Abstract

Objectives:

Spontaneous reporting is an important tool in pharmacovigilance. However, its success depends on cooperative and motivated prescribers. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) by prescribers is a common problem. The present study was undertaken to evaluate the knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) regarding ADR reporting among prescribers at the Civil Hospital, Ahmedabad, to get an insight into the causes of under-reporting of ADRs.

Materials and Methods:

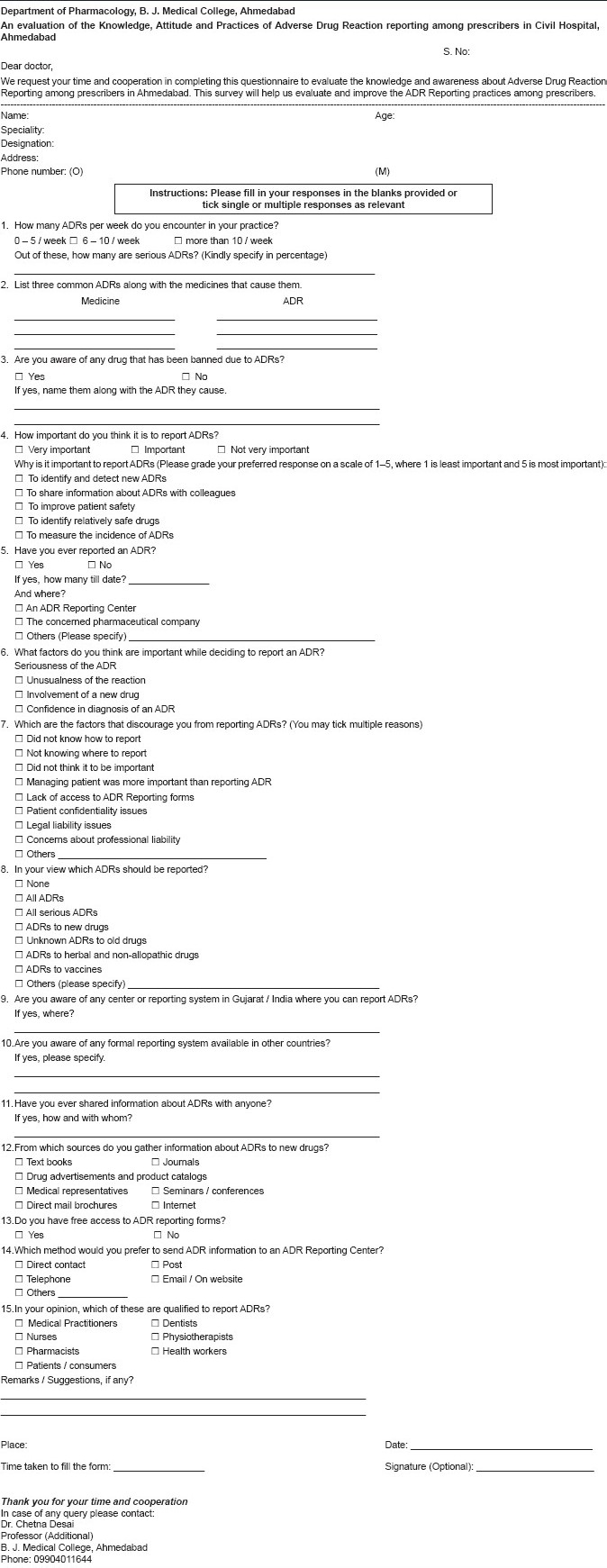

A pretested KAP questionnaire comprising of 15 questions (knowledge 6, attitude 5, and practice 4) was administered to 436 prescribers. The questionnaires were assessed for their completeness (maximum score 20) and the type of responses regarding ADR reporting. Microsoft Excel worksheet (Microsoft Office 2007) and Chi-Square test were used for statistical analysis.

Results:

A total of 260 (61%) prescribers completed the questionnaire (mean score of completion 18.04). The response rate of resident doctors (70.7%) was better than consultants (34.5%) (P < 0.001). ADR reporting was considered important by 97.3% of the respondents; primarily for improving patient safety (28.8%) and identifying new ADRs (24.6%). A majority of the respondents opined that they would like to report serious ADRs (56%). However, only 15% of the prescribers had reported ADRs previously. The reasons cited for this were lack of information on where (70%) and how (68%) to report and the lack of access to reporting forms (49.2%). Preferred methods for reporting were e-mail (56%) and personal communication (42%).

Conclusion:

The prescribers are aware of the ADRs and the importance of their reporting. However, under reporting and lack of knowledge about the reporting system are clearly evident. Creating awareness about ADR reporting and devising means to make it easy and convenient may aid in improving spontaneous reporting.

Keywords: Adverse drug reaction, knowledge, attitude, and practices study, pharmacovigilance, spontaneous reporting

INTRODUCTION

Introduction of newer medicines has changed the way in which diseases are treated. However, it is not without risks. Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are encountered commonly in daily practice, many of which are preventable.[1,2] A study carried out in south India by Ramesh et al. observed that 0.7% of hospital admissions were due to ADRs and a total of 3.7% of the hospitalized patients experienced an ADR, of which 1.3% were fatal.[3] Another study by Arulumani et al. showed that ADRs were responsible for 3.4% of the hospital admissions and 3.7% developed ADRs during their hospital stay.[4] The incidence of serious ADRs is 6.7% in India.[5] In addition to the obvious morbidity and mortality caused by them, ADRs are also an economic burden on the healthcare system.[6,7] Hence, their early detection and prevention is necessary.

Monitoring of ADRs is carried out by various methods, of which voluntary or spontaneous reporting is commonly practised. This system offers many advantages. It is inexpensive and easy to operate. It encompasses all drugs and patient populations, including special groups. However, under-reporting and an inability to calculate the incidence of ADRs are the inherent disadvantages of this method.[8–10] In order to improve the participation of health professionals in spontaneous reporting, it might be necessary to design strategies that modify both the intrinsic (knowledge, attitude and practices) and extrinsic (relationship between health professionals and their patients, the health system and the regulators) factors. A knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) analysis may provide an insight into the intrinsic factors and help understand the reasons for under-reporting.

Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding ADR reporting has not been studied extensively in India. A few studies carried out in India and Nepal have shown poor knowledge, attitude, and deficient practices of ADR reporting among the prescribers and healthcare professionals.[11–13] Spontaneous reporting by prescribers at the Civil Hospital, Ahmedabad (CHA), began in June 2005, through the initiatives taken at the Peripheral Reporting Center of the National Pharmacovigilance Program (NPVP) at the Department of Pharmacology, B. J. Medical College, Ahmedabad. Having sensitized these prescribers to spontaneous reporting, it was thought worthwhile to assess the KAP regarding ADR reporting of these professionals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional, observational, questionnaire-based study, conducted at CHA, a 2000 - bedded tertiary care teaching hospital, with an out-patient turnover of 0.75 million and in-patient turnover of 70,000 annually. As this was a non-interventional study among the prescribers of the Civil Hospital Ahmedabad, prior approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Medical Superintendent of the Hospital.

Prescribers (faculty consultants and postgraduate students or residents) from all specialties working in the hospital were enrolled in the study after obtaining an informed consent. Those who were not willing to participate or did not return the questionnaire within the stipulated time were excluded. A KAP questionnaire containing 15 questions (knowledge 6, attitude 5, and practice 4) was designed using the precedence set by similar studies,[13–15] to obtain information regarding the demographics of the respondents, knowledge regarding the ADR reporting system, attitude and practice of ADR reporting, and the factors that encouraged and discouraged reporting. Four questions were open ended, while the others were close ended. The questionnaire was designed in such a way that the answers were not mutually exclusive. More than one answer was allowed in some questions [Annexure 1]. The questionnaire was pre-tested in ten postgraduate students and ten faculties and a suitably modified version was finally administered to the willing respondents, who were requested to return them within two weeks. Reminders were sent after a week and if the questionnaires were misplaced, they were replaced. The participants were personally briefed about the study questionnaire and were requested to record the time taken to complete it.

Annexure 1.

The questionnaires were evaluated for their completeness, and completeness scores were assigned as pre-decided (maximum score: 20). One point was given to each answered question (15 points) and the remaining five points were allotted for the demographic information (3 points), suggestions given (1 point), and one point was allotted for completing the concluding information. The knowledge of the respondents was also scored (out of 17) as per their responses to questions 2, 3, 9, 10, 13, and 15. The information was recorded and analyzed using the Microsoft Excel worksheet (Microsoft Office 2007) and the Chi-Square test. P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

The questionnaire was administered to 426 prescribers, of whom 139 were faculty consultants and 287 were postgraduate students (resident doctors). A total of 260 questionnaires were returned, giving a response rate of 61%. The average time taken to complete the questionnaire was 11 minutes and the mean score of completeness of the questionnaire was 18.04 out of 20. Of the total respondents (260), 18.5% were faculty members, while the rest were postgraduate students. The response rate of postgraduate students (70.7%) was significantly higher than that of faculty members (34.5%) (P < 0.001). Even as the attitude and practice of the respondents was not quantified, an attempt was made to quantify the knowledge of the respondents. It was calculated by assessing the responses to certain questions. A maximum score of 3 was assigned to question 2, while a maximum score of 2 was assigned to questions 3, 9, and 10. Questions 13 and 15 were assigned a maximum score of 1 and 7, respectively. One point was given for each correct option. Using this scoring system, it was observed that the overall mean score of the knowledge of the respondents was 6.46 (38.2%), and faculty and postgraduate students scored 7.27 (42.7%) and 6.28 (36.9%), respectively.

A total of 221 respondents out of 260 (85%) stated that they encountered up to five ADRs / week. One hundred and sixteen respondents (44.6%) mentioned that up to 10% of the ADRs they encountered were serious. The common drug groups observed to cause ADRs were antimicrobials (41.6%) and analgesics (15.9%). The common ADRs observed were cutaneous (35.7%) (which included rashes, urticaria, anaphylaxis, and SJ syndrome) followed by gastrointestinal adverse effects (27.7%) (which included nausea, vomiting, gastritis, and diarrhea).

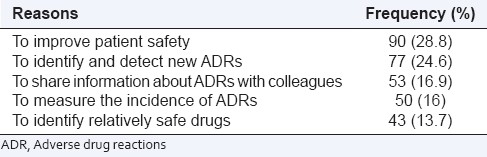

Adverse drug reaction reporting was considered to be important by 97.3% of the respondents. The need to improve patient safety (28.8%) and the detection of new ADRs (24.6%) were the common reasons cited for reporting ADRs [Table 1]. Thirty-nine (15%) respondents said that they had reported an ADR previously. The ADRs were usually reported to an ADR reporting center (41%), pharmaceutical companies (33.3%), presented at conferences, or published in journals (15.4%).

Table 1.

Reasons cited by prescribers for reporting ADRs (n = 260)

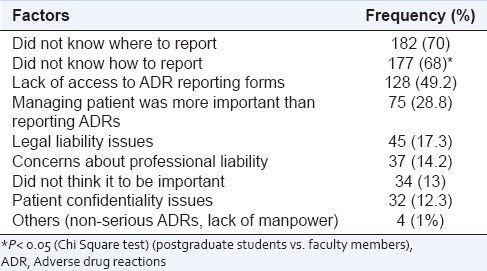

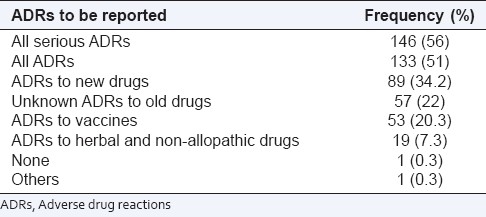

The reasons cited by prescribers for not reporting ADRs are listed in Table 2. Lack of knowledge on how (68%) and where (70%) to report the ADRs and lack of easy access to ADR reporting forms (49.2%) were the major factors that discouraged reporting. Although both groups of respondents cited similar reasons for not reporting ADRs, a greater percentage of residents responded that they did not report ADRs because they did not know how to do it (P = 0.02) [Table 2]. However, both groups had similar views on which ADRs should be reported, with a preference for serious ADRs. Fifty-one percent of the respondents stated that they would like to report all ADRs, while 56% said that they would like to report only serious ADRs. As against this, 34.2% said they would report ADRs caused by new drugs. Most respondents, however, did not emphasize on reporting ADRs to herbal and non-allopathic medicines [Table 3].

Table 2.

Factors that may discourage prescribers from reporting ADRs (n = 260)

Table 3.

Prescribers’ opinion on which ADRs should be reported (n = 260)

The respondents were tested for their awareness about the ADR reporting center. Twenty-five of them were aware that ADRs could be reported to the Peripheral Center, National Pharmacovigilance Program, at the Department of Pharmacology, B. J. Medical College, Ahmedabad. Seven respondents were aware of other ADR reporting systems worldwide.

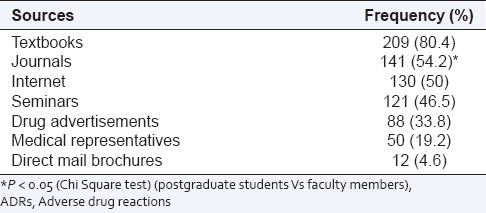

A total of 101 (38.8%) respondents said that they shared information about ADRs observed by them, mostly with their colleagues and teachers. Textbooks (80.4%) and scientific journals (54.2%) were the preferred sources from which the respondents updated their knowledge regarding ADRs of new drugs, followed by the Internet (50%), seminars (46.5%), and drug advertisements (33.8%). A greater number of faculty referred to scientific journals as a source of information about ADRs of new drugs, as compared to the residents (P = 0.002). It was however evident that most respondents relied on multiple sources of information for their knowledge about ADRs [Table 4]. A majority of the respondents felt that they, as medical practitioners (92.3%) were qualified to report ADRs. Dentists (41.2%), nurses (34.2%), and pharmacists (34.2%) were also considered qualified for reporting ADRs. Interestingly about 26.2% of the respondents opined that patients should also be allowed to report ADRs. Opinion was sought from the respondents about their preferred mode of reporting. Electronic media like e-mails or websites (56%) and reporting by a personal communication to the reporting center (42%) were the methods preferred by most respondents.

Table 4.

Source of information about ADRs of new drugs (n = 260)

Several measures were suggested for improving ADR reporting. These included creating awareness about ADR monitoring among the healthcare personnel and consumers, through appropriate educational interventions, making ADR reporting forms easily accessible, and simplifying the process of reporting. Feedback provided to the reporters about the causality of ADRs reported by them would also encourage them to continue reporting. It was also suggested that pharmacologist(s) from the institute should be posted in clinical wards to promote and assist in the reporting and management of ADRs.

DISCUSSION

The present study was a questionnaire-based study, which included all prescribers of a tertiary care teaching hospital. This preliminary study showed that while the right attitude for ADR reporting existed among most prescribers, the actual practice of ADR reporting was lacking. Indian studies at Mumbai,[12], Mysore,[14] and Muzzafarnagar[15] have shown high knowledge, but poor practice for ADR, among prescribers. In contrast our study has found not only poor practice, but also inadequate knowledge regarding ADR reporting. The average knowledge score of the respondents was 38%, indicating that there is still much to be done to educate the prescribers regarding ADR reporting.

The percentage of completed response (61%) was found to be similar to studies carried out in Germany,[16] northern Italy,[10] and United Kingdom,[17] but lower than Nigeria,[18] Netherlands,[19] and northern region of England.[20] This study shows that the postgraduate students (70.7%) responded significantly more than the faculty members (34.5%) (P < 0.001). This may be because these students are easily accessible and on call 24 hours, as against the faculty members who are present in the hospital only during the office hours. This, however, does not undermine the importance of the latter group for future interventions, to improve spontaneous reporting as the senior faculty can influence the ADR reporting behavior of their residents on a continuous and long-term basis.

A majority of the prescribers had observed up to five ADRs a week. This was a positive reflection on the clinical skills and awareness about ADRs among the prescribers. Around half of the respondents reported that up to 10% of the ADRs observed were of a serious nature. However, the actual practice of reporting ADRs was different than the knowledge and attitudes exhibited by the respondents.

Even as ADR reporting was considered to be important by a large majority of the respondents, the actual reporting was very low. Just 15% of the respondents stated that they had reported an ADR previously. Similarly, the Mumbai study[12] also cited similar findings of under-reporting of ADR to any of the national ADR monitoring centers (2.9%) in spite of 90% of the respondents considering it important. The reasons for reporting ADRs, as reported by Biriell and Edwards,[21] are, a desire to contribute to medical knowledge, identifying a previously unknown ADR, reactions to new drugs, and severity of the ADR. In our study too, the reasons for reporting, as cited by a majority of the respondents of both groups, were, improving the safety of the patients and identifying new ADRs.

In this study, of the 39 respondents who had reported an ADR previously, 16 had reported to an ADR reporting center, 13 to the concerned pharmaceutical company, while six had reported them at conferences or in journals. ADRs reported to pharmaceutical companies were part of a clinical trial protocol or as a personal interaction with the respective medical representatives.

The reasons for under-reporting of ADRs have been summarized by Inman[22] as the “seven deadly sins”. This includes financial incentives (rewards for reporting), legal aspects (fear of litigation), complacency (belief that the serious ADRs are already documented when a drug is introduced in the market), diffidence (belief that reporting should be done when there is certainty that the reaction is caused by the use of a particular drug), indifference (belief that a single report would make no difference), ignorance (that only serious ADRs are to be reported), lethargy (excuses about lack of time or disinterestedness). Some of these sins were also documented in Mysore,[14] Mumbai,[12] and Muzaffarnagar[15] (complacency, ignorance, lethargy). In our study a major reason observed was ignorance about the reporting system, which was also seen in the study conducted in Mumbai,[12] while the financial and legal aspects were given less importance. Ignorance was more evident in the residents as compared to the faculty. This suggests that an intervention to generate awareness on how to report ADRs may be necessary for this group of respondents. An interesting observation was that 13% of the respondents did not think that reporting ADRs was important. The observations were similar to a study done in a teaching hospital in Spain, where the potential obstacles to spontaneous reporting of ADRs were identified to be difficulty in diagnosis of ADRs, lack of knowledge regarding the ADR reporting system, clinical workload on the doctors, a concern for patient confidentiality, and possible legal implications of reporting.[23]

More than half of the respondents opined that they would report all the ADRs observed by them. This was similar to the responses obtained in a study done in northern Italy,[10] where the doctors considered all suspected reactions to any marketed drug and all serious suspected ADRs as worth reporting. On the other hand, in a study done in Nigeria[18] and Mumbai,[12] the respondents would mainly report ADRs to either new drugs or serious ADRs to established drugs.

Few respondents could identify B.J. Medical College as an ADR reporting center in Gujarat (under the older National Pharmacovigilance Program of India) and only 3% could identify any reporting system in the world. This was intriguing, considering the fact that the prescribers at this institution have been reporting ADRs for last five years to this Center and have reported 1740 ADRs to date. Further analysis into the reasons for this response is warranted. This does, however, suggest that periodic feedback and continuous sensitization to the existing pharmacovigilance system and ADR reporting is necessary, so that the interest and awareness of the prescribers do not wane. However, it was different at Mumbai[12] and Mysore[14] where nearly 50 and 89% of the respondents, respectively, knew about the reporting center at their college. Regarding the source of information about ADRs to new drugs, it was observed that the faculty used scientific journals as their source for knowledge about ADRs to new drugs, which was significantly higher than the residents who depended on text books for this information (P < 0.05).

Spontaneous reporting of ADRs by patients and healthcare personnel, other than doctors, is practiced in many parts of the world.[24–26] This was not recognized by the respondents in our study, as less than half identified nurses, pharmacists, and dentists to be capable of reporting ADRs. These findings were also observed in the Mumbai study where respondents did not identify nurses and pharmacists as qualified reporters. This again indicates a lack of awareness of the principles and practice of pharmacovigilance among the respondents.

The suggestions given by the respondents to improve ADR reporting corresponded with those observed in other studies. In a study carried out in Nigeria,[18] imparting continuous medical education, training, encouraging feedback from patients, prescribers and dispensers, publicity of a reporting scheme in local journals, and appointing an ADR specialist in every hospital, were some of the suggestions put forward by the prescribers for improving reporting. It was also opined that reporting of serious ADRs should be prioritized considering the workload of the prescribers. Also reporting should be made easy and convenient (by post or email / websites, etc.). These measures could improve the quantum and quality of the reports.

In conclusion, under-reporting of ADRs can be due to various reasons. A KAP study has certain limitations[27] and it would be inappropriate to plan interventions based on the findings of this study alone. However, this study does provide an insight into the possible interventions that could be planned in future. This study has just scratched underneath the surface by identifying the KAP of ADR reporting among prescribers and reasons for under-reporting. The deficits in the practice of ADR reporting can be resolved only if the prescribers are aware of the importance of reporting, the reporting system, and their obligation to report ADRs. With an ADR reporting system in place at the institution, one needs to go a step forward and implement these suggestions for strengthening the existing spontaneous ADR reporting system. Educational interventions, acknowledgment, feedback to reporters about the ADRs reported by them, and professional support offered to the prescribers, by a pharmacologist, in reporting and managing ADRs, would help achieve this. Widening the reporter base by extending it to nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals would also help strengthen ADR reporting.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McDonnell PJ, Jacobs MR. Hospital admissions resulting from preventable adverse drug reactions. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1331–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, Peterson LA, Small SD, Servi D, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. J Am Med Assoc. 1995;274:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramesh M, Pandit J, Parthasarathi G. Adverse drug reactions in a south Indian hospital-their severity and cost involved. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12:687–92. doi: 10.1002/pds.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arulmani R, Rajendran SD, Suresh B. Adverse drug reaction monitoring in a secondary care hospital in South India. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;65:210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02993.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Importance of ADR reporting in India. [Last cited on 2011 Mar 15]. Available from: http: / / www.pharmacovigilance.co.in / whyadrreporting.html .

- 6.Wasserfallen JB, Livio F, Buclin T, Tillet L, Yersin B, Biollaz J. Rate, type and cost of adverse drug reactions in emergency department admissions. Eur J Intern Med. 2001;12:442–7. doi: 10.1016/s0953-6205(01)00159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goettler M, Schneeweiss S, Hasford J. Adverse drug reaction monitoring—cost and benefit considerations. Part II: Cost and preventability of adverse drug reactions leading to hospital admission. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1997;6(Suppl 3):S79–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1557(199710)6:3+<s79::aid-pds294>3.3.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montastruc JL, Sommet A, Lacroix I, Olivier P, Durrieu G, Damase-Michel C, et al. Pharmacovigilance for evaluating adverse drug reactions: Value, organization, and methods. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:629–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: Definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet. 2000;356:1255–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02799-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosentino M, Leoni O, Banfi F, Lecchini S, Frigo G. Attitudes to adverse drug reaction reporting by medical practitioners in a Northern Italian district. Pharmacol Res. 1997;35:85–8. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1996.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rehan HS, Vasudev K, Tripathi CD. Adverse drug reaction monitoring: Knowledge, attitude and practices of medical students and prescribers. Natl Med J India. 2002;15:24–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta P, Udupa A. Adverse drug reaction reporting and pharmacovigilance: Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions among resident doctors. J Pharm Sci Res. 2011;3:1064–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subish P, Izham MM, Mishra P. Evaluation of the knowledge, attitude and practices on adverse drug reactions and pharmacovigilance among healthcare professionals in a Nepalese hospital: A preliminary study. Internet J Pharmacol. 2008;6:1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramesh M, Parthasarathi G. Adverse drug reactions reporting: attitudes and perceptions of medical practitioners. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2009;2:10–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh S, Ali S, Chhabra L, Prasad C, Gupta A. Investigation of attitudes and perception of medical practitioners on adverse drug reaction reporting – a pilot study. T Ph Res. 2010;3:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasford J, Goettler M, Munter KH, Muller-Oerlinghausen Physician's knowledge and attitudes regarding the spontaneous reporting system for adverse drug reactions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;55:945–50. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eland IA, Belton KJ, van Grootheest AC, Meiners AP, Rawlins MD, Stricker BH. Attitudinal survey of voluntary reporting of adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48:623–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oshikoya KA, Awobusuyi JO. Perceptions of doctors to adverse drug reaction reporting in a teaching hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2009;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belton KJ, Lewis SC, Payne S, Rawlins MD, Wood SM. Attitudinal survey of adverse drug reaction reporting by medical practitioners in the United Kingdom. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;39:223–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb04440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bateman DN, Sander GL, Rawlins MD. Attitudes to adverse drug reaction reporting in the Northern Region. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;34:421–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biriell C, Edwards IR. Reasons for reporting ADR – some thoughts based on an international review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1997;6:21–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1557(199701)6:1<21::AID-PDS259>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inman WH. Attitudes to adverse drug-reaction reporting. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;41:433–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallano A, Cereza G, Pedròs C, Agustí A, Danés I, Aguilera C, et al. Obstacles and solutions for spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions in a hospital. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:653–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Grootheest AC, van Puijenbroek EP, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Contribution of pharmacists to the reporting of adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:205–10. doi: 10.1002/pds.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Langen J, van Hunsel F, Passier A, de Jong-van den Berg LT, van Grootheest K. Adverse drug reaction reporting by patients in the Netherlands.Three years of experience. Drug Saf. 2008;31:515–24. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrison-Griffiths S, Walley TJ, Park BK, Breckenridge AM, Pirmohamed M. Reporting of adverse drug reactions by nurses. Lancet. 2003;361:1347–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Launiala A. How much can a KAP survey tell us about people's knowledge, attitudes and practices? Some observations from medical anthropology research on malaria in pregnancy in Malawi. Anthropol Matters. 2009;11:1–13. [Google Scholar]