Abstract

Growing evidence over the last few years suggests a central role of type I IFN pathway in the pathogenesis of systemic autoimmune disorders. Data from clinical and genetic studies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and lupus-prone mouse models, indicates that the type I interferon system may play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of several lupus and associated clinical features, such as nephritis, neuropsychiatric and cutaneous lupus, premature atherosclerosis as well as lupus-specific autoantibodies particularly against ribonucleoproteins. In the current paper, our aim is to summarize the latest findings supporting the association of type I IFN pathway with specific clinical manifestations in the setting of SLE providing insights on the potential use of type I IFN as a therapeutic target.

1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the prototype of systemic autoimmune disorders, affecting virtually any organ system of mainly young women of child-bearing age, at an incidence ranging from 2 to 5 cases per 100,000 persons. It is characterized by remarkable heterogeneity in regard to the spectrum and severity of clinical and laboratory manifestations, with disease activity fluctuating considerably during the course of the disease. While genetic susceptibility along with environmental interactions contributes significantly to the immune dysregulation that characterizes SLE, the exact etiopathogenesis remains elusive [1].

In the late 1970s, increased serum levels of interferon (IFN) were shown for the first time to be significantly associated with SLE and to correlate with disease activity [2]. Later reports showing that chronic treatment with recombinant IFNα in patients affected with malignancies induces autoimmune manifestations [3] coupled by subsequent studies documenting heightened serum levels of type I IFN and type I IFN-inducible genes [4] in patients with SLE reinforced the hypothesis that type I IFN has a major role in the pathogenesis of SLE. Although the exact triggers of type I IFN activation in SLE are unknown, exogenous viral agents or endogenous nucleic acids seem to be potential candidates through sensing of pattern recognition membrane and cytosolic receptors of specialized IFNα-producing cells such as plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), while genetic contributors in generation of type I IFN in SLE have been also implicated [5]. Of note, recent data have shown that mature neutrophils from lupus patients undergo apoptosis upon exposure to SLE-derived anti-ribonucleoprotein antibodies releasing neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) that contain DNA and neutrophil-derived proteins. The SLE NETs efficiently activate the pDCs to produce type I IFNs, thus, acting as an endogenous stimulus for the type I IFN pathway [6, 7].

In the current paper, our aim is to summarize the latest findings previously shown to support the association of type I IFN pathway with specific clinical manifestations of SLE particularly those characterized by renal, skin, neurological involvement, as well as concomitant atherosclerosis providing insights on the potential use of type I IFN as a biomarker and/or therapeutic target in these patients. To the best of our knowledge, no data to date support the association of type I IFN activation with other lupus-related manifestations such as serositis or arthritis.

2. Type I IFN and Lupus Nephritis

Lupus nephritis and the progression to end-stage renal disease represent one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in SLE patients. Almost half of the patients with SLE present with clinical lupus nephritis, and up to 90% of patients have some degree of histological renal damage. Different interacting pathogenetic mechanisms such as immune complex deposition, renal infiltration by T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells, activation of toll-like receptors (TLRs), and a variety of cytokines as well as end-organ responses to immune injury contribute to the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis [15].

Despite data deriving both from murine lupus models and patients with SLE supporting a pathogenetic role for type II IFN (IFNγ), there is ever increasing evidence indicating type I IFNs as one of the major players in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. In 1979, Hooks et al. noticed for the first time a significant association of type I IFN serum levels with active lupus [2]. Two years later, Rich reported that typical lupus inclusions (detected in the glomerular endothelium in almost all lupus patients and in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of more than two-thirds) were induced by type I IFN in the Raji cells, a human B-lymphoblastoid cell line of Burkitts lymphoma origin [16]. Since then, several studies in patients with SLE have demonstrated a significant association between both type I IFN serum levels and IFN-induced gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)—the so-called interferon signature—[2, 8–14] with disease activity and other disease-related features including lupus nephritis (Table 1). It should be noted that the largest so far study performed by Weckerle et al., which included 1089 patients from 3 different ancestral backgrounds, showed a strong association between certain autoantibodies and high IFNα activity but failed to detect significant association with clinical features of the disease. However, disease activity was not assessed in this study. In addition to the aforementioned studies associating type I IFN and clinical and serological features of SLE, cDNA microarray analysis of gene expression in glomeruli, isolated by laser-capture microscopy from kidney biopsies of lupus patients with focal/diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis, revealed increased expression of type I IFN-inducible genes, thus, implying a possible pathogenetic role for type I IFN in these patients [17]. Glomerular expression of TLR-9, an endosomal sensor of CpG DNA leading to type I IFN production, was reported in patients with lupus nephritis but not in healthy controls and was associated with anti-dsDNA and higher activity index of lupus nephritis [18].

Table 1.

Studies in patients with SLE showing statistical significant associations (P < 0.05) between peripheral type I IFN activity and clinical and serological features.

| Author | No. of patients | Type I IFN levels | Type I IFN-inducible genes | Clinical associations | Serological associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hooks et al. [2] | 28 | High | NM | Disease activity | Anti-dsDNA Low C3 |

| Kanayama et al. [8] | 25 | High | NM | Fever | NM |

| Bengtsson et al. [9] | 30 | High | NM | Disease activity Fever Skin |

Anti-dsDNA Low C1q Low C3 Leucopenia |

| Baechler et al. [10] | 48 | NM | High | Renal and/or NPSLE Hematologic | NM |

| Dall'era et al. [11] | 65 | High | NM | Disease activity Skin |

Anti-dsDNA Low C3 |

| Kirou et al. [12] | 77 | NM | High | Renal | Anti-dsDNA Anti-Ro Anti-U1 RNP Anti-Sm Low C3 Low C4 |

| Feng et al. [13] | 48 | NM | High | Renal NPSLE (weak association) |

Anti-dsDNA Anti-Sm Anti-Ro/La Low C3 |

| Weckerle et al. [14] | 1089 | High | NM | NS | Anti-dsDNA Anti-Ro |

NM: not measured, NS: not statistically significant. All abbreviations are explained in the text.

Moreover, recent genetic association studies have identified many lupus-associated genetic variants in genes encoding transcription factors and various molecular components involved in the type I IFN pathway [19–37]. Studies investigating a possible association between genotype and phenotype in lupus patients have brought to light conflicting results regarding the association with lupus nephritis. A case-control study by Taylor et al. in a large cohort of North American patients of European descent showed a significant association between the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs7574865 of the STAT4 gene and lupus nephritis, anti-dsDNA and early disease onset [38]. Accordingly, SNPs of the STAT4 gene was associated with lupus nephritis and anti-dsDNA in a cohort of 695 Swedish patients [24]. Similar results, although not statistically significant probably due to small sample size, were reported in a Japanese study for the SNP rs7574865 of STAT4 gene [39]. In contrast, the same SNP of STAT4 was not associated with any specific clinical manifestation of lupus in a Northern Han Chinese case-control study. This may be attributed to differences in immune pathways influenced by this polymorphism among different populations. An alternative explanation could derive from the fact that rs7574865 with nearby SNPs can form different haplotype blocks each one conferring a distinct risk for SLE and for specific SLE manifestations. Therefore, the diverse effect of this risk SNP in SLE subphenotypes could be explained by the presence of distinct risk haplotypes among different ethnic groups. In the same study, 2 more SNPs, rs4963128 and rs2246614 of the interferon-regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) gene, were tested for association with SLE. In contrast to what was observed in a European women cohort [20], no association with increased susceptibility for SLE in northern Han Chinese was reported. However, these 2 SNPs were associated with different subphenotypes of SLE. In particular, the rs4963128 was associated with the production of anti-SSA/B antibodies and lupus nephritis. The authors suggest that particular variants of the IRF7/KIAA1542 region may induce the generation of certain autoantibodies [32]. A recent small study of 190 Chinese patients with lupus nephritis reported a significant association of the rs2004640 polymorphism of the interferon-regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) gene with lupus nephritis but showed no association with any specific histological or clinical manifestation of lupus kidney disease [40]. However, a Swedish study, consisting of 272 SLE patients, investigating several SNPs related to IRF5 (including the rs2004640 polymorphism tested in the aforementioned Chinese study), as well as risk SNPs of STAT4 and TNF receptor-associated factor-1 complement component-5 (TRAF1-C5) demonstrated no association with lupus nephritis [41]. However, it should be noted that this was a study primarily investigating a possible overlap in genetic susceptibility between IgA nephropathy and lupus nephritis. Moreover, the small sample size of this study does not offer sufficiently powered results to contradict the positive association between risk alleles in STAT4 gene and lupus nephritis demonstrated in other studies. Taken together, the data provided by genetic studies further support the association of the type I IFN pathway with SLE susceptibility and possibly with lupus nephritis at least in some ethnic groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genetic studies investigating the association between several SNPs and both lupus nephritis and specific auto-antibodies in different ethnic populations.

| Author | No. of SLE patients | No. of healthy controls | Ethnic origin | Gene/SNP studied | Associations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nephritis | Autoantibodies | |||||

| Taylor et al. [38] | 1396 | 2560 | North Americans (European descent) |

STAT4/ rs7574865 |

P < 10−11* | Anti-dsDNA/ P < 10−19 |

| Kawasaki et al. [39] | 308 | 306 | Japanese |

STAT4/ rs7574865 |

P = 1.0 × 10−5** | Anti-dsDNA/ P = 4.9 × 10−5** |

| Qin et al. [40] | 190 | 182 | Chinese |

IRF5/ rs2004640T |

P = 0.002*** | NS |

| Vuong et al. [41] | 272 | 307 | Swedish |

-STAT4/ rs10181656 |

−NS | −NM |

|

-IRF5/ rs729302 rs4728142 rs2004640 rs3807306 rs10954213 rs11770589 rs2280714 |

−NS | −NM | ||||

|

- TRAF1-C5/ rs3761847 |

−NS | −NM | ||||

|

-TGFB1 / rs6957 rs2241715 rs1982073 rs1800469 |

−NS | −NM | ||||

| Li et al. [32] | 748 | 750 | Chinese (Northern Han) |

-STAT4 / rs7574865 |

−NS | −NS |

|

- IRF7/ KIAA1542 |

−P = 3.78 × 10−8 | -Anti-SSB/ P = 9.63x10 − 6 |

||||

| rs2246614† | −NS | −NS | ||||

| Luan et al. [42] | 675 | 678 | Chinese |

STAT4/ rs7582694 |

−NS | −NS |

| Sigurdsson et al. [24] | 695 | — | Swedish |

STAT4/ rs7582694 |

0.04 | Anti-dsDNA/ P = 5.3 × 10−7 |

*Severe nephritis (ESRD or severe progressing renal disease in renal biopsy), P < 10−4.**Statistical significance found only in the case-control arm of the study, whereas, in the case-only arm of the study, results both for nephritis and anti-dsDNA reached no statistical significance.

***While a statistically significant association with lupus nephritis was detected, no association was found with any specific clinical finding or histological type of nephritis.

†These 2 SNPs of the IRF7/KIAA1542 gene were not associated with SLE but only with specific SLE subphenotypes such as nephritis and anti-SSB.

NS: not statistically significant association. NM: not measured.

The rest of the abbreviations used are explained in the text.

This association between type I IFN and lupus nephritis in humans, which per se does not define a direct cause-effect relationship, has been put to test in many experimental murine lupus models in order to clarify the pathogenetic role of type I IFN in lupus renal disease. Studies in autoimmune prone mice that were treated with polyinosinic : polycytidylic acid (poly I : C), a synthetic double-stranded RNA ligand for TLR-3 that strongly induces type I IFN response, showed higher titers of anti-dsDNA antibodies, increased immune complex deposition, accumulation of activated lymphocytes and macrophages, and increased metalloproteinase activity that led to accelerated lupus nephritis and death [43–45]. Similar results supporting the pathogenetic effect of type I IFN in lupus glomerulonephritis were obtained from murine models injected with adenovirus expressing IFNα that leads to sustained release of that cytokine [45–49]. Moreover, recent studies in healthy (not lupus-prone) mice treated with 2,6,10,14-tetramethylpentadecane (pristane), an inducer of type I IFN through TLR-7 signaling, resulted in lupus-like nephritis, possibly through recruitment of inflammatory cells by type I IFN-inducible chemokines. Interestingly, different strains of mice under the effect of pristane develop histological lesions of diverse severity probably due to yet unknown genetic factors [50]. These data demonstrate that increased levels of type I IFN are able to induce lupus nephritis both in lupus-prone and healthy mice.

Additional evidence supporting the pivotal role of type I IFN in lupus glomerulonephritis derives from studies in New Zealand Black (NZB), New Zealand, mixed 2328 as well as pristane-treated mice deficient of the receptor of type I IFN (IFNAR−/−). The defective signaling through IFNAR in IFNAR−/− mice conferred protection from kidney disease and was associated with a decrease in the titers of lupus-specific autoantibodies and disease severity. In these models, a decrease in the proliferation and activation of dendritic cells as well as B and T cells was documented [51–53]. However, one study conducted in congenic MRL/lpr mice, a lupus-prone model that develops severe crescentic glomerulonephritis, reported that IFNAR deficiency caused a significant deterioration of renal disease. In contrast, deficiency of the type II IFN (IFNγ) receptor had beneficial effects on kidney disease, thus, suggesting a protective role for type I IFN pathway at least in this mouse model [54].

The role of TLRs and especially of TLR-7, responsive to ssRNA, and TLR-9, responsive to hypomethylated CpG-rich DNA, in type I IFN production in lupus is well established. Studies in mice that overexpress TLR-7 (Y-linked autoimmune accelerating locus mice—Yaa mice) or that were treated with pristane demonstrate the importance of type I IFN and TLR-7 signaling in accelerating and aggravating kidney injury [55–57]. Interestingly a study by Thibault et al. using the pristane-induced mouse model of SLE showed that upregulation of TLR-7 receptors in B cells and effective activation through TLR-7 and TLR-9 of B cells to produce lupus-specific autoantibodies require an intact type I IFN signaling pathway, thus, suggesting that type I IFN is upstream of TLR signaling in the activation of autoreactive B cells in SLE [58]. Moreover, activation of TLR-9 signaling pathway through CpG-rich DNA was shown to induce severe lupus nephritis in lupus-prone mice [59]. Additional confirmation was obtained from a study that tested a dual inhibitor of TLR-7 and TLR-9 (known to inhibit IFNα production by pDCs) in lupus-prone mice. A significant improvement of proteinuria, glomerulonephritis, and survival as well as a reduction of serum levels of nucleic acid-specific autoantibodies was observed [60].

Further evidence emphasizing the central role of type I IFN in lupus nephritis came from studies investigating the cellular source of type I IFN in lupus nephritis. pDCs are well known to be the main type I IFN-producing cells and potentially responsible for the systemic increase of type I IFN levels. Tucci et al. showed that peripheral pDCs were decreased in SLE patients and that this was associated with lupus nephritis. Moreover, this study demonstrated the presence of pDCs in the glomeruli of patients with severe lupus nephritis [61]. Interestingly, other studies suggest that immature monocytes recruited in the kidneys [62, 63] as well as resident renal cells [64] represent the main source of type I IFN in the kidney, thus, promoting end-organ disease in murine lupus nephritis models.

Finally a recent study by Ichii et al. showed that overexpression of the IFN-activated gene 202 (Ifi202) positively correlated with the progression of lupus nephritis in the B6.MRLc1 (82–100) mice. Ifi202 is an IFN-stimulated gene localized on the murine chromosome 1, and its overexpression in the kidneys and in the immune organs was confirmed in many lupus-prone mouse models such as BXSB, NZB/WF1 and MRL/lpr. This further supports the role of this IFN-stimulated gene in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis and lupus susceptibility in general [65].

Taken together, these data highlight the importance of the IFN system in lupus nephritis creating exciting new prospectives both at diagnostic and clinical levels. Interferon-induced chemokines, like macrophage chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) and others, seem to be highly sensitive biomarkers in the assessment of current disease activity and in the early detection of lupus nephritis flare [66, 67]. Moreover, inhibition of MCP-1 in a murine model of lupus nephritis showed significant amelioration of disease symptoms suggesting a new therapeutic approach to lupus kidney disease [68]. Zagury et al. successfully used an IFNα immunogen (termed IFNα kinoid) in mice with nephritis that transiently induces anti-IFNα antibodies resulting in net improvement of lupus nephritis [69]. On the other hand, MRL-Faslpr mice treated with IFNβ showed a significant amelioration of lupus nephritis in these mice suggesting that IFNβ exerts a local (rather than systemic) anti-inflammatory effect [70]. Additionally, phase I human clinical trials using anti-IFNα monoclonal antibody in patients with mild to moderate SLE showed promising results including suppression of type I IFN-inducible genes overexpression in whole blood and skin lesions, profound effects on signaling pathways such as BAFF, TNFα, IL-1β and consistent trends toward improvement in disease activity, reduced number of flares, and decreased requirement for new or increased immunosuppressive treatments. Preliminary data regarding the safety profile especially viral infections and major adverse events support further clinical development [71–73]. However, more data regarding the efficacy and safety of this treatment are awaited.

3. Type I IFN and Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (CLE)

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) is one of the most common autoimmune-associated skin diseases worldwide. In most cases, the disease is localized and limited to the skin area, without multisystemic involvement characteristic of SLE. While approximately 10%–40% of CLE—depending on the clinical subset of CLE—may transit to systemic disease, skin lesions in the setting of SLE can occur in up to 70% of patients during the disease course [74, 75]. While the pathogenesis of the CLE remains still unclear, a number of contributors—among them type I IFNs—have been proposed. In line with this hypothesis, lupus-like skin lesions have been previously reported at the site of injection of recombinant IFNα and IFNβ in patients with malignancy and multiple sclerosis respectively, while patients with generalized CLE features often experience flu-like symptoms [76, 77]. In patients with lupus, upregulation of the IFN-inducible antiviral protein Myxovirus A (MxA) in CLE has been first reported by Fah et al. [78], a finding which has been later confirmed in discoid (DLE), subacute cutaneous (SCLE), as well as other lupus-associated rashes [74, 79, 80]. Of interest, MxA expression was mainly seen in the epidermis and the upper dermis in DLE and SCLE, while, in rarer cases of lupus tumidus and lupus profundus, MxA was mainly detected in perivascular and subcutaneous areas, respectively, reflecting the distribution of the inflammatory infiltrate in different subsets of CLE [74].

Intracellular IFNα itself has been detected at mRNA and protein level in all lesional and more than half of not involved skin specimens from 11 lupus patients compared to only one out of 11 healthy controls [81]. The overexpression of IFN-related genes in nonpathological skin might be the result of genetically determined IFN pathway activation in these patients. Despite the enhanced expression of the IFNα-inducible IRF7 gene in CLE lesions reported by Meller et al. IFNα mRNA expression has been reported not significantly different in CLE skin compared to normal skin [82]. Subsequent studies detected the accumulation of pDCs—the classical IFNα producing cells—in lesional skin from patients with DLE, SLE, and lupus tumidus, providing an explanation for the previously reported reduced pDC numbers in lupus patients [79, 82–85]. Two pDC subsets have been identified according to their distribution pattern in CLE skin biopsies: a dermal pDCs subset (D-pDC) surrounding dermal vessels associated with Th1 responses and a second subset at the dermoepidermal junction zone (J-pDC) in association with cytotoxic T lymphocytes and subsequent local epithelial damage [84]. In the same study, a positive association was found between the pDC numbers and the density of the infiltrate, suggesting that IFNα production could regulate the degree of inflammation in the affected skin areas. Of note, a higher density infiltrate has been shown in DLE compared to SLE patients [84].

As a result of the locally produced IFNα, recruitment of lymphocytes in the CLE lesion occurs through the production of IFNα- and γ-inducible chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL1, which share a common lymphocytic CXCR3 receptor. Compared to IFNγ, IFNα has been shown to induce earlier production of these chemokines by keratinocytes, dermal endothelial cells, and dermal fibroblasts, ensuring a first wave of CXCR3+ lymphocytic migration—at the site of the CLE lesion [82]. These findings provide an explanation for the peripherally decreased number of CXCR3+—lymphocytes in these patients [86].

Serum type I IFN activity or expression of IFN-inducible genes in PMBCs from lupus patients was found to be associated with the presence of lupus-associated rashes in some but not all studies so far performed. Of interest, a positive trend between a history of photosensitivity and type I IFN-induced gene expression has been reported by Kirou et al. [9–13].

While the initial trigger for pDC activation in CLE remains elusive, observations of cutaneous lupus flares after sun exposure coupled with experimental evidence suggests UV irradiation as a central player in initiation of the lupus-associated skin injury. UV irradiation has been shown to exaggerate the already enhanced apoptosis of keratinocytes in CLE leading to generation of RNA and DNA fragments with subsequent secondary necrosis, production of a variety of IFNα-induced chemokines which in turn lead to lymphocytic recruitment and subsequent local inflammatory tissue injury [82, 87]. In accord with the proposed mechanism, inhibitors of TLR7 and TLR9 signaling in a lupus-prone murine model of interface dermatitis attenuated the skin lesions [88].

Moreover, a recently identified IFNα- and γ-induced protein—the GTPase human guanylate binding protein-1 (GBP-1)—is expressed by keratinocytes and endothelial cells in primary and ultraviolet- (UV-) induced skin lesions from patients with various subtypes of CLE compared to nonlesional skin [89]. It has also been recently demonstrated that the IFNα-inducible IFI16 protein—normally localized in the nucleus—translocates in the cytoplasm of affected skin cells from lupus patients and in UV irradiated keratinocytes—leading to generation of antibodies against the IFNα-inducible IFI16 recently detected in sera of lupus patients [90].

4. Type I IFN and Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (NPSLE)

Neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE)—among the most severe manifestations of SLE—includes a variety of manifestations involving central, peripheral, and autonomic nervous system as well as psychiatric disorders after other underlying causes have been carefully excluded. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric manifestations in the setting of SLE varies at a range approximately between 15% and 75%, depending of the ascertainment method used [91].

Several mechanisms have been so far implicated in the etiopathogenesis of NPSLE, including antibody-mediated vascular and parenchymal brain injury, concomitant atherosclerotic disease, or the effect of various inflammatory cytokines, including among others interleukin 1β (IL1β), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), IFNγ, and IFNα. These cytokines have been shown to induce peripheral depletion of tryptophan—previously implicated in the pathogenesis of depression—through stimulation of the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase [92]. IFNα has been also shown to induce the IFNγ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) and interleukin-6 (IL6) previously implicated in pathogenesis of CNS abnormalities [93].

Induction of SLE-like syndromes and neuropsychiatric manifestations have been reported after therapeutic use of IFNα approximately in one-third of patients mainly with hepatitis C or certain malignancies giving potential insights of type I IFN implication in lupus-related clinical syndromes [94–96]. While depression seems to be among the most common IFNα-related neuropsychiatric side effects and a main contraindication for IFNα administration, psychotic features, confusion, bipolar disorders, and seizures can also occur [92]. IFNα production by astrocytes in transgenic mouse models revealed structural and functional abnormalities ranging from seizures and severe behavioral disorders with high mortality to more subtle learning disabilities depending on high or low intrathecal levels of IFNα, respectively [97]. Notably, calcium and phosphorus deposition in the brain in this experimental model resembled the mineral deposition observed in basal ganglia from patients with the Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome, an early-onset encephalopathy with elevated CSF IFNα levels. The Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome is an autosomal recessive disease related to mutations in 5 genes, including among others the 3-repair DNA exonuclease 1 (TREX1), recently associated with lupus [98].

The first evidence of type I IFN implication in NPSLE pathogenesis comes from an early small study in the 1980s, in which elevated CSF levels of IFNα were detected in 2 out of 15 patients with SLE and CNS involvement but not in 20 non-NPSLE individuals. Both of these patients suffered from psychosis and were characterized by the presence of CSF oligoclonal IgG [99].

In accord with the above findings, elevated IFNα levels have been subsequently detected in CSFs of five out of 6 lupus patients with psychosis but with no other NP manifestations. In the brain autopsy of one of the study participants who died from generalized seizures, the presence of IFNα in neurons and microglia has been demonstrated by immunochemistry [100]. However, elevated IFNα levels—measured by immunoassay—were detected in approximately one-fifth of CSFs of both 28 NPSLE and 14 non-NPSLE patients, suggesting a limited diagnostic role for IFNα in clinical grounds [101]. While no significant differences have been observed in serum levels of interferogenic activity—measured by bioassay—between SLE patients with and without neuropsychiatric involvement, CSF interferogenic activity has been found to be elevated in NPSLE patients compared to controls with other autoimmune disorders and CNS features. Of note, remarkably lower levels of interferogenic activity have been observed in sera compared to CSFs of NPSLE patients. This was partially attributed to an inhibitory effect of serum IgG, providing a potential explanation for the success of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment in some cases of NPSLE [102] and other neurological diseases [103, 104]. In a recent study, involving 59 NPSLE patients, it was observed an association between acute flares of NP manifestations and elevated IFNα activity in the CSF [105].

The CSF interferogenic activity seems to result from pDC stimulation by CSF-containing immunocomplexes formed by autoantibodies and antigens released by neurocytotoxic Abs or other injured brain cells [93]. While pDCs have not been studied in the NPSLE patients brain cells, elevated number of pDC cells has been isolated from the CSF of other neuroinflammatory diseases [106].

In regard to peripherally detected type I IFN activity in NSPLE, in a cohort of 48 SLE patients reported by Feng et al., significantly higher IFN-inducible gene expression in peripheral mononuclear cells has been demonstrated in 9 patients, who ever suffered from psychosis or seizures, compared to those without those manifestations [13]. Such an association was not, however, observed in a larger cohort of 77 SLE patients by Kirou et al. (Table 1). Moreover, in a recent cross-sectional study including 58 SLE patients, no correlation between depression scores and type I IFN-induced gene expression in PBMC has been detected [107].

Taken together, these data imply a potential involvement of type I IFN system in pathogenesis of lupus-related CNS features. Prospective studies with larger number of patients and careful collection of clinical, serological, and imaging data are required to further understand its contribution in pathogenesis of NSPLE.

5. Type I IFN and Atherosclerosis in SLE Patients

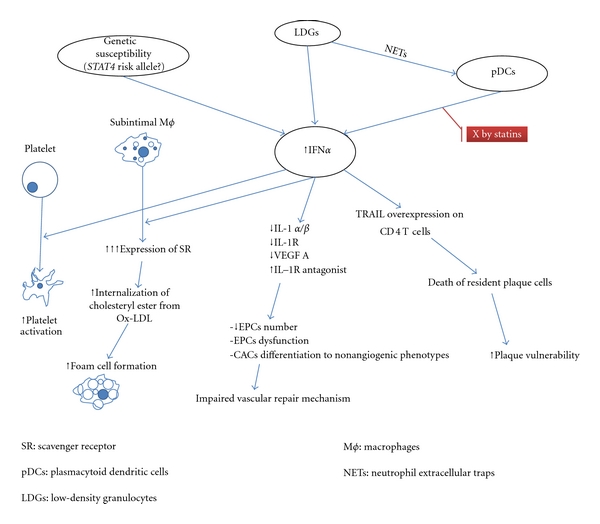

Extensive epidemiological studies in SLE patients demonstrate a bimodal distribution in mortality rates with the earlier peak attributed to infections and complications from kidney disease and/or neuropsychiatric lupus and a later peak mainly linked to atherosclerotic cardiovascular (CV) events [1]. A population-based case-control analysis, using general practice database data, found a relative CV disease risk of 2 for women with SLE [108, 109]. Strikingly, a fifty-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction was reported among premenopausal women with SLE [110]. While several traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis are more prevalent among SLE patients, they cannot fully explain their increased CV burden [111]. Additionally, the effect on CV risk of SLE is more pronounced comparing to the impact of other inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis [108]. These observations support the hypothesis that accelerated atherosclerosis and premature CV disease are significantly enhanced by factors inherent to the pathogenesis of SLE. Among these, increasing evidence designates type I IFN as a major player in promoting both the pathogenesis of SLE and atherosclerosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

It is widely believed that atherosclerosis results from chronic endothelial injury paired with a defective vascular repair mechanism leading to invasion of inflammatory cells, lipid deposition, vascular smooth muscle proliferation, and neointima formation. Several studies suggest that circulating myeloid-derived endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and myelomonocytic circulating angiogenic cells (CACs) are the key players in the vascular repair mechanism [112, 113].

Interestingly, reduced number and/or functional abnormalities of EPCs/CACs have been documented in patients with SLE [114–118]. Moreover, heightened type I IFN levels were associated with EPCs depletion and endothelial dysfunction in SLE patients possibly through IFNα-mediated apoptosis of EPCs/CACs and induction of differentiation of myeloid cells to nonangiogenic phenotypes. Neutralizing the type I IFN pathway redressed the abnormal EPC/CAC phenotype [119, 120]. In accord with the human studies, in a lupus-prone murine model, elevated levels of type I IFN led to reduced number and EPCs dysfunction [121]. Moreover, the presence of IFNα inhibited EPCs from nonlupus-prone mice to differentiate into mature endothelial cells. Thacker et al. showed that IFNα represses the transcription of the proangiogenic factors IL1 α and β and vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF) and upregulates the antiangiogenic IL1 receptor antagonist. In vivo confirmation of this antiangiogenic pathway of IFNα interfering with IL1 pathways was established by examining renal biopsies of patients with lupus nephritis [122].

Furthermore, studies investigating the cellular source of type I IFN add supporting evidence to the effects of type I IFN in vascular injury. pDCs have been implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and in particular in the destabilization of the atherosclerotic plaque which leads to acute vascular events through upregulation of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) on CD4+ T cells which enhance them to kill plaque-resident cells, thus, rendering the plaque vulnerable [123]. However, depletion of pDCs does not reverse the abnormal EPC/CAC phenotype in vitro. A recently studied subset of proinflammatory neutrophils, termed low-density granulocytes (LDG), was identified in the blood of SLE patients. LDGs exert cytotoxic effects on the endothelium and produce sufficient type I IFN to prevent EPCs from differentiating into mature endothelial cells. Depletion of LDGs restores the functional capacity of the EPCs/CACs in vitro, therefore, supporting a role of these abnormal cells and of type I IFN in the pathogenesis of vascular damage in SLE [124].

Interestingly a recent study investigating the immunomodulatory effects of statins in SLE demonstrated that simvastatin and pitavastatin significantly inhibit type I IFN production both from pDCs isolated from lupus patients and from healthy pDCs treated with sera from SLE patients. The inhibitory effect on type I IFN production was shown to be attributable to inactivation of Rho kinases (a family of downstream kinases of the TLR pathway) that results in inhibition of the p38 MAPK and Akt as well as prevention of IRF7 nuclear translocation. These findings imply that statins exert a beneficial effect in the atherosclerotic process not only due to its lipid-lowering properties but also through inhibition of the type I IFN production. It also provides a rationale for a potential therapeutic use of statins in IFN-mediated autoimmune diseases such as SLE [125].

An additional pathway by which type I IFN may be implicated in CV disease is through platelet activation. In a recent study, Lood et al. demonstrated that, in patients with lupus, platelets are activated and overexpress type I IFN-regulated proteins comparing to platelets from healthy controls. Given that the same platelet phenotype has been observed in patients with a history of vascular disease, they hypothesized that type I IFN-induced platelet activation could be implicated in the development of vascular disease in SLE [126].

Further supporting evidence for the role of type I IFN in atherosclerosis and especially in the formation of foam cells came from a study by Li et al. [127]. Foam cells derive from infiltrating monocytes in the subintima where they differentiate into macrophages. Upon exposure to oxidized-LDL (ox-LDL), macrophages expressing scavenger receptors (SR) internalize cholesteryl ester from ox-LDL and are transformed into foam cells which represent the primary components of the early atherosclerotic lesion. In this study, IFNα priming induced upregulation of SR in the macrophages and increased foam-cell formation. Furthermore, peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with SLE overexpressed SR which was positively correlated with increased type I IFN activity.

Finally, a recent Swedish study showed that SLE patients with the risk allele rs10181656(G) in the STAT4 gene had a significantly increased risk of ischemic cerebrovascular disease (ICVD), comparable in magnitude to that of hypertension. Moreover, this SNP was associated with the presence of two or more antiphospholid antibodies (aPLs). This study indicates that a genetic predisposition involving the type I IFN pathway is an important and previously unrecognised risk factor for ICVD in SLE and that aPLs may be one underlying mechanism [128].

These data indicate that premature atherosclerosis in SLE patients can at least partially be attributed to increased activation of the type I IFN system. Current attempts to block the type I IFN activity in SLE patients may provide therapeutic approaches that achieve successful overall disease activity control and reduce the fatal vascular events that afflict these patients.

6. Concluding Remarks

Over the past years, the role of type I interferon system in generation of distinct lupus-related clinical phenotypes arising from skin, renal, and CNS involvement has been increasingly appreciated. Moreover, growing evidence suggests the implication of type I IFN pathway in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, a frequent comorbidity in these patients, often not fully explained by the presence of co-existing traditional CV risk factors. Careful characterization of clinical features associated with heightened IFN levels would further increase our insight into lupus pathogenesis allowing the potential use of type I interferon as a therapeutic target for lupus patients characterized by specific clinical and/or serological phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Profs M. K. Crow, MD, and H. M. Moutsopoulos, MD, for their inspiration, guidance and fruitful suggestions. They are also grateful to Dr. D. Ioakeimidis, MD, for providing valuable clinical data and continuous support.

References

- 1.Borchers AT, Naguwa SM, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME. The geoepidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2010;9(5):A277–A287. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooks JJ, Moutsopoulos HM, Geis SA. Immune interferon in the circulation of patients with autoimmune disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1979;301(1):5–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197907053010102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronnblom LE, Alm GV, Oberg KE. Possible induction of systemic lupus erythematosus by interferon α-treatment in a patient with a malignant carcinoid tumour. Journal of Internal Medicine. 1990;227(3):207–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett L, Palucka AK, Arce E, et al. Interferon and granulopoiesis signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus blood. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;197(6):711–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ronnblom L, Alm GV, Eloranta ML. The type I interferon system in the development of lupus. Seminars in Immunology. 2011;23(2):113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lande R, Ganguly D, Facchinetti V, et al. Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self-DNA-peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3(73):p. 73ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Romo GS, Caielli S, Vega B, et al. Netting neutrophils are major inducers of type I IFN production in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3(73):p. 73ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanayama Y, Kim T, Inariba H, et al. Possible involvement of interferon α in the pathogenesis of fever in systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1989;48(10):861–863. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.10.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bengtsson AA, Sturfelt G, Truedsson L, et al. Activation of type I interferon system in systemic lupus erythematosus correlates with disease activity but not with antiretroviral antibodies. Lupus. 2000;9(9):664–671. doi: 10.1191/096120300674499064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(5):2610–2615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dall’era MC, Cardarelli PM, Preston BT, Witte A, Davis JC. Type I interferon correlates with serological and clinical manifestations of SLE. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2005;64(12):1692–1697. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirou KA, Lee C, George S, Louca K, Peterson MGE, Crow MK. Activation of the interferon- α pathway identifies a subgroup of systemic lupus erythematosus patients with distinct serologic features and active disease. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;52(5):1491–1503. doi: 10.1002/art.21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng X, Wu H, Grossman JM, et al. Association of increased interferon-inducible gene expression with disease activity and lupus nephritis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(9):2951–2962. doi: 10.1002/art.22044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weckerle CE, et al. Network analysis of associations between serum interferon-α activity, autoantibodies, and clinical features in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2011;63(4):1044–1053. doi: 10.1002/art.30187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bagavant H, Fu SM. Pathogenesis of kidney disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2009;21(5):489–494. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832efff1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rich SA. Human lupus inclusions and interferon. Science. 1981;213(4509):772–775. doi: 10.1126/science.6166984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson KS, Huang JF, Zhu J, et al. Characterization of heterogeneity in the molecular pathogenesis of lupus nephritis from transcriptional profiles of laser-captured glomeruli. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113(12):1722–1733. doi: 10.1172/JCI19139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papadimitraki ED, Tzardi M, Bertsias G, Sotsiou E, Boumpas DT. Glomerular expression of Toll-like receptor-9 in lupus nephritis but not in normal kidneys: implications for the amplification of the inflammatory response. Lupus. 2009;18(9):831–835. doi: 10.1177/0961203309103054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moser KL, Kelly JA, Lessard CJ, Harley JB. Recent insights into the genetic basis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes and Immunity. 2009;10(5):373–379. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harley JB, Alarcón-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(2):204–210. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harley IT, Kaufman KM, Langefeld CD, Harley JB, Kelly JA. Genetic susceptibility to SLE: new insights from fine mapping and genome-wide association studies. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10(5):285–290. doi: 10.1038/nrg2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kariuki SN, Moore JG, Kirou KA, Crow MK, Utset TO, Niewold TB. Age- and gender-specific modulation of serum osteopontin and interferon- α by osteopontin genotype in systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes and Immunity. 2009;10(5):487–494. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kariuki SN, Crow MK, Niewold TB. The PTPN22 C1858T polymorphism is associated with skewing of cytokine profiles toward high interferon- α activity and low tumor necrosis factor α levels in patients with lupus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58(9):2818–2823. doi: 10.1002/art.23728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sigurdsson S, Nordmark G, Garnier S, et al. A risk haplotype of STAT4 for systemic lupus erythematosus is over-expressed, correlates with anti-dsDNA and shows additive effects with two risk alleles of IRF5. Human Molecular Genetics. 2008;17(18):2868–2876. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, et al. STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(10):977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kariuki SN, Kirou KA, MacDermott EJ, Barillas-Arias L, Crow MK, Niewold TB. Cutting edge: autoimmune disease risk variant of STAT4 confers increased sensitivity to IFN-α in lupus patients in vivo. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182(1):34–38. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham RR, Kyogoku C, Sigurdsson S, et al. Three functional variants of IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) define risk and protective haplotypes for human lupus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(16):6758–6763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701266104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee-Kirsch MA, Gong M, Chowdhury D, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the 3’–5’ DNA exonuclease TREX1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Genetics. 2007;39(9):1065–1067. doi: 10.1038/ng2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abelson AK, Delgado-Vega AM, Kozyrev SV, et al. STAT4 associates with systemic lupus erythematosus through two independent effects that correlate with gene expression and act additively with IRF5 to increase risk. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2009;68(11):1746–1753. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.097642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob CO, Zhu J, Armstrong DL, et al. Identification of IRAK1 as a risk gene with critical role in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(15):6256–6261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901181106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salloum R, Franek BS, Kariuki SN, et al. Genetic variation at the IRF7/PHRF1 locus is associated with autoantibody profile and serum interferon-α activity in lupus patients. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2010;62(2):553–561. doi: 10.1002/art.27182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li P, Cao C, Luan H, et al. Association of genetic variations in the STAT4 and IRF7/KIAA1542 regions with systemic lupus erythematosus in a Northern Han Chinese population. Human Immunology. 2011;72(3):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos PS, Williams AH, Ziegler JT, et al. Genetic analyses of interferon pathway-related genes reveals multiple new loci associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2011;63(7):2049–2057. doi: 10.1002/art.30356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawasaki A, Furukawa H, Kondo Y, et al. TLR7 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the 3’ untranslated region and intron 2 independently contribute to systemic lupus erythematosus in Japanese women: a case-control association study. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2011;13(2):p. R41. doi: 10.1186/ar3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu Q, Zhao J, Qian X, et al. Association of a functional IRF7 variant with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2011;63(3):749–754. doi: 10.1002/art.30193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Namjou B, Kothari PH, Kelly JA, et al. Evaluation of the TREX1 gene in a large multi-ancestral lupus cohort. Genes and Immunity. 2011;12(4):270–279. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sigurdsson S, Nordmark G, Goring HH, et al. Polymorphisms in the tyrosine kinase 2 and interferon regulatory factor 5 genes are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;76(3):528–537. doi: 10.1086/428480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor KE, Remmers EF, Lee AT, et al. Specificity of the STAT4 genetic association for severe disease manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. PloS Genetics. 2008;4(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000084. Article ID e1000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawasaki A, Ito I, Hikami K, et al. Role of STAT4 polymorphisms in systemic lupus erythematosus in a Japanese population: a case-control association study of the STAT1-STAT4 region. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2008;10(5):p. R113. doi: 10.1186/ar2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qin L, Lv J, Zhou X, Hou P, Yang H, Zhang H. Association of IRF5 gene polymorphisms and lupus nephritis in a Chinese population. Nephrology. 2010;15(7):710–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vuong MT, Gunnarsson I, Lundberg S, et al. Genetic risk factors in lupus nephritis and IgA nephropathy—no support of an overlap. Plos one. 2010;5(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010559. Article ID e10559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luan H, Li P, Cao C, et al. A single-nucleotide polymorphism of the STAT4 gene is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in female Chinese population. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1767-9. Rheumatology International. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braun D, Geraldes P, Demengeot J. Type I Interferon controls the onset and severity of autoimmune manifestations in lpr mice. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2003;20(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(02)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jorgensen TN, Thurman J, Izui S, et al. Genetic susceptibility to polyI:C-induced IFN α/β-dependent accelerated disease in lupus-prone mice. Genes and Immunity. 2006;7(7):555–567. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Triantafyllopoulou A, Franzke CW, Seshan SV, et al. Proliferative lesions and metalloproteinase activity in murine lupus nephritis mediated by type I interferons and macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(7):3012–3017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914902107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mathian A, Weinberg A, Gallegos M, Banchereau J, Koutouzov S. IFN-α induces early lethal lupus in preautoimmune (New Zealand Black × New Zealand White)F1 but not in BALB/c mice. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(5):2499–2506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fairhurst AM, Mathian A, Connolly JE, et al. Systemic IFN-α drives kidney nephritis in B6.Sle123 mice. European Journal of Immunology. 2008;38(7):1948–1960. doi: 10.1002/eji.200837925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramanujam M, Kahn P, Huang W, et al. Interferon-α treatment of female (NZW × BXSB)F1 mice mimics some but not all features associated with the Yaa mutation. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60(4):1096–1101. doi: 10.1002/art.24414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Z, Bethunaickan R, Huang W, et al. Interferon-α accelerates murine systemic lupus erythematosus in a T cell-dependent manner. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2011;63(1):219–229. doi: 10.1002/art.30087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reeves WH, Lee PY, Weinstein JS, Satoh M, Lu L. Induction of autoimmunity by pristane and other naturally occurring hydrocarbons. Trends in Immunology. 2009;30(9):455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santiago-Raber ML, Baccala R, Haraldsson KM, et al. Type-I interferon receptor deficiency reduces lupus-like disease in NZB mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;197(6):777–788. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agrawal H, Jacob N, Carreras E, et al. Deficiency of type I IFN receptor in lupus-prone New Zealand mixed 2328 mice decreases dendritic cell numbers and activation and protects from disease. Journal of Immunology. 2009;183(9):6021–6029. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nacionales DC, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Lee PY, et al. Deficiency of the type I interferon receptor protects mice from experimental lupus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2007;56(11):3770–3783. doi: 10.1002/art.23023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hron JD, Peng SL. Type I IFN protects against murine lupus. Journal of Immunology. 2004;173(3):2134–2142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee PY, Kumagai Y, Li Y, et al. TLR7-dependent and FcγR-independent production of type I interferon in experimental mouse lupus. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205(13):2995–3006. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fairhurst AM, Hwang SH, Wang A, et al. Yaa autoimmune phenotypes are conferred by overexpression of TLR7. European Journal of Immunology. 2008;38(7):1971–1978. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Savarese E, Steinberg C, Pawar RD, et al. Requirement of Toll-like receptor 7 for pristane-induced production of autoantibodies and development of murine lupus nephritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58(4):1107–1115. doi: 10.1002/art.23407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thibault DL, Chu AD, Graham KL, et al. IRF9 and STAT1 are required for IgG autoantibody production and B cell expression of TLR7 in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(4):1417–1426. doi: 10.1172/JCI30065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pawar RD, Patole PS, Ellwart A, et al. Ligands to nucleic acid-specific Toll-like receptors and the onset of lupus nephritis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;17(12):3365–3373. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barrat FJ, Meeker T, Chan JH, Guiducci C, Coffmann RL. Treatment of lupus-prone mice with a dual inhibitor of TLR7 and TLR9 leads to reduction of autoantibody production and amelioration of disease symptoms. European Journal of Immunology. 2007;37(12):3582–3586. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tucci M, Quatraro C, Lombardi L, Pellegrino C, Dammacco F, Silvestris F. Glomerular accumulation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in active lupus nephritis: role of interleukin-18. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58(1):251–262. doi: 10.1002/art.23186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee PY, Weinstein JS, Nacionales DC, et al. A novel type i IFN-producing cell subset in murine lupus. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180(7):5101–5108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee PY, Li Y, Kumagai Y, et al. Type I interferon modulates monocyte recruitment and maturation in chronic inflammation. American Journal of Pathology. 2009;175(5):2023–2033. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fairhurst AM, Xie C, Fu Y, et al. Type I interferons produced by resident renal cells may promote end-organ disease in autoantibody-mediated glomerulonephritis. Journal of Immunology. 2009;183(10):6831–6838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ichii O, Kamikawa A, Otsuka S, et al. Overexpression of interferon-activated gene 202 (Ifi202) correlates with the progression of autoimmune glomerulonephritis associated with the MRL chromosome 1. Lupus. 2010;19(8):897–905. doi: 10.1177/0961203310362534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bauer JW, Petri M, Batliwalla FM, et al. Interferon-regulated chemokines as biomarkers of systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity: a validation study. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60(10):3098–3107. doi: 10.1002/art.24803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fu Q, Chen X, Cui H, et al. Association of elevated transcript levels of interferon-inducible chemokines with disease activity and organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2008;10(5) doi: 10.1186/ar2510. Article ID R112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kulkarni O, Pawar RD, Purschke W, et al. Spiegelmer inhibition of CCL2/MCP-1 ameliorates lupus nephritis in MRL-(Fas)lpr mice. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2007;18(8):2350–2358. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zagury D, Buanec HL, Mathian A, et al. IFN α kinoid vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies prevent clinical manifestations in a lupus flare murine model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(13):5294–5299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900615106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schwarting A, Paul K, Tschirner S, et al. Interferon-β: a therapeutic for autoimmune lupus in MRL-Fas lpr mice. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2005;16(11):3264–3272. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004111014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yao Y, Richman L, Higgs BW, et al. Neutralization of interferon-α/β-inducible genes and downstream effect in a phase I trial of an anti-interferon-α monoclonal antibody in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60(6):1785–1796. doi: 10.1002/art.24557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yao Y, Higgs BW, Richman L, White B, Jallal B. Use of type I interferon-inducible mRNAs as pharmacodynamic markers and potential diagnostic markers in trials with sifalimumab, an anti-IFN α antibody, in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2010;12(supplement 1):p. S6. doi: 10.1186/ar2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Merrill JT, Wallace DJ, Petri M. Safety profile and clinical activity of sifalimumab, a fully human anti-interferon {α} monoclonal antibody, in systemic lupus erythematosus: a phase I, multicentre, double-blind randomised study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2011;70(11):1905–1913. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wenzel J, Zahn S, Bieber T, Tuting T. Type I interferon-associated cytotoxic inflammation in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Archives of Dermatological Research. 2009;301(1):83–86. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0892-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Klein RS, Morganroth PA, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus and the cutaneous lupus erythematosus disease area and severity index instrument. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 2010;36(1):33–51. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Arrue I, Saiz A, Ortiz-Romero PL, Rodriguez-Peralto JL. Lupus-like reaction to interferon at the injection site: report of five cases. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. 2007;34(supplement 1):18–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wenzel J, Bieber T, Uerlich M, Tuting T. Systemic treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Journal of the German Society of Dermatology. 2003;1(9):694–704. doi: 10.1046/j.1610-0387.2003.03024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fah J, Pavlovic J, Burg G. Expression of MxA protein in inflammatory dermatoses. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 1995;43(1):47–52. doi: 10.1177/43.1.7822763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Farkas L, Beiske K, Lund-Johansen F, Brandtzaeg P, Jahnsen FL. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (natural interferon-α/β-producing cells) accumulate in cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions. American Journal of Pathology. 2001;159(1):237–243. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61689-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wenzel J, Uerlich M, Worrenkamper E, Freutel S, Bieber T, Tuting T. Scarring skin lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus are characterized by high numbers of skin-homing cytotoxic lymphocytes associated with strong expression of the type I interferon-induced protein MxA. British Journal of Dermatology. 2005;153(5):1011–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blomberg S, Eloranta ML, Cederblad B, Nordlind K, Alm GV, Ronnblom L. Presence of cutaneous interferon-α producing cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2001;10(7):484–490. doi: 10.1191/096120301678416042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meller S, Winterberg F, Gilliet M, et al. Ultraviolet radiation-induced injury, chemokines, and leukocyte recruitment: an amplification cycle triggering cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;52(5):1504–1516. doi: 10.1002/art.21034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cederblad B, Blomberg S, Vallin H, Perers A, Alm GV, Ronnblom L. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus have reduced numbers of circulating natural interferon-α-producing cells. Journal of Autoimmunity. 1998;11(5):465–470. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1998.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vermi W, Lonardi S, Morassi M, et al. Cutaneous distribution of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in lupus erythematosus. Selective tropism at the site of epithelial apoptotic damage. Immunobiology. 2009;214(9-10):877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Obermoser G, Schwingshackl P, Weber F, et al. Recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in ultraviolet irradiation-induced lupus erythematosus tumidus. British Journal of Dermatology. 2009;160(1):197–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wenzel J, Worenkamper E, Freutel S, et al. Enhanced type I interferon signalling promotes Th1-biased inflammation in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Journal of Pathology. 2005;205(4):435–442. doi: 10.1002/path.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuhn A, Herrmann M, Kleber S, et al. Accumulation of apoptotic cells in the epidermis of patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus after ultraviolet irradiation. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(3):939–950. doi: 10.1002/art.21658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guiducci C, Tripodo C, Gong M, et al. Autoimmune skin inflammation is dependent on plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation by nucleic acids via TLR7 and TLR9. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207(13):2931–2942. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Naschberger E, Wenzel J, Kretz CC, Herrmann M, Sturzl M, Kuhn A. Increased expression of guanylate binding protein-1 in lesional skin of patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Experimental Dermatology. 2011;20(2):102–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Costa S, Borgogna C, Mondini M, et al. Redistribution of the nuclear protein IFI16 into the cytoplasm of ultraviolet B-exposed keratinocytes as a mechanism of autoantigen processing. British Journal of Dermatology. 2011;164(2):282–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brey RL, Holliday SL, Saklad AR, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes in lupus: prevalence using standardized definitions. Neurology. 2002;58(8):1214–1220. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.8.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wichers M, Maes M. The psychoneuroimmuno-pathophysiology of cytokine-induced depression in humans. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;5(4):375–388. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702003103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Santer DM, Yoshio T, Minota S, Moller T, Elkon KB. Potent induction of IFN-α and chemokines by autoantibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neuropsychiatric lupus. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182(2):1192–1201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dieperink E, Willenbring M, Ho SB. Neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with hepatitis C and interferon α: a review. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):867–876. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ronnblom LE, Alm GV, Oberg KE. Autoimmunity after α-interferon therapy for malignant carcinoid tumors. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1991;115(3):178–183. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-3-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ehrenstein MR, McSweeney E, Swana M, Worman CP, Goldstone AH, Isenberg DA. Appearance of anti-DNA antibodies in patients treated with interferon-α. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1993;36(2):279–280. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Campbell IL, Krucker T, Steffensen S, et al. Structural and functional neuropathology in transgenic mice with CNS expression of IFN-α. Brain Research. 1999;835(1):46–61. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ramantani G, Niggemann P, Bast T, Lee-Kirsch MA. Reconciling neuroimaging and clinical findings in Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome: an autoimmune-mediated encephalopathy. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2010;31(7):E62–E63. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Winfield JB, Shaw M, Silverman LM. Intrathecal IgG synthesis and blood-brain barrier impairment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and central nervous system dysfunction. American Journal of Medicine. 1983;74(5):837–844. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shiozawa S, Kuroki Y, Kim M, Hirohata S, Ogino T. Interferon-α in lupus psychosis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1992;35(4):417–422. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jonsen A, Bengtsson AA, Nived O, et al. The heterogeneity of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus is reflected in lack of association with cerebrospinal fluid cytokine profiles. Lupus. 2003;12(11):846–850. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu472sr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Levy Y, Sherer Y, Ahmed A, et al. A study of 20 SLE patients with intravenous immunoglobulin—clinical and serologic response. Lupus. 1999;8(9):705–712. doi: 10.1191/096120399678841007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dalakas MC. Role of IVIg in autoimmune, neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders of the central nervous system: present and future prospects. Journal of Neurology. 2006;253(5):V25–V32. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-5004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Linker RA, Gold R. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin and plasma exchange in neurological disease. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2008;21(3):358–365. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282ff5b8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Svenungusson E, Mavragani CP, Hopia L, et al. Acute flares of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE) are sometimes associated with spikes of interferon-alpha activity in the CSF. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2010;62:p. 1181. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pashenkov M, Huang YM, Kostulas V, Haglund M, Soderstrom M, Link H. Two subsets of dendritic cells are present in human cerebrospinal fluid. Brain. 2001;124, part 3:480–492. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kellner ES, Lee PY, Li Y, et al. Endogenous type-I interferon activity is not associated with depression or fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2010;223(1-2):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fischer LM, Schlienger RG, Matter C, Jick H, Meier CR. Effect of rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus on the risk of first-Time acute myocardial infarction. American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;93(2):198–200. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hak AE, Karlson EW, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Costenbader KH. Systemic lupus erythematosus and the risk of cardiovascular disease: results from the nurses’ health study. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2009;61(10):1396–1402. doi: 10.1002/art.24537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, et al. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;145(5):408–415. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, Grodzicky T, et al. Traditional Framingham risk factors fail to fully account for accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2001;44(10):2331–2337. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200110)44:10<2331::aid-art395>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zampetaki A, Kirton JP, Xu Q. Vascular repair by endothelial progenitor cells. Cardiovascular Research. 2008;78(3):413–421. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Briasoulis A, Tousoulis D, Antoniades C, Papageorgiou N, Stefanadis C. The role of endothelial progenitor cells in vascular repair after arterial injury and atherosclerotic plaque development. Cardiovascular Therapeutics. 2011;29(2):125–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2009.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Baker JF, Zhang L, Imadojemu S, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells are reduced in SLE in the absence of coronary artery calcification. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1730-9. Rheumatology International. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Deng XL, Li XX, Liu XY, Sun L, Liu R. Comparative study on circulating endothelial progenitor cells in systemic lupus erythematosus patients at active stage. Rheumatology International. 2010;30(11):1429–1436. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Grisar J, Steiner CW, Bonelli M, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus patients exhibit functional deficiencies of endothelial progenitor cells. Rheumatology. 2008;47(10):1476–1483. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Westerweel PE, Luijten RK, Hoefer IE, Koomans HA, Derksen RH, Verhaar MC. Haematopoietic and endothelial progenitor cells are deficient in quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2007;66(7):865–870. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Moonen JR, de Leeuw K, van Seijen XJ, et al. Reduced number and impaired function of circulating progenitor cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2007;9(4):p. R84. doi: 10.1186/ar2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lee PY, Li Y, Richards HB, et al. Type I interferon as a novel risk factor for endothelial progenitor cell depletion and endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2007;56(11):3759–3769. doi: 10.1002/art.23035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Denny MF, Thacker S, Mehta H, et al. Interferon-α promotes abnormal vasculogenesis in lupus: a potential pathway for premature atherosclerosis. Blood. 2007;110(8):2907–2915. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Thacker SG, Duquaine D, Park J, Kaplan MJ. Lupus-prone New Zealand Black/New Zealand white F1 mice display endothelial dysfunction and abnormal phenotype and function of endothelial progenitor cells. Lupus. 2010;19(3):288–299. doi: 10.1177/0961203309353773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Thacker SG, Berthier CC, Mattinzoli D, Rastaldi MP, Kretzler M, Kaplan MJ. The detrimental effects of IFN-α on vasculogenesis in lupus are mediated by repression of IL-1 pathways: potential role in atherogenesis and renal vascular rarefaction. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(7):4457–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Niessner A, Weyand CM. Dendritic cells in atherosclerotic disease. Clinical Immunology. 2010;134(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Denny MF, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, et al. A distinct subset of proinflammatory neutrophils isolated from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus induces vascular damage and synthesizes type I IFNs. Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(6):3284–3297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Amuro H, Ito T, Miyamoto R, et al. Statins, inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, function as inhibitors of cellular and molecular components involved in type I interferon production. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2010;62(7):2073–2085. doi: 10.1002/art.27478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lood C, Amisten S, Gullstrand B, et al. Platelet transcriptional profile and protein expression in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: up-regulation of the type I interferon system is strongly associated with vascular disease. Blood. 2010;116(11):1951–1957. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Li J, Fu Q, Cui H, et al. Interferon-α priming promotes lipid uptake and macrophage-derived foam cell formation: a novel link between interferon-α and atherosclerosis in lupus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2011;63(2):492–502. doi: 10.1002/art.30165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Svenungsson E, Gustafsson J, Leonard D, et al. A STAT4 risk allele is associated with ischaemic cerebrovascular events and anti-phospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2010;69(5):834–840. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.115535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]