Type 2 diabetes is a well-recognized risk factor for cerebrovascular disease. In this issue of Stroke, Thacker and colleagues demonstrate that earlier abnormalities in carbohydrate metabolism, insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance, are also associated with increased risk for cerebral ischemic events1. These findings are reliable and timely, and they have immediate implications for the design of the next generation of stroke prevention trials.

Abnormal carbohydrate metabolism comprises a spectrum of disorders characterized by impaired energy utilization. Early manifestations include obesity, decreased insulin sensitivity, impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). The latter two conditions are often referred to as ‘pre-diabetes’ – a stark description of their typically progressive nature. Its most advanced manifestation, type 2 diabetes, results from the inexorable loss of insulin secretory capacity in the face of well-established insulin resistance. These metabolic states have become endemic in most countries as westernized lifestyles are adopted. In the US alone, there are now 26 million individuals with diabetes and 79 million with pre-diabetes. It is estimated that by 2030, there will be 366 million people with diabetes throughout the world.

Clinicians who care for stroke patients know that metabolic disease is also prevalent in this population. Among patients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease 18%-30% are obese, 25%-30% are insulin resistant, 23%-28% have impaired glucose tolerance, and 13%-36% have diabetes2-5.

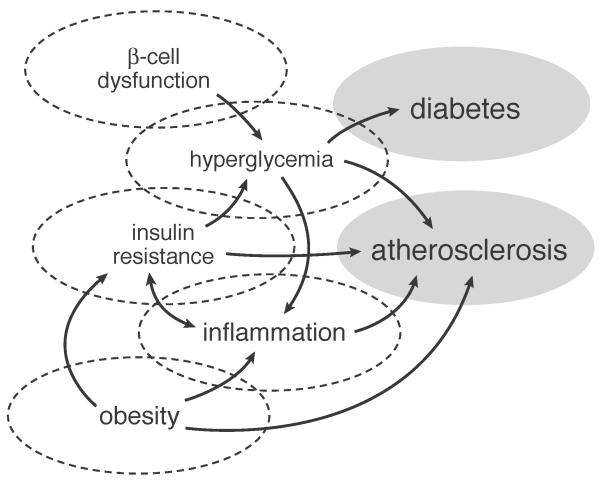

Figure 1 illustrates a model of impaired glucose regulation and its potential causal relatinship to stroke. Each of its cardinal manifestations (i.e., obesity, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, diabetes) have been associated with increased risk for stroke6. However, the evidence is strongest for obesity and diabetes, possibly because these are easiest to measure and classify. Obesity (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2) doubles the risk for ischemic stroke, although the effect appears to be substantially mediated by coexistant cardiovascular risk factors7, 8. Importantly, not all obese patients exhibit these complications; indeed about 25% of those with obesity lack additional evidence for the metabolic syndrome; that is, they do not have hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, or evidence of vascular inflammation, insulin resistance, or endothelial dysfunction that typically characterizes this condition9. Adipose tissue topography may explain some of these differences, since patients with so-called “uncomplicated obesity” may have fat distributed preferentially to more metabolically quiescent sites such as arms, legs, and buttocks9, as opposed to the more metabolically active centripetal sites, including liver and omentum. It is not surprising, therefore, that waist-hip-ratio (a reflection of central obesity) has a closer association with stroke risk than BMI (odd ratio adjusted for risk factors including diabetes and BMI=3.0, 95% CI 2.1-4.2)10.

figure 1.

A model of impaired carbohydrate regulation and its potential causal relation to ischemic stroke

Obesity is a major contributing risk factor to the development of insulin resistance leading to type 2 diabetes. Patients with diabetes have 2-3 times the risk of ischemic stroke compared with non-diabetic patients after adjusting for blood pressure and other risk factors6, 11. In addition, on average patients with diabetes tend to have strokes about two years earlier than non-diabetic patients12.

The distinct importance of the study by Thacker and colleagues is in confirming that pre-diabetic conditions, including insulin resistance and post-load hyperglycemia, are associated with increased risk for stroke. The investigators conducted an observational cohort study of 3442 community-based participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study who were free of stroke and diabetes at baseline. To classify glucose and insulin resistance status, participants underwent an oral glucose tolerance test. Insulin and glucose measures at baseline and 2 hours were used to calculate the Gutt insulin sensitivity index. This measure of insulin sensitivity is more accurate than the fasting insulin alone or the popular HOMA index, which is calculated from fasting insulin and glucose concentrations and reflects predominantly hepatic insulin resistance. The Gutt index factors in post-load glucose and insulin levels which reflect, to a large degree, peripheral (i.e., skeletal muscle) insulin resistance. This is important because peripheral insulin resistance is more closely aligned with vascular risk. The main outcome, ischemic stroke, was confirmed by medical record review. Participants were followed from enrollment in 1989/90 to 2007 (17 years).

Risk for ischemic stroke (adjusted for age, sex, race, renal function, coronary disease, atrial fibrillation and peripheral arterial disease) was significantly increased for persons in the fourth quartile of insulin sensitivity (i.e., more insulin resistant) compared with the first (RR= 1.64, 95% CI 1.24-2.16). Further adjustment for blood pressure and cholesterol attenuated the risk but it remained significant (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.05-1.86). Two-hour serum glucose was also associated with increased risk for ischemic stroke in the fully adjusted model (RR = 1.57, 95% CI 1.18-2.09).

The findings by Thatcher et al are driven by the two-hour glucose and insulin values. Fasting glucose and fasting insulin concentrations were not associated with increased risk for ischemic stroke. The greater relative importance of IGT is expected6, 13, 14, but the absence of any observed effect of IFG on risk for ischemic stroke is surprising. An important body of research suggests that fasting glucose in the non-diabetic range remains positively associated with vascular disease risk15 , including ischemic stroke specifically6. The same is true for fasting insulin16. Indeed fasting and post-prandial glucose and insulin levels are linked, and the variable findings from studies exploring this question may be the result of methodology rather than true biological differences. Hemoglobin A1c, which incorporates fasting and post-prandial hyperglycemia, also appears to be a more robust marker of vascular risk than fasting glucose15.

While the research methods used by Thatcher and colleagues are generally sound, their results may have actually underestimated the association between insulin resistance and risk for stroke due to over-adjustment in their second multivariable model. Insulin resistance can increase blood pressure through mechanisms that include up-regulation of endothelin 1, microvascular dysfunction, and two properties of insulin which appear to be unimpaired in insulin resistant states, namely renal sodium retention and activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Hyperinsulinemia, especially in a hyperglycemic milieu, also increases liver triglyceride synthesis and thereby indirectly lowers HDL-cholesterol concentrations. Hypertension and dyslipidemia, therefore, may represent intermediate mechanisms by which insulin resistance increases stroke risk; adjustment for them may, therefore, attenuate the association statistically.

The paper by Thatcher and colleagues is one of several studies16-18 to examine the link between insulin resistance and risk for ischemic stroke, but only the second18 to measure peripheral insulin resistance using more robust techniques based on glucose challenge, either with oral loading or glucose infusion. All studies have suggested an association and most report relative risks or hazard ratios at about 2.0 or higher. In the context of these other studies, Thatcher and colleagues report a weaker association (RR=1.64, 95% CI 1.24-2.16 in the first adjusted model), although it still reaches clinical significance. IGT has also been associated with increased risk for stroke, although the data are more scarce6, 19.

This confirmatory paper by Thacker and colleagues should lay to rest any doubt that insulin resistance and IGT are important risk factors for ischemic stroke. More importantly, this work should provide new impetus to developing effective approaches to ‘metabolic rehabilitation’ both for prevention of first stroke and secondary prevention of vascular disease of all types in patients with a recent ischemic stroke or TIA. Abnormal carbohydrate metabolism harms blood vessels over many years. To have the greatest impact in preventing macrovascular events, therefore, metabolic rehabilitation may need to target those with the earliest manifestations (e.g. obesity, insulin resistance, pre-diabetes).

Models for effective metabolic rehabilitation have been developed, but none are adequate for prevention of first or recurrent stroke. Cardiac rehabilitation programs typically last 12 weeks and emphasis physical activity. They have been associated with reduced all-cause mortality, but sustained effects on weight, long-term vascular outcomes, and diabetes prevention have not been demonstrated20. Similarly, diet programs directed at weight loss generally produce results in the short term, but weight is typically regained within a few years and the clinical significance of the loss has not been determined21. Unsupported office-based advice to increase physical activity or lose weight is generally ineffective22. For sustained weight loss, intensive programs involving personalized coaching for both fitness and nutrition, meal provision (at least initially), and continuous participation over years seem to be required23, 24. Such intensive efforts, as exemplified by the Diabetes Prevention Program23, are expensive and require a high level of commitment from participants. Even these intensive programs produce only modest weight loss over the long term. Nevertheless, sustained multi-disciplinary program-based models may be the best we have to offer in the near term.

Because changing human behavior is difficult, pharmacotherapy and surgery are popular among patients, clinicians, and researchers. Pharmacotherapy has a second-tier role in diabetes prevention (next to lifestyle modification) and a marginal role as adjunctive therapy for weight loss. The NINDS is currently funding the Insulin Resistance Intervention after Stroke (IRIS) trial to determine the effectiveness of the insulin-sensitizer, pioglitazone, in prevention of recurrent stroke and myocardial infarction among non-diabetic patients with a recent ischemic stroke or TIA and insulin resistance (NCT 00091949). If this study proves positive, a new avenue of clinical investigation may open. Other pharmacological agents with insulin sensitizing effects include other thiazolidinediones, non-thiazolidinedione PPAR agonists, 11β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 inhibitors, protein tyrosine phosphatase-1b inhibitors, and acetyl-coA Carboxylase-1 and -2 inhibitors. For selected patients, bariatric surgery is successful in preventing progression to diabetes25, but effects on vascular events and mortality remain uncertain26.

Thacker and colleagues have added to the scientific basis for a new generation of research on metabolic disease and stroke. Until these investigations bear fruit, we recommend that patients with ischemic stroke be screened for diabetes and pre-diabetes and that those with abnormal findings are encouraged to enter and remain in structured programs for fitness and good nutrition.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. Kernan and Inzucchi are conducting a clinical trial that is funded by the US NIH (NCT 00091949). Placebo and active pioglitazone tablets are provided by Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America. Dr. Inzucchi receives less than $10,000 annually as a consultant to Takeda.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Thacker EL, Psaty BM, McKnight B, Heckbert SR, Longstreth WT, Mukamal KJ, Meigs JB, de Bor IH, et al. Fasting and post-load measures of insulin resistance and risk of ischemic stroke in older adults. Stroke. 2011 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.620773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matz K, Keresztes K, Tatschl C, Nowotny M, Dachenhausen A, Brainin M, et al. Disorders of glucose metabolism in acute stroke patients. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:792–797. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Inzucchi SE, Brass LM, Bravata DM, Shulman GI, et al. Prevalence of abnormal glucose tolerance following a transient ischemic attack or ischemic stroke. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:227–233. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furie K, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, Albers GW, Bush RL, Fagan SC, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42:227–276. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urabe T, Watada H, Okuma Y, Tanaka R, Ueno Y, Miyamoto N, et al. Prevalence of abnormal glucose metabolism and insulin resistance among subtypes of ischemic stroke in Japanese patients. Stroke. 2009;40:1289–1295. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.522557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyvarinen M, Tuomilehto J, Mahonen M, Stehouwer CDA, Pyorala K, Zethelius B, et al. Hyperglycemia and incidence of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke-comparison between fasting and 2-hour glucose criteria. Stroke. 2009;40:1633–1637. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.539650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Rexrode KM, Kase CS, Cook NR, Manson JE, et al. Prospective study of body mass index and risk of stroke in apparently healthy women. Circulation. 2005;111:1992–1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161822.83163.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Berger K, Kase CS, Rexrode KM, Cook NR, et al. Body mass index and the risk of stroke in men. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2557–2562. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.22.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefan N, Kantartzis K, Machann J, Schick F, Thamer C, Rittig K, et al. Identification and characterization of metabolically benign obesity in humans. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1609–1616. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suk S-H, Sacco RL, Boden-Albala B, Cheun JF, Pittman JG, Elkind MS, et al. Abdominal obesity and risk of ischemic stroke. The northern manhattan stroke study. Stroke. 2003;34:1586–1592. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000075294.98582.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folsom AR, Rasmussen ML, Chambless LE, Howard GE, Cooper LS, Schmidt MI, et al. Prospective associations of fasting insulin, body fat distribution, and diabetes with risk of ischemic stroke. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1077–1083. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kissela B, Khoury J, Kleindorfer D, Woo D, Schneider A, Alwell K, et al. Epidemiology of ischemic stroke in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:355–359. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donahue R, Abbott RD, Reed DM, Yano K. Postchallenge glucose concentration and coronary heart disease in men of japanese ancestry. Honolulu heart program. Diabetes. 1987;36:689–692. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.6.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The DECODE Study Group on behalf of the European Diabetes Epidemiology Group Glucose tolerance and cardiovascular mortality. Comparison of fasting and 2-hour diagnostic criteria. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:397–404. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levitan EB, Song Y, Ford ES, Liu S. Is non-diabetic hyperglycemia a risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2147–2155. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kernan WN, Inzucchi SE, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, Bravata DM, Horwitz RI. Insulin resistance and risk for stroke. Neurology. 2002;59:809–815. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rundek T, Gardener H, Xu Q, Goldberg RB, Wright CB, Boden-Albala B, et al. Insulin resistance and risk of ischemic stroke among nondiabetic individuals from the northern manhattan study. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiberg B, Sundstrom J, Zethelius B, Lind L. Insulin sensitivity measured by the euglycemic insulin clamp and proinsulin levels as predictors of stroke in elderly men. Diabetologia. 2009;52:90–96. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burchfiel CM, Curb JD, Rodriguez BL, Abbott RD, Chiu D, Yano K. Glucose intolerance and 22-year stroke incidence. The honolulu heart program. Stroke. 1994;25:951–957. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.5.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor RS, Brown A, Ebrahim S, Jolliffe J, Noorani H, Rees K, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2004;116:682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dansinger ML, Tatsioni A, Wong JB, Chung M, Balk EM. Meta-analysis: The effect of dietary counseling for weight loss. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:41–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boysen G, Krarup L-H, Zeng X, Oskedra A, Korv J, Andersen G, et al. Exstroke pilot trial of the effect of repeated instructions to improve physical activity after ischaemic stroke: A multinational randomized controlled clinical trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b2810. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with leisure intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Look AHEAD Research Group Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1566–1577. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dixon JB, O’Brien PE, Playfair J, Chapman L, Schachter LM, Skinner S, et al. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:316–323. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeMaria EJ. Bariatric surgery for morbid obesity. N Engl J Med. 2008;356:2176–2183. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct067019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]