric stroke patient. Rehabil Nurs. 1991;16:337–343. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.1991.tb01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrett NA, Brasure M, Schmitz KH, et al. Physical inactivity. Direct cost to a Health Plan. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. Stroke epidemiology: a review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, et al. Stroke: Neurologic and functional recovery. The Copenhagen Study. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 1999;10:887–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu KS, Eng JJ, Dawson AS, et al. A randomized controlled trial of water-based exercise for cardiovascular fitness in individuals with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:870–874. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potempa K, Lopez M, Braun LT, et al. Physiological outcomes of aerobic exercise training in hemiparetic stroke patients. Stroke. 1995;26:101–105. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binder EF, Birge SJ, Spina R, et al. Peak aerobic power is an important component of physical performance in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M353–356. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.7.m353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers MA, Yamamoto C, Hagberg JM, et al. The effects of 7 years of intense exercise training on patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10:32–326. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurl S, Laukanen JA, Rauramaa R, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and the risk for stroke in men. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1682–1688. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.14.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth EJ. Heart disease in patients with stroke: incidence, impact, and implications for rehabilitation. Part I: classification and prevalence. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:752–760. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90038-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardie K, Hankey GJ, Jamrozik K, et al. Ten-year risk of first recurrent stroke and disability after first-ever stroke in the Perth community stroke study. Stroke. 2004;35:731–735. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000116183.50167.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teasell R, McCrae M, Foley N, et al. The incidence and consequences of falls in stroke patients during inpatient rehabilitation: factors associated with high risk. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:329–333. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.29623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamb SE, Ferruci L, Volapto S, et al. Risk factors for falling in home-dwelling older women with stroke. The women’s health and aging study. Stroke. 2003;34:494–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng PT, Liaw MY, Wong MK, et al. The sit-to-stand movement in stroke patients and its correlation with falling. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:1043–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorgensen L, Engstad T, Jacobsen BK. Higher incidence of falls in long-term stroke survivors than in population controls. Depressive symptoms predict falls after stroke. Stroke. 2002;33:542–547. doi: 10.1161/hs0202.102375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramnemark A, Nyberg L, Lorentzon R, et al. Progressive hemiosteoporosis on the paretic side and increased bone mineral density in the nonparetic arm the first year after severe stroke. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9:269–275. doi: 10.1007/s001980050147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorgensen L, Crabtree NJ, Reeve J, et al. Ambulatory level and asymmetrical weight bearing after stroke affects bone loss in the upper and lower part of femoral neck differently: bone adaptation after decreased mechanical loading. Bone. 2000;27:701–707. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramnemark A, Nyberg L, Borssen B, et al. Fractures after stroke. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:92–95. doi: 10.1007/s001980050053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ahmed S, et al. Disablement following stroke. Disability Rehabil. 1999;21:258–268. doi: 10.1080/096382899297684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rimmer JH. Health promotion for people with disabilities: the emerging paradigm shift from disability prevention to prevention of secondary conditions. Phys Ther. 1999;79:495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimmer JH, Riley B, Creviston T, et al. Exercise training in a predominantly African-American group of stroke survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:1990–1996. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200012000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dean CM, Shepherd RB. Task-related training improves performance of seated reaching tasks after stroke. A randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 1997;28:722–728. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.4.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teixeira-Salmela LF, Olney SJ, Nadeau S, et al. Muscle strengthening and physical conditioning to reduce impairment and disability in chronic stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1211–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macko RF, Smith GV, Dobrovolny L, et al. Treadmill training improves fitness reserve in chronic stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:879–884. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.23853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 1997;277:925–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly-Hayes M, Robertson JT, Broderick JP, et al. The American Heart Association Stroke Outcome Classification: Executive Summary. Circulation. 1998;97:2474–2478. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.24.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiat Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 6. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, et al. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:468–489. doi: 10.1007/s001980050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borg G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1970;2:92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Thoracic Society. ATS Statement: Guidelines for the Six-Minute Walk Test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eng JJ, Chu KS, Dawson AS, et al. Functional walk tests in individuals with stroke: relation to perceived exertion and myocardial exertion. Stroke. 2002;33:756–761. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.104195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohannon RW. Measurement and nature of muscle strength in patients with stroke. J Neuro Rehabil. 1997;11:115–25. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berg K, Maki BE, Williams JI, et al. Clinical and laboratory measures of postural balance in an elderly population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:1073–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Washburn RA, Zhu W, McAuley E, et al. The physical activity scale for individuals with physical disabilities: development and evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:193–200. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.27467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanis JA, Gluer C-C. An update on the diagnosis and assessment of osteoporosis with densitometry. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:192–202. doi: 10.1007/s001980050281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duncan P, Studenski S, Richards L, et al. Randomized clinical trial of therapeutic exercise in subacute stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:2173–2180. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000083699.95351.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeng C, Chang W, Wai PM, et al. Comparison of oxygen consumption in performing daily activities between patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a healthy population. Heart Lung. 2003;32:121–130. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2003.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lakka TA, Laukkanen J, Rauramaa R, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and the progression of carotid atherosclerosis in middle-aged men. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:12–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blair SN, Kohl HW, III, Barlow CE, et al. Changes in physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of health men and unhealthy men. JAMA. 1995;273:1093–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL, et al. The association of changes in physical-activity level and other lifestyle characteristics with mortality among men. N Eng J Med. 1993;328:538–545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swain DP, Franklin BA. VO2 reserve and the minimal intensity for improving cardiorespiratory fitness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:152–157. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200201000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pang MYC, Eng JJ, Dawson AS. Relationship between ambulatory capacity and cardiorespiratory fitness in chronic stroke. Influence of stroke-specific impairments. Chest. 2005;127:495–501. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.2.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamdy RC, Moore SW, Cancellaro VA, et al. Long-term effects of strokes on bone mass. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;74:351–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincent KR, Braith RW. Resistance exercise and bone turnover in elderly men and women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:17–23. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Welsh L, Rutherford OM. Hip bone mineral density is improved by high-impact aerobic exercise in postmenopausal women and men over 50 years. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1996;74:511–517. doi: 10.1007/BF02376766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frost HM. Absorptiometry and “osteoporosis”: problems. J Bone Miner Metab. 2003;21:255–260. doi: 10.1007/s00774-003-0418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner CH, Robling AG. Designing exercise regimens to increase bone strength. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2003;31:45–50. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vico L, Pouget JF, Calmels P, et al. The relations between physical ability and bone mass in women aged over 65 years. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:374–383. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mao H-F, Hsueh I-P, Tang P-F, et al. Analysis and comparison of the psychometric properties of three balance measures for stroke patients. Stroke. 2002;33:1022–1027. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000012516.63191.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]