Abstract

Polycaprolactone fumarate (PCLF) is a cross-linkable derivate of polycaprolactone diol that has been shown to be an effective nerve conduit material that supports regeneration across segmental nerve defects and has warranted future clinical trials. Degradation of the previously studied PCLF (PCLFDEG) releases toxic small molecules of diethylene glycol used as the initiator for the synthesis of polycaprolactone diol. In an effort to eliminate this toxic degradation product we present a strategy for the synthesis of PCLF from either propylene glycol (PCLFPPD) or glycerol (PCLFGLY). PCLFPPD is linear and resembles the previously studied PCLFDEG, while PCLFGLY is branched and exhibits dramatically different material properties. The synthesis and characterization of their thermal, rheological, and mechanical properties are reported. The results show that the linear PCLFPPD has material properties similar to the previously studied PCLFDEG. The branched PCLFGLY exhibits dramatically lower crystalline properties resulting in lower rheological and mechanical moduli, and is therefore a more compliant material. In addition, the question of an appropriate FDA approvable sterilization method is addressed. This study shows that autoclave sterilization on PCLF materials is an acceptable sterilization method for cross-linked PCLF and has minimal effect on the PCLF thermal and mechanical properties.

Keywords: Polycaprolactone fumarate, polyester, sterilization, nerve regeneration

1. Introduction

Polycaprolactone fumarate (PCLF) (chemical structure shown in Figure 1a) is a cross-linkable derivative of polycaprolactone that has been shown to be promising material for tissue engineering applications involving both the repair of segmental nerve defects as well as a bone substitute(1–3). PCLF has also been used as one component in a wide array of blends for biomaterial scaffolds from injectable in situ cross-linkable scaffolds(4–12), to drug delivery vehicles(13), to electrically conductive nerve conduits composed of PCLF and polypyrrole(14, 15). Previously, PCLF has been synthesized by condensation polymerization of fumaryl chloride with commercially available polycaprolactone diol of molecular weights 530, 1200, or 2000 g mol−1 (16). The mechanical, thermal, and rheological properties are controlled by the design of the PCLF polymer. For instance the tensile modulus can vary from 0.87 MPa to 138 MPa depending only on the molecular weight of the PCL precursor chosen(17).This range of mechanical properties allows PCLF to be used in both nerve and bone regeneration applications.

Figure 1.

a) Chemical structure of polycaprolactone fumarate (PCLF). b) 1H NMR of PCLDEG clearly showing the peak at 4.25 ppm corresponding to esterified diethylene glycol. c) Degradation products of PCLFDEG showing no peak at 4.25 ppm associated with the esterified diethylene glycol, and appearance of peaks at 3.65 and 3.75 associated with free diethylene glycol.

An ideal nerve conduit should possess several key characteristics including resistance to compression or collapse, suturability, flexibility, and a degradation rate that allows for complete regeneration before loss of the lumen integrity(18, 19). Previous work has shown that PCLF synthesized from PCL diol with Mn of 2000 g mol−1 has the most favorable material properties over other PCLF formulations synthesized from PCL 530 or 1250 for satisfying the above mentioned criteria. Therefore PCLF synthesized from PCL2000 has been used extensively for the production of nerve conduits to repair segmental nerve defects. PCLF nerve conduits have been shown to support robust nerve regeneration across the 1 cm rat sciatic nerve defect model(2) and have warranted future clinical studies.

In preparation for upcoming clinical trials the potential degradation products released from the PCLF scaffolds were analyzed. During the course of this degradation study, it was determined by 1H NMR that diethylene glycol can be released during hydrolysis as one degradation product from the previously studied PCLF (PCLFDEG) (1 H NMR of PCLDEG and PCLFDEG degradation products are shown in Figures 1b and 1c). The release of diethylene glycol is of concern because it is a known toxin(20) that makes up roughly 5 percent of the PCLF composition, an amount that currently exceeds the federal drug administration (FDA) limits. The source of diethylene glycol was determined to be from the PCL diol purchased commercially, where its role is as the initiator for the synthesis of polycaprolactone diol (1H NMR shown in Figure 1b). In order to circumvent the release of this degradation product two new PCLF compositions were synthesized using a linear PCL diol synthesized from 1,2 propane diol (PPD) also known as propylene glycol or a PCL triol synthesized from glycerol (GLY), the PCLF synthetic schemes are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Synthetic schemes of PCLFPPD and PCLFGLY

The propylene glycol or glycerol initiators were chosen because they are known to be biocompatible alcohols that can act as initiators for the polymerization of caprolactone(21). Glycerol occurs naturally in our bodies as the fatty acid linker that makes up triglycerides, and some glycerol containing biomaterials such as poly(glycerol sebacate) have been approved by the FDA(22). Propylene glycol is considered by the FDA to be generally recognized as safe(23), and is commonly used to deliver drugs intravenously. Although both molecules can be used to produce PCL and the subsequent PCLF, the resulting polymeric architectures are different. PPD results in linear PCL diol that is used as a precursor to synthesize linear PCLF (PCLFPPD). Glycerol results in a tri-branched PCL structure producing a highly branched PCLF (PCLFGLY) architecture. The differences in the polymeric architecture in turn affect the thermal, crystalline, and mechanical properties. The purpose of this manuscript is to show that PCLF produced from PCL initiated from 1,2 propane diol exhibits material properties similar to the previously studied PCLF, and to show that the material properties can be dramatically altered by effectively changing the polymer to a highly branched architecture. PCLF is a unique polymer that possesses a melting transition near the physiological temperature of 37°C. Because PCLF is a cross-linked material this transition represents the transformation from a crystalline to an amorphous material and dramatically affects the material properties of PCLF. By changing the polymeric architecture of PCLF from linear to branched crystallization can be suppressed resulting in softer PCLF materials. This manuscript reports the synthesis and characterization of the new PCLF compositions and characterizes the thermal, crystalline, rheological, and mechanical properties of the new PCLFPPD, PCLFGLY, and combinations thereof. Additionally, the critical question of a proper FDA approvable sterilization protocol is also addressed by autoclaving the PCLF materials and re-characterizing their material properties.

2. Methods

2.1 Materials

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Fisher or Aldrich in the highest available purity and used as is unless otherwise noted. Epsilon caprolactone was distilled under vacuum at 100 °C and stored under a nitrogen atmosphere until use. Fumaryl chloride was distilled before use.

2.2 Synthesis of polycaprolactones

Tin(II)ethylhexanoate (2.08 g, 0.005 mol) and 1,2 propane diol (9.8 g, 0.128 mol) were added to a Schlenk flask with a stir bar. The flask was pumped down and backfilled with N2 three times followed by the addition of caprolactone ((277.6 g, 2.43 mol) under N2. The reaction vessel was placed in a 140 °C oil bath for 1 h and then cooled to room temperature. The polymer melt solidified upon cooling and was dissolved in methylene chloride followed by precipitation into petroleum ether. The precipitated polymer was dried under vacuum at 60 °C and used as is.

2.3 Synthesis of polycaprolactone fumarate

Potassium carbonate (18.0 g, 0.13 mol) was added to a three neck flask fitted with a reflux condenser and purged with N2. Polycaprolactone diol (225 g, 0.11 mol) was dissolved in 600 mL of methylene chloride and added to the flask. Freshly distilled fumaryl chloride (17.2 g, 0.11 mol) dissolved in 20 mL methylene chloride was added dropwise to the reaction vessel and heated to reflux for 12 h. The reaction was then filtered to remove K2CO3, and precipitated into petroleum ether. The polymer was dried and used as is.

2.4 Polymer characterization

Polymer molecular weights were measured using gel permeation chromatography (GPC). The GPC system consists of a Waters 2410 refractive index detector, 515 HPLC pump, and 717 Plus autosampler, and a Styragel HR4E column. THF (tetrahydrofuran) was used as the eluent at 1 mL/min. Polystyrene standards with Mp of 474, 1060, 2950, 6690, 10600, 18600, and 39200 g mol−1 were used to determine the Mn and PDI. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a 300 MHz Varian NMR in CDCl3 or D2O for the degradation study.

2.5 Scaffold fabrication, sterilization, and degradation

Polycaprolactone fumarate (PCLF) (3.0 g) was dissolved in 1 mL methylene chloride. Photo-initiator Irgacure 819 (0.3 g)was dissolved in 3 mL methylene chloride, and 300 µL was added to the PCLF. The mixture was gently heated and vortexed to ensure a homogenous solution. The mixture was poured into glass molds for film and tube fabrication. The molds consisted of two glass plates separated by 0.5 mm. The molds containing polymer mixes were placed in a UV chamber and irradiated at 315–380 nm for 1 h to induce cross-linking. Scaffolds were swollen in acetone and methylene chloride to remove uncross-linked oligomers, then dried and used as is. Preformed films or tube scaffolds were packaged in sterilization pouches and autoclaved using a standard sterilization procedure of 125°C at 15 min steam. PCLF scaffolds were degraded by submersion in D2O containing 1 M NaOH at 37°C. Samples of D2O containing degradation products were removed after 24 h and analyzed directly using 1H NMR.

2.6 Thermal Analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed on a TA Instruments Q500 thermal analyzer. Samples were heated from room temperature to 800°C at a rate of 5°C min−1 under flowing nitrogen. Dynamic scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on a TA Instruments Q1000 differential scanning calorimeter. The sample underwent a heat-cool-heat cycle to ensure the same thermal history between samples. Samples were heated from room temperature to 100°C, then cooled to −80°C, and then heated to 150°C at a rate of 5°C min−1.

2.7 Swelling measurements

PCLF disks were dried under vacuum after fabrication. The dried scaffolds were weighed (Wd) and then submerged methylene chloride for 24 hours to allow equilibration. The films were blotted to remove excess methylene chloride from the surface and weighed (Ws). The swelling ratio was calculated as (Ws-Wd)Wd, where Ws is the weight after swelling and Wd is the dry weight.

2.8 Mechanical Testing

Mechanical testing was performed on a TA Instrument Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer 2980. To analyze the three-point bending properties of the materials, cylindrical tube geometry scaffolds were mounted in a three-point bending clamp and a preload force of 0.02 Newton (N) was applied. A ramping force rate 1.0 N/min was applied until material failure or 18 N was achieved. The TA instruments’ universal analysis software was used to identify the materials’ flexural modulus at 5% strain for all materials. For stretching and tensile measurements PCLF films were cut into a dog bone shape with a diameter of 2.1 mm and mounted in a tension clamp. The force applied on the sample started at 0.02 N and increased at a rate of 1.0 N min−1 until reaching either 18.0 N or the material’s failure point. Subsequently the tensile modulus of the scaffolds was determined by measuring the slope of the linear part of the stress/strain curve.

2.9 Rheometry

The linear viscoelastic properties of cross-linked PCLF polymer films were measured using a torsional dynamic mechanical analyzer (TA Instruments AR2000 rheometer). The linear viscoelastic region was determined using a strain sweep at a frequency of 1 Hz. A strain of 0.05% and oscillating stress 10 kPa were determined to be within the linear viscoelastic region for all polymers and were used for all further rheometry measurements. A frequency sweep from 0.1 to 628.3 rad/s was used to measure storage (G’) and loss (G”) moduli.

2.10 In Vitro Studies using PC12 cells

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated horse serum, 5% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, and 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin was used for PC12 cell culture. PCLFDEG, PCLFPPD and PCLFGLY were fabricated into disks of diameters 1.0 cm as described above. They were autoclave sterilized and fitted in 24-well plates. Autoclaved medical grade silicon tubing was inserted into the well to limit the surface area of the polymer disk to a diameter of 0.95 cm with a surface area of 0.71 cm2. The well was filled with media and incubated for 12 hours to remove any remaining impurities. PC12 cells were plated at a density of 30,000 cells cm−2. Experiments were performed with nerve growth factor (NGF; 50 ng mL−1) supplemented media. Cell viability was determined using MTS assay (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturers instructions. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm on a Molecular Devices spectra max plate reader.

Cell morphology was imaged by fluorescence microscopy. PC12 cells on polymer scaffolds were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 25 min, and then washed with PBS three times. Cells were permeablized in 0.1% Triton 100X for 3 min and then incubated in 10% horse serum in PBS for 1 h. Cells were stained in 1% rhodium phalloidin in 5% horse serum in PBS for 1 h and then washed with PBS three times. Nuclei were stained with DAPI just prior to mounting on a glass cover slip. Samples were imaged on an LSM 510 inverted confocal microscope and imaged at excitation wavelengths of 368 and 488 nm.

2.11 Statistics

All the material property characterization and cell culture experiments were run in triplicates unless otherwise noted. Using StatView (version 5.0.1.0, SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) a single factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine the significance of the results. Bonferroni’s method was used for multiple comparison tests when the global F-test was positive at an alpha level of 0.05 to determine differences among the experimental groups.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Synthesis of Polycaprolactone and Polycaprolactone Fumarate Polymers

Polycaprolactone precursor polymers were synthesized from biologically compatible alcohols 1,2 propane diol or glycerol. The ring opening polymerization of caprolactone is typically carried to 100% conversion and therefore the molecular weight of resulting PCL is determined by the monomer:initiator ratio. In this case a monomer to initiator ratio of 19:1 was used to produce PCL with molecular weights similar to the commercially available PCL synthesized from diethylene glycol (PCLDEG) with a target Mn of 2000 g mol−1. The PCL precursors were analyzed by GPC to ensure similar molecular weights. Figure 3 shows the GPC traces for PCL polymers are identical and the molecular weights are shown in Table 1. The molecular weights for the synthesized PCL and commercially available PCL are similar indicating quantitative consumption of caprolactone during the PCL synthesis. End group analysis using the terminal CH2-OH groups present in 1H NMR of the PCL polymers indicate the true PCL molecular weights are close to the desired Mn of 2000 g mol−1. Figure 4a,b contains 1H NMR spectra for PCLGLY and PCLPPD. The protons associated with the initiator moieties are visible after the polycaprolactone synthesis and have shifted from 3.3 and 3.8 to 4.15, 4.28 and 5.25 for PCLGLY, and 3.5 and 3.8 to 4.15 and 5.15 for PCLPPD. These shifts indicate that PCL initiated from both the primary and secondary alcohols on the PPD and GLY. The discrepancy between molecular weights determined by GPC and end group analysis is caused by the use of polystyrene standards for generation of the GPC calibration curve. PCLPPD is a linear polymer similar to commercially available PCLDEG, however PCLGLY is a tri-branched star polymer. Because the overall molecular weights of the PCL precursor are designed to be equal, the individual PCL chains are shorter for tri-branched PCLGLY than for linear PCLPPD or PCLDEG.

Figure 3.

GPC traces showing the PCL precursor polymers used in the synthesis of PCLF are virtually identical.

Table 1.

Molecular weight characterization

| Polymera |

bPredicted MW (g mol−1) |

cMn (g mol−1) |

PDI Mw/Mn |

d1H NMR (g mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCLDEG | 2000 | 3800 | 1.7 | 2308 |

| PCLPPD | 2245 | 3500–4400 | 1.4 | 2176 |

| PCLGLY | 2260 | 4000–5500 | 1.3 | 2386 |

| PCLFDEG | - | 11190 | 1.9 | - |

| PCLFPPD | - | 12200 | 2.0 | - |

| PCLFGLY | - | 10100 | 2.7 | - |

Characterization of polymer molecular weights.

The polymer composition described as polymerinitiator.

The predicted molecular weight based on monomer:initiator loading or the molecular weight given by commercial source.

Number average molecular weight measured by GPC using polystyrene standards.

Molecular weight determined by end group analysis.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures and 1H NMR showing a) PCLGLY b) PCLPPD. Peaks associated with the initiator and PCL are labeled on the chemical structures and spectra for identification. Chemical structures and spectra corresponding to c) PCLFGLY and d) PCLFPPD are shown and peaks corresponding to the fumarate double bond and esterification of the terminal alcohols in PCL are labeled.

The final PCLF polymers were produced by reacting fumaryl chloride with PCLPPD or PCLGLY. Because of the different polymeric architecture and the increased number of alcohols on PCLGLY the reaction times varied during the PCLF synthesis. Reactions with PCLPPD were refluxed for 12 h, while reactions using PCLGLY were monitored by GPC and a typical reaction time was 5 h. If the reaction time for PCLFGLY was extended to 12 h, a cross-linked polymer was recovered. This is due to the three available reaction sites per PCLGLY that allow it to act as a cross-linking agent. In this study all PCLF architectures had similar molecular weights ranging from 10–12 kg mol−1, however PCLFGLY had a broader PDI of 2.7.

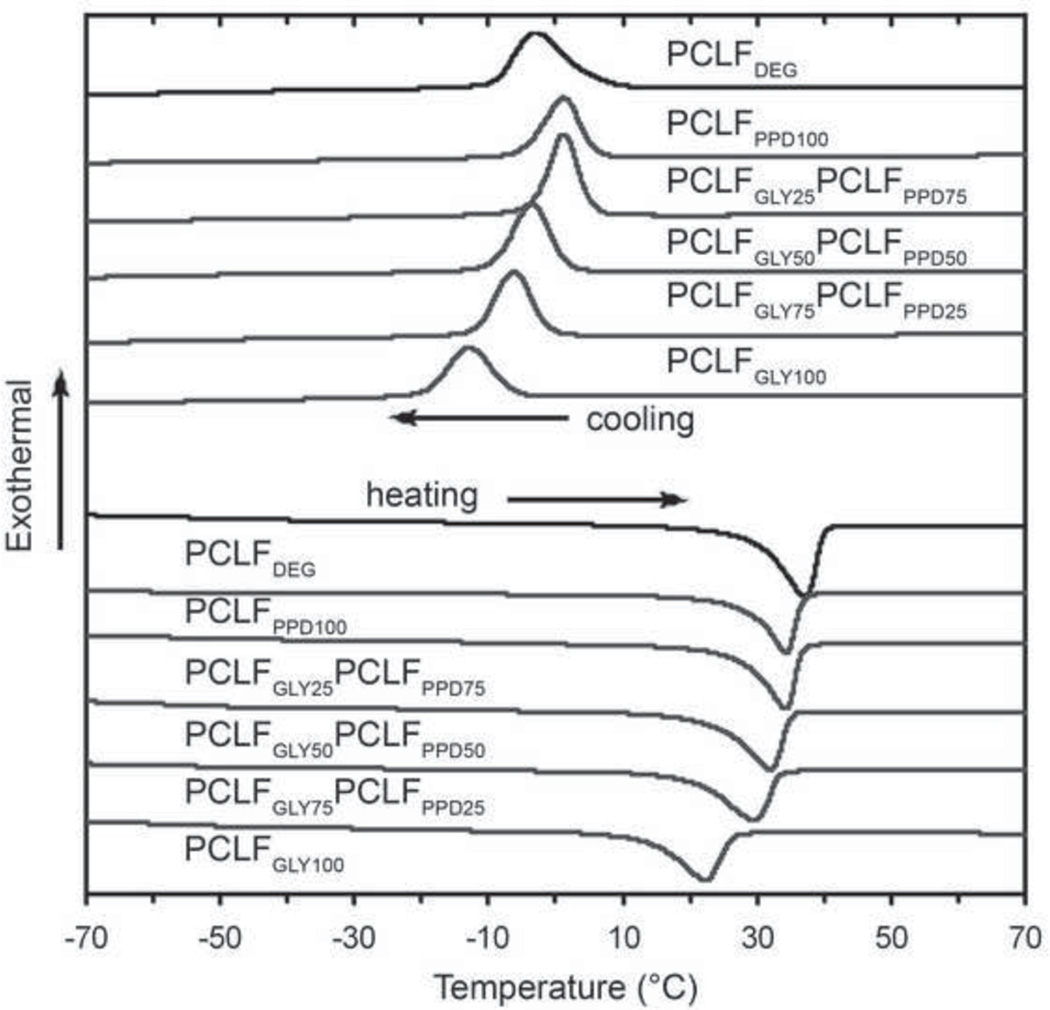

3.2 Characterization of Thermal Transitions and Crystalline Properties

PCLF is a cross-linked semi-crystalline material that possesses a Tm very close to physiological temperatures. The Tm represents the physical transition from a crystalline state (below Tm) to the amorphous state (above Tm). Because PCLF is cross-linked it does not flow above the Tm, however the mechanical properties dramatically change because the crystalline regions are a significant contributor to the material’s mechanical properties. Figure 5 shows the heating and cooling traces from differential scanning calorimetry experiments used to measure the thermal transitions of PCLF. Tm, Tc, Tg, ΔHm, ΔHc, and % crystallinity were analyzed and the results are shown in Table 2. The DSC data shows that PCLFPPD exhibits thermal and crystalline properties very similar to PCLFDEG. This is expected because the polymeric composition and architecture are identical except for differences in the initiators diethylene glycol and 1,2 propane diol that correspond to roughly 5% of the total composition. The branched architecture of PCLFGLY exhibits a lower Tm from 37.3°C to 22.5°C, reduced crystallinity from 30.1% to 22.8%, and decreased ΔHm from 40.7 to 30.7 J/g compared to PCLFDEG. This decrease in crystalline properties is attributed mainly to the effect of branching. Polymeric branching as well as increased cross-link density is known to disrupt the crystallization process by inhibiting the chain motion necessary for folding and ultimate crystal formation(24). PCLGLY is a tri-branched polymer and the resulting PCLFGLY theoretically has multiple branching points along the backbone, which is the likely reason for the decreased crystallinity. Additionally, because of branching the PCLGLY chain length is shorter (~7 monomer units) compared to the linear polymers (~9–10 monomer units) and will also contribute to lower crystalline properties. However, the shorter chain length is likely a minor contributor as it has been shown that linear PCLF with 5–6 monomer units per chain and cross-linked under the same conditions exhibits a Tm of 31.6°C and 30% crystallinity(17). The Tg values shown in Table 2 are virtually identical between all groups. The Tg is affected by chain mobility and can increase or decrease based on the type, length, and substituents that compose the branching arm. However, when the branch is nearly identical to the backbone polymer in terms of composition, length, and end groups the Tg has been shown to remain largely unaffected in other polymeric systems(24, 25).

Figure 5.

Differential scanning calorimetry showing the heating and cooling traces of different PCLF compositions

Table 2.

Thermal properties determined by Differential Scanning Calorimetry

| aPolymer Composition |

bTg (°C) |

bTm (°C) |

bTc °C) |

bΔHm J/g |

bΔHc J/g |

cPercent Crystallinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCLFDEG | −55.8 | 37.3 | −3.3 | 40.7 | 39.4 | 30.1 |

| PCLFPPD100 | −56.8 | 34.3 | 1.1 | 40.3 | 37.0 | 29.1 |

| PCLFPPD75 PCLFGLY25 | −57.7 | 34.3 | 1 | 37.7 | 34.3 | 27.9 |

| PCLFPPD50 PCLFGLY50 | −57.1 | 32.1 | −3.6 | 35.0 | 36.2 | 25.9 |

| PCLFPPD25 PCLFGLY75 | −56.7 | 29.9 | −6.3 | 32.1 | 35.1 | 23.8 |

| PCLFGLY100 | −56.3 | 22.5 | −12.9 | 30.7 | 29.6 | 22.8 |

Polymer composition of cross-linked PCLF.

The thermal properties Tg, Tm, Tc, ΔHm, ΔHc were determined from DSC heating and cooling runs.

Percent crystallinity was determined using the equation Xc = ΔHm/(dΦPCL eΔHm) × 100.

ΦPCL is the PCL fraction in PCLF.

ΔHm = 135 J/g for PCL(17, 29).

The thermal degradation profiles are shown in Figure 6 for the various PCLF scaffolds. All scaffolds show similar onsets of decomposition occurring at nearly 200°C. This shows that the onset of decomposition is independent of the molecular architecture of the polymers. The independence of thermal degradation from molecular architecture has been observed with other polyesters(25). Most importantly, the TGA indicates that these polymers are thermally stable well above the temperatures of 121 to 135 °C typically used for autoclave sterilization. The fact that these cross-linked PCLF polymers are thermally stable and do not flow above the Tm, are key characteristics of these scaffolds that are necessary for the autoclave sterilization process.

Figure 6.

Thermogravimetric analysis showing the thermal decomposition with increasing temperature of cross-linked PCLF scaffolds.

3.3 Swelling Ratio

The swelling ratio of cross-linked polymeric films indicates the relative cross-link density. The more highly cross-linked a material is, the less swelling occurs when placed in a theta solvent. Figure 7 shows differences in the swelling ratio of cross-linked PCLF materials. PCLFDEG has the highest swelling ratio indicating the lowest cross-linking density. Interestingly, the PCLFPPD50PDLFGLY50 has a similar swelling ratio, while both PCLFPPD and PCLFGLY have lower swelling ratios indicating a higher cross-link density.

Figure 7.

The swelling ratio of PCLF scaffolds in methylene chloride. The swelling ratio was determined by the equation (Ws-Wd)Wd, Ws is swollen weight and Wd is dry weight.

3.4 Mechanical Properties

The presence and percent crystalline regions in a polymer scaffold greatly affects the mechanical properties. Typically, increasing the crystallinity will increase a materials mechanical strength. Because of the differences in the crystalline properties of PCLFGLY, PCLFPPD, and PCLFDEG the flexural and tensile moduli were measured. Figure 8a shows the stress strain plots of the PCLF materials in stretching mode. The stress strain plot shows the distinctly different nature of the polymeric materials. PCLFDEG and formulations containing any amount of PCLFPPD exhibit rubber like properties with reversible elastic properties at low strains with a typical yield point below 15%. The PCLFGLY100 stress strain curve shows dramatically different elastomeric properties with high strains under low stress. The results of the tensile and flexural moduli measurements for 1–5% strain are shown in Figure 8b. PCLFDEG has tensile and flexural moduli of 130 ± 12 MPa and 78 ± 14 MPa respectively. PCLFPPD exhibits slightly decreased moduli 128 ± 22 and 51 ± 6 while PCLFGLY shows significantly lower tensile and flexural moduli of 4.5 ± 1 and 8.9 ± 1.7 MPa respectively. Statistical analysis shows that PCLFPPD and PCLFDEG are not different. However, the PCLFGLY exhibits a significantly lower tensile and flexural modulus. By blending the PCLFGLY and PCLFPPD the moduli of the resulting scaffolds can be tailored to an intermediate desired value.

Figure 8.

a) stress-strain curves for the different compositions of PCLF in stretching mode. b) tensile and flexural moduli for the different PCLF compositions. *Represent statistically significant differences between groups compared to PCLFPPD (p < 0.05). #Represent statistically significant differences between groups compared to PCLFDEG(p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed between PCLFPPD and PCLFDEG. PCLF group names were truncated by excluding PCLFPPD% to fit in the chart.

Although there are no is well defined range of mechanical properties that a nerve conduit must possess to be considered ideal, there are general criteria that a nerve conduit must fulfill. These include mechanical resistance to lumen closure or compression, flexibility, suturability, and degradability. PCLFDEG has been shown to support regeneration of segmental nerve defects. It resists lumen closure and holds a suture well because it is a high modulus material. However these favorable characteristics come at the expense of flexibility. PCLFGLY on the other hand is a lower modulus material and is more compliant. Therefore PCLFGLY nerve conduits are more flexible and elastic, and if necessary can be bent or stretched with little force thereby limiting the trauma to the nerve that would occur with a stiffer material. The question of flexibility and elongation is not whether the conduit deforms or not, but rather how much force it takes to deform the conduit. It is likely that a nerve conduit would experience a strain induced deformation rather than a stress induced deformation. A potential example of this could be the bending of a nerve conduit around a joint. The amount of strain the conduit/nerve would undergo would be the same with either material, however the amount of force/stress inflicted on the nerve would be higher for the higher modulus materials, in this case PCLFDEG and PCLFPPD. This means that a higher modulus conduit is more likely to propagate a higher force to the nerve than a low modulus material potentially damaging the regenerating nerve. Therefore we believe that PCLFGLY has the better mechanical properties compared to PCLFDEG or PCLFPPD for nerve conduit applications.

3.5 Rheological Properties

Rheology was used to analyze the viscoelastic properties of the different PCLF materials and subsequent blends. Frequency sweep and creep experiments were used to measure the storage and loss moduli as well as the materials compliance and recovery behavior. These parameters were used to investigate effects of the different crystalline microstructures on the cross-linked PCLF viscoelastic behavior, and were also used to evaluate material changes after autoclave sterilization. The linear elastic regions of PCLF materials shown in Figure 9a,b were determined by performing strain sweeps from 0.1% to 100% strain at a frequency of 1 Hz. The linear region where G’ is independent of strain (Figure 9a) or oscillating stress (Figure 9b) were used to determine overlapping linear viscoelastic regions for all materials. All frequency sweeps were performed at 37°C using 0.05% strain and the storage modulus (G’) or loss modulus (G”) vs. frequency are shown in Figure 9c, d for all PCLF compositions. Frequency sweeps reveal that G’ and G” showed no frequency dependence for all materials except for PCLFGLY that exhibits slight frequency dependence behavior. This indicates that all scaffolds possess a well ordered three-dimensional structure. PCLFDEG and PCLFPPD have the highest G’ of 14.7 MPa and 12.4 MPa respectively at 100 rad/s. G’ decreases with increasing amounts of PCLFGLY to 3.7 MPa for PCLFPPD25PCLFGLY75, and PCLFGLY100 has a G’ of 0.3 MPa, over an order of magnitude lower than all other compositions. The differences in G’ observed between PCLF materials agree with the crystallization data and show that the increased shear modulus correlates with increasing crystallinity and Tm transitions. G” exhibits frequency dependant behavior for PCLFGLY, but is mainly independent for all other PCLF compositions. G” measurements are an order of magnitude lower than G’, and this relationship is plotted as tan δ in Figure 9e. Tan δ is used to evaluate a materials elasticity and is plotted as G”/G’ vs. frequency. Figure 9e shows all PCLF materials have tan δ values around 0.1 indicating the materials exhibit similar viscoelastic behavior despite the differences in G’ and G” values. These low tan δ values are characteristic of a widely cross-linked polymeric material(26). This accurately describes the nature of the PCLF cross-linking due to long PCL segments separating the individual cross-linked fumarate groups.

Figure 9.

Rheological measurements for PCLF compositions. Linear viscoelastic regions as a function of a) % strain and b) oscillating stress. c) Storage modulus, d) loss modulus, and e) tanδ as a function of frequency. f) Creep and recovery of PCLF films with an applied stress of 10 kPa.

In order to further demonstrate a difference in the material properties of the branched vs. linear PCLF scaffolds a creep experiment was performed to illustrate the compliance and recovery properties. The creep experiments shown in Figure 9f demonstrate that the materials possess distinctly different compliance characteristics when a constant stress of 10 kPa is applied. PCLFDEG and PCLFPPD exhibited shear strains of 0.11–0.27%. These strains are 1/36–1/14 of the 4.0% shear strain experienced by PCLFGLY100.

3.5 Autoclave Sterilization

A clinically relevant sterilization method is critical for translation of biomaterials from basic science into a clinical product. Despite its necessity, this stage of product development is frequently circumvented by alcohol sterilization during initial studies. The easiest FDA approved sterilization procedure is autoclave sterilization because it is quick and effective. However, for easily degradable and non cross-linked polymeric materials it can destroy the scaffold geometry or detrimentally affect the material properties and ultimate device performance. However, Riepe et al showed that commercially available polyester vascular grafts and prosthesis could be autoclaved without significant changes to the mechanical properties(27). Therefore we examined the effect of autoclave sterilization on PCLF material properties. A standard autoclave procedure was used with a temperature of 125°C for 15 min in the presence of steam. Immediately after autoclave sterilization all materials appear transparent and slowly turned opaque as the scaffolds cooled. The three-dimensional structure was maintained and no noticeable changes in the scaffold were observed. In order to determine material changes as a result of autoclave sterilization the PCLF thermal (Table 3), mechanical (Figure 10), and rheological properties (Figure 11) were characterized and compared to the properties prior to autoclave treatment. Table 3 shows the DSC results and changes in thermal transitions for PCLF materials after autoclave. The glass transitions decreased by 0.4 – 1.4°C, the melting temperatures increased 1.5 – 3.5°C, and the crystallization temperatures increased from 4.7 – 16.3°C. The percent crystallization, ΔHm, and ΔHc increases ranged from 2.3 – 11.6%, 3.1 – 15.6 J/g, and 3.1–14.2 J/g respectively. This data indicates increased crystalline properties. The increase in the crystalline nature of the scaffolds is likely due to subtle hydrolysis of PCLF ester bonds resulting in decreased cross-linking. For all parameters PCLFGLY consistently exhibited the least change due to the autoclave sterilization process.

Table 3.

Effect of Autoclave Sterilization on Thermal Properties

| Polymer Compositiona | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) | Tc (°C) | ΔHm J/g | ΔHc J/g | Percent Crystallinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCLFDEG | −57.2 (−1.4) |

39.4 (2.1) |

13.0 (16.3) |

56.3 (15.6) |

53.6 (14.2) |

41.7 (11.6) |

| PCLFPPD100 | −58.2 (−1.4) |

37.8 (3.5) |

9.3 (8.2) |

44.9 (4.6) |

48.3 (11.3) |

33.2 (4.1) |

| PCLFPPD75PCLFGLY25 | −58.6 (−0.9) |

36.7 (2.4) |

9.7 (8.7) |

44.7 (7.0) |

45.0 (10.7) |

33.1 (5.2) |

| PCLFPPD50PCLFGLY50 | −57.5 (−0.4) |

33.9 (1.8) |

5.2 (8.8) |

38.1 (3.1) |

39.3 (3.1) |

28.2 (2.3) |

| PCLFPPD25PCLFGLY75 | −57.1 (−0.4) |

32.0 (2.1) |

5.2 (11.5) |

43.1 (11.0) |

45.0 (10.1) |

32.0 (8.2) |

| PCLFGLY100 | −56.8 (−0.5) |

24 (1.5) |

−8.2 (4.7) |

34.1 (3.4) |

37.6 (8.0) |

25.3 (2.5) |

Thermal characterization of cross-linked PCLF scaffolds after autoclave sterilization. The values measured are shown on top, and the difference between the values measured before and after autoclave sterilization are in ( ).

Figure 10.

The elastic moduli of PCLF materials before and after autoclave sterilization. The PCLF names were truncated to fit in the graph. Statistical analysis was performed on each group to evaluate the effect of the sterilization. No significant changes due to autoclave sterilization were observed in the elastic moduli for any group (p < 0.05).

Figure 11.

Rheological measurements for PCLF compositions after autoclave sterilization. a) Storage modulus, b) loss modulus, and c) tan δ as a function of frequency. d) Creep and recovery of PCLF films with an applied stress of 10 kPa.

Material properties showed subtle changes after autoclave sterilization. The elastic moduli of sterilized PCLF samples were not statistically different from before receiving sterilization. Rheological measurements were performed 1 day after sterilization and the results are shown in Figure 11. Only subtle differences were observed for G’, G” and tan δ for all materials when compared to the properties before sterilization. For instance G’ for PCLFGLY decreased from 2.6 MPa to 1.5 MPa at 100 rad/s after sterilization. This difference in G’ and G” translated into increased compliance behavior when a constant shear stress was applied as shown in Figure 11d. PCLFGLY exhibited an increase in compliance (J) from 4.0 × 10−6 to 6.2 × 10−6 1/pa. Other PCLF materials also showed changes in the G’ and G” that changed their compliance behavior, although no PCLF exhibited a behavior drastically different from those measured before the autoclave sterilization process. The fact that only subtle changes in PCLF material properties were observed after autoclave sterilization is attributed to PCLF being hydrophobic, cross-linked, and more slowly degrading than other polyesters.

3.6 In vivo PC 12 cell attachment

PC12 cells were used to verify that cells attach to the PCLFGLY and PCLFPPD equally well as the extensively studied PCLFDEG. Figure 12 shows that there were no significant differences in the attachment of PC12 cells on the different PCLF materials. The PC12 cells showed similar cellular morphologies with many cells exhibiting extending neurites. It is commonly known that a materials modulus can affect cell attachment and neurite extension. However PC12 cells have only been shown to have modulus dependant responses for materials with modulus below 250 kPa(28). The similar cell response between the different materials is attributed to the fact the chemical composition of the polymers is similar, and that differences in the moduli of the materials is outside the range that influences PC12 cell behavior.

Figure 12.

PC12 cell attachment and morphology. a) MTS assay showing number of cells attached after 24 h. No significant differences were observed in the number of cells attached. Fluorescence microscopy showing PC12 cell morphology after 24 h on b) PCLFPPD100 c) PCLFPPD75PCLFGLY25 d) PCLFPPD50PCLFGLY50 e) PCLFPPD25PCLFGLY75 f) PCLFGLY100 g) PCLFDEG.

4 Conclusions

PCLF materials were successfully synthesized from biocompatible 1,2 propane diol or glycerol initiated PCL precursors. This eliminates the toxic diethylene glycol component of previous PCLF compositions that is released upon degradation. The linear PCLFPPD polymeric scaffolds maintain similar thermal, rheological, and mechanical properties to the previously studied PCLFDEG. The branched PCLFGLY possesses distinctly different material properties. The branched structure of PCLFGLY disrupts crystallization resulting in reduced crystallinity and lowers the Tm below physiological temperatures. This makes PCLFGLY amorphous at physiological temperatures resulting in lower elastic moduli and an increasingly compliant material. Additionally it was shown that these PCLF materials can be sterilized by autoclave sterilization without statistically significant changes in the mechanical properties, thereby removing one more hurdle in the translation of these biomaterials to clinically acceptable products for both bone and nerve regeneration applications.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NIH training grant 1T32AR056950-01, the NIH Loan Repayment Program, NIBIB PAR56212, and the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine by DOD activity contract # W81XWH-08-2-0034.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

A preliminary patent application has been filed with the USPTO, and the technologies have been licensed to BonWrx.

References

- 1.Wang S, Kempen DHR, Yaszemski MJ, Lu L. The roles of matrix polymer crystallinity and hydroxyapatite nanoparticles in modulating material properties of photo-crosslinked composites and bone marrow stromal cell responses. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3359–3370. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang S, Yaszemski MJ, Knight AM, Gruetzmacher JA, Windebank AJ, Lu L. Photo-crosslinked poly(ε-caprolactone fumarate) networks for guided peripheral nerve regeneration: Material properties and preliminary biological evaluations. Acta Biomaterialia. 2009;5:1531–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandez JM, Molinuevo MS, Cortizo AM, McCarthy AD, Cortizo MS. Characterization of poly(epsilon-caprolactone)/polyfumarate blends as scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 21:1297–1312. doi: 10.1163/092050609X12517190417632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang K, Cai L, Hao F, Xu X, Cui M, Wang S. Distinct cell responses to substrates consisting of poly(epsilon-caprolactone) and poly(propylene fumarate) in the presence or absence of cross-links. Biomacromolecules. 11:2748–2759. doi: 10.1021/bm1008102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, Kempen DH, Simha NK, Lewis JL, Windebank AJ, Yaszemski MJ, Lu L. Photo-cross-linked hybrid polymer networks consisting of poly(propylene fumarate) and poly(caprolactone fumarate): controlled physical properties and regulated bone and nerve cell responses. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1229–1241. doi: 10.1021/bm7012313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan J, Li J, Runge MB, Dadsetan M, Chen Q, Lu L, Yaszemski MJ. Cross-linking characteristics and mechanical properties of an injectable biomaterial composed of polypropylene fumarate and polycaprolactone co-polymer. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 22:489–504. doi: 10.1163/092050610X487765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharifi S, Mirzadeh H, Imani M, Atai M, Ziaee F. Photopolymerization and shrinkage kinetics of in situ crosslinkable N-vinyl-pyrrolidone/poly(epsilon-caprolactone fumarate) networks. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;84:545–556. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishna L, Jayabalan M. Synthesis and characterization of biodegradable poly (ethylene glycol) and poly (caprolactone diol) end capped poly (propylene fumarate) cross linked amphiphilic hydrogel as tissue engineering scaffold material. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2009;20 Suppl 1:S115–S122. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3493-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Yaszemski MJ, Lu L. Three-dimensional porous biodegradable polymeric scaffolds fabricated with biodegradable hydrogel porogens. Tissue Engineering - Part C: Methods. 2009;15:583–594. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai L, Wang S. Parabolic dependence of material properties and cell behavior on the composition of polymer networks via simultaneously controlling crosslinking density and crystallinity. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7423–7434. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S, Lu L, Gruetzmacher JA, Currier BL, Yaszemski MJ. A biodegradable and cross-linkable multiblock copolymer consisting of poly(propylene fumarate) and poly(poly(ε-caprolactone): Synthesis, characterization, and physical properties. Macromolecules. 2005;38:7358–7370. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharifi S, Mirzadeh H, Imani M, Ziaee F, Tajabadi M, Jamshidi A, Atai M. Synthesis, photocrosslinking characteristics, and biocompatibility evaluation of N-vinyl pyrrolidone/polycaprolactone fumarate biomaterials using a new proton scavenger. Polymers for Advanced Technologies. 2008;19:1828–1838. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharifi S, Mirzadeh H, Imani M, Rong Z, Jamshidi A, Shokrgozar M, Atai M, Roohpour N. Injectable in situ forming drug delivery system based on poly(ε-caprolactone fumarate) for tamoxifen citrate delivery: Gelation characteristics, in vitro drug release and anti-cancer evaluation. Acta Biomaterialia. 2009;5:1966–1978. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Runge MB, Dadsetan M, Baltrusaitis J, Knight AM, Ruesink T, Lazcano EA, Lu L, Windebank AJ, Yaszemski MJ. The development of electrically conductive polycaprolactone fumarate-polypyrrole composite materials for nerve regeneration. Biomaterials. 31:5916–5926. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moroder P, Runge MB, Wang H, Ruesink T, Lu L, Spinner RJ, Windebank AJ, Yaszemski MJ. Material properties and electrical stimulation regimens of polycaprolactone fumarate-polypyrrole scaffolds as potential conductive nerve conduits. Acta Biomater. 7:944–953. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jabbari E, Wang S, Lu L, Gruetzmacher JA, Ameenuddin S, Hefferan TE, Currier BL, Windebank AJ, Yaszemski MJ. Synthesis, material properties, and biocompatibility of a novel self-cross-linkable poly(caprolactone fumarate) as an injectable tissue engineering scaffold. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2503–2511. doi: 10.1021/bm050206y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, Yaszemski MJ, Gruetzmacher JA, Lu L. Photo-Crosslinked Poly(epsilon-caprolactone fumarate) Networks: Roles of Crystallinity and Crosslinking Density in Determining Mechanical Properties. Polymer (Guildf) 2008;49:5692–5699. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Ruiter GC, Malessy MJ, Yaszemski MJ, Windebank AJ, Spinner RJ. Designing ideal conduits for peripheral nerve repair. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26:E5. doi: 10.3171/FOC.2009.26.2.E5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang X, Lim SH, Mao HQ, Chew SY. Current applications and future perspectives of artificial nerve conduits. Exp Neurol. 223:86–101. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geiling EMK, Cannon PR. Pathologic effects of elixir of sulfanilamide (diethylene glycol) poisoning. JAMA. 1938;111:919–926. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hao J, Liu Y, Zhou S, Li Z, Deng X. Investigation of nanocomposites based on semi-interpenetrating network of [L-poly (epsilon-caprolactone)]/[net-poly (epsilon-caprolactone)] and hydroxyapatite nanocrystals. Biomaterials. 2003;24:1531–1539. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00516-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhowmick AK. Current Topics in Elastomer Research. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Administration, F. a. D. GRAS status of propylene glycol and propylene glycol monostearate. Fed Regist. 1982;47:27810. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voit BI, Lederer A. Hyperbranched and highly branched polymer architectures--synthetic strategies and major characterization aspects. Chem Rev. 2009;109:5924–5973. doi: 10.1021/cr900068q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wooley KL, Fréchet JMJ, Hawker CJ. Influence of shape on the reactivity and properties of dendritic, hyperbranched and linear aromatic polyesters. Polymer. 1994;35:4489–4495. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mezger TG. The Rheology Handbook. 2nd ed. Hannover, Germany: Vincentz; 2006. 'Vol. ' p. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riepe G, Whiteley MS, Wente A, Rogge A, Schroder A, Galland RB, Imig H. The effect of autoclave resterilisation on polyester vascular grafts. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;18:386–390. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.1999.0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nemir S, West JL. Synthetic materials in the study of cell response to substrate rigidity. Ann Biomed Eng. 2009;38:2–20. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polymer handbook. 3rd ed. New York: Wiley; 1989. ed.; 'Vol.' p. [Google Scholar]