Abstract

Background and purpose

Sildenafil provides restorative therapeutic benefits in the treatment of experimental stroke. The majority of experimental studies on treatment of stroke have been performed in young animals; however, stroke is primarily a disease of the aged. Thus, using MRI, we evaluated the effects of sildenafil treatment of embolic stroke in aged animals.

Methods

Aged male Wistar rats (18 months) were subjected to embolic stroke and treated daily with saline (n=10) or with sildenafil (n=10) initiated at 24h and subsequently for 7 days after onset of ischemia. MRI measurements were performed at 24h and weekly to 6 weeks after embolization.

Results

MRI and histological measurements demonstrated that sildenafil treatment of aged rats significantly enhanced angiogenesis and axonal remodeling after stroke compared to saline treated aged rats. Local CBF in the angiogenic area was elevated and expansion of the ipsilateral ventricle and consequently brain atrophy was significantly reduced in the sildenafil treated rats.

Conclusions

Treatment of embolic stroke in aged rats with sildenafil significantly augments angiogenesis and axonal remodeling, which increased local blood flow and reduced expansion of the ipsilateral ventricle 6 weeks after stroke, compared to control aged rats. MRI can be employed to investigate brain repair after stroke in aged rats.

Keywords: aged rat, embolic stroke, magnetic resonance imaging, neurorestorative treatment, sildenafil

Introduction

Advanced age is an important risk factor for stroke and a predictor of poorer outcome after stroke in elderly patients compared with younger patients1. During aging, many physiological and pathophysiological functions are altered. Aged rats exhibit marked decreases in brain proteasomal activity compared with young rats after induction of intermittent hypoxia, which is associated with greater impairment of spatial learning2. Aged rats subjected to stroke have a higher mortality rate and worse neurological deficits than young rats, and pharmacological effects after treatment of stroke in young rats may not necessarily translate to older rats3-5. The vast majority of experimental studies of stroke have been performed in young animals, and the failure to translate laboratory data showing therapeutic benefit of treatment to the stroke patient may in part be attributed to the failure to perform preclinical studies in aged animals.

By inhibiting cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) breakdown6, sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor, causes intracellular accumulation and increased brain levels of cGMP7. Administration of sildenafil significantly increases the cortical levels of cGMP in both hemispheres for non-ischemic young rats7, and in the ipsilateral hemisphere at 7 days after stroke for both ischemia insulted young and aged rats compared with levels in non-treated stroke animals3. Elevated cGMP levels in cerebral tissues may promote angiogenesis during recovery up to 4 weeks after embolic stroke in both young and aged rats3. However, aged rats exhibit a significant reduction of vascular density and impairment of functional recovery after stroke compared with young rats, and age was also associated with a reduction of elevated cGMP levels after treatment of stroke with sildenafil in rats3. The primary effect of sildenafil is vasorelaxing, which may cause a decrease of blood pressure. However, the dose of sildenafil administered in current study did not cause the blood pressure outside the normal biophysical ranges.

Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), angiogenic cerebral tissue after ischemic stroke in young rats can be identified by T2*-weighted imaging (T2*WI) with or without sildenafil treatment8. Accordingly, elevated regional cerebral blood flow (CBF) has been measured in the ischemic boundary zone (IBZ) using perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI) with continuous arterial spin labeling9. Diffusion anisotropy (DA) derived from diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) in three mutual perpendicular directions10, provides a means for delineating the anatomic connectivity of white matter11, and was used to detect pathologic tract disruption and remodeling after stroke in adult rats9. A recent MRI study demonstrated that after stroke, the volume of the ipsilateral ventricle measured by T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) is a sensitive index of cerebral tissue loss (brain atrophy) and repair in young rats with or without erythropoietin treatment12. However, whether MRI can identify brain remodeling after stroke in aged rats with or without a restorative treatment, remains unknown, because of the decreased recovery ability, worse stroke deficits and significant reduction of therapeutic response to treatment after stroke in aged rats.

We, therefore, tested the hypothesis that MRI can also detect enhanced neurorestorative processes after stroke in aged rats treated with sildenafil compared with saline treatment.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model and Experimental Protocol

All studies were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal research under a protocol approved by the IACUC of Henry Ford Hospital.

Male Wistar rats (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) 18 months of age and weighing approximate 560g were subjected to embolic stroke and randomly assigned to either the treatment (n=10) or control groups (n=10). The model of embolic stroke9, briefly, employs a 4cm long aged clot, and slowly injected into the internal carotid artery to the origin of the middle cerebral artery (MCA).

In the treatment group, sildenafil (Viagra®, Pfizer Inc) was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 10mg/kg daily for 7 days starting 24 hours after MCA occlusion. The selected dose has been previously shown to be effective for this model3. The control group received an equal volume of saline.

MRI and functional tests (including adhesive-removal test, foot-fault test and a modified neurological severity score, mNSS) were performed 24h and weekly to 6 weeks after stroke for all rats in a double-blind fashion. All animals were euthanized 6 weeks after stroke.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measurements

MRI measurements were performed using a 7T Bruker system (Bruker-Biospin Inc, Billerica, MA, USA). During MRI measurements, anesthesia was maintained using a gas mixture of N2O (70%), O2 (30%), and isoflurane (1.00-1.50%). Rectal temperature was kept at 37°C±1.0°C using a controlled water bath.

A tri-pilot sequence was used for reproducible positioning of the animal in the magnet at each MRI session. MRI measurements (including T2WI for ischemic lesion and ventricular volumes, T2*WI for angiogenesis, DWI for axonal remodeling and PWI for CBF) were performed, as previously described9.

Histology

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (44mg/kg i.p.) and xylazine (13mg/kg i.p.), and transcardially perfused with heparinized saline followed by 10% neutral buffered formalin. The brain was immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline at 4°C overnight, and seven 2mm-thick blocks of brain tissue were cut, processed and embedded in paraffin.

The MicroComputer Imaging Device (MCID) system (Imaging Research, Ontario, Canada) was used with a 40x objective (Olympus BX40) and a 3-CCD color video camera (Sony DXC-970MD) for histological measurements. Coronal 6μm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to evaluate cerebral infarction; with endothelial barrier antigen (EBA) to quantify cerebral vessels; with Bielschowsky’s silver and Luxol fast blue (B&LFB) to assess myelinated axons. Four field-of-views (FOVs) in each coronal section were used for quantification.

Data and Statistical Analysis

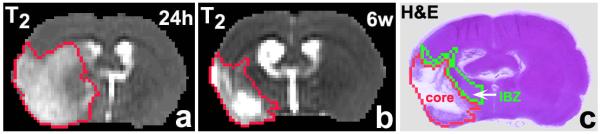

MRI images acquired at various times and histological section images were reconstructed, coregistered and analyzed using a homemade software package, “Eigentool”9. The difference of the ischemic lesion sizes in T2 maps acquired at 24 hours (Fig.1a) and 6 weeks (Fig.1b) after stroke are referred to as the recovery area (Fig.1c)9. T2*, CBF and DA values of recovery ischemic tissue and homologous tissue mirrored in contralateral hemisphere were also measured and were used to obtain ratios.

Figure 1.

T2 map acquired 24h after stroke (a) shows lesion volume. T2 map acquired 6w after MCAo (b) identifies the final infarction and expansion of the ipsilateral ventricle. The ischemic boundary zone (green) and core (red) are shown on the H&E slice (c) warped to the 6w T2 map.

Ventricular or ischemic lesion volumes were determined by T2 maps were acquired after stroke, using values above the mean plus two standard deviations (SD) of the contralateral measurements. The total volumes were the sum of the volumes in the five central slices12.

MRI measurements are summarized as mean value with SD. Differences in the MRI data between groups were analyzed by a mixed model of analysis of variance (ANOVA) and covariance (ANCOVA). For the longitudinal MRI measurements, the analysis started testing the group and time (without baseline time point) interaction, followed by testing the group difference at each time point if the interaction or overall group effect was detected at the 0.05 level.

Results

Stroke was induced in 48 aged rats, 26 of whom died (19 within 24h, 6 between 24h and 48h, and 1 at 1w), yielding a mortality rate of 54%. The primary reason of mortality is due to stroke complication. Two rats were excluded from the study because the T2 maps acquired at 24h after stroke showed no ischemic lesion. Ischemic lesion volumes using H&E sections were measured as 26.6±9.4% of ipsilateral hemisphere for the sildenafil treated rats and 26.7±7.3% for the control rats 6w after stroke. No differences were found for the lesion volumes between the treated and control groups of the aged rats (p>0.9).

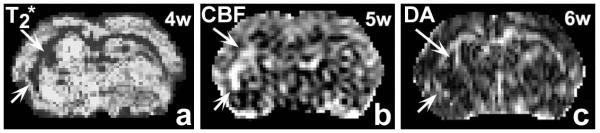

T2* maps detected low intensity regions after stroke along the ischemic boundary in both control (treated with saline) and sildenafil treated aged rats. On a typical T2* map obtained 4w after stroke from a representative aged rat treated with sildenafil whose ischemic lesion area was demarcated by hyperintensity on a T2 map acquired 24h after stroke (Fig.1a), hypointensity regions were apparent (two white arrows in Fig.2a). One week later, the CBF map obtained from the same rat revealed elevation of CBF values (indicated by arrows in Fig.2b) in the areas of hypointensity measured on the T2* map. Six weeks after stroke (two weeks after the identification of hypointensity region on the T2* map), the area with elevated CBF exhibited increases of DA values analyzed by diffusion measurements (identified by arrows in Fig.2c). The ischemic lesion size and expansion of the ipsilateral ventricle after stroke in this treated rat were demonstrated on the T2 maps acquired 6 weeks after MCA occlusion (Fig.1b). In contrast, for the control aged rats, the hypointensity region on T2* map and hyperintensity areas on CBF and DA maps, respectively, were much less obvious. Quantitative MRI measurements were then employed to analyze temporal changes in aged rats after stroke.

Figure 2.

For a representative aged rat with sildenafil treatment after ischemia, the hypointensity regions in T2* map (a) were obtained 4w after stroke. The elevated CBF was observed 1 week later (b). Six weeks after stroke, an increase of DA values was apparent (c).

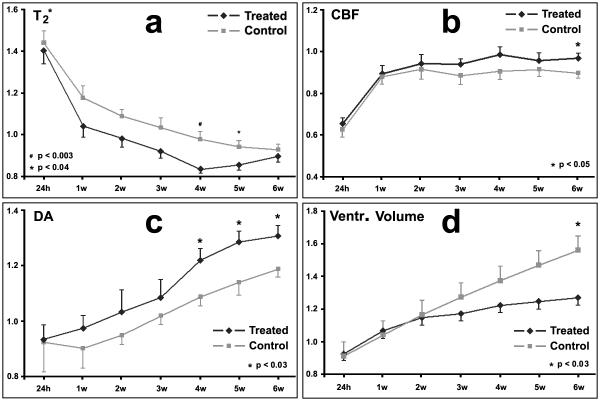

Quantitative longitudinal MRI measurements demonstrated temporal features of T *2, CBF and DA for restorative cerebral tissue after stroke with or without sildenafil treatment in the aged rats. Compared to the control aged rats, T *2 ratios (Fig.3a) of cerebral tissue along the IBZ in the sildenafil treated group had consistently lower values during the 6 weeks after stroke. After the initial decrease, however, T2* ratios increased starting from 5w in the treated group. T *2 ratios monotonically decreased in the control group to 6w after stroke.

Figure 3.

T2* ratios (a) of cerebral tissue in the sildenafil treated group had lower values during 6 weeks after stroke than in the control group; the differences were significant at 4w and 5w after stroke (p<0.04). Higher CBF ratios were observed in sildenafil treated aged animals compared to control rats (b). At 6w after stroke, CBF was significantly higher in treated group than in the control group (p<0.05). DA values monotonically increased after stroke in aged rats (c). Starting from 4w after stroke, the DA ratios were significantly different between the two groups (p<0.03). Ventricular volume ratios monotonically increased after stroke for all aged rats (d). However, the increasing rate was slower in the treated group, and was significant at 6 weeks after stroke.

Higher CBF ratios were observed in sildenafil treated aged animals during the experiments (24h to 6w after stroke), in contrast to control aged rats (Fig.3b).

DA values monotonically increased after stroke in the sildenafil treated group, but, were delayed by 1 week in controls (Fig.3c). Higher DA ratios were measured in treated rats than in control rats during the experiments.

Temporal changes of ventricular volume ratios (ipsilateral vs contralateral) for both treated and control groups of aged rats are shown in Fig.3d. Ventricular volume ratios monotonically increased during 6 weeks after stroke for both treated and control groups. However, the rate of increase was slower in the treated group from 1 week after stroke.

ANCOVA demonstrated that the stroke severity was balanced between the groups at the baseline (at day 1 with p>0.33). For T2* measurements, no group-by-time interaction was observed (p=0.63), however, there was a significant group effect and time effect with p<0.01, respectively. Subgroup analysis showed treatment effect on T2* at weeks 4 and 5. The overall treatment effect was observed on CBF at 6w (p<0.05), and no treatment-by-time interaction was observed for CBF. As for DA, there was no group-by-time interaction (p=0.94), however, overall group effect and time effect was observed, respectively. Subgroup analysis showed a significant treatment effect at weeks 4, 5 and 6, respectively. DA increased as time increased in both groups. The significant difference of group-by-time interaction was detected (p<0.01) in volume expansion of ventricle. The sildenafil treatment reduced expansion of the ipsilateral ventricular volume at 6 weeks after stroke, compared to controls (p<0.03). As a baseline, we measured the volumes of the contralateral ventricle for all animals with T2 maps, and no significant differences were observed at 6 weeks after stroke between the two groups (p>0.4).

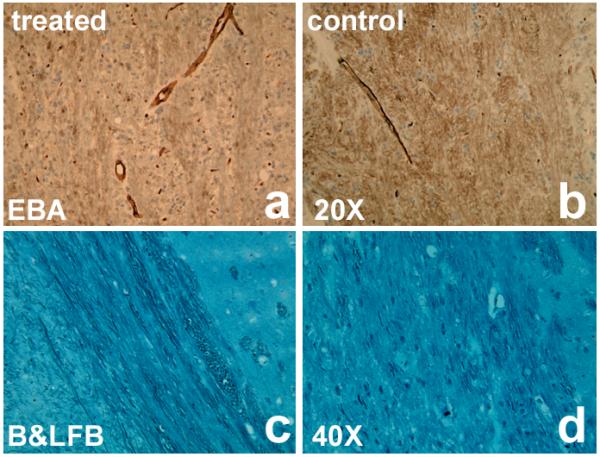

Histological measurements along the IBZ were consistent with MRI results. Using the EBA-stained sections, the microvascular density of the representative treated aged rat (Fig.4a) was increased compared with a control aged rat (Fig.4b), with the measurements of 462.5±86.9mm−2 and 315.3±45.4mm−2 for the sildenafil treated and control groups (p<0.05), respectively. And using the sections with B&LFB staining, the axonal length and density at the same location were longer and higher in the treated aged rat (Fig.4c) than in the control aged rat (Fig.4d), with the measurements of 28.9±3.0% vs 20.6±4.3% of FOV for the sildenafil treated and control groups (p<0.05).

Figure 4.

the EBA-stained section of the microvascular density from a representative treated aged rat (a) was increased compared with a control aged rat (b). And the axonal length and density at the same location were longer and higher in the treated aged rat (c) than in the control aged one (d) on B&LFB-stained sections. Bars in b & d are 50μm.

Neurological tests demonstrated that the mNSS was improved at week 6 in the sildenafil treated group (Table 1), compared to controls (p<0.04). The mNSS decreased as time increased (p<0.01) in both groups. No significant differences were found for adhesive-removal and foot-fault tests between the two groups to 6w after stroke (data are not shown).

Table 1.

mNSS of the aged rats after stroke with and without sildenafil treatments

| 24h | 1w | 2w | 3w | 4w | 5w | 6w | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated group | 11.5±0.5 | 9.9±0.6 | 8.6±0.8 | 7.4±1.0 | 6.3±1.1 | 5.4±1.0 | 4.7±0.7* |

| Control group | 11.2±0.8 | 9.4±0.5 | 8.0±0.5 | 7.2±0.6 | 6.5±0.7 | 6.0±0.9 | 5.4±0.7 |

p<0.04 between the treated (n=10) and control (n=10) groups of the aged rats.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that treatment of embolic stroke with sildenafil in aged rats starting at 24 hours and continuing daily for 7 days significantly promoted angiogenesis, detected by hypointensity region on T2* map and axonal remodeling, detected by hyperintensity area on DA map, increased local cerebral blood flow and reduced expansion of the ipsilateral ventricle in the ischemic recovery area at 6 weeks after stroke, compared to control aged rats treated with saline. Concomitantly, neurological outcome by mNSS evaluation was significantly improved after sildenafil treatment of stroke in aged rats.

In a previous study with young adult rats, T2* map provided evidence of ongoing angiogenic cerebral tissue after stroke with hypointensity regions on T2* maps along the ischemic boundary8. Low value areas on the T2* map may result from the increase of microvascular density due to angiogenesis and leakage of the newly-formed blood vessels due to the incomplete blood-brain barrier. Due to the coupling of angiogenesis with neurogenesis by vascular endothelial growth factor and improvement of the microenvironment after angiogenesis, axonal remodeling can be detected using DA map9. Hyperintensity areas in the DA map along the ischemic boundary after stroke primarily result from increases of axonal density and directionality. The increase of axonal density in rat brain after stroke could be caused by axonal outgrowth and remyelination. Volume expansion of the ipsilateral ventricle after stroke is a sensitive index for assessing the cerebral tissue restoration from stroke damage12. Damage and loss of brain tissue after stroke may result in the expansion of ventricle. Treatment of stroke which enhances brain remodeling, may consolidate the cerebral tissue due to angiogenesis and axonal remodeling, and thereby reduce the ventricular expansion and concomitant brain atrophy.

In the current study with aged rats, a low intensity region on the T2* map in the sildenafil treated rat was detected at 4w after stroke (Fig.2a) and the increased CBF was present in the same location 1 week later (Fig.2b). The spatial and temporal consistencies of the T2* and CBF maps support the hypothesis, that the T2* map can detect ongoing angiogenesis in cerebral tissue and the angiogenesis results in an increase of local CBF within the angiogenic region. With the T2* measurements, the differences of angiogenesis in aged rats between the control and treated groups were significant at 4-5 weeks after stroke (Fig.3a). Angiogenesis in sildenafil treated aged rats appear to approach completion at 4 weeks after stroke, since the T2* value was minimum at 4 weeks and the regional CBF exhibited a significant difference between the groups 2 weeks later (Fig.3b). Furthermore, a hyperintensity area in the DA map was identified after detection of angiogenesis in the same location (Fig.2c). This suggests a coupling between angiogenesis and axonal remodeling. DA values monotonically increased starting from 1 week after stroke in the aged rats (Fig.3c), which suggests that axonal remodeling starts from 1 week after stroke. The sildenafil treatment significantly enhanced the axonal remodeling in aged rats at 4 weeks post stroke, compared to control aged rats.

These brain remodeling events suggest that the functional microvessels after angiogenesis increase local CBF and support the remodeling of neuronal fibers, which may rebuild the microstructure and increase the cerebral tissue density along the ischemic boundary. Thus, the reparative cerebral tissue may resist the ventricular expansion after stroke. In the control aged animals, MRI images did not exhibit apparent angiogenesis, elevation of CBF and reorganization of neuronal fibers up to 6 weeks after stroke, in contrast to sildenafil treated aged animals. Therefore, the ischemic cerebral tissue in the control rats may be unable to resist the ipsilateral ventricular expansion. Consequently, the reparative cerebral tissue in sildenafil treated aged rats significantly reduced the expansion rate of the ipsilateral ventricle at 6 weeks after stroke compared with control aged rats (Fig.3d).

Brain remodeling after ischemia may be age dependent. Compared with young adult rats, neurorestorative processes after stroke may be slower and weaker in aged rats3. We have previously demonstrated8, 9, that hypointensity regions on T2* maps, which characterizes cerebral tissue with ongoing angiogenesis, were present 2w~3w after stroke in young rats with or without sildenafil treatment, respectively. In the current study of aged rats, the angiogenic tissue was first detected on T2* maps at 4w after stroke in the sildenafil treated group, delayed compared to young animals9. The elevation of regional CBF and MRI features of axonal remodeling in sildenafil treated rats were identified on CBF and DA maps, correspondingly, later in the aged rats than in young rats. For most control aged animals, T2* and DA features of angiogenesis and axonal remodeling, however, were not apparent on the T2* and DA maps with the naked-eye at least to six weeks after stroke.

In our experimental studies, aged rats (18 months) were bigger than young rats (2~3 months). The increased weight of rats may cause smaller ischemic lesion volumes after stroke in aged rats, with 27±8% of the ipsilateral hemisphere, than in young rats, with 65±18% infarction, since the same lengths of the embolic clot (4cm) were used in the MCA occlusion stroke model for all young and aged rats. The smaller ischemic lesion volumes in aged rats may in part affect the temporal profile of brain remodeling, causing a weaker restorative response after stroke as compared with young rats. A longer embolic clot in the stroke model in the aged animals, which would produce a larger infarction to be comparable with young rats, would increase the mortality rate (data not shown) to untenable levels.

In summary, the present study demonstrated that sildenafil provides an effective therapy for stroke in the aged rats, although the therapeutic response to the sildenafil treatment was weaker and delayed in the aged rats compared to the young adults. Treatment of embolic stroke in aged rats with sildenafil administered 24h and subsequently daily for 7 days after stroke significantly augmented angiogenesis and axonal remodeling, which increased local blood flow and reduced expansion of the ipsilateral ventricle 6 weeks after stroke, compared to control aged rats. MRI can be employed to investigate and monitor cerebral tissue undergoing angiogenesis and axonal remodeling after stroke in aged rats with or without the sildenafil treatments.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by NINDS grants PO1 NS23393 (M.C.), RO1 NS48349 (Q.J.), RO1 HL64766 (Z.Z.) and the Mort and Brigitte Harris Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures

None.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chen RL, Balami JS, Esiri MM, Chen LK, Buchan AM. Ischemic stroke in the elderly: An overview of evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:256–265. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller JN, Gee J, Ding Q. The proteasome in brain aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2002;1:279–293. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(01)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L, Zhang RL, Wang Y, Zhang CL, Zhang ZG, Meng H, Chopp M. Functional recovery in aged and young rats after embolic stroke-treatment with a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor. Stroke. 2005;36:847–852. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158923.19956.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Futrell N, Garcia JH, Peterson E, Millikan C. Embolic stroke in aged rats. Stroke. 1991;22:1582–1591. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.12.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badan I, Buchhold B, Hamm A, Gratz M, Walker LC, Platt D, Kessler C, Popa-Wagner A. Accelerated glial reactivity to stroke in aged rats correlates with reduced functional recovery. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:845–854. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000071883.63724.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corbin JD, Francis SH. Cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase-5: Target of sildenafil. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13729–13732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang RL, Wang Y, Zhang L, Zhang ZG, Tsang W, Lu M, Zhang LJ, Chopp M. Sildenafil (viagra) induces neurogenesis and promotes functional recovery after stroke in rats. Stroke. 2002;33:2675–2680. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000034399.95249.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding G, Jiang Q, Li L, Zhang L, Zhang ZG, Ledbetter KA, Gollapalli L, Panda S, Li Q, Ewing JR, Chopp M. Angiogenesis detected after embolic stroke in rat brain using magnetic resonance T2*WI. Stroke. 2008;39:1563–1568. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.502146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding G, Jiang Q, Li L, Zhang L, Zhang ZG, Ledbetter KA, Panda S, Davarani SP, Athiraman H, Li Q, Ewing JR, M C. Magnetic resonance imaging investigation of axonal remodeling and angiogenesis after embolic stroke in sildenafil-treated rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1440–1448. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Gelderen P, de Vleeschouwer MHM, DesPres D, Pekar J, van Zijl PCM, Moonen CTW. Water diffusion and acute stroke. Magn Reson Med. 1994;31:154–163. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910310209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaulieu C. The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nerve system - a technical review. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:435–455. doi: 10.1002/nbm.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding G, Jiang Q, Li L, Zhang L, Wang Y, Zhang ZG, Lu M, Panda S, Li QJ, Ewing JR, Chopp M. Cerebral tissue repair and atrophy after embolic stroke in rat: A magnetic resonance imaging study of erythropoietin therapy. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:3206–3214. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]