Abstract

Recent attention has been directed toward the role of mast cells in the pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Mast cells are responsible for trafficking inflammatory cells into the connective tissue that in turn helps in progression and maintenance of chronicity of oral lichen planus (OLP). OLP is a T-cell-mediated chronic inflammatory oral mucosal disease of unknown etiology, and lesions contain few B-cells or plasma cells and minimal deposits of immunoglobulin or complement. Hence, OLP is ideally positioned for the study of human T-cell-mediated inflammation and autoimmunity. This study was done to evaluate the mast cell count using toluidine blue stain in OLP and compares it with oral lichenoid reaction (OLR), and to propose the possible role of mast cells in the pathogenesis of OLP and OLR. Ten cases each of OLP and OLR and five cases of normal buccal mucosa were taken from the archives of Department of Oral Pathology. The samples were stained with toluidine blue using standard toluidine blue method by Wolman 1971. An increase in mast cell count was observed in OLP and OLR in comparison to normal oral mucosa. However, no significant differences in mast cell count were noted between OLP and OLR.

Keywords: Lichen planus, lichenoid reaction, mast cells

INTRODUCTION

Paul Ehrlich in 1877 discovered a granular cell of loose connective tissue and named it as “Mastzellan”—a well fed cell.[1] Studies on mast cells in normal and various pathologic conditions have shown them to be complex, well-engineered, multifunctional cell playing a central role in acquired and innate immunity.

Mast cells have a diameter of about 12 μm, they are heterogenous in shape, and round, oval, or spindle-shaped, and are packed with 50–100 granules. They have a life span of weeks to months.[2,3] Mast cells have some preformed mediators such as cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α histamine, chymase, and tryptase in their cytoplasmic granules that stain metachromatically under normal circumstances.[4] These mediators are deposited in large quantities in the extracellular compartments following degranulation where they exert stimulatory, inhibitory, or toxic effect on neighboring cells.[5] The ability of mast cells to degranulate in response to various stimuli including drugs and chemicals is the very basis for their biologic activity.[6]

Although there is a sizeable literature on T-cell populations in oral lichen planus (OLP), other immunocompetent cells have attracted less attention. An increased number of mast cells is a consistent finding in OLP.[7] However, the frequency of occurrence of mast cells in oral lichenoid reaction (OLR), a condition clinically and histopathologically similar to OLP, has not been extensively studied.

This study was aimed at evaluating the mast cell count in OLP and OLR. An attempt is also made to propose the possible role of mast cells in the pathogenesis of OLP and OLR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were obtained from the archives of the Department of Oral Pathology, D J College of Science and Research, Modinagar. Sample consisted of 10 cases each of OLP and OLR which had been diagnosed using World Health Organization criteria.[8] Five biopsies of normal oral mucosa were included as control. All tissue sections were stained using standard toluidine blue stain,[9] which gave light blue background to the section and allowed easy mapping of metachromatically stained mast cells.

Based on the intensity of metachromasia, mast cells were categorized into two groups:[10]

intact mast cells exhibiting intense metachromasia and dense granules obscuring the nucleus and

Degranulated mast cells with less intense metachromasia and clear outline of the nucleus.

Mast cell evaluation was done using Motic BA400 microscope. To determine the mast cell count, three different high-power fields in the connective tissue were selected without any overlapping and avoiding the edges of sections. In each of these areas, mast cells were counted at two different levels, described as zone I and zone II.

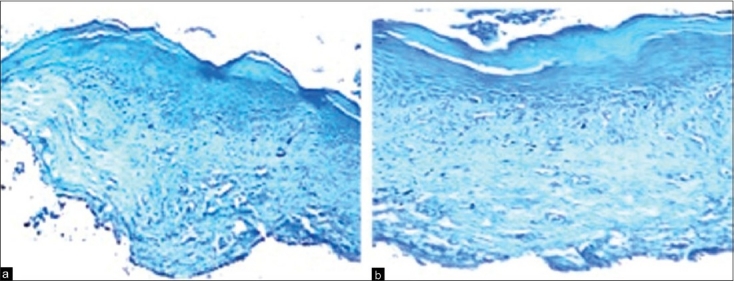

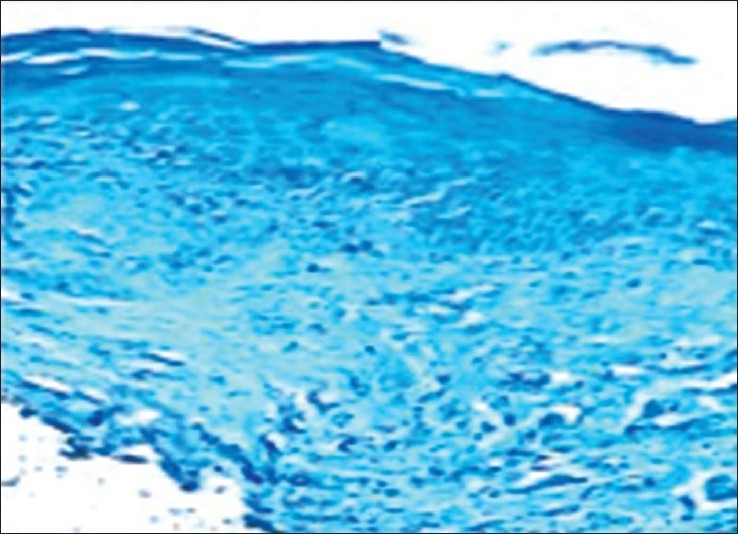

The two zones are described as follows: Zone I—subepithelially within the inflammatory cell infiltrate [Figure 1a and b] and zone II—within the deeper layer below the inflammatory cell infiltrate [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

(a) Photomicrograph showing mast cells in connective tissue of normal oral mucosa (4× toluidine blue stain). (b) Photomicrograph showing mast cells in subepithelial zone of lichen planus (10× toluidine blue stain)

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing mast cells in deeper connective tissue of lichen planus (10× toluidine blue stain)

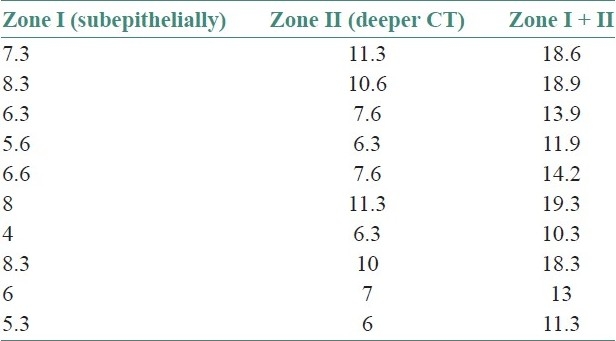

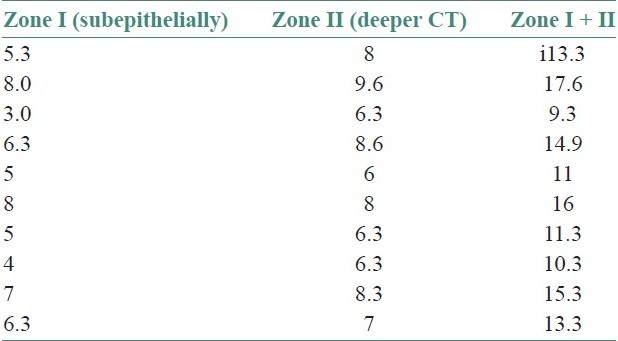

In each of the tissue sections, the mean number of mast cells were calculated and expressed as cells/unit area. The statistical analysis was done using Dunnett's method followed by one-way analysis of variance to compare the significant difference between the control and experimental group (zone I and zone II in OLP and OLR) at 1% level of significance [Tables 1 and 2] and unpaired t?test to compare the significant difference between OLP and OLR.

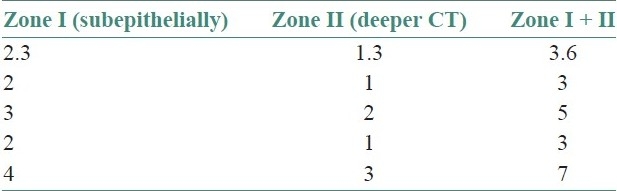

Table 1.

Total mast cell count in oral lichen planus

Table 2.

Total mast cell count in oral lichenoid reaction

RESULTS

In toluidine blue-stained sections, mast cells were clearly identifiable in all the three groups, by their metachromatically stained granules.

The quantitative evaluation of mast cells revealed that out of 10 cases of OLP and 10 cases of OLR, there was a significant increase in the number of mast cells in all cases when compared with control (P<.01). There was no statistically significant difference between the total number of mast cells in OLP and OLR (P>0.01). In all cases of OLP and OLR, mast cells were more in zone II, than in zone 1 [Tables 3 and 4], while the control cases showed more mast cells in zone I [Table 5].

Table 3.

Total mast cell count in normal oral mucosa

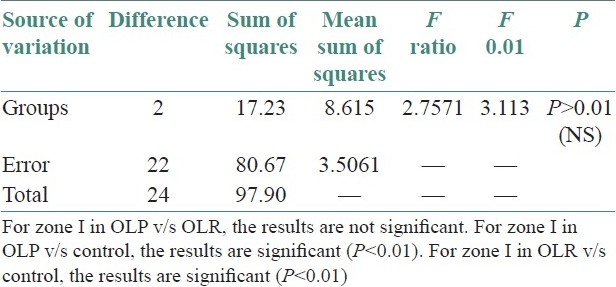

Table 4.

Analysis of variance test

Table 5.

Analysis of variance test

+6.74: Difference between zone II OLP and control group, hence zone II demonstrated more number of mast cells in OLP than control group.

+5.78: Difference between zone II OLR and control group, hence zone II demonstrated more number of mast cells in OLR compared with control group.

The statistical analysis was done by using Dunnett's method followed by one-way analysis of variance to compare the significant difference between mast cells in control and experimental group, i.e., OLP and OLR at 1% level of significance.

Significant difference was observed between mast cells of control and experimental groups for zone II at 1% level of significance, by Dunnett's method and hence, zone II was found better in OLP and OLR in comparison to control group. Unpaired t-test was applied and comparison was also done between zone I and zone II of OLP and OLR. No significant difference was observed between OLP and OLR in zone I and zone II.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have observed a significant increase when compared with normal, in the total mast cell count in OLP and OLR, which confirms the importance of mast cells in the pathogenesis for both the conditions. This finding of increased number of mast cells is consistent with previous studies.[5] This observation may also indicate similarity in pathogenesis of both these conditions.

In OLP and OLR, greater number of mast cells were seen in deeper connective tissue (zone II) when compared with subepithelial connective tissue. Jose et al. noted larger number of degranulating mast cells in the subepithelial zone.[10] This was explained by the fact that mast cells that migrated from blood vessels in the deeper connective tissue to the extravascular compartment subsequently moved toward the subepithelial zone, where they exert their biologic effect on blood vessels and help in recruitment of inflammatory cells to the lesional area. However, in our study using toluidine blue, we could not conclusively differentiate between intact and degranulated mast cells.

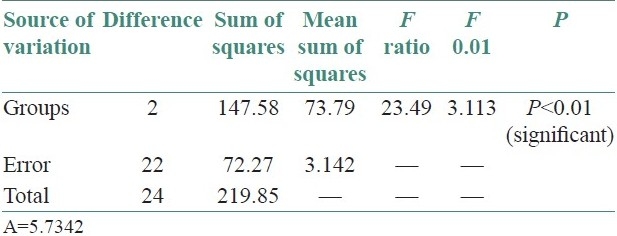

At the cellular level, OLP probably results from an immunologically induced apoptosis of the basal keratinocytes, due to cytotoxic CD8+ cell response on modified keratinocyte surface antigen.

The degranulation of mast cells in OLP may be initiated by two different mechanisms[11]

Following the interaction of T cells in a MHC class I or class II manner, the resultant T-cell activation activates mast cells leading to degranulation and cytokine release [Figure 3].

Second, chemokine could induce a calcium influx that would cause direct degranulation of mast cells with release of TNF-α, which stimulate T cell to produce cytokine or chemokine.

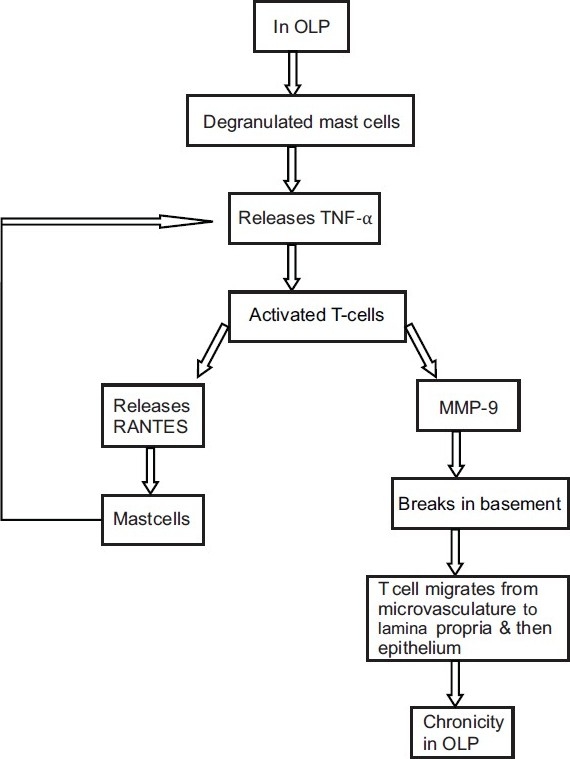

Figure 3.

Degranulation of mast cells following T-cell interaction

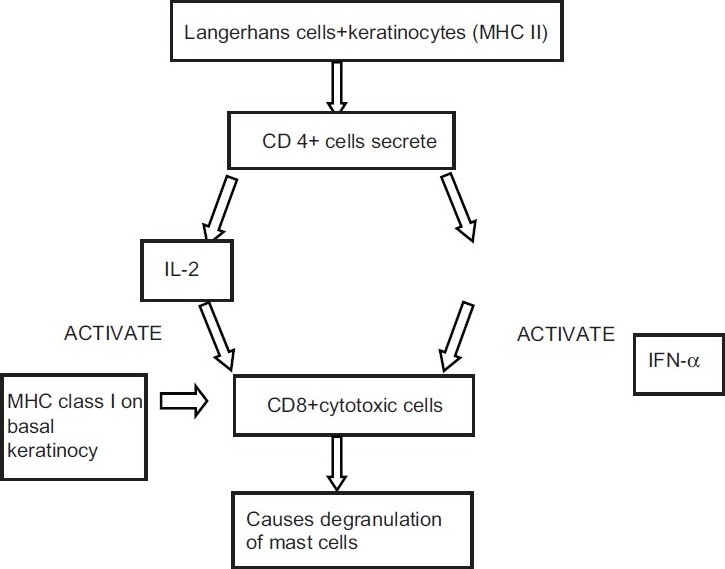

There is a growing awareness that oral mucosal T lymphocytes and mast cells interact in a bidirectional fashion in maintaining the chronicity and the pathogenesis of OLP. In the development of the lesion, mast cell-derived TNF-α activates T cells which further secrete RANTES and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP). RANTES causes continued degranulation of mast cells, while MMPs prepare the endothelium and the surrounding connective tissue matrix for the migration of T cells[7] [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Interaction of mast cells showing their bidirectional role in pathogenesis of OLP

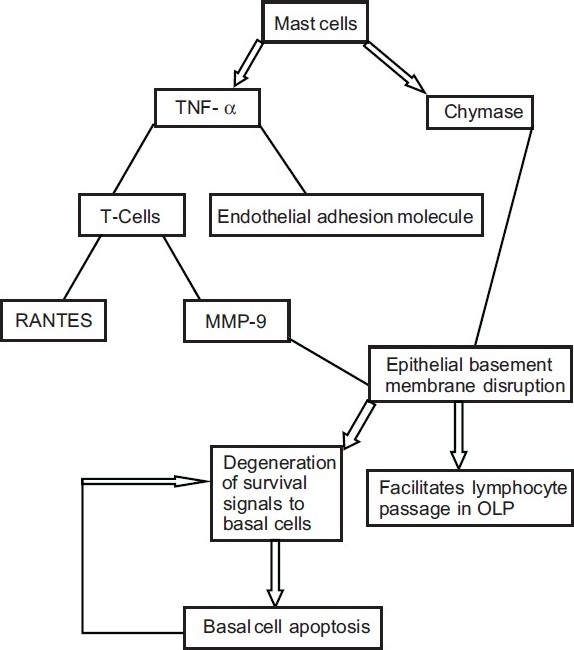

A number of investigators have demonstrated an increased mast cell density and mast cell degranulation in OLP.[11] It has been shown that on degranulating, these mast cells release a range of both preformed and newly synthesized cytokines and chemokines. These cytokines act by different mechanisms to maintain the OLP lesion [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Overall effect of mast cells in pathogenesis of OLP

Degranulating mast cell release TNF-α that upregulates endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression for lymphocutes adhesion and extravasation.

Mast cell TNF-α also upregulates RANTES and MMP-9 secretion by OLP lesional T cells. Activated lesional T cells secrete chemokines that attract extravasated lymphocytes toward the OLP epithelium.

Degranulating mast cells release chymase (a mast cell protease) that damages the epithelial basement membrane directly or indirectly via activation of matrix metalloprotein-9 secreted by OLP lesional T cells.

Thus, the role of mast cells in pathogenesis of OLR is well elucidated. As the number of mast cells is significantly increased in OLR as well, we propose a similar pathogenetic mechanism for the same. The triggering factor in case of OLP is an unknown antigen,[12] while in case of OLR it may be a food, drug, or dental restorative material. Thus, if the antigen is identifiable, appropriate management may cause resolution of the lesion. However, chronicity is seen if the antigen cannot be specifically identified. Thus, clinical examination and detailed history is of prime importance in the management of OLP and OLR lesions.

CONCLUSION

The pathogenesis aspect of both OLP and OLR are well understood from the functional relationships between mast cells and T cells, and the only difference exists in the etiological factor. Clinical examination procedures are of prime importance in management of lichen planus and lichenoid lesions. The role of various chemokines and cytokines in these conditions may eventually lead to novel therapies for their management.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Riley JF. In: Mast cells. 2nd ed. Livingston E, Livingston S, editors. Edinburg h London: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ham WA, Cormack HD, editors. Histology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company; 1979. The origins, morphologies and functions of the cells of the loose connective tissue; pp. 225–59. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence B. Haemolymphoid system. In: Lawrence B, Martin BM, Patricia C, Mary D, Juhan D, editors. Gray's Anatomy. 38th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston Harcourt Publishers Ltd; 2000. pp. 1399–451. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh LJ, Kaminer MS, Lazarus GS, Lavker RM, Murphy GF. Role of laminin in localization of human dermal mast cells. Labs Invest. 1991;65:433–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh LJ, Davis MF, Xu LJ, Savege NW. Relationship between mast cell degranulation and inflammation in the oral cavity. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:266–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh LJ, Savege NW, Ishil T, Seymour GJ. Immuno pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19:389–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1990.tb00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao ZZ, Savage NW, Sugerman PB, Walsh LJ. Mast cell/T cell interactions in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:189–95. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2002.310401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rad M, Hashemipoor MA, Mojtahedi A, Zarei MR, Chamani G, Kakoei S, et al. Correlation between clinical and histopathologic diagnosis of oral lichen planus based on modified WHO diagnostic criteria. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:796–800. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bancroft JD, Cook HC, Sterling RW. Manual of histologic technique and their diagnostic application. Philadelphia (US): Churchill Livingstone; 1994. pp. 112–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jose M, Raghu AR, Rao NN. Evaluation of mast cells in oral lichen planus and oral Lichenoid reaction. Indian J Dent Res. 2001;12:175–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jontell VM, Hansson HA, Nygren H. Mast cells in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol. 1986;15:273–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1986.tb00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ismail SB, Kumar SK, Zain RB. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid reactions: Etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, management and malignant transformation. J Oral Sci. 2007;49:89–106. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.49.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]