Abstract

Recurrent aphthous ulcers are common painful mucosal conditions affecting the oral cavity. Despite their high prevalence, etiopathogenesis remains unclear. This review article summarizes the clinical presentation, diagnostic criteria, and recent trends in the management of recurrent apthous stomatitis.

Keywords: Diagnostic criteria, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, stress ulcers, ulcer activity index immunomodulation

INTRODUCTION

The term “aphthous” is derived from a Greek word “aphtha” which means ulceration. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) is one of the most common painful oral mucosal conditions seen among patients. These present as recurrent, multiple, small, round, or ovoid ulcers, with circumscribed margins, having yellow or gray floors and are surrounded by erythematous haloes, present first in childhood or adolescence.[1]

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

RAS is characterized by recurrent bouts of solitary or multiple shallow painful ulcers, at intervals of few months to few days in patients who are otherwise well.[2] RAS has been described under three different clinical variants as classified by Stanley in 1972.[3]

Minor RAS is also known as Miculiz's aphthae or mild aphthous ulcers. It is the most common variant, constituting 80% of RAS. Ulcers vary from 8 to 10 mm in size. It is most commonly seen in the nonkeratinized mucosal surfaces like labial mucosa, buccal mucosa, and floor of the mouth. Ulcers heal within 10–14 days without scarring.

Major RAS is also known as periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens or Sutton's disease. It affects about 10–15% of patients. Ulcers exceed 1 cm in diameter. Most common sites of involvement are lips, soft palate, and fauces. Masticatory mucosa like dorsum of tongue or gingiva may be occasionally involved.[4] The ulcers persist for up to 6 weeks and heal with scarring.

Herpetiform ulceration is characterized by recurrent crops of multiple ulcers; may be up to 100 in number. These are small in size, measure 2–3 mm in diameter. Lesions may coalesce to form large irregular ulcers. These ulcers last for about 10–14 days. Unlike herpetic ulcers, these are not preceded by vesicles and do not contain viral infected cells. These are more common in women and have a later age of onset than other clinical variants of RAS.[5]

Predisposing factors

Genetics

A genetic predisposition for the development of apthous ulcer is strongly suggested as about 40% of patients have a family history and these individuals develop ulcers earlier and are of more severe nature.[2] Various associations with HLA antigens and RAS have been reported. These associations vary with specific racial and ethnic origins.

Trauma

Trauma to the oral mucosa due to local anesthetic injections, sharp tooth, dental treatments, and tooth brush injury may predispose to the development of recurrent aphthous ulceration (RAU).[1] Wray et al.[6] in 1981 proposed that mechanical injury may aid in identifying and studying patients prone to aphthous stomatitis.

Tobacco

Several studies reveal negative association between cigarette smoking, smokeless tobacco and RAS. Possible explanations given include increased mucosal keratinization; which serves as a mechanical and protective barrier against trauma and microbes.[7–9] Nicotine is considered to be the protective factor as it stimulates the production of adrenal steroids by its action on the hypothalamic adrenal axis and reduces production of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins 1 and 6 (IL-1 andIL-6).[10] Nicotine replacement therapy has been suggested as treatment for patients who develop RAU on cessation of smoking.[11]

Drugs

Certain drugs have been associated with development of RAU; these include angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor captopril, gold salts, nicorandil, phenindione, phenobarbital, and sodium hypochloride. NSAIDS such as propionic acid, diclofenac, and piroxicam may also cause oral ulceration similar to RAS.[12]

Hematinic deficiency

Deficiencies of iron, vitamin B12, and folic acid predispose development of RAS. Deficiencies of these hematinics are twice more common in these individuals than controls. Contrary findings in various studies relating the association of hematinic deficiency and RAS have been explained as due to varying genetic backgrounds and dietary habits of the study population.[2,12]

Gluten sensitive enteropathy/celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease

Gluten sensitive enteropathy (GSE) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease of small intestine that is precipitated by the ingestion of gluten, a wheat protein in susceptible individuals. It is characterized by severe malnutrition, anemia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, aphthous oral ulcers, glossitis, and stomatitis. RAS may be the sole manifestation of the disease. The use of gluten-free diet in the improvement of RAS is considered uncertain. It has been suggested that evaluation for celiac disease may be appropriate for RAS patients.[13] Inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis may present with apthous-like ulceration.[1]

Sodium lauryl sulfate - containing toothpaste

An increased frequency in the occurrence of RAS has been reported on using sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS)-containing tooth paste with some reduction in ulceration on use of SLS-free tooth paste. However, because of the widespread use of SLS-containing dentifrice, it has been proposed that this may not truly predispose to RAS.[1]

Hormonal changes

Conflicting reports exist regarding association of hormonal changes in women and RAU. Studies state association of oral ulceration with onset of menstruation or in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Mc Cartan et al.[14] in 1992 established no association between apthous stomatitis and premenstrual period, pregnancy, or menopause.

Stress

Stress has been emphasized as a causative factor in RAU. It has been proposed that stress may induce trauma to oral soft tissues by parafunctional habits such as lip or cheek biting and this trauma may predispose to ulceration. A more recent study shows lack of direct correlation between levels of stress and severity of RAS episodes and suggests that psychological stress may act as a triggering or modifying factor rather than etiological factor in susceptible RAS patients.[15]

Micro organisms implicated in apthous ulcers

Several micro organisms have been implicated in the pathogenesis of RAS. Several contrary findings have been reported in the various studies published.

RAS and oral streptococci

Oral streptococci have been considered as microbial agents in the pathogenesis of RAS. They have been implicated as microorganisms directly involved in the pathogenesis of these lesions or as agents which serve as antigenic stimuli, which in turn provoke antibody production that cross-react with oral mucosa. It has been suggested that L form of α-hemolytic streptococci, Streptococcus sanguis; later identified as Streptococcus mitis was the causative agent of this disease. Hoover et al.[16] in 1986 demonstrated low levels of cross-reactivity of oral Streptococci and oral mucosal antigens and considered the reactivity to be non-specific and clinically insignificant.

RAS and Helicobacter pylori

H. pylori has been implicated as one of the organisms in the etiopathogenesis of RAS. H. pylori is a gram-negative, S-shaped bacterium that has been associated with gastritis and in chronically infected duodenal ulcers. H. pylori has been reported to be present in high density in dental plaque.[17] Porter et al.[18] in 1997 measured the levels of IgG antibodies against H. pylori in patients with RAS and showed that no the frequency of anti-H. pylori seropositivity was not significantly elevated in patients with RAS and other ulcerative and non-ulcerative oral mucosal disorders.

Viruses as etiologic agents in RAS

Various viruses have been implicated in the etiopathogenesis of recurrent apthous stomatitis. There have been several suggestive, but as yet there exists inconclusive evidence toward a viral etiology. Characteristics of aphthous ulcers which are indicative of infectious etiology include recurrent ulceration, lymphocytic infiltration, perivascular cuffing, presence of auto-antibodies, inclusion bodies in case of herpetiform ulcers and similarity of RAU to viral ulcerative diseases in animals.[19] Virtanen et al.[17] in 1995 demonstrated the presence of human cytomegalovirus DNA (HCMV) in biopsies of oral mucosal ulcers, but they were unable to rule out the presence of this virus which may have existed as a super infection or co infection from existing HCMV in saliva. Sun et al.[20] in 1996 demonstrated the presence of HCMV genomes by polymerase chain reaction in pre-ulcerative oral apthous tissues. They postulated that when viral infection occurs in oral epithelial cells expressing major histocompatibility complex class II molecules (MHC-II), an intense T-cell response is elicited against virus containing oral epithelial cells. They concluded that HCMV may play role in perpetuating local immune response in genetically predisposed individuals.

Sun et al.[21] in 1998 demonstrated the presence of Epstein-barr virus (EBV) genomes by polymerase chain reaction in pre-ulcerative oral apthous tissues in RAU patients. They postulated a possible role of association of EBV in pre-ulcerative oral lesions in patients of RAU.

Role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in RAS

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine and is one of the most important cytokine implied in the development of new apthous ulcers in patients. The association of TNF-α in the development of RAS gains credence due to the fact that immunomodulatory drugs such as thalidomide and pentoxifylline have been found effective in the treatment of RAS. Thalidomide reduces activity of TNF-α by degrading its messenger RNA and pentoxifylline inhibits TNF-α production.[22,23] Antigenic stimulation of oral mucosal keratinocytes results in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-2 and TNF-α. TNF-α also causes expression of class I major histocompatability complex, subsequently these cells are targeted for attack by cytotoxic T cells.[1]

INDEX FOR DETERMINING IMPACT OF ORAL ULCER ACTIVITY IN PATIENTS OF RAS

Mumucu et al.[24] in 2009 proposed a composite index to monitor the clinical manifestations associated with oral ulcers in patients of RAS and Behcet's disease. They proposed that such indices serve to provide important information regarding prognosis of disease and therapeutic effect of medication.

The index evaluated the oral ulcer activity, ulcer-related pain, and functional disability. Oral ulcer activity was recorded as number of ulcers in the past 1 month. This was scored zero if there were no ulcers and as one, if the number of ulcer was greater or equal to than one. The pain status was evaluated on a visual analogue scale (VAS). This is a 100-mm line with extreme values at either end. The patients have to mark the intensity of pain on the line.

Functional status evaluation

This involved the evaluation of effects of oral ulcers on tasting, speaking, and eating/chewing/swallowing. This was evaluated by both Likert-type scale and VAS scale. Scoring is done as 0, when none of the time; 1, little of the time; 2, some of the time; 3, most of the time; 4, all of the time and VAS (0–100 mm).

Use of visual analog scale to evaluate the pain caused by ulcers is highly subjective and is ridden with interpersonal variation. This is a continuous scale with no discrete levels as would be suggested by grades such as none, mild, moderate, or severe. Further studies in different population and ethnic groups need to be carried out using this criteria to validate this index.

HISTOPATHOLOGY OF RAS

The microscopic picture of aphthous ulcer is non-specific, and diagnosis must be based on history and careful clinical examination. The mucous membrane of aphthous ulcer shows superficial tissue necrosis with a fibrinopurulent membrane covering the ulcerated area. The necrosis is covered by tissue debris and neutrophils. Epithelium is infiltrated by lymphocytes and few neutrophils. Intense inflammatory cell infiltration, predominantly neutrophils present immediately below the ulcer, mononuclear lymphocytes are seen in adjacent areas. Minor salivary glands commonly present in areas of aphthae exhibit focal periductal and perialveolar fibrosis and chronic inflammation.[12,25]

DIAGNOSIS

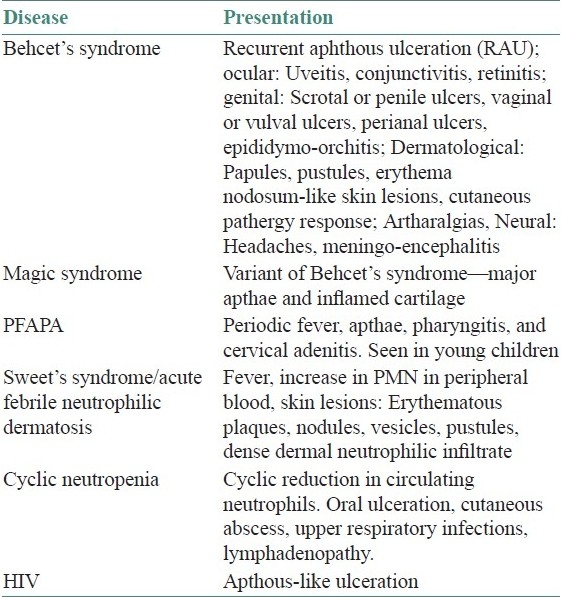

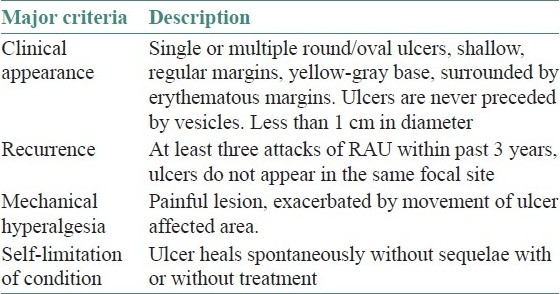

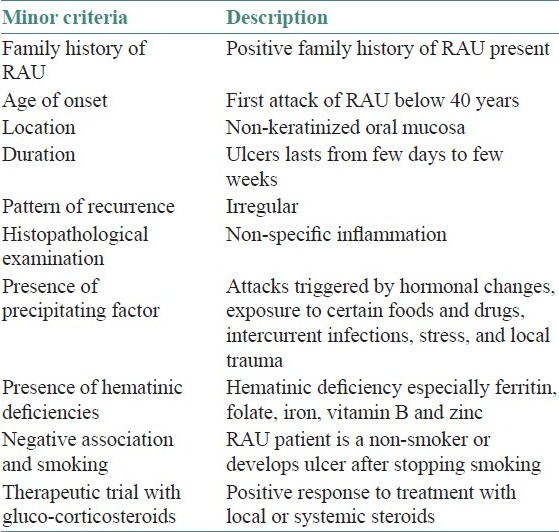

Diagnosis of RAS is based on history, clinical manifestations, and histopathology. Other causes of recurrent oral ulceration must be ruled out. Systemic diseases which present with recurrent oral ulcerations are summarized in Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for minor RAU were proposed by Natah et al.[12] in 2004. They proposed that a diagnosis of idiopathic RAU and secondary RAU (associated with systemic disease) is established when four major and one minor criteria are fulfilled. The major and minor criteria for diagnosis of minor RAU are illustrated in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Systemic diseases with recurrent oral ulceration (modified from reference 1)

Table 2.

Major criteria for diagnosis of RAU minor (Natah et al.[12] 2004)

Table 3.

Minor criteria for diagnosis of RAU minor

Management

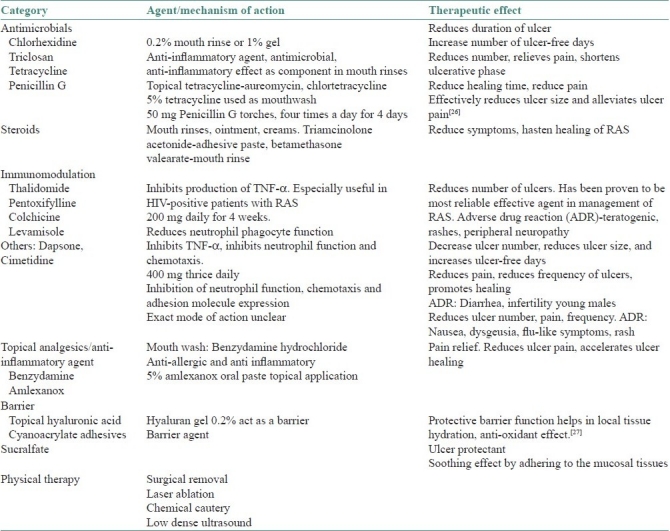

There is no definitive curative treatment for RAS. Possible systemic association with RAS must be ruled out, especially in cases where there is sudden development of ulceration in adulthood.[2] Laboratory investigations such as complete blood counts, red cell folate, serum ferritin levels, and vitamin B12 recommended. Screening for GSE must be done in cases where associated systemic manifestations of GSE are present. Various topical and systemic agents used in treatment of RAS are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Topical and systemic agents used in treatment of RAS

CONCLUSION

Recurrent apthous stomatitis is a very common, recurrent painful ulceration occurring in the oral cavity. The etiopathogenesis of this disease is yet unclear. Treatment strategies must be directed toward providing symptomatic relief by reducing pain, increasing the duration of ulcer-free periods, and accelerating ulcer healing.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jurge S, Kuffer R, Scully C, Porter SR. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Oral Dis. 2006;12:1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scully C, Porter S. Oral mucosal disease: Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.07.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanley HR. Aphthous lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1972;30:407–16. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(72)90470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cawson RA, Odell EW. Cawson's Essentials of Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elseivier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scully C, Porter S. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: Current concepts of etiology, pathogenesis and management. J Oral Pathol Med. 1989;18:21–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1989.tb00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wray D, Graykowski EA, Notkins AL. Role of mucosal injury in initiating recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;283:1569–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6306.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bookman R. Relief of Canker Sores on Resumption of Cigarette Smoking. Calif Med. 1960;93:235–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro S, Olson DL, Chellemi SJ. The association between smoking and aphthous ulcers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1970;30:624–30. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(70)90384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grady D, Ernster VL, Stillman L, Greenspan J. Smokeless tobacco use prevents aphthous stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:463–65. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Floto RA, Smith KG. The vagus nerve, macrophages and nicotine. Lancet. 2003;361:1069–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheid P, Bohadana A, Martinet Y. Nicotine patches for aphthous ulcers due to Behcet's syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1816–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012143432418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Natah SS, Konttinen YT, Enattah NS, Ashammakhi N, Sharkey KA, Häyrinen-Immonen R. Recurrent aphthous ulcers today: A review of growing knowledge. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:221–34. doi: 10.1006/ijom.2002.0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shakeri R, Zamani F, Sotoudehmanesh R, Amiri A, Mohamadnejad M, Davatchi F, et al. Gluten sensitive enteropathy in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCartan BE, Sullivan A. The association of menstrual cycle, pregnancy and menopause with recurrent oral aphthous stomatitis: A review and critique. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:455–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallo Cde B, Mimura MA, Sugaya NN. Pschological stress and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64:645–8. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000700007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoover CI, Olson JA, Greenspan JS. Humoral responses and cross reactivity to viridians streptococci in recurrent aphthous ulceration. J Dent Res. 1986;65:1101–4. doi: 10.1177/00220345860650081101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leimola-Virtanen R, Happonen RP, Syrjänen S. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Helicobacter pyroli (HP) found in oral mucosal ulcers. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:14–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porter SR, Barker GR, Scully C, Macfarlane G, Bain L. Serum IgG antibodies to Helicobacter pyroli in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis and other oral disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:325–8. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooks JJ. Possibility of a viral etiology in recurrent aphthous ulcers and Behcet's syndrome. J Oral Pathol. 1978;7:353–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1978.tb01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun A, Chang JG, Kao CL, Liu BY, Wang JT, Chu CT, et al. Human cytomegalovirus as a potential etiologic agent in recurrent aphthous ulcers and Behcet, s disease. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:212–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun A, Chang JG, Chu CT, Liu BY, Yuan JH, Chiang CP. Preliminary evidence for an association of Epstein – Barr virus with pre-ulcerative oral lesions in patients with recurrent aphthous ulcers or Behcet's disease. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:168–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson JM, Greenspan JS, Spritzler J, Ketter N, Fahey JL, Jackson JB, et al. Thalidomide for the treatment of oral aphthous ulcers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Clinical Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1487–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705223362103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zabel P, Schade FU, Schlaak M. Inhibition of endogeneous TNF-α formation by pentoxifylline. Immunobiology. 1993;187:447–63. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mumcu G, Sur H, Inanc N, Karacayli U, Cimilli H, Sisman N, et al. A composite index for determining the impact of oral ulcer activity in Behcet's disease and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:785–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shafer, Hine, Levy . A Textbook of Oral Pathology. 4th ed. New Delhi: Saunders; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y, Chen Q, Meng W, Jiang L, Wang Z, Liu J, et al. Evaluation of penicillin G potassium troches in the treatment of minor recurrent aphthous ulceration in a Chinese cohort: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo and no- treatment- controlled, multicenter clinical trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:561–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nolan A, Baillie C, Badminton J, Rudralingam M, Seymonr RA. Efficacy of topical hyaluronic acid in the management of recurrent aphthous ulceration. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35:461–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]