Abstract

There is an increasing amount of literature data showing the positive effects on preclinical anti-Parkinsonian rodent models with selective positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGlu4).1 However, most of the data generated utilize compounds that have not been optimized for drug-like properties and, as a consequence, they exhibit poor pharmacokinetic properties and thus do not cross the blood-brain barrier. Herein, we report on a series of N-4-(2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl)-phenylpicolinamides with improved PK properties with excellent potency and selectivity as well as improved brain exposure in rodents. Finally, ML182 was shown to be orally active in the haloperidol induced catalepsy model, a well-established anti-Parkinsonian model.

Keywords: metabotropic glutamate receptors, mGlu4, positive allosteric modulators, Parkinson’s disease, haloperidol-induced catalepsy, structure-activity relationship (SAR), oral efficacy, brain penetration

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease that affects the central nervous system and is present in nearly 1 in 300 adults.1 With the exception of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), PD is the most common neurodegenerative disorder. PD is part of a larger group of conditions known as movement disorders and is characterized by four major primary symptoms: tremor, which is present at rest; bradykinesia, loss of spontaneous movement; rigidity, an increase in muscle tone; and disturbance of posture, an inability to maintain an upright posture.1–4 The major motor disturbances in PD patients are due to the loss of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra which results in the decreased stimulation of the motor cortex by the basal ganglia. In addition to the more prominent motor disturbances, PD patients also suffer from significant non-motor symptoms, such as depression, sleep disorders, and cognitive problems.1–6 Although the disease was first noted in the medical community nearly 200 years ago7, there is still no known cure for PD – and, as important, there are very few palliative drugs that provide benefit over the time frame of the disease progression.

Due to the discovery that the loss of dopaminergic neurons is the primary culprit for the motor disturbances in PD patients, the development of dopamine (DA) replacement therapies have dominated the PD treatment landscape.8 The primary pharmaceutical used for the treatment of PD is levodopa (L-DOPA) – since the use of dopamine itself proved ineffective since it does not cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). However, it was also discovered that the use of L-DOPA as a stand-alone treatment proved very difficult due to the rapid decarboxylation of L-DOPA which releases vasoactive DA prior to crossing the BBB, resulting in severe cardiovascular events. This side effect can be mitigated by the co-administration of an amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor which significantly increases the levels of DA in the CNS without the cardiovascular side effects.3, 4 Several other direct-acting DA agonists have been introduced, as well other therapies for increasing DA levels. Although the introduction of L-DOPA has significantly improved the initial treatment of PD, DA-replacement therapies have significant complications with long-term use. For example, a ‘wearing-off’ and ‘on-off’ phenomenon has been noted in which DA-replacement therapies lose efficacy over time, resulting in an ever-increasing dosage cycle.9, 10 Other consequences of DA-replacement include dyskinesias (rocking movements, repetitive motor behaviors) and psychotic and behavioral disturbances that often develop after long-term usage.11 Due to these significant side-effects of DA-replacement, alternative approaches towards the treatment and reversal of PD have been investigated, including invasive surgery and deep brain stimulation (DBS), along with attempts to develop agents to manipulate other, potentially druggable targets (e.g., antagonists of A2A adenosine receptors). Due to the limitations of current therapies for PD, we became interested in a potentially new target for the palliative care, and potential disease-modification, of PD. Due to exceptionally high expression levels of metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGlu4) at the striatopallidal synapse of the basal ganglia, we and others have targeted this receptor for therapeutic intervention into PD.12–17

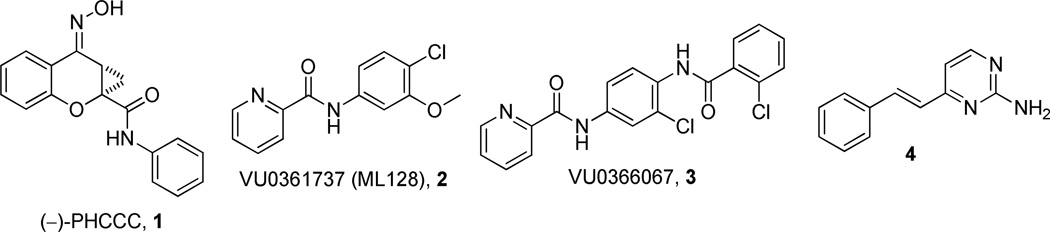

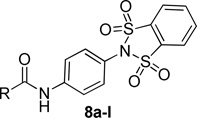

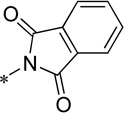

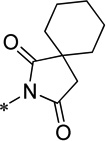

Over the past several years, our laboratories and others have added to the list of selective and novel tool compounds for the study of mGlu4 via positive allosteric modulation (Figure 1). Thus far, three disclosed mGlu4 PAMs (218, 319 and 420) have been shown to be CNS penetrant when dosed systemically, with compound 4 exhibiting efficacy in the haloperidol-induced catalepsy assay.21 In addition to the aforementioned in vivo tool compounds, there have been numerous in vitro tools reported.22–24

Figure 1.

Structures of recently reported mGlu4 PAMs.

Compound 3 possesses an acceptable balance of in vitro pharmacological properties, as well as moderate stability in rat liver microsomes (RLM). While compound 3 was able to cross the blood-brain barrier with an acceptable brain:plasma ratio (B/P = 1), its overall brain penetration was substantially reduced compared to the aminopyridine, 4. In this study, we disclose a series of N-4-(2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl)-phenylpicolinamide mGlu4 positive allosteric modulators that are CNS penetrant and show oral efficacy in an anti-Parkinsonian animal model.

Results and Discussion

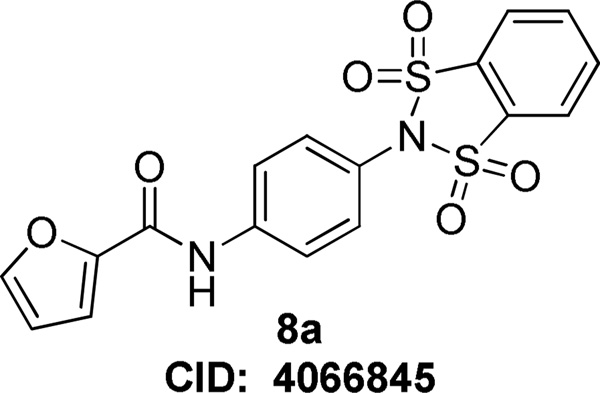

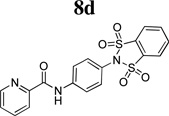

Although we have reported on several mGlu4 in vitro and in vivo tool compounds, there still remains room for significant improvement in an acceptable probe for the mGlu4 receptor. To this end, we started from a functional high-throughput screening (HTS) initiated at Vanderbilt University, and discovered an interesting new lead compound, N-(4-(1,1,3,3-tetraoxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazol-2-yl)phenyl)furan-2-carboxamide, 8 (Figure 2, Pubchem Compound ID (CID): 4066845; ChemDiv ID: K906-0087). Although compound 8 did not possess favorable calculated properties for a CNS probe compound (MW = 404.4, TPSA = 109.9), it represented a submicromolar starting point for our mGlu4 hit-to-lead program.

Figure 2.

Structure of initial HTS hit.

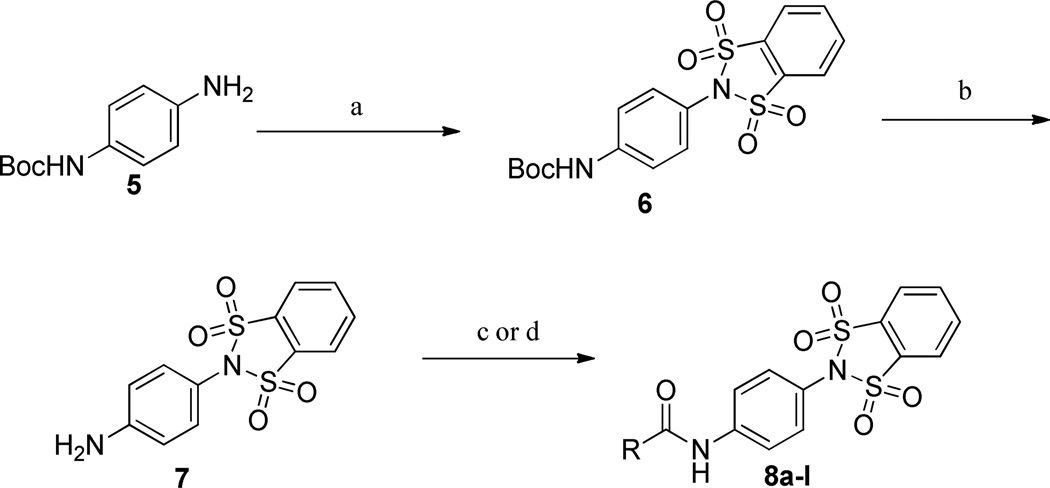

The 1,1,3,3-tetraoxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazol-2-yl)phenyl)carboxamide compounds were synthesized as outlined in Scheme 1. Commercially available mono-Boc protected 1,4-dianiline, 5, was reacted with 1,2-dibenzenedisulfonyl dichloride (Et3N, CH2Cl2) yielding 6. Next, the Boc group was removed under acidic conditions (4.0 M HCl/dioxane) and then the amides, 8a–l, were formed utilizing either the carboxylic acids (EDCI, HOBt, dioxane/DMF) or acid chlorides (DIEA, CH2Cl2).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 1,1,3,3-tetraoxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazol-2-yl)phenyl)carboxamides, 8a–l.

a Reagents and conditions: (a) 1,2-benzenedisulfonyl dichloride, Et3N, CH2Cl2; (b) 4.0 M HCl/dioxane, 99% (2 steps); (c) RCOCl, CH2Cl2, DIEA, 49–87%; (d) RCO2H, EDCI, HOBt, dioxane/DMF, 27–74%. All library compounds were purified by mass-directed prep LC with a purity of >95%.

The structure-activity relationship (SAR) surrounding this set of compounds mirrored other series that we have reported previously (Table 1).18, 19, 24 Namely, the 2-pyridyl amide, 8d, was the most potent heterocyclic substituent (hEC50 = 136 nM). Other aryl, cycloalkyl and 5-membered heterocycles also showed submicromolar potency at both the human and rat mGlu4 receptors. However, despite these modifications, the molecular weight (MW) and polar surface area (TPSA) remained suboptimal for the design of a CNS penetrant probe compound. To confirm this prediction, we profiled 8d in both in vitro and in vivo rat pharmacokinetic (PK) experiments and assessed the extent of CNS penetration for this compound (Table 2). While the compound displayed selectivity against other mGlu subtypes (mGlu1–3,5,6–8), the extent of brain penetration was poor (B/P = 0.085) following intraperitoneal (IP) administration to rats‥

Table 1.

Human mGlu4 potency and %GluMax response (as normalized to standard 1) for selected western amide analogs.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | R | hEC50 (nM)a | GluMax (%1)a | tPSA | cLogP |

| 8a | 2-furan | 226 ± 61 | 110.3 ± 5.8 | 109.9 | 1.77 |

| 8b | phenyl | 402 ± 74 | 65 ± 1.5 | 100.6 | 2.60 |

| 8c | cyclohexyl | 765 ± 133 | 48.3 ± 3.3 | 100.6 | 3.14 |

| 8d | 2-pyridyl | 136 ± 61 | 99.7 ± 0.9 | 113.0 | 2.19 |

| 8e | 3-pyridyl | Inactiveb | 27.7 ± 2.7 | 113.0 | 1.84 |

| 8f | 4-pyridyl | Inactiveb | 22.3 ± 1.9 | 113.0 | 1.84 |

| 8g | 6-fluoro-2-pyridyl | 1800 ± 1500 | 76.7 ± 8.1 | 113.0 | 2.42 |

| 8h | 6-methoxy-2-pyridyl | Inactiveb | 22.0 ± 1.2 | 122.2 | 2.64 |

| 8i | 4-pyrimidine | 179 ± 36 | 100.3 ± 4.9 | 125.3 | 1.41 |

| 8j | 2-thiazole | 353 ± 125 | 122.3 ± 5.9 | 113.0 | 2.05 |

| 8k | 4-thiazole | 104 ± 34 | 123 ± 1.2 | 113.0 | 2.05 |

| 8l | 5-thiazole | Inactiveb | 39.7 ± 0.3 | 113.0 | 2.05 |

EC50 and maximal response when compared to glutamate (GluMax) are the average of at least three independent determinations performed in triplicate (Mean ± SEM). 1 is run as a control compound each day, and the maximal response generated in human mGlu4 CHO cells in the presence of mGlu4 PAMs varies slightly in each experiment. Therefore, data were further normalized to the relative 1 response obtained in each day’s run.

Inactive compounds are defined as those in which the %GluMax did not surpass 2X the EC20 value for that day’s run.

Table 2.

Characteristics of previously reported mGlu4 tool compounds from Vanderbilt University.

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | |||

| MW | 262.7 | 386.2 | 414.5 |

| TPSA | 50.7 | 70.6 | 113.0 |

| cLogP | 2.80 | 2.74 | 2.19 |

| hmGlu4 EC50 (nM) | 240 ± 40 | 517 ± 57 | 136 ± 61 |

| rmGlu4 EC50 (nM) | 110 ± 30 | 570 ± 131 | 165 ± 1 |

| rmGlu4 CRC Fold Shift | 35.3 ± 2.8 | 18.3 ± 1.3 | 5.2 ± 0.6 |

| rat CLHEP (mL/min/kg) | 65.5 | 27.3 | ND |

| rPPB (%fu) | 2.4 | 0.29 | 3.8 |

| CYP (1A2, 2C9, 3A4, 2D6) µM | <0.1, >30, >30, >30 | >30, 11.8, >30, 13.1 | >30 |

| mGlu selectivity | 5.1 µM (5), 2.7 FS (8) | 5.3 FS (7), 3.8 FS (8) | selective |

| B/P | 4.1 | 1.04 | 0.085 |

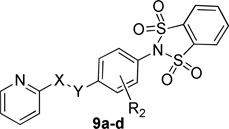

Next, we turned our attention to compounds that would have more favorable calculated properties for a CNS penetrant molecule (MW < 400, TPSA < 90) (Table 3). To this end we examined the effect of removing the carbonyl of the amide was evaluated. Subsequent replacement of the carbonyl with a methylene group (9b) or a cyclopropyl group (9c) effectively reduced the TPSA (113 to 96) of the scaffold, however with a cost of 10- to 40-fold reduction in mGlu4 potency. Likewise, the addition of a substituent ortho to the amide on the internal phenyl group (9a), or reversing the amide (9d), proved to alter the TPSA but, again, with a significant reduction in the potency for both compounds.

Table 3.

Human mGlu4 potency and efficacy (as normalized to standard 1) for bis-sulfonamide scaffold modifications.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | X | Y | R2 | hEC50 (nM)a | GluMax (%1)a | tPSA | cLogP |

| 9a | CO | NH | 2-F | 1100 ± 424 | 67.7 ± 2.7 | 113 | 1.89 |

| 9b | CH2 | NH | H | 1800 ± 199 | 110.0 ± 6.2 | 95.9 | 1.54 |

| 9c | cyclopropyl | NH | H | 6400 ± 750 | 62.7 ± 8.4 | 95.9 | 1.88 |

| 9d | NH | CO | H | Inactiveb | 30.7 ± 2.4 | 113 | 2.19 |

EC50 and maximal response when compared to glutamate (GluMax) are the average of at least three independent determinations performed in triplicate (Mean ± SEM). 1 is run as a control compound each day, and the maximal response generated in human mGlu4 CHO cells in the presence of mGlu4 PAMs varies slightly in each experiment. Therefore, data were further normalized to the relative 1 response obtained in each day’s run.

Inactive compounds are defined as those in which the %GluMax did not surpass 2X the EC20 value for that day’s run.

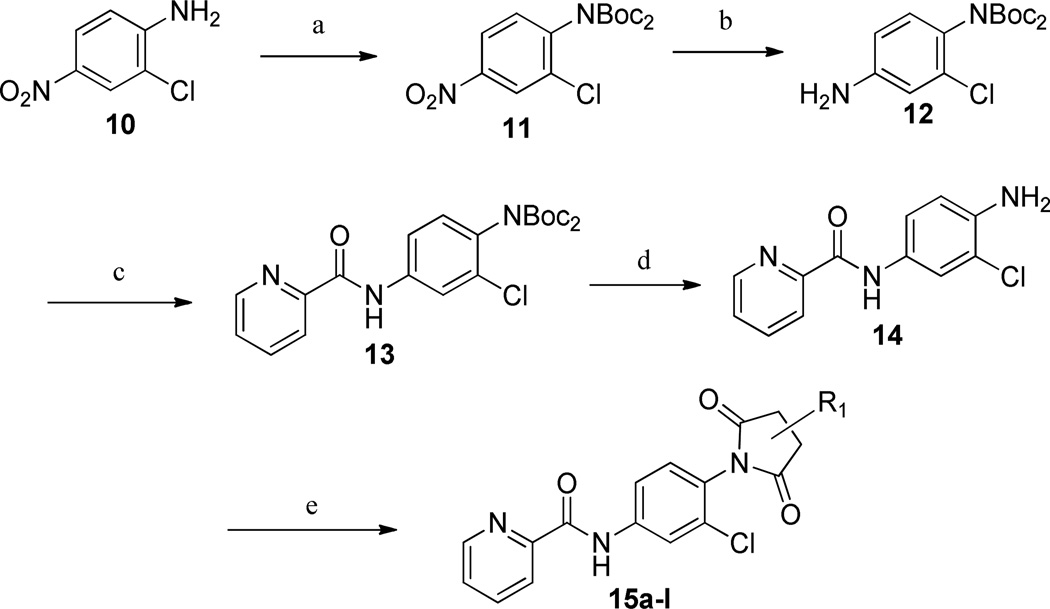

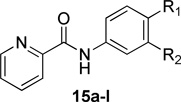

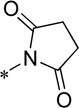

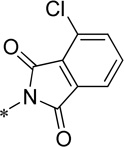

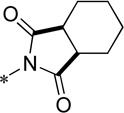

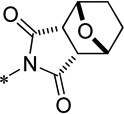

One area of diversification where we have had success with other series is the 4-position of the internal phenyl group. Therefore, we evaluated the activity of a number of substitutions similar to the 1,1,3,3-tetraoxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazol-2-yl group, in an attempt to reduce TPSA and, ultimately, improve brain penetration. The inclusion of an imide group in lieu of the 1,1,3,3-tetraoxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazol-2-yl moiety represented a net lowering of the MW by 60 Da and the TPSA by approximately 30 Å2. The synthesis of the imide compounds is shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of N-4-(2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl)-phenylpicolinamides.’a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) Boc2O, DMAP, THF, reflux, 99%; (b) Pd/C, EtOAc, H2 (1 atm), rt; (c) Picolinoyl chloride HCl, CH2Cl2, pyridine, 84%; (d) 4.0 HCl/dioxane; (e) anhydride, toluene:AcOH (3:1), µW, 150 °C, 90 min. All library compounds were purified by mass-directed prep LC with a purity of >95%.

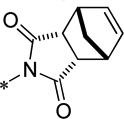

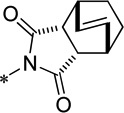

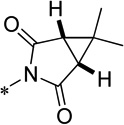

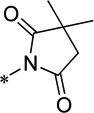

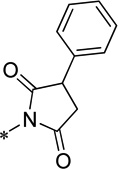

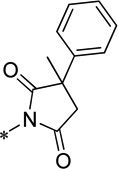

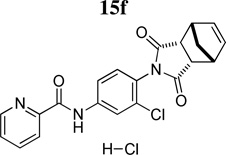

Evaluation of the compound containing a sultam group revealed a complete loss of activity (16) (Table 4). This core phenyl group does not contain a halogen as do the other compounds; however, the compound containing an internal halogen was not attainable by synthesis. Next, a series of imide compounds were investigated. The initial five-membered imide compound was active (15a, hEC50 = 6200 nM), however the compound lost ~20-fold activity compared to 8d. Potency could be recovered by increasing the bulk of the right-hand side by utilizing phthalimide (and substituted phthalimides) (15b, hEC50 = 59.4 nM; 15c, hEC50 = 42 nM). However, an initial metabolic stability assessment revealed these compounds suffered from extensive oxidative metabolism (results not shown). Having demonstrated the phenyl moiety of the phthalimide as the predominant metabolic soft spot, we turned to saturated versions of the phthalimide (15d – 15l). The initial compound was the direct saturated comparator to 15b (15d, hEC50 = 370 nM). Although there was a ~10-fold loss of potency, 15d still showed <500 nM potency against hmGlu4. The trans-isomer was also evaluated with similar potency to the cis-15d (results not shown). Increasing the bulk of the saturated six-membered ring resulted in interesting compounds. The [2.2.1]-bridged oxo compound (15e, hEC50 = 1300 nM) exhibited a 4-fold loss in potency; however the unsaturated [2.2.1]-bridged carbon analog (15f, hEC50 = 291 nM) and unsaturated [2.2.2]-analog (15g, hEC50 = 287 nM) were more potent than 15d. Reducing the ring size from 6-membered to a substituted 3-membered ring resulted in an equipotent compound (15h, hEC50 = 435 nM). Substitution of the 5-membered imide led to a loss of activity (15i, hEC50 = 1400 nM), but remained comparable to the initial 5-membered imide (15a). However, when the size of the substituent was increased from the gem-dimethyl to cyclohexyl (15j, hEC50 = 158 nM) there was a 10-fold increase in activity. Other bulky substituents were evaluated (15k, hEC50 = 674 nM; 15l, hEC50 = 771 nM); however, these compounds lost activity when compared to 15f.

Table 4.

Human mGlu4 potency and efficacy (as normalized to standard 1) for selected bis-sulfonamide replacements.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | R1 | R2 | hEC50 (nM) | GluMax (%1) | tPSA | cLogP |

| 16 |  |

H | Inactive | 25.0 ± 2.5 | 78.8 | 1.12 |

| 15a |  |

Cl | 6200 ± 1700 | 74.0 ± 4.5 | 78.8 | 0.69 |

| 15b |  |

Cl | 59.4 ± 7.9 | 103.7 ± 1.2 | 78.8 | 3.12 |

| 15c |  |

Cl | 41.9 ± 5.4 | 130.3 ± 3.4 | 78.8 | 3.86 |

| 15d |  |

Cl | 370 ± 23 | 107.0 ± 4.5 | 78.8 | 2.12 |

| 15e |  |

Cl | 1300 ± 180 | 90.0 ± 1.7 | 88.1 | 1.03 |

| 15f |  |

Cl | 291 ± 55 | 122.3 ± 1.5 | 78.8 | 1.91 |

| 15g |  |

Cl | 287 ± 62 | 120.3 ± 5.9 | 78.8 | 2.47 |

| 15h |  |

Cl | 435 ± 118 | 100.3 ± 2.9 | 78.8 | 0.96 |

| 15i |  |

Cl | 1400 ± 214 | 82.0 ± 3.5 | 78.8 | 1.73 |

| 15j |  |

Cl | 158 ± 20 | 78.7 ± 4.2 | 78.8 | 2.68 |

| 15k |  |

Cl | 674 ± 153 | 116.7 ± 8.3 | 78.8 | 2.45 |

| 15l |  |

Cl | 771 ± 126 | 123.7 ± 3.5 | 78.8 | 2.97 |

EC50 and maximal response when compared to glutamate (GluMax) are the average of at least three independent determinations performed in triplicate (Mean ± SEM). 1 is run as a control compound each day, and the maximal response generated in human mGlu4 CHO cells in the presence of mGlu4 PAMs varies slightly in each experiment. Therefore, data were further normalized to the relative 1 response obtained in each day’s run.

Inactive compounds are defined as those in which the %GluMax did not surpass 2X the EC20 value for that day’s run.

With our best compounds evaluated for human potency, we evaluated the in vitro potency of the compounds on the rat mGlu4 receptor. Additionally, we compared compounds in terms of their relative efficacy which we evaluated by assessing the ability of a 30 µM concentration of each compound to shift a glutamate concentration-response curve to the left (represented as fold shift, FS) (Table 5). For examination of compound activity at the rat receptor, we employ an assay in which we measure the ability of the Gi/o-coupled mGlu4 receptor to couple to G Protein Inwardly Rectifying Potassium (GIRK) channels.25 In contrast to the calcium mobilization assay, we generally do not observe large increases above the response elicited by saturating concentrations of glutamate alone when GIRK activation is used to assess activity; rather, compounds shift the glutamate concentration-response curve to the left only. Compounds from the 1,1,3,3-tetraoxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazol-2-yl)phenyl)carboxamide series (8d–8k) all possessed GluMax values comparable to that of 1 and their efficacies in shifting the glutamate curve were modest, between 3.3 and 7.3. However, moving from the 1,1,3,3-tetraoxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazol-2-yl)phenyl)carboxamide series to the imide series produced significant divergence in compound efficacies. In particular, two phthalimide compounds (15b and 15c) exhibited large differences in efficacy (leftward fold shift values of 23.6 and 83.0, respectively). Compound 15c produced the largest leftward shift of the glutamate response curve reported to date. It is also noted that moving away from the phthalimide structures to the saturated imides led to a significant reduction in efficacy and the largest fold shift value for the saturated compounds was 16.7 (15l), with most of the compounds tested exhibiting fold shifts of <10 (See Supplemental Figure 1 for graphs of human and rat potency and fold shift experiments). The exceptions were 15f (11.2), 15k (12.1) and 15l (16.7).

Table 5.

Rat mGlu4 receptor potency and efficacy (fold shift) data for selected compounds.

| Cmpd | EC50 (nM)a | GluMaxa | Fold Shift |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8d | 165 ± 1 | 124.3 ± 3.6 | 5.2 ± 0.6 |

| 8i | 242 ± 36 | 103.3 ± 3.2 | 3.3 ± 0.3 |

| 8j | 201 ± 37 | 127.1 ± 4.5 | 4.7 ± 0.4 |

| 8k | 105 ± 15 | 115.2 ± 2.3 | 7.3 ± 0.8 |

| 15b | 66.8 ± 4 | 131.8 ± 3.9 | 23.6 ± 3.1 |

| 15c | 34.9 ± 5.2 | 137.4 ± 3.2 | 83.0 ± 16.8 |

| 15d | 645 ± 63 | 129.1 ± 2.8 | 8.3 ± 0.5 |

| 15f | 376 ± 23 | 120.3 ± 3.2 | 11.2 ± 0.8 |

| 15g | 246 ± 12 | 122.2 ± 4.5 | 5.2 ± 1.2 |

| 15h | 686 ± 32 | 105.1 ± 0.1 | 5.5 ± 0.5 |

| 15j | 397 ± 38 | 114.2 ± 1.5 | 4.8 ± 0.2 |

| 15k | 491 ± 57 | 137.8 ± 2.0 | 12.1 ± 1.0 |

| 15l | 536 ± 105 | 130.7 ± 3.9 | 16.7 ± 1.7 |

EC50 and maximal response when compared to glutamate (GluMax) are the average of at least three independent determinations performed in triplicate (Mean ± SEM).

Having identified several key compounds based on human and rat potency as well as efficacy at the rat receptor, we evaluated these compounds in a battery of pharmacokinetic assays including an assessment of intrinsic clearance (CLint) in hepatic microsomes. In addition to intrinsic clearance allowing for the prediction of pertinent rat and human PK parameters (CL and t1/2), intrinsic clearance assessments allow for a rank ordering of compounds with respect to oxidative lability and a subsequent predicted stability in our in vivo PK and efficacy models (Table 6). Although two compounds based on the phthalimide scaffold (15b and 15c) showed excellent in vitro potency on mGlu4, these compounds have been previously reported by Merck and thus were not further evaluated.26 The three compounds based on the saturated imide scaffold (15f, 15j–k) displayed elevated clearance in human liver microsomes, each exceeding hepatic blood flow in humans (QH, 21 mL/min/kg). Conversely, an assessment in RLM indicated the compounds to possess moderate-to-high predicted hepatic clearance (CLHEP), with compound 15k predicting the best stability in rat (CLHEP = 30 mL/min/kg). Assessment of the compound’s affinity for plasma proteins was also estimated (percent free, unbound; %fu) in vitro in cryopreserved plasma (Table 6). While compounds 15j and 15k were highly protein bound in both human and rat plasma (%fu <1), 15f displayed lower protein binding under the same conditions (%fu >3). In addition, 15f was also investigated for nonspecific binding (NSB) in freshly prepared rat brain homogenate employing rapid equilibrium dialysis and found to display a decrease in NSB (%fu >7%) relative to binding to plasma proteins. As a first-tier screen for potential drug-drug interaction liability, the compounds were evaluated for their inhibition of the cytochrome P450 (CYP450 or CYP) enzymes utilizing a cocktail approach in human liver microsomes designed to inform on the inhibition of the five major drug-metabolizing and/or polymorphic CYPs (CYP2C9, 2D6, 3A4, 2C19, and 1A2). All compounds tested showed no significant activity against CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 (>30 µM); and only 15k showed moderate inhibition of 2C9, 2C19 and 1A2 (8.7 µM, 17.6 µM, and 8.9 µM, respectively).

Table 6.

Predicted hepatic clearance, plasma protein binding, CYP450 inhibition, and mGlu selectivity values for selected compounds

| 15f | 15j | 15k | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Intrinsic Clearance (mL/min/kg) | |||

| Human CLHEP | 19.7 | 19.4 | 19.9 |

| Rat CLHEP | 53.0 | 66.7 | 32.6 |

|

Plasma Protein Binding (PPB) | |||

| human (%fu) | 4.1 | 0.62 | 0.02 |

| rat (%fu) | 3.2 | 0.5 | 0.17 |

| BHB (rat, %fu) | 7.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 |

|

CYP450 IC50 (µM) | |||

| 2C9 | >30 | >30 | 8.7 |

| 2D6 | >30 | >30 | >30 |

| 3A4 | >30 | >30 | >30 |

| 2C19 | >30 | >30 | 17.6 |

| 1A2 | >30 | >30 | 8.9 |

|

mGlu Selectivitya | |||

| mGlu1,2,3 | Inactiveb | Inactiveb | Inactiveb |

| mGlu5 | PAM, 2.1 FS | Inactiveb | PAM 2.0 FS |

| mGlu6 | PAM, 3.1 FS | PAM, 2.1 FS | PAM, 5.8 FS |

| mGlu7 | PAM, 2.9 FS | Inactiveb | Ago-PAM, 12.9 FS |

| mGlu8 | Inactiveb | Inactiveb | PAM, 2.1 FS |

Selectivity was assessed by incubating cells with either DMSO-matched vehicle or a 10 µM final concentration of compound in the presence of a full glutamate (or, in the case of mGlu7, L-AP4) concentration-response curve. FS = fold shift of the glutamate concentration-response curve. Cmpd 15f showed weak potentiator activity on mGlu5, mGlu6 and mGlu7 (leftward shift of the glutamate concentration-response).

Inactive compounds showed no ability to left-shift the glutamate response curve at 10 µM. No antagonist activity was noted for any compound at any receptor tested.

Lastly, these compounds were evaluated for their selectivity against the other mGlu receptors. For initial studies, a 10 µM concentration of compound was applied prior to a complete agonist concentration-response curve (CRC) appropriate for each receptor. This technique allows for the detection of potentiator (leftward shift) or antagonist (rightward shift and/or decrease in the maximal response) activity within a single experiment. Using this assay, all compounds were selective versus the Group II mGlus (2 and 3) and only 15f showed weak PAM activity against a group I receptor (mGlu5, 2.1 FS). However, these compounds did show varying selectivity against the other Group III receptors. Whereas 15j only showed weak activity against mGlu6 (PAM, 2.1 leftward FS of the agonist CRC), 15f was weakly active against both mGlu6 (PAM, 3.1 FS) and mGlu7 (PAM, 2.9 FS), and 15k showed activity against all 3 receptors (mGlu6, PAM, 5.8 FS; mGlu7, mixed agonist/PAM (Ago-PAM) activity, 12.9 FS; mGlu8, PAM, 2.1 FS); the allosteric agonist activity against mGlu7 was equivalent to that observed for mGlu4 (12.9 FS vs. 12.1 FS).

The predicted in vitro ADME properties of these compounds were consistent with advancement for in vivo studies. Thus, the hydrochlorides of these compounds (15f, 15j, 15k) were synthesized and dosed intraveneously (1 mg/kg) and orally (10 mg/kg) to determine pertinent PK parameters such as clearance (CL), volume-of-distribution at steady state (Vss), half-life (t1/2) as well as bioavailability (%F) (Table 7). Although all three compounds displayed modest stability (CLHEP) when assessed in rat liver microsomes; 15k proved to be a lower clearance compound in vivo (5.4 mL/min/kg). Both 15f and 15j demonstrated moderate clearance values (37 mL/min/kg and 48 mL/min/kg, respectively), values that correlated well with their in vitro CLHEP values. Due to the exceptional stability of 15k following parenteral administration to the rat, we evaluated this compound in both beagle dog and rhesus monkey employing an IV cassette dosing paradigm. Compound 15k showed excellent stability in both dogs (CL, 7 mL/min/kg) and monkeys (3 mL/min/kg) with each species diplaying a t1/2 of ≥ 3 hrs. Although 15k showed superior stability comparatively, it unfortunately displayed an oral bioavailability less than 10%; Conversely, compound 15f demonstrated an excellent oral bioavailability of 97% whereas 15j displayed a modest bioavailability of 25%.

Table 7.

Rat in vivo pharmacokinetic values for selected compounds

| PK parameters (rat) | 15f | 15j | 15k |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV (1 mg/kg)a | |||

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 36.9 | 48.3 | 5.4 |

| t½ (min) | 40.4 | 93.8 | 329 |

| MRT | 493 | 57.2 | 109 |

| Vss (L/kg) | 18 | 5.5 | 0.58 |

| AUC0–24 (ng*hr/mL) | 454 | 346 | 3225 |

| PO dose (10 mg/kg)b | |||

| AUC0–24 (h*ng/mL) | 4354 | 813 | 2685 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 238 | 18.3 | 553 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.62 | 7 | 0.5 |

| %F | 97 | 24.6 | 8.3 |

10% EtOH, 80% PEG-400, 10% saline.

10% Tween 80 in 0.5% methylcellulose.

The combination of enhanced bioavailability, oral PK, in addition to an exceptionally low protein binding value, indicated that compound 15f possessed the characteristics to be a potential tool compound which could be evaluated for brain exposure after oral dosing (Table 8). The hydrochloride salt of 15f was dosed orally in a microsuspension (10% Tween-80 in 0.5% methylcellulose) and plasma (systemic and hepatic portal) and brain samples were collected for bioanalysis of parent compound up to 6 hours following administration of the compound. The compound showed similar levels in the systemic and HPV plasma, indicating neglible hepatic first pass metabolism (AUCSYS/AUCHPV = 1.01). Compound 15f also displayed exceptional CNS penetration, with compound exposures reaching 800 nM*h (AUC0–6) and a corresponding brain:plasma ratio that reached unity (0.93).

Table 8.

PO pharmacokinetic parameters of 15f, (10 mg/kg, 10% Tween 80 in 0.5% methylcellulose).

| |

|---|---|

| PK Parameter - AUC, 0 – 6 ha | nM·h |

| Systemic | 858 |

| HPV | 848 |

| Brain | 800 |

| AUCbrain/AUCsys | 0.93 |

| AUCsys/AUCHPV | 1.01 |

PO dose, vehicle: 10 mg/kg, 10% Tween 80 in 0.5% methylcellulose

Considering the promising PK results for 15f, we evaluated the compound for selectivity against the other mGlu subtypes. In these studies, a 10 point concentration-response of 15f was applied prior to an EC20 concentration of agonist appropriate for each receptor. As with our original fold shift-type studies, 15f was shown to be inactive against mGlu 1, 2, 3, and 8 and was active against mGlu5 (PAM, EC50 = 1.7±0.8 µM, 64.3±0.8% GluMax), mGlu6 (PAM, EC50>10 µM, 45.8±3.0% GluMax) and mGlu7 (PAM, 2.9±0.7 µM, 64.0±1.4% GluMax) (See Supplemental Table 1). In addition, 15f was tested in Ricerca’s Lead Profiling Screen (binding assay panel of 68 GPCRs, ion channels and transporters screened at 10 µM), and was found to not significantly with all the 68 assays conducted (no inhibition of radioligand binding > 50% at 10 µM).

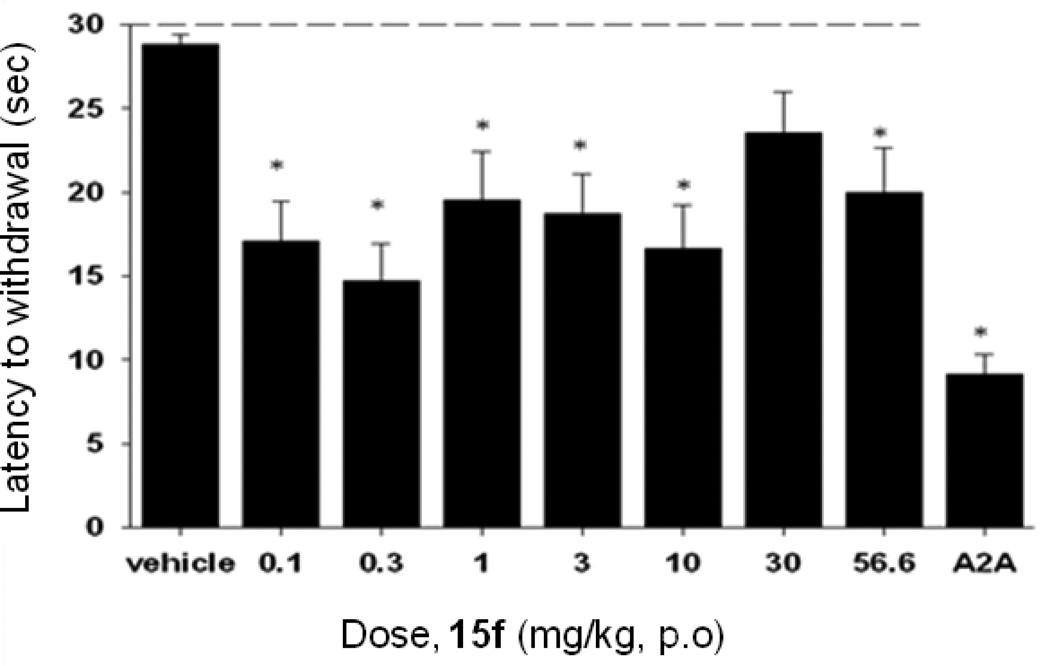

Based on the previous PK studies, 15f was chosen as a potential tool compound for an in vivo proof-of-concept study and was examined in a rat model of neuroleptic-induced catalepsy. Here we evaluated the ability of 15f to reverse haloperidol-induced catalepsy, a preclinical rodent model of motor impairments associated with Parkinson’s disease. The D2 receptor antagonist haloperidol induced robust catalepsy (Figure 10). As shown in Figure 10, 15f (0.1 – 56.6 mg/kg, p.o.) produced a reversal of haloperidol-induced catalepsy (F(8,89)= 5.8697, p<0.0001), significant at doses of 0.1 – 56.6 mg/kg, as compared with the vehicle control. The effects of 15f were equally efficacious to those observed using an adenosine A2A antagonist from Neurocrine Bioscience (compound 23)27 as a positive control, administered at a dose of 56.6 mg/kg, po.

Figure 10.

Reversal of haloperidol-induced catalepsy in rats by compounds 15f after oral dosing. Catalepsy was measured in haloperidol treated (0.75 mg/kg) rats after oral administration of compound (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30 and 56.6 mg/kg) after 30 mins. An adenosine A2A antagonist from Neurocrine Biosciences27 was used as a positive control at 56.6 mg/kg, po.

Conclusion

In summary, we have discovered and characterized a new mGlu4 PAM in vivo tool compound with activity in a preclinical model of Parkinson’s disease. This new class of N-4-(2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl)-phenylpicolinamides (such as 15f, VU0400195 (ML182))28 was discovered utilizing a rational drug design approach based on the 1,1,3,3-tetraoxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazol-2-yl)phenyl)carboxamides (8d) scaffold that possessed suboptimal properties. A common feature in many of the reported mGlu4 PAMs is the presence of a picolinamide moiety which this new scaffold also possesses. However, these new compounds are structurally distinct from previously reported structures due to the presence of the 2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl moiety. The present report represents only the second example of a potent and selective, orally active mGlu4 PAM.20

Experimental Section

General

All NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz AMX Bruker NMR spectrometer. 1H chemical shifts are reported in δ values in ppm downfield with the deuterated solvent as the internal standard. Data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, br = broad, m = multiplet), integration, coupling constant (Hz). Low resolution mass spectra were obtained on an Agilent 1200 series 6130 mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization. High resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Waters Q-TOF API-US plus Acquity system with electrospray ionization. Analytical thin layer chromatography was performed on EM Reagent 0.25 mm silica gel 60-F plates. All samples were of ≥95% purity as analyzed by LC-UV/Vis-MS. Analytical HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1200 series with UV detection at 214 nm and 254 nm along with ELSD detection. LC/MS: Method 1 = (J-Sphere80-C18, 3.0 × 50 mm, 4.1 min gradient, 5%[0.05%TFA/CH3CN]:95%[0.05%TFA/H2O] to 100%[0.05%TFA/CH3CN]; Method 2 = (Phenomenex-C18, 2.1 X 30 mm, 2 min gradient, 7%[0.1%TFA/CH3CN]:93%[0.1%TFA/H2O] to 100%[0.1%TFA/CH3CN]; Method 3 = (Phenomenex-C18, 2.1 X 30 mm, 1 min gradient, 7%[0.1%TFA/CH3CN]:93%[0.1%TFA/H2O] to 95%[0.1%TFA/CH3CN]. Preparative purification was performed on a custom HP1100 purification system (reference 16) with collection triggered by mass detection. Solvents for extraction, washing and chromatography were HPLC grade. All reagents were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. and were used without purification.

tert-Butyl (4-(1,1,3,3-tetraoxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazol-2-yl)phenyl)carbamate (6)

A solution of N-Boc-p-phenylenediamine, 5, (0.68 g, 3.26 mmol, 1.0 equivalents) and Et3N (0.51 mL, 7.19 mmol, 2.2 equivalents) in dry DCM (29 mL) was added via syringe pump (8 mL/ h) to a refluxing solution of 1,2-benzenedisulfonyl dichloride (0.90 g, 3.27 mmol, 1.005 equivalents) in DCM (135 mL). After the complete addition, the reaction solution was maintained at reflux for an additional 2 h. The heat was removed and after 16 h at rt, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue of the crude reaction mixture was redissolved in DCM (75 mL) and washed with saturated NaHCO3 (aq, 75 mL), brine (75 mL), and dried (MgSO4). After the filtration and concentration under reduced pressure, analytical LCMS confirms product (6). The material was taken through to the deprotection step. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.11-8.08 (m, 2 H), 7.99-7.96 (m, 2 H), 7.59-7.55 (m, 4 H), 6.66 (br s, 1 H), 1.54 (s, 9 H).

2-(4-Aminophenyl)benzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazole 1,1,3,3-tetraoxide (7)

To a solution of 6 (3.26 mmol, 1.0 equivalents) in DCM (100 mL) at 0 °C was added dropwise 4N HCl in dioxane (20 mL). After 15 min, the ice bath was removed. Once the starting material was no longer evident by TLC, the solvent was removed affording the HCl salt (7), which were taken through to the amide formation step. LCMS: RT = 3.319 min, m/z = 311.0 [M + H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) ° 8.55-8.51 (m, 2 H), 8.21-8.17 (m, 2 H), 7.17-7.15 (m, 2 H), 6.75-6.73 (m, 2 H).

N-(4-(1,1,3,3-Tetraoxidobenzo[d][1,3,2]dithiazol-2-yl)phenyl)picolinamide (8d)

To a solution of the HCl salt (7) (1.0 equivalent) in DCM:DIEA (4:1) (1 mL, 0.1 M) was added picolinyl acid chloride (1.0 equivalent) was added and after 12 h at rt, the desired analog, 8d, was obtained as an tan solid (49%). Analytical LCMS: RT = 3.074 min, >98% (214 nm), m/z = 416.1 [M + H]+; 1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO): δ 11.08 (br s, 1 H), 8.79 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz), 8.60-8.59 (m, 2 H), 8.24-8.21 (m, 5 H), 8.11 (t, 1 H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.73 (t, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 7.59 (d, 2 H, J = 8.4 Hz); 13C NMR (125 MHz, d-DMSO-d6) δ 163.5, 149.8, 148.9, 142.1, 138.7, 136.8, 134.0, 133.0, 127.7, 123.8, 123.1, 122.4, 119.1. HRMS, calc’d for C18H13N3O5NaS2 [M + Na+], 438.0194; found 438.0194.

Bis(tert-butyl-2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl)carbamate (11)

To a solution of 2-chloro-4-nitroaniline, 10, (5.0 g, 29 mmol) and DMAP (50 mg, 0.41 mmol) in dry THF (250 mL) was added Boc2O (16.0 g, 73.3 mmol). The mixture was heated to reflux. After 1h, the solvent was removed. The residue was redissolved in EtOAc:0.5 N HCl (aqueous) and the organic layer was separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 50 mL) and the collected organic layers were washed with Brine (100 mL). The solution was dried (MgSO4), filtered and concentrated to afford bis(tert-butyl-2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl)carbamate, 11. LCMS: RT = 3.74 min., >98% @ 254 nM, m/z = 767.2 [2M + Na]+.

Bis(tert-butyl-4-amino-2-chlorophenyl)carbamate (12)

To a solution of bis(tert-butyl-2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl)carbamate, 11, (29.0 mmol) in EtOAc (120 mL) was added 5% Pd/C (150 mg) and an H2 atmosphere was applied. After 12 h, TLC confirmed loss of starting material. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite and concentrated to afford bis(tert-butyl-4-amino-2-chlorophenyl)carbamate which was used without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.94 (d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.72 (d, 1 H, J = 2.8 Hz), 6.53 (dd, 1 H, J = 8.4, 2.8 Hz), 3.75 (br s, 2 H), 1.41 (s, 18 H).

Bis(tert-butyl 2-chloro-4-(picolinamido)phenyl)carbamate (13)

A solution of bis(tert-butyl-4-amino-2-chlorophenyl)carbamate, 12, (29.0 mmol) in DCM (25 mL) at 0 °C was subjected to DIEA (10.2 mL, 72.5 mmol) followed by picolinoyl chloride hydrochloride (5.68 g, 31.9 mmol). After 12 h, the reaction was added to EtOAc:H2O (1:1, 120 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (2 × 50 mL), brine (50 mL) and dried (MgSO4). The mixture was filtered and concentrated to provide bis(tert-butyl 2-chloro-4-(picolinamido)phenyl)carbamate, 13. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.17 (br s, 1 H), 8.63 (d, 1 H, J = 4.0 Hz), 8.32 (d, 1 H, J = 8.0), 8.05 (d, 1 H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.96 (ddd, 1 H, J = 8.0, 8.0, 1.2), 7.66 (dd, 1 H, J = 8.4, 2.4), 7.55-7.52 (m, 1 H), 7.20 (d, 1 H, J = 8.8 Hz), 1.40 (s, 18 H).

N-(4-Amino-3-chlorophenyl)picolinamide (14)

To a solution of bis(tert-butyl 2-chloro-4-(picolinamido)phenyl)carbamate, 13, (29.0 mmol) in DCM (300 mL) at 0 °C was added dropwise 4N HCl in dioxane (50 mL). After 15 min, the ice bath was removed. Once the starting material was no longer evident by TLC, the solvent was removed affording the HCl salt. The crude material was redissolved with EtOAc (100 mL) and washed with NaHCO3 (aqueous). The organic layer was dried (MgSO4), filtered and concentrated to afford N-(4-amino-3-chlorophenyl)picolinamide, 14. LCMS: RT = 1.15 min., >98% @ 254 nM, m/z = 248.0 [M + H]+.

General Cyclic Imide formation

To a solution of N-(4-amino-3-chlorophenyl)picolinamide, 14, (1.0 equivalent) in toluene:acetic acid (3:1) was added desired anhydride (1.25 equivalents) and the mixture was heated to 150 °C in the microwave for 90 min. After LCMS confirmed the product, the rxn was added to EtOAc:NaHCO3 (sat’d) (1:1) and the organic layer was separated, washed with Brine and dried (MgSO4). After the organic layer was filtered and concentrated, the material was purified by LC purification (Gilson) or crystallization.

N-(3-Chloro-4-((1R,2S,3R,4S-bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-1,3-dioxo-1H-isoindol-1-yl)phenyl) picolinamide (15f)

Following the general procedure, N-(3-Chloro-4-((1R,2S,3R,4S-bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-1,3-dioxo-1H-isoindol-1-yl) phenyl)picolinamide was obtained (mixture of diastereomers). LCMS: RT = 1.367 min, >98% @ 254 nM, m/z = 394.0 [M + H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.81 (d, 1 H, J = 4.4 Hz), 8.40 (s, 1 H), 8.31-8.28 (m, 1 H), 8.20 (d, 1 H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.84 (m, 1 H), 7.79 (d, 1 H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.05 (d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.31 (s, 2 H), 3.61-3.56 (m, 2 H), 3.44-3.42 (m, 2 H), 1.79-1.76 (m, 1 H), 1.71-1.68 (m, 1 H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, d-DMSO-d6, mixture of diastereomers) δ 176.5, 176.4, 163.44, 163.42, 149.8, 149.7, 148.9, 140.7, 140.4, 138.7, 135.3, 135.0, 131.7, 131.2, 130.6, 127.7, 126.0, 125.6, 123.1, 121.34, 121.31, 120.2, 119.9, 52.4, 52.1, 46.9, 45.7, 45.3, 44.9. HRMS, calc’d for C21H17N3O3Cl [M + H]+, 394.0958; found 394.0959.

N-(3-Chloro-4-(1,3-dioxo-2-azaspiro[4.5]decan-2-yl)phenyl)picolinamide (15j)

Following the general procedure, N-(3-chloro-4-(1,3-dioxo-2-azaspiro[4.5]decan-2-yl)phenyl)picolinamide was obtained. LCMS: RT = 1.439 min, >98% @ 254 nM, m/z = 398.2 [M + H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, d-DMSO-d6) δ 11.01 (br s, 1 H), 8.76 (d, 1 H, J = 4.4 Hz), 8.24 (d, 1 H, J = 2.0 Hz), 8.17 (d, 1 H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.08 (ddd, 1 H, J = 8.0, 8.0, 2.0 Hz), 7.99 (dd, 1 H, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz), 7.70 (ddd, 1 H, J = 7.6, 4.8, 1.2 Hz), 7.39 (d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 2.86 (d, 1 H, J = 18.0 Hz), 2.78 (d, 1 H, J = 18.4 Hz), 1.77-1.60 (m, 7 H), 1.46-1.24 (m, 3 H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, d-DMSO-d6) δ 181.6, 175.1, 163.4, 149.7, 148.9, 140.7, 138.7, 131.7, 131.7, 131.1, 127.7, 125.8, 123.1, 121.3, 120.1, 45.3, 39.3, 34.0, 32.5, 25.1, 22.0, 21.9. HRMS, calc’d for C21H21N3O3Cl [M + H]+, 398.1271; found 398.1271.

N-(3-Chloro-4-(2,5-dioxo-3-phenylpyrrolidin-1-yl)phenyl)picolinamide (15k)

Following the general procedure, N-(3-chloro-4-(2,5-dioxo-3-phenylpyrrolidin-1-yl)phenyl)picolinamide was obtained as a mixture of diastereomers (dr 2:1). Major diastereomer: LCMS: RT = 1.370 min, >98% @ 254 nM, m/z = 406.2 [M + H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, d-DMSO-d6 ) δ 11.03 (br s, 1 H), 8.76 (d, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 8.28 (d, 1 H, J = 2.4 Hz), 8.17 (d, 1 H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.08 (ddd, 1 H, J = 7.6, 7.6, 1.6 Hz), 8.01 (dd, 1 H, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz), 7.72-7.68 (m, 1 H), 7.52-7.30 (m, 6 H), 4.36 (dd, 1 H, J = 9.6, 5.2 Hz), 3.42 (dd, 1 H, J = 18.4, 9.6 Hz), 2.97 (dd, 1 H, J = 18.4, 5.2 Hz). 13C NMR (125 MHz, d-DMSO-d6, mixture of diasteromers) δ 177.1, 175.4, 175.1, 163.3, 149.5, 148.7, 140.8, 140.7, 138.9, 138.5, 137.9, 131.8, 131.7, 131.2, 130.9, 129.3, 129.1, 128.7, 128.4, 127.9, 127.7, 126.0, 125.9, 123.2, 121.4, 121.3, 120.24, 120.15, 46.5, 46.2, 37.7, 37.5. HRMS, calc’d for C22H17N3O3Cl [M + H]+, 406.0958; found 406.0958.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors warmly acknowledge Emily L. Days, Tasha Nalywajko, Cheryl A. Austin and Michael Baxter Williams for their critical contributions to the HTS portion of the project and Matt Mulder, Chris Denicola, Nathan Kett and Sichen Chang for the purification of compounds utilizing the mass-directed HPLC system and Katrina Brewer for technical assistance with the PK assays. The dog cassette in vivo experiment was performed at Calvert Labs, and the rhesus in vivo experiment was performed at the Yerkes Primate Center at Emory University. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Vanderbilt Department of Pharmacology and the Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology. In addition, the authors would like to thank the NIH/MLPCN (5U54MH084659-02) for support of this research. Vanderbilt is a member of the MLPCN and houses the Vanderbilt Specialized Chemistry Center for Accelerated Probe Development. VU0400195, 20f, has been declared an MLPCN mGlu4 probe (ML 182, CID 46869947, MLS#003171619) and is available from BioFocus, South San Francisco, CA.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: SAR: structure-activity relationship; mGluR: metabotropic glutamate receptor; PAM: positive allosteric modulator; HTS: high-throughput screening; Clint: intrinsic clearance; PPB: plasma protein binding; AUC: area under the curve; GPCR: G-protein coupled receptor; 1: N-phenyl-7-(hydroxyimino)cyclopropa[b]chromen-1a-carboxamide; CNS: central nervous system; PD: Parkinson’s disease; GIRK: G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channel; CYP: cytochrome P450; TPSA: topological polar surface area; CLHEP: predicted hepatic clearance; B/P: brain:plasma ratio; CRC: concentration-response curve; %fu: percent free, unbound; DA: dopamine; PK: pharmacokinetics; BBB: blood-brain barrier; MW: molecular weight; FS: fold shift; RLM: rat liver microsomes.

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures, spectroscopic data, and NMR data for selected compounds and biological procedures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schapira AHV. Neurobiology and treatment of Parkinson's disease. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2009;30:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hefti FF. Parkinson's Disease. Drug Discovery for Nervous System Diseases. 2005:183–204. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fahn S. Description of Parkinson's disease as a clinical syndrome. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;991:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warner TT, Schapira AHV. Genetic and environmental factors in the cause of Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 2003;53:S16–S25. doi: 10.1002/ana.10487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jellinger KA. Recent developments in the pathology of Parkinson's disease. J. Neural Trans. 2002;62:347–376. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6139-5_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkinson J. An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. London, Sherwood, Neely and Jones. 1817 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fahn S. The history of dopamine and levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2008;23:S497–S508. doi: 10.1002/mds.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baas H, Beiske AG, Ghika J, Jackson M, Oertel WH, Poewe W, Ransmayr G. Catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition with tolcapone reduces the "wearing off" phenomenom and levodopa requirements in fluctuating Parkinsonian patients. Neurology. 1998;50:S46–S53. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5_suppl_5.s46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stocchi F. The levodopa wearing-off phenomenon in Parkinson's disease: pharmacokinetic considerations. Exp. Opin. Pharmacother. 2006;7:1399–1407. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.10.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marek K, Jennings D, Seibyl J. Do dopamine agonists or levodopa modify Parkinson's disease progression? Eur. J. Neurol. 2002;9:15–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.9.s3.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conn PJ, Battaglia G, Marino MJ, Nicoletti F. Metabotropic glutamate receptors in the basal ganglia motor circuit. Nature Rev. Neuroscience. 2005;6:787–798. doi: 10.1038/nrn1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conn PJ, Pin J-P. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conn PJ, Christopoulos A, Lindsley CW. Allosteric modulators of GPCRs: a novel approach for the treatment of CNS disorders. Nature Rev. Drug. Dis. 2009;8:41–54. doi: 10.1038/nrd2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuomo D, Martella G, Barabino E, Platania P, Vita D, Madeo G, Selvam C, Goudet C, Oueslati N, Pin J-P, Acher F, Pisani A, Beurrier C, Melon C, Kerkerian-LeGoff L, Gubellini P. Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 4 selectively modulates both glutamate and GABA transmission in the striatum: implications for Parkinson's disease treatment. J. Neurochem. 2009;109:1096–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindsley CW, Niswender CM, Engers DW, Hopkins CR. Recent Progress in the Development of mGluR4 Positive Allosteric Modulators for the Treatment of Parkinson's Disease. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009;9:949–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopkins CR, Lindsley CW, Niswender CM. mGluR4 Positive Allosteric Modulation as Potential Treatment of Parkinson's Disease. Future Med. Chem. 2009;1:501–513. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engers DW, Niswender CM, Weaver CD, Jadhav S, Menon UN, Zamorano R, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Hopkins CR. Synthesis and evaluation of a series of heterobiarylamides that are centrally penetrant metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGluR4) positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:4115–4118. doi: 10.1021/jm9005065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engers DW, Field JR, Le U, Zhou Y, Bolinger JD, Zamorano R, Blobaum AL, Jones CK, Jadhav S, Weaver CD, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Niswender CM, Hopkins CR. Discovery, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship development of a series of N-(4-acetamido)phenylpicolinamides as positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGlu4) with CNS exposure in rats. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:1106–1110. doi: 10.1021/jm101271s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.East SP, Bamford S, Dietz MGA, Eickmeier C, Flegg A, Ferger B, Gemkow MJ, Heilker R, Hengerer B, Kotey A, Loke P, Schänzle G, Schubert H-D, Scott J, Whittaker M, Williams M, Zawadzki P, Gerlach K. An orally bioavailable positive allosteric modulator of the mGlu4 receptor with efficacy in an animal model of motor dysfunction. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:4901–4905. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Compounds 1 (PHCCC), 2 (VU0155041), and 3 (VU0361737) are now available from TOCRIS bioscience (Cat. Nos. 1027, 3248, and 3707, respectively).

- 22.Niswender CM, Lebois EP, Luo Q, Kim K, Muchalski H, Yin H, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Positive allosteric modulators of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 4 (mGluR4): Part I. Discovery of pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidines as novel mGluR4 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:5626–5630. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams R, Niswender CM, Luo Q, Le U, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Positive allosteric modulators of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 4 (mGluR4). Part II: Challenges in hit-to-lead. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:962–966. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engers DW, Gentry PR, Williams R, Bolinger JD, Weaver CD, Menon UN, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Niswender CM, Hopkins CR. Synthesis and SAR of novel, 4-(phenylsulfamoyl)phenylacetamide mGlu4 positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) identified by functional high-throughput screening (HTS) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:5175–5178. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niswender CM, Johnson KA, Luo Q, Ayala JE, Kim C, Conn PJ, Weaver CD. A novel assay of Gi/o-linked G protein-coupled receptor coupling to potassium channels provides new insights into the pharmacology of the group III metabotropic glutamate receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;73:1213–1224. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds IJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors as therapeutic targets in Parkinson's disease. 6th International Meeting on Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors; 14 September – 19 September 2008; Taormina, Sicily, Italy. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slee DH, Zhang X, Moorjani M, Lin E, Lanier MC, Chen Y, Rueter JK, Lechner SM, Markison S, Malany S, Joswig T, Santos M, Gross RS, Williams JP, Castro-Palomino JC, Cresp MI, Prat M, Gual S, Díaz J-L, Wen J, O'Brien Z, Saunders J. Identification of novel, water-soluble, 2-amino-N-pyrimidin-4-yl acetamides as A2A receptor antagonists with in vivo efficacy. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:400–406. doi: 10.1021/jm070623o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.VU0400195 (ML182) has been declared a probe via the Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network (MLPCN) and is available through the network, see: http://mli.nih.gov/mli/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.