Abstract

Background:

Although nalbuphine was studied extensively in labour analgesia and was proved to be acceptable analgesics during delivery, its use as premedication before induction of general anesthesia for cesarean section is not studied. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of nalbuphine given before induction of general anesthesia for cesarean section on quality of general anesthesia, maternal stress response, and neonatal outcome.

Methods:

Sixty full term pregnant women scheduled for elective cesarean section, randomly classified into two equal groups, group N received nalbuphine 0.2 mg/kg diluted in 10 ml of normal saline (n=30), and group C placebo (n=30) received 10 ml of normal saline 1 min before the induction of general anesthesia. Maternal heart rate and blood pressure were measured before, after induction, during surgery, and after recovery. Neonates were assisted by using APGAR0 scores, time to sustained respiration, and umbilical cord blood gas analysis.

Result:

Maternal heart rate showed significant increase in control group than nalbuphine group after intubation (88.2±4.47 versus 80.1±4.23, P<0.0001) and during surgery till delivery of baby (90.8±2.39 versus 82.6±2.60, P<0.0001) and no significant changes between both groups after delivery. MABP increased in control group than nalbuphine group after intubation (100.55±6.29 versus 88.75±6.09, P<0.0001) and during surgery till delivery of baby (98.50±2.01 versus 90.50±2.01, P<0.0001) and no significant changes between both groups after delivery. APGAR score was significantly low at one minute in nalbuphine group than control group (6.75±2.3, 8.5±0.74, respectively, P=0.0002) (27% of nalbuphine group APGAR score ranged between 4–6, while 7% in control group APGAR score ranged between 4–6 at one minute). All neonates at five minutes showed APGAR score ranged between 9–10. Time to sustained respiration was significantly longer in nalbuphine group than control group (81.8±51.4 versus 34.9±26.2 seconds, P<0.0001). The umbilical cord blood gas was comparable in both groups. None of the neonates need opioid antagonist (naloxone) or endotracheal intubation.

Conclusion:

Administration of nalbuphine before cesarean section under general anesthesia reduces maternal stress response related to intubation and surgery, but decreases the APGAR score at one minute after delivery. So, when nalbuphine was used, all measures for neonatal monitoring and resuscitation must be available including attendance of a pediatrician.

Keywords: Anesthesia, cesarean section, nalbuphine, neonates, obstetric, obstetric analgesia

INTRODUCTION

Anesthesia is composed of three components, hypnosis, muscle relaxation, and analgesia. Missing one of these limbs will lead to serious effect on the patients, for example, lack of hypnosis lead to awareness; also lack of analgesia will lead to exaggerated response to painful stimulus with increased catecholamine levels in the blood, which increase the blood pressure, heart rate, and intracranial pressure. The anesthetists use different drugs with the objective to achieve a balance between analgesia and hypnosis.[1]

Opioids are considered the gold standard for achieving good anesthetic practice.[1] However, in obstetric anesthesia the use of opioids was omitted until the delivery of baby because of fear of placental transfer and neonatal respiratory depression.

In full term pregnancy, the uterine vasculature is maximally dilated but still respond to vasopressor substance such as catecholamine,[2] which released as a part of stress response during anesthesia and surgery causing uterine vasoconstriction and decrease the utroplacental blood flow[3,4] and adversely affect the neonates.[5] Preventing stress response during intubation and surgery decrease the level of catecholamine and will be beneficial for the mother and neonates.[6]

Nalbuphine hydrochloride is classified as a synthetic opioid agonist-antagonist. It is a potent analgesic and its analgesic potency is essentially equivalent to morphine. It can also be used as a supplement to balanced anesthesia, for preoperative and postoperative analgesia.[7,8]

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of nalbuphine given before induction of general anesthesia for cesarean section on quality of general anesthesia, maternal stress response, and neonatal outcome.

METHODS

This randomized, controlled study was approved by hospital ethics committee and after obtaining written informed consent, the study was carried out in 60 full term pregnant patients scheduled for elective cesarean section American Society of Anaesthesiologist (ASA) I and II.

Inclusion criteria included: Elective full term, single fetus with no signs of fetal distress, and elective cesarean section, while exclusion criteria include emergency situations, fetal distress, multiple gestation, and refusal of patients. The patients were randomly classified into two groups

Group N: Patients received 0.2 mg/kg nalbuphine diluted in 10 ml of normal saline one minute before induction of general anesthesia.

Group C: Patients received placebo 10 ml of normal saline one minute before induction of general anesthesia.

The study used a double-blind design. The patients were randomized into two equal groups. Sixty envelopes were prepared. These envelopes were opened by a blinded chief nurse not participating in the study or patients′ care to indicate the group assignment.

Anesthesia

All patients received 150 mg ranitidine 2 h before induction of anesthesia. After the patients had arrived to operating room, uterine displacement was done by tilting the operating table to the left to decrease aortocaval compression and supine hypotension syndrome. Vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation) were measured and large bore intravenous line was inserted under complete aseptic technique.

Standard patient monitoring (electrocardiogram, non-invasive arterial pressure, heart rate, pulse oximetry and end-tidal CO2) were used during anesthesia. While the patients were prepared for surgery by sterilization of the abdomen and were covered by sterile gowns, preoxygenation was done by allowing the patients to breath 100% O2 for 3 minutes. The patients were randomly classified to receive either 0.2 mg/kg nalbuphine, diluted in 10 ml of normal saline (group N) or control group (group C) received 10 ml saline, which was drawn into an identically labeled syringe.

The study drug was injected one minute before induction of anesthesia. General anesthesia was induced by thiopental 5 mg/kg, succinylcholine 1.5 mg/kg. Endotracheal intubation was done using direct laryngoscope after 30 seconds and anesthesia was maintained by isoflurane 1% in oxygen and atracurium 0.25 mg/kg and artificial ventilation was adjusted to maintain end tidal CO2 around 35 mmHg.

The induction–delivery time and uterine incision-delivery time were recorded. After delivery 0.1 mg/kg morphine were given to control group and same amount of saline to nalbuphine group.

Midazolam 2 mg and 5 units of oxytocine were given as bolus intravenously over 3 minutes for both groups. Oxytocine 10 units in 500 ml ringer solution was infused in both groups to maintain the uterine contraction. After completion of surgery, residual neuromuscular block was antagonized using neostigmine and atropine and the patients was extubated and transported to recovery room.

Maternal measurements

Heart rate and mean arterial blood pressure were measured before induction of anesthesia, five min after intubation, during surgery, and after delivery of baby.

Neonatal outcome measures

This is the job of pediatrician who was unaware of maternal group assignment. The APGAR score at one and five minutes after delivery, and time to sustained respiration was recorded. Umbilical venous and umbilical arterial blood samples were taken for measurement of blood gases. The oxygen saturation, newborn heart rate, and respiratory rate were observed for 6 hours after delivery.

Neonatal resuscitation includes the use of tactile stimulation, oxygen insufflation, bag–mask ventilation, tracheal intubation, and suction.

Naloxone was given if there is sever respiratory depression not responding to neonatal resuscitation including positive pressure ventilation.

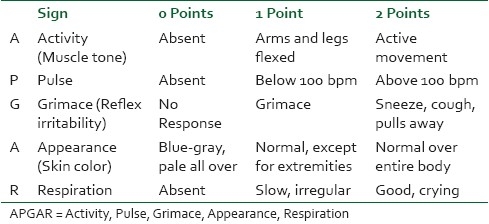

APGAR scoring for newborns [Table 1]

Table 1.

APGAR scoring

The test is generally done at one and five minutes after birth, and may be repeated later if the score is and remains low. Scores ≤3 are generally regarded as critically low, 4 to 6 fairly low, and 7 to 10 generally normal.[9,10]

Statistical analysis

The sample size required for the study was determined based on the primary outcome measure. A power analysis suggested that a sample size of 26 patients per group should be adequate to detect a 20% reduction in blood pressure and heart rate with a power of 0.8 (alpha=0.05). However, to avoid potential errors, 30 patients were included in each group.

All data are summarized as means and standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS program package. Demographic data and blood gas analysis were compared using the unpaired t test. APGAR score was compared using Mann-Whitney U-test. Serial changes in hemodynamic were analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

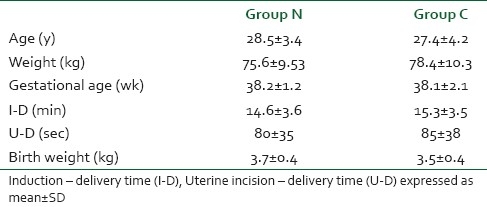

There is no statistically significant difference in age, weight, gestational age, induction delivery time, and uterine incision delivery time and birth weight between the two groups, [Table 2].

Table 2.

Demographic data

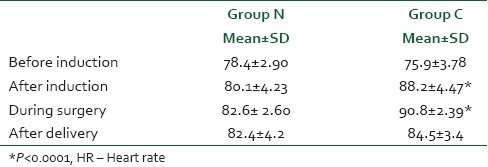

Maternal heart rate changes

There were no differences in base line heart rate in two groups. Maternal heart rate showed significant increase in control group than nalbuphine group after intubation (88.2±4.47 versus 80.1±4.23, P<0.0001) and during surgery till delivery of baby (90.8±2.39 versus 82.6±2.60, P<0.0001) and no significant changes between both groups after delivery. After delivery and giving opioid to control group, the heart rate (HR) was decreased and there were no significant differences in HR till the recovery of patients, [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of maternal HR changes in both groups

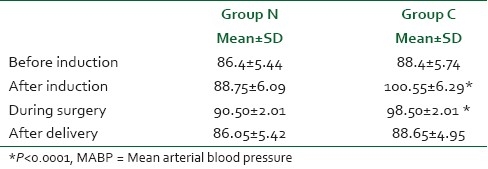

Maternal mean arterial blood pressure changes

There were no differences in base line mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) in two groups. The maternal MABP increased in control group than nalbuphine group after intubation (100.55±6.29 versus 88.75±6.09, P<0.0001) and during surgery till delivery of baby (98.50±2.01 versus 90.50±2.01, P<0.0001) and no significant changes between both groups after delivery. After delivery and giving opioid to control group, the MABP was decreased and there were no significant differences in MABP till the recovery of patients, [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of maternal MABP changes in both groups

Neonatal outcome

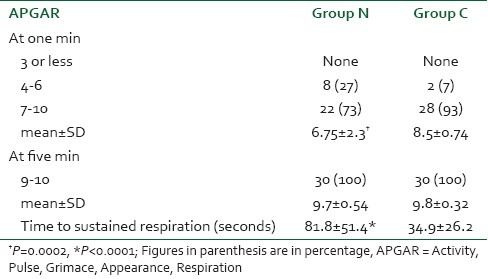

APGAR score was recorded one and five minutes after delivery. APGAR score was significantly low in nalbuphine group than control group at one minute (mean score in nalbuphine group was 6.75±2.3 and in control group was 8.5±0.74, P=0.0002), [Table 5].

Table 5.

APGAR score in both groups

At one minutes after delivery eight neonates (27%) in nalbuphine group and two neonates (7%) in group C showed APGAR score ranged from 4–6, while 22 neonates (73%) in group N and 28 neonates (93%) in group C showed APGAR score ranged between 7–10.

At five minutes, all neonates in both groups showed APGAR score 9–10, [Table 5].

Neonates in both groups with APGAR score less than 6 required short period of assisted ventilation by ambou bag with mask connected to source of oxygen until the respiration was sustained.

The mean time to sustained respiration in group N was significantly longer (81.8±51.4 s) than in group C (34.9±26.2 s), P<0.05 [Table 5].

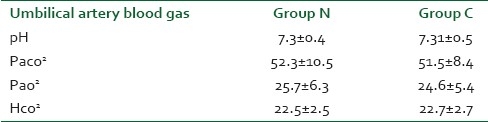

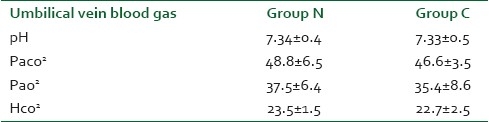

Neonatal blood gas in both groups (arterial and venous) showed no significant differences in both groups, [Tables 6 and 7].

Table 6.

Umbilical cord artery blood gas analysis at delivery expressed as mean±SD

Table 7.

Umbilical cord vein blood gas analysis at delivery expressed as mean±SD

DISCUSSION

Stress response to intubation and surgery with subsequent increase in catecholamines level have adverse effect on mother and also may adversely affect the fetus.[11] So, preventing the stress response will be better for both mother and neonates.

Nalbuphine was studied extensively in labor analgesia and was proved to be acceptable analgesics during delivery and its effect on neonates vary between studies, but its use as a premedication before induction of general anesthesia for cesarean section had not been studied. In the present study, the maternal blood pressure and heart rate were increased significantly in control group than nalbuphine group after induction of anesthesia till delivery of baby.

APGAR score was lower in the nalbuphine group, and this was probably a result of the placental transfer of nalbuphine which the only factor contributes for neonatal depression as the induction delivery time and uterine incision delivery time was comparable in both groups.

Nalbuphine pass through the placenta rapidly[12,13] and the elimination half-life of nalbuphine in neonates is 4.1 hours,[14] which was shorter than that of meperidine in neonates 7-32 hours.[15] So, the neonatal effects of nalbuphine will be of shorter duration than meperidine.

Wilson et al.,[12] found that when nalbuphine was used as bolus for maternal analgesia during labor it was associated with decreased APGAR and neonatal neurobehavioral scores compared to bolus meperidine, but others studies did not find any significant effect of nalbuphine on neonatal outcome.[16–18]

These studies examined using nalbuphine for labor analgesia and only one study published in 1985 by Dadabhoy et al.,[13] in which nalbuphine was used after intubation and revealed that it maintained maternal hemodynamics stability with acceptable neonatal APGAR score and no correlation was observed between neonatal blood levels and APGAR scores.

Many published studies had used different opioids like alfentanil,[19] fentanyl,[20] and remi fentanyl[21] before induction of anesthesia for elective cesarean section. The result of these studies is as follows: In alfentanil study, alfentanil 10 μg/kg was given 1 minute before induction of anesthesia; and maternal stress response was attenuated in the alfentanil group but at the cost of early neonatal depression. In fentanyl study, maternal analgesia and sedation with fentanyl (1 μg/kg) and midazolam (0.02 mg/kg) given immediately prior to spi-nal anesthesia is not associated with adverse neonatal effects and in remifentanil study, single bolus of 1 μg/kg remifentanil given immediately before induction of general anesthesia was effectively attenuated hemodynamic changes after induction and tracheal intubation. However, remifentanil crosses the placenta and may cause mild neonatal depression.

In a study done by Nicolle et al.[14] to delineate placental transfer and disposition of nalbuphine in the neonate found that nalbuphine placental transfer is high and estimated half life of nalbuphine in neonate is longer than in adult and two neonates had low APGAR score at one minutes and one of them had score of 8, which improved spontaneously to 10 at 5 min and the other had score 3 and improved to 10 after resuscitation.

CONCLUSION

Administration of nalbuphine before cesarean section under general anesthesia reduces maternal stress response related to intubation and surgery, but decreases the APGAR score at one minute after delivery. So, when nalbuphine was used, all measures for neonatal monitoring and resuscitation must be available including attendance of a pediatrician.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roy JE, Leslie SP. The Anesthetic Cascade: A Theory of How Anesthesia Suppresses Consciousness. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:447–71. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200502000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velly LJ, Rey MF, Bruder NJ, Gouvitsos FA, Witjas T, Regis JM, et al. Differential Dynamic of Action on Cortical and Subcortical Structures of Anesthetic Agents during Induction of Anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:202–12. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270734.99298.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenfeld CR, Barton MD, Meschia G. Effects of epinephrine on distribution of blood flow in the pregnant ewe. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;124:156–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)33292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shnider SM, Wright RG, Levinson G, Roizen MF, Wallis KL, Rolbin SH, et al. Uterine blood flow and plasma norepinephrine changes during maternal stress in the pregnant ewe. Anesthesiology. 1979;50:524–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197906000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nandi PR, Morrison PJ, Morgan BM. Effects of general anaesthesia on the fetus during Caesarean section. In: Kaufman L, editor. Anaesthesia review 8. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston; 1991. pp. 103–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gin T, O’Meara ME, Kan AF, Leung RK, Tan P, Yau G. Plasma catecholamines and neonatal condition after induction of anaesthesia with propofol or thiopentone at Caesarean section. Br J Anaesth. 1993;70:311–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/70.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Errick JK, Heel RC. Nalbuphine: A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1983;226:191–211. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198326030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guignard B. Monitoring analgesia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2006;20:161–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finster M, Wood M. The APGAR score has survived the test of time. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:855–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200504000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casey BM, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. The continuing value of the APGAR score for the assessment of newborn infants. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:467–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Littleford J. Effects on the fetus and newborn of maternal analgesia and anesthesia: A review. Can J Anesth. 2004;51(6):586–609. doi: 10.1007/BF03018403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson SJ, Errick JK, Balkon J. Pharmacokinetics of nalbuphine during parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:340–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90822-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dadabhoy ZP, Tapia DP, Zsigmond EK. Transplacental transfer of nalbuphine in patients undergoing Cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1985;64:205. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicolle E, Devillier P, Delanoy B, Durand C, Bessard G. Therapeutic monitoring of nalbuphine: Transplacental transfer and estimated pharmacokinetics in the neonate. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;49:485–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00195935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morselli PL, Rovei V. Placental transfer of pethidine and norpethidine and their pharmacokinetics in the newborn. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;18:25–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00561475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wahab SA, Askalani AH, Amar RA, Ramadan ME, Neweigy SB, Saleh AA. Effect of some recent analgesics on labor pain and maternal and fetal blood gases and pH. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1988;26:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(88)90199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank M, McAteer EJ, Cattermole R, Loughnan B, Stafford LB, Hitchcock AM. Nalbuphine for obstetric analgesia.A comparison of nalbuphine with pethidine for pain relief in labour when administered by patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) Anaesthesia. 1987;42:697–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1987.tb05313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Podlas J, Breland BB. Patient-controlled analgesia with nalbuphine during labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:202–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tony G, Warwick D, Ngan K, Yuk K, Joyce C, Perpetua E, et al. Alfentanil given immediately before the induction of anesthesia for elective cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:1167–72. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200005000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michael A, David J, Tammy Y, Donald C. A single dose of fentanyl and midazolam prior to Cesarean section have no adverse neontal effects. Can J Anesth. 2006;53:79–85. doi: 10.1007/BF03021531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Draisci G, Valente A, Suppa E, Frassanito L, Pinto R, Meo F, et al. Remifentanil for cesarean section under general anesthesia: Effects on maternal stress hormone secretion and neonatal well-being: A randomized trial. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2008;17:130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]