There are major changes in health care that will impact all areas of medicine, including sleep medicine. Given the growing cost of health care and the current fiscal state of the United States, there is no doubt that more changes are coming. Added to these general changes, there are specific issues facing sleep medicine. The major financial base of sleep medicine is reimbursement for in-laboratory polysomnography. The recent change in moving to home-based sleep studies is a disruptive innovation.

Many aspects of our economy are facing change due to new technology and other factors. This includes bookstores, companies renting home movies, newspapers, etc. The challenge is to recognize the need for change and implement change strategies before it is too late. That sleep medicine has recognized the need for change is indisputable as the excellent commentary by Dr. Patrick Strollo, then President of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, wrote last year in this journal.1 What is unclear is whether, as a field, we have a strategy to address change. Change is hard and the natural tendency is to try to maintain the status quo. However, given the forces currently at play, maintaining the status quo is a high risk strategy, and if pursued for too long could have a devastating outcome on our field and the patients we serve.

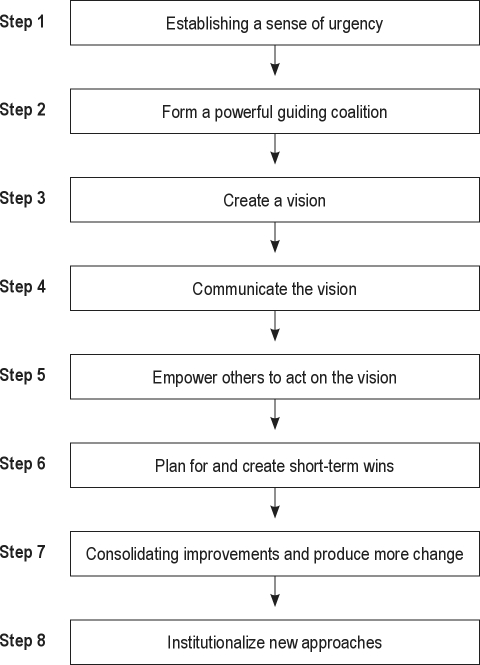

There are common aspects of strategies for change in any endeavor. These have been described by John Kotter in the Harvard Business Review.2 They are outlined in Figure 1. Currently it is unclear whether nationally in sleep medicine we are on this ladder, and hence there is much work ahead of us.

Figure 1.

Steps in transformation

An early step in a transformation strategy is creating a sense of urgency. This is essential to unite all constituencies behind the need for change. Some constituencies will simply hope that the current situation continues and hence will hold out to the end (if not beyond). Anybody following recent events in Massachusetts will appreciate the sense of urgency for sleep medicine and the need to take a proactive leadership role in working with payors to design and implement a strategy for responsible change. In brief, a relatively small, central Massachusetts-based insurance company, Fallon Community Health Plan (FCHP), initially made the change in 2010 and was swiftly followed by Tufts Health Plan (THP) in January of 2011. Each signed a contract with Sleep Management Solutions (SMS) and CareCore National (a national benefits management company) to manage sleep studies and associated DME needs of their non-Medicare/Medicaid HMO and PPO subscribers. CareCore National acts as gatekeeper, through a prior authorization process, and directs patients requiring sleep studies to specific modalities (HST vs. in-lab) based on CareCore National criteria. SMS is the exclusive provider of HST and the corresponding PAP therapy for the Fallon Plan. SMS is the exclusive provider of HST for the Tufts plan, and existing, qualified network providers may provide PAP therapy regardless of whether the study was requested by a sleep physician at a sleep center.

The stated goals from insurers are to ensure the appropriate sleep diagnostic setting and manage the delivery of therapy services while improving outcomes. The majority of patients are being directed to HST rather than in-laboratory polysomnography. It should be noted that there has been very limited success in challenging diagnostic testing determinations by CareCore National. It is still unclear what percentage of those directed to HST actually receive studies and treatment.

Recently, August 1, 2011, Massachusetts-based Harvard Pilgrim HealthCare (HPHC) instituted a similar program through CareCore National. The triage of sleep study requests to HST or in-lab polysomnography is identical to the other carriers. However, HPHC is using select qualified providers from their existing network to deliver HST, in-lab polysomnography, and PAP therapy to their subscribers versus any exclusive provider relationship with Sleep Management Solutions.

This transformation came rapidly in Massachusetts over a period of 18 months. Sleep centers were initially caught off guard. It has resulted in a number of sleep centers in Massachusetts closing. Currently Sleep HealthCenters, that services some of the Harvard hospitals, has seen 10% to 20% of its activity overall switched from in-laboratory to in-home sleep studies, though the percentages are up to 60% for the previously specified healthcare plans. They anticipate that once the largest plan—Blue Cross—goes in this direction as well, that 50% to 60% of their sleep study activity will be home studies (personal communication—Dr. L. Epstein, Chief Medical Officer, Sleep HealthCenters).

While one could argue that this is simply a Massachusetts phenomenon given that state's need to control health care costs following the health care plan introduced by then Governor Romney, this is not a powerful argument. We have already seen United Health Care indicating that they will move in this direction, and by November they will have a company in place managing their sleep studies nationally with a major shift to home studies. Thus, while the speed of this transformation may vary across the country, it is safe to argue that this change will take place in almost all, if not all, areas.

The argument of course is that these companies mandating how studies are done with a focus on home studies may control costs of diagnosis but they will not deliver good outcomes of care. This is a valid argument, but unfortunately we are, as a field, in a weak position to mount this argument, since we do not track the outcomes of our accredited centers. As indicated in the 2006 Institute of Medicine Report, “Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem,”3 sleep medicine is a chronic disease management knowledge-based discipline, not a diagnostic discipline. The report recommended that accreditation standards should focus primarily on outcomes of care. It is unfortunate that much of our focus has been on the diagnostic aspects of the polysomnogram, not on quality outcomes. That sleep medicine should focus on outcomes of care rather than the diagnosis was also proposed in 20064 by one of the pioneers of our field—Dr. Peretz Lavie—who is now President of the Technicon University in Israel.

This argument leads to a clear vision (a subsequent necessary step in the transformation process), i.e., that sleep medicine should be a field with a focus on quality outcomes of care. This should not just be for sleep apnea, but for all sleep disorders. We need to avoid patient experiences such as those documented in the book by Patricia Morrisroe5 of a patient with insomnia.

The notion of focusing on quality outcomes is very much in line with the vision of an integrated sleep center that the American Academy of Sleep Medicine is discussing with Medicare as a demonstration project. While this is a move in the right direction, it is concerning whether the current speed of change will result in this effort being too little too late.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has the ability to move our field to a new, patient-centered and outcomes-based delivery model. This would require an adjustment of the current accreditation standards. It would mean establishing metrics that consist of quantifiable standards and work with centers to achieve these metrics as part of the accreditation process and site visit. It is of course unrealistic that this will occur overnight. However, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine could indicate that change is coming and give a period of 12-18 months to allow centers to tool up to accommodate this new direction. Some centers may choose to give up their accreditation, thereby electing to be a casualty of positive change. The group that will transform will be focused on quality outcomes and place our field in the very best position to deal with the major market and political forces that are now in play.

At the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) Sleep Center, we are aggressively pursuing development of an outcomes-based approach to chronic care. The fundamental principles of this approach are: a) focus on outcomes of care and b) provide for diagnosis and treatment for all sleep disorders. The latter needs to include a well-functioning behavioral sleep medicine program.

Building this model requires a focus on the following aspects of care. First, one needs to build capability not only for in-laboratory sleep studies but also for in-home studies. Outcomes need to be defined and the relevant tools put in place to capture data. For sleep apnea a starting set of outcomes would be the following: sleep apnea symptoms, Epworth Sleepiness Score, Functional Outcomes of Sleepiness Questionnaire, PAP compliance, blood pressure, HbA1C (for diabetics), and medication use. The concept of an integrated center envisages that the center would provide alternative therapies for sleep apnea such as intra-oral devices. It further envisages that the center itself would provide CPAP therapy, thereby facilitating the tracking of CPAP compliance. For insomnia, outcomes would include an insomnia symptom questionnaire, sleep diary (could be web-based), medication use, etc. For other sleep disorders, there would also be specific outcomes. There need to be processes put in place to establish national guidelines for outcomes to be assessed for each sleep specific disorder.

While initially tracking outcomes will involve currently available technology, it will be facilitated by use of information technology. Technology could be employed to capture questionnaire information using web-based approaches or touch screens in outpatient offices and sleep laboratories. Information technology could be used to input other relevant clinical data and to track outcomes from devices such as PAP machines. Databases will need to be developed to store, track outcomes, and be the basis of graphical outputs as well as reports to the insurance carriers.

One of the barriers to developing information technology (IT) is that currently IT systems are propriety, with each manufacturer of diagnostic equipment or therapeutic equipment doing “their own thing.” Our profession needs to provide guidance about our needs with the hope that all stakeholders will see benefit in collaborating and moving out of their silos.

Cost-effective chronic disease management of large numbers of patients requires the focus and expertise of all professions. Particularly important in this regard are nurse practitioners trained in sleep medicine. The School of Nursing at the University of Pennsylvania has taken the lead in developing a training program in this area. The benefit of a nurse-led treatment program for sleep apnea has already been demonstrated in a randomized trial in Australia.6

This model envisages that chronic management of patients with sleep disorders will be under the guidance of a sleep medicine physician. Some have argued that this should be the purview of the internist or family medicine practitioner.4 While this may be viable in the future, our own experience suggests that this is not something that the internist/family practitioner wants to take on, at least at present. They have difficulty managing the vast array of daily needs presented by their patients, resulting in major time pressures. Currently Penn is experimenting with placing our sleep medicine physicians as “embedded specialists” in the community-based internal medicine practices totally owned by the University of Pennsylvania (Clinical Care Associates). We envisage nurse practitioners trained in sleep medicine also practicing in these locations. Telemedicine/web-based approaches should be developed that assist in patient follow-up and tracking outcomes. This can be conducted in the patient's home, without the need for the patient to travel, park, and wait to see the physician or nurse practitioner.

While currently this brave new world is a dream, it all does not need to be accomplished at once. We do, however, need to take action on initial steps to make our field an outcomes-based field with innovative approaches to tracking outcomes, with currently available technology. We need to start with consensus on best practices, since much of this lacks a formal evidence base. There is, however, a wonderful opportunity to develop research programs in comparative effectiveness research to formally evaluate different strategies. This will require collaboration between academic medical centers, community-based practices and involve all stakeholders including insurance carriers and patients. As results of this research become available, diagnostic and treatment strategies can be modified and upgraded. It is a major opportunity for a partnership between our academic and clinical colleagues.

Thus, the fundamental themes of this commentary are the following: a) change in sleep medicine is essential and the time is now; b) the American Academy of Sleep Medicine needs to take the lead in indicating the urgency of the situation, based on the sub-optimal Massachusetts experience; c) the vision for our field should be a quality outcomes-based chronic disease management discipline for all sleep disorders, not just for sleep apnea; d) the American Academy of Sleep Medicine should lead change and use the power of the accreditation process to move our field to a quality outcomes field. It is time to be proactive, not reactive; and e) there is a need for all stakeholders to work together to develop the information technology we need.

The time is NOW. It is time to act. Groups who act can lead the change in the best interest of the people we serve, i.e., the millions of Americans with chronic sleep disorders.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Dr. Pack has indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to John Leteria (CEO of Neurocare, Inc.), Dr. Michael Coppola and Dr. Larry Epstein for information about what has happened in Massachusetts and Kim Halscheid, Education Coordinator in the Sleep Division at the University of Pennsylvania for pointing out to me the article on leading change.

CITATION

Pack AI. Sleep medicine: strategies for change. J Clin Sleep Med 2011;7(6):577-579.

REFERENCES

- 1.Strollo PJ., Jr Embracing change, responding to challenge, and looking toward the future. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:312–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotter JP. Leading change--why transformation efforts fail. Harv Bus Rev. 2007 Jan;:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colten HR, Altevogt BM. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavie P. Sleep medicine-time for a change. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrisroe P. Wide awake: what I learned about sleep from doctors, drug companies, dream experts, and a reindeer herder in the Arctic Circle. Spiegel & Grau; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antic NA, Buchan C, Esterman A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of nurse-led care for symptomatic moderate-severe obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:501–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1558OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]