Abstract

Background

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a life-threatening birth defect. Most of the genetic factors that contribute to the development of CDH remain unidentified.

Objective

Identify genomic alterations that contribute to the development of diaphragmatic defects.

Methods

A cohort of 45 unrelated patients with CDH or diaphragmatic eventrations were screened for genomic alterations by array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) or SNP-based copy number analysis.

Results

Genomic alterations that were likely to have contributed to the development of CDH were identified in eight patients. Inherited deletions of ZFPM2 were identified in two patients with isolated diaphragmatic defects and a large de novo 8q deletion overlapping the same gene was found in a patient with non-isolated CDH. A de novo microdeletion of chromosome 1q41q42 and two de novo microdeletions on chromosome 16p11.2 were identified in patients with non-isolated CDH. Duplications of distal 11q and proximal 13q were found in a patient with non-isolated CDH and a de novo single gene deletion of FZD2 was also identified in a patient with a partial pentalogy of Cantrell phenotype.

Conclusions

Haploinsufficiency of ZFPM2 can cause dominantly inherited isolated diaphragmatic defects with incomplete penetrance. Our data define a new minimal deleted region for CDH on 1q41q42, provide evidence for the existence of CDH-related genes on chromosomes 16p11.2, 11q23-24 and 13q12 and suggest a possible role for FZD2 and Wnt signaling in pentalogy of Cantrell phenotypes. These results demonstrate the clinical utility of screening for genomic alterations in individuals with both isolated and non-isolated diaphragmatic defects.

Keywords: Diaphragmatic hernia, ZFPM2, microdeletion 1q41q42, microdeletion 16p11.2, FZD2

INTRODUCTION

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a life-threatening birth defect that occurs in approximately 1/4000 live births and is defined as a protrusion of abdominal viscera into the thorax through an abnormal opening or defect in that is present at birth [1,2] In some cases the herniated viscera are covered by a membranous sac and can be difficult to distinguish from a diaphragmatic eventration in which there is extreme elevation of a part of the diaphragm that is often atrophic and abnormally thin. The majority of CDH cases are sporadic with the recurrence risk for isolated CDH typically quoted as <2% based on a multifactorial inheritance.[3] However, there is a growing body of evidence that small chromosomal anomalies can predispose to the development of CDH.[4–10]

The identification of a predisposing genomic change greatly enhances the ability of physicians to provide individualized genetic counseling and to formulate optimal treatment and surveillance plans. This would suggest that screening for genomic changes by array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) or SNP-based copy number analysis should be performed on all patients with diaphragmatic defects.[10,11] However, this practice has not been universally applied.

Efforts to map the locations of all reported chromosomal anomalies associated with CDH have revealed many regions of the genome that are recurrently deleted, duplicated or translocated in individuals with CDH.[12, 13] Each of these genomic regions is likely to harbor one or more CDH-related genes. For some of theses regions, a specific gene has been implicated in the development of diaphragmatic defects. Chromosome 8q22q23, for example, is recurrently deleted and translocated in individuals with CDH. This region harbors the zinc finger protein, multitype 2 (ZFPM2) gene that has been implicated in the development of diaphragmatic defects based the identification of a de novo truncating mutation in a child with a severe diaphragmatic eventration and the development of similar diaphragmatic defects in mice that are homozygous for a hypomorphic allele of Zfpm2.[14] In contrast, chromosome 1q41q42—which is also recurrently deleted in individuals with CDH—harbors a number of genes, none of which have been clearly shown to cause diaphragmatic defects in humans or animal models.[15]

In this report we screened a cohort of 45 individuals with diaphragmatic defects for genomic alterations by high-resolution aCGH or SNP-based copy number analysis. Chromosomal anomalies that are likely to have caused or contributed to the development of diaphragmatic defects were identified in eight patients. These findings allow us to define the inheritance pattern of diaphragmatic defects associated with haploinsufficiency of ZFPM2 and delineate a new minimal deleted region for CDH on 1q41q42. They also provide evidence for the existence of CDH-related genes on chromosomes 16p11.2, 11q23-24 and 13q12 and suggest a possible role for FZD2 and Wnt signaling in the development of various phenotypes seen in pentalogy of Cantrell.[16]

METHODOLOGY

Patient accrual

For array studies, informed consent was obtained from a convenience sample of 45 patients with CDH or diaphragmatic eventrations and, when possible, their parents in accordance with IRB-approved protocols. None of these patients have been previously published with the exception of Patient 5 and Patient 7 whose clinical findings were summarized by Shinawi et al. and Fruhman et al. respectively.[17,18]

For sequence analysis of ZFPM2, a cohort of 52 patients with CDH and 10 patients with diaphragmatic eventrations were screened for deleterious changes. This cohort consisted of a subset of patients from the array cohort and similarly consented individuals. ZFPM2 sequence analyses for these individuals have not been previously published.

Array comparative genomic hybridization and SNP-based copy number analyses

In most cases, chromosomal deletions and duplications were identified or confirmed by array comparative genomic hybridization on a research basis using Human Genome CGH 244K or SurePrint G3 Human CGH 1M Oligo MicroarrayKits (G4411B, G4447; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocols and analyzed as previously described using individual sex matched controls with no personal or family history of CDH.[7] Putative copy number changes were defined by twoor more adjacent probes at 244K resolution or three or more adjacent probes at 1M resolution with log2 ratios suggestive of a deletion or duplication when compared to those of adjacent probes.

In two cases—Patient 2 and Patient 6—causative chromosomal deletions were identified prior to accrual and further aCGH testing was unwarranted based on the molecular data already available. The deletion in Patient 2 was identified using an Illumina CytoSNP bead version 12.2 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and the deletion in Patient 6 was identified and defined on a clinical basis using a 105K Combimatrix Molecular Diagnostics array (Combimatrix Molecular Diagnostics, Irvine, CA, USA) hybridized, extracted, and evaluated according to manufacturers’ instructions.

Identification of previously reported copy number variants

To determine if putative changes identified by aCGH or SNP-based copy number analysis had been described previously in normal controls, we searched for similar deletions or duplications in the Database of Genomic Variants (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/).

Confirmation of Genomic Changes

Changes that were not identified in the Database of Genomic Variants were confirmed by real-time quantitative PCR with the exception of causative changes identified in Patients 3 and 7 which were confirmed by chromosome analysis and Patients 4 and 6 which were confirmed by FISH analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis experiments were designed and carried out as previously described.[7] For quantitative real-time PCR analysis within the ZFPM2 gene experiments were designed in a manner similar to the standard curve method described by Boehm et al. with a region of the c14orf145 gene serving as a control locus.[19]

Chromosome Analyses and FISH Studies

Chromosome analyses were performed for Patients 3 and 7 on a clinical basis by the Molecular Genetics Laboratory at Baylor College of Medicine. FISH analyses were performed for Patient 4 by the Cytogenetic Laboratory at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine and for Patient 6 by Combimatrix Molecular Diagnostics.

Long-range PCR amplification and sequencing

Long amplification PCR was carried out using the TaKaRa long range PCR system (TaKaRa Bio, Otsu, Shiga, Japan) according to manufacturer’s instructions. PCR products were gel-purified, sequenced, and analyzed using Sequencher 4.7 software (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA).

Identification of ZFPM2 sequence changes

Primers were designed to amplify the coding sequence and the intron-exon boundaries of ZFPM2 and used to amplify patient DNA. Sequence changes in PCR amplified products identified by comparison with control DNA sequences using Sequencher 4.7 software (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA).

Hispanic control samples were obtained from the Baylor Polymorphism Resource, a collection of approximately 600 anonymous control samples from major ethnic and racial backgrounds.

RESULTS

Identification of genomic changes in patients with CDH or diaphragmatic eventrations

Forty-five subjects with congenital diaphragmatic hernias or diaphragmatic eventrations of varying severity were screened for chromosomal anomalies by aCGH or SNP-based copy number analysis. Eight subjects carried genomic changes that likely contributed to the development of their diaphragmatic defects. Clinical and molecular data from these subjects are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of data from subjects with chromosomal changes likely to have contributed to diaphragm defects

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final Karyotype |

46,XY,del(8)(q2 2.3q23.1) |

46,XY,del(8)(q2 3.1q23.1) |

46,XX,del(8)(q2 2.3q24.23) |

46,XY,del(1)(q4 1q42.12) |

46,XY,del(16)(p 11.2p11.2) |

46,XY,del(16)(p 11.2p11.2) |

47,XX+der(13)t(11 ;13)(q23.2;q12.3) |

46,XY,del(17)(q 12.2-q12.2) |

| Minimal/maximal affected region (hg19) | Chromosome 8 deletion 105,914,640–106,907,764 (~993 kb)/105,880,441–106,922,626 (~1.04 Mb) | Chromosome 8 deletion 106,812,277–107,420,029 (~608 kb)/106,800,200–107,511,467 (~711 kb) | Chromosome 8 deletion 104,516,737–136,746,871 (~32.2 Mb)/104,508,082–136,809,150 (~32.3 Mb) | Chromosome 1 deletion 223,076,895–225,311,293 (2.2 Mb)/223,073,839–225,318,623 (2.2 Mb) | Chromosome 16 deletion 29,652,999–30,199,351 (~554 kb)/29,350,831–30,332,522 (~982 kb) | Chromosome 16 deletion 29,502,653–30,274,073 (~771 kb) defined clinically with no minimum or maximum region specified. | Chromosome 11 duplication 112,355,952–134,927,114 (26.6 Mb)/112,347,267–134,927,114 (26.6 Mb) Chromosome 13 duplication 19,296,527–32,250,725 (12.9 Mb)/19,168,012–32,271,202 (13.1 Mb) |

Chromosome 17 deletion 42,633,066–42,650,463 (~17.4 kb)/42,622,151–42,657,504 (~35.4 kb) |

| Confirmation Method | Real-time qPCR | Real-time qPCR | Chromosome analysis | FISH | Real-time qPCR | FISH | Chromosome analysis | Real-time qPCR |

| Inheritance | Paternal | Maternal | De novo | De novo | De novo | De novo | Maternal balanced translocation | De novo |

| Age | 4 year-old | 2 day-old | 1 day-old | 2 year-old | 2 year-old | 17 day-old | 8 day-old | 2 year-old |

| Gender | Male | Male | Female | Male | Male | Male | Female | Male |

| Ethnicity | Mixed | Caucasian | Hispanic | Caucasian | Mixed | Caucasian | Hispanic | Caucasian |

| Prenatally identified abnormalities, exposures, and prenatal karyotype | No abnormalities identified | CDH, intrauterine growth retardation, single umbilical artery, 46,XY | CDH, short extremities, edema/ascites, polyhydramnios, 46,XX,del(8)(q22q24) | No abnormalities identified on two prenatal ultrasounds | CDH, Maternal smoking in first trimester | CDH, normal chromosomes 46,XY | CDH, polyhydramnios and intrauterine growth retardation | CDH and omphalocele detected, normal chromosomes 46,XY |

| Birth history | Vaginal delivery at term, vomiting 2 days after birth | Caesarean section at 36 3/7 weeks for abnormal fetal heart rate and decreased movement | Spontaneous vaginal delivery at 34 5/7 wks | Spontaneous vaginal delivery at 37 weeks | Delivery at 37 weeks, after birth he decompensated and required 20 minutes of CPR | Repeat caesarean section at 39 6/7 weeks | Spontaneous vaginal delivery at 37 3/7 weeks | Scheduled caesarean section at 37 1/7 weeks |

| Birth weight, length and OFC | Weight 3.8 kg | Weight: 1.72 kg; length 42 cm; OFC 29.5 cm | No information available | Weight 3.2 kg; length 49.5 cm | Weight estimated at 2.5 kg; length 49 cm; OFC 34 cm. | Weight ~3.5 kg; length 50 cm; OFC 35.5 cm. | No information available | Weight 2.2 kg; length 45 cm, OFC 33 cm |

| Diaphragm | Diaphragmatic eventration | Left-sided CDH | Large left-sided CDH | CDH identified at 11 months | Right-sided CDH | Left-sided CDH | Large left-sided CDH | Anterior medial CDH |

| Cardiac | No known abnormalities | No known abnormalities | No known abnormalities | No known abnormalities | No structural abnormalities noted on ECHO | No structural abnormalities noted on ECHO | Small perimembranous VSD, secundum ASD | Large perimembranous VSD, PFO verses ASD |

| Additional anomalies | Intestinal malrotation, radioulnar synostosis | No known abnormalities | All extremities were symmetrically short with fixed flexion of the distal upper extremities | Right cerebral volume loss with ex vacuo dilatation of the right lateral ventricle, diffuse thin cortical mantle, atrophy of right hippocampus, this corpus callosum, left-sided cryptorchidism with non-attachment to the epididymis | Micro-retrognathia, cleft palate, right inguinal hernia and bilateral post axial polydactyly (paternal) | Hypoplastic, non-articulating thumbs, extra thoracic vertebra, 13 pairs of ribs | Clouded corneas, cupped optic nerves, cleft palate, small anterior anus, prominent forehead, large anterior fontanel posteriorly-rotated low-set ears, Micro-retrognathia wide-spaced hypoplastic nipples, right single palmar crease, tapering fingers, prominent heels. | Coronal craniosynostosis, diminished CNS white matter with thinning of the corpus callosum omphalocele, bilateral inguinal hernias, left-sided cryptorchidism. |

| Clinical course/development | Only two words at age two. Responded well to speech therapy. Now normal | Died on the 2nd day of life with respiratory insufficiency and pulmonary hypertension | Died shortly after delivery | Persistent hypoglycaemia after birth, gross motor, fine motor and language delay, seizures starting at 20 months | No oxygen requirement at 24 months but still receiving supplemental nutrition via g-tube | Died on the 17th day of life with severe respiratory insufficiency and pulmonary hypertension | Support was withdrawn at 8 days of age. Findings at autopsy included abnormal lung fissures and coronary artery anomalies | At 28 months could walk with a walker, nutritional support via g-tube, ventilator support with acute illness |

CDH = congenital diaphragmatic hernia, OFC = occipital frontal circumference, ASD = atrial septal defect, VSD = ventricular septal defect, ECHO = echocardiogram, CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation, CNS = central nervous system, PFO =patent foramen ovale.

Patient 1 is a male of mixed ancestry who was diagnosed at 9 days of age with intestinal malrotation and a large, left-sided diaphragmatic eventration (Figure 1). Later in life, he was diagnosed with left-sided radioulnar synostosis. Despite normal motor development, at 24 months of age he had only two words. However, he made rapid progress with speech therapy and by 31 months of age he was speaking in 4-word sentences.

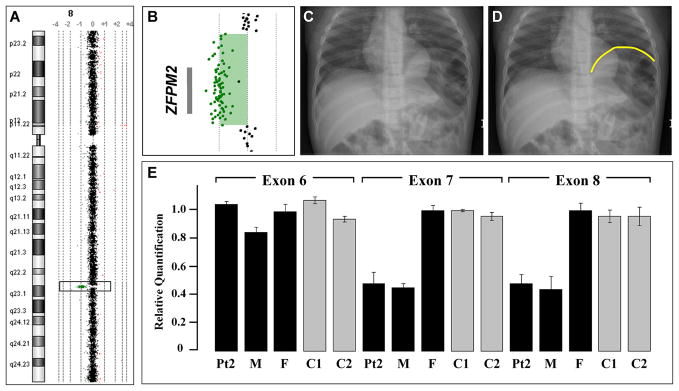

Figure 1.

A) Array comparative genomic hybridization data from Patient 1 showing an 8q22.3q23.1 single gene deletion of ZFPM2. B) The relative location of the ZFPM2 gene in relation to aCGH data from the deletion region in Patient 1 is represented by a gray bar. C) A chest radiograph of Patient 1 demonstrating a severe diaphragmatic eventration containing loops of bowel. D) The same radiograph shown in panel C with the limits of the diaphragmatic eventration outlined in yellow. E) Quantitative PCR analysis demonstrates a normal copy number for ZFPM2 Exon 6 but a reduced copy number for Exons 7 and 8 in DNA from Patient 2 (Pt2) and his mother (M). Normal copy number values are seen in DNA from Patient 2’s father (F) and DNA from two unrelated controls (C1, C2).

aCGH analysis revealed an ~1 Mb deletion that included only the ZFPM2 gene on chromosome 8q22.3-23.1 (Figure 1). Quantitative and long-range PCR analysis revealed that the patient’s father carried the same deletion (data not shown). A review of his father’s medical records did not reveal evidence of a diaphragmatic anomaly despite an extensive evaluation after a severe automobile accident which included an abdominal CT scan. We screened the coding sequence and associated intron exon boundaries of Patient 1’s remaining ZFPM2 allele looking for changes that might account for the difference in phenotype between him and his father but no sequence changes were identified.

Patient 2 is a Caucasian male that was diagnosed prenatally with a left-sided CDH. His brother was similarly affected with CDH and died of complications related to his hernia. Except for a single umbilical artery, no additional anomalies were identified after birth. He died at 2 day of age from respiratory insufficiency and pulmonary hypertension. SNP-based copy number analysis revealed a deletion on chromosome 8q23.1 that included a portion of the 3′ coding region of ZFPM2 and the first coding exon of oxidation resistance gene 1 (OXR1) based on mRNA transcript variant 1. Quantitative PCR analysis revealed that exons 7 and 8 of ZFPM2 were included in the deletion (Figure 1). No sequence changes were identified in the coding sequence and intron/exon boundaries of the remaining allele.

Patient 3 had a de novo ~32 Mb deletion from 8q22.3 to 8q24.23 that overlapped the ZFPM2 deletions seen in Patient 1 and 2 and also included the EXT1 and TRPS1 genes that are associated with Langer-Giedion syndrome (OMIM #150230). This Hispanic female was diagnosed prenatally with a large left-sided posterolateral CDH. Fetal MRI at 34 5/7 weeks also revealed an omphalocele and symmetrically short extremities. Due to severe pulmonary hypoplasia she was placed in neonatal hospice care immediately after birth and died shortly thereafter.

Patient 4 is a Caucasian male who had a normal prenatal course. He was born at 37 weeks gestation and his perinatal course was complicated by persistent hypoglycaemia. A diaphragmatic hernia was identified incidentally on a chest x-ray at 11 months of age during an investigation for failure to thrive. His motor and language development were delayed and he developed seizures at 20 months of age. CNS studies revealed right hemisphere cerebral volume loss with ex vacuo dilatation of the right lateral ventricle with diffuse thin cortical mantle, atrophy in the right hippocampus and a thin corpus callosum. aCGH analysis revealed a de novo 2.2 Mb interstitial deletion of 1q41–1q42.12 (Figure 2).

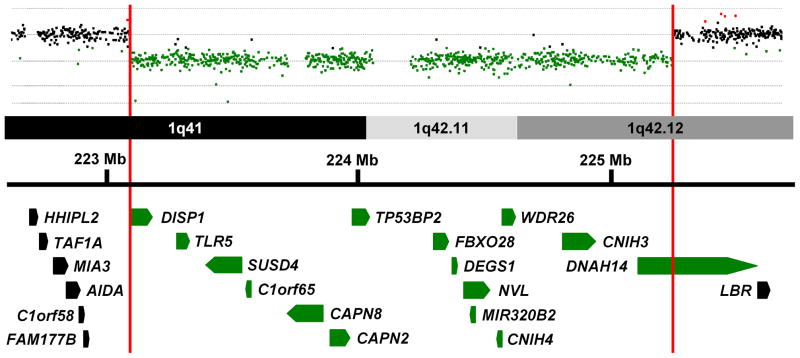

Figure 2.

Array comparative genomic hybridization data from Patient 4 is shown above a schematic representation of a portion of the 1q41–1q42 region. Genes in this region are represented by block arrows. Red vertical bars mark the limits of the deletion in Patient 4 and delineate the minimal deleted region for congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) in this region of the genome. Genes with all or a portion of their coding sequence inside the minimal deleted region are shown in green.

Patients 5 and Patient 6 were found to have de novo interstitial deletions of 16p11.2—a recurrent microdeletion region flanked by low-copy repeats. Patient 5 is a two-year old male of mixed ancestry who had a severe right-sided posterolateral CDH, micrognathia, a U-shaped palatal cleft, paternally inherited autosomal dominant polydactyly, and dysmorphic features consistent with 16p11.2 which were previously described.[17] He continues to need dietary supplementation via G-tube and supplemental oxygen when ill.

Patient 6 was a male infant conceived by intrauterine insemination with non-consanguineous Caucasian parents as donors. A left-sided diaphragmatic hernia was diagnosed prenatally. After birth, both of his thumbs were found to be proximally placed, hypoplastic and non-articulating with the left thumb having a pedunculated appearance. Additional findings included an extra thoracic vertebra and 13 pairs of ribs. He required extra corporal membrane oxygenation within the first day of life, developed severe diffuse edema, and died on the 17th day of life as a result of his severe respiratory insufficiency and pulmonary hypertension.

Patient 7 was born at 37 6/7 weeks to non-consanguineous Hispanic parents. She had persistent respiratory distress at birth and intubation was complicated by micrognathia and a tongue anomaly. Further evaluation revealed a left-sided CDH, a ventricular septal defect (VSD), and atrial septal defect (ASD), partial cleft palate, small anteriorly placed anus, and dysmorphic features. A marker chromosome was identified by G-banded chromosome analysis and was shown be the result of an unbalanced maternal translocation between chromosome 13q and 11q resulting in a 47,XX,+der(13)t(11;13)(q23;q12.3) chromosome complement.[18] Her prognosis was deemed poor in light of her multiple anomalies, and she died shortly after support was withdrawn on day of life 8. Additional findings at autopsy included abnormal lung fissures and coronary artery anomalies.

Patient 8 is a two-year old Caucasian male who was diagnosed prenatally with a left-sided anterior CDH, and a large omphalocele. Postnatal cardiac evaluation revealed a large perimembranous VSD and a patent foramen ovale (PFO) versus ASD. Additional anomalies included bilateral inguinal hernias, left-sided cryptorchism and premature fusion of the coronal sutures evident on head CT performed at 7 and 12 months of age. An MRI obtained at 11 months of age revealed diminished bifrontal and bitemporal parenchyma white matter associated with thinning of the corpus callosum, delayed myelination and generous extra-axial CSF spaces.

aCGH analysis revealed a de novo 17.4 kb deletion that involved only the frizzled homolog 2 gene (FZD2) on chromosome 17q12.2. Amplification of the breakpoint by long-range PCR followed by sequencing revealed that the deletion had occurred between two Alu repeats; an Alu-Sb proximally and an Alu-Sq distally. Matsuzaki et al. has reported deletions of this gene in 3/90 normal Yoruban individuals from Ibadan, Nigeria.[20] However, these changes were not identified by McCarroll et al. who analyzed the same cohort.[21]

To determine if the mutations in Patient 8’s remaining FZD2 allele may have contributed to his phenotype, we sequenced the coding region of his remaining FZD2 allele but did not identify any sequence changes.

Twenty changes not reported in the Database of Genomic Variants were identified in this cohort by aCGH and confirmed by either qPCR and/or FISH analysis (Table 2). In two cases the extent of the copy number variation was larger than that seen in the parents. Patient TX-28 appeared to have four copies of a region on 11q13.5 while her parents each had 3 copies compared to control. Patient TX-50 had no copies of a region on 17q25.1 while his parents each had one copy compared to control. TX-50 also had two copies of a region on Xp27.1, similar to his mother, which could represent a de novo event.

Table 2.

Rare inherited changes identified in patients with CDH

| Patient Number | Copy Number Change | Inheritance Pattern | Chromosome | Genes Involved | Minimum/Maximum hg19 | Clinical Synopsis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TX-02 | Increase | Paternal | 15q24.2 | COMMD4, NEIL1 | 75,605,889–75,644,263 75,600,108–75,648,132 |

Female, left-sided CDH, large bronchopulmonary sequestration |

| TX-04 | Increase | Paternal & maternal duplication | 3q26.33 | SOX2, SOX2OT | 181,430,003–181,431,902 181,425,656–181,432,270 |

Male, isolated right-sided CDH |

| Increase | Maternal | 5q11.2 | ARL15, HSPB3 | 53,450,417–53,759,016 53,443,541–53,765,448 |

||

| Increase | Paternal & maternal duplication | 18p11.21 | GNAL, MPPE1* | 11,872,270–11,878,083 11,863,962–11,884,082 |

||

| TX-12 | Decrease | Paternal | 7q32.1 | AHCYL2 | 128,988,273–128,996,545 128,978,921–129,002,744 |

Male, isolated left-sided CDH |

| TX-14 | Increase | Paternal | 13q21.33 | KLHL1, SCA8, ATXN8OS | 70,673,470–71,577,278 70,666,491–71,594,524 |

Male, isolated left-sided CDH |

| TX-23 | Increase | Maternal | 1p31.3 | CACHD1, RAVER2 | 65,144,120–65,210,203 65,137,345–65,218,480 |

Female, right-sided CDH, ASD, misshaped kidney |

| TX-27 | Decrease | Parents not available | 14q21.1 | FBXO33 | 39,884,781–40,262,115 39,875,206–40,301,762 |

Female, isolated left-sided |

| TX-28 | Increase | Patient n=4 Mother and Father n=3 | 11q13.5 | AQP11, CLNS1A, RSF1 | 77,297,657–77,424,591 77,270,540–77,431,584 |

Female, left-sided CDH, double outlet right ventricle, VSD |

| TX-36 | Decrease | Not maternal, father not available | 1p12 | HSD3B2 | 119,962,240–119,983,891 119,957,963–119,994,447 |

Male, isolated left-sided CDH |

| TX-39 | Decrease | Maternal | 16p13.3 | DNASE1, TRAP1 | 3,684,132–3,716,095 3,672,598–3,726,606 |

Female, left-sided posterior CDH, bicommissural aortic valve |

| TX-42 | Increase | Paternal & maternal Increased copy number | 1q24.3 | DNM3 | 171,944,462–171,958,347 171,936,289–171,970,634 |

Male, isolated left-sided posterior CDH |

| Decrease | Paternal | 15q21.2 | USP8*, USP50 | 50,802,672–50,822,065 50,791,758–50,833,347 |

||

| TX-50 | Decrease | Patient n=0 Parents n=1 | 17q25.1 | TRIM4* | 73,875,459–73,878,627 73,870,461–73,882,792 |

Male, isolated left-sided CDH |

| Increase | Maternal n=2 | Xq27.1 | F9, MCF2, ATP11C, MIR505, CXorf66 | 138,594,571–139,089,290 138,556,308–139,102,322 |

||

| TX-52 | Decrease | Paternal | 15q23 | AAGAB*, IQCH, C15orf61, MAP2K5 | 67,548,229–68,040,596 67,540,042–68,049,656 |

Female, right-sided CDH, ASD |

| TX-56 | Increase | Maternal | Xp11.1 | ZXDA | 57,704,902–57,987,522 57,673,005–58,051,706 |

Male, right-sided CDH, left-sided inguinal hernia |

| TX-65 | Decrease | Maternal | 7q31.1 | DOCK4 | 111,668,580–111,784,369 111,653,357–111,789,489 |

Male, left-sided CDH, extra-lobar pulmonary sequestration, |

| TX-72 | Increase | Paternal & maternal Increased copy number | 3q13.31 | GRAMD1C*, ZDHHC23 | 113,668,345–113,672,579 113,664,314–113,679,817 |

Male, left-sided posterior CDH, |

| TX-73 | Increase | Paternal | 20p12.2 | SNAP25, MKKS, C20orf94, JAG1 | 10,223,539–10,902,949 10,213,446–10,937,659 |

Male, left-sided CDH, ASD; sibling died shortly after birth with CDH |

genes located outside the minimal deleted region but are located, at least partially, inside the maximal deleted region; CDH = congenital diaphragmatic hernia, ASD = atrial septal defect, VSD = ventricular septal defect

Identifying ZFPM2 sequence changes in patients with CDH and diaphragmatic eventrations

To determine if detrimental sequence changes in ZFPM2 were a common cause of CDH or diaphragmatic eventrations, we screened the coding region and intron-exon boundaries of this gene in 52 patients with CDH (Table 3) and 10 patients with diaphragmatic eventrations (Table 4). Three non-synonymous changes were identified which had not been previously described in the 1000 Genomes project or dbSNP. A D98N change was identified in a male with an isolated posterior left-sided hernia with a large sac. His mother did not carry a D98N allele but the father was unavailable for analysis. This change was predicted to be possibly damaging by PolyPhen (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/) but non-deleterious by SNPs3D (http://www.snps3d.org/).[22, 23] The same change was reported by Bleyl et al. in an individual with bilateral CDH.[24] However, they concluded that the change was likely to be a benign SNP since it was also identified in control samples.

Table 3.

ZFPM2 sequence changes in patients with CDH

| Observed change | Number of Patients (Inheritance Pattern) | Exon | 1000 Genomes*/dbSNP (Heterozygosity) | Predicted effect (PolyPhen/SNPs3D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-synonymous changes | ||||

| D98N | 1 (Non-maternal, father not available) | 3 | No/No | Possibly damaging/Non-Deleterious |

| S210T | 1 (Paternal) | 6 | No/No | Benign/Non-Deleterious |

| A403G | 11 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.341) | Benign/Non-Deleterious |

| E782D | 10 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.078) | Benign/Non-Deleterious |

| Q889E | 1 (Non-maternal father not available) | 8 | No/No—3.3% Hispanic control chromosomes | Benign/Non-Deleterious |

| A1055V | 1 (Non-maternal, father not available) | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.146) | Benign/Non-Deleterious |

| Synonymous changes | ||||

| P454P | 4 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.234) | -- |

| P592P | 3 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.101) | -- |

| V795V | 2 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.120) | -- |

| Y992Y | 3 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.104) | -- |

| H1069H | 4 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.234) | -- |

| L1123L | 3 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.156) | -- |

Data accessed on 3/8/2011

Table 4.

ZFPM2 sequence changes in patients with diaphragmatic eventrations

| Observed change | Number of Patients | Exon | 1000 Genomes*/dbSNP (Heterozygosity) | Predicted effect (PolyPhen) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-synonymous changes | ||||

| A403G | 1 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.341) | Benign/Non-Deleterious |

| E782D | 2 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.078) | Benign/Non-Deleterious |

| Synonymous changes | ||||

| P454P | 1 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.234) | -- |

| P592P | 1 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.101) | -- |

| V795V | 2** | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.120) | -- |

| H1069H | 1 | 8 | Yes/Yes (0.234) | -- |

Data accessed on 3/8/2011

Homozygous in one of the patients

A Q889E change was identified in a Hispanic female with a right-sided CDH, ambiguous genetalia and a double vagina. Her mother did not carry the change but the father was unavailable for analysis. This change was predicted to be benign by PolyPhen, non-deleterious by SNPs3D, and was subsequently identified in 5 of 152 (3.3%) Hispanic control chromosomes.

A paternally inherited S210T mutation in an African American male with a left-sided CDH and dysmorphic features. This change was predicted to be benign by PolyPhen and non-deleterious by SNPs3D.

DISCUSSION

aCGH and SNP-based copy number analyses are commonly used as a primary screening tool to identify genomic aetiologies in patients with congenital anomalies. Identification of these changes can provide information that physicians can use to hone the prognostic and recurrence risk information given to families and to create individualized therapeutic and surveillance plans for patients.

Haploinsufficiency of ZFPM2 causes autosomal dominant isolated diaphragmatic defects with incomplete penetrance

ZFPM2 is a transcriptional co-factor that forms heterodimers with GATA transcription factors to regulate gene expression during development.[25] The role of ZFPM2 in development of diaphragmatic defects was first demonstrated by Ackerman et al. who showed that mice homozygous for a hypomorphic mutation in Zfpm2 develop diaphragmatic eventrations.[14] In the same publication, they reported a de novo heterozygous R112X mutation in an infant with severe diaphragmatic eventrations and pulmonary hypoplasia who died shortly after birth.[14]

Patient 1 is the second child in which haploinsufficiency for ZFPM2 has been seen in association with a severe diaphragmatic eventration. Although Patient 2’s deletion affects both the 3′ end of ZFPM2 and the first coding exon of OXR1, it is likely that disruption of ZFPM2 underlies the development of CDH in this patient since OXR1 appears to be involved in the prevention of oxidative damage—a process that has not been implicated in the development of diaphragmatic defects.[26] Although DNA is not available on Patient 2’s brother, it is likely that he inherited the same deletion from his mother which contributed to his CDH. Alterations in ZFPM2 activity may also be the major, if not the sole, genetic factor that contributed to the development of CDH in Patient 3 and previously reported individuals with CDH with deletions and translocation involving 8q22q23 (Supplemental Table 2).[13] Since both Patient 1 and Patient 2 inherited their deletions from unaffected parents we conclude that loss-of-function alleles of ZFPM2 are associated with autosomal dominant diaphragmatic defects—CDH or diaphragmatic eventrations—with incomplete penetrance.

The identification of the causative genomic changes in Patient 1 and 2, both of whom had only minor anomalies—radioulnar synostosis diagnosed at 2 and half years of age and a single umbilical artery, respectively—provide further evidence that such studies should be considered in individuals who appear to have isolated diaphragmatic defects.

Alterations in ZFPM2 underlie a small fraction of congenital diaphragmatic defects

Screening of the ZFPM2 gene in 52 patients with CDH and 10 patients with diaphragmatic eventrations failed to identify any clearly deleterious changes in the ZFPM2 gene. Similarly, Ackerman et al. did not find deleterious ZFPM2 sequence changes in 29 additional post mortem samples from children with diaphragmatic defects.[14] However, Bleyl et al., screened 96 CDH patients—53 with isolated CDH, 36 with CDH and additional anomalies, and 7 with CDH and known chromosomal anomalies—and identified a rare amino acid change, M703L, in a patient with isolated CDH that is predicted to be possibly damaging by PolyPhen and deleterious by SNPs3D (Supplemental Table 3).[24] These data suggests that severe, deleterious alterations in ZFPM2 account for only a small portion of diaphragmatic defects. It is unclear, however, whether individual changes, like M703L, increase the risk for CDH and, if so, to what degree.

Delineation of new minimal deleted region for CDH on 1q41q42

Chromosome 1q41q42 has been shown to be recurrently deleted in individuals with CDH. The 1q41q42 minimal deleted region for CDH was previously defined by the maximal region of overlap between a patient reported by Kantarci et al. and a patient described by Van Hove et al. who were subsequently referred to as Patient 7 and Patient 4, respectively, by Shaffer et al.[6, 15, 27] This interval spanned ~6.3 Mb (220,120,384–226,397,002 hg19) and contained 48 RefSeq genes.

The maximal proximal and distal breakpoints of our Patient 4’s deletion are located inside the CDH region defined by Shaffer et al.[15] These breakpoints can be used to define a new minimal deleted region for CDH on chromosome 1q41q42 which spans ~2.2 Mb (223,073,839–225,318,623 hg19) and contains only 15 RefSeq genes (Figure 2).

This refined minimal deleted region for CDH does not contain the H2.0-like homeobox (HLX) gene which has been considered a candidate gene for CDH based on its expression in the murine diaphragm and the diaphragmatic defects identified in Hlx−/− mice.[28–30]. Although it is possible that haploinsufficiency of HLX can contribute to the formation of diaphragmatic defects in humans, its exclusion from the minimal deleted region for CDH suggests that alterations in HLX function are not required for the development of CDH in association with 1q41q42 deletions.

The dispatched homolog 1 (DISP1) gene has also been considered a candidate gene for CDH and is located within the new minimal deleted interval for CDH. DISP1 is a membrane spanning protein that plays an essential role in SHH signaling.[31] The potential role of DISP1 in the formation of CDH is supported by evidence that murine Disp1 is expressed in the pleuroperitoneal fold (PPF), a structure that is often considered to be the primordial mouse diaphragm and the identification of a somatic Ala1471Gly mutation—predicted to be benign by PolyPhen but “not tolerated” by SIFT (http://blocks.fhcrc.org/sift/SIFT.html)—in a patient with CDH and other anomalies.[32] However, abnormalities in other SHH signaling proteins have yet to be clearly shown to cause CDH. Truncating mutations (W475X and Y734X) in DISP1 have been found in two individuals with microforms of holoprosencephaly and their unaffected mothers—consistent with DISP1’s role in SHH signaling—but not in individuals with diaphragmatic defects.[32, 33] This suggests that consideration should be given to the possible role of other 1q41q42 genes in the development of CDH. The tumor protein p53 binding protein, 2 (TP53BP2) gene could play a role in CDH development by modulating apoptosis and cell proliferation through interactions with other regulatory molecules and has been shown to play a critical role in heart and CNS development in mice.[34, 35] The WD repeat domain 26 (WDR26) gene is another candidate gene that is widely expressed and could play a role in the development of CDH by regulating cell signaling pathways and modulating cell proliferation.[36, 37]

CDH is recurrently seen in 16p11.2 microdeletion syndrome

Recurrent 16p11.2 microdeletions result in a constellation of defects including developmental delay, cognitive impairment, behavioral problems, seizures and congenital anomalies.[17] Both Patient 5 and Patient 6 have de novo deletions of this region suggesting that CDH should be added to the list of congenital anomalies associated with this microdeletion syndrome.

The T-box 6 gene (TBX6) is located on 16p11.2 and encodes a transcription factor that has been shown to play a critical role in important developmental processes including paraxial mesoderm differentiation and left right patterning.[38, 39] As a result, TBX6 has been hypothesized to contribute to many of the congenital anomalies associated with 16p11.2.[17] It is possible that haploinsufficiency of TBX6 also contribute to the development of CDH.

Evidence of CDH-related genes on distal chromosome 11q and proximal chromosome 13q

Patient 7 carried an extra derivative 13 chromosome making her trisomic for a portion of the chromosome 13 extending to 13q12.3 and a portion of chromosome 11 extending from 11q23 to the telomere—47,XX,+der(13)t(11;13)(q23.2;q12.3). A similar chromosomal complement 47,XY,+der(13)t(11;13)(q21;q14) was seen in a boy with CDH described by Park et al. suggesting that upregulation of genes on distal 11q and/or proximal 13q may play a role in the development of CDH.[40] In support of this hypothesis, duplications of 11q have been recurrently seen in patients with CDH with many cases being associated with an unbalanced 3:1 meiotic segregation of the common t(11;22) translocation—resulting in a 47,XX or XY,+der(22)t(11;22)(q23.3;q11.2) chromosomal complement.[13, 41] Multiple cases of CDH associated with trisomy 13 have also been described providing support for the existence of one or more CDH-related genes on chromosome 13.[13]

The role of FZD2 and Wnt signaling in the development of CDH and defects associated with pentalogy of Cantrell

The cardiac, diaphragmatic and anterior wall defects seen in Patient 8, are similar to those described in pentalogy of Cantrell—a constellation of defects described by Cantrell et al. that includes, a supraumbilical omphalocele, a lower sternal cleft, a defect in the central tendon of the diaphragm, a defect in the pericardium, and an intracardiac anomaly.[16] A de novo deletion of FZD2 was identified in Patient 8 but similar deletions have been reported in normal individuals from Ibadan, Nigeria.[20] Although this suggests that haploinsufficiency of FZD2 is unlikely to be the sole cause of this patient’s phenotype, several lines of evidence suggest that decreased FZD2 expression may have contributed to this child’s phenotype.

Frizzled genes encode a family of seven transmembrane domain proteins that act as receptors for Wnt signaling proteins.[42] FZD2 is expressed in a variety of organs during development (Supplemental Table 1) and its protein product has been shown to interact with WNT3A and WNT5A and to signal through both the canonical (Wnt/beta-catenin) and non-canonical (Wnt/Ca++ and cyclic GMP) Wnt pathways.[43] In chick embryos, Wnt3a and Wnt5a modulate the migration of mesodermal precursors and Wnt3a has been shown to control the movement patterns of cardiac progenitor cells.[44, 45] Wnt signaling has also been shown to play a role in the development of CDH and omphalocele in humans. X-linked dominant mutations in PORCN, a gene that encodes a protein that modifies Wnt proteins—including WNT3A—for membrane targeting and secretion, have been shown to cause CDH and omphalocele as part of focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome; OMIM #305600).[46, 47]

It is possible that deletion of FZD2, in combination with other genetic and/or environmental factors, caused dysregulation of these Wnt signaling pathways, leading to the development of the cardiac defects, CDH and omphalocele seen in Patient 8. The potential role of frizzled signaling in developmental processes that require directional tissue movements followed by tissue fusion is supported by the work of Yu et al. who recently showed that mouse frizzled 1 (Fzd1) and frizzled 2 (Fzd2) genes play an essential and partially redundant role in the correct positioning of the cardiac outflow tract and closure of the palate and ventricular septum.[48] Genetic changes that disrupt these processes may ultimately be found to contribute to other cases of partial or complete pentalogy of Cantrell.

Genomic changes of unknown significance

The majority of the rare genomic changes catalogued in Table 2 are not located within genomic regions that have been shown to be recurrently deleted or duplicated in individuals with CDH and do not affect genes/pathways that have been clearly implicated in the development of diaphragmatic defects. Although the significance of these changes is presently unknown, it is likely that future studies, in humans and animal models, will help to clarify whether these changes increase the risk of developing diaphragm defects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the families who participated in this study. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Brendan Lee who served as a scientific mentor and provided and cared for study patients and Dr. John W. Belmont who provided and cared for study patients.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants T32-GM007330-33S1 and F30-HL099469-01 (MJW), and KO8-HD050583 and R01-HD065667 (DAS). DV was supported by a Sophia-Erasmus MC grant SSWO 551. This work was also supported by Award Number P30HD024064 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. These funding sources had no direct involvement in the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of this report and the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

LICENCE FOR PUBLICATION

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non-exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Group and co-owners or contracting owning societies (where published by the BMJ Group on their behalf), and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in the Journal of Medical Genetics and any other BMJ Group products and to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence.

COMPETING INTEREST

None declared.

References

- 1.Stege G, Fenton A, Jaffray B. Nihilism in the 1990s: the true mortality of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics. 2003;112:532–535. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pober BR. Overview of epidemiology, genetics, birth defects, and chromosome abnormalities associated with CDH. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2007;145C:158–171. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards JH. The simulation of mendelism. Acta Genet Stat Med. 1960;10:63–70. doi: 10.1159/000151119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klaassens M, van Dooren M, Eussen HJ, Douben H, den Dekker AT, Lee C, Donahoe PK, Galjaard RJ, Goemaere N, de Krijger RR, Wouters C, Wauters J, Oostra BA, Tibboel D, de Klein A. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia and chromosome 15q26: determination of a candidate region by use of fluorescent in situ hybridization and array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:877–882. doi: 10.1086/429842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slavotinek A, Lee SS, Davis R, Shrit A, Leppig KA, Rhim J, Jasnosz K, Albertson D, Pinkel D. Fryns syndrome phenotype caused by chromosome microdeletions at 15q26.2 and 8p23.1. J Med Genet. 2005;42:730–736. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantarci S, Casavant D, Prada C, Russell M, Byrne J, Haug LW, Jennings R, Manning S, Blaise F, Boyd TK, Fryns JP, Holmes LB, Donahoe PK, Lee C, Kimonis V, Pober BR. Findings from aCGH in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH): a possible locus for Fryns syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:17–23. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott DA, Klaassens M, Holder AM, Lally KP, Fernandes CJ, Galjaard RJ, Tibboel D, de Klein A, Lee B. Genome-wide oligonucleotide-based array comparative genome hybridization analysis of non-isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:424–430. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Esch H, Backx L, Pijkels E, Fryns JP. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia is part of the new 15q24 microdeletion syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52:153–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wat MJ, Enciso VB, Wiszniewski W, Resnick T, Bader P, Roeder ER, Freedenberg D, Brown C, Stankiewicz P, Cheung SW, Scott DA. Recurrent microdeletions of 15q25.2 are associated with increased risk of congenital diaphragmatic hernia, cognitive deficits and possibly Diamond--Blackfan anaemia. J Med Genet. 2010;47:777–781. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.075903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srisupundit K, Brady PD, Devriendt K, Fryns JP, Cruz-Martinez R, Gratacos E, Deprest JA, Vermeesch JR. Targeted array comparative genomic hybridisation (array CGH) identifies genomic imbalances associated with isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) Prenat Diagn. 2010;30:1198–1206. doi: 10.1002/pd.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott DA. Genetics of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16:88–93. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lurie IW. Where to look for the genes related to diaphragmatic hernia? Genetic Counseling. 2003;14:75–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holder AM, Klaassens M, Tibboel D, de Klein A, Lee B, Scott DA. Genetic factors in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:825–845. doi: 10.1086/513442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ackerman KG, Herron BJ, Vargas SO, Huang H, Tevosian SG, Kochilas L, Rao C, Pober BR, Babiuk RP, Epstein JA, Greer JJ, Beier DR. Fog2 is required for normal diaphragm and lung development in mice and humans. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:58–65. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaffer LG, Theisen A, Bejjani BA, Ballif BC, Aylsworth AS, Lim C, McDonald M, Ellison JW, Kostiner D, Saitta S, Shaikh T. The discovery of microdeletion syndromes in the post-genomic era: review of the methodology and characterization of a new 1q41q42 microdeletion syndrome. Genet Med. 2007;9:607–616. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e3181484b49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cantrell JR, Haller JA, Ravitch MM. A syndrome of congenital defects involving the abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, and heart. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1958;107:602–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinawi M, Liu P, Kang SH, Shen J, Belmont JW, Scott DA, Probst FJ, Craigen WJ, Graham BH, Pursley A, Clark G, Lee J, Proud M, Stocco A, Rodriguez DL, Kozel BA, Sparagana S, Roeder ER, McGrew SG, Kurczynski TW, Allison LJ, Amato S, Savage S, Patel A, Stankiewicz P, Beaudet AL, Cheung SW, Lupski JR. Recurrent reciprocal 16p11.2 rearrangements associated with global developmental delay, behavioural problems, dysmorphism, epilepsy, and abnormal head size. J Med Genet. 2010;47:332–341. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.073015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fruhman G, El-Hattab AW, Belmont JW, Patel A, Cheung SW, Sutton VR. Suspected trisomy 22: Modification, clarification, or confirmation of the diagnosis by aCGH. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155:434–438. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boehm D, Herold S, Kuechler A, Liehr T, Laccone F. Rapid detection of subtelomeric deletion/duplication by novel real-time quantitative PCR using SYBR-green dye. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:368–378. doi: 10.1002/humu.20011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuzaki H, Wang PH, Hu J, Rava R, Fu GK. High resolution discovery and confirmation of copy number variants in 90 Yoruba Nigerians. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R125. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-11-r125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarroll SA, Kuruvilla FG, Korn JM, Cawley S, Nemesh J, Wysoker A, Shapero MH, de Bakker PI, Maller JB, Kirby A, Elliott AL, Parkin M, Hubbell E, Webster T, Mei R, Veitch J, Collins PJ, Handsaker R, Lincoln S, Nizzari M, Blume J, Jones KW, Rava R, Daly MJ, Gabriel SB, Altshuler D. Integrated detection and population-genetic analysis of SNPs and copy number variation. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ng.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sunyaev S, Ramensky V, Koch I, Lathe W, 3rd, Kondrashov AS, Bork P. Prediction of deleterious human alleles. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:591–597. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yue P, Melamud E, Moult J. SNPs3D: candidate gene and SNP selection for association studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bleyl SB, Moshrefi A, Shaw GM, Saijoh Y, Schoenwolf GC, Pennacchio LA, Slavotinek AM. Candidate genes for congenital diaphragmatic hernia from animal models: sequencing of FOG2 and PDGFRalpha reveals rare variants in diaphragmatic hernia patients. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:950–958. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantor AB, Orkin SH. Coregulation of GATA factors by the Friend of GATA (FOG) family of multitype zinc nger proteins. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volkert MR, Elliott NA, Housman DE. Functional genomics reveals a family of eukaryotic oxidation protection genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14530–14535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260495897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Hove JL, Spiridigliozzi GA, Heinz R, McConkie-Rosell A, Iafolla AK, Kahler SG. Fryns syndrome survivors and neurologic outcome. Am J Med Genet. 1995;59:334–340. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320590311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lints TJ, Hartley L, Parsons LM, Harvey RP. Mesoderm-specific expression of the divergent homeobox gene HLX1 during murine embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 1996;205:457–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199604)205:4<457::AID-AJA9>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hentsch B, Lyons I, Li R, Hartley L, Lints TJ, Adams JM, Harvey RP. Hlx homeo box gene is essential for an inductive tissue interaction that drives expansion of embryonic liver and gut. Genes Dev. 1996;10:70–79. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slavotinek AM, Moshrefi A, Lopez Jiminez N, Chao R, Mendell A, Shaw GM, Pennacchio LA, Bates MD. Sequence variants in the HLX gene at chromosome 1q41–1q42 in patients with diaphragmatic hernia. Clin Genet. 2009;75:429–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma Y, Erkner A, Gong R, Yao S, Taipale J, Basler K, Beachy PA. Hedgehog-mediated patterning of the mammalian embryo requires transporter-like function of dispatched. Cell. 2002;111:63–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00977-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kantarci S, Ackerman KG, Russell MK, Longoni M, Sougnez C, Noonan KM, Hatchwell E, Zhang X, Pieretti Vanmarcke R, Anyane-Yeboa K, Dickman P, Wilson J, Donahoe PK, Pober BR. Characterization of the chromosome 1q41q42.12 region, and the candidate gene DISP1, in patients with CDH. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2493–2504. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roessler E, Ma Y, Ouspenskaia MV, Lacbawan F, Bendavid C, Dubourg C, Beachy PA, Muenke M. Truncating loss-of-function mutations of DISP1 contribute to holoprosencephaly-like microform features in humans. Hum Genet. 2009;125(4):393–400. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0628-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Liu W, Naumovski L, Neve RL. ASPP2 inhibits APP-BP1-mediated NEDD8 conjugation to cullin-1 and decreases APP-BP1-induced cell proliferation and neuronal apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2003;85:801–809. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vives V, Su J, Zhong S, Ratnayaka I, Slee E, Goldin R, Lu X. ASPP2 is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor that cooperates with p53 to suppress tumor growth. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1262–1267. doi: 10.1101/gad.374006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu Y, Wang Y, Xia C, Li D, Li Y, Zeng W, Yuan W, Liu H, Zhu C, Wu X, Liu M. WDR26: a novel Gbeta-like protein, suppresses MAPK signaling pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2004;93:579–587. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei X, Song L, Jiang L, Wang G, Luo X, Zhang B, Xiao X. Overexpression of MIP2, a novel WD-repeat protein, promotes proliferation of H9c2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393:860–863. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE. Three neural tubes in mouse embryos with mutations in the T-box gene Tbx6. Nature. 1998;391:695–697. doi: 10.1038/35624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hadjantonakis AK, Pisano E, Papaioannou VE. Tbx6 regulates left/right patterning in mouse embryos through effects on nodal cilia and perinodal signaling. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park JP, McDermet MK, Doody AM, Marin-Padilla JM, Moeschler JB, Wurster-Hill DH. Familial t(11;13) (q21;q14) and the duplication 11q,13q phenotype. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:46–48. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320450113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klaassens M, Scott DA, van Dooren M, Hochstenbach R, Eussen HJ, Cai WW, Galjaard RJ, Wouters C, Poot M, Laudy J, Lee B, Tibboel D, de Klein A. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with duplication of 11q23-qter. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1580–1586. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang HY, Liu T, Malbon CC. Structure-function analysis of Frizzleds. Cell Signal. 2006;18:934–941. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sato A, Yamamoto H, Sakane H, Koyama H, Kikuchi A. Wnt5a regulates distinct signalling pathways by binding to Frizzled2. EMBO J. 2010;29:41–54. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sweetman D, Wagstaff L, Cooper O, Weijer C, Münsterberg A. The migration of paraxial and lateral plate mesoderm cells emerging from the late primitive streak is controlled by different Wnt signals. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yue Q, Wagstaff L, Yang X, Weijer C, Münsterberg A. Wnt3a-mediated chemorepulsion controls movement patterns of cardiac progenitors and requires RhoA function. Development. 2008;135:1029–1037. doi: 10.1242/dev.015321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Reid Sutton V, Omar Peraza-Llanes J, Yu Z, Rosetta R, Kou YC, Eble TN, Patel A, Thaller C, Fang P, Van den Veyver IB. Mutations in X-linked PORCN, a putative regulator of Wnt signaling, cause focal dermal hypoplasia. Nat Genet. 2007;39:836–838. doi: 10.1038/ng2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dias C, Basto J, Pinho O, Barbêdo C, Mártins M, Bornholdt D, Fortuna A, Grzeschik KH, Lima M. A nonsense PORCN mutation in severe focal dermal hypoplasia with natal teeth. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2010;29:305–313. doi: 10.3109/15513811003796912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu H, Smallwood PM, Wang Y, Vidaltamayo R, Reed R, Nathans J. Frizzled 1 and frizzled 2 genes function in palate, ventricular septum and neural tube closure: general implications for tissue fusion processes. Development. 2010;137:3707–3717. doi: 10.1242/dev.052001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.