Abstract

Infecting rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) with the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) is an established animal model of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pathogenesis. Many studies have used various derivatives of the SIVmac251 viral swarm to investigate several aspects of the disease, including transmission, progression, response to vaccination, and SIV/HIV-associated neurological disorders. However, the lack of standardization of the infecting inoculum complicates comparative analyses. We investigated the genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships of the 1991 animal-titered SIVmac251 swarm, the peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) passaged SIVmac251, and additional SIVmac251 sequences derived over the past 20 years. Significant sequence divergence and diversity were evident among the different viral sources. This finding highlights the importance of characterizing the exact source and genetic makeup of the infecting inoculum to achieve controlled experimental conditions and enable meaningful comparisons across studies.

Experimental infection of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) provides a powerful platform for studying the pathogenesis of AIDS-related neurological disorders and for the development of effective vaccines.1–3 The natural course of infection in the SIV/macaque model is similar to that of non-antiretroviral-treated HIV-1 patients.1 For example, SIV-infected monkeys often have chronic diarrhea and large decreases in body weight at the time of death. The absolute number of CD4+ lymphocytes, as well as CD4:CD8 ratio, decreases in the peripheral circulation during the infection.4 Additionally, many of the macaques develop a viral-induced meningoencephalitis.1

SIVmac251 and SIVsmE660 are the most common pathogenic viral swarms used as inoculum in experimental animal models. This study concentrates on the SIVmac251 viral swarm, which was initially derived from rhesus macaque Mm251-79 infected by inoculation of minced spontaneous lymphoma tissue, and subsequently amplified in monkey-derived cells.5 This stock is considered the “original 1991 viral swarm (SIVmac251_1991).” Since that time, different SIVmac251 stocks were obtained. Many resulted by passaging in vitro the original SIVmac251_1991 or by isolating a new swarm from animals infected with the 1991 quasispecies. Other SIVmac251 swarms were passaged in parallel to the SIVmac251_1991 quasispecies (R. Desrosiers, personal communication). However, with a few exceptions,6–8 the origin and culture condition of the stock being used as the inoculum in each specific experimental setting are frequently unclear from publications.

The lack of in-depth characterization of these differently derived SIVmac251 swarms, and their potential variability, may introduce a confounding factor in the interpretation and comparison of results across studies. For example, the use of more virulent swarms may underestimate the potential protective efficacy of some immunization strategies.9,10 Additionally, inocula with diverse genetic heterogeneity may lead to different outcomes during acute infection due to the number of transmitted variants and/or the presence of viral strains with specific phenotypes (e.g., cellular tropism). Therefore, the objective of the present study was to compare the diversity and analyze the phylogenetic relationships of the different SIVmac251 viral swarms.

Table 1 shows an overview of the viral sequences analyzed. The SIVmac251_2006 swarm was derived by expanding an aliquot of the 1991 quasispecies in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from superclean-specific pathogen-free (SPF) rhesus monkeys for 11 days in 2006 (R. Desrosiers, personal communication). The SIVmac251 available from the AIDS Reagents Program (SIVmac251_AR) was obtained by passaging splenic lymphocytes of the Mm251-79 primate in the human T cell line HUT-78.11 Bixby et al.8 cloned and sequenced the gp120 of 20 SIVmac251_1991 strains. Keele et al.7 also described 61 envelope sequences obtained from passaging splenocytes of Mm251-79 in human PBMCs, whereas the 25 sequences described by Stone et al.6 were passaged in rhesus monkey's PBMCs. Different SIVmac251_32H viral pools were obtained from new animals that were infected with an uncloned SIVmac251 quasispecies. Finally, additional reference sequences representing known SIVmac clones of different origin were also included in the analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of SIVmac251 Viral Swarms Clones and SIVmac Reference Sequences

| Name | GenBank | Source | Publication Title | Author | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIVmac251_1991 | JF741274–JF741641 | Original animal-titered stock from rhesus macaque 251(PMID 8198874) | Current publication | Current publication | Current publication |

| SIVmac251_2006 | JF741642–JF741834 | 11-day PBMC passage of the original animal-titered stock from rhesus macaque 251 (Desrosiers, personal communication) | Current publication | Current publication | Current publication |

| SIVmac251_ARa | JF741835–JF741921 | Commercially available SIVmac251 stock from Mm251-79 splenocytes passaged in HUT-78 cells (PMID 3159089) | Current publication | Current publication | Current publication |

| SIVmac251_Bixby | HM165237–HM165256 | Original animal-titered SIVmac251 stock from rhesus macaque 251 (PMID 8198874) | Diversity of envelope genes from an uncloned stock of SIVmac251 | Bixby et al. (2010)8 | 20836705 |

| SIVmac251_Keele | FJ578007–FJ578067 | SIVmac251 stock obtained from a cell-free uncloned SIVmac251 stock that was expanded on human PBMCs (PMID 17686853) | Low-dose rectal inoculation of rhesus macaques by SIVsmE660 or SIVmac251 recapitulates human mucosal infection by HIV-1 | Keele et al. (2009)7 | 19414559 |

| SIVmac251_Stone | GU952668–GU952761 | SIVmac251 stock from a short-term expansion of an earlier SIVmac251 stock on rhesus monkey PBMCs | A limited number of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) env variants are transmitted to rhesus macaques vaginally inoculated with SIVmac251 | Stone et al. (2010)6 | 20463069 |

| SIVmac251_32H | M74936–M74941, M74943–M74944 | Molecular clone of 11/88 virus pool from rhesus macaque 32H, which was originally infected with a low passage pool of SIVmac251 | Population sequence analysis of a simian immunodeficiency virus (32H reisolate of SIVmac251): a virus stock used for international vaccine studies | Almond et al. (1992)22 | 1736942 |

| SIVmac251_32H | L35597 | PBMC from macaque 8789 infected with 11/88 SIVmac251(32H) pool | Antigenicity and immunogenicity of recombinant envelope glycoproteins of SIVmac32H with different in vivo passage histories | Hulskotte et al. (1995)23 | 8578803 |

| L35596 | PBMC from macaque 8672 infected with PBMCs from an 11/88 SIVmac32H-infected macaque | ||||

| Reference: 1A11 | M76764 | Molecular clone from tissue culture of virus from rhesus macaque 251 | Genetic and biological comparisons of pathogenic and nonpathogenic molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac) | Luciw et al. (1992)16 | 1571198 |

| Reference: BK28 | M19499 | Molecular clone from tissue culture of virus from rhesus macaque 251 | Sequence of simian immunodeficiency virus and its relationship to the human immunodeficiency viruses | Franchini et al. (1987)24 | 3497350 |

| Reference: EMBL_3 | Y00295 | Provirus from STLV-IIIAGM-infected cell line K6W (PMID 2997923); STLV-IIIAGM was later considered to arise due to laboratory infection by SIVmac251 (PMID 2893293) | Sequence of simian immunodeficiency virus and its relationship to the human immunodeficiency viruses | Franchini et al. (1987)24 | 3497350 |

| Reference: MAC239 | M33262 | Molecular clone from tissue culture of virus from rhesus macaque 239 infected by tissue homogentate of rhesus macaque 61, which was in turn originally infected from tissue homogentate of rhesus macaque 251 | Induction of AIDS in rhesus monkeys by molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus | Kestler et al. (1990)25 | 2160735 |

| Reference: Mac142 | Y00277 | Molecular clone form tissue culture of virus from rhesus macaque 142 infected in utero from mm157-78, which was in contact with numerous macaques and with five males with which she was bred (PMID 2895751) | Sequence of simian immunodeficiency virus from macaque and its relationship to other human and simian retroviruses | Chakrabarti et al. (1987)27 | 3649576 |

| Reference: SIVMM32H_PJ5 | D01065 | Proviral molecular clone, PJ5 from tissue culture of virus from rhesus macaque 32H, originally infected with a low passage pool of SIVmac251 | Molecular and biological characterization of simian immunodeficiency virus macaque strain 32H proviral clones containing nef size variants | Rud et al. (1994)30 | 8126450 |

The following reagent was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: SIVmac251/HUT 78 from Dr. Ronald Desrosiers.

PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

To characterize further the genetic heterogeneity of the major SIVmac251 swarms available, total RNA from the SIVmac251_1991 and SIVmac251_2006 viral swarm was obtained from the New England Primate Research Center (courtesy of Dr. R. Desrosiers). An aliquot of SIVmac251_AR11 viral swarm was also obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, and total RNA was purified using the QIAamp Viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The eluted RNA was used for at least two separate reverse transcriptions using env-specific primers previously described.7 Multiple nested polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed on the cDNA to amplify the full-length gp120 env gene using primers and protocol previously described.12 Amplified products were cloned using the TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and sequenced at the University of Florida Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research Sequencing Core facility to obtain a final data set including 368 clones of SIVmac251_1991, 193 clones of SIVmac251_2006, and 87 clones of SIVmac251_AR. Sequences were assembled with the CodonCode software (CodonCode Corporation, Dedham, MA) and aligned with the Clustal13 algorithm implemented in BioEdit,14 followed by a manual optimization protocol taking into account conserved glycosylation motifs.15 All alignments were gap-stripped for further analyses. The new sequences were deposited in GenBank with accession numbers JF741274–JF741921. The alignments are available from the authors upon request.

To assess for PCR and sequencing errors, PCR and cloning were performed under the same conditions using the 1A11 clone (obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: SIVmac1A11 DNA from Dr. P. Luciw) initially derived from the SIVmac251 swarm as a template.16 To calculate the PCR error rate, 96 clones were sequenced, in both the forward and the reverse direction. The sequences were quality trimmed to 700 bp and aligned using BioEdit. Using the 1A11 sequence as a reference, a pairwise analysis was performed to compute the number of nucleotide differences with MEGA v4.0,17 which resulted in an overall rate of 1.2 errors/kb (1%). All errors were due to point mutations at singleton positions and no recombinant sequences, which could result by Taq polymerase-induced template switching, were detected. To calculate the sequencing error rate, a single clone was sequenced directly 96 times, and only one error was observed overall. To correct for the PCR error rate in the viral sequences, nucleotide changes present in ≤1% per nucleotide position were adjusted to the nucleotide with the highest frequency.

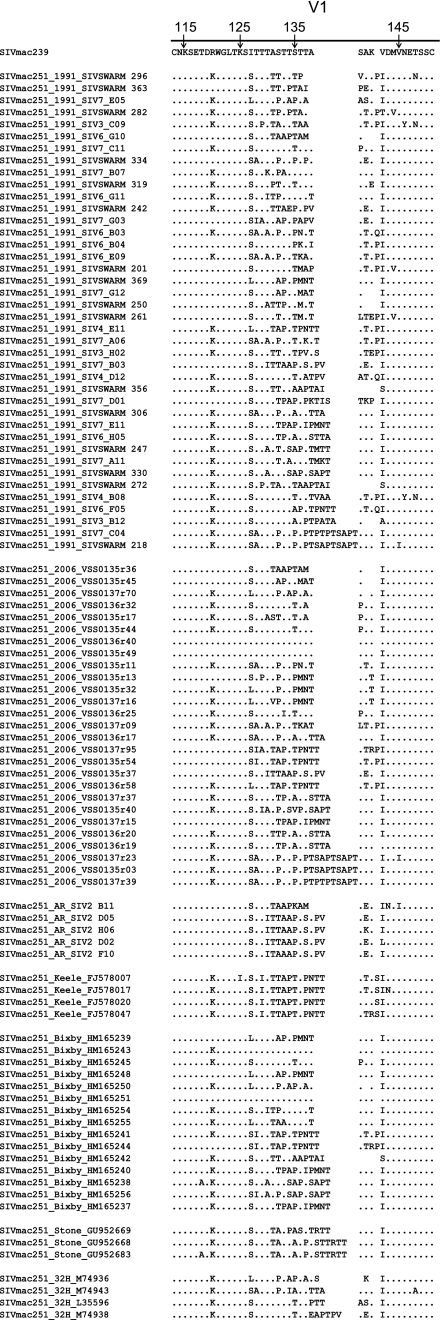

Average within-group diversity for different SIVmac251 stocks was calculated from pairwise distance measures using uncorrected p-distances, and 500 bootstrap replicates to estimate the standard errors, with MEGA v4.0 (Table 2). All the swarms showed a heterogeneous viral population (0.3–1.0%). Interestingly, the diversity of the nonpassaged 20 SIVmac251_Bixby sequences (1.0%±0.4) was not significantly different (two-tailed t-test p>0.05) from that of the 368 SIVmac251_1991 sequences (0.8%±0.2), indicating that a small number of clones is already sufficient to describe the genetic heterogeneity of the original stock, although it may not capture low frequency variants that could significantly contribute to the founder population in newly infected animals. Viral diversity was lower in the four stocks derived from passage/expansion in vitro of SIVmac251, although it was significant only for SIVmac251_AR and SIVmac251_Keele (p<0.05), while not significant (p>0.05) for the SIVmac251_2006 and SIVmac251_Stone (see Table 1). Viral diversity of the animal passaged SIVmac251_32H (0.9%±0.1) was comparable to the SIVmac251_1991. For each viral swarm, the average divergence from SIVmac251_1991 was also calculated. SIVmac251_2006, SIVmac251_ Bixby, and SIVmac251_ Keele showed similar divergence (0.7–0.9%) from SIVmac251_1991 (Table 2). On the other hand, SIVmac251_AR, SIVmac251_Stone, and SIVmac251_32H appeared to be more divergent (1.8–2.1%). As expected, the greatest variability was found in the V1 region both in terms of sequence length polymorphism and amino acid (aa) replacements. In the sequences obtained from both the 1991 and the 2006 SIVmac251 swarm, the length of the V1 region ranged from 36 to 47 aa. There was a reduced length variation (38 to 42 aa) in the Bixby et al.8 sequences. Sequences of different length were also characterized by a different number of glycosylation sites and aa motifs (Fig. 1). Only two distinct length variants (38 and 41 and 42 and 45 aa, respectively) were present in SIVmac251_AR and SIVmac251_Stone, and one distinct length of 42 aa for SIVmac251_Keele.

Table 2.

Genetic Characterization of SIV Viral Swarm Envelope Sequences

| Macaque | Number of sequences | Mean diversitya | Mean divergenceb | V1 length | V1 N-linked glycosylation sites | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIVmac251_1991c | 368 | 0.8 | (0.1) | — | — | 36–47 | 2–3 |

| SIVmac251_2006d | 193 | 0.6 | (0.1) | 0.7 | (0.1) | 36–47 | 2–3 |

| SIVmac251_ARe | 87 | 0.5 | (0.1) | 2.1 | (0.4) | 38, 41 | 2 |

| SIVmac251_Keelef | 61 | 0.3 | (0.1) | 1.0 | (0.2) | 42 | 3 |

| SIVmac251_Bixbyg | 20 | 1.0 | (0.2) | 0.9 | (0.1) | 38–42 | 2–3 |

| SIVmac251_Stoneh | 25 | 0.3 | (0.1) | 2.0 | (0.4) | 42, 45 | 2 |

| SIVMM32H | 10 | 0.9 | (0.1) | 1.8 | (0.3) | 38–44 | 2 |

Average nucleotide diversity (p-distance) of sequences within a specific SIV viral swarm. Values are in %; standard errors are given in parentheses.

Mean nucleotide divergence (p-distance) of viral swarm sequences compared to the 1991 SIVmac251 viral swarm. Values are in %; standard errors are given in parentheses.

1991 viral swarm from New England Primate Center. GenBank accession numbers: JF741274–JF741641.

PBMC passaged (11 days) 1991 viral swarm from New England Primate Center. GenBank accession numbers: JF741642–JF741834.

Viral swarm from AIDS Reagent Program. GenBank accession numbers: JF741835–JF741921.

Viral swarm from Keele et al. (2009).7 GenBank accession numbers: FJ578007–FJ578039.

Viral swarm from Bixby et al. (2010).8 GenBank accession numbers: HM165237–HM165256.

Viral swarm from Stone et al. (2010).6 GenBank accession numbers: GU952668–GU952692.

FIG. 1.

Alignment in the V1 region of representative sequences from the SIVmac251 viral swarm. Sequences are aligned to the SIVmac239 clone used as reference. Identical aa are indicated by a dot. Gaps are represented by blank spaces.

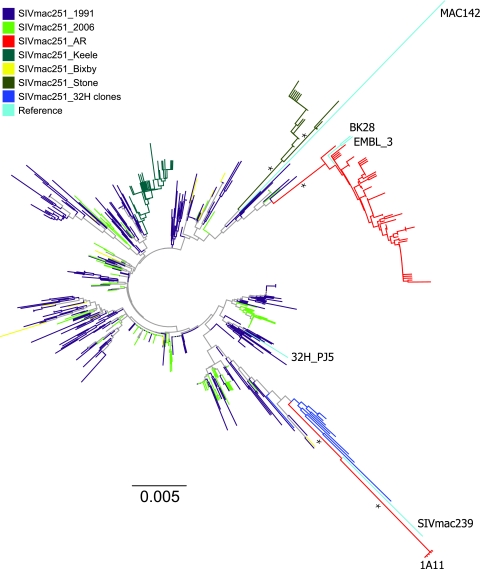

A neighbor-joining tree was inferred, including all the sequences described in Table 1, with the maximum-likelihood composite model implemented in MEGA v4.0 (Fig. 2). Statistical support was assessed by 1000 bootstrap replicates. The similar genetic diversity of SIVmac251_1991 and SIVmac251_2006 and SIVmac251_Bixby was reflected by the star-like phylogeny, in which the sequences from each swarm appeared highly intermixed with low statistical support (<50% bootstrap) for distinct subpopulations. The SIVmac251_AR, SIVmac251_Stone, SIVmac251_32H, and SIVmac251_Keele sequences clustered within distinct monophyletic clades, although only the SIVmac251_AR and the SIVmac251_Stone clades were significantly supported (bootstrap >90%).

FIG. 2.

Neighbor-joining tree of gp120 sequences from the SIVmac251 viral swarms. Sequences were generated from stocks provided by the New England Primate Research Center (SIVmac251_1991, n=368; SIVmac251_2006, n=193) and the AIDS Reagent Program (SIVmac251_AR, n=87). The SIVmac251_Bixby, SIVmac251_Keele, SIVmac251_Stone, SIVmac251_32H, and SIVmac reference sequences were downloaded from GenBank. Accession numbers are given in Table1. The tree was inferred using the maximum-likelihood composite model of nucleotide substitution. Branches are scaled in substitutions/site according to the scale at the bottom the tree. Branches are colored according to the legend in the figure. Supported monophyletic clades (bootstraps ≥75%) are indicated by a star.

This study is the first in-depth sequence comparison and phylogenetic characterization of different sources of SIVmac251 viral swarms. Sequence comparison and phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that the diversity and genetic composition of the original quasispecies were significantly affected by either in vitro or in vivo passage. These results highlight the importance of knowing the origin and passage history of the infecting swarm used in the SIV/macaque model. For example, if a less diverse swarm is used, immunological, pathological, and vaccine development studies may be biased. Moreover, infection with the heterogeneous SIVmac251 quasispecies constitutes a well-established model for studying neuroAIDS.2,18,19 An advantage of using a well-characterized and heterogeneous swarm is the possibility of investigating how the initial transmitting/founder viral population affects brain infection and disease progression. In general, a clear familiarity of the specific viral swarm used in each experiment will play a vital role in future studies by reducing confounding factors and helping to compare results among different experimental settings.20–30

The sequences were deposited in GenBank with accession numbers JF741274–JF741921.

Acknowledgments

M.S. was supported by NIH R01 NS063897-01A2 and AI065265. R.R.G. was funded through T32_NIH_CA_09126. R.R.G., S.S., and M.S. designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. T.H.B, B.N., X.A., and C.C.M. performed the experiments with the animal model. D.J.N. and E.H. designed and performed the SIV sequencing project and developed the protocol to asses and correct PCR/sequencing error rate. K.W. contributed substantially to the study conception. M.M.G. and S.L.L. helped with sequence analysis. We are indebted to Amanda Lowe for assistance with the SIV sequencing and Mattia Prosperi for assistance with the sequence clean-up. We thank Dr. Czerne Reid for assistance editing the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Desrosiers RC. The simian immunodeficiency viruses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:557–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burudi EM. Fox HS. Simian immunodeficiency virus model of HIV-induced central nervous system dysfunction. Adv Virus Res. 2001;56:435–468. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(01)56035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson NA. Watkins DI. Is an HIV vaccine possible? Braz J Infect Dis. 2009;13:304–310. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702009000400013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon MA. Brodie SJ. Sasseville VG. Chalifoux LV. Desrosiers RC. Ringler DJ. Immunopathogenesis of SIVmac. Virus Res. 1994;32(2):227–251. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt RD. Blake BJ. Chalifoux LV. Sehgal PK. King NW. Letvin NL. Transmission of naturally occurring lymphoma in macaque monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80(16):5085–5089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.16.5085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone M. Keele BF. Ma ZM, et al. A limited number of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) env variants are transmitted to rhesus macaques vaginally inoculated with SIVmac251. J Virol. 2010;84:7083–7095. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00481-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keele B. Li H. Learn G, et al. Low-dose rectal inoculation of rhesus macaques by SIVsmE660 or SIVmac251 recapitulates human mucosal infection by HIV-1. J Exp Med. 2009;206(5):1117–1134. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bixby JG. Laur O. Johnson WE. Desrosiers RC. Diversity of envelope genes from an uncloned stock of SIVmac251. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(10):1115–1131. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lena P. Villinger F. Giavedoni L. Miller CJ. Rhodes G. Luciw P. Co-immunization of rhesus macaques with plasmid vectors expressing IFN-gamma, GM-CSF, and SIV antigens enhances anti-viral humoral immunity but does not affect viremia after challenge with highly pathogenic virus. Vaccine. 2002;20(Suppl 4):A69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00391-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinberg MB. Moore JP. AIDS vaccine models: Challenging challenge viruses. Nat Med. 2002;8:207–210. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniel MD. Letvin NL. King NW, et al. Isolation of T-cell tropic HTLV-III-like retrovirus from macaques. Science. 1985;228(4704):1201–1204. doi: 10.1126/science.3159089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephens EB. Liu ZQ. Zhu GW, et al. Lymphocyte-tropic simian immunodeficiency virus causes persistent infection in the brains of rhesus monkeys. Virology. 1995;213:600–614. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson JD. Higgins DG. Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall TA. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;22:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamers SL. Sleasman JW. Goodenow MM. A model for alignment of Env V1 and V2 hypervariable domains from human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12(12):1169–1178. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luciw PA. Shaw KE. Unger RE, et al. Genetic and biological comparisons of pathogenic and nonpathogenic molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac) AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8(3):395–402. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamura K. Dudley J. Nei M. Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anthony IC. Ramage SN. Carnie FW. Simmonds P. Bell JE. Influence of HAART on HIV-related CNS disease and neuroinflammation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64(6):529–536. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell JE. An update on the neuropathology of HIV in the HAART era. Histopathology. 2004;45:549–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis MG. Bellah S. McKinnon K, et al. Titration and characterization of two rhesus-derived SIVmac challenge stocks. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10(2):213–220. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letvin NL. Rao SS. Dang V, et al. No evidence for consistent virus-specific immunity in simian immunodeficiency virus-exposed, uninfected rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2007;81:12368–12374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00822-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almond N. Jenkins A. Slade A. Heath A. Cranage M. Kitchin P. Population sequence analysis of a simian immunodeficiency virus (32H reisolate of SIVmac251): A virus stock used for international vaccine studies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8(1):77–88. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulskotte EG. Rimmelzwaan GF. Boes J, et al. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of recombinant envelope glycoproteins of SIVmac32H with different in vivo passage histories. Vaccine. 1995;13:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franchini G. Gurgo C. Guo HG, et al. Sequence of simian immunodeficiency virus and its relationship to the human immunodeficiency viruses. Nature. 1987;328(6130):539–543. doi: 10.1038/328539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kestler H. Kodama T. Ringler D, et al. Induction of AIDS in rhesus monkeys by molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus. Science. 1990;248(4959):1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.2160735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniel MD. Letvin NL. Sehgal PK, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to 3 retroviruses in a captive colony of macaque monkeys. Int J Cancer. 1988;41(4):601–608. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910410421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakrabarti L. Guyader M. Alizon M, et al. Sequence of simian immunodeficiency virus from macaque and its relationship to other human and simian retroviruses. Nature. 1987;328(6130):543–547. doi: 10.1038/328543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanki PJ. Alroy J. Essex M. Isolation of T-lymphotropic retrovirus related to HTLV-III/LAV from wild-caught African green monkeys. Science. 1985;230(4728):951–954. doi: 10.1126/science.2997923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kestler HW., 3rd Li Y. Naidu YM, et al. Comparison of simian immunodeficiency virus isolates. Nature. 1988;331(6157):619–622. doi: 10.1038/331619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rud EW. Cranage M. Yon J, et al. Molecular and biological characterization of simian immunodeficiency virus macaque strain 32H proviral clones containing nef size variants. J Gen Virol. 1994;75(Pt 3):529–543. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-3-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]