Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus infections continue to pose a global public health problem. Frequently, this epidemic is driven by the successful spread of single S. aureus clones within a geographic region, but international travel has been recognized as a potential risk factor for S. aureus infections. To study the molecular epidemiology of S. aureus infections in the Caribbean, a major international tourist destination, we collected methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolates from community-onset infections in the Dominican Republic (n=112) and Martinique (n=143). Isolates were characterized by a combination of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), spa typing, and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) typing. In Martinique, MRSA infections (n=56) were mainly caused by t304-ST8 strains (n=44), whereas MSSA isolates were derived from genetically diverse backgrounds. Among MRSA strains (n=22) from the Dominican Republic, ST5, ST30, and ST72 predominated, while ST30 t665-PVL+ (30/90) accounted for a substantial number of MSSA infections. Despite epidemiological differences in sample collections from both countries, a considerable number of MSSA infections (~10%) were caused by ST5 and ST398 isolates at each site. Further phylogenetic analysis suggests the presence of lineages shared by the two countries, followed by recent genetic diversification unique to each site. Our findings also imply the frequent import and exchange of international S. aureus strains in the Caribbean.

Introduction

The emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) is causing a worldwide public health problem. A limited variety of genetically distinct S. aureus strains is driving this epidemic in different geographic locations, such as ST8 (USA300) in the United States [1], ST80 in some European countries [2–4], or ST75 in remote indigenous Australian communities [5]. Subsequent global spreading of these clones has been detected, such as USA300 into Australia [6], Europe [7, 8], or Japan [9]. However, the pandemic spread of S. aureus is not limited to the presence of methicillin resistance: methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) phage 80/81 was the first to sweep from hospitals in Australia to Europe, Africa, and the Americas in the 1950s [10]. A more recent example of a very successful MSSA includes ST121, which has been encountered in several European countries and parts of Russia [11–13]

Increasingly, it has been noted that returning international travelers with MRSA infections contracted strains specific to their country of vacation [14, 15]. However, it remains unclear as to what extent frequent travel and migration between regions influences the local epidemiology of S. aureus infections. We recently obtained evidence for a possible “air-bridge link” for the exchange of ST398 MSSA between the predominantly Dominican population of Northern Manhattan and the Dominican Republic (DR) [16]. This prompted further interest into the molecular epidemiology of S. aureus infections in the Caribbean, a major destination of international travel and source of agricultural export [17]. There are substantial differences in the country of origin and frequency of travelers arriving between Caribbean islands. The DR is one of the most frequently visited countries in this region, with ~4 million tourists arriving per year, including about 40% Europeans (from Germany, Italy, and the UK), 33% American, and 17% Canadian visitors, and an additional ~580,000 Dominicans returning from living overseas. In contrast, the French overseas department Martinique is the destination of ~500,000 visitors each year, with the majority (75%) arriving from France and only 3.6% from North America [17].

We, therefore, aimed to characterize S. aureus isolates from the DR, located in the Northern Caribbean and linked by travel to both North America and Europe, and contrast this with S. aureus from the South-Eastern Caribbean island Martinique, which, by air travel, is primarily connected to France. We hypothesized that these two countries with differing travel links would have a substantially distinct molecular epidemiology of S. aureus infections.

Materials and methods

Sample selection

We obtained a convenience sample of 112 clinical S. aureus isolates processed by the Referencia laboratory in Santo Domingo, DR, between February 2007 and July 2008. These strains were collected from outpatients who presented to clinics in Santo Domingo (n=98) or across the country (n=14), and basic demographic information was provided (Table 1). The majority of infections (n=86, 77%) were skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), while the remainder (n=26) included conjunctivitis, otitis, and urinary tract infections.

Table 1.

Distribution of selected demographic and clinical variables between the Dominican Republic and Martinique

| Dominican Republic n=112 |

Martinique n=94* |

p-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 25 (1–78) | 52 (0–98) | <.0001 |

| Gender, male (%) | 54 (48%) | 57 (61%) | 0.07 |

| Site of infection | |||

| Skin and soft tissue | 86 (77%) | 55 (58%) | <0.05 |

| Invasive infections | 0 (0%) | 17 (18%) | <0.001 |

| MRSA | 22 (20%) | 56 (39%) | <0.001 |

Clinical data on 94 out of 142 patients available

Using the Chi-square test for the comparison of dichotomous variables and independent samples t-test for the comparison of the age variable

In Martinique, we collected a convenience sample of 143 positive S. aureus isolates between August 2007 and April 2008 from outpatients presenting to Fort-de-France hospital in Fort-de-France, Martinique (Table 1). Demographic information was available for 94 of these samples. The majority of specimens were derived from SSTIs (n=55, 59%) and the remainder was collected from bloodstream infections (n=17, 18%), pneumonias (n=9, 9.6%), or urinary infections (n=10, 11.1%) or unspecified sites (n=3).

In both sites, none of these samples were obtained from international tourists, or were specifically collected during a local outbreak of S. aureus infections.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

All S. aureus isolates were tested for their susceptibilities to penicillin, cefoxitin, oxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, levofloxacin, gentamicin, vancomycin, clindamycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, and rifampin, using the Kirby–Bauer standard disk diffusion method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [18].

Molecular genotyping

All isolates were characterized by S. aureus protein A (spa) typing as described previously [19] and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). spa polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were sequenced and spa types automatically assigned using Ridom StaphType software (version 1.5) and compared to http://spaserver2.ridom.de. Using the integrated BURP (Based Upon Repeat Patterns) algorithm, spa types were clustered into spa clonal complexes (spa-CC) if the cost distances were <4 [20, 21]. spa types with<5 repeats were excluded, as they cannot be reliably clustered [21]. For visualization, phylogenetic trees were constructed using SplitsTree software (version 4.0) [22].

PFGE was carried out on SmaI or Clf91 digested samples [16, 23]. The resulting band patterns were analyzed by Bionumerics software (version 4.0, Applied Maths, Ghent, Belgium) to determine the relatedness between strains [24]. Profiles with >80% similarity were considered to be closely related. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed on at least one isolate of each spa-CC that also shared indistinguishable PFGE patterns as previously described [25]. Sequence types (STs) were assigned using http://saureus.mlst.net/.

Further screening for the presence of Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) [26] and for the type of staphylococcal chromosomal cassette (SCC)mec for MRSA isolates was performed by PCR as previously described [27].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18 software. Chi-square tests were used for the comparison of dichotomous variables, and Fisher’s exact test with an expected cell count of <5 and independent samples t-tests to compare age. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Dominican Republic

Most of the S. aureus isolates from the DR were MSSA (90/112; 80%). Of these MSSA strains, 81/90 (90%) were resistant to penicillin, 11/90 (12%) to erythromycin, and 6/90 (7%) to tetracycline, but less than 1% of isolates were resistant to levofloxacin, gentamicin, or clindamycin. The majority of the 22 MRSA isolates harbored SCCmec IV (18/22, 80%), except for four strains with SCCmec V. Five of the 22 MRSA isolates were resistant to≥4 antibiotics, whereas the remainder were only resistant to semi-synthetic penicillins or one additional class of drug.

Among the 112 isolates, 39 different spa types were detected, which clustered into ten distinct spa-CC by BURP analysis. One spa type was excluded (length<4 repeats) and 16 were classified as singletons (Figs. 1 and 2). Nine of the 39 different spa types had not been previously reported (t6018, t6019, t6711, t6721, t6723, t6724, t6725, t6726, and t6839).

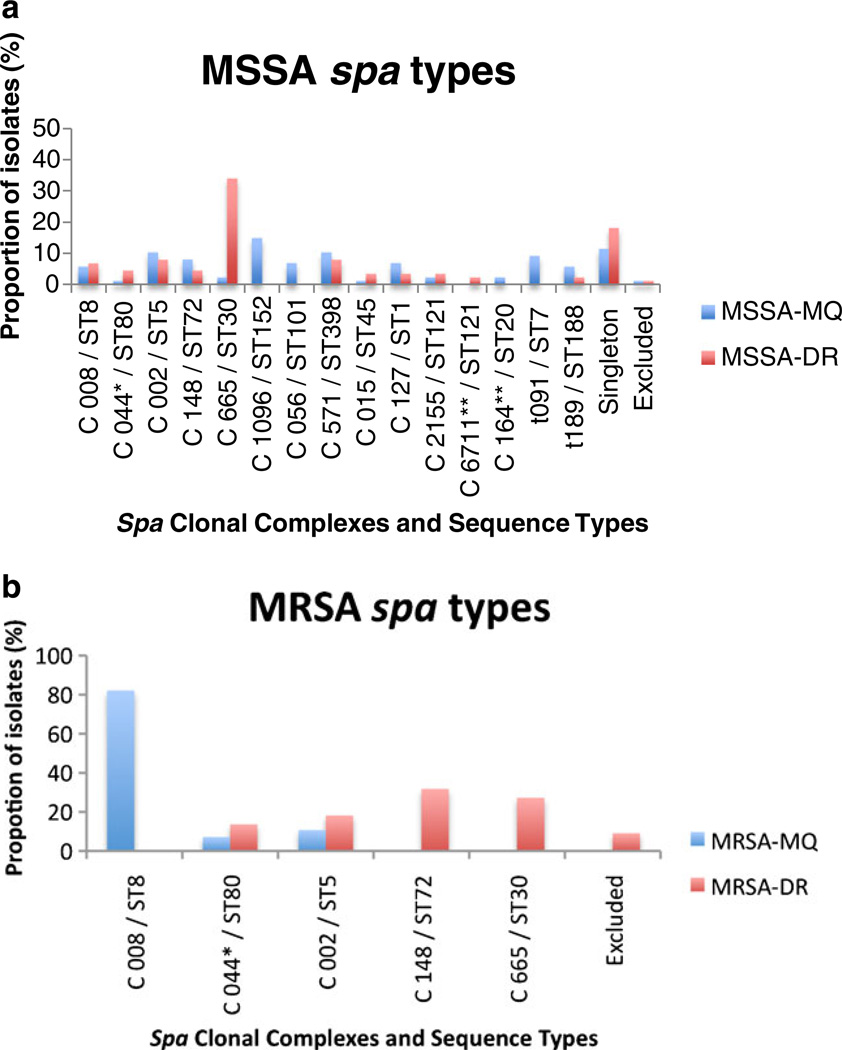

Fig. 1.

Observed frequency of spa clonal complexes/multilocus sequence typing (MLST) for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) (a) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (b) strains by geographic region (blue=Martinique, red=Dominican Republic). E=excluded from cluster analysis for short spa length. S=singleton (no cluster assigned or number <3). *More than one spa type as founder; **unknown founder

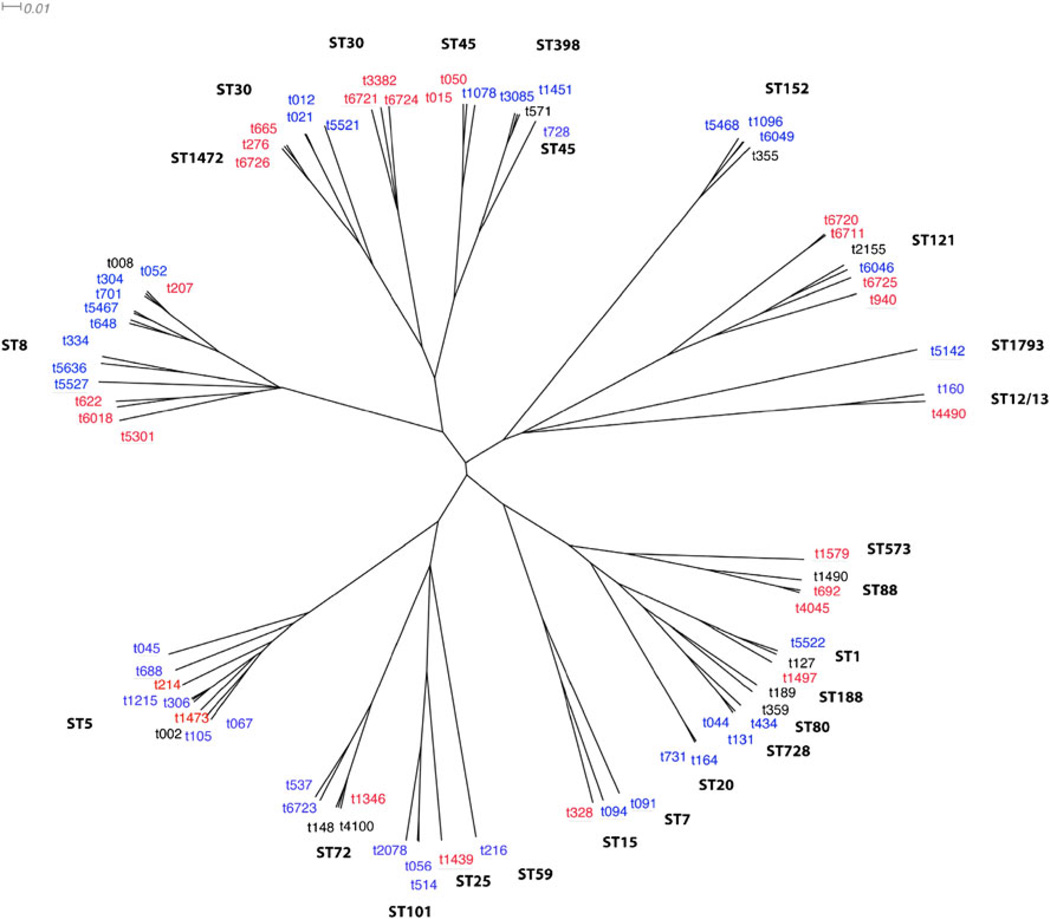

Fig. 2.

Neighbor-joining tree based on the distance matrix produced by BURP (Based Upon Repeat Patterns) software. All observed spa types by country of origin are as follows: blue=Martinique, red= Dominican Republic, black=present in both countries. Underlined spa types were not clustered in a BURP clonal complex (singleton). The indicated MLST clonal complex corresponds to all spa types in a given branch, unless otherwise indicated

The predominant spa type among the MSSA isolates from the DR was t665 (n=25, 28%). These strains were further defined as ST30 by MLST typing. Using BURP cluster analysis, spa-CC665/ST30 was the predominant CC and accounted for one-third of isolates (30/90, 33%; Fig. 1). spa-CC002 (ST5) and t571 (ST398) each accounted for seven samples (7.8%). Notably, we only detected 3/90 (3.3%) t008 USA300 MSSA strains in this sample collection, while spa-CC008 (ST8) accounted for 6/90 (6.6%) isolates (Fig. 1).

Among the MRSA isolates from the DR, spa-CC665/ST30 was again the predominant CC (6/22, 27%), followed by spa-CC148/ST72 (5/22, 23%) and spa-CC002/ST5, (4/22, 18%) (Fig. 2). None of the MRSA samples in this study was USA300 or ST8.

Further genotyping revealed that about half of the MSSA (41/90, 46%) and MRSA (10/22, 45%) strains were PVL-positive. The majority of these PVL-positive isolates belonged to spa-CC665/ST30 (31/51, 61%).

Martinique

Of the 143 Martinique S. aureus samples, 87 were MSSA and 56 were MRSA. About one-third of MSSA strains remained sensitive to penicillin, while only a small proportion of strains were resistant to erythromycin (13/87) or tetracycline (5/87). The majority ofMRSA strains harbored resistance to multiple drugs, including erythromycin (31/56) and levofloxacin (46/56), while sensitivity to tetracyclines was mainly preserved (2/56).

We identified eight new spa types in Martinique (t5467, t5468, t5521, t5522, t5526, t5527, t6046, and t6049), and one novel MLST type (ST1793). MSSA infections were caused by a genetically heterogeneous group of strains (Fig. 1). The two predominant clusters, spa-CC1096/ST152 (13/88, 15%) and spa-CC571 (9/88, 10%), together accounted for 25% of samples (Fig. 1).

All strains in the spa-CC571 cluster were confirmed as ST398 by MLST and shared profiles (>80% identical) by PFGE, irrespective of their country of isolation or spa type (not shown). This included t571, which we also encountered as the predominant ST398 spa type in both Northern Manhattan [16] and in the DR, as well as t1451 and t3085.

Martinique MRSA isolates clustered into ST80, ST5, and spa-CC008/ST8, which caused the majority of MRSA infections (44/55, 80%; Fig. 2). Seven of these spa-CC008 samples were t008 and USA300 by PFGE (not shown), but spa type t304 (27/55, 49%) was the predominant clone and differed substantially from USA300 by PFGE (~65% similarity). All t304 samples were SCCmec type IVc, PVL-negative, and ST8. Overall, only 5 of the 56 MRSA strains and 9 of the 87 MSSA strains were PVL-positive.

Combined assessment of S. aureus isolates from the DR and Martinique

While we attempted to obtain comparable collections of outpatient S. aureus isolates from both Caribbean countries, isolates from Martinique were derived from an older population (Table 1). In addition, Martinique patients more frequently had invasive infections (Table 1), with greater resistance to multiple antibiotics, indicating that, at least in part, samples may have been healthcare-associated. Despite these epidemiological differences, ST5 and ST80 were shared MRSA clones between the two countries, though the majority of infections were caused by ST8 in Martinique and ST30 and ST72 in the DR (Fig. 1b). When comparing the frequency of MSSA clones between the two Caribbean countries, the highly prevalent ST30 in the DR was only infrequently encountered in Martinique (Fig. 1a). The two most commonly shared CC present in both countries were spa-CC002/ST5 and spa-CC571/ST398 (Fig. 1).

Across the two islands, we identified 68 distinct and 11 shared spa types between Martinique and the DR (Fig. 2). To further elucidate the genetic relatedness of these strains, we generated a neighbor-joining tree based on the distance matrix produced by the BURP algorithm (Fig. 2). This phylogenetic tree illustrates that, while there was a high diversity in the presence of individual spa types between Martinique and the DR, usually at least one spa type per CC was shared, except for ST7, ST20, and ST152. This may suggest local diversification of a very similar pool of common strain ancestors.

Discussion

There is limited information on the molecular epidemiology of S. aureus infections in the Caribbean, a major destination of international tourism. Here, we report the presence of S. aureus clones in the DR and Martinique that previously had only been observed elsewhere. In addition, the presence of a substantial number of new spa types in both regions suggests recent local diversification of strains not otherwise encountered in other geographic areas. Furthermore, both Caribbean countries frequently shared MSSA genotypes, in particular, ST5 and ST398, but showed major differences between MRSA clones, which, in part, may be explained by disparities in the clinical sample collections tested.

Dominican MSSA and MRSA strains harbored STs commonly encountered in other parts of the world, such as ST80, in the Mediterranean, Balkan, Middle East, and Europe; ST30, in the Pacific, East Asia, and Oceania; and ST72 [2, 28, 29]. The latter strain causes CA-MRSA infections in South Korea and was also detected among immigrants from South Korea to Europe. However, the predominant South Korean spa types (t664, t324) differed from our ST72 spa types [29, 30]. This may still be consistent with the transmission of strains between regions, or, alternatively, could be explained by the much earlier dissemination of common ancestors and subsequent diversification of clones. In support of this diversification hypothesis is our observation that the presence of individual STs and spa-CC did not differ substantially between the two Caribbean countries (Fig. 2). This observation even applied to more uncommon STs, such as ST1472, which differs from ST30 in one base pair in the yqiL gene and was present as a new spa type in both Martinique (t6726) and the DR (t5521).

The high prevalence of ST30-PVL+ among Dominican MSSA and MRSA strains is consistent with recent reports indicating their global spread, including to the United States and Europe [23, 27, 28]. Interestingly, the first recognized pandemic S. aureus clone, phage 80/81 [10], also belongs to ST30. The remarkably widespread occurrence of ST30 suggests unique features in its core genome that potentially facilitate their transmission. However, the predominance of spa type t665 among Dominican ST30 MSSA and MRSA isolates suggests the emergence of MRSA from a locally successful MSSA t665/ST30 strain.

Only a very small proportion of the Martinique MSSA and none of the MRSA isolates belonged to ST30. The vast majority of MRSA from Martinique were spa t304, which is closely related to t008, the prototype of epidemic ST8/USA300 in the United States. These t304 strains differed substantially from USA300 by PFGE and none were PVL-toxin-positive, but they all belonged to ST8 and carried the SCCmec type IVc cassette. This specific spa type has infrequently been described as CA-MRSA in South Korea and in parts of Europe [30]. spa-t304 was only rarely detected among MSSA isolates and suggests that MRSA t304/ST8 evolved independently of a successful MSSA counterpart. Alternatively, this could also be consistent with a local outbreak of t304 MRSA strains.

In contrast to the DR, a substantial number of MSSA infections in Martinique were due to ST152, which has been associated with colonization in Mali and infections in Nigeria [31, 32]. However, in both Caribbean countries, ST398 MSSA accounted for a substantial number of infections (~10%). ST398 has been linked to MRSA outbreaks among Dutch pig farmers, though transmission beyond the immediate animal contacts or their families appears rare [33]. While we cannot exclude animal contact of infected patients in our sample, it is notable that the Dominican and Martinique ST398 isolates were collected at two urban medical centers (population of ~2 million in Santo Domingo and ~90,000 in Fort-de-Frances). This adds to our earlier observation in Northern Manhattan, where ST398 MSSA was detected in individuals without direct animal exposure [16].

spa-t571 was the most frequently encountered ST398 type in our samples from New York [16], the DR, and Martinique, and was also attributed in a case of fatal necrotizing pneumonia in France [34]. Both additional ST398 spa types from Martinique, namely, t3085 and t1451, have almost exclusively been detected in France. This raises the possibility that ST398 strains have either been imported from France into Martinique or vice versa. Detailed sequence comparisons may aid in gaining further understanding into the origin and dissemination of these strains.

There are several limitations to our study. First, samples are mainly representative of single centers in both countries, with the exception of some isolates (14%) collected across the DR. Second, while we aimed to obtain a representative snapshot of community-associated S. aureus infections in both sites, we were only able to collect a convenience sample with limited clinical or epidemiological information, such as co-morbidities, or recent hospitalizations or travel of patients. In particular, the higher age of patients from Martinique, the relatively high numbers of invasive isolates, and fluoroquinolone resistance suggests that a number of infections were related to healthcare exposure. Third, while the samples were not collected during known outbreaks of S. aureus infections at the study sites, we cannot fully exclude the possibility of clusters of infections accounting for some of the predominant clones. Fourth, we only obtained samples from one time period and were, therefore, unable to study changes in predominant strain patterns over time. Nevertheless, the results provide a profile of strain diversity in this previously unexamined geographic region.

It has been suggested that MSSA are less restricted to a particular geographic region than MRSA strains [35]. However, in the current study, we primarily observed the presence of a diversity of the international strains ST8, ST30, ST80, and ST72 in MRSA samples from the Caribbean. In light of reports of travelers returning to their home countries with S. aureus skin infections endemic to their travel destination [14], a tourist region visited by a diversity of travelers may also serve as a melting pot for MSSA and MRSA exchange and transmission.

Further prospective studies are warranted in order to more specifically study the molecular epidemiology of MSSA and MRSA infections in relation to “air-bridges” between countries with frequent travel or migration, such as in the Caribbean.

Acknowledgments

Transparency declaration This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 AI077690-0251). A.-C.U. received grant support from the NIH (K08 AI090013-01) and Columbia University Lucille P. Markey and Paul A. Marks scholarships. C.D. was supported by a Fulbright Scholar grant made possible by the U. S. Department of State, by the Franco-American Commission for Educational Exchange, and by a grant from the Bourse Collery de l’Académie Nationale de Médecine.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

A.-C. Uhlemann, Email: au2110@columbia.edu, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Columbia University Medical Center, 630W 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA.

C. Dumortier, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Columbia University Medical Center, 630W 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA

C. Hafer, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Columbia University Medical Center, 630W 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA

B. S. Taylor, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Columbia University Medical Center, 630W 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA.

J. Sánchez E, Referencia Laboratorio Clinico, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

C. Rodriguez-Taveras, Hospital Central de Las Fuerzas Armadas, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

P. Leon, Referencia Laboratorio Clinico, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

R. Rojas, Centro Medico Luperon, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

C. Olive, Centre Hospitalier Régional et Universitaire de Fort-de-France, Fort-de-France, France

F. D. Lowy, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Columbia University Medical Center, 630W 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA

References

- 1.Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:666–674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandenesch F, Naimi T, Enright MC, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton–Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:978–984. doi: 10.3201/eid0908.030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otter JA, French GL. Molecular epidemiology of community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:227–239. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faria NA, Oliveira DC, Westh H, et al. Epidemiology of emerging methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Denmark: a nationwide study in a country with low prevalence of mrsa infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1836–1842. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1836-1842.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimmo GR, Coombs GW. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Australia. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31:401–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottlieb T, Su WY, Merlino J, et al. Recognition of USA300 isolates of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Australia. Med J Aust. 2008;189:179–180. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruppitsch W, Stoger A, Schmid D, et al. Occurrence of the USA300 community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus clone in Austria. Euro Surveill. 2007;12 doi: 10.2807/esw.12.43.03294-en. E071025.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valentini P, Parisi G, Monaco M, et al. An uncommon presentation for a severe invasive infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone USA300 in Italy: a case report. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2008;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibuya Y, Hara M, Higuchi W, et al. Emergence of the community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 clone in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2008;14:439–441. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0640-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rountree PM, Beard MA. Further observations on infection with phage type 80 staphylococci in Australia. Med J Aust. 1958;45:789–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baranovich T, Zaraket H, Shabana II, et al. Molecular characterization and susceptibility of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolates from hospitals and the community in Vladivostok, Russia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:575–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasigade JP, Laurent F, Lina G, et al. Global distribution and evolution of Panton–Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, 1981–2007. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1589–1597. doi: 10.1086/652008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conceição T, Aires-de-Sousa M, Pona N, et al. High prevalence of ST121 in community-associated methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus lineages responsible for skin and soft tissue infections in Portuguese children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:293–297. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stenhem M, Ortqvist A, Ringberg H, et al. Imported methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:189–196. doi: 10.3201/eid1602.081655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helgason KO, Jones ME, Edwards G. Panton–Valentine leukocidin-positive Staphylococcus aureus and foreign travel. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:832–833. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02154-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhat M, Dumortier C, Taylor BS, et al. Staphylococcus aureus ST398, New York City and Dominican Republic. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:285–287. doi: 10.3201/eid1502.080609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latest tourism statistics. OneCaribbean. 2010. 2003–2010 http://www.onecaribbean.org/statistics/tourismstats/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Approved standard, 9th edn, CLSI document M2-A9. Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2006. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harmsen D, Claus H, Witte W, et al. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5442–5448. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5442-5448.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellmann A, Weniger T, Berssenbrügge C, et al. Characterization of clonal relatedness among the natural population of Staphylococcus aureus strains by using spa sequence typing and the BURP (based upon repeat patterns) algorithm. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2805–2808. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00071-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellmann A, Weniger T, Berssenbrügge C, et al. Based Upon Repeat Pattern (BURP): an algorithm to characterize the long-term evolution of Staphylococcus aureus populations based on spa polymorphisms. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huson DH. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:68–73. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung M, de Lencastre H, Matthews P, et al. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: comparison of results obtained in a multilaboratory effort using identical protocols and MRSA strains. Microb Drug Resist. 2000;6:189–198. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2000.6.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enright MC, Day NP, Davies CE, et al. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1008–1015. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1008-1015.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaneko J, Muramoto K, Kamio Y. Gene of LukF-PV-like component of Panton–Valentine leukocidin in Staphylococcus aureus P83 is linked with lukM. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:541–544. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milheiriço C, Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. Update to the multiplex PCR strategy for assignment of mec element types in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3374–3377. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00275-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tristan A, Bes M, Meugnier H, et al. Global distribution of Panton–Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, 2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:594–600. doi: 10.3201/eid1304.061316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bae IG, Kim JS, Kim S, et al. Genetic correlation of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from carriers and from patients with clinical infection in one region of Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:197–202. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsen AR, Stegger M, Böcher S, et al. Emergence and characterization of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphyloccocus aureus infections in Denmark, 1999 to 2006. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:73–76. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01557-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruimy R, Maiga A, Armand-Lefevre L, et al. The carriage population of Staphylococcus aureus from Mali is composed of a combination of pandemic clones and the divergent Panton–Valentine leukocidin-positive genotype ST152. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:3962–3968. doi: 10.1128/JB.01947-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breurec S, Zriouil SB, Fall C, et al. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages in five major African towns: emergence and spread of atypical clones. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:160–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cuny C, Nathaus R, Layer F, et al. Nasal colonization of humans with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) CC398 with and without exposure to pigs. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasigade JP, Laurent F, Hubert P, et al. Lethal necrotizing pneumonia caused by an ST398 Staphylococcus aureus strain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1330. doi: 10.3201/eid1608.100317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grundmann H, Aanensen DM, van den Wijngaard CC, et al. Geographic distribution of Staphylococcus aureus causing invasive infections in Europe: a molecular-epidemiological analysis. PLoS Med. 2010;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000215. e1000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]