Abstract

The γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor is the major transmitter-gated inhibitory channel in the central nervous system. The receptor is a target for anesthetics, anticonvulsants, anxiolytics and sedatives whose actions facilitate the flow of chloride ions through the channel and enhance the inhibitory tone in the brain. Both the kinetic and structural aspects of the actions of modulators of the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor are of great importance to understanding the molecular mechanisms of general anesthesia. In this review, we describe the structural rearrangements that take place in the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor during channel activation and modulation, focusing on data obtained using voltage-clamp fluorometry. Voltage-clamp fluorometry entails the binding of an environmentally-sensitive fluorophore molecule to a site of interest in the receptor, and measurement of changes in the fluorescence signal resulting from activation- or modulation-elicited structural changes. Detailed investigations can provide a map of structural changes that underlie or accompany the functional effects of modulators.

Organization and the static structure of the GABAA receptor

The γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor constitutes the predominant fast inhibitory force in the central nervous system. The receptor responds to the binding of two synaptically-released or ambient γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) molecules with a conformational change in the associated channel, opening the channel gate for chloride and other monovalent anions. In mature neurons, the intracellular chloride concentration is low and the chloride reversal potential is negative to the threshold for action potentials. Thus, GABAA receptor activation results in an influx of anions, leading to hyperpolarization of the cell or reduction of the effects of excitatory channels.

The receptor is a target for numerous anesthetics, anticonvulsants, anxiolytics, and sedatives, which act by facilitating chloride flow through the channel 1–3. Kinetic studies of ionic currents have shown that the drugs act by enhancing the open probability of the channel by stabilizing the open state of the channel and/or destabilizing the closed state. It has been proposed that the drugs act to enhance affinity to GABA (e.g., benzodiazepines 4) or gating efficacy (e.g., neurosteroids 5), although the precise molecular mechanisms of action are not fully understood.

The GABAA receptor is a pentameric membrane protein. To date, nineteen GABAA receptor subunits have been cloned. These are: α1–α6, β1–β3, γ1–γ3, δ, ε, π, θ, and ρ1–ρ3 6. Native receptors are heteromeric, typically containing two α subunits, two β subunits, and a single γ, δ, ε, π, or θ. The previously called GABA type C receptors are homo- and heterooligomers, formed of ρ1, ρ2, or ρ3 subunits. The expression of the subunits is regionally and developmentally regulated, so that receptors with differing subunit compositions - and differing physiological and pharmacological properties - are expressed throughout the nervous system. The effects of subunit composition on channel properties have been thoroughly described in publications spanning the past two decades (e.g., 7–11).

Each of the five homologous subunits has a large N-terminal extracellular domain. This is followed by four membrane-spanning regions and a short C-terminal tail extending to the outside of the cell 12 (fig. 1). A mature subunit is 50–60 kDa in molecular weight (~450 amino acid residues). The transmitter (GABA) binding sites are located in the extracellular region at the interfaces between the β and α subunits where groups of residues from regions distant to each other in terms of primary structure form a pocket lined with loop-like structures (fig. 1). The β subunit contributes the primary (or, so-called "+") side, with Loops A (residues β2W92-D101), B (β2Y157 to T160), and C (β2T202 to S209), whereas the α subunit forms the complementary (so-called, "−") side, with Loops D (α1F64 to S68), E (α1R119 to M130), and F (α1V180 to G194). We note that the beginning and ending residues in each loop can be somewhat arbitrary and are based on the transmitter binding site in the homologous nicotinic receptor 13. A homologous interface between the α and γ subunits is involved in the binding of benzodiazepines 14. The pore of the ion channel is lined by the M2 domains (second membrane-spanning segments) from each of the five subunits (fig. 1), and the channel gate is formed by residues near the intracellular end of the channel 15. The transmembrane region also contains interaction sites for neurosteroids, etomidate, and volatile anesthetics such as halothane and isoflurane 16–18.

Figure 1.

Organization of the γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor. (A) A subunit of the GABAA receptor contains a long aminoterminal region, followed by three transmembrane domains (M1–M3), a long cytoplasmic loop, the fourth membrane-spanning segment (M4), and a short carboxyterminal domain. The M2 domain is a major contributor to the central pore. (B) Topology of a subunit showing the region of the subunit contributing to the transmitter binding site (G). The neurosteroid and etomidate binding sites are located in the membrane-spanning domains. A functional receptor is formed of five homologous subunits organized around a central Cl− conducting pore. (C) A top view (cross section) of the receptor demonstrating the principal locations of the transmitter binding sites (G) at the β-α subunit interfaces. The β subunit contributes the primary (or, "+") side and the α subunit contributes the complementary (or, "−") side of the transmitter binding site. The receptor contains two pairs of β and α subunits. The fifth subunit (blue in the figure) may be a third α or β subunit, or a γ, δ, or ε subunit. The nature of the subunit in the fifth position can have a strong effect on the functional properties of the receptor. Benzodiazepines interact with a site at the α-γ subunit interface. Some receptors (e.g., ρ subunit-containing) form as homopentamers having the same major structural features.

Channel activation

The binding of agonist to the extracellular domain of the receptor leads to conformational changes that result in the opening of the channel gate, some 60 Å away 19. In the related nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, the binding of transmitter leads to movement in Loop C which caps the binding pocket and is believed to constitute the physical rearrangement that initiates propagation of structural changes to channel gate and underlies increased affinity to the transmitter of the open channel 20. Similar rearrangements likely take place in the GABAA receptor.

Recent studies have introduced voltage-clamp fluorometry (also called: site-specific fluorescence), an approach in which fluorescence changes, resulting from changes in the microenvironment surrounding a fluorophore upon channel activation are employed to study changes in receptor structure. The fluorophore is an environmentally-sensitive probe that responds with altered quantum yield, that is, altered fluorescence intensity during constant illumination to changes in the polarity of the environment. The probe is covalently attached to a cysteine residue engineered in the site of interest in the receptor. If the environment around the probe changes during channel activation or modulation, the intensity of the fluorescence signal changes. The change in fluorescence intensity will be denoted as ΔF in this article. It is usually expressed relative to the baseline signal, so ΔF = [(fluorescence signal in test condition)-(fluorescence signal in control condition)]/(fluorescence in control condition).

When coupled with electrophysiological recordings this approach allows to simultaneously record functional (current flow) and the associated or underlying structural (fluorescence) responses from the receptor. The advantage of voltage-clamp fluorometry is that it has the potential to reveal changes in receptor structure (conformation) that are not seen in the membrane current response. One particular example that we will discuss is the case of inhibitory steroids acting on the ρ1 GABAA receptor: in all cases the membrane current is reduced, but the associated conformational changes in the receptor differ 21.

This approach was initially employed in studies of structural changes associated with gating of potassium channels 22, but has more recently been used to study structural dynamics in transmitter-gated ion channels such as the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor 23,24, glycine receptor 25,26, and the GABAA receptor 21,27–30. In the following sections we review the current state of knowledge on the structural dynamics of the GABAA receptor.

Criteria for observation of fluorescence changes

Observation of fluorescence changes is dependent on a number of criteria. These are: successful labelling of the engineered cysteine residue in the region of interest, changes in the polarity of the environment surrounding the fluorescent probe, and a lack of significant labelling of endogenous cysteines that would increase background fluorescence signal or produce an activation-dependent signal of their own. We will now examine each of these criteria separately.

The maleimide- (e.g., Alexa 546 maleimide, A5m) or methanethiosulfonate-based (MTS) fluorescent probes (e.g., sulforhodamine methanethiosulfonate) covalently bind to the cysteine residue (fig. 2). Cysteines most likely to be successfully labelled are at the water-accessible surface of the protein where, due to ionization of the side chain, the reaction rate is significantly higher 31. In addition, cysteine residues located in the hydrophobic intraprotein core may be inaccessible to the probe. The intrinsic reaction rate of MTS derivatives with thiols is on the order of 105M−1s−1 32. Although the reaction rates with engineered cysteine residues in proteins can be significantly less depending on the location and availability of the residue, complete modification in the experimental setting is typically achieved in seconds or minutes.

Figure 2.

Voltage-clamp fluorometry. (A) Structures of two commonly-used fluorophores: Alexa 546 maleimide (Alexa 546) and tetramethylrhodamine maleimide (TMRM). For comparison, structure of the transmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is shown next to the fluorophores. (B) The maleimide group of the fluorophore binds to the thiol group of the cysteine residue via a maleimide-thiol reaction to form a carbon-sulfur bond. (C) Schematic of the experimental setup. The receptors are expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The oocyte is placed in a custom-made chamber exposing a portion of the membrane through a 0.8 mm pinhole to the lower compartment. The agonist and modulators are applied through the lower compartment. The oocyte is impaled in the top compartment. Two-electrode voltage-clamp is used to record the currents. The chamber is placed into a Petri dish and an inverted microscope, equipped with the appropriate filters, is used to illuminate the oocyte and collect fluorescence.

Successful binding of the probe to the receptor can often be determined from changes in functional properties, e.g., a shift in the agonist concentration-response curve following incubation with the fluorophore. In the absence of a functional effect, an activation- or modulation-elicited fluorescence change (ΔF) itself can serve as proof of successful labelling of the receptor. The absence of a fluorescence change is more difficult to interpret. Either lack of labelling or lack of measurable environmental changes around the fluorophore will result in a situation where no ΔF is observed.

It is important to remember that the fluorophore senses the polarity of environment. Thus the structure of the receptor surrounding the fluorophore may change, but unless this leads to changes in the polarity of the environment, the fluorescence signal does not change. An increase in fluorescence intensity is associated with the environment around the fluorophore becoming more hydrophobic. The magnitude of ΔF, however, does not contain information about the physical distance travelled or the origin of movement, i.e., whether the surrounding residues move relative to the static fluorophore or whether the residue linked to fluorophore moves relative to a static environment. We note that conformational changes altering proximity or spatial relation to a protein side chain with quenching activity (e.g., aromatic residues) could also result in changes in fluorescence intensity.

Fluorescence experiments are conducted on receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. A schematic of a recording setup that combines fluorescence measurements and two-electrode voltage clamp is shown in figure 2.

Control experiments on cells expressing wild-type (α1β2, α1β2γ2, or ρ1) GABAA receptors incubated with A5m or sulforhodamine methanethiosulfonate do not demonstrate changes in the GABA concentration-response relationship or an activation-dependent ΔF 27,29,30,33. The extracellular domain of the GABAA receptor contains 10 native cysteine residues (two in each subunit of the pentameric receptor). These residues are crosslinked to each other to form the characteristic intrasubunit disulfide bond at the interface between the transmitter-binding extracellular domain and the membrane-spanning region, a necessary precondition for functionality in Cys-loop receptors 34. On the extracellular side of the membrane, in the linker between the second and third membrane-spanning regions, are five cysteine residues (one per subunit), but these are apparently not labeled by the commonly used fluorophores. Additional cysteine residues are found in the transmembrane segments and in the long cytoplasmic loop between the third and fourth membrane-spanning segments. These are likely inaccessible to the fluorophores that are applied to the extracellular medium.

To date, voltage-clamp fluorometry has focused on the extracellular region at or near the transmitter binding site, and the outer end of the second membrane-spanning domain. In the extracellular domain of the α1 subunit, cysteine mutations to the E122 and L127 (both in Loop E), and R186 (Loop F) sites have been productively labeled 29,30,33. No ΔF was observed from Loop F residues A181 to S185 in the α1 subunit 29. Labeling of the α1 subunit Loop C residues Q203, S204, and E208 with numerous fluorophores has not been productive 29. In the extracellular region of the β2 subunit, ΔF signals have been observed from L125 (Loop E), and I180 (Loop F) residues. No ΔF was observed from S200, T201, G202, or S203 sites (Loop C). In the γ2 subunit, labeling at the S195 site (Loop F) produces a fluorescence change during channel activation. However, labeling of neighboring sites (R194, W196, or R197) has been unproductive.

In the homooligomeric ρ1 receptor, Chang and Weiss27 found that the L166 (Loop E, homologous to α1L127 site), S66 (at the subunit-subunit interface), and Y241 sites (Loop C) respond to agonist applications with fluorescence change. In Loop F of the ρ1 subunit, Khatri et al. 28 and Zhang et al. 35 found that sites K210, K211, L216, K217, T218, E220, R221, I222, S223, L224, Q226, F227 and I229 exhibit agonist-induced fluorescence changes. Sites that have been successfully labeled in the extracellular domain of the GABAA receptor are shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

The extracellular domain of the γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor portraying the side view at the β2-α1 subunit interface. The β subunit is shown in cyan, the α subunit is shown in pink. The residues which respond with fluorescence change (ΔF) to applications of agonist are shown in blue in the β subunit, and in red in the α subunit. The numbering pertains to the rat α1 and β2 subunits. Sites for which homologous residues in the ρ1 receptor demonstrate ΔF are shown in gray. For those residues, the numbering derives from the human ρ1 sequence. The transmitter binds in the intersubunit cavity near the residues Y241 and L127. A summary of data from fluorescence recordings from these sites is given in table 1. In fluorescence recordings the residues are mutated to cysteines which are then labelled with environmentally-sensitive fluorescent probes. For size comparison, a commonly-used fluorophore, Alexa 546 maleimide, is shown next to the receptor structure.

In the second membrane-spanning domain of the β2 subunit, the 24' residue (numbering starts from the intracellular side and is based on consensus sequence with the related nicotinic receptor 36; K274) can be successfully labeled 29,37. In the α1 subunit, labeling of the N274 site (N20' residue in M2) produces ΔF in the presence of agonists. The sites from 19' to 27' do not exhibit ΔF 29. In the γ2 subunit, labeling of the P23' site (P288C), but not 20' or 24' sites, results in productive labeling. A full list of sites productively labelled is given in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Fluorescence Signals from the GABAA Receptor.

| Location | Labelled residue |

Receptor | Activator | Fluorophore | ΔF | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loop C | ρ1Y241C | ρ1 | GABA, 3-APMPA, 3-APA | A5m | ↑ | 21,27 |

| Loop E | α1E122C | α1β2 | GABA | A5m, MTSR, TMRM | ↓ | 33 |

| Loop E | α1E122C | α1β2 | gabazine | TMRM | ↑ | 33 |

| Loop E | α1E122C | α1β2γ2 | GABA | TMRM | ↓ | 33 |

| Loop E | α1L127C | α1β2 | GABA | A5m, MTSR, TMRM | ↑ | 33 |

| Loop E | α1L127C | α1β2 | PB* | TMRM | ↓ | 37 |

| Loop E | α1L127C | α1β2γ2 | GABA | A5m, TMRM | ↑ | 30,37 |

| Loop E | α1L127C | α1β2γ2 | gabazine | TMRM | ↓ | 37 |

| Loop E | α1L127C | α1β2γ2 | gabazine | A5m | ↑ | 30 |

| Loop E | ρ1L166C | ρ1 | GABA, TACA | A5m | ↑ | 21,27 |

| Loop E | ρ1L166C | ρ1 | 3-APMPA, 3-APA | A5m | ↓ | 27 |

| Loop F | α1R186C | α1β2 | GABA, β-alanine, gabazine | MTSR | ↓ | 29 |

| Loop F | β2I180C | α1β2 | GABA, β-alanine, gabazine | MTSTAMRA | ↓ | 29 |

| Loop F | γ2S195C | α1β2γ2 | GABA, β-alanine | TMRM | ↓ | 29 |

| Loop F | γ2S195C | α1β2γ2 | GABA+diazepam** | TMRM | ↑ | 29 |

| Loop F | ρ1K210C | ρ1 | GABA | MTSR | ↑ | 35 |

| Loop F | ρ1K211C | ρ1 | GABA | MTSR | ↑ | 35 |

| Loop F | ρ1L216C | ρ1 | GABA, isoguvacine, I4AA, 3-APA | A5m | ↑ | 28 |

| Loop F | ρ1L216C | ρ1 | GABA, 3-APMPA | MTSR | ↓ | 35 |

| Loop F | ρ1K217C | ρ1 | GABA, isoguvacine, I4AA, 3-APA, 3-APMPA | A5m, MTSR | ↓ | 28,35 |

| Loop F | ρ1T218C | ρ1 | GABA, isoguvacine, I4AA, 3-APA | A5m | ↑ | 28 |

| Loop F | ρ1T218C | ρ1 | GABA, 3-APMPA | MTSR | ↓ | 35 |

| Loop F | ρ1E220C | ρ1 | GABA | A5m, MTSR | ↓ | 28,35 |

| Loop F | ρ1R221C | ρ1 | GABA | A5m | ↑ | 28 |

| Loop F | ρ1I222C | ρ1 | GABA | A5m | ↑ | 28 |

| Loop F | ρ1I222C | ρ1 | GABA, 3-APMPA | MTSR | ↓ | 35 |

| Loop F | ρ1S223C | ρ1 | GABA, isoguvacine, I4AA, 3-APA | A5m | ↓ | 28 |

| Loop F | ρ1L224C | ρ1 | GABA | A5m | ↓ | 28 |

| Loop F | ρ1Q226C | ρ1 | GABA | A5m | ↓ | 28 |

| Loop F | ρ1F227C | ρ1 | GABA | A5m | ↓ | 28 |

| Loop F | ρ1I229C | ρ1 | GABA, isoguvacine, TACA, 3-APA | A5m | ↑ | 28 |

| ECD | ρ1S66C | ρ1 | GABA, TACA | A5m | ↓ | 21,27 |

| ECD | ρ1S66C | ρ1 | 3-APMPA | A5m | ↓ | 21,27 |

| 20' of M2 | α1N274C | α1β2 | GABA, β-alanine | TMRM | ↑ | 29 |

| 20' of M2 | α1N274C | α1β2γ2 | GABA, β-alanine | TMRM | ↑ | 29 |

| 20' of M2 | α1N274C | α1β2γ2 | GABA+diazepam*** | TMRM | ↓ | 29 |

| 24' of M2 | β2K274C | α1β2 | GABA, β-alanine | MTSR | ↑ | 29 |

| 24' of M2 | β2K274C | α1β2 | gabazine | MTSR | ↓ | 29 |

| 24' of M2 | β2K274C | α1β2γ2 | GABA | TMRM | ↓ | 37 |

| 24' of M2 | β2K274C | α1β2γ2 | PB | TMRM | ↑ | 37 |

| 24' of M2 | β2K274C | α1β2γ2 | β-alanine | MTSR | ↑ | 29 |

| 23' of M2 | γ2P288C | α1β2γ2 | GABA, β-alanine | TMRM | ↓ | 29 |

The table gives a list of residues at which changes in fluorescence signal have been observed. The columns give the labeled residue, its location in receptor, receptor subunit composition, ligands used to activate or modulate the receptor, the fluorophore, a direction of ΔF, and the reference. GABA, β-alanine and TACA are full agonists of the GABAA receptor. Isoguvacine and I4AA are partial agonists considered to act at the transmitter binding site. PB activates the receptor by interacting with an allosteric binding site. Gabazine is a competitive inhibitor of the αβ and αβγ receptor. 3-APA and 3-APMPA are competitive inhibitors of the ρ1 receptor. The ρ1L166 site is homologous to the L127 residue in the α1 subunit. ECD = extracellular domain; M2 = second membrane-spanning domain.

activating concentration (300–800 µM) PB;

100 µM diazepam;

10 µM diazepam.

A5m = Alexa 546 maleimide; 3-APMPA = 3-aminopropyl-(methyl)phosphinic acid; 3-APA = 3-aminopropylphosphonic acid; GABA = γ-aminobutyric acid; I4AA = imidazole-4-acetic acid; MTSR = sulforhodamine methanethiosulfonate; MTSTAMRA = 2-((5(6)-tetramethylrhodamine)carboxylamino)ethyl methanethiosulfonate = PB, pentobarbital; TACA = trans-aminocrotonic acid; TMRM = tetramethylrhodamine maleimide.

Thus, productive labeling has been moderately successful, with less than half of all tested sites demonstrating drug-induced ΔF. It should also be noted that ΔF is sometimes observed with one fluorophore but not another, probably resulting from differences in the precise positioning of the bound fluorophore molecule. Overall, it appears that the ρ1 receptor may be more amenable to productive labeling, likely due to its homooligomeric nature resulting in the binding of five molecules of the fluorophore per receptor and a larger fluorescence signal. The magnitude of ΔF is expressed in % in relation to to the baseline fluorescence level. A typical response is an increase or decrease of up to 4 %, while higher ΔF values are common in the homooligomeric ρ1 receptor.

Movements during channel activation by orthosteric ligands

Receptors productively labelled with a fluorophore demonstrate a change in fluorescence intensity upon exposure to the transmitter. An increase in fluorescence intensity is associated with the environment surrounding the fluorophore becoming less polar, while a decrease in fluorescence indicates that the environment has become more polar. A change in fluorescence does not reveal whether the protein region around the fluorophore moved or the fluorophore itself moved, due to dislocation of the residue to which it is linked. Thus, a ΔF is an indication of a general structural change in the region where the fluorophore is located. The sign of ΔF can be important when comparing the actions of different ligands which may cause distinct structural rearrangements. The magnitude of the change is important in that increased signal to noise ratio improves signal detection, however, the magnitude of ΔF cannot be used as an indication of the extent or distance of movement. Overall, the approach is most useful when comparing the effects of different drugs to determine whether a structural change has taken place with little regard concerning the nature or extent of movement.

Sites near the transmitter binding site show ligand-induced ΔF. A sample recording is shown in figure 4A. Several important points can be made on the basis of published work. First, the time course of development of the ΔF signal from the GABAA receptor is in most cases similar to the time course of current rise. This is an indication that ΔF is associated with channel activation. However, in some cases, a disconnect between the current and ΔF time courses has been noted. In the ρ1K217C (Loop F) receptor labelled with sulforhodamine methanethiosulfonate, Zhang et al. 35 observed that the fluorescence signal developed more rapidly than the current response. They proposed that the ΔF from the ρ1K217C receptor reports the agonist binding event rather than channel gating. Overall, however, the solution exchange rates in the oocyte system are too slow to resolve fast steps of channel activation.

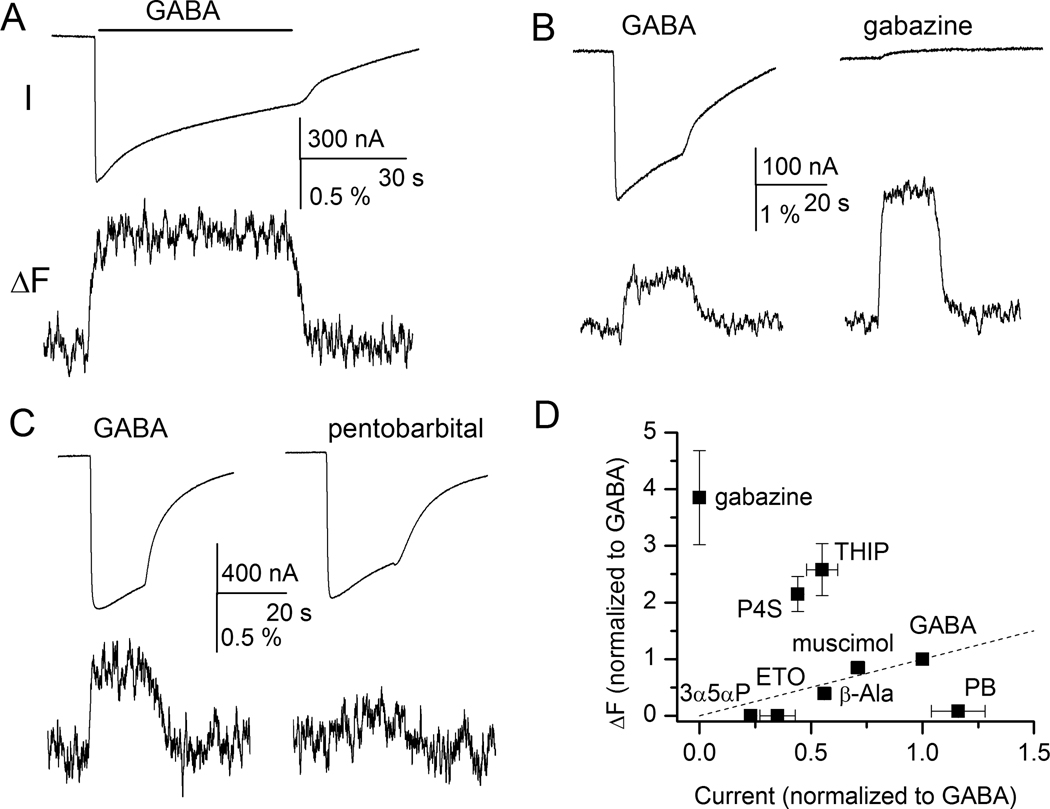

Figure 4.

Sample current and fluorescence recordings from the α1L127Cβ2γ2 receptor labeled with A5m. Receptors were expressed in Xenopus oocutes, and studied with two-electrode voltage clamp 30. (A) Exposure to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) elicits an inward current response (I) and an increase in fluorescence intensity (ΔF) suggesting that the environment around the fluorophore becomes more hydrophobic during channel activation. Channel desensitization does not affect fluorescence changes. (B) Exposure to the competitive antagonist gabazine does not activate the receptor but elicits fluorescence change (ΔF). For comparison, responses to GABA from the same cell are also shown. (C) Activation by GABA but not pentobarbital induces ΔF. Both sets of traces are from the same cell. (D) Relationship between current and fluorescence change. The responses are normalized to those to GABA. The normalized ΔF is plotted as a function of normalized current response. P4S = piperidine-4-sulfonic acid; THIP =4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol; 3α5αP = allopregnanolone; ETO = etomidate; β-Ala = β-alanine, PB = pentobarbital. Panels A, C, and D are reproduced with permission from Akk et al 30.

During prolonged agonist exposure the GABAA receptor desensitizes, which in current recordings manifests as reduced amplitude of the response. The data on the time courses of simultaneous fluorescence traces are scant. For the α1 subunit E122C and L127C sites (both in Loop E), two studies 30,33 found no evidence for a concurrent sag in the ΔF signal, indicating that the fluorescent reporters at the transmitter binding site are not sensing rearrangements associated with channel desensitization.

An increase in applied GABA concentration leads to an increase in the current response and the ΔF. In most cases, the concentration-response relationships are indistinguishable for the two, indicating that the conformational changes underlying the ΔF are associated with channel activity. Akk et al. 30 showed that the fitted EC50s for current and fluorescence responses from the α1L127Cβ2γ2 receptor labeled with A5m were within a factor of two from each other. In the ρ1 receptor, labeled with A5m at the Y241C (Loop C), L166C (Loop E), or S66C sites (subunit interface), the GABA-elicited current and ΔF curves are essentially superimposable 27. In contrast, the ρ1K217C residue has the ΔF concentration-response curve left-shifted by 6-fold compared to the activation curve 28. It was proposed that in the ρ1K217C receptor the structural rearrangements take place, and are observed as ΔF, under conditions where only one or two of the five agonist binding sites are occupied whereas currents can be observed following the binding of a minimum of three GABA molecules 28.

Higher ΔF signal at higher GABA concentrations indicates a correlation between the conformational changes underlying the fluorescence change and some aspect of channel activation, such as a higher fraction of occupied or active receptors. This implies that partial agonists and/or competitive antagonists should exhibit ΔF that is distinct from that for full agonists if the ligand-induced movements are translated to channel gating. However, the experimental support for this is scarce.

In the homooligomeric ρ1 receptor, Khatri et al. 28 found that receptors labelled at five different positions in Loop F showed no correlation between the ability of the ligand to elicit a ΔF and to activate the receptor. The partial agonists imidazole-4-acetic acid and isoguvacine exhibited a narrow range of ΔF from the various mutants, regardless of the level of activation. In the α1L127Cβ2γ2, Akk et al. 30 showed a lack of correlation between the peak current and magnitude of ΔF when the parameters for GABA were compared to those for the partial agonists piperidine-4-sulfonic acid (P4S) or 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol (THIP). The ΔF in the presence of P4S or THIP was significantly larger than in the presence of GABA. In contrast, β-alanine and muscimol elicited smaller currents and a smaller fluorescence change compared to GABA. Together, these data suggest that the ΔF readings in these examples report local structural changes associated with or following ligand binding rather than global structural changes associated with transduction of binding to movement of the gate.

Competitive inhibitors interact with the transmitter binding site but do not activate the receptor. Competitive antagonism can thus be considered as an extreme case of partial agonism. The ΔF observed in the presence of competitive inhibitors should reflect structural changes that are not associated with channel opening. Indeed, Muroi et al. 33 showed that α1β2γ2 receptors labeled at the α1L127C residue with tetramethylrhodamine maleimide (TMRM) exhibit an increase in fluorescence intensity when the receptor is activated by GABA, but a decrease in fluorescence when the receptor is exposed to the competitive inhibitor gabazine. This suggests that the two ligands produce different structural changes. It was proposed that in the presence of GABA, the GABA-binding cavity closes, shortening the distance between the neighboring α and β subunits, a process which may initiate the global rearrangements leading to channel gating. Exposure to gabazine, in this scenario, causes an opposite pattern of movement that does not lead to channel opening. In contrast, Akk et al. 30 found that when α1L127Cβ2γ2 receptors were labelled with A5m, GABA and gabazine elicited ΔF of the same sign (fig. 4B). The two fluorophores, TMRM and A5m, differ in their linker lengths (5Å for TMRM, 15 Å for A5m) meaning that the fluorophores bound to the same residue are positioned in different locations and report different changes in environment. It is unlikely that the structural rearrangements themselves differ in receptors labeled with different fluorophores.

In the α1β2γ2 receptor labeled with TMRM at the γ2S195C site (Loop F), Wang et al. 29 found a correlation between the ability of a ligand (GABA, β-alanine, gabazine) to induce currents and ΔF. Loop F of the γ subunit does not contribute to the transmitter binding site, indicating that the allosteric conformational change in Loop F of the γ subunit is associated with channel activation. Labeling of a Loop F residue in the α1 subunit (α1R186C) results in ΔF which is similar in magnitude and sign for GABA, β-alanine, and the antagonist gabazine 29. This suggests that the ΔF for Loop F of the α subunit reflects the binding event. Similarly, Loop F residues in the ρ1 receptor show similar ΔF in the presence of GABA, and the competitive inhibitors 3-aminopropylphosphonic acid or 3-aminopropyl-(methyl)phosphinic acid 28,35.

In ρ1 receptors labeled at the Y241C residue (Loop C), the competitive inhibitor 3-aminopropyl-(methyl)phosphinic acid, like GABA, leads to an increase in fluorescence although the magnitude of change is smaller than in the presence of the transmitter 27. However, when the receptors are labeled at the L166C (Loop E) or S66C residue, 3-aminopropyl-(methyl)phosphinic acid elicits ΔF that has an opposite sign to the ΔF in the presence of GABA. Exposure to the competitive antagonist 3-aminopropylphosphonic acid elicits a ΔF of the same sign as GABA when the receptors are labeled at the Y241C residue. In ρ1L166C receptors, the ΔF has an opposite direction to that of GABA, and no ΔF is observed at the S66C site. Overall, the data indicate that the classic competitive antagonists do not act solely to sterically prevent the binding of GABA, and that these drugs can induce structural changes of their own. A full summary of fluorescence changes observed during channel activation is given in table 1.

Movements during channel activation by allosteric ligands

The GABAA receptor can be directly activated by many neurosteroids, barbiturates, and general anesthetics such as etomidate and propofol. These drugs interact with sites which are distinct from the transmitter binding site. The binding site mediating direct activation by neurosteroids is located in the membrane-spanning region at the interface between α and β subunits where it is lined by the αT236 and βY284 residues (numbering from the rat α1 and β2 subunits; 16). Etomidate binds to a pocket in the membrane-spanning region at the interface between the α (α1M236) and β (β3M286) subunits 17. The barbiturate binding site is likely located within the membrane-spanning region 38,39 although the details are unknown at present.

Fluorescence studies have shown that channel activation by these allosteric activators does not typically elicit structural changes at the transmitter binding site. Muroi et al. 33 examined the current and fluorescence responses from the α1E122C and α1L127C sites (Loop E), and the homologous residues in the β2 subunit. Pentobarbital, at concentrations which elicit direct responses without significant channel block, did not induce changes in fluorescence intensity from TMRM-labelled receptors expressed in αβ or αβγ configuration. Work on A5m-labeled α1L127Cβ2γ2 receptors found that fluorescence was not affected during channel activation by saturating concentrations of pentobarbital, or etomidate or the neurosteroid allopregnanolone 30 (fig. 4C–D). Clearly, GABA and pentobarbital can activate the receptor without inducing similar structural changes near the transmitter binding site, but it should be noted that both allopregnanolone and etomidate are relatively ineffective activators of the α1L127Cβ2γ2 receptor and that the low activation status may have precluded the observation of the ΔF signal.

Fluorescence elicited from a residue near the top of M2 (24') in the β2 subunit, β2K274C, shows different responses to GABA and pentobarbital 37. In receptors constisting of α and β subunits, pentobarbital elicits an increase in fluorescence while GABA is without effect. In αβγ receptors, GABA elicits a negative ΔF, while low concentrations of pentobarbital are without effect. In sum, these findings indicate that GABA and pentobarbital activate the GABAA receptor by mechanisms involving different structural changes in the receptor. A summary of the fluorescence data is given in table 1.

Movements during modulation

Besides direct activation, allosteric ligands such as neurosteroids, barbiturates, etomidate and propofol potentiate GABAA receptor activity elicited by low concentrations of GABA 40–43. In addition, benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam), for which direct activation has not been found, can enhance GABAA receptor activity 44.

Several studies have investigated structural changes that take place during positive or negative modulation of the GABAA receptor. Wang et al. 29 found that a residue in Loop F in the γ2 subunit (γ2S195C) responded with a decrease in fluorescence when the receptor was activated by GABA, whereas fluorescence levels increased when the benzodiazepine diazepam was coapplied with GABA. A positive ΔF was also observed with the benzodiazepine inverse agonist, methyl-6,7-dimethoxy-4-ethyl-β-carboline-3-carboxylate, indicating that the two benzodiazepine site ligands induce local conformational changes associated with occupation of the benzodiazepine site. Diazepam also induces a conformational change in the M2–M3 linker region (N20'C) of the α subunit. Interestingly, the sign of ΔF depends on the presence of the γ subunit, suggesting that the occupation of the high-affinity benzodiazepine site in αβγ receptors leads to a structural rearrangement that is different from the change in αβ receptors containing only the low-affinity site45.

Akk et al. 30 examined the potentiating effect of a selected group of modulators on α1β2γ2 receptors labeled with A5m at the α1L127C site. In a simple allosteric model for receptor activation, an open state of the receptor is associated with increased affinity for agonist. This model predicts that a drug which increases channel activation at a given agonist concentration would also increase ΔF due to increased occupancy of the transmitter binding site. It was found that coapplication of etomidate or the neurosteroid allopregnanolone with a low concentration of GABA led to an increase in the the current response and an enhanced fluorescence change. In contrast, the presence of pentobarbital led to an enhanced current response without affecting ΔF. The findings on pentobarbital were confirmed by additionally examining potentiation of currents elicited by a partial agonist, P4S, and during coapplication of pentobarbital with gabazine. In the latter case, gabazine acts as a noncompetitive antagonist of channel opening by pentobarbital, reducing the peak current by stabilizing the inactive state of the receptor. This experiment allows to independently verify the interactions of both drugs with the receptor: the binding of pentobarbital is confirmed by the presence of the current response, and the binding of gabazine to the same population of receptors is confirmed by the reduction of the current amplitude. In the α1L127Cβ2γ2 receptor, gabazine elicits a fluorescence change while pentobarbital does not. The coapplication of pentobarbital with gabazine would be expected to shift the receptor population towards states with low affinity to the inhibitor reducing the number of receptors with gabazine bound, and hence reduce the ΔF from the receptor population. However, the gabazine-induced ΔF was not affected by pentobarbital. Thus, three separate experiments indicate that the application of pentobarbital does not affect ΔF at the α1L127C site. Overall, the results can be interpreted in the framework of a model where exposure to etomidate and allopregnanolone, but not pentobarbital, causes structural changes in the transmitter binding site that can be associated with increased affinity to the agonist 30.

A study comparing the effects of selected neurosteroids on the ρ1 receptor labeled at the Y241C (Loop C), L166C (Loop E), K217C (Loop F), or S66C (subunit-subunit interface) found that the steroids, in addition to reducing peak current, could in some cases reduce the magnitude of ΔF 21. The effects on fluorescence were specific to a combination of steroids and sites. For example, the application of sulfated steroids, e.g., pregnanolone sulfate or allopregnanolone sulfate reduced the ΔF from receptors labelled at the ρ1K217C site. In contrast, the application of pregnanolone, 5β-THDOC or 17β-estradiol was without effect on fluorescence. When the receptors were labeled at the L166C site, 17β-estradiol, but not pregnanolone, 5β-THDOC, pregnanolone sulfate or allopregnanolone sulfate, influenced the magnitude of ΔF. Application of the sulfated steroids and 17β-estradiol affected the fluorescence change produced at the ρ1S66C site. None of the steroids tested affected ΔF at the ρ1Y241 residue. Steroid-induced effects on conformational changes in the extracellular domain are generally not consistent with the steroids acting as classic open-channel blockers. It was concluded that the steroids act through an allosteric mechanism, however given the distinct conformational changes in the extracellular domain, different steroids can act through different molecular mechanisms 21.

Picrotoxin is a noncompetitive antagonist with its interaction site in the channel pore 46. Its mechanism of action is not solely pore block, rather it is allosteric and can be use-dependent 47. The application of picrotoxin alone elicits no ΔF from residues (α1E122C and α1L127C) near the transmitter binding site of the α1β2γ2 receptor 33. In the ρ1 receptor, coapplication of picrotoxin with GABA reduces the peak current but has little effect on the ΔF for A5m-labelled Y241C or L166C receptors. When the receptor is labelled at the S66C site the application of picrotoxin reduces, with similar IC50 values, the current and fluorescence responses 27. These findings indicate that picrotoxin-mediated antagonism is associated with long-distance structural changes, although the effect on the structure of the transmitter binding site may be limited given the lack of effect on ΔF produced at the Y241C and L166C sites. In Loop F, the presence of picrotoxin reduces ΔF from the K210C, K217C, T218C and I222C residues, but is without effect at fluorescence changes from K211C or L216C 35.

Summary of fluorescence studies and comparison with other structural studies

Voltage-clamp fluorometry can be a powerful tool in the studies of receptor dynamics. Some of the findings have been useful in confirming results from previous studies employing other techniques (e.g., the substituted cysteine accessibility method 48). Others have provided novel structural information, such as the effect of desensitization on structural rearrangements, that may be difficult to obtain with conventional approaches and techniques. A distinctive feature of voltage-clamp fluorometry is that the ΔF signal reports real-time environmental changes whereas the substituted cysteine accessibility method reports a functional effect due to the binding of the modifying agent. In this respect, both methods complement each other. We now provide a brief comparison of the salient results from fluorescence studies on GABAA receptors with studies involving the effects of MTS reagents on function.

Drugs considered to act through competitive antagonism can in some cases elicit fluorescence changes. Two aspects of this phenomenon should be considered. First, the very fact that a competitive antagonist is capable of eliciting ΔF suggests that the drug acts not solely by sterically interfering with agonist binding but rather can induce a structural change of its own. These findings and conclusion are in agreement with previous work in which the substituted cysteine accessibility method was employed. Boileau et al. 49 found that gabazine triggers a conformational rearrangement near the β2D95C (Loop A) residue. Gabazine also induces a structural change in Loop E in the α1 subunit 50. Second, in some cases the agonist (GABA) and competitive antagonist (gabazine) elicit ΔF that have opposite signs. This can be interpreted as the two classes of drugs inducing distinct structural changes: one type in the presence of an agonist, another in the presence of a competitive antagonist. A previous study found that GABA and gabazine differentially affect the chemical reactivity of MTS reagents with engineered cysteine residues in the transmitter binding site 50.

The comparison of the pattern of fluorescence signals indicates that GABA and the allosteric activator pentobarbital elicit non-identical structural changes. This agrees with results from studies employing the substituted cysteine accessibility method. In the transmitter binding site, MTS reactivity is similarly affected by GABA and pentobarbital at the α1E122C site, but differentially affected at the α1L127C site 50. In the pre-M1 region both GABA and pentobarbital induce structural changes. However, the nature of rearrangements is different. GABA affects the reaction rate for an MTS reagent with the β2K213C residue but is without effect on α1K221C. For pentobarbital the effect is opposite - pentobarbital affects the reaction rate at the α1K221C site but not β2K213C 51. The differences in structural changes may be lost near or at the channel gate. At the M2 6' level GABA and high, directly-activating concentrations of pentobarbital (as well as general anesthestics propofol and isoflurane) induce similar conformational changes as evidenced by disulfide trapping between engineered cysteines 52. The single-channel conductance is also indistinguishable for GABA and pentobarbital 53 indicating that the open channel structures are alike.

Studies on the ρ1 receptor found that inhibitory drugs can interfere with structural changes in the extracellular domain. However, the effects differ for different agents, which produce a pattern of effects falling into one of three distinct classes. These findings are supported by an earlier electrophysiologic study which proposed a similar classification of inhibitory agents based on their sensitivity to mutations in the membrane-spanning domain 54.

Future directions

Fluorescent reporters provide data complementary to functional data on channel activation, and enhance our ability to construct models for understanding drug action. We believe that this approach opens up a number of opportunities for novel insights into anesthetic actions.

One necessary, initial step is to continue to work to associate fluorescence signals with particular states of the receptor (e.g., bound, activated, desensitized or modulated), an area which is poorly explored at the present.

We have only examined a few anesthetics using this approach. Because many anesthetics appear to have similar actions to stabilize the open state of the GABAA receptor, additional information on structural consequences of anesthetic action have the promise to separate anesthetics based on mechanism as well as binding site, rather than functional effect.

A critical step is to examine the effects of anesthetic drugs on resting or transmitter-elicited fluorescence changes at additional sites in the receptor. Our present stable of sites is quite restricted, and must be expanded.

Overall, voltage-clamp fluorometry has strong potential to clarify the similarities and differences of the mechanisms of action for anesthetic compounds. At present, we are faced with the situation that anesthetics enhance GABAA receptor activation, but little understanding of the structural basis. Greater insight into the structural basis of potentiation will certainly enhance our understanding of anesthetic mechanisms, and has the potential to guide further explanation of drug structure-activity relations.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants R03ES17484 (to Dr. Akk) and P01GM47969 (to Dr. Steinbach) from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Maryland), and the Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri (to Dr. Akk and Dr. Steinbach).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonin RP, Orser BA. GABAA receptor subtypes underlying general anesthesia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franks NP. General anaesthesia: From molecular targets to neuronal pathways of sleep and arousal. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:370–386. doi: 10.1038/nrn2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones-Davis DM, Macdonald RL. GABAA receptor function and pharmacology in epilepsy and status epilepticus. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:12–18. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers CJ, Twyman RE, Macdonald RL. Benzodiazepine and β-carboline regulation of single GABAA receptor channels of mouse spinal neurones in culture. J Physiol. 1994;475:69–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akk G, Bracamontes JR, Covey DF, Evers A, Dao T, Steinbach JH. Neuroactive steroids have multiple actions to potentiate GABAA receptors. J Physiol. 2004;558:59–74. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.066571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen RW, Sieghart W. GABAA receptors: Subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tia S, Wang JF, Kotchabhakdi N, Vicini S. Distinct deactivation and desensitization kinetics of recombinant GABAA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1375–1382. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Picton AJ, Fisher JL. Effect of the α subunit subtype on the macroscopic kinetic properties of recombinant GABAA receptors. Brain Res. 2007;1165:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levitan ES, Blair LA, Dionne VE, Barnard EA. Biophysical and pharmacological properties of cloned GABAA receptor subunits expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Neuron. 1988;1:773–781. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gingrich KJ, Roberts WA, Kass RS. Dependence of the GABAA receptor gating kinetics on the α-subunit isoform: Implications for structure-function relations and synaptic transmission. J Physiol. 1995;489(Pt 2):529–543. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas KF, Macdonald RL. GABAA receptor subunit γ2 and δ subtypes confer unique kinetic properties on recombinant GABAA receptor currents in mouse fibroblasts. J Physiol. 1999;514(Pt 1):27–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.027af.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schofield PR, Darlison MG, Fujita N, Burt DR, Stephenson FA, Rodriguez H, Rhee LM, Ramachandran J, Reale V, Glencorse TA, Seeburg PH, Barnard EA. Sequence and functional expression of the GABAA receptor shows a ligand-gated receptor super-family. Nature. 1987;328:221–227. doi: 10.1038/328221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corringer PJ, Le Novere N, Changeux JP. Nicotinic receptors at the amino acid level. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:431–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sigel E, Buhr A. The benzodiazepine binding site of GABAA receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:425–429. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu M, Akabas MH. Identification of channel-lining residues in the M2 membrane-spanning segment of the GABAA receptor α1 subunit. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:195–205. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HM, Smart TG. Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature. 2006;444:486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature05324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li GD, Chiara DC, Sawyer GW, Husain SS, Olsen RW, Cohen JB. Identification of a GABAA receptor anesthetic binding site at subunit interfaces by photolabeling with an etomidate analog. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11599–11605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins A, Greenblatt EP, Faulkner HJ, Bertaccini E, Light A, Lin A, Andreasen A, Viner A, Trudell JR, Harrison NL. Evidence for a common binding cavity for three general anesthetics within the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kash TL, Trudell JR, Harrison NL. Structural elements involved in activation of the γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:540–546. doi: 10.1042/BST0320540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sine SM, Engel AG. Recent advances in Cys-loop receptor structure and function. Nature. 2006;440:448–455. doi: 10.1038/nature04708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li P, Khatri A, Bracamontes J, Weiss DS, Steinbach JH, Akk G. Site-specific fluorescence reveals distinct structural changes induced in the human ρ1 GABA receptor by inhibitory neurosteroids. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:539–546. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.062885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mannuzzu LM, Moronne MM, Isacoff EY. Direct physical measure of conformational rearrangement underlying potassium channel gating. Science. 1996;271:213–216. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mourot A, Bamberg E, Rettinger J. Agonist- and competitive antagonist-induced movement of loop 5 on the α subunit of the neuronal α4β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Neurochem. 2008;105:413–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahan DS, Dibas MI, Petersson EJ, Auyeung VC, Chanda B, Bezanilla F, Dougherty DA, Lester HA. A fluorophore attached to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor βM2 detects productive binding of agonist to the αδ site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10195–10200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0301885101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pless SA, Dibas MI, Lester HA, Lynch JW. Conformational variability of the glycine receptor M2 domain in response to activation by different agonists. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36057–36067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706468200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pless SA, Lynch JW. Ligand-specific conformational changes in the α1 glycine receptor ligand-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15847–15856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809343200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang Y, Weiss DS. Site-specific fluorescence reveals distinct structural changes with GABA receptor activation and antagonism. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1163–1168. doi: 10.1038/nn926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khatri A, Sedelnikova A, Weiss DS. Structural rearrangements in loop F of the GABA receptor signal ligand binding, not channel activation. Biophys J. 2009;96:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, Pless SA, Lynch JW. Ligand- and subunit-specific conformational changes in the ligand-binding domain and the TM2–TM3 linker of α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors. J Biol Chem. 285:40373–40386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.161513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akk G, Li P, Bracamontes J, Wang M, Steinbach JH. Pharmacology of structural changes at the GABAA receptor transmitter binding site. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:840–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts DD, Lewis SD, Ballou DP, Olson ST, Shafer JA. Reactivity of small thiolate anions and cysteine-25 in papain toward methyl methanethiosulfonate. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5595–5601. doi: 10.1021/bi00367a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stauffer DA, Karlin A. Electrostatic potential of the acetylcholine binding sites in the nicotinic receptor probed by reactions of binding-site cysteines with charged methanethiosulfonates. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6840–6849. doi: 10.1021/bi00188a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muroi Y, Czajkowski C, Jackson MB. Local and global ligand-induced changes in the structure of the GABAA receptor. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7013–7022. doi: 10.1021/bi060222v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlin A. Chemical modification of the active site of the acetylcholine receptor. J Gen Physiol. 1969;54:245–264. doi: 10.1085/jgp.54.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, Xue F, Chang Y. Agonist- and antagonist-induced conformational changes of loop F and their contributions to the ρ1 GABA receptor function. J Physiol. 2009;587:139–153. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charnet P, Labarca C, Leonard RJ, Vogelaar NJ, Czyzyk L, Gouin A, Davidson N, Lester HA. An open-channel blocker interacts with adjacent turns of α-helices in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neuron. 1990;4:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90445-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muroi Y, Theusch CM, Czajkowski C, Jackson MB. Distinct structural changes in the GABAA receptor elicited by pentobarbital and GABA. Biophys J. 2009;96:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amin J. A single hydrophobic residue confers barbiturate sensitivity to γ-aminobutyric acid type C receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:411–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serafini R, Bracamontes J, Steinbach JH. Structural domains of the human GABAA receptor β3 subunit involved in the actions of pentobarbital. J Physiol. 2000;524(Pt 3):649–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akk G, Covey DF, Evers AS, Mennerick S, Zorumski CF, Steinbach JH. Kinetic and structural determinants for GABAA receptor potentiation by neuroactive steroids. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:18–25. doi: 10.2174/157015910790909458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akaike N, Tokutomi N, Ikemoto Y. Augmentation of GABA-induced current in frog sensory neurons by pentobarbital. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:C452–C460. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.3.C452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hales TG, Lambert JJ. The actions of propofol on inhibitory amino acid receptors of bovine adrenomedullary chromaffin cells and rodent central neurones. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;104:619–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forman SA. Clinical and molecular pharmacology of etomidate. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:695–707. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ff72b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bianchi MT. Context dependent benzodiazepine modulation of GABAA receptor opening frequency. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:10–17. doi: 10.2174/157015910790909467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walters RJ, Hadley SH, Morris KD, Amin J. Benzodiazepines act on GABAA receptors via two distinct and separable mechanisms. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1274–1281. doi: 10.1038/81800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu M, Covey DF, Akabas MH. Interaction of picrotoxin with GABAA receptor channel-lining residues probed in cysteine mutants. Biophys J. 1995;69:1858–1867. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoon KW, Covey DF, Rothman SM. Multiple mechanisms of picrotoxin block of GABA-induced currents in rat hippocampal neurons. J Physiol. 1993;464:423–439. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karlin A, Akabas MH. Substituted-cysteine accessibility method. Methods Enzymol. 1998;293:123–145. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)93011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boileau AJ, Newell JG, Czajkowski C. GABAA receptor β2 Tyr97 and Leu99 line the GABA-binding site. Insights into mechanisms of agonist and antagonist actions. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2931–2937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kloda JH, Czajkowski C. Agonist-, antagonist-, and benzodiazepine-induced structural changes in the α1 Met113-Leu132 region of the GABAA receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:483–493. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mercado J, Czajkowski C. γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and pentobarbital induce different conformational rearrangements in the GABA A receptor α1 and β2 pre-M1 regions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15250–15257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708638200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosen A, Bali M, Horenstein J, Akabas MH. Channel opening by anesthetics and GABA induces similar changes in the GABAA receptor M2 segment. Biophys J. 2007;92:3130–3139. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.094490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akk G, Steinbach JH. Activation and block of recombinant GABAA receptors by pentobarbitone: A single-channel study. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:249–258. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li W, Jin X, Covey DF, Steinbach JHDF, Steinbach JH. Neuroactive steroids and human recombinant ρ1 GABAC receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:236–247. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]