Abstract

Study objective

Advanced, pre-hospital procedures such as intravenous access are commonly performed by emergency medical services (EMS) personnel, yet little evidence supports their use among non-injured patients. We evaluated the association between pre-hospital, intravenous access and mortality among non-injured, non-arrest patients.

Methods

We analyzed a population-based cohort of adult (aged ≥18 years) non-injured, non-arrest patients transported by four advanced life support agencies to one of 16 hospitals from January 1, 2002 until December 31, 2006. We linked eligible EMS records to hospital administrative data, and used multivariable logistic regression to determine the risk-adjusted association between pre-hospital, intravenous access and hospital mortality. We also tested whether this association differed by patient acuity using a previously published, out-of-hospital triage score.

Results

Among 56,332 eligible patients, one half (N=28,978, 50%) received pre-hospital intravenous access from EMS personnel. Overall hospital mortality in patients who did and did not receive intravenous access was 3%. However, in multivariable analyses, the placement of pre-hospital, intravenous access was associated with an overall reduction in odds of hospital mortality (OR=0.68, 95%CI: 0.56, 0.81). The beneficial association of intravenous access appeared to depend on patient acuity (p=0.13 for interaction). For example, the OR of mortality associated with intravenous access was 1.38 (95%CI: 0.28, 7.0) among those with lowest acuity (score = 0). In contrast, the OR of mortality associated with intravenous access was 0.38 (95%CI: 0.17, 0.9) among patients with highest acuity (score ≥ 6).

Conclusions

In this population-based cohort, pre-hospital, intravenous access was associated with a reduction in hospital mortality among non-injured, non-arrest patients with the highest acuity.

Introduction

Background

Greater than one third of patients seen in emergency departments may be cared for by emergency medical services (EMS) personnel prior to hospital arrival.1, 2 In some circumstances, EMS personnel perform procedures to treat acutely ill patients, such as placement of intravenous access,3 endotracheal intubation,4 advanced cardiac life support,5 or fluid resuscitation.6 However, there is a lack of evidence supporting the efficacy of most of these pre-hospital interventions, especially among non-injured, non-arrest patients. As a consequence, the Institute of Medicine and National EMS Research Agenda have called for more rigorous evaluation of the association between advanced, pre-hospital procedures and patient outcomes.7, 8

Importance

Among the advanced procedures performed by emergency medical services personnel, placement of intravenous access is the most common.9 Typically placed in higher acuity patients, the proportion of non-injured patients in whom intravenous access is initiated may reach 60% in some EMS systems.10, 11 EMS personnel use pre-hospital intravenous catheters to deliver medications, administer intravenous fluid, or obtain samples of blood. Yet, over half of catheters may be unused by EMS personnel or deemed as over-treatment during post-hoc review.10, 11 Unnecessary initiation of pre-hospital intravenous catheters increases scene time,3 and may impact EMS system supply costs.9 More importantly, there is little evidence that indicates pre-hospital placement of intravenous access improves patient-centered outcomes for non-injured, non-arrest patients.

Goals of This Investigation

The objective of this analysis was to determine the association between pre-hospital intravenous access and hospital mortality in a population-based cohort of non-injured, non-arrest EMS patients. We hypothesized that placement of a pre-hospital intravenous catheter would be associated with a reduction in hospital mortality, particularly among patients at greatest risk for critical illness during hospitalization.

Methods

Study design, setting, and selection of patients

We analyzed patients who activated EMS during the 5-year period from 2002–2006 in King County, Washington, excluding metropolitan Seattle. We included patients transported by King County EMS to one of 16 facilities from a rural, suburban, and urban catchment of greater than 1.2 million persons.12) We linked EMS records to the Washington State Comprehensive Hospital Abstract Reporting System (CHARS) database from 2002–2007. CHARS is a statewide database of all hospitalizations, with detailed diagnostic, procedural, and discharge data. Pre-hospital and CHARS data were linked using a validated, probabilistic matching algorithm which is previously described.13 We excluded patients with cardiac arrest, traumatic injury, and pre-hospital intubation, as these conditions have near certain likelihood of requiring intravenous access by EMS providers. We excluded patients assessed by basic life support (BLS) only, as these providers do not place intravenous access in the EMS agencies under study. Among the remaining patients, we included EMS encounters which met the following criteria: 1) age ≥18 years, 2) documentation of out-of-hospital vital signs / physical exam, and 3) transport to a receiving facility. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards for the Washington State Department of Health, King County Emergency Medical Services, and the University of Washington.

EMS system

We studied a two-tier emergency medical system. The first response is staffed by emergency medical technician- fire fighters who are trained to provide basic life support. The second tier is staffed by paramedics who are trained to provide advanced cardiac life support. Paramedics are required to perform 35 intravenous catheter starts, annually, to remain eligible for certification. No protocol guides the insertion of intravenous access by paramedics, which was placed at the discretion of EMS personnel.

Primary exposure and outcome measures

We defined out-of-hospital intravenous access as the documentation of peripheral or central intravenous catheter placement by EMS providers. Catheter placement is documented by marking a checkbox under a procedure section of the EMS report. We excluded intraosseous catheters, as they are most commonly placed in pediatric patients during the study period.14–16 Data was unavailable on catheter starts which were unsuccessful or if paramedics administered intravenous medications. The primary outcome was hospital mortality, defined as a discharge disposition of “death” in CHARS. The accuracy of data reported in CHARS has been previously described.17

Variable definitions

We abstracted out-of-hospital, clinical data from the EMS database, including dispatch, demographic, procedures, and transport data. Diagnostic categories were determined by EMS personnel, including anaphylaxis/allergy, cardiovascular, respiratory, fall, neurologic, obstetric/gynecologic, metabolic/endocrine, alcohol-related, abdominal, psychiatric, medical-other, or unknown causes. Initial out-of-hospital vital signs, documented by first arriving EMS personnel, included respiratory rate (RR, breaths/min), heart rate (HR, beats/min), systolic blood pressure (SBP, mmHg), pulse oximetry (SaO2, %), and Glasgow Coma Scale score (GCS). We abstracted an index of illness severity as determined by EMS personnel: “life-threatening”, “urgent”, and “non-urgent”. We defined out-of-hospital location as home, nursing home, public building, street/highway, medical facility, or adult family home. We abstracted additional out-of-hospital procedures, including application of electrocardiogram monitoring, delivery of supplemental oxygen, bag-valve mask ventilation, or glucometry measurement. We defined mode of transport from scene to hospital as: advanced life support ambulance, basic life support ambulance, helicopter, private ambulance, or private automobile. We abstracted standard out-of-hospital time intervals (min),18 including call receipt to ALS unit notification, notification to ALS unit responding, unit responding to arrival at scene, total scene time, and scene to hospital arrival. Time-based covariates were log-transformed for analysis due to non-normality. The use and delivery of medications administered through intravenous catheters was not available in the database.

Missing data

Several of the collected variables were missing data. The frequency and distribution of missing data in this cohort is detailed elsewhere.13 To address missing data, we used a flexible multivariable imputation procedure of multiple chained regression equations, which generated values for all missing data using the observed data for all patients.19 This approach assumed that the missing data mechanism was random and conditional on observed covariates. We used 10 cycles of regression switching to create each of 11 independent datasets. We included all model covariates, our primary outcome, and one auxiliary variable (critical care utilization during hospitalization) in the imputation procedure. During the imputation, we maintained log-transformations for continuous, non-normally distributed variables without upper bounds (out-of-hospital time intervals). For continuous, non-normal variables with upper and lower bounds, we used predictive mean matching (e.g. GCS, SaO2).20 We modeled the EMS severity index using multinominal logistic regression.

Primary data analysis

We compared continuous data using means with standard deviation (SD) or medians with interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate for the distribution of each variable; proportions were compared using the χ2 test. We displayed the proportion of patients who received intravenous access over the range of initial systolic blood pressure (mmHg). To determine the association between out-of-hospital intravenous access and hospital mortality, we constructed a multivariable logistic regression model with robust (Huber-White) standard errors for regression coefficients. We included a priori-determined confounders guided by past literature and theory, including demographics (age, sex), out-of-hospital location, initial vital signs (HR, RR, SaO2, GCS, SBP), EMS diagnostic category, EMS severity index, mode of transport to receiving hospital, out-of-hospital time intervals, and additional EMS procedures (electrocardiographic monitoring, bag-valve mask ventilation). We included the calendar year of hospitalization and admitting hospital as fixed effects. All models were evaluated within independent imputed datasets, and estimates combined using Rubin's rules.21 To determine if the potential treatment effect of intravenous access varied by a patient's acuity of disease, we tested the significance of an interaction between intravenous access and an individual's risk of developing critical illness during the hospital stay. We used a previously published, internally validated, out-of-hospital risk score for critical illness to illustrate the variation of treatment effect across the spectrum of illness acuity.13 This risk score is populated by objective, categorized variables available to first-on-scene EMS personnel during out-of-hospital care, including age, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, Glasgow coma scale score, and pulse oximetry.

Sensitivity analyses

We assessed the robustness of the results in several sensitivity analyses. First, we used an alternate definition of our primary outcome (28-day mortality) to assess the internal validity of our findings. Second, we repeated the analysis accounting for the non-independence of patients cared for by the same paramedic using generalized estimating equations (GEE). Because paramedics respond in randomly assigned pairs in the EMS system, we grouped paramedics by the documenting provider. For this model, we restricted analysis to paramedics with at least 100 encounters during the study period (N=157 paramedics; N=49,049 encounters (88% of cohort)) and did not include receiving hospital as an adjustment variable (in order to obtain model convergence). Third, we determined the magnitude of a hypothetical, unmeasured confounder needed to account for the treatment effect using quantitative bias analysis.22 We varied the effect of this confounding variable on mortality and its' prevalence among non-catheterized patients, in order to determine how the association between intravenous access and mortality would change after adjustment. In these analyses, we assumed: 1) the prevalence of the unmeasured confounder among patients receiving pre-hospital intravenous access was 10%, 2) no modification of the effect of intravenous access by the unmeasured confounder, and 3) the confounder was uncorrelated with other variables in the model. All analyses were performed with STATA 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). All tests of significance used a two-sided p ≤0.05.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

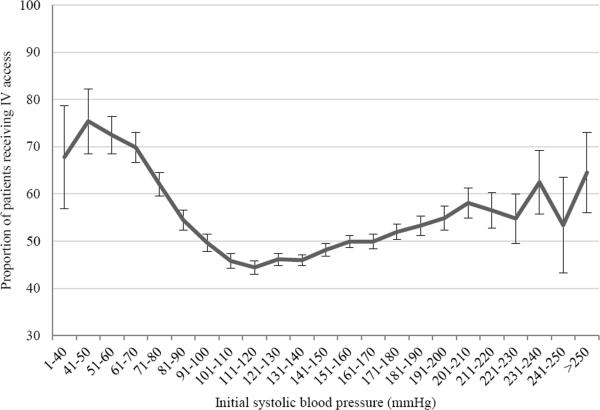

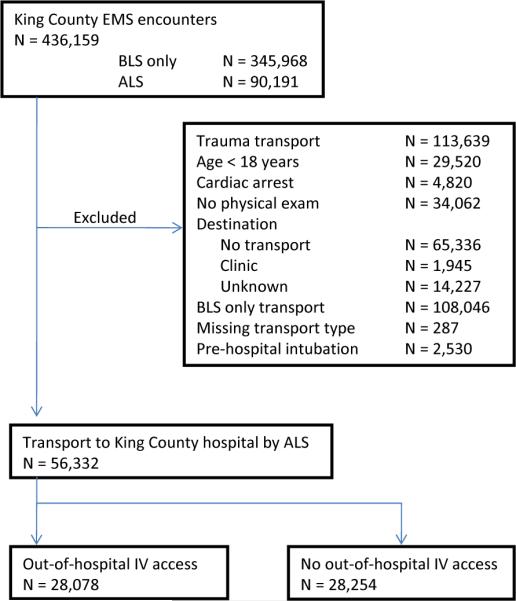

Among eligible patients who received advanced life support care and were transported to a receiving hospital (Figure 1), one half received out-of-hospital intravenous access (N=28,078, 50%). Hospital mortality was similar between groups (3% for both), though utilization of critical care services during hospitalization was more common among patients receiving intravenous access by EMS personnel (18 vs. 8%, Table 1). Patients receiving pre-hospital intravenous access were more commonly men, though were generally similar in age and initial out-of-hospital vital signs (Table 1). The proportion of patients receiving intravenous access varied broadly over the range of initial systolic blood pressure (Figure 2). The EMS personnel impression (cause of disease) differed between groups, with cardiovascular disease greater than twice as common among patients who received intravenous access (56 vs. 20%). Pre-hospital intravenous access was significantly more common among patients deemed to have life-threatening or urgent conditions by EMS personnel (Table 2), and was associated with a 6 minute increase, on average, in total EMS scene time. The majority of patients in whom intravenous access was initiated were transported to receiving hospitals by advanced life support personnel (93%).

Figure 1.

Subject accrual.

Abbreviations: EMS = emergency medical services; BLS = basic life support; ALS = advanced life support; IV = intravenous.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Covariate | No out-of-hospital IV access | Out-of-hospital IV access |

|---|---|---|

| N | 28,254 (50.1) | 28,078 (49.8) |

| Mean age in years, (SD) | 63 (20) | 65 (18) |

| Male gender, N (%) | 11,539 (42) | 13,147 (49) |

| Out-of-hospital location, N (%)^ | ||

| Routine / Home | 18,111(64) | 18,685 (67) |

| Public building | 1,736 (6) | 1,592 (6) |

| Street / highway | 770 (3) | 723 (2) |

| Adult family home | 1,101 (4) | 649 (2) |

| Medical facility | 1,395 (5) | 1,822 (6) |

| Nursing home | 3,010 (11) | 2,483 (9) |

| Initial out-of-hospital vital signs | ||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 140 ± 34 | 140 ± 40 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 90 ± 23 | 94 ± 31 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 20 [16–24] | 20 [16–24] |

| Glasgow com scale, (SD) | 14.2 (2.1) | 14.0 (2.5) |

| Oxygen saturation, % | 96 [89–98] | 96 [92–98] |

| EMS impression (cause of disease), N (%)^ | ||

| Cardiovascular | 5,757 (20) | 15,711 (56) |

| Respiratory | 5,136 (18) | 3,583 (13) |

| Neurological | 4,316 (15) | 2,151 (8) |

| Medical – other | 5,460 (19) | 1,379 (5) |

| Abdominal | 1,952 (7) | 946 (3) |

| Unknown | 1,736 (6) | 1,078 (4) |

| Alcohol / drug | 1,346 (5) | 1,174 (4) |

| Metabolic / endocrine | 831 (3) | 1,232 (4) |

| Psychiatric | 892 (3) | 121 (<1) |

| Anaphylaxis / allergy | 280 (1) | 350 (1) |

| Obstetric / gynecologic | 297 (1) | 248 (1) |

| Fall | 65 (<1) | 31 (<1) |

| Hospital outcomes, N (%) | ||

| Length of stay, days | 3 [2–5] | 3 [1–4] |

| Need for mechanical ventilation | 510 (2) | 824 (3) |

| Need for ICU admission* | 2,366 (8) | 4,952 (18) |

| In-hospital mortality | 732 (3) | 805 (3) |

| 28-day mortality | 1,207 (4) | 1,259 (4) |

Categories are mutually exclusive and do not include other locations or other diagnostic categories

Determined using critical care services revenue codes contained in CHARS (codes 200 –202, 207–213,

Figure 2.

Frequency of placement of intravenous access across initial systolic blood pressure (mmHg) during out-of-hospital care. Error bars represent 95% binomial confidence intervals (CIs).

Table 2.

Emergency medical services and incident characteristics

| Covariate | No out-of-hospital IV access | Out-of-hospital IV access |

|---|---|---|

| ALS response algorithm, N (%) | ||

| Initial dispatch | 15,654 (55) | 16,602 (59) |

| Upgraded by dispatch | 4,044 (14) | 3,652 (13) |

| Requested by BLS at scene | 7,223 (26) | 6,778 (24) |

| EMS severity code, N (%) | ||

| Life-threatening | 380 (1) | 2,381 (8) |

| Urgent | 8,715 (31) | 22,014 (78) |

| Non-urgent | 18,863 (67) | 3,639 (13) |

| Out-of-hospital response intervals, min | ||

| Call receipt to unit notification | 2.0 [1.0 – 6.2] | 1.6 [0.9 – 6.0] |

| Unit notification to responding | 1.6 [1.0 – 2.0] | 1.6 [1.0 – 2.0] |

| Responding to arrival at scene | 6.0 [4.0 – 8.0] | 6.0 [4.0 – 8.0] |

| Total time at scene | 19 [14 – 25] | 24 [20 – 30] |

| Scene to arrival at hospital | 13 [8 – 19] | 11 [7 – 16] |

| Interventions performed by EMS providers, N (%)* | ||

| ECG monitoring | 20,217 (72) | 26,112 (93) |

| Supplemental oxygen | 25,478 (90) | 27,491 (98) |

| Bag-valve mask ventilation | 194 (<1) | 544 (2) |

| Glucometry measurement | 2,043 (7) | 2,723 (10) |

| Mode of transport from scene, N (%) | ||

| Basic life support | 8,825 (31) | 701 (3) |

| Advanced life support | 3,744 (13) | 26,180 (93) |

| Helicopter | 47 (<1) | 89 (<1) |

| Private ambulance | 14,741 (52) | 1,010 (4) |

| Private automobile | 652 (2) | 16 (<1) |

| Critical illness score, N (%) | ||

| 0 | 2,813 (10) | 1,425 (5) |

| 1 | 14,007 (50) | 12,612 (45) |

| 2 | 7,334 (26) | 7,973 (28) |

| 3 | 2,918 (10) | 3,937 (14) |

| 4 | 908 (3) | 1,606 (6) |

| 5 | 214 (1) | 411 (1) |

| ≥6 | 60 (<1) | 114 (<1) |

Abbreviations: ALS=advanced life support; BLS=basic life support; ECG=electrocardiographic; EMS=emergency medical services

Main results

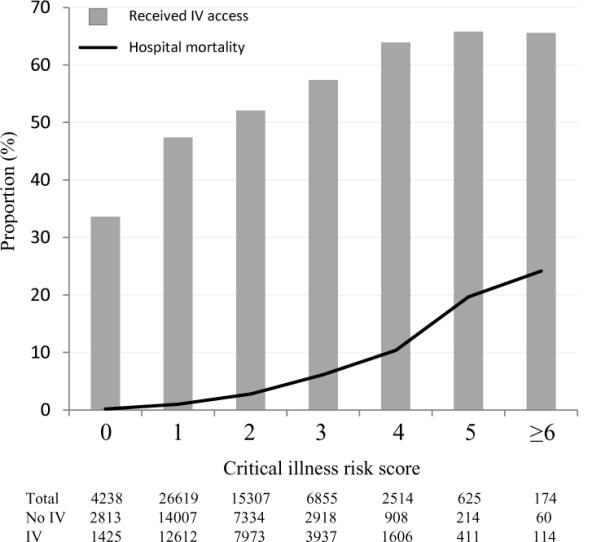

In unadjusted models, placement of pre-hospital intravenous access was associated with an 11% greater odds of hospital mortality (OR=1.11, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.23) (Table 3). However, after adjustment for illness severity, demographic, dispatch, and transport characteristics, pre-hospital intravenous access was associated with a lower odds of hospital mortality (OR=0.68, 95%CI: 0.56, 0.81). This reduction in odds corresponded to an absolute reduction in predicted mortality of 0.93% (95%CI: 0.5, 1.3%). In an a priori, risk-based sub-group analysis, we evaluated a previously published, out-of-hospital score for critical illness. We observed that the majority of patients were at low risk of critical illness (Figure 3), and that the prevalence of our primary exposure and outcome both increased over score values. When we included the risk score as an interaction term in the primary model (Wald test, χ2(df=6)= 8.6, p=0.13), we observed that the association between pre-hospital intravenous access and hospital mortality increased with score values from 0 to ≥6. For example, the OR of mortality associated with intravenous access was 1.38 (95%CI: 0.28, 7.0) among those with lowest acuity (score = 0). In contrast, the OR of mortality associated with intravenous access was 0.38 (95%CI: 0.17, 0.9) among patients with highest acuity (score ≥ 6).

Table 3.

Regression estimates of the association between out-of-hospital intravenous access and hospital mortality in unadjusted and adjusted models and sensitivity analyses.a

| Regression models | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | 1.11 | 1.0, 1.23 |

| Covariate-adjusted modelb | 0.67 | 0.56, 0.81 |

| Covariate-adjusted model with risk-based subgroupsc | ||

| 0 | 1.38 | 0.28,7.01 |

| 1 Low risk | 0.66 | 0.49, 0.89 |

| 2 | 0.8 | 0.63, 1.02 |

| 3 Intermediate risk | 0.68 | 0.53, 0.88 |

| 4 | 0.54 | 0.40, 0.74 |

| 5 High risk | 0.53 | 0.32, 0.85 |

| ≥6 | 0.39 | 0.17,0.9 |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||

| Covariate-adjusted model using 28-day mortality | 0.75 | 0.64, 0.86 |

| Generalized estimating equation modeld | 0.71 | 0.57,0.88 |

All estimates combined from 11 imputed datasets using Rubin's rules

Covariate-adjusted model includes age, gender, out-of-hospital location, initial pre-hospital vital signs, receiving hospital, year in cohort, mode of transport, EMS interventions, EMS diagnosis, and EMS severity code

Out-of-hospital risk score included as multiplicative interaction term with intravenous access and all variables in adjusted model. Risk categories (low, intermediate, high) as previously published.19

Cohort restricted to patients seen by paramedics with at least 100 encounters (N=49,049, 88% of total)

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients across critical illness scores who received intravenous access (grey bars and with hospital mortality (black line). Sample size (N) for each risk score, and by intravenous (IV) catheter status, is shown in table.

Sensitivity analyses

We defined our primary outcome as 28-day mortality, rather than hospital mortality, and observed no change in our results. Similarly, GEE models which account for correlation of data within paramedics did not change our results (Table 3). We used quantitative bias analysis to determine how unmeasured confounding (e.g. severity of illness) may bias our results (Table 4). We observed that a hypothetical confounder must be at least three times as prevalent among patients not receiving intravenous access (compared to those who did), and the odds of death among patients with the confounder to be twice as great as patients without the confounder for the adjusted risk of mortality of among patients who did and did not receive pre-hospital intravenous access to appear equivalent.

Table 4.

Quantitative bias analysis illustrating the attenuation in odds of hospital mortality comparing patients who do and do not receive out-of-hospital intravenous access under varying assumptions for a hypothetical, unmeasured confounder.a

| Odds ratio of hypothetical confounder | Prevalence of unmeasured confounder among patients not receiving pre-hospital intravenous access | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 1.5 | 0.68 (0.57, 0.82) | 0.70(0.58, 0.84) | 0.73 (0.61,0.89) | 0.77 (0.64, 0.92) |

| 2 | 0.7 (0.58, 0.84) | 0.73(0.61, 0.88) | 0.79 (0.66,0.95) | 0.85(0.71, 1.02) |

| 2.5 | 0.71 (0.59, 0.86) | 0.76(0.63, 0.91) | 0.85(0.70, 1.01) | 0.93(0.78, 1.11) |

| 3 | 0.72 (0.60, 0.87) | 0.78 (0.65, 0.94) | 0.89(0.74, 1.07) | 1.0(0.84, 1.20) |

| 3.5 | 0.74(0.61, 0.88) | 0.8 (0.67, 0.96) | 0.94(0.78, 1.12) | 1.07(0.89, 1.28) |

| 4 | 0.75 (0.62, 0.90) | 0.82 (0.68, 0.99) | 0.98(0.81, 1.17) | 1.13(0.95, 1.35) |

Shaded cells represent conditions in which our observed odds ratio would no longer be significant. Assumptions: 1) prevalence of unmeasured confounder among patients receiving pre-hospital intravenous access = 0.1, 2) no modification of the effect of intravenous access by the unmeasured confounder, 3) confounder uncorrelated with other variables in the model.

Limitations

The study has limitations. First, we were unable to determine how paramedics used intravenous catheters after placement. Without documentation of specific medications, fluid volume, or saline lock, we were unable to explore the specific mechanism(s) which may account for the observed treatment effect. Saline lock or non-use of pre-hospital intravenous access is variable across EMS systems (between 2 to 83%), and is modified by patient acuity.10, 11 We were unable to measure if paramedics were unsuccessful in placement of intravenous catheters, and if this was differential across severity of illness. Future studies of the association between intravenous catheters and patient outcome require improved data capture of procedure success and treatment delivered. Variables which populate the pre-hospital triage score were also missing in many patients. To address this limitation, we performed multiple imputation with predictive mean matching. This method is preferable to complete case analysis or single imputation because the mechanism underlying the missing data is unlikely to be completely random.23–25 We also cannot rule out that unmeasured confounding biased our regression models. Although we accounted for multiple measures of severity of illness, unmeasured paramedic, incident, or hospital characteristics may have biased the association between treatment and outcome. As such, we included each receiving hospital as a fixed effect in regression models. We also used quantitative bias analysis to estimate the effect of an unmeasured, hypothetical confounder on our findings.22 We found that this confounder must have a prevalence and association with mortality among controls which is unlikely. We acknowledge that unmeasured variation in EMS personnel characteristics, such as clinical acumen and procedural skill, may be present. Finally, the external validity of these results is also unknown, particularly among longer distance transport in rural settings, where pre-hospital intravenous access may be more common, or among EMS systems with rigorous protocols for catheter placement.26

Discussion

In this population-based cohort, we observed that placement of pre-hospital intravenous access among non-injured, non-arrest patients is associated with a lower odds of hospital mortality, after adjustment for demographic and incident characteristics, severity of illness, and receiving hospital. Importantly, the reduction in odds of mortality associated with pre-hospital intravenous access was greatest among the most severely ill patients. These results were robust to several sensitivity analyses which varied the definition of our primary outcome, the magnitude of an unmeasured, hypothetical confounder, and accounted for the non-independence of treatment decisions and clinical care provided by individual paramedics.

Multiple mechanisms may account for the association between pre-hospital intravenous access and reduction in the odds of hospital mortality. The placement of intravenous access by EMS personnel may facilitate the delivery of pharmacologic therapy or volume in both pre-hospital and hospital locations for life-threatening conditions such as arrhythmias, shock, and acute coronary syndromes. Also, pre-hospital intravenous access may enhance the hospital-based triage and treatment in emergency departments. For example, in a comparison cohort, vascular access and initiation of fluid resuscitation by EMS was associated with greater fluid administration and resolution of hemodynamic instability in severe sepsis patients within 6 hours of arrival at the emergency department.27 Alternatively, the association between intravenous access and patient outcomes may not represent a direct treatment effect, but rather exist as an “epiphenomenon” of better clinical judgment and care by individual EMS personnel. These results derive from a mature EMS system where all paramedics receive comparable training and have identical continuing education and clinical experience requirements for certification. Nonetheless, clinical acumen and experience of EMS personnel has been associated with improved outcomes in cardiac arrest resuscitation.28

The beneficial association of pre-hospital intravenous access with hospital survival was greatest among patients with the highest acuity, pre-hospital triage score.13 This finding suggests that timely pre-hospital interventions make a positive difference in the sickest patients, but may have little or no effect in less acute patients. Moreover, this risk-based, subgroup analysis underscores the importance of accounting for illness severity when studying advanced, pre-hospital procedures. In future prospective studies of advanced procedures, the results of the current study would suggest to use risk-based subgroups to uncover variation in EMS treatment effect across heterogeneous populations, and evaluate EMS systems with detailed data capture and record linking to patient outcomes.

One barrier to greater use of pre-hospital, intravenous access is the concern that delayed scene time will negatively impact patient outcomes.29–31 Conversely, trauma investigators report little association between out-of-hospital time and mortality.32, 33 We confirmed an increase in EMS scene time when comparing patients who did and did not receive intravenous access; yet, multivariable adjustment for these scene and transport time intervals did not abrogate the association between intravenous access and lower hospital mortality. Additional barriers to broader implementation of pre-hospital intravenous access include supply and equipment costs. Although individual catheters kits and intravenous line tubing may be low cost,11 greater study is required to determine if population-level changes in pre-hospital intravenous access protocols have untoward financial implications.

In this population-based outcomes study of non-injured, non-arrest patients transported by advanced life support, the placement of pre-hospital intravenous access was associated with a reduction in the odds of hospital mortality. When seeking to optimize EMS systems to improve outcomes, the findings support a strategy which favors early, targeted intravenous access particularly among those with evidence of most severe illness.

Acknowledgments

Funding Dr. Seymour is supported in part by a National Center for Research Resources grant from the National Institutes of Health (KL2 RR025015). Dr. Cooke is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. Dr. Rea is supported by a grant from the Washington Life Sciences Discovery Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ding R, McCarthy ML, Desmond JS, et al. Characterizing waiting room time, treatment time, and boarding time in the emergency department using quantile regression. Acad Emerg Med. Aug;17(8):813–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang HE, Weaver MD, Shapiro NI, et al. Opportunities for Emergency Medical Services care of sepsis. Resuscitation. Feb;81(2):193–197. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr BG, Brachet T, David G, et al. The time cost of prehospital intubation and intravenous access in trauma patients. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008 Jul–Sep;12(3):327–332. doi: 10.1080/10903120802096928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang HE, Balasubramani GK, Cook LJ, et al. Out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation experience and patient outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. Jun;55(6):527–537. e526. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stiell IG, Wells GA, Field B, et al. Advanced cardiac life support in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2004 Aug 12;351(7):647–656. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bickell WH, Wall MJ, Jr., Pepe PE, et al. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med. 1994 Oct 27;331(17):1105–1109. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410273311701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine . Emergency Medical Services at the Crossroads. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sayre MR, White LJ, Brown LH, et al. The National EMS Research Agenda executive summary. Emergency Medical Services. Ann Emerg Med. 2002 Dec;40(6):636–643. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.129241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minville V, Pianezza A, Asehnoune K, et al. Prehospital intravenous line placement assessment in the French emergency system: a prospective study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006 Jul;23(7):594–597. doi: 10.1017/S0265021506000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuzma K, Sporer KA, Michael GE, et al. When are prehospital intravenous catheters used for treatment? J Emerg Med. 2009 May;36(4):357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gausche M, Tadeo RE, Zane MC, et al. Out-of-hospital intravenous access: unnecessary procedures and excessive cost. Acad Emerg Med. 1998 Sep;5(9):878–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample. US Census Bureau-ACS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seymour CW, Kahn JM, Cooke CR, et al. Prediction of critical illness during out-of-hospital emergency care. JAMA. Aug 18;304(7):747–754. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerritse BM, Schalkwijk A, Pelzer BJ, et al. Advanced medical life support procedures in vitally compromised children by a helicopter emergency medical service. BMC Emerg Med. 10:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiorito BA, Mirza F, Doran TM, et al. Intraosseous access in the setting of pediatric critical care transport. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005 Jan;6(1):50–53. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149137.96577.A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowler R, Gallagher JV, Isaacs SM, et al. The role of intraosseous vascular access in the out-of-hospital environment (resource document to NAEMSP position statement) Prehosp Emerg Care. 2007 Jan–Mar;11(1):63–66. doi: 10.1080/10903120601021036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT., Jr. Validating administrative data in stroke research. Stroke. 2002 Oct;33(10):2465–2470. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000032240.28636.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr BG, Caplan JM, Pryor JP, et al. A meta-analysis of prehospital care times for trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006 Apr–Jun;10(2):198–206. doi: 10.1080/10903120500541324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Buuren S, Boshuizen HC, Knook DL. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Stat Med. 1999 Mar 30;18(6):681–694. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<681::aid-sim71>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall A, Altman DG, Royston P, et al. Comparison of techniques for handling missing covariate data within prognostic modelling studies: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. Jan 19;10(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley and sons; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lash TLFM, Fink AK. Applying quantitative bias analysis to epidemiologic data. Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ambler G, Omar RZ, Royston P. A comparison of imputation techniques for handling missing predictor values in a risk model with a binary outcome. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007 Jun;16(3):277–298. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall A, Altman DG, Royston P, et al. Comparison of techniques for handling missing covariate data within prognostic modelling studies: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 10:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Heijden GJ, Donders AR, Stijnen T, et al. Imputation of missing values is superior to complete case analysis and the missing-indicator method in multivariable diagnostic research: a clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006 Oct;59(10):1102–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez RP, Cummings G, Mulekar M, et al. Increased mortality in rural vehicular trauma: identifying contributing factors through data linkage. J Trauma. 2006 Aug;61(2):404–409. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000229816.16305.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seymour CW, Cooke CR, Mikkelsen ME, et al. Out-of-hospital fluid in severe sepsis: effect on early resuscitation in the emergency department. Prehosp Emerg Care. Apr 6;14(2):145–152. doi: 10.3109/10903120903524997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gold LS, Eisenberg MS. The effect of paramedic experience on survival from cardiac arrest. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2009 Jul–Sep;13(3):341–344. doi: 10.1080/10903120902935389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith JP, Bodai BI, Hill AS, et al. Prehospital stabilization of critically injured patients: a failed concept. J Trauma. 1985 Jan;25(1):65–70. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198501000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sampalis JS, Lavoie A, Williams JI, et al. Impact of on-site care, prehospital time, and level of in-hospital care on survival in severely injured patients. J Trauma. 1993 Feb;34(2):252–261. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199302000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seamon MJ, Fisher CA, Gaughan J, et al. Prehospital procedures before emergency department thoracotomy: “scoop and run“ saves lives. J Trauma. 2007 Jul;63(1):113–120. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31806842a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lerner EB, Billittier AJ, Dorn JM, et al. Is total out-of-hospital time a significant predictor of trauma patient mortality? Acad Emerg Med. 2003 Sep;10(9):949–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newgard CD, Schmicker RH, Hedges JR, et al. Emergency medical services intervals and survival in trauma: assessment of the “golden hour“ in a North American prospective cohort. Ann Emerg Med. Mar;55(3):235–246. e234. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]