Abstract

Amphiphilic block polypeptides can self-assemble into a range of nanostructures in solution, including micelles and vesicles. Our group has recently described the capacity of recombinant amphiphilic diblock copolypeptides to form highly stable micelles. In this report, we demonstrate the utility of protein nanoparticles to serve as a vehicle for controlled drug delivery. Drug-loaded micelles were produced by encapsulating dipyridamole as a model hydrophobic drug with anti-inflammatory activity. Murine studies confirmed the capacity of drug loaded protein micelles to limit in vivo recruitment of neutrophils in response to an inflammatory stimulus.

Keywords: polypeptides, protein micelles, hydrophobic drug, drug delivery

INTRODUCTION

Amphiphilic block copolymers are capable of solubilizing and encapsulating lipophilic compounds within a hydrophobic core, thereby, enhancing bioavailability and facilitating drug delivery.1–7 In aqueous solution, amphiphilic block copolymers composed of hydrophilic and hydrophobic chains can undergo self-assembly into polymeric micelles. It enables amphiphilic block copolymers to effectively serve as drug delivery vehicles.

Elastin-mimetic polypeptides, based on the pentameric repeat sequence (Val-Pro-Gly-Xaa-Gly), undergo thermal and pH responsive self-assembly in aqueous solution.8–11 Spontaneous phase separation of the polypeptide coincides with a conformational rearrangement of local secondary structure above a unique transition temperature (Tt) determined by the chemical identity of the fourth amino acid (Xaa) in the pentapeptide repeat.11,12 Recent studies have shown that self-assembled spherical nanoparticles can be derived from recombinant elastin-based amphiphilic block polypeptides for drug delivery application.13–17 However, the capacity of elastin-mimetic protein micelles to serve as vehicles for drug encapsulation has not been well defined.

We have recently reported the design of recombinant amphiphilic diblock polypeptides (ADP) derived from elastin-mimetic sequences that consist of a N-terminal hydrophilic block and a C-terminal hydrophobic block containing glutamic acid and tyrosine residues, respectively.18 We demonstrated that these polypeptides formed 50 nm diameter thermally responsive micellar nanoparticles that exhibited a spherical core-shell structure. By introducing multiple cysteine residues between the amphiphilic blocks, it was possible to obtain stable protein micelles through disulfide bond formation at the core-shell interface.16,18,19 Given the capacity to incorporate targeting ligands, cell membrane fusion sequences, receptor-activating peptides, fluorescent or chelating groups, significant opportunities exist for recombinant protein-based nanoparticles.

We describe herein the capacity of elastin-mimetic protein micelles to deliver dipyridamole (Persantine) as a model hydrophobic, anti-inflammatory compound.20–23 We postulated that the amphiphilic protein micelles would solubilize a water-insoluble compound in a manner similar to synthetic polymeric micelles.1–3,24 Moreover, we hypothesized that the presence of disulfide crosslinks at the core-shell interface would limit the release of the hydrophobic drug from the protein core. Both in vitro and in vivo studies of drug delivery are reported.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

All chemical reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Pittsburgh, PA) unless otherwise noted. Dipyridamole (DIP), Thioflavin-T and Zymosan A were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louse, MO). TALON metal affinity resin was purchased from BD Biosciences, Inc. Methods used to produce the diblock genes encoding the elastin-mimetic amphiphilic diblock polypeptide (ADP) including, [(VPGVG)(VPGEG)(VPGVG)(VPGEG)(VPGVG)]10 for the hydrophilic N-block ([Glu2]10) and [(IPGVG)2VPGYG(IPGVG)2]15 for the hydrophobic C-block ([Tyr]15), have been described previously.18 Expression of diblock synthetic genes with N-terminal His-tag sequence in E. coli expression strain, BL21(DE3), afforded recombinant elastin-mimetic diblock polypeptide in high yield (50 mg/L culture) when 1 mM IPTG was added. The purification was performed by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) from a cell lysate. Aqueous solutions of ADP were prepared from lyophilized specimens of purified protein polymer in distilled, deionized water or PBS at 4°C.

Preparation of elastin-mimetic protein micelles

Stock solutions of amphiphilic diblock copolypeptide (ADP) were prepared by dissolving the solid protein (1 mg/mL) in cold water. For preparation of protein micelles, the protein solution was diluted to 0.3 mg/mL in PBS and kept on ice for one hour. The solution was subsequently moved to a 25 °C water bath and incubated for 30 min. Micelles were stored under constant agitation at room temperature for 2 weeks and changes in micelle size and size distribution analyzed by dynamic light scattering (DynaPro, Protein Solutions).

Preparation and characterization of drug-loaded micelles

Dipyridamole was dissolved at pH 3 through addition of 1M HCl, followed by dropwise 1M NaOH to precipitate the compound at pH 7. The protein solution was added to the precipitated DIP solution in PBS and kept on ice for one hour then transferred to a water bath at 25 °C and incubated for 30 min. The drug containing micelle solution was then filtered through a 0.45 μm filter before characterization. Fluorescence spectra were obtained using PC1 photon counting spectrofluorometer (ISS, inc., champaign, IL). DIP and Thioflavin-T were used as hydrophobic fluorescent probes. The stock solution of the diblock copolymer (1.0 mg/mL) and DIP (4 μM) or Thioflavin-T (50 μM) were mixed together at various wt% ratios and incubated at 25°C for 30 min. Fluorescence spectra were recorded at an excitation wavelength of 415 nm and 450 nm for determination of the partition coefficient, respectively. UV-vis spectra of DIP-loaded micelles were recorded at specific time intervals on a Cary 50 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Varian, Inc.) in a 1 cm quartz cuvette.

Dynamic light scattering

Sample solutions were filtered through a 0.45 μm filter prior to DLS measurements that were carried out at a fixed scattering angle of 90° at 25 and 37°C, respectively. Samples were equilibrated at temperatures for 5 min before measuring. Size distribution and polydispersity of DIP-loaded micelles were analyzed by dynamic light scattering using a DynaPro.

Transmission electron microscopy

Solutions of DIP-loaded micelles were mixed with an equal amount of 1% PTA (phosphotungstic acid, adjusted with NaOH to pH 6.5). The mixed solution was placed onto a carbon support film on a copper grid for 5 min. Excess solution was wicked away and the grids were dried in a vacuum for 5 min. The samples were viewed with a JEOL 1400 TEM at a 80 kV accelerating voltage.

Determination of drug content and encapsulation efficiency

DIP-loaded micelles were incubated overnight at 4°C followed by the addition of 1 mM DTT to dissociate the micelles. The concentration of DIP was determined by UV spectroscopy at 415 nm with drug content and encapsulation efficiency calculated using the following equations:

| [1] |

| [2] |

In vitro drug release

A total of 10 mL of DIP-loaded micelles was placed in a dialysis bag (MWCO 10,000), which was then incubated in 50 mL PBS buffer at pH 7.4 and 37°C that was stirred at 250 rpm. The buffer solution was sampled at specific time intervals, DIP release monitored by UV spectroscopy, and the amount of released DIP calculated from a standard curve.

In vivo drug release

Male C57BL/6J mice (6–8 wks old, Jackson lab) received either 2 mL of PBS, a solution of protein micelles alone, DIP, or DIP-loaded micelles (7 % wt/wt) via intraperitoneal injection followed 30 minutes later by the administration of Zymosan A (1 mg/mL) IP. Four hours later, mice were euthanized with an overdose of isoflurane, peritoneal exudate cells collected, and total cell counts determined. For FACS analysis, anti-Gr1 (FITC) and anti-Mac1 (PE) were used (BD Pharmingen). Cell suspensions were analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACSort) and Gr1+Mac1+ neutrophil population quantified and recorded.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

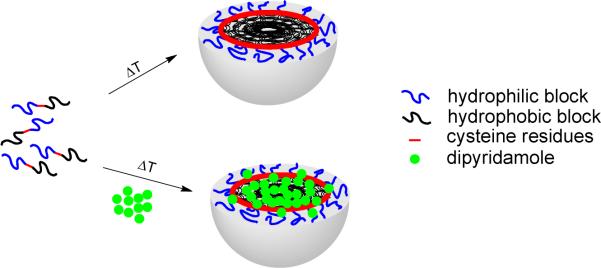

We synthesized a recombinant amphiphilic diblock polypeptide (ADP) consisting of a hydrophilic block of 10 pentapeptide repeats and a hydrophobic block of 15 repeats, which bear 20 glutamic acids ([Glu2]10) and 15 tyrosine residues ([Tyr]15), respectively18. Above a transition temperature (Tt ~10 °C), the recombinant diblock polypeptide self-assembles into micellar nanoparticles with disulfide crosslinks at the hydrophobic core-hydrophilic shell interface (Scheme 1). Protein micelles were stable when stored at room temperature in PBS with constant shaking for at least several weeks, as assessed by dynamic light scattering (DLS). When stored for up to 4 weeks under these conditions, only a negligibly small fraction of ~ 200 nm diameter micelles was observed, presumably due to micelle-micelle association.

Scheme 1.

Formation of thermally self-assembled elastin-mimetic protein micelles stabilized by disulfide crosslinks with encapsulation of a model hydrophobic drug, dipyridamole.

Preparation of drug-loaded protein micelle

Dipyridamole (2,2',2",2"'-{(4,8-dipiperidinopyrimino[5,4-d]pyrimidine-2,6-diyl)dinitrilo}tetraethanol, DIP) is known as a coronary vasodilator and a platelet inhibitor.20,25 In addition, DIP has been reported to have anti-inflammatory effects through inhibiting the adhesion of neutrophils to the vascular endothelium26 and scavenging of reactive oxygen species27. Its absorption is pH-dependent with decreased oral bioavailability at neutral or basic pH. Thus, encapsulation of DIP into delivery vehicles is necessary to improve bioavailability and achieve efficient delivery.

Dipyridamole has low solubility in water and displays physicochemical and fluorescent properties that are pH-dependant.22,23 In acidic solutions, its solubility is high because of the protonation both of aromatic nitrogens and piperidine nitrogens (pKa 5.7 and 12.5, respectively), but the quantum yield is low. At neutral pH, its water solubility decreases (10 μM), but the quantum yield is enhanced. In solutions at above pH 6, DIP precipitates as fine yellow particles.28

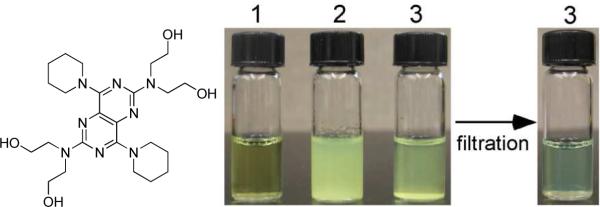

As shown in Figure 1, dipyridamole is soluble below pH 5, but as the pH is raised to neutral or 7.4 by dropwise addition of NaOH, DIP precipitates as fine particles with the production of larger particles over time. Upon addition of elastin-mimetic diblock polypeptides to the precipitated DIP solution followed by micellization at 25 °C, the precipitate rapidly disappears to yield a translucent yellow solution. The increased solubility of DIP in the presence of protein diblocks is consistent with that previously reported for the amphiphilic triblock copolymer, monomethoxy-capped poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate)-b-poly(2-diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate) (MPEG-DMADEA).28

Figure 1. Elastin-mimetic diblock protein polymers solubilize DIP.

1, DIP dissolves in an acidic (pH 3) aqueous solution; 2, but precipitates as yellow fine particles as the solution is neutralized (pH 7.4); 3, addition of diblock polypeptide (0.3 mg/mL) to the cooled solution at 4°C with subsequent warming to 25°C, with induction of micelle formation, enhances the solubility of DIP at pH 7.4. Residual DIP precipitates are removed by filtering solution 3 through a 0.45 μm syringe filter.

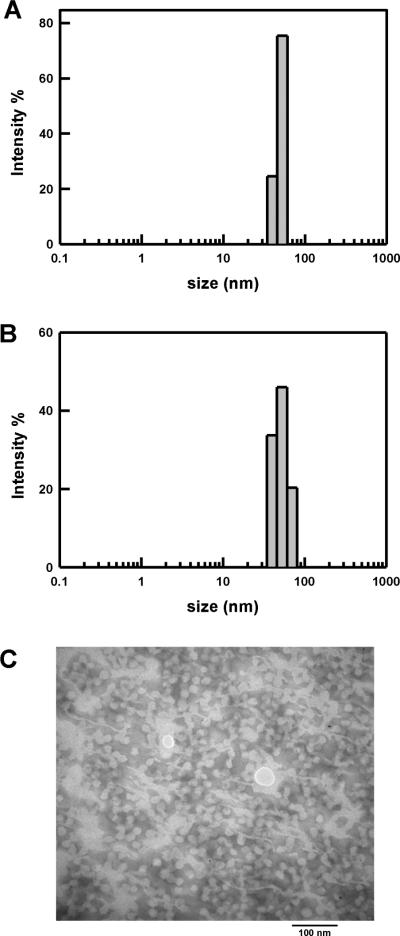

The average diameter of DIP-loaded micelles was 57 and 55 nm at 25 and 37 °C, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 2A,B). DIP-loaded micelles were slightly larger (~6 – 8 nm) as compared to empty micelles, which is consistent with reports for other drug loaded polymeric micelles.29,30 The DIP-loaded micelle prepared in aqueous solution was further characterized by transmission electron microscopy (Figure 2C). TEM imaging confirmed the morphology of DIP-loaded micelles that displayed uniform spheres ranged from 30 to 35 nm in average diameter, which was smaller than that determined by DLS. It is noted that TEM samples were prepared under dry state which can cause dehydration from the micelles and subsequently shrinkage of the micelles. The presence of hydrophobic molecule in preparing drug-loaded micelles had little influence on the self-assembly of elastin diblock polypeptides into spherical micelles as compared to that of empty micelles.

Table 1.

Size and Polydispersity of Elastin-mimetic Protein Micelles

Figure 2. Drug loaded elastin-mimetic protein polymers form nanoparticles.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements of empty (A) and DIP-loaded (B) micelles at 37°C. (C) Representative TEM image of DIP-loaded micelles.

Fluorescence spectra and partitioning of hydrophobic drug

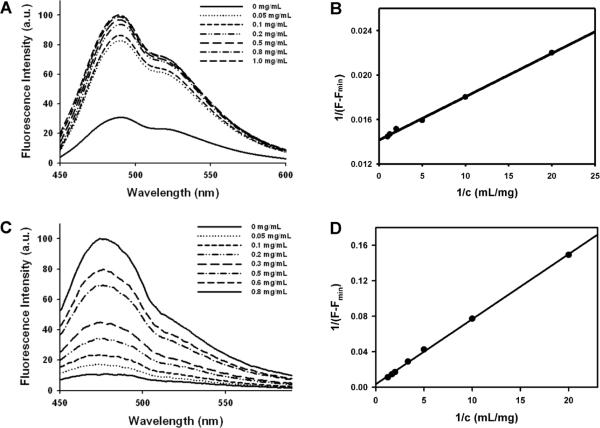

Fluorescence spectroscopy was employed to investigate the ability of protein nanoparticles to encapsulate the hydrophobic drug within the micelle core. DIP was mixed with the protein polymer in PBS on ice and subsequently warmed to 25 °C to induce micellization of the polypeptide. Fluorescence spectra of DIP is presented in Figure 3A as a function of diblock concentration, with emission intensity at 490 nm increasing with protein polymer concentration. Similar results were also observed for 1,8-ANS18 and thioflavin-T (Figure 3C). These results suggest that the drug is effectively localized within the micelle core presumably due to the C-terminal polymeric block that is hydrophobic and displays limited chain mobility. Similar fluorescence spectral behavior for DIP at pH 7.4 has been noted for PDLLA-b-PDMAEMA diblock copolymers.31

Figure 3. Dipyridamole partitions within elastin-mimetic protein micelles.

Fluorescence spectra of DIP (A) and thioflavin-T (C) measured in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) at 415 and 450 nm in the presence of increasing diblock polypeptide concentration. The partition coefficient of DIP (B) and thioflavin-T (D) in an elastin-mimetic micellar solution (pH 7.4) was determined by plotting 1/(F- Fmin) vs 1/c.

A plot of 1/c as a function of 1/(F-Fmin) can be used to calculate the partition coefficient (K) of DIP in a micellar solution28,31,32

| [3] |

where Fmin and Fmax represent the fluorescence intensity of DIP solutions of increasing micelle concentration, c, ρ is the density of the micelle core (1 g·cm-3), and α is the core forming fraction of the protein polymer.

The K for DIP in elastin-mimetic protein micelles was 6.1 × 104, which is comparable to reported values (103 – 104) of DIP for solutions of a number of synthetic block copolymers.28,31,32 As anticipated, the partition coefficients of 1,8-ANS (4.0 × 102) and thioflavin-T (1 × 103), which are hydrophobic small molecules that carry a charged group were lower than that of DIP (Figure 3D).

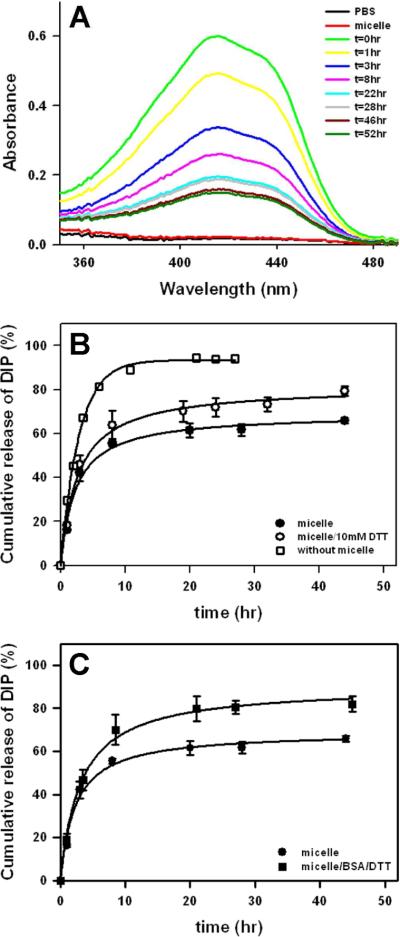

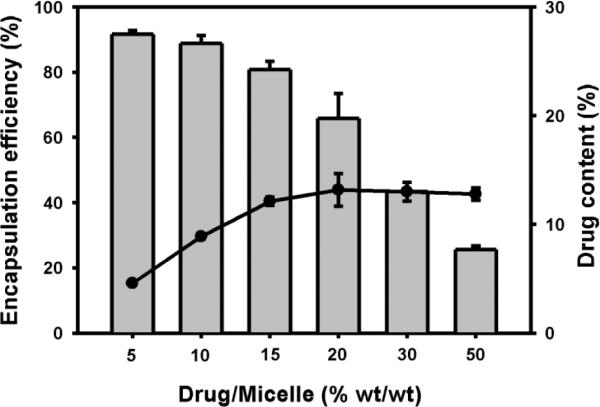

In vitro drug release

The amount of encapsulated DIP was determined by UV spectroscopy (absorption max. 450 nm) by lowering the solution temperature below the inverse transition temperature of the protein diblock followed by the addition of DTT, which lead to micelle dissociation. In a range of 15 – 30% wt/wt (DIP/micelle), drug loading of 11 – 12% wt/wt (33 – 36 μg/mL) was observed (Figure 4). Considering the low solubility of DIP in water (~0.5 μg/mL), this corresponds to a 60 – 70 fold increase in drug solubility.

Figure 4. Dipyridamole content and encapsulation efficiency in elastin-mimetic protein micelles.

Drug content (line) and encapsulation efficiency (bar) was determined as a function of drug/micelle (% wt/wt) (n=3) after measurement of DIP following DTT-induced micelle dissolution.

Drug release studies were initially conducted by monitoring the level of DIP remaining within micelles (Figure 5A). Release of DIP was most rapid during the first 8 hrs and slowed thereafter, suggesting that the remaining compound was stably associated within the protein micelles. As a complementary approach, conventional dialysis was also performed to characterize DIP release rates in a system consisting of 10% wt/wt DIP in 0.3 mg/mL micelle solution. Rapid initial release of DIP within 3 hr was noted, followed by extended release over a 40 hr period (Figure 5B). As illustrated in Scheme 1, protein micelles are crosslinked through disulfide bond formation at the core-shell interface. Addition of 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) cleaves the disulfide crosslinks, which increased DIP release rate. In a previous study, we observed that the addition of BSA and DTT to micelle solutions caused a significant increase in micelle size.18 Indeed, after 3 hrs the release of DIP from protein micelles was faster in the presence of BSA and DTT (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Release of dipyridamole from elastin-mimetic micelles.

(A) UV-visible spectra of DIP-loaded micelles were acquired at specific time intervals after incubation in PBS buffer at pH 7.4 and 37°C and the amount of released DIP calculated from a standard curve. (B) DIP release was determined with (◯) or without (●) exposure of micelles to 10 mM DTT at 37 °C (n=3). Diffusion of DIP in the absence of micelles (pH 3) from the dialysate chamber was also measured (□). (C) DIP release from the protein micelles was also assessed in the presence of BSA (3 mg/mL) and 1 mM DTT (■).

We believe the mechanism of drug release from amphiphilic elastin-mimetic micelle as follows. First, hydrophobic drug precipitated at neutral pH is solubilized by the addition of amphiphilic diblock polypeptides. Despite localization of the drug within a hydrophobic micellar core, the presence of a surrounding negatively charged shell and an acidic microenvironment, leads to protonation of the drug due to a local increment in pKa, which has been observed in other negatively charged drug releasing micelle systems.23 Thus, given induced charging of dipyridamole located at block interface, drug partition is shifted to the hydrophilic shell and the external aqueous solution. This results in an increased release rate while remaining DIP molecules are associated within the hydrophobic core. Indeed, the release profile was re-plotted as a function of the square root of time and appears to follow the Higuchi's diffusion model (Figure S1).33 The profile exhibited slightly slower release to ~15% at the 1 hr time point. This is attributed to drug diffusion within the micelle, presumably from the hydrophobic core to the hydrophilic shell. Similar kinetics observed for DIP release from micelles has been shown for pH-responsive diblock copolymer (PMPC-b-PDPA) micelles.32 Upon approaching to the hydrophilic shell region, release kinetics follow a diffusion-controlled release mechanism.

In a separate experiment, we changed the length of hydrophobic block from 15, [Tyr]15 to 12, [Tyr]12 repeats, but with same length of hydrophilic block, which formed micellar nanoparticles in of almost the same size range.18 For protein micelles with short hydrophobic block, the amount of DIP released within a 9 hr period was approximately 75%, while 60% for protein micelle with longer hydrophobic block (Figure S2). This result shows that protein micelles with longer hydrophobic block released drugs more slowly than micelles with shorter hydrophobic block. The difference in release rate may be attributed to the more densely packed micelle cores formed by longer hydrophobic blocks, subsequently increasing interactions of the hydrophobic drug with hydrophobic core.”

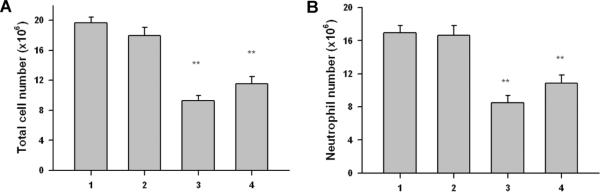

In vivo drug release in peritoneal cavity model

Dipyridamole displays anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting the adhesion of neutrophils to the vascular endothelium.26,27 The capacity of drug loaded micelles to exert an anti-inflammatory effect was investigated using a Zymosan-induced murine model of peritonitis.34 Drug-loaded micelles were prepared at a DIP concentration of 21 μg/mL. C57BL/6 mice received DIP alone and the DIP-loaded micelles followed by Zymosan A (1 mg/mL, IP) 30 min later. Peritoneal cells were collected after 4 hrs and FACS used to quantify neutrophils or total cell number (Gr1+Mac1+PMNs) (**p < 0.01). Same protocol was carried out for PBS buffer and empty protein micelles as controls. Neither micelles alone nor PBS influenced the development of an inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 7). DIP-loaded micelles significantly reduced total cell number and neutrophil infiltration.

CONCLUSION

Recombinant amphiphilic elastin-mimetic protein micelles demonstrate the capacity to solubilization, encapsulation, and release hydrophobic drugs. Dipyridamole, a lipophilic compound with anti-inflammatory activity, can be solubilized at pH 7.4 and encapsulated within self-assembled protein micelles. The release of DIP from these micelles was accelerated in the presence of a reducing agent and BSA and DIP-loaded micelles significantly reduced the development of an inflammatory cell infiltrate in vivo. Future studies will explore the ability of targeting ligands, cell membrane fusion sequences, and receptor-activating peptides to further enhance the the ability of recombnant protein micelles to serve as effective targeted drug delivery vehicles.

Supplementary Material

Figure 6. Delivery of DIP from the elastin-mimetic protein micelles in vivo.

The ability of DIP and DIP-loaded micelles to limit total cell (A) and neutrophil (B) infiltration was assessed in a murine model of zymosan A-induced peritonitis (n=5–7, ** p<0.01 compared with control group). 1, PBS; 2, protein micelle; 3, DIP; 4, DIP-loaded micelle.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the NIH and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. Use of TEM was supported by the Wyss Institute of Biologically Inspired Engineering of Harvard.

REFERENCES

- (1).Gaucher G, Dufresne MH, Sant VP, Kang N, Maysinger D, Leroux JC. J. Control. Release. 2005;109(1–3):169–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kataoka K, Harada A, Nagasaki Y. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2001;47(1):113–31. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Adams ML, Lavasanifar A, Kwon GS. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003;92(7):1343–55. doi: 10.1002/jps.10397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Soo PL, Luo LB, Maysinger D, Eisenberg A. Langmuir. 2002;18(25):9996–10004. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kabanov AV, Nazarova IR, Astafieva IV, Batrakova EV, Alakhov VY, Yaroslavov AA, Kabanov VA. Macromolecules. 1995;28(7):2303–2314. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kwon G, Naito M, Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y, Kataoka K. J. Control. Release. 1997;48(2–3):195–201. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Velluto D, Demurtas D, Hubbell JA. Mol. Pharm. 2008;5(4):632–42. doi: 10.1021/mp7001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Girotti A, Reguera J, Arias FJ, Alonso M, Testera AM, Rodriguez-Cabello JC. Macromolecules. 2004;37(9):3396–3400. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Urry DW, Gowda DC, Parker TM, Luan CH, Reid MC, Harris CM, Pattanaik A, Harris RD. Biopolymers. 1992;32(9):1243–1250. doi: 10.1002/bip.360320913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Urry DW, Luan CH, Parker TM, Gowda DC, Prasad KU, Reid MC, Safavy A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113(11):4346–4348. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Urry DW. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 1993;32(6):819–841. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Yamaoka T, Tamura T, Seto Y, Tada T, Kunugi S, Tirrell DA. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4(6):1680–1685. doi: 10.1021/bm034120l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lee TAT, Cooper A, Apkarian RP, Conticello VP. Adv. Mater. 2000;12(15):1105–1110. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Dreher MR, Simnick AJ, Fischer K, Smith RJ, Patel A, Schmidt M, Chilkoti A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130(2):687–694. doi: 10.1021/ja0764862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Sallach RE, Wei M, Biswas N, Conticello VP, Lecommandoux S, Dluhy RA, Chaikof EL. J. Am. Chem. So.c. 2006;128(36):12014–12019. doi: 10.1021/ja0638509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Fujita Y, Mie M, Kobatake E. Biomaterials. 2009;30(20):3450–3457. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kim W, Chaikof EL. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2010;62(15):1468–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kim W, Thevenot J, Ibarboure E, Lecommandoux S, Chaikof EL. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2010;49(25):4257–4260. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Science. 2001;294:1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chakrabarti S, Freedman JE. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2008;48(4–6):143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Weyrich AS, Denis MM, Kuhlmann-Eyre JR, Spencer ED, Dixon DA, Marathe GK, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM. Circulation. 2005;111(5):633–42. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154607.90506.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Nassar PM, Almeida LE, Tabak M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1328(2):140–50. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Borissevitch IE, Borges CP, Yushmanov VE, Tabak M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1238(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00112-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Kim D, Lee ES, Oh KT, Gao ZG, Bae YH. Small. 2008;4(11):2043–50. doi: 10.1002/smll.200701275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kim HH, Liao JK. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28(3):s39–42. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hallevi H, Hazan-Halevy I, Paran E. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007;14(9):1002–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Iuliano L, Pedersen JZ, Rotilio G, Ferro D, Violi F. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995;18(2):239–47. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)e0123-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Tang Y, Liu SY, Armes SP, Billingham NC. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4(6):1636–45. doi: 10.1021/bm030026t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Xing L, Mattice WL. Langmuir. 1998;14(15):4074–4080. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Li Y, Pan S, Zhang W, Du Z. Nanotechnology. 2009;20(6):065104. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/6/065104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Karanikolopoulos N, Zamurovic M, Pitsikalis M, Hadjichristidis N. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(2):430–438. doi: 10.1021/bm901151g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Giacomelli C, Le Men L, Borsali R, Lai-Kee-Him J, Brisson A, Armes SP, Lewis AL. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(3):817–828. doi: 10.1021/bm0508921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Higuchi T. J Pharm. Sci. 1961;50:874–875. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600501018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Cash JL, White GE, Greaves DR. Method Enzymol. 2009;461:379–396. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)05417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.