Abstract

We report here on the interrelationship of aggressive behaviour and thermoregulation in honeybees. Body temperature measurements were carried out without behavioural disturbance by infrared thermography. Guard bees, foragers, drones, and queens involved in aggressive interactions were always endothermic, i.e. had their flight muscles activated. Guards made differential use of their endothermic capacity. Mean thorax temperature was 34.2–35.1°C during examination of bees but higher during fights with wasps (37°C) or attack of humans (38.6°C). They usually cooled down when examining bees whereas examinees often heated up during prolonged interceptions (maximum >47°C). Guards neither adjusted their thorax temperature (and thus flight muscle function and agility) to that of examined workers, nor to that of drones, which were 2–7°C warmer. Guards examined cool bees (<33°C) longer than warmer ones, supporting the hypothesis that heating of examinees facilitates odour identification by guards, probably because of vapour pressure increase of semiochemicals with temperature. Guards in the core of aggressive balls clinged to the attacked insects to fix them and kill them by heat (maximum 46.5°C). Bees in the outer cluster layers resembled normal guards behaviourally and thermally. They served as active core insulators by heating up to 43.9°C. While balled wasps were cooler (maximum 42.5°C) than clinging guards balled bees behaved like examinees with maximum temperatures of 46.6°C, which further supports the hypothesis that the examinees heat up to facilitate odour identification.

Introduction

Honeybees (Apis sp.) are heterothermic insects with the ability of intense endothermy. They are endothermic not only during the whole foraging cycle (e.g. Esch 1960; Heinrich 1979a, 1993; Schmaranzer & Stabentheiner 1988; Stabentheiner & Hagmüller 1991; Stabentheiner 1996a; Kovac & Schmaranzer 1996; Schmaranzer 2000) but also during guarding activity (Stabentheiner et al. 2002), and during attack of insect enemies (Esch 1960; Ono et al. 1987, 1995; Stabentheiner 1996b; Kastberger & Stachl 2003; Ken et al. 2005) and of large mammalian predators (Heinrich 1979a). As body temperature measurements on aggressive bees are still rare, we provide here a detailed overview and analysis of the behaviour of different honeybee castes of Apis mellifera carnica during aggressive interactions of different kinds from a thermal point of view. Standard thermometry is critical if it is to investigate the interrelationship of behaviour and thermoregulation because killing or at least behavioural impairment is inevitable upon body temperature measurements with fine thermocouples, for instance. With infrared thermography, we were able to investigate the dynamics of thermoregulation without behavioural disturbance.

In detail, body temperature of guards and their examinees is of interest in the behavioural context on several grounds. Guards were reported to decrease rather (but not always) than increase thorax temperature during longer lasting examinations, whereas examinees showed both thoracic cooling and intense heating bouts (Stabentheiner et al. 2002). A high thorax temperature increases flight muscle performance and thus readiness for takeoff (Esch 1976, 1988; Coelho 1991) and general agility (Stabentheiner et al. 2003b). For the guards one might suggest, therefore, that they adjust their flight muscle temperature to that of their examinees to increase the own agility when the examinees heat up or to save energy if they cool down. We present here a detailed analysis of the guard bees’ thorax temperature in relation to that of the examined workers.

Guards can discriminate nestmate drones from non-nestmates as well as workers (Kirchner & Gadagkar 1994). Drones are larger than guard bees and by several degrees warmer during landing at the hive entrance (Coelho 1991; Kovac & Stabentheiner 2004). This raised the question of whether guards have a higher body temperature when inspecting drones to compensate for the drones’ greater strength and higher body temperature.

Guarding and division of labour during colony defence is known to be in part genetically determined (Robinson & Page 1988; Breed et al. 1995, 2004). When guards examine bees, however, not only genetically determined gland components and cuticular hydrocarbon profiles play a role but also cues derived from the colony (hive odours) (Moore et al. 1987; Breed & Julian 1992; Arnold et al. 1996; Breed 1998; Downs & Ratnieks 1999; Fröhlich et al. 2000; Wakonigg et al. 2000; Breed et al. 2004; Dani et al. 2005; D’Ettorre et al. 2006; Schmitt et al. 2007). Stabentheiner et al. (2002) reported that thoroughly examined bees often heat up their thorax considerably. It was hypothesized that they do this to enhance chemical signalling via an increase in vapour pressure of chemicals from their surface involved in nestmate recognition. If this was the case the time guards spend to identify a bee should depend on the examined bee’s body temperature. We provide here data that support this hypothesis.

The honeybee queen is usually not aggressive against other bees. Exceptions are fights with other young queens, and the attack of their cells before they emerge (Ruttner 1980; Gilley 2001; Pflugfelder & Koeniger 2003). We report here the body temperature of a young queen during a rare event, the attack of a queen cell, and compare it with that during normal hive duties.

Wasps are particularly dangerous enemies of honeybees, having a head start on bees not only because of their sting but also due to their strong mandibles. They often assail honeybees directly. Nevertheless guards often attack them at the nest entrance. As flight muscle temperature may be important during fights we investigated whether fighting guards increase their thorax temperature above the level during guarding. These measurements are compared with the temperature during flight attack (stinging) of large mammalian enemies (authors).

Both wasps and bees of strange colonies are known to intrude into bee colonies to rob their honey. When guard bees are not able to defend such intruders alone they recruit other bees to help them (Ono et al. 1987). During such mass attacks they increase their thorax temperature in an attempt to kill the engulfed insects by heat (Esch 1960; Ono et al. 1987, 1995; Stabentheiner 1996b; Kastberger & Stachl 2003; Ken et al. 2005). We report here the body temperature of A. mellifera bees clustering wasps and other bees during unprovoked occurrence of this phenomenon in relation to their behaviour, and report direct body temperature measurements of the engulfed insects.

Methods

Guarding behaviour can be observed at the nest entrance as well as inside a colony (Butler & Free 1952). Therefore, body temperature measurements of guards and examined workers and drones were made at various locations around Graz from 1989 to 2006 in observation hives (3000–6000 bees) which were covered by infrared transmissive plastic foils, or at the entrance of standard colonies of A. mellifera carnica (15 000–30 000 bees) located in an apiary. For comparison, workers and drones leaving the colony and returning to it were thermographed at the entrance of standard colonies. Thermally aggressive bee balls against wasps and bees were thermographed during natural, unprovoked occurrence on the combs of observation hives. Fights between bees and wasps were thermographed during natural occurrence within 1 m of the hive entrance. Bees attacking humans were provoked at the entrance of standard colonies by means of a leather glove and thermographed within 5–10 m of the colony when they tried to sting the glove or the authors. Queens were thermographed during normal hive duties, and on alert because of an introduced queen cell in observation hives.

Thermographic measurements of honeybee and wasp body surface temperature were done in real time with an AGA 782 SW or a ThermaCam SC2000 NTS thermographic system (FLIR, Inc., Danderyd, Sweden) which both have a sensitivity of 0.1°C. Temperature was calibrated to the nearest 0.7°C using an infrared emissivity of 0.97 of the insect cuticle (Stabentheiner & Schmaranzer 1987; Kovac & Stabentheiner 1999) and calibrated reference sources (AGA 1010 or self-constructed peltier-driven) of known temperature and emissivity. Air temperature near the bees was measured by means of thermocouples inside the hive and thermistor thermoprobes or thermocouples at the hive entrance. Temperature data were read directly from thermocouple thermometers (Testo, Wein, Austria) or stored with Almemo data loggers (Ahlborn, Holzkirchen, Germany), and in the latter case automatically extracted from the logger files during temperature evaluation. The bees’ behaviour was judged from the thermographic sequences which were stored on video tape (AGA 782 SW) or digitally on computer (ThermaCam SC2000).

Statistics were performed with the Statgraphics package (StatPoint, Inc., Herndon, VA, USA) or with self written Excel sheets (Microsoft Corporation, Redmont, WA, USA) according to Sachs (1997). Correlations were calculated with Statgraphics or ORIGIN (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). For chi-squared statistics, the significance level was adjusted according to the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons wherever applicable (Sachs 1997).

Results

Individual Interactions

In guards, the transition from simple (short) contacts to truly aggressive examinations was fluid. During short contacts of <1 s duration examinees often did not stop. The guards touched them only shortly with their antennae. Longer lasting examinations could proceed at a more leisurely pace or go up to intense movements of the guards around the examinee. Then the guards made contact with the examinees with their antennae or even mouthparts. The examinees stood on their four hind legs and exposed their tergal glands. After some time, they extruded their proboscis and displayed self-grooming of mouthparts and head (compare Butler & Free 1952). The mouthpart temperature resembled the head temperature before the first guard arrived but usually decreased some seconds later because of evaporation of extruded fluid. In some bees, the mouthparts were cool throughout examination (Fig. 1a) whereas in others this could not be proofed for the whole examination period (Fig. 1b). When guards lost their interest in the examined workers after some time, they often were relieved by other guards (Fig. 1). Despite often very intense examinations, stinging of examinees by guards was observed in only one out of several hundreds of observed interactions.

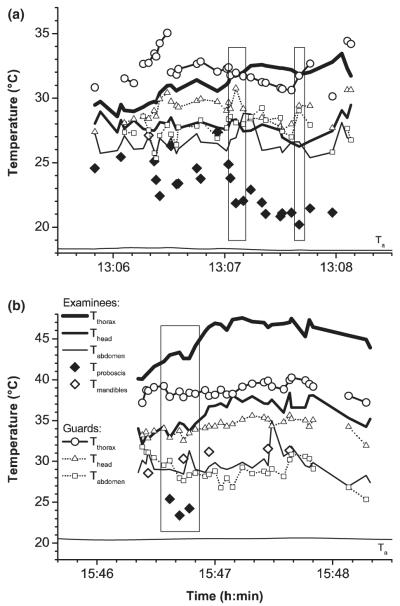

Fig. 1.

Body surface temperatures of a cool (a) and a hot examinee (b) where the wet (=cool) proboscis was visible in the infrared images (measured with a close-up lens at the hive entrance). Rectangles, comparison of head temperatures (see text); Ta = ambient air temperature.

A detailed analysis of the relationship of the body temperature of guards and their examinees was performed at the hive entrance. Workers being contacted by guards only shortly (<1 s) had nearly the same thorax surface temperature (35.5°C) than the guards inspecting them (35.1°C) or other bees landing at the hive entrance (35.2°C; Table 1). On average the examinees’ and the guards’ mean thorax temperatures decreased with increasing duration of the examinees’ interception by guards (all data). However, in thoroughly examined workers (duration of interception >30 s) the thorax temperature was on average considerably higher because of an increased occurrence of thoracic heating bouts (Fig. 1, Table 1). Therefore, only a weak positive correlation of guard thorax temperature (Tth) with that of examinees being intercepted for longer than 1 s was found (Tth guard = 28.68438 + 0.1416*Tth examinee; R = 0.24377, n = 1192 measurements, p < 0.0001). The thorax temperature of guards did not correlate with that of shortly (<1 s) contacted examinees (R = −0.0901, n = 153, p = 0.268).

Table 1.

Mean thorax surface temperatures of guard bees during examination of bees and attack of wasps and humans, and of examined work- ers, drones and attacked wasps at the hive entrance

| Surface temperature (°C) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insect | Thorax | Head | Abdomen | N | Ninsect | Ta (°C) |

| Workers | ||||||

| Workers shortly contacted (<1 s) | 35.5 ± 2.22 | 31.9 ± 1.90 | 30.3 ± 2.01 | 153 | 153 | 28.1 |

| Guards | 35.1 ± 1.74 | 31.5 ± 1.64 | 30.2 ± 1.77 | 153 | 50 | 28.1 |

| Workers briefly examined (>1–5 s) | 34.1 ± 2.24 | 31.6 ± 1.57 | 29.8 ± 1.97 | 140 | 50 | 28.3 |

| Guards | 34.8 ± 2.04 | 31.7 ± 1.79 | 30.3 ± 1.76 | 140 | 50 | 28.3 |

| Workers medium long examined (>5–30 s) | 33.9 ± 2.33 | 31.7 ± 1.70 | 30.8 ± 1.73 | 134 | 22 | 28.6 |

| Guards | 34.7 ± 2.05 | 32.1 ± 1.60 | 31.1 ± 1.60 | 99 | 25 | 28.6 |

| Workers thoroughly examined (>30 s) | 36.0 ± 4.19 | 31.9 ± 2.30 | 30.6 ± 2.00 | 761/759/759 | 46 | 28.3 |

| Guards | 34.2 ± 1.87 | 31.6 ± 1.56 | 30.6 ± 1.57 | 895/676/677 | 256 | 28.3 |

| Drones | ||||||

| Drones shortly contacted (<1 s) | 39.8 ± 2.80 | 35.2 ± 1.99 | 31.8 ± 1.56 | 40 | 40 | 21.0 |

| Guards | 33.7 ± 3.04 | 30.9 ± 1.93 | 29.5 ± 2.20 | 40/40/39 | 40 | 21.0 |

| Drones briefly examined (>1–5 s) | 41.5 ± 1.52 | 36.9 ± 1.68 | 33.2 ± 1.76 | 23/14/14 | 8 | 22.1 |

| Guards | 34.6 ± 3.51 | 32.9 ± 1.48 | 29.4 ± 2.38 | 23/14/13 | 8 | 22.1 |

| Drones medium long examined (>5–30 s) | 37.4 ± 4.52 | 34.6 ± 1.65 | 30.5 ± 0.54 | 53/6/6 | 14 | 23.6 |

| Guards | 31.5 ± 2.15 | 30.3 ± 1.48 | 29.2 ± 0.82 | 54/6/4 | 14 | 23.6 |

| Drones thoroughly examined (>30 s) | 38.0 ± 3.55 | 29.5 ± 1.62 | 28.2 ± 0.92 | 56/4/4 | 6 | 23.7 |

| Guards | 34.6 ± 4.56 | 27.4 ± 1.44 | 27.8 ± 1.35 | 56/4/4 | 6 | 23.7 |

| Landing and takeoff | ||||||

| Foragers landing | 35.2 ± 2.52 | 30.8 ± 2.12 | 22.8 ± 1.61 | 218/168/168 | 218 | 21.6 |

| Foragers takeoff | 36.4 ± 3.04 | 32.3 ± 1.81 | 31.6 ± 1.19 | 219/169/169 | 219 | 21.6 |

| Drones landing | 38.1 ± 1.22 | 34.1 ± 1.52 | 24.7 ± 1.37 | 232 | 232 | 20.4 |

| Drones takeoff | 40.7 ± 1.83 | 36.0 ± 1.15 | 32.8 ± 1.09 | 328/278/278 | 328 | 21.9 |

| Fights | ||||||

| Wasps attacked | 30.9 ± 2.57 | 61 | 5 | 27.3 | ||

| Guards attacking wasps | 37.0 ± 4.40 | 105 | 8 | 27.3 | ||

| Guards attacking humans | 38.6 ± 3.32 | 31.1 ± 3.44 | 24.9 ± 3.09 | 43/40/43 | 22 | 17.9 |

| Inside colony | ||||||

| Workers examined on combsa | 42.2 ± 0.95 | 587 | 34 | 31.1 | ||

| Guards on combsa | 36.6 ± 0.53 | 702 | 45 | 31.1 | ||

For comparison, temperatures of workers and drones landing and starting at the hive entrance are provided.

Values are given as x ± SD.

Ta = ambient air temperature.

To elucidate the question of whether guards tune their thorax temperature to that of their examinees, we analysed the development of their thorax temperature during contact in detail. Many guards cooled down despite intense heating bouts of the examinees but some kept the thorax temperature approximately constant or even heated up (Fig. 1; see also Stabentheiner et al. 2002). Their temperature change from the start until the end of their contact with the examinees followed the regression dTth (°C) = −0.26102 − 0.01481*duration (s) (R = −0.3596, n = 140 guards, p < 0.0001; range −6.4°C to +4.2°C). Despite a large scatter of dTth of the examinees (−4°C to +11.7°C) there was a weak positive correlation with the contact duration (dTth = 0.10348 + 0.01852*duration; R = 0.2589, n = 140, p < 0.05). However, there was no correlation between the temperature changes of the guards with that of their examinees (R = 0.08821, n = 140, p = 0.30).

The guards also did not adjust their thorax temperature to the considerably higher temperatures of drones. Their thorax temperature was the same as or lower than of guards examining workers. The relationship of their body temperatures resembled that between drones and workers during landing and takeoff (Table 1). Examined drones differed not only thermally but also behaviourally from workers. They were less obsequious and more often tried to escape long lasting examinations by walking away or taking off despite heavy biting and tugging by the guards.

If guarding activity escalated into fights against wasps outside the hive, guards increased their thorax temperature to 37°C (Table 1). The combated wasps, by contrast, were much cooler (30.9°C). Bees attacking humans in flight were even warmer (38.6°C) despite an about 10°C lower ambient temperature in these measurements (Table 1).

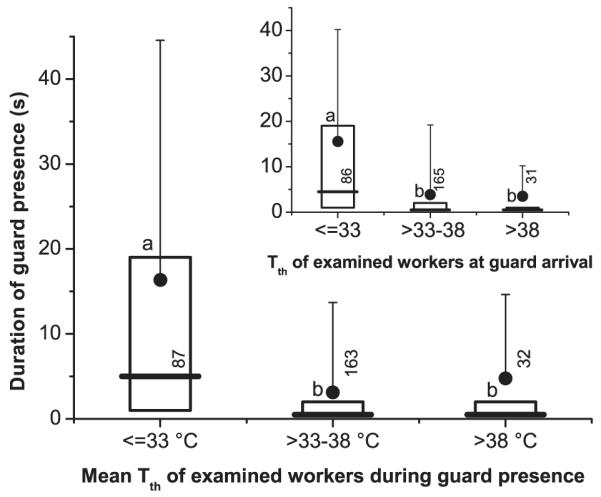

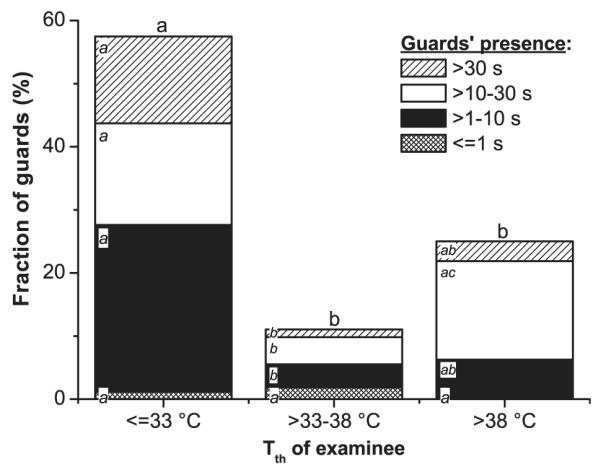

Body Temperature and Nestmate Recognition

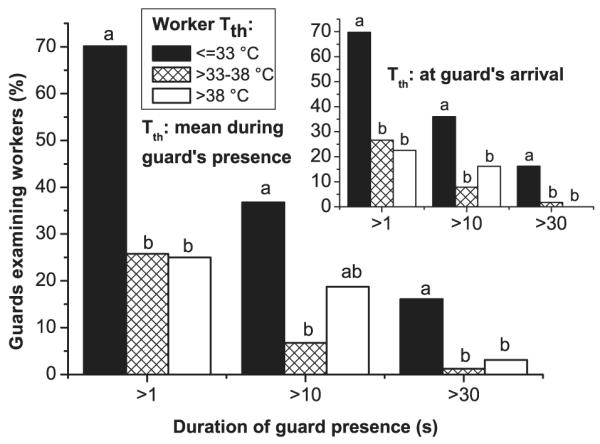

The time guards made contact with examined workers varied strongly, from short contacts (<1 s) to several minutes. To investigate the role of body temperature in the nestmate identification process, we analyzed the effect of the examinees’ thorax surface temperature (Tth) on the time the guards spent examining them. We divided the range of the examined workers’ thorax temperatures (27.8–43.3°C) in three classes, ≤33°C, 33–38°C, and >38°C. Guards examined cool workers with a Tth ≤33°C significantly longer (x 16.4 s/ 5 s) than warmer ones with a Tth of 33–38°C (3.1/0.5 s) or a Tth of >38°C (4.8/0.5 s; Fig. 2). Regression analysis showed that an exponential function (duration = e−7.1791+262.23/ Tth) describes the decrease of contact duration with increasing mean examinee thorax temperature considerably better (R = 0, 41648; p < 0.00001; see also legend of Fig. 2) than a linear one (R = −0.248329; p < 0.00001). This was mainly caused by a significantly higher proportion of long examinations at low examinee temperature, reflected by a higher standard deviation (Fig. 2; p << 0.0001, Bartlett’s test), and a higher percentage of guards examining bees for longer than a certain period (Fig. 3). The bees with medium (33–38°C) or high thorax surface temperature (>38°C) did not differ from each other (Figs 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Time guards spent examining worker bees at the hive entrance (bold horizontal lines and boxes: with quartiles 1 and 3; dots and vertical lines: x with SD) in dependence on the examinees’ mean thorax surface temperature (Tth) during the guards’ presence (main graph), and in dependence on the examinees’ Tth at the time of the guards’ arrival (insert). Numbers = guards. Different letters (a, b) denote significant differences of medians (p < 0.05; U-test). Variation of data siginificantly higher in lowest temperature class in main graph, and in two lower classes in insert (p < 0.05, Bartlett’s test). Main graph: duration = e−7.1791+262.23/ Tth (R = 0.41648; p < 0.00001). Insert: duration = e−8.0684+292.16/ Tth (R = 0.463346; p < 0.00001).

Fig. 3.

Proportion of guards examining worker bees at the hive entrance for longer than 1, 10 or 30 s, in dependence on the examinees’ mean thorax surface temperature (Tth) during the guards’ presence (main graph), and in dependence on the examinees’ Tth at the time of the guards’ arrival (insert). Different letters (a, b) denote significant differences (p < 0.05; Bonferroni chi-squared test). No difference between columns of main graph and insert. Main graph: 100% = 87/163/32 bees, and insert: 100% = 86/165/31 bees for the three temperature classes, respectively.

The probability of the guards to examine bees with the proboscis wet already before or sometime during their presence, indicating the chance for them to sense pheromone secretions from the examinees’ head glands which might play a role during identification, was highest with the coolest examinees even though the proboscis was usually dry when the first guard arrived at an examinee (Fig. 4). Again, the bees with medium (33–38°C) or high thorax surface temperature (>38°C) did not differ from each other.

Fig. 4.

Fraction of guards examining bees at the hive entrance which had their mouthparts wet before the guards’ arrival or sometime during examination, in dependence on the examinees’ mean thorax surface temperature (Tth) during the guards’ presence. Different letters (a, b, c) denote significant differences between total columns and sub-columns (p < 0.05, Bonferroni chi-squared test). 100% = 87/163/32 bees for the three temperature classes.

Queen

Honeybee queens were predominantly ectothermic (body parts at similar temperatures) during normal hive activities like egg-laying and patrolling (Table 2). They moved not or only slowly and, with the exception of their attendants, did not care much about their workers.

Table 2.

Body surface temperatures of queens and workers near them during different behaviours

| Body surface temperature (°C) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bees | Activity, location | Head | Thorax | Abdomen | Ta (°C) |

| Young queen | |||||

| Queen alerta | On queen cell | 37.5 ± 0.68/215, 1 | 39.4 ± 0.96/217, 1 | 36.0 ± 0.71/196, 1 | 32.8 |

| Tooting on queen cell | 38.1 ± 0.53/8, 1 | 40.0 ± 0.76/8, 1 | 36.0 ± 0.46/8, 1 | 32.6 | |

| Biting queen cell | 37.7 ± 0.49/9, 1 | 39.4 ± 0.81/9, 1 | 35.9 ± 0.20/9, 1 | 32.8 | |

| Walking off queen cell | 37.2 ± 0.75/50, 1 | 39.0 ± 0.98/50, 1 | 36.1 ± 0.72/50, 1 | 32.8 | |

| Workersa | On queen cell | 35.4 ± 1.48/70, 70 | 35.8 ± 1.87/70, 70 | 34.9 ± 0.96/70, 70 | 32.9 |

| Queen idleb | Idle off queen cell | 33.5 ± 0.72/19, 1 | 33.8 ± 0.72/19, 1 | 34.4 ± 1.07/19, 1 | 30.4 |

| Workersb | Attending | 35.9 ± 1.82/10, 10 | 37.6 ± 2.14/10, 10 | 33.9 ± 1.26/10, 10 | 31.4 |

| Adult queens | |||||

| Queen 1a | Idle | 31.0 ± 1.04/48, 1 | 31.0 ± 1.06/48, 1 | 31.1 ± 1.10/48, 1 | 30.7 |

| Laying | 31.6 ± 0.26/4, 1 | 31.9 ± 0.26/4, 1 | 31.9 ± 0.25/4, 1 | 32.2 | |

| Workersa | Attending | 31.2 ± 1.16/290, 115 | 30.8 | ||

| Queen 2b | Idle | 32.6 ± 0.68/29, 1 | 32.6 ± 0.73/29, 1 | 33.6 ± 0.74/29, 1 | 31.7 |

| Laying | 32.4 ± 0.32/10, 1 | 32.3 ± 0.18/10, 1 | 33.3 ± 0.45/10, 1 | 32.8 | |

| Workersb | Attending | 33.6 ± 1.14/41, 41 | 34.2 ± 1.60/41, 41 | 33.4 ± 0.77/41, 41 | 32.0 |

Values are given as x ± SD/N, Nbees.

Ta = air temperature near the bees.

Bees measured on 2 d.

Bees measured on 3 d.

However, when a freshly emerged queen discovered an accidentally introduced queen cell (after death of the old queen the new queen cell had not been detected) her behavioural pattern changed dramatically. She became agitated and patrolled much faster through the colony, even faster than observed in guards which examined several bees in succession inside the colony. Now she was endothermic whenever we observed her patrolling (Table 2). Staying on the queen cell, her behaviour resembled that of examining guards. During production of tooting sounds on the queen cell (Michelsen et al. 1986) the thorax temperature of our queen was highest (40°C). Workers on the queen cell, for comparison, were cooler on average (35.8°C). This alert state vanished only after several days (Table 2) when the second queen had emerged from her cell and probably was killed.

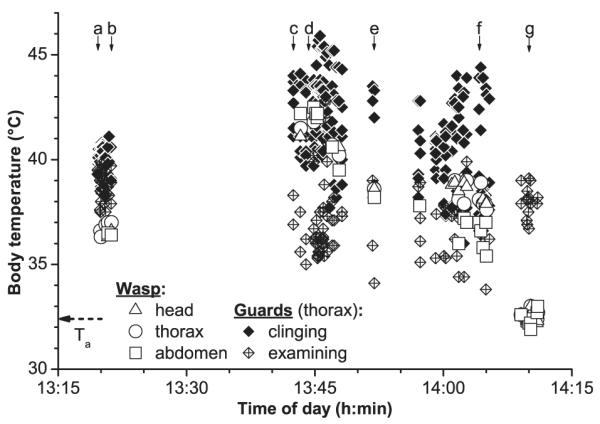

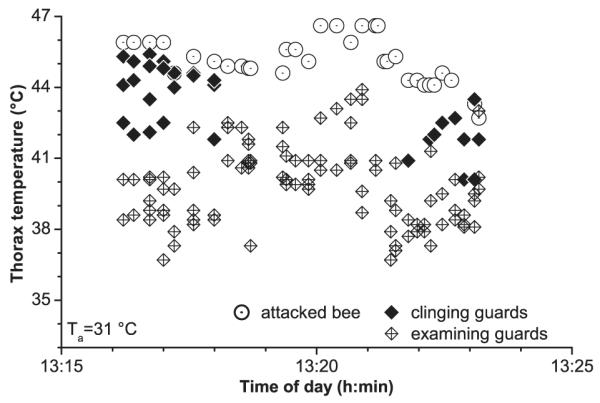

Social Aggression

Figures 5 and 6 show thermograms and the evaluated temperatures of a social attack (thermal cluster) of bees on a wasp (Paravespula sp.) that had intruded into the colony to rob the honey. In the beginning, the attacking bees had only a moderately heated thorax (39.3–39.8°C). Eventually, individual bees started to increase their thorax temperature above normal levels (Fig. 5b), the warmest bees reaching a temperature of 45.9°C (Figs 5d and 6). We observed behavioural differences between the clusters bees. The core bees clinged to the wasps and did not move much. They were the warmer ones (maximum temperature 45.9°C; Figs 6 and 7). These core bees were surrounded by a shell of bees which were moving more or less agitatedly, and many of them examined the cluster thoroughly as guard bees do when they inspect individual bees. They were cooler than the core bees.

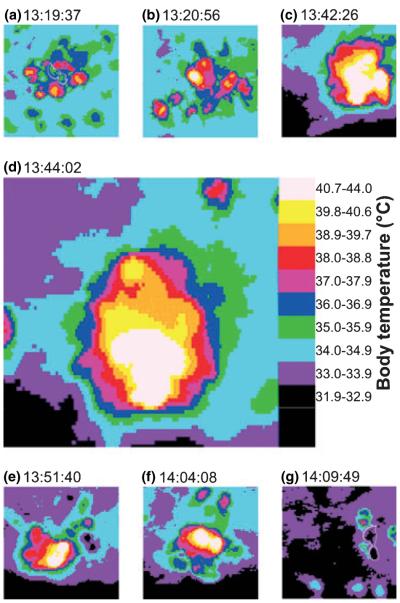

Fig. 5.

Infrared thermograms of honeybees during thermal attack (‘balling’) against a wasp (Paravespula sp.) from the beginning of the attack (a) until the time when the dead wasp was brought out of the colony by one of the guards (g). Wasp marked by white outlines in (a) and (g). For detailed temperature measurements at the time the thermograms were made see Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Body surface temperatures of honeybees during thermal attacks (‘balling’) against a wasp (Paravespula sp.). Letters a–g (with arrows) denote points in time where the thermograms in Fig. 5 were taken. Ta, air temperature near the cluster.

Fig. 7.

Body surface temperatures of honeybees during thermal attacks (‘balling’) against a bee. Ta, air temperature near the cluster.

The body temperature of the attacked wasp (marked with white outlines in Fig. 5a) was low in the beginning (36.3–36.9°C; about 4°C above ambient air temperature) and below that of the bees (ca. 37.5–40°C; Figs 5 and 6). During intense heat production, when the cluster size was greatest, it was heated to about 42.5°C but always remained cooler than the warmest of the clinging core bees. Another wasp was heated to similar temperatures (Table 3). When in the end one of the guards removed the corpse of the dead wasps the wasp thorax temperature (32.3–34°C) resembled that of the surrounding air (32.6–32.9°C) whereas the bees kept their thorax at 36.7–40.9°C (Figs 5 and 6; Table 3).

Table 3.

Body surface temperatures of guards and attacked insects in unprovoked balls of thermally aggressive bees inside an observation hive

| Guards in cluster |

Attacked insects |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thorax temperature (°C) |

Body temperature (°C) |

|||||||

| Cluster | Clinging | Inspecting | Corpse removal | Insect | Head | Thorax | Abdomen | Ta (°C) |

| 1 | 41.0 ± 2.04 (282)(36.0–45.9) |

37.4 ± 1.67 (119)(33.8–42.8) |

Wasp alive |

36.1 ± 3.18 (22)(32.2–41.1) |

36.6 ± 3.09 (28)(32.3–41.8) |

36.6 ± 3.59 (28)(31.9–42.5) |

32.4 | |

| 38.0 ± 0.71 (16)(36.7–39.1) |

Wasp dead |

32.5 ± 0.26 (9)(32.2–33.0) |

32.6 ± 0.20 (9)(32.3–33.0) |

32.5 ± 0.28 (8)(32.2–33.0) |

32.6 | |||

| 2 | 44.2 ± 0.78 (81)(42.8–46.5) |

Wasp alive |

41.1 (1) | 41.9 ± 1.19 (4)(40.2–43.0) |

33.8 | |||

| 39.5 ± 1.56 (103)(35.2–43.8) |

39.7 ± 1.22 (14)(37.0–40.9) |

Wasp dead |

33.6 ± 0.28 (10)(33.1–34.0) |

32.9 | ||||

| 3 | 42.1 ± 1.99 (74)(35.6–44.8) |

38.9 ± 1.29 (29)(37.3–42.6) |

Bee | 41.1 ± 0.93 (5)(39.7–42.3) |

44.6 ± 0.46 (16)(43.5–45.4) |

41.7 ± 0.85 (2) (41.1–42.3) |

31.2 | |

| 4 | 43.2 ± 1.52 (32)(40.1–45.4) |

39.8 ± 1.63 (106)(36.7–43.9) |

Bee | 45.1 ± 0.97 (33)(42.7–46.6) |

31.0 | |||

Values are given as x ± SD (N) (min–max).

In another two thermogenic clusters no wasp could be found in the core. The attacked insects were bees (Fig. 7). They could easily be distinguished from the other bees by their behaviour which was equal to foragers being examined thoroughly by guards. However, not only their behaviour but also their thorax temperature was like that of examined foragers. They reached surface temperatures as high as 45.4 and 46.6°C, which was the same as or even higher than that of the warmest of the clinging bees (44.8–45.4°C; Fig. 7, Table 3). Such clusters were also observed several times against bees introduced from another colony and against an accidentally introduced queen when the old queen had died and the young queen had not been detected.

Discussion

Body Temperature and Agility During Guarding and Attack

In honeybees higher thorax temperatures result in a higher agility (Stabentheiner et al. 2003b), and function of flight muscles is temperature dependent (Esch 1976, 1988; Coelho 1991). In guards, this had raised the question of whether they adjust their thorax temperature to tune their state of alert or readiness for flight to that of their examinees. However, our detailed analysis of thorax temperature changes showed that guards do not react directly to changes of the examinees’ thorax temperature. When thoroughly examined bees start their heating bouts, newly arriving guards also cool down preferentially (Stabentheiner et al. 2002). Likewise, the guards do not increase their thorax temperature when they examine drones, which at the hive entrance are considerably warmer than workers (Table 1). The guards, therefore, seem not to ‘assume’ examinees to try to escape, which indeed happened scarcely. On the other hand, an even higher state of alert of guards for immediate takeoff may not be necessary because intruders anyway have to land to enter a colony. In the dense air traffic in front of a colony, it may be very difficult for guards to track and catch an escaped bee or wasp.

During fights with wasps, where guards are generally at a disadvantage because of the wasps’ strong mandibles, the guards increased their thorax temperature to 37°C whereas the wasps stayed rather cool (ca. 31°C). A high flight muscle temperature may be of advantage in attempts to escape a wasp or when (during an intense fight) the bees beat their wings in a way that wasp and bee move like a spinning top. When bees attack large (mammalian) predators in flight their thorax temperature is even higher (38.6°C at an ambient temperature of 17.9°C), which increases to 40°C at 28°C (Heinrich 1979a). Such a high thorax temperature guarantees optimum flight performance (Esch 1976, 1988; Coelho 1991) for fast and goal-directed attack.

The intensity of examinations by guards varied, proceeding at a more leisurely pace or escalating into intense movements of the guards around the examinees. A high level of aggression, however, is not always visible as intense motion. The clinging bees in the core of a cluster (Figs 5–7) were highly aggressive and had intense muscular activity for the purpose of heat production despite a very low intensity or absence of movements. Locomotor activity and endothermy, therefore, are obviously independently adjustable parameters. A higher body temperature just increases the bees’ ability to move or fly fast (Stabentheiner et al. 2003b). A comprehensive definition of activity in bees, therefore, includes the ‘thermal behaviour’ (‘Temperaturverhalten’, Esch 1960), i.e. the muscular activity for the purpose of heat production.

Honeybee queens are ectothermic during normal hive activities like egg-laying and patrolling (Table 2), and in winter clusters (Stabentheiner et al. 2003a). This ectothermic state always coincides with slow movements. Our case report on an alert queen demonstrates that queen excitation results in endothermy, like in workers. We suggest that heating was a preparation for a fight with the other queen. The heated thorax was not a preparation for mating flights (although queens surely heat up in flight preparation) because we observed the queen patrolling excitedly through the hive for hours on several days. This occurred even in the morning when queens do not make mating flights because no drones are out.

Nestmate Recognition

Stabentheiner et al. (2002) suggested that body temperature plays a role in nestmate recognition of honeybees in a way that higher temperatures enhance chemical signalling. This was concluded from the observation that about 60% of thoroughly examined bees showed thoracic heating bouts (Fig. 1). Figures 2 and 3 provide support for this hypothesis. If the examinee’s thorax temperature is high, guards indeed spend less time at an examinee, and the percentage of guards inspecting such high-temperature examinees is lower. This may be even more helpful inside a colony where identification by odour may be hampered by high levels of hive odours (Breed et al. 1995, 2004; Breed 1998). The bees we observed inside aggressive clusters (Fig. 7) additionally support the ‘temperature dependence of identification’ hypothesis. Both their behaviour and their high body temperature resembled that of thoroughly examined foragers (Stabentheiner et al. 2002). It seems not conceivable that they heated up even higher than the clinging guards to ‘fight back’ by heat. Rather, we suggest that they did not know what was happening to them and went into a standard behavioural programme typical for intense examination, including intense thoracic heating to improve identification. If the improvement of chemical signalling by the examinees’ heating bouts works via an increase in vapour pressure of cuticular hydrocarbons alone, the whole blend of hydrocarbons found in the headspace of foraging bees up to Nonacosane (C29; Schmitt et al. 2007) may be relevant. If in addition, as discussed in Dani et al. (2005), phase transitions from solid to liquid also play a role those hydrocarbons that have their melting point in the range of the body surface temperature of foragers might be especially important (approx. 28–45°C; Heinrich 1979a; Stabentheiner & Schmaranzer 1987; Kovac & Schmaranzer 1996, Stabentheiner et al. 2002; Table 1). From the alkanes in the bees’ headspace this are chain lengths from C19 to C21 (melting points: 32, 36.7 and 40.2°C), and from the alkenes only C23:1 (melting point: approx. 40°C; C21:1, C22:1 and C24:1 were not found in the headspace by Schmitt et al. 2007). Such phase changes are also discussed in different insects concerning sudden changes of the cuticular permeability for water vapour (Beament 1959; Benoit & Denlinger 2007).

Michelsen (1993) and W. H. Kirchner (pers. comm.) reported that they constructed a variant of their robot bee (Michelsen et al. 1989, 1992) with built-in heating elements to test whether this could improve acceptance by hive bees because dancing foragers are always endothermic (Schmaranzer 1983; Stabentheiner & Hagmüller 1991; Stabentheiner et al. 1995; Stabentheiner 1996a, 2001). To their surprise, the model released fierce attacks by the bees each time its temperature exceeded 34°C. The present results may provide an explanation for this unexpected finding. As the robot bee was made of brass coated by a layer of beeswax, the hive bees probably could better identify the heated model by odour as strange. This released the attacks. Coating such a robot bee with the test colony’s wax and endowing it with cuticular wax extracts will probably improve acceptance.

Thoroughly examined bees regularly show auto-grooming with often cool (and thus wet) mouthparts (usually the proboscis, Fig. 1). Based on the experiments of Heinrich (1979b), Stabentheiner et al. (2002) had suggested that one purpose (beside others) of the often wet proboscis might be to cool the head during intense heating bouts. Figure 1 demonstrates that there is a cooling effect. Although guard and examinee had a similar thorax surface temperature as shown in Fig. 1a (see rectangles there), the dorsal head surface (between the ocelli) of the examinee was by several degrees cooler than in the guard. In Fig. 1b (rectangle), the head temperatures were similar despite a considerably higher thorax temperature of the examinee. Nevertheless, as the mouthparts very often become wet before thoracic heating starts and wet mouthparts are common in cool bees (Figs 1 and 4) an additional purpose of the regurgitated fluid has to be expected. The intercepted bees may regurgitate nectar to appease the guards (beg for entrance), or they may wet their mouthparts to facilitate identification by substances from e.g. head glands (Shearer & Boch 1965; Boch & Shearer 1967; Whiffler et al. 1988) which would in part be distributed over the head by the auto-grooming movements. Thoracic heating always increases the head temperature (Table 1; Schmaranzer & Stabentheiner 1988; Kovac & Schmaranzer 1996, Schmaranzer 2000) and this way increases the vapour pressure of any chemical there (Dykyj et al. 2000; Stabentheiner et al. 2002).

Social Aggression

Wasps attacking bees or invading their nest to rob their honey are a nuisance for them, especially, when the wasp colonies reach their maximum strength in late summer and early autumn. Our observation of thermal balling resembles a report of Esch (1960) in A. mellifera carnica. Several bees introduced into an observation hive with fine thermocouples glued on the thorax were attacked by the hive bees and eventually engulfed in balls. Ball temperature increased up to 45°C. Esch (1960) had assumed that it were the attacking bees that caused this temperature increase. Our body temperature measurements show that probably both the attacking and the attacked bees contributed to the temperature increase (Fig. 7). Ono et al. (1987, 1995) were the first to describe the natural occurrence of this behaviour, in Apis cerana, both inside and outside the colony. However, naturally formed balls are a rare event outside A. mellifera colonies, although they can be provoked experimentally (Ken et al. 2005). During many years of scientific work with honeybees and beekeeping, we observed balling in A. mellifera carnica against wasps and worker bees (Stabentheiner 1996b), drones and introduced queens inside colonies but never saw it to occur outside naturally. Because of intense predator pressure A. cerana makes more use of this defensive strategy (Ono et al. 1987, 1995), with higher core temperatures and more bees in the balls than A. mellifera (Ken et al. 2005). Apis cerana bees often reduce foraging activity if an attacking wasp is noticed, which is not the case in A. mellifera (Ono et al. 1995; Ken et al. 2005). The observation that defence by heat may also be directed against members of the own species (Fig. 7, Table 3) shows that it is a general strategy in social defence of insect enemies. The observation of thermal balling in Apis dorsata (Kastberger & Stachl 2003) suggests that it is an old property of honeybees, developing before speciation in the Apis genus.

By the use of real-time infrared thermography, we observed that both the thermal and the locomotor behaviour differ between different cluster parts. Intensive heat production occurs only in the core bees clinging to the combated insects (Figs 6 and 7), which applies the heat directly to the target. The absence of movements reduces convection and contributes to an efficient use of the heat. The bees surrounding the core are an active insulating layer in so far as their heated thoraces reduce the thermal gradient. This way they actively conserve the heat of the core bees because it is only the heat of the clinging bees that kills. The insulating layers of honeybee winter clusters, by contrast, reduce endothermy to a minimum to prevent heat loss (Stabentheiner et al. 2003a). Lethal temperatures of different wasp species attacked via thermal balling are in the range of 44–46°C (Ono et al. 1987, 1995; Ken et al. 2005). Our attacked wasps did not reach this level (Fig. 6, Table 3) but we suggest that they were warmer during times of maximal heating when the balls were too dense to identify them properly in the thermograms.

In conclusion, it can be said that during aggression, honeybees are always endothermic. During different types of aggressive interactions, they make differential use of their high endothermic capacity.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the help with electronics and software by G. Stabentheiner, with electronics by S. K. Hetz, for supply with a queen cell by N. Hrassnigg, and for helpful comments to editor and referees. Supported by the Austrian Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung (FWF; P13916 and P16584), and the Austrian Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Umwelt und Wasserwirtschaft.

Literature Cited

- Arnold G, Quenet B, Cornuet JM, Masson C, de Schepper B, Estoup A, Gasqui P. Kin recognition in honeybees. Nature. 1996;379:498. [Google Scholar]

- Beament JWL. The waterproofing mechanism of arthropods I. The effect of temperature on cuticle permeability in terrestrial insects and ticks. J. Exp. Biol. 1959;36:391–422. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit JB, Denlinger DL. Suppression of water loss during adult diapause in the northern house mosquito, Culex pipiens. J. Exp. Biol. 2007;210:217–226. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch R, Shearer DA. 2-Heptanone and 10-Hydroxy-trans-dec-2-enoic acid in the mandibular glands of worker honey bees of different ages. Z. Vergl. Physiol. 1967;54:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Breed MD. Chemical cues in kin recognition: criteria for identification, experimental approaches, and the honey bee as an example. In: Vander Meer RK, Breed MD, Espelie KE, Winston ML, editors. Pheromone Communication in Social Insects. Westview Press; Boulder: 1998. pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Breed MD, Julian GE. Do simple rules apply in honey-bee nestmate recognition? Nature. 1992;357:685–686. [Google Scholar]

- Breed MD, Garry MF, Pearce AN, Bjostad L, Hibbard B, Page RE. The role of wax comb in honeybee nestmate recognition: genetic effects on comb discrimination, acquisition of comb cues by bees, and passage of cues among individuals. Anim. Behav. 1995;50:489–496. [Google Scholar]

- Breed MD, Guzmán-Novoa E, Hunt GJ. Defensive bahavior of honey bees: organization, genetics, and comparisons with other bees. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2004;49:271–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler CG, Free JB. The behaviour of worker honeybees at the hive entrance. Behaviour. 1952;4:262–292. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho JR. The effect of thorax temperature on force production during tethered flight in honeybee (Apis mellifera) drones, workers, and queens. Physiol. Zool. 1991;64:823–835. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ettorre P, Wenseleers T, Dawson J, Hutchinson S, Boswell T, Ratnieks FLW. Wax combs mediate nestmate recognition by guard honeybees. Anim. Behav. 2006;71:773–779. [Google Scholar]

- Dani FR, Jones GR, Corsi S, Beard R, Pradella D, Turillazzi S. Nestmate recognition cues in the honey bee: differential importance of cuticular alkanes and alkenes. Chem. Senses. 2005;30:477–489. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bji040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs SG, Ratnieks FLW. Recognition of conspecifics by honeybee guards uses nonheritable cues acquired in the adult stage. Anim. Behav. 1999;58:643–648. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykyj J, Svoboda J, Wilhoit RC, Frenkel M, Hall KR. In: Landolt-Börnstein: Numerical Data and Functional Relationships in Science and Technology, Group IV: Physical Chemistry. CD-ROM edn Hall KR, editor. Vol. 20: Vapor Pressure of Chemicals. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Esch H. Über die Körpertemperaturen und den Wärmehaushalt von Apis mellifica. Z. Vergl. Physiol. 1960;43:305–335. [Google Scholar]

- Esch H. Body temperature and flight performance of honey bees in a servomechanically controlled wind tunnel. J. Comp. Physiol. 1976;109:254–277. [Google Scholar]

- Esch H. The effects of temperature on flight muscle potentials in honeybees and cuculiinid winter moths. J. Exp. Biol. 1988;135:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich B, Riederer M, Tautz J. Comb-wax discrimination by honeybees tested with the proboscis extension reflex. J. Exp. Biol. 2000;203:1581–1587. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.10.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley DC. The behaviour of honey bees (Apis mellifera ligustica) during queen duels. Ethology. 2001;107:601–622. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich B. Thermoregulation of African and European honeybees during foraging, attack, and hive exits and returns. J. Exp. Biol. 1979a;80:217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich B. Keeping a cool head: honeybee thermoregulation. Science. 1979b;205:1269–1271. doi: 10.1126/science.205.4412.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich B. The Hot-Blooded Insects, Strategies and Mechanisms of Thermoregulation. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kastberger G, Stachl R. Infrared imaging technology and biological applications. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comp. 2003;35:429–439. doi: 10.3758/bf03195520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ken T, Hepburn HR, Radloff SE, Yusheng Y, Yiqiu L, Danyin Z, Neumann P. Heat-balling wasps by honeybees. Naturwissenschaften. 2005;92:492–495. doi: 10.1007/s00114-005-0026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner WH, Gadagkar R. Discrimination of nestmate workers and drones in honeybees. Insectes Soc. 1994;41:335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Kovac H, Schmaranzer S. Thermoregulation of honeybees (Apis mellifera) foraging in spring and summer at different plants. J. Insect Physiol. 1996;42:1071–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Kovac H, Stabentheiner A. Effect of food quality on the body temperature of wasps (Paravespula vulgaris) J. Insect Physiol. 1999;45:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(98)00115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovac H, Stabentheiner A. Thermografische Messung der Körpertemperatur von abfliegenden und landenden Drohnen und Arbeiterinnen (Apis mellifera carnica Pollm.) am Nesteingang. Mitt. Dtsch. Ges. Allg. Angew. Entomol. 2004;14:463–466. [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen A. The transfer of information in the dance language of honeybees: progress and problems. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 1993;173:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen A, Kirchner WH, Andersen BB, Lindauer M. The tooting and quacking vibration signals of honeybee queens: a quantitative analysis. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 1986;158:605–611. [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen A, Andersen BB, Kirchner WH, Lindauer M. Honeybees can be recruited by means of a mechanical model of a dancing bee. Naturwissenschaften. 1989;76:277–280. [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen A, Andersen BB, Storm J, Kirchner WH, Lindauer M. How honeybees perceive communication dances, studied by means of a mechanical model. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1992;30:143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Moore AJ, Breed MD, Moor MJ. The guard honey bee: ontogeny and behavioural variability of workers performing a specialized task. Anim. Behav. 1987;35:1159–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Okada I, Sasaki M. Heat production by balling in the Japanese honeybee, Apis cerana japonica as a defensive behavior against the hornet, Vespa simillima xanthoptera (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) Experientia. 1987;43:1031–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Igarashi T, Ohno E, Sasaki M. Unusual thermal defence by a honeybee against mass attack by hornets. Nature. 1995;377:334–336. [Google Scholar]

- Pflugfelder J, Koeniger N. Fight between virgin queens (Apis mellifera) is initiated by contact to the dorsal abdominal surface. Apidologie. 2003;34:249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson GE, Page RE., Jr Genetic determination of guarding and undertaking in honey-bee colonies. Nature. 1988;333:356–358. [Google Scholar]

- Ruttner F. Apimondia Monigraphien. Apimondia Verlag; Bukarest: 1980. Königinnenzucht. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs L. Angewandte Statistik. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schmaranzer S. Thermovision bei trinkenden und tanzenden Honigbienen (Apis mellifera carnica) Verh. Dtsch. Zool. Ges. 1983;76:319. [Google Scholar]

- Schmaranzer S. Thermoregulation of water collecting honeybees. J. Insect Physiol. 2000;46:1187–1194. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(00)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaranzer S, Stabentheiner A. Variability of the thermal behavior of honeybees on a feeding place. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 1988;158:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt T, Herzner G, Weckerle B, Schreier P, Strohm E. Volatiles of foraging honeybees Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and their potential role as semiochemicals. Apidologie. 2007;38:164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer DA, Boch R. 2-Heptanone in the mandibular gland secretion of the honey-bee. Nature. 1965;206:530. [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner A. Effect of foraging distance on the thermal behavior of honeybees during dancing, walking and trophallaxis. Ethology. 1996a;102:360–370. [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner A. Thermische Aggression im Bienenvolk. Verh. Dtsch. Zool. Ges. 1996b;89.1:297. [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner A. Thermoregulation of dancing bees: thoracic temperature of pollen and nectar foragers in relation to profitability of foraging and colony need. J. Insect Physiol. 2001;47:385–392. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(00)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner A, Hagmüller K. Sweet food means ‘hot dancing’ in honeybees. Naturwissenschaften. 1991;78:471–473. [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner A, Schmaranzer S. Thermographic determination of body temperatures in honey bees and hornets: calibration and applications. Thermology. 1987;2:563–572. [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner A, Kovac H, Hagmüller K. Thermal behavior of round and wagtail dancing honeybees. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 1995;165:433–444. [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner A, Kovac H, Schmaranzer S. Honeybee nestmate recognition: the thermal behaviour of guards and their examinees. J. Exp. Biol. 2002;205:2637–2642. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.17.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner A, Pressl H, Papst Th., Hrassnigg N, Crailsheim K. Endothermic heat production in honeybee winter clusters. J. Exp. Biol. 2003a;206:353–358. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner A, Vollmann J, Kovac H, Crailsheim K. Oxygen consumption and body temperature of active and resting honeybees. J. Insect Physiol. 2003b;49:881–889. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1910(03)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakonigg G, Eveleigh L, Arnold G, Crailsheim K. Ontogeny of the cuticular hydrocarbon profiles of honeybee drones. J. Apic. Res. 2000;39:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Whiffler LA, Drusedau RM, Crewe RM, Hepburn HR. Defensive behaviour and the division of labour in the African honeybee (Apis mellifera scutellata) J. Comp. Physiol. A. 1988;163:401–411. [Google Scholar]