Abstract

Background

Feeding problems are common in dementia, and decision-makers have limited understanding of treatment options.

Objectives

To test whether a decision aid improves quality of decision-making about feeding options in advanced dementia.

Design

Cluster randomized controlled trial.

Setting

24 nursing homes in North Carolina

Participants

Residents with advanced dementia and feeding problems and their surrogates.

Intervention

Intervention surrogates received an audio or print decision aid on feeding options in advanced dementia. Controls received usual care.

Measurements

Primary outcome was the Decisional Conflict Scale (range 1–5) measured at 3 months; other main outcomes were surrogate knowledge, frequency of communication with providers, and feeding treatment use.

Results

256 residents and surrogate decision-makers were recruited. Residents’ average age was 85; 67% were Caucasian and 79% were women. Surrogates’ average age was 59; 67% were Caucasian, and 70% were residents’ children. The intervention improved knowledge scores (16.8 vs 15.1, p<0.001). After 3 months, intervention surrogates had lower Decisional Conflict Scale scores than controls (1.65 vs. 1.90, p<0.001) and more often discussed feeding options with a health care provider (46% vs. 33%, p=0.04). Residents in the intervention group were more likely to receive a dysphagia diet (89% vs.76%, p=0.04), and showed a trend toward increased staff eating assistance (20% vs.10%, p=0.08). Tube feeding was rare in both groups even after 9 months (1 intervention vs. 3 control, p=0.34).

Limitations

Cluster randomization was necessary to avoid contamination, but limits blinding and may introduce bias by site effect.

Conclusion

A decision aid about feeding options in advanced dementia reduced decisional conflict for surrogates and increased their knowledge and communication about feeding options with providers.

Keywords: dementia, decision-making, nutrition, nursing home

INTRODUCTION

Dementia causes progressive impairment in memory and other cognitive domains. Life expectancy ranges from 4–9 years after an initial dementia diagnosis.1,2,3 Advanced dementia is characterized by profound memory deficits, inability to recognize family members, sparse speech, incontinence, and dependency for all activities of daily living including eating.4 Feeding problems are common; in the prospective CASCADE Study (Choices, Attitudes and Strategies for Care of Advanced Dementia) of 323 nursing home residents with advanced dementia, 86% developed difficulty with feeding.5 Altered taste and smell reduce interest in food, apraxia and attention deficits interfere with self-feeding, and dysphagia causes choking or food avoidance.6,7,8 Feeding problems cause weight loss, dehydration, poor wound healing, aspiration pneumonia, and death.

Families of dementia patients engage in choices about feeding more often than any other treatment, but report the quality of decision-making is poor.9 Decisions can be ethically and emotionally difficult. Nutrition is an ordinary rather than extraordinary treatment, and is seen as a way to nurture and comfort someone who is ill.10 The fundamental choice is between tube feeding or assisted oral feeding, and a recent 5-state study found 11% of persons dying with dementia had a feeding tube.11 Controlled observational studies show tube feeding does not improve survival, aspiration or wound healing, but this information is not routinely shared with decision-makers. 12,13,14,15,16 Families and physicians may expect benefits from tube feeding that exceed actual outcomes, and clinical consent discussions often focus on procedural risks, not outcomes and alternatives.17,18,19,20

Decision aids provide patients and families with structured information about a clinical choice, and are used to enhance clinical decision-making. They are designed to present balanced, evidence-based information about the risks, benefits, and alternatives of a particular decision. 21 Decision aids improve time efficiency and quality of informed decision-making by increasing knowledge, reducing decisional conflict, and promoting evidence-based treatments. 22,23,24,25,26 Important decisions must be made for cognitively impaired patients, yet decision aids are rarely designed for surrogates. Mitchell tested a decision aid on tube feeding using a pre-post study design with 15 surrogates. This decision aid improved knowledge and reduced decisional conflict, but did not use randomized controls or examine effects over time.27 Extending this work, we conducted a cluster randomized trial in nursing homes; cluster randomization was required to minimize contamination across providers, and to parallel the adoption of decision support in practice organizations. The research objective was to test whether a decision aid, compared to usual care, could improve the quality of decision-making by surrogates for persons with advanced dementia.

METHODS

Design Overview

The study design was a cluster randomized trial, with randomization at the level of the nursing home. Surrogates in the intervention sites received and reviewed the decision aid, compared to usual information and decision-making in the control sites. Outcomes were collected and analyzed at the level of the individual.

Setting and Participants

The trial was conducted in 24 North Carolina nursing homes; detailed trial methods are published.28 Sites were eligible if they served residents with dementia; 28% had a dementia unit. Site administrators and physicians gave assent for resident participation. Nursing home residents with advanced dementia and feeding problems were enrolled with their surrogate decision-makers from August 2007 through July 2009. Residents aged > 65 who scored 5–6 on the most recent Cognitive Performance Scale in the Minimum Data Set (MDS) were assessed for eligibility.5,28,29 Advanced dementia was confirmed by chart diagnosis, and dementia severity staged 6–7 on the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) by the day shift nurse who most often provided care.30,31 Eligible residents also had chart evidence of feeding problems with at least one of the following: poor intake, dysphagia or weight loss. Poor intake meant taking < 75% of meals over the past 14 days. Dysphagia was defined as difficulty swallowing, choking on food or liquid, dehydration, dysphagia, or aspiration. Weight loss was defined as >5% of body weight in 30 days or >10% in 6 months. Residents were excluded if they had a feeding tube, a “Do Not Tube Feed” order, were enrolled in hospice, or had weight loss associated with diuresis.

Eligible surrogates were identified as the resident’s guardian, Health Care Power of Attorney, or the primary family contact and most likely to be involved in clinical decision-making. Surrogates who responded to an informational letter gave informed consent for themselves and the resident; consent language was modified for intervention or control condition.

All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, and for individual research sites by the IRBs of Alamance Regional Hospital and the East Carolina University Brody School of Medicine. A Data Safety Monitoring Committee reviewed preliminary data, adverse events and mortality every 6 months throughout the study period.

Randomization

Nursing home sites with varied organizational characteristics were recruited and randomized in pairs matched on variable associated with tube feeding rates -- for profit or non-profit status, size, and percent African-American residents. Paired nursing homes were assigned to intervention or control conditions by computerized random number generation conducted by a single investigator (JG). Randomization was completed and allocation concealed prior to enrollment. Due to cluster randomization, data collectors were not blinded to group assignment. Information shared with physicians and other health care providers was specific to intervention or control assignment, and direct health care providers were told the general purpose of the study but blinded to outcome measures.

Intervention and Control Conditions

Surrogates in intervention sites received a structured decision aid providing information about dementia, feeding options and the outcomes, advantages and disadvantages of feeding tubes or assisted oral feeding. It provided information on feeding for comfort near the end of life, and discussed the surrogate role in decisions. Content was updated from Mitchell’s published decision aid and revised to a 6th grade reading level with simple sentence structure and size 16–20 font. Information was structured using the International Patient Decision Aid Standards statement.21 Surrogates reviewed the decision aid during their enrollment interview in print format; persons with vision or literacy limitations were given the option of an audiorecording with words on a computer screen. Research assistants were present, but trained not to provide additional information; review of the decision aid took an average of 20 minutes. Surrogates received the print decision aid to take home, and research assistants prompted them to discuss it with health care providers.

Control surrogates received usual care, including any information from health care providers. All other study procedures were identical for intervention and control participants.

Data Collection

Surrogates had in-person interviews with trained research assistants at enrollment, and telephone interviews at 1 and 3 months. Structured nursing home chart reviews were completed at enrollment, 1 and 3 months, and brief chart reviews at 6 and 9 months for additional follow-up data on tube feeding, weight loss and mortality. All analyses rely on data from the primary end-points of 3 and 9 months; when data was missing at 3 or 9 months, values were extrapolated from 1 and 6 months respectively. When a resident died, the next chart review was completed on schedule but the next surrogate interview used modified wording and permitted somewhat more flexible scheduling to acknowledge death and bereavement; these decedent interviews omitted the Decisional Conflict Scale as the items have not been revised or validated for use after death occurs.

Measures

The primary outcome was surrogate decisional conflict at 3 months; other main outcomes were knowledge about dementia and feeding options, frequency of communication with health care providers, and use of feeding treatments. Decisional conflict was measured using the validated Decisional Conflict Scale. During the 3 month interview, surrogates were asked to consider the choice of feeding tube placement or assisted feeding by mouth for the resident with dementia. The interviewer introduced the choice with “Please listen to the following comments about deciding about medical treatments, in this case feeding tube placement or assisted feeding in dementia. I’m going to give you this card that shows the choices. For each question I ask, please show me how strongly you agree or disagree with these comments.” The scale has 16 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater conflict; subscales measure uncertainty, effective decision-making, and factors contributing to uncertainty.32 Examples of items include “I am clear about the best choice for [RESIDENT NAME]” and “I feel I have made an informed choice.”

Knowledge was measured during the enrollment interview for intervention and control surrogates; intervention surrogates answered knowledge items after review of the decision aid. Surrogates answered 19 true / false items about dementia and feeding options (range, 0–19, higher scores indicating better knowledge). Knowledge was also measured with the Expectation of Benefit Index. Used in a previous study, this index consists of 11 Likert-scaled items measuring potential benefits from tube feeding. Scores range from 1–4, with lower scores indicating better knowledge.17 Frequency of discussion about feeding options was measured at 3 months using surrogate report of these discussions with physicians, nurse practitioners or physician assistants. Three-month follow-up interviews also included Likert-scaled instruments measuring decision-making satisfaction and regret, using the 6-item Satisfaction with Decision Scale (range 1–5, lower scores indicate greater satisfaction), and a five-item Decisional Regret index (range 0–100, higher scores indicate greater regret).33,34

Chart review variables included resident demographics, functional status using the MDS Activities of Daily Living scale (range 0–28, higher scores indicate greater dependence), and all variables composing the MDS prognostic risk score for advanced dementia (range 0–19, higher scores indicate increased 6-month mortality risk).35 Documentation of feeding problems came from MDS variables for chewing or swallowing problems, weight loss or poor intake of meals, and from review of nursing, physician, speech therapy and dietary notes. Data on use of feeding treatments came from review of medical orders and nursing, physician and dietary notes for information on new feeding tubes, new orders not to use feeding tubes, and new oral feeding treatments including diet modification, dysphagia diets, high calorie supplements, specialized staff assistance, specialized utensils, and positioning. Chart reviews were also used to ascertain resident weight loss, death and date of death. Because explicit decisions about tube feeding were rare at 3 months, the original study protocol was modified to add brief 6 and 9 month chart reviews for additional data on tube feeding, orders not to tube feed, weight loss and mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Surrogates were the primary unit of analysis, and all analyses used intention-to-treat assignment. Intervention and control surrogates were compared at 3 months for differences in decisional conflict scores, frequency of communication with health care providers and feeding treatments. Knowledge scores from enrollment interviews were compared between intervention surrogates who reviewed the decision aid and control surrogates. Additional data were used to compare intervention and control residents’ cumulative rates of tube feeding, orders not to use tube feeding, weight loss and death at 9 months. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous outcomes. We fit linear regression models for continuous outcomes and logistic regression models for binary outcomes to adjust the intervention effect for any baseline differences observed after randomization. Results are presented as covariate adjusted means or percents. The standard errors for all analyses were corrected for intraclass correlation due to cluster effects by nursing home. Pre-specified secondary analyses were conducted to examine the effect of religiosity or race and ethnicity on outcomes. The trial was powered for a sample size of 250, based on a 12% difference in the Decisional Conflict Scale between the control and intervention arms, assuming intra-class correlation up to r=0.05.

RESULTS

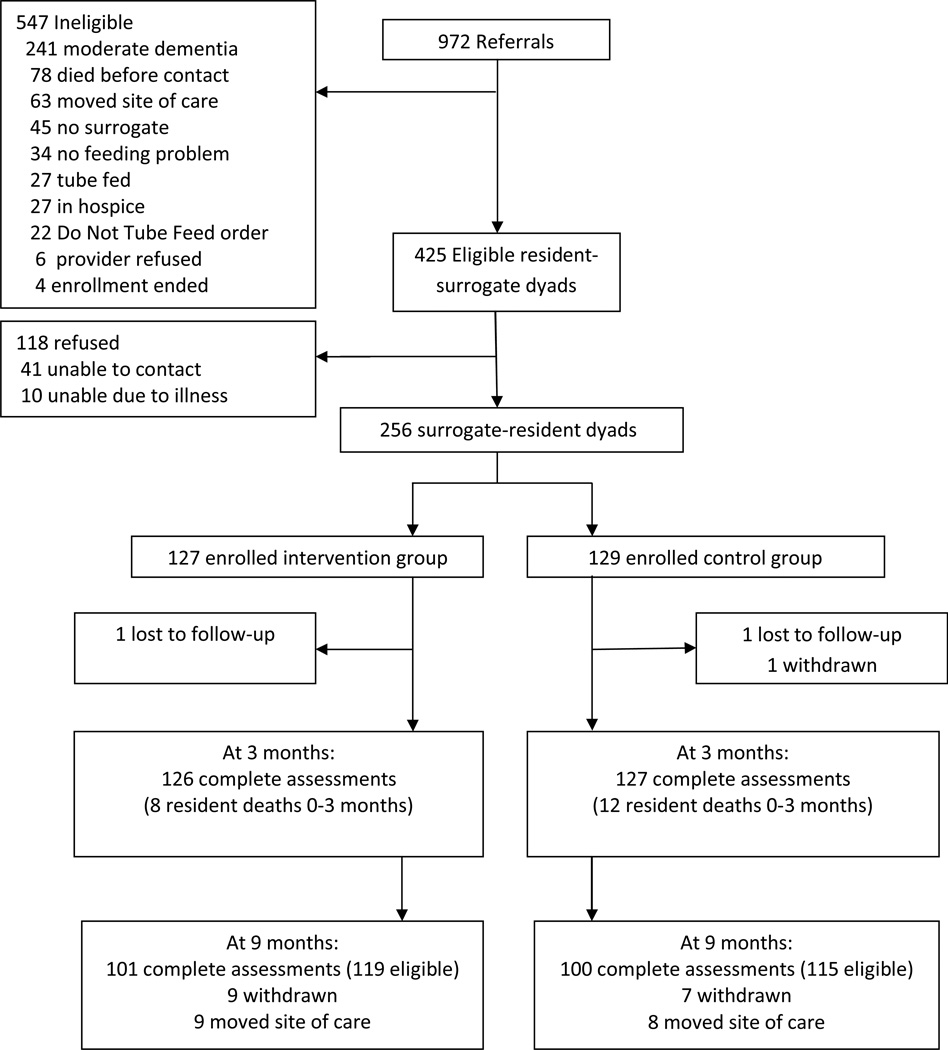

Twenty-nine nursing homes were approached, and 24 participated; no nursing home withdrew from the study. During the enrollment period 972 residents with dementia were screened, and 425 were eligible. (Figure) Common reasons for ineligibility included: not having advanced dementia (n=241), death (n=78) or moving (n=63) prior to mailing of the invitation letter, no surrogate (n=45) or absence of feeding problems (n=32). Of 425 eligible resident-surrogate dyads, 256 were enrolled (60%), with 127 intervention and 129 control participants. Residents and surrogates who did not participate were similar to those who enrolled; however, non-participating surrogates more often lived out of state (9% vs 5%, p<0.001).28 Baseline data collection was completed for all enrolled residents and surrogates, and for 99% of residents and surrogates at 3 months. The 9 month chart review was completed for 86%; remaining surrogates could not be contacted for revised consent.

Figure.

Improving Decision-Making Recruitment and Retention

The average age of residents with advanced dementia was 85, and most were women. (Table 1) Surrogate decision-makers were younger and most were children of residents with dementia. (Table 2) Residents and surrogates in the intervention and control groups did not differ by age, gender, race, ethnicity, or religion. Residents had no difference in prognostic scores, weight loss or poor intake, but residents in the intervention sites were more likely to have chewing or swallowing problems at the time of enrollment (91% vs. 71%, p<0.001). Analyses were adjusted for this baseline difference. Prior to exposure to the decision aid, surrogates did not differ in knowledge, expectation of benefit, or decisional conflict scores.

Table 1.

Nursing Home Resident Characteristics by Intervention vs. Control Group

| Characteristic | Intervention (n=127) |

Control (n=129) |

p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 85.2 | 85.3 | 0.891 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 21% | 24% | 0.67 |

| Female | 79% | 76% | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Never Married | 7% | 5% | 0.74 |

| Married | 17% | 19% | |

| Widowed | 67% | 67% | |

| Separated | 0% | 1% | |

| Divorced | 9% | 9% | |

| Don’t Know | 1% | 0% | |

| Race | |||

| White | 67% | 73% | 0.73 |

| African American | 32% | 26% | |

| American Indian | 2% | 1% | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.6% | 0% | -- |

| Religion | |||

| Protestant | 83% | 71% | 0.20 |

| Catholic | 3% | 9% | |

| Jehovah’s Witness | 1% | 0% | |

| Jewish | 0% | 2% | |

| No Religion | 5% | 6% | |

| Other | 8% | 12% | |

| Don’t Know | 0% | 1% | |

| Difficulty with chewing/swallowing (% Yes) | 91% | 71% | <0.001 |

| Weight loss (% Yes) | 9% | 12% | 0.57 |

| Poor intake (% Yes) | 44% | 52% | 0.32 |

| MDS prognostic score (0–19) | 4.44 | 4.14 | 0.27 |

p values adjusted for nursing home intra-class correlation; MDS=Minimum Data Set

Table 2.

Surrogate Characteristics by Intervention Group

| Characteristic | Intervention (n=127) |

Control (n=129) |

p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.3 | 58.7 | 0.89 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 32% | 42% | 0.09 |

| Female | 68% | 58% | |

| Race | |||

| White | 67% | 73% | 0.57 |

| African American | 31% | 26% | |

| American Indian | 2% | 2% | |

| Other | 1% | 0% | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2.4% | 0% | -- |

| Religion | |||

| Protestant | 75% | 68% | 0.40 |

| Catholic | 4% | 6% | |

| Jehovah’s Witness | 3% | 2% | |

| Jewish | 1% | 2% | |

| No Religion | 7% | 5% | |

| Other | 10% | 17% | |

| How Religious | |||

| Very | 45% | 47% | 0.94 |

| Moderately | 41% | 37% | |

| Slightly | 10% | 13% | |

| Not religious | 3% | 3% | |

| Don’t Know | 0% | 1% | |

| Relationship | |||

| Spouse | 7% | 9% | 0.62 |

| Daughter | 48% | 43% | |

| Son | 20% | 29% | |

| Grandchildren | 5% | 4% | |

| Nephews & Nieces | 8% | 8% | |

| Siblings | 7% | 4% | |

| Other Family | 4% | 2% | |

| Non-Family | 2% | 2% | |

p values adjusted for nursing home intra-class correlation

Effect on Decisional Conflict

Although surrogates in both groups experienced the same level of decisional conflict at the time of study enrollment, after 3 months surrogates who received the decision aid had significantly lower scores on the Decisional Conflict Scale than surrogates receiving usual care (1.65 vs. 1.97, p<0.001), and lower scores on each subscale. (Table 3) Examining within-group change, both groups of surrogates experienced reduced decisional conflict over 3 months’ follow-up. However, those in the intervention arm had a significantly greater reduction (−0.60 vs. −0.13, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Effect of the Intervention on Quality of Decision-Making at 3 Months

| Intervention | Control |

p value* |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Decisional conflict (1–5)** | (n=118) | (n=115) | |

| Overall | 1.65 | 1.97 | <0.001 |

| Uncertainty | 1.88 | 2.15 | 0.01 |

| Effective decision making | 1.56 | 1.77 | 0.01 |

| Factors contributing to uncertainty | 1.61 | 2.00 | <0.001 |

| Decisional conflict change, 0–3 months** |

(n=118) −0.60 |

(n=115) −0.13 |

<0.001 |

| Overall | −0.97 | −0.42 | 0.005 |

| Uncertainty | −0.20 | 0.05 | 0.003 |

| Effective decision making | −0.66 | −0.12 | <0.001 |

| Factors contributing to uncertainty | |||

| Feeding discussions: (% Yes) | (n=126) | (n=127) | |

| Physician, nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant | 46% | 33% | 0.04 |

| Other nursing home staff | 64% | 71% | 0.42 |

| Satisfaction with decision-making (1–5) | 1.61 | 1.66 | 0.53 |

| Decisional regret (0–100) | 11.9 | 14.3 | 0.14 |

Means and percents are estimated from multiple linear regression or logistic regression models, adjusted for chewing/swallowing difficulties

p values adjusted for nursing home intra-class correlation

Measured for surviving nursing home residents only

Effect of the Intervention on Knowledge, Communication and Treatment Choices

After review of the decision aid intervention surrogates had higher mean knowledge scores than controls (16.8 vs 15.1, p<0.001), and expected fewer benefits from tube feeding (2.3 vs 2.6, p=0.001). Surrogates in both groups reported feeling somewhat or very involved in decisions about feeding treatments (83% vs 77%, p=0.18).

Over the next 3 months, surrogates in the intervention group were more likely than controls to have discussed feeding treatments with a physician, nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant (46% vs 33%, p=0.04). (Table 3) Although this pre-specified outcome focused on discussions with providers who write treatment orders, discussions with other nursing home staff were more common and did not differ between groups (64% vs 71%, p=0.42). Decisional regret was low, and satisfaction high at 3 months for both intervention and control surrogates.

After 3 months residents in the intervention group had increased use of some assisted oral feeding techniques compared with the control group. (Table 4) Residents in the intervention group were more likely to receive a dysphagia diet (89% vs 76%, p=0.04), and showed a trend toward increased use of specialized staff assistance for feeding (20% vs 10%, p=0.08). In secondary analyses, we found no differential effects of the intervention by surrogate race or religiosity.

Table 4.

Effect of the Intervention on Treatments

| 3 month outcomes | Intervention (n=127) |

Control (n=127) |

p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assisted feeding interventions | |||

| Any modified diet | 94% | 87% | 0.07 |

| Specialized dysphagia diet | 89% | 76% | 0.04 |

| High calorie supplement | 76% | 75% | 0.87 |

| Specialized staff assistance | 20% | 10% | 0.08 |

| Specialized utensils | 6% | 10% | 0.24 |

| Head / body positioning | 2% | 1% | 0.38 |

| 9 month outcomes | |||

| Number of new feeding tubes | 1 | 3 | 0.34 |

| Number of Do not Tube Feed orders | 4 | 2 | 0.41 |

| Chart records of discussions | 34 | 32 | 0.97 |

| Weight loss | 6% | 16% | 0.01 |

| Cumulative mortality rate | 27% | 29% | 0.69 |

Means and percents are estimated from multiple linear regression or logistic regression models, adjusted for baseline chewing/swallowing difficulties

p values adjusted for nursing home intra-class correlation

Since explicit choices for or against tube feeding were rare at 3 months, additional brief chart reviews were added to the protocol. Using cumulative data up to 9 months, 3 control residents and 1 intervention resident had a feeding tube (p=0.34), and 4 intervention and 2 control residents had orders not to tube feed (p=0.41). Weight loss was less common at 9 months for residents in the intervention group (6% vs 16%, p=0.01). No adverse effects of the intervention were identified, and mortality rates were similar for intervention and control residents at 3 months (6% vs 9%, p=0.58) and 9 months (27% vs 29%, p=0.69).

DISCUSSION

A decision aid about feeding options in advanced dementia was effective to improve the quality of decision-making by surrogates for nursing home residents with dementia. Building on a previously piloted decision aid, this is the first randomized trial with evidence of sustained benefit over time. Surrogates face the emotionally and ethically difficult role of deciding on care for seriously ill patients, and use of the decision aid resulted less conflict and greater knowledge of treatment options. They were also more likely to discuss treatments with a health care provider, indicating the decision aid supported rather than replaced clinical communication. Intervention residents were more often provided dysphagia diets, and experienced less weight loss.

Decision aids reduce decisional conflict and facilitate informed decision-making for a wide range of healthcare choices, but have rarely been tested in serious illness. Nearly all randomized trials address outpatient decisions such as use of hormone replacement, stroke prophylaxis, cancer screening, and elective surgery. 36,37 A few studies have tested decision aids for seriously ill patients and their families. Two trials found video decision aids on advance care planning increased geriatric or oncology outpatients’ interest in comfort care.26,38 In a 34-center randomized trial in France, an informational leaflet to augment communication with clinicians improved family comprehension of critical illness, although it did not target specific decisions.39 A decision aid about lung transplantation for adults with cystic fibrosis resulted in improved knowledge of risks and benefits and reduced decisional conflict at 3 weeks, with some evidence that choices remained durable up to a year.40

This study is the first trial of a decision aid conducted in the nursing home setting, and it provides evidence to improve the quality of surrogate decision-making despite the challenges to communication in this environment. One in four Americans, and 70% of people with dementia will spend their final days in a nursing home.41,42 Poor quality communication is a major practical barrier to improved care in advanced dementia.43 Families report limited contact with health professionals, and confusion about prognosis due to the prolonged trajectory of illness.44,45 Nursing home staff turnover rates are higher than in other healthcare settings.46,47 A majority of physicians do not provide nursing home care, and those who do are rarely on site.48 While the intervention increased frequency of communication, less than half of intervention surrogates discussed feeding options with a medical provider. Future decision aid interventions may be more effective if delivered while concurrently engaging medical providers, informing nursing home staff, or testing policy changes to promote time for communication.

The low rate of explicit decisions about tube feeding in both groups was an unexpected finding. Nursing homes in this study had overall rates of tube feeding (0–7%) consistent with state (6.92%) and national (5.97%) averages.28 In both groups, medical providers may have been responding to diffusion of evidence and a secular trend toward less tube feeding in dementia.49 Although the decision aid was not shared with clinicians in intervention nursing homes, they may have learned about decision aid content when discussing feeding options with surrogates.50 Clinicians in control sites were aware that their patients were enrolled in a trial addressing feeding options in dementia. Awareness of the study topic may have had a broader Hawthorne effect, causing clinicians to re-consider orders for tube feeding.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of study limitations. Cluster randomization prevented double-blinding, and may have introduced bias due to site effects. This approach was necessary to avoid unintended dissemination of the decision aid to controls, and it mimics adoption of decision aids in practice. Outcome measures were highly specified to reduce bias, and partial blinding was maintained by withholding information on outcomes from treating clinicians. Risk of bias was minimized by matching nursing homes on characteristics associated with tube feeding practices, and adjusting analyses for differences in baseline characteristics and for intra-class correlation. The study design did not evaluate nursing home clinicians’ knowledge or approach to decision-making. Providers are clustered within nursing homes, and individual clinicians’ practices could have enhanced or diluted the effect of the decision aid. Research sites were within a single state, which may limit generalizability of findings. Finally, the decision aid had statistically significant but clinically modest effects. This study design permits precise measurement of the effect of the decision aid alone, but effectiveness may be greater if combined with clinician education.

CONCLUSION

A decision aid about feeding options in advanced dementia improved the quality of decision-making for surrogates and their frequency of communication with medical providers. Use of decision aids in nursing homes is feasible and effective, and can improve informed treatment choices. Future decision aid interventions in nursing homes may be more effective if combined with provider engagement, changes in the roles of on-site professional staff, or systems interventions that facilitate face-to-face communication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding source: NIH-National Institute for Nursing Research R01 NR009826; Dr. Mitchell is supported by NIH-NIA K24AG033640.

Jan Busby-Whitehead, MD and Joanne Garrett, PhD for serving as Data Safety Monitors.

Sponsor’s Role: Funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

- Study concept and design: Hanson, Carey, Garrett, Ersek, Mitchell

- Acquisition of data: Hanson, Jackman, Gilliam, Wessell

- Analysis and interpretation of data: Hanson, Carey, Caprio, Lee, Ersek, Garrett, Mitchell

- Drafting and critical revision of the manuscript: Hanson, Carey, Caprio, Lee, Ersek, Garrett, Jackman, Gilliam, Wessell, Mitchell

- Statistical analysis: Garrett

- Obtained funding: Hanson, Carey

- Administrative, technical or material support: Hanson, Jackman, Gilliam, Wessell, Carey

- Study supervision: Hanson, Jackman

REFERENCES

- 1.Hebert LI, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, et al. Alzheimer’s disease in the US population: Prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larson EB, Shadlen MF, Wang L, et al. Survival after initial diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:501–509. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boustani M, Peterson CB, Hanson LC, et al. Screening for dementia syndrome: A review of the evidence. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:927–937. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-11-200306030-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, De Leon MJ, et al. The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf-Klein GP, Silverstone FA. Weight loss in Alzheimer’s disease: An international review of the literature. Int Psychogeriatr. 1994;6:135–142. doi: 10.1017/s1041610294001705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White H, Pieper C, Schmader K, et al. A longitudinal analysis of weight change in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:531–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volicer L, Seltzer B, Rheaume Y, et al. Eating difficulties in patients with probable dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Geriatr Psychol Neurol. 1989;2:188–195. doi: 10.1177/089198878900200404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Givens JL, Kiely DK, Carey K, et al. Health care proxies of nursing home residents with advanced dementia: decisions they confront and their satisfaction with decision-making. J Am Geriatr. 2009;57:1149–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez RP, Amella EJ. Time travel: The lived experience of providing feeding assistance to a family member with dementia. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2011;4:127–134. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20100729-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Kuo SK, et al. Decision-making and outcomes of feeding tube insertion: A five state study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:881–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, et al. Dying with dementia in long-term care. Gerontologist. 2008;48:741–751. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.6.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Lipsitz LA. The risk factors and impact on survival of feeding tubes in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meier DE, Aronheim JC, Morris J, et al. High short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with advanced dementia: Lack of benefit of tube feeding. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:594–599. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy LM, Lipman TO. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy does not prolong survival in patients with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1351–1353. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampson EL, Candy B, Jones L. Enteral tube feeding for older people with advanced dementia. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007209.pub2. http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab007209.html. Published Jan, 2009, viewed May 20, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Carey TS, Hanson LC, Garrett JM, et al. Expectations and outcomes of gastric feeding tubes. Am J Med. 2006;119:527.e11–527.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanson LC, Garrett JM, Lewis C, et al. Physicians’ expectations of benefit from tube feeding. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1130–1134. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brett AS, Rosenberg JC. The adequacy of informed consent for placement of gastrostomy tubes. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:745–748. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis CL, Hanson LC, Golin C, et al. Surrogates’ perceptions about feeding tube placement decisions. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. for the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. viewed 2/10/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, et al. Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: A systematic review. BMJ. 1999;319:731–734. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, et al. Effects of a decision aid on knowledge and treatment decision making for breast cancer surgery. JAMA. 2004;292:235–441. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pignone M, Harris R, Kinsinger L. Videotape-based decision aid for colon cancer screening: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:761–769. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-10-200011210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barry MJ. Health decision aids to facilitate shared decision making in office practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:127–135. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Barry MJ, et al. Video decision support tool for advance care planning in dementia: A randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338:b2159. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell SL, Tetroe J, O’Connor AM. A decision aid for long-term tube-feeding in cognitively impaired older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:313–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4930313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanson LC, Gilliam R, Lee TJ. Successful clinical trials research in nursing homes: The Improving Decision Making Study. Clinical Trials. 2010;7:735–743. doi: 10.1177/1740774510380241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS cognitive performance scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M174–M182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, De Leon MJ, et al. The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psych. 1982;139:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M174–M182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Connor AM. Validation of a Decisional Conflict Scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a decisional regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:281–292. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03256005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmes-Rovner M, Kroll J, Schmitt N, et al. Patient satisfaction with health care decisions: The Satisfaction with Decision Scale. Med Decis Making. 1996;16:58–64. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9601600114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB, et al. Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA. 2004;291:2734–2740. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Connor A, Bennett CL, Stacey D, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;8:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub2. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/o/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD001431/frame.html. Published July 8, 2009. Viewed December 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A, O’Connor AM, et al. A patient decision aid regarding antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:737–743. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.8.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Jawahri A, Podgurski LM, Eichner AF, et al. Use of video to facilitate end-of-life discussions with patients with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:305–310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Impact of a family information leaflet on effectiveness of information provided to family members of intensive care unit patients: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:438–442. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.200108-006oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vandemheen KL, O’Connor A, Bell SC, et al. Randomized trial of a decision aid for patients with cystic fibrosis considering lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:761–768. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0421OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, et al. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teno JM. [Accessed Nov 2, 2009];Facts on Dying. www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/factsondying.htm.

- 43.Birch D, Draper J. A critical literature review exploring the challenges of delivering effective palliative care to older people with dementia. J Clin Nursing. 2008:1144–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, et al. Dying with dementia in long-term care. Gerontologist. 2008;48:741–751. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.6.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Givens JL, Kiely DK, Carey K, et al. Healthcare proxies of nursing home residents with advanced dementia: Decisions they confront and their satisfaction with decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1149–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castle NG, Engberg J. Staff turnover and quality of care in nursing homes. Med Care. 2005;43:616–626. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163661.67170.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donoghue C, Castle N. Leadership styles of nursing home administrators and their association with staff turnover. Gerontologist. 2009;49:166–174. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levy C, Epstein A, Landry LA, et al. Physicians Practices in Nursing Homes: Final Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2006/phypracfr.htm. Viewed 12 / 04 / 09. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Braun UK, Rabeneck L, McCullough LB, et al. Decreasing use of percutanous endoscopic gastrostomy tube feeding for veterans with dementia – racial differences remain. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:242–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monteleoni C, Clark E. Using rapid-cycle quality improvement methodology to reduce feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia: Before and after study. BMJ. 2004;329:491–494. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7464.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]