Abstract

β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilins mutations cause early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD). Some FAD-based mouse models produce amyloid plaques, others don’t. β-Amyloid (Aβ) deposition can manifest as compact and diffuse plaques; it is unclear why the same Aβ molecules aggregate in different patterns. Is there a basic cellular process governing Aβ plaque pathogenesis? We showed in some FAD mouse models that compact plaque formation is associated with a progressive axonal pathology inherent with increased expression of β-secretase (BACE1), the enzyme initiating the amyloidogenic processing of APP. A monoclonal Aβ antibody, 3D6, visualized distinct axon terminal labeling before plaque onset. The present study was set to understand BACE1 and axonal changes relative to diffuse plaque development and to further characterize the novel axonal Aβ antibody immunoreactivity (IR), using triple transgenic AD (3xTg-AD) mice as experimental model. Diffuse-like plaques existed in the forebrain in aged transgenics and were regionally associated with increased BACE1 labeled swollen/sprouting axon terminals. Increased BACE1/3D6 IR at axon terminals occurred in young animals before plaque onset. These axonal elements were also co-labeled by other antibodies targeting the N-terminal and mid-region of Aβ domain and the C-terminal of APP, but not co-labeled by antibodies against the Aβ C-terminal and APP N-terminal. The results suggest that amyloidogenic axonal pathology precedes diffuse plaque formation in the 3xTg-AD mice, and that the early-onset axonal Aβ antibody IR in transgenic models of AD might relate to a cross-reactivity of putative APP β-carboxyl terminal fragments.

Keywords: Amyloid plaque, axonal pathology, synaptoplasticity, aging, dementia

Introduction

Extracellular β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques are one of the pathological characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and appear to be closely linked to synaptic and neuritic deficits in this disease [Fiala, 2007; Castellani et al., 2010]. However, the mechanism underlying amyloid accumulation/deposition and the causal relationship of this pathology to synaptic/neuritic lesions are still not fully understood [Herrup, 2010; Pimplikar et al., 2010; Struble et al., 2010]. One important question regarding plaque pathogenesis concerns the origin of extracellular Aβ products. Biochemical genesis of Aβ involves sequential enzymatic cleavages of β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β-secretase-1 (BACE1), and then by γ-secretase complex with presenilins (PS1 and PS2) serving the essential catalytic components. APP, BACE1 and PSs appear to be largely expressed in neurons [Elder et al., 1996; Lee et al., 1996; Kim et al., 1997; Bigl et al., 2000; Cai et al., 2001; Irizarry et al., 2001; Yan et al., 2004]. Accordingly, neurons may be the primary anatomical source of brain Aβ.

However, it remains unclear as to which neuronal compartment, soma, dendrites or axon, serves the major source of extracellular Aβ in the plaques. Some Aβ antibodies may label neuronal somata and primary dendrites, although recent studies have raised concern as to whether this labeling reflects a presence of Aβ per se or other APP cleavage products [Wegiel et al., 2007; Aho et al., 2011; Gouras et al., 2010]. Notably, plaques can develop in the white matter that has few neuronal somata [Fiala, 2007; Cai et al., 2010]. Therefore, it appears that neither neuronal somata, nor dendritic, Aβ release represents an essential precondition for plaque formation. On the other hand, if Aβ deposits originate from the axonal compartment, plaque occurrences in both grey and white matter might be reconciled. Evidence supporting an axonal source of Aβ deposits includes that deafferentation leads to reduced plaque formation in corresponding axonal terminal fields [Lazarov et al., 2002; Sheng et al., 2002; van Groen et al., 2003; Robertson et al., 2009].

An enzyme-product pair retains an intrinsic measure for biochemical causal relationship. Per this concept, we recently carried out correlative BACE1 and Aβ analysis in several transgenic models of AD (2XFAD, 5XFAD and Tg2576), demonstrating that the onset and evolution of typical neuritic plaques relate to a progressive amyloidogenic axonal pathology [Zhang et al., 2009; 2010; Cai et al., 2010]. This axonal pathology occurs initially at perisomatic axon terminals and axonal processes as distinctly labeled by the monoclonal antibody 3D6 raised against the N-terminal amino acid residues of the Aβ domain [Zhang et al., 2009]. However, because the Aβ sequence is also a part of the APP β-C-terminal fragments (APP β-CTF), it remains uncertain whether this axonal 3D6 immunoreactivity (IR) actually reflects a presence of Aβ or β-CTF.

The triple transgenic mouse model of AD (3xTg-AD) carries mutant human APP (APPSwe), PS1 (PS1M146V) and tau (TauP301L), and develop amyloid plaques, tauopathy, and learning and memory deficits with age [Oddo et al., 2003]. Amyloid plaques in the forebrain develop fairly late and appear to be largely diffuse-like in these mice [Mastrangelo and Bowers, 2008]. Therefore, we studied amyloid plaque morphology and development relative to BACE1 and neuritic alterations in this mouse model. We also pursued a cross-examination using different Aβ and APP antibodies to explore the nature or implication of the early-onset Aβ antibody labeling at axon terminals first noted in other transgenic models of AD [Zhang et al., 2009].

Materials and Methods

Animals

A colony of 3xTg-AD and non-transgenic (non-Tg) mice was established in-house from breeding pairs provided by Dr. Frank LaFerla at University of California Irvine [Oddo et al., 2003]. Considered the gender difference in amyloid pathology in these transgenics [Hirata-Fukae et al., 2008], the present study used males to minimize the complexity in data interpretation. Brains from 3xTg-AD mice aged at 1–2 (n=6), 4–6 (n=8), 12–14 (n=8), 18–22 (n=10) and 24–26 (n=6) months were examined anatomically and biochemically. Brains from age-matched non-transgenics (n=4/age, hemi-brain for anatomy and hemi-brain for biochemistry) were batch-processed with the transgenic counterparts. Animal use was in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All procedures in the present study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Southern Illinois University.

Tissue preparation

For anatomical studies, animals were transcardially perfused under overdose anesthesia (sodium pentobarbital 100 mg/kg, i.p.) with 0.01M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4, PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were dissected out and postfixed overnight, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose at 4 °C until sank, and sectioned using a cryostat (Microm HM525, Germany). Fixed cerebral hemispheres were prepared into coronal or sagittal sections. Fiducial markers (small corner cutting and needle punch) were made at various cortical locations, which were used during microscopic examination to identify sections from individual brains among batch-processed sections from different animals. A total of 12 sets of 30 µm-thick sections across the entire brain were collected consecutively in PBS in cell culture plates. In addition, six sets of 12 µm (collected in PBS) and 12 sets of 6 µm (thaw-mounted) coronal sections were collected from the septum to hippocampus levels, to visualize IR at fine neuronal terminals. The sections were stored at −70 and −20 °C before histological staining (kept in a cryoprotectant or frozen).

For biochemical studies, brains were briefly perfused with cold PBS to remove blood, and the cerebral cortex of one hemisphere was separated and snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen. Cortical samples from all age groups were stored at −70 °C before homogenization. The other hemisphere was fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS before cryoprotection with 30% sucrose, and also used for histological studies.

Immunohistochemistry

For the avidin-biotin-based immunohistochemistry, sections were treated with 1% H2O2 in PBS for 30 minutes, and pre-incubated in 5% normal horse serum with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 hour. For BACE1 labeling, sections were else pretreated in 50% formamide and 50% 2XSSC (0.15 M sodium chloride and 0.015 M sodium citrate) at 65 °C for 30–60 minutes (for 6, 12 and 30 µm sections) [Zhang et al., 2009]. For Aβ antibody labeling, sections were first treated with 50% formic acid at room temperature for 10–30 minutes depending on section thickness. In experiments specifically designed to compare the cellular and extracellular labeling patterns between different Aβ antibodies, sections were subjected to a stronger formic acid digestion (90% for 10–30 minutes), or without formic treatment. Sections were thoroughly washed with PBS following these pretreatments, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies at pre-optimized concentrations in PBS containing appropriate blocking sera (see Table 1 for antibody sources and dilutions). The sections were further reacted with a biotinylated pan-specific secondary antibody (horse anti-mouse, rabbit and goat IgG) at 1:400 for 1 hour, and subsequently in freshly prepared avidin-biotin complex (ABC) solution (1:400) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for an additional hour. Immunoreactivity was developed using 0.003% H2O2 and 0.05% diaminobenzidine (DAB) with or without 0.025% NiCl and 0.025% CoCl enhancement. Three 10 minute PBS washes were used between incubations.

Table 1.

Primary antibodies used in the present study

| Antibody | Source | Product # | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| mouse anti-Aβ1–5, 3D6 | Elan | Lot#1132 | (1:3000) |

| mouse anti-Aβ1–16, 6E10 | Signet | 39320 | (1:4000) |

| mouse anti-Aβ17–24, 4G8 | Signet | 39240 | (1:4000) |

| rabbit anti-Aβ17–31 | H. Akiyama | E50 | (1:2000) |

| rabbit anti-Aβ36–40 | H. Mori | Ter40 | (1:2000) |

| rabbit anti-Aβ38–42 | H. Mori | Ter42 | (1:2000) |

| mouse anti-amyloid precursor protein, 22C11 | Millipore | MAB348 | (1:2000) |

| rabbit anti-amyloid precursor protein, C-terminal | Serotec | AHP538 | (1:1000) |

| rabbit anti-amyloid precursor protein, C-terminal | E.H. Koo | CT15 | (1:2000) |

| rabbit anti-amyloid precursor protein, C-terminal | Sigma-Aldrich | A8717 | (1:1000) |

| rabbit anti-BACE1 (a.a. 46–163) | H. Cai | anti-BACE1α | (1:2000) |

| goat anti-choline acetyltransferase | Millipore | AB1447 | (1:1000) |

| rabbit anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) 67 | Millipore | AB1511 | (1:2000) |

| mouse anti-GAD67 | Millipore | MAB5406 | (1:4000) |

| mouse anti-γ-aminobutyric acid transporter-1 | Millipore | MAB5406 | (1:4000) |

| mouse anti-growth-associated protein | Sigma-Aldrich | G9264 | (1:4000) |

| mouse anti-microtubule associated protein-2 | Sigma-Aldrich | M9942 | (1:2000) |

| rabbit anti-phosphorylated-tau (p-Ser199/Ser202) | Sigma-Aldrich | T6819 | (1:3000) |

| mouse anti-phosphorylated-tau (p-Ser396/Ser404) | P. Davies | PHF1 | (1:4000) |

| mouse anti-parvalbumin | Sigma-Aldrich | P3088 | (1:4000) |

| mouse anti-synaptophysin | Millipore | MAB329 | (1:4000) |

| rabbit and-synaptophysin | Epitomics | 1485-1 | (1:1000) |

| mouse anti-β-actin | GenScript | A00702 | (1:8000) |

| mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylase | Sigma-Aldrich | T2928 | (1:4000) |

| mouse anti-vesicular glutamate transporter-1 | Millipore | MAB5502 | (1:2000) |

For double immunofluorescence, sections were incubated in PBS containing 5% donkey serum and a pair of primary antibodies from different animal species (Table 1), followed by a 2 hour reaction with a pair of Alexa Fluor® 488 and Alexa Fluor® 594 conjugated secondary antibodies raised in donkey against the IgGs of two different species (mouse, rabbit or goat) (1:200, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The sections were then counter-stained with bisbenzimide (Hoechst 33342, 1:50000), washed 3 times in PBS and mounted with anti-fading medium. Initial antibody specificity tests entailed preabsorption of primary antibody with neutralizing peptide or omission of primary antibody in the incubation buffer. These controls yielded no specific labeling. The specificity of anti-BACE1α has been verified previously for both western and immunohistochemical applications [Laird et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2009].

Western blot

Cerebral hemispheres including the cortex and hippocampus were homogenized by sonication in T-PER buffer (10x w/v) (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and centrifuged at 15,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 minutes. The supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations determined by DC protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Extract containing 25 µg protein was run on each lane in 12% SDS-PAGE gels (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, CA, USA). The polypeptides were electrotransferred to Trans-Blot® pure nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Nitrocellulose membranes were immunoblotted for BACE1, APP C-terminal fragments and β-actin. Bound proteins were visualized with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:20000, Bio-Rad Laboratories) and the ECL Plus™ Western Blotting Detection kit (GE Healthcare Life Sci., Piscataway, NJ, USA). Immunoblot images were documented in a UVP Biodoc-it™ system (UVP, Inc, Upland, CA, USA).

APP β-site cleavage activity assay

β-site APP cleavage enzymatic activity in the above-mentioned cerebral homogenates was measured in 96-well transparent flat-bottom plates using a commercial kit (#565785, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) following manufacturer’s instruction. Equal quantities (50 µg) of proteins were loaded in each well in duplicates, and signal was captured in a Bio-Rad microplate reader.

Imaging, data analysis and statistic testing

Sections were examined on an Olympus (BX60) fluorescent microscope equipped with a digital camera and image analysis system (Optronics, Goleta, CA, USA). A Zeiss fluorescent microscope (Axio Imager, equipped with Apo Tom analysis system, Germany) was also used to study IR at fine neuronal terminals in the 6 µm-thick sections. Images (1600×1200 pixels) were taken using 4X to 40X objective lens (with an ocular lens at 10X). Optic density in area of interest was measured with the OptiQuant analysis software (Parkard Instruments, Meriden, CT, USA). Data were processed with Excel, and statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests (Prism GraphPad 4.1, San Diego, CA, USA). The minimal significance level was set at p<0.05. Figure panels were assembled using Photoshop 7.1.

Results

Sections from non-Tg mouse brains were processed in parallel with 3xTg-AD tissue to evaluate antibody specificity and altered labeling pattern in the transgenics. In general, no specific labeling for Aβ or phosphorylated tau (p-tau) was found in any non-Tg brain. BACE1 IR in non-Tg forebrain was restricted to neuropil, with a characteristic strong labeling at the hippocampal mossy fiber terminals and in the olfactory bulb glomeruli [Zhang et al., 2009, 2010]. Consecutive sets of 30 µm-thick sections from each transgenic brain were immunostained with BACE1, Aβ and p-tau antibodies with the peroxidase-DAB method, to confirm the transgenic phenotype and to evaluate overall immunolabeling pattern and cellular localization. Double immunofluorescence was applied on 12 µm-thick and 6 µm-thick sections to examine colocalization around plaques and at fine terminal profiles, respectively. The overall age-related evolution of Aβ antibody IR was assessed systematically using 3D6 and 6E10, which detected extracellular Aβ deposition similarly, but displayed fairly distinct difference regarding labeling in neuronal somata [Zhang et al., 2009].

Compact and diffuse-like amyloid plaques in aged 3xTg-AD mice

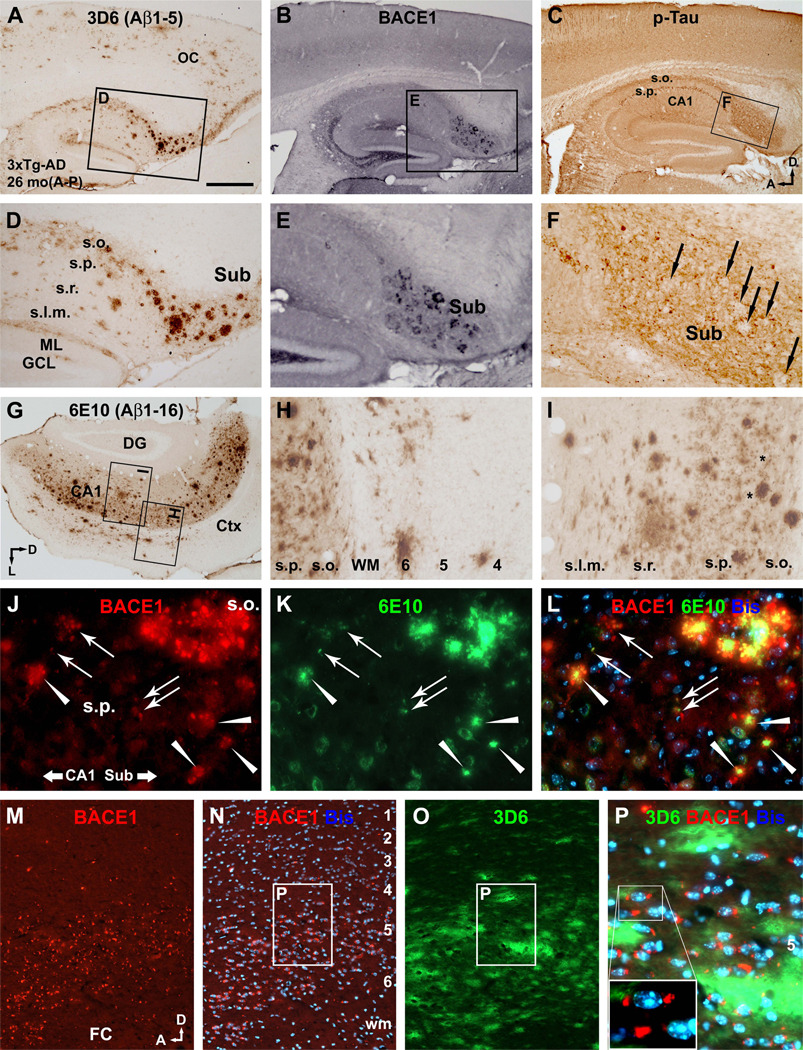

In 24–26 month-old transgenics, compact-like plaques exhibited strong 3D6 and 6E10 IR, had relatively distinct border, and were present most impressively in the subiculum (Fig. 1A, D, G). In adjacent sections, BACE1-labeled dystrophic neurites were present in the same area, and organized as rosette-like structures (Fig. 1B, E). An unlabeled center was visible among some large neuritic clusters (Fig. 1E). In double immunofluorescence, BACE1 and 3D6/6E10 IR colocalized around small and large compact plaques, with the strongest Aβ IR occurred at the center surrounded by BACE1-labeled dystrophic neurites (Fig. 1J–L). These compact-like plaques resembled the so-called primitive and cored neuritic plaques [Fiala, 2007; Zhang et al., 2009].

Fig. 1.

Overall pattern of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaque pathology and phosphorylated-tau (p-tau) expression in the cerebral cortex and hippocampal formation in an aged (26 month-old) 3xTg-AD mouse. Panel (A) shows 3D6 labeling of a large amount of extracellular Aβ deposition in the cortex and hippocampus in a sagittal section, appearing largely as diffuse-like plaques. The framed area is enlarged as panel (D) illustrating a group of heavily labeled compact-like plaques in the subiculum. Panel (B) shows the pattern of BACE1 labeling in an adjacent section, with distinctly labeled dystrophic neurites also occurred in the subiculum (E). Panel (C) depicts fairly abundant p-tau immunoreactivity in the cortex and hippocampal formation. Labeling in CA1 pyramidal neuronal somata is visible at low magnification, as is a band of labeling along the stratum oriens extending into the subiculum. Areas with reduced p-tau labeling exist in the subiculum (F). Panels (G–I) show 6E10 labeling in a coronal section passing the occipital lobe. Numerous amyloid plaques are seen in the subiculum, hippocampus and the deep cortex (G). The plaques are mostly ill-bordered and appears spreading in the periphery (H, I). The perikarya of hippocampal pyramidal neurons appear to be weakly labeled (I). Panels (J–L) show colocalization of BACE1 and 6E10 immunofluorescent labeling around small (arrows) and larger (arrowhead) primitive neuritic plaques, and around a very large multi-cored neuritic plaque (upper-right corner). Panels (M–P) show the presence of numerous BACE1 labeled terminal-like elements around 3D6 labeled diffuse plaques in the cortex. The BACE1 labeled profiles are generally small, but vary in size and shape, and often appose to cortical cells (P). OC: occipital cortex; FC: frontal cortex; Sub: subiculum; WM: white matter; GCL: granule cell layer; ML: molecular layer; s.o.: stratum oriens; s.p.: stratum pyramidale; s.r.: stratum radiatum; s.l.m.: stratum lacunosum-moleculare. Cortical layers are denoted with Arab numbers. Scale bar in (A) = 500 µm in (A) applying to (B, C, G); equivalent to 250 µm for (D–F, H, I, M–O); and 100 µm for (J–L, P).

3D6 and 6E10 also visualized a large amount of extracellular Aβ deposition appearing as diffuse-like plaques across the cortex and hippocampal formation (Fig. 1A, D, G). These plaques varied in sizes, but were ill-bordered and expressed relatively light Aβ IR (Fig. 1H, I). In adjacent sections, BACE1-labeled neuritic clusters were not detectable around the diffuse plaques (Fig. 1A, B, D and E). However, BACE1 immunofluorescence exhibited a differential pattern in thinner (6 and 12 µm) sections, with fairly distinct BACE1 IR occurred as fine elements in areas with diffuse Aβ deposition (Fig. 1M–O), which occurred apposing to but also away from perikarya (Fig. 1P).

The somata of some pyramidal neurons were labeled by 6E10 in DAB and immunofluorescent preparations in the aged transgenics (Fig. 1H, I, K). p-Tau IR was fairly abundant in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, localized to the somata and dendrites of some pyramidal neurons (Fig. 1C). A band of p-tau IR occurred across the stratum oriens (s.o.) (Fig. 1C). p-Tau IR appeared to be reduced around compact plaques in the subiculum (Fig. 1F).

Pre-plaque BACE1/Aβ antibody labeling and plaque onset in 3xTg-AD mice

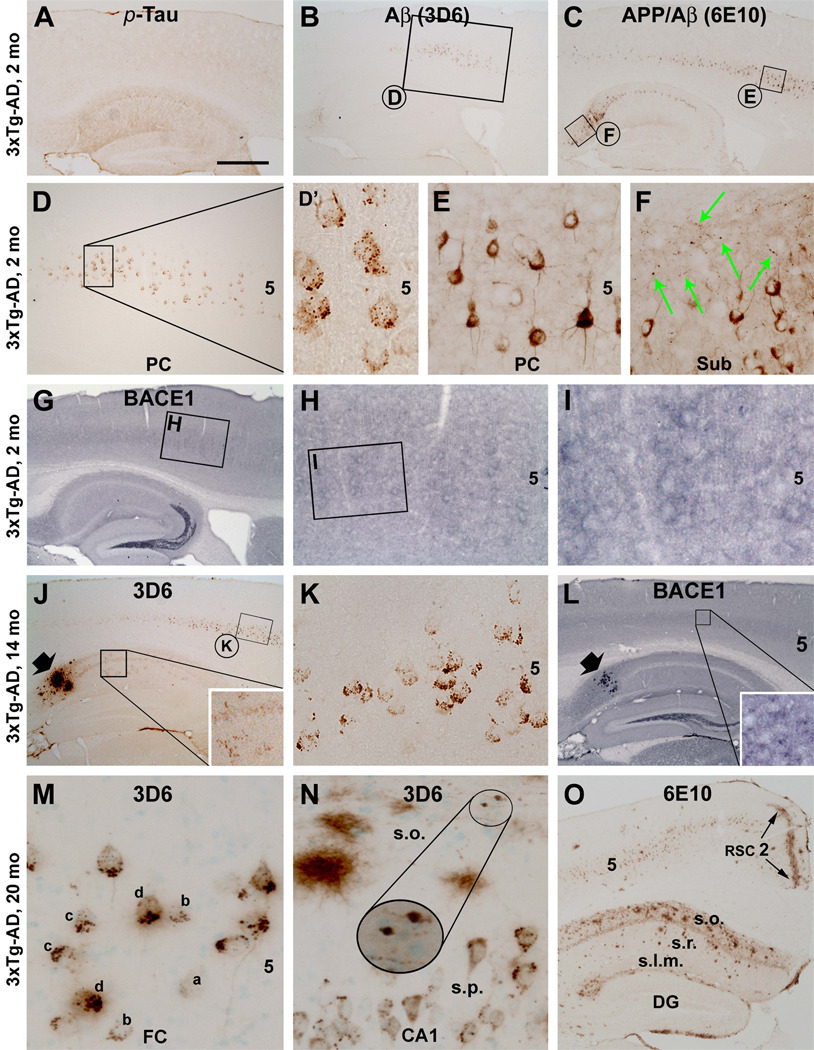

p-Tau, 3D6 and 6E10 labelings were readily detectable in 1–2 month-old transgenics in the cerebral cortex and hippocampal formation, with 3D6 and 6E10 IR occurred over layer V and the pyramidal cell layer of the subiculum and CA1 (Fig. 2A–C). At high magnifications, 3D6 IR in cortical layer V and subiculum appeared as small but distinct punctuate or granular structures predominantly around the pyramidal neuronal somata (Fig. 2D, D’). In contrast, 6E10 visualized the somata as well as proximal dendrites and axon of the pyramidal neurons (Fig. 2E). It should be noted that 6E10 also visualized some slightly swollen axon terminals in the subiculum (Fig. 2F, green arrows). BACE1 IR in the cortex and hippocampus was neuropil-like (Fig. 2G), and appeared to be slightly increased around some large layer V perikarya (Fig. 2H, I). During the following months, the overall laminar pattern of BACE1, 3D6, 6E10 and p-tau immunolabeling in the forebrain remained largely comparable to that seen at 2 month. However, age-related increases in BACE1 and Aβ antibody IR at neuronal terminals were detectable in both the cortex and white matter (see double immunofluorescent results).

Fig. 2.

Development of Aβ and BACE1 antibody labeling in the cerebral cortex and hippocampal formation in 3xTg-AD mice, assessed at various ages as indicated. Panels (A–C) show p-tau, 3D6 and 6E10 labelings readily detectable in a 2 month-old animal. p-Tau labeling is higher in the hippocampal CA1 relative to other regions (A). 3D6 and 6E10 labeling occurs across cortical layer V and the pyramidal cell layer of the subiculum and CA1 (B, C). At high magnification, 3D6 labeling appears largely as perisomatic puncta or granules (D, D’), whereas 6E10 labeling is intracellular (E, F). However, some neuronal processes (green arrows) with local swelling are labeled by 6E10 in the subiculum (F). BACE1 labeling at this age appears as neuropil reactivity in the cortex and most hippocampal layer except for a heavy labeling at the mossy fiber terminals (G). Labeling appears to be somewhat increased around some large layer V cell bodies (H, I). Panels (J–L) illustrate 3D6 and BACE1 labeling in a 14 month-old transgenics. A small group of compact-like plaques (J, L, fat arrow) occurs in the subiculum, concurrently expressing heavy 3D6 and BACE1 reactivity. 3D6 labeled puncta or granules clearly occur around layer V pyramidal neurons, but their amount and labeling intensity vary from one cell to another (K). Punctuate labeling also exists in the hippocampus (enlarged insert in J). Small dot-like BACE1 labeling is visible in the cortex at high magnification (enlarged insert in L). Panels (M, N) show a trend of increase and aggregation (a→b→c→d) of 3D6 labeled granules around layer V pyramidal neurons in a 20 month-old transgenics. These granules are also seen around CA1 pyramidal neuronal somata, but are less numerous relative to the cortex (N). Diffuse-like amyloid plaques in varying size as well as axonal processes with local swelling are present around the stratum oriens (s.o.) (N). Panel (O) shows an overview of amyloid plaques in the cortex and hippocampal formation in this 20 month-old animal, as revealed by 6E10. A small amount of plaques occurs in the cortex, except for a clear band of diffuse Aβ labeling along layer II of the retrosplenial cortex (RSC). Many diffuse-like plaques are present in the hippocampus, especially in the s.o. (O). Abbreviations are the same as defined in Fig. 1. Scale bar = 500 µm in (A) applying to (B, C, G, J, L); equivalent to 350 µm for (O); 250 µm for (D, H); 100 µm for (E, F, K) and 50 µm for (D’, M, N).

The onset of compact-like plaques in the forebrain occurred around 12 month of age in our colony of the 3xTg-AD mice, emerged first in the subiculum as a few small isolated profiles coexpressing BACE1 and extracellular 3D6/6E10 IR (not shown). By 14 month, several densely-labeled plaques were present in the subiculum accompanied by small satellite plaques (Fig. 2J). BACE1-labeled dystrophic neurites matched site-specifically with these subicular plaques (Fig. 2L). Punctuate or terminal-like 3D6 labeling was fairly prominent at this stage, with a trend of aggregation around principal neurons (Fig. 2K).

In 20 month-old transgenics a small amount of diffuse-like plaques emerged in the cortex, mostly in layers V, VI and the white matter, but a band of diffuse Aβ labeling occurred in layer II of the retrosplenial cortex (Fig. 2N, O) [also see Robertson et al., 2009]. Many diffuse-like plaques existed in the hippocampal formation, mostly over the s.o. (Fig. 2O). It should be noted that large diffuse-like plaques might exhibit fairly strong Aβ IR around the center, although they had an apparently spreading periphery (Fig. 2N). 3D6-labeled perisomatic granular profiles were apparently aggregated around many layer V and some hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Fig. 2M, N). Also, 3D6, 6E10 and BACE1 labeled swollen axonal processes were seen in the cortex and hippocampus, mostly distinct in the white matter (Fig. 2N; Suppl-Fig. 1A–D). Extracellular Aβ deposits were present around some of these swollen processes (Fig. 32N; also see S-Fig. 2A, D).

Localization of BACE1/Aβ antibody labeling to axonal structures in 3xTg-AD mice

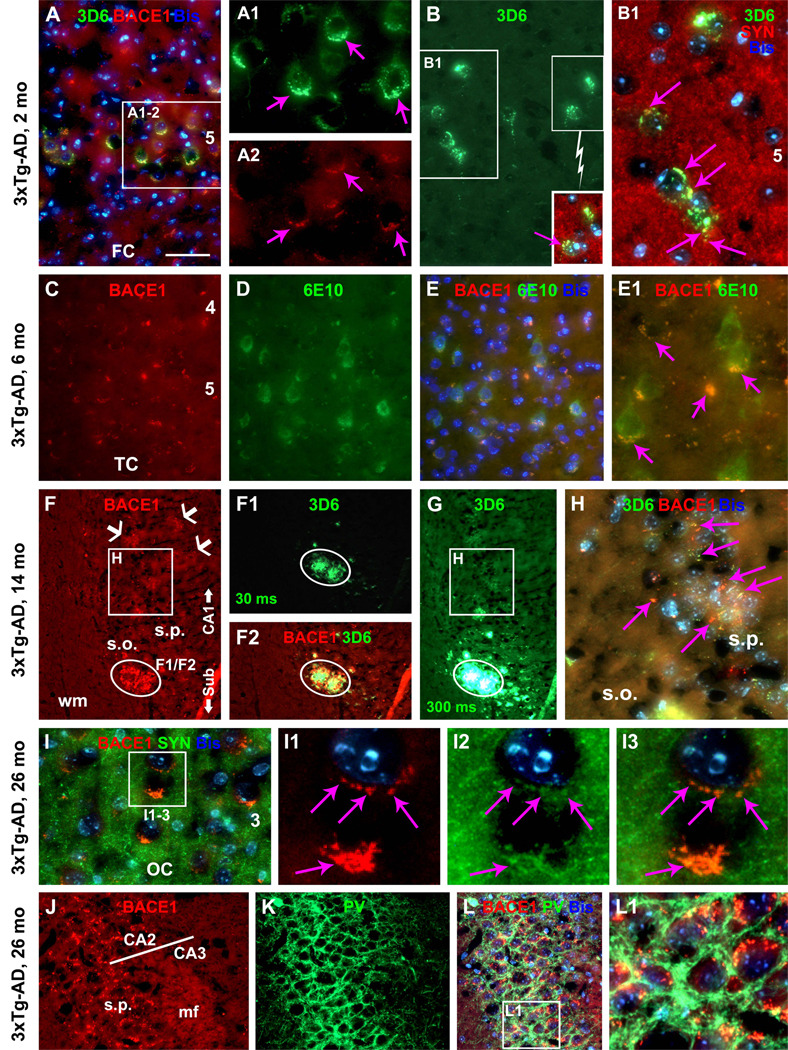

Multiple pairs of double immunofluorescence were used to characterize the terminal or neuritic labeling of BACE1, 3D6 and 6E10 in the 3xTg-AD mice before and after plaque onset. Overall, the labeling was found to colocalize with axonal but not dendritic markers, as with other transgenic models [Zhang et al., 2009, 2010]. For example, BACE1-labeled dystrophic neurites colocalized with synaptophysin (S-Fig. 1E–G), growth associated protein 43 (GAP-43) (S-Fig. 1H–J) and APP (S-Fig. 1K–M), but not with MAP-2 (data not shown). In hippocampal s.o., 3D6 labeled processes co-localized partially with neurogranin (S-Fig. 2A–C), a protein expressed in excitatory pyramidal neurons [Xiong et al., 2008]. We also verified BACE1 colocalization with 3D6 or 6E10 IR at perisomatic puncta around cortical (Fig. 3A–A2, C–E1) and hippocampal (Fig. 3F–H) neurons before and after plaque onset. These same perisomatic profiles colocalized with synaptophysin (Fig. 3B, B1, I–I3). Moreover, BACE1 or 3D6 IR could colocalize with a number of interneuron markers around cortical and hippocampal pyramidal somata, for example, parvalbumin (Fig. 3J–L1) and GABA transporter-1 (S-Fig. 2D–F). In contrast to the transgenics, the BACE1 and Aβ antibodies did not visualize dystrophic neurites or perisomatic granular/punctuate structures in non-Tg animals (S-Fig. 1N–Q).

Fig. 3.

Early occurrence and localization of BACE1 and Aβ antibody labeling of axon terminals and axonal processes in 3xTg-AD mouse cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Panels (A–A2) show colocalization of BACE1 and 3D6 labeling at perisomatic sites (pointed by purple arrows) around a subset of layer V pyramidal neurons in a 2 month-old animal. Panels (B and B1) and insert show colocalization of 3D6 and synaptophysin (SYN) labeling at the perisomatic sites. Panels (C–E1) show similar colocalization of BACE1 and 6E10 labeling at fine terminal elements apposing to and away from layer V pyramidal neuronal somata with intracellular 6E10 reactivity in a 6 month-old mouse. Panels (F–H) illustrate colocalization of BACE1 and 3D6 labeling in a compact-like plaque (cycled, F–G) as well as axonal processes around the stratum pyramidale (H). Two exposure times (30 ms in F1 and 300 ms in G) were used to capture the 3D6 immunofluorescent signal, with the longer exposure caused a bleach effect because of the very bright 3D6 signal (G). Panels (I–I3) show that in the 26 month-old animal BACE1 and SYN colocalize at perisomatic sites in the cortex. Panels (J–L1) show colocalization of BACE1 and parvalbumin (PV) around hippocampal pyramidal somata. Note the strong BACE1 labeling in the mossy fiber terminals (mf). Abbreviations are the same as defined in Fig. 1. Scale bar = 50 µm in (A) applying to (B, C–E, F–F2, G, J–L); equivalent to 25 µm for (A1, A2, B1, E1,H, I) and 10 µm for (I1–3, L1).

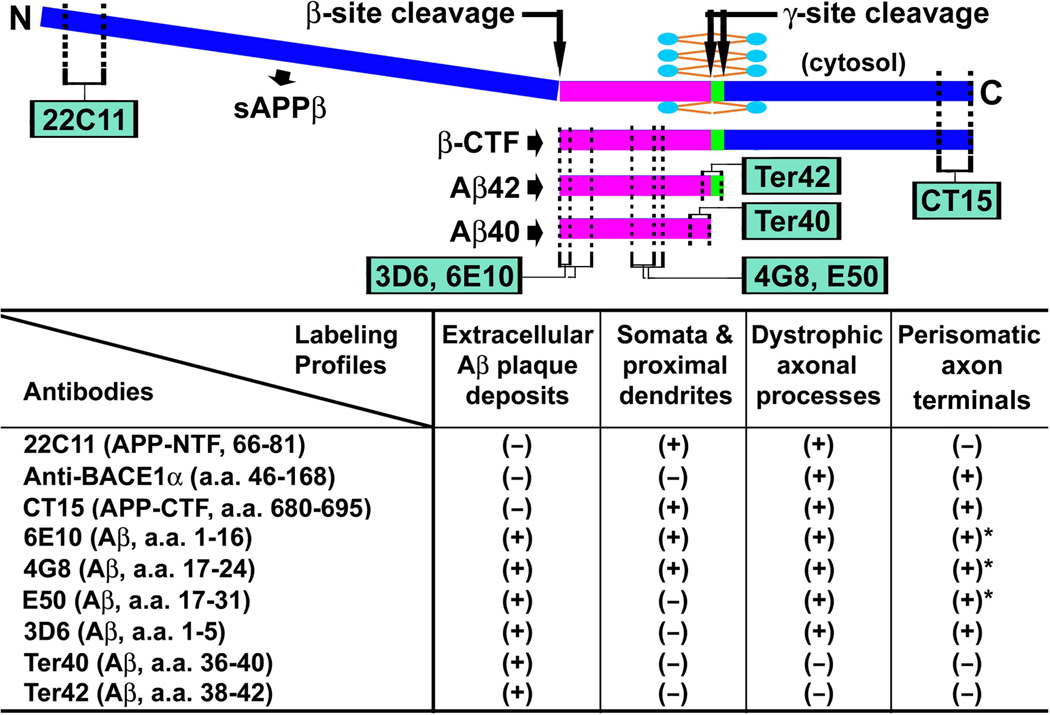

Cross-examination of axonal Aβ antibody labeling in 3xTg-AD mice

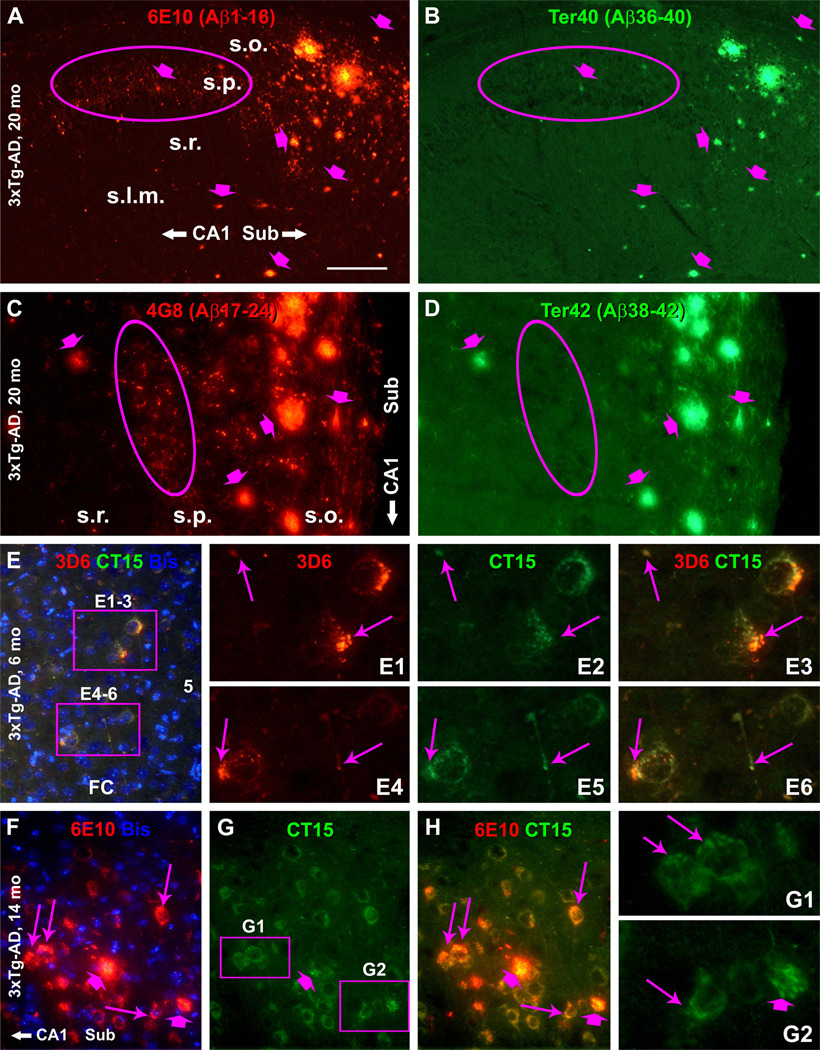

We carried out comparative immunohistochemical studies using antibodies raised against different epitopes of the Aβ domain and the APP protein to explore the nature of the early-onset Aβ antibody labeling at axon terminals. Because formic acid is known to affect Aβ antibody reactivity, we tested each antibody under conditions with mild, strong or no formic acid pretreatment. Overall, we found that with a stronger (e.g., 90% for 30 minute for 30 µm sections) or longer (e.g., 50% for 60 minutes) formic pretreatment, several antibodies (rather than 3D6) against the N-terminal (6E10) and mid-region (4G8 and E50) of the Aβ sequence could better visualize the axon terminals. Thus, 6E10 labeled perisomatic puncta and axonal processes with local swelling before and around the time of plaque onset (Fig. 3C–E1; also see S-Fig. 4F), but were abundant in 20 month-old animals, co-existing with compact and diffuse-like plaques (Fig. 4A, F). Similarly, 4G8 labeled axon terminals in young (not shown), and in 20 month-old (besides neuronal somata and extracellular plaques) transgenics (S-Fig. 3A–G). Moreover, E50 labeled these terminal profiles in young and old transgenics (S-Fig. 3H–P).

Fig. 4.

Visualization of axon terminals and processes by Aβ antibodies raised against the N-terminal (6E10, 3D6) and mid-region (4G8) of Aβ domain and β-amyloid precursor protein C-terminal (CT15), but not by antibodies against Aβ C-terminal (Ter40 and Ter42), in 3xTg-AD mice at different ages as indicated. A strong formic acid treatment (90%, 10 minutes, 6 µm-thick sections) was used to visualize 6E10 and 4G8 labeling. Note the differential labeling at the terminal-like profiles (cycled areas) but comparable labeling in the extracellular plaques (fat arrows) by the two pairs of Aβ antibodies (A–D). Panels (E–E6) show colocalization of 3D6 and CT15 labeling at perisomatic sites and in axonal processes (arrows) in the cortex. Panels (F–G2) illustrate colocalization of 6E10 and CT15 labeling at perisomatic sites (thin arrows) and small neuritic plaques (fat arrows) in CA1. Scale bar = 500 µm in (A) applying to (B–D); equal to 250 µm for (E–H) and 50 µm for E1–6, G1–2).

In contrast, two antibodies raised against the Aβ C-terminal, Ter40 and Ter42 (supposed to label Aβ40 and Aβ42), did not label neuronal somata, dendrites and the above-mentioned axon terminals. This was confirmed before and after plaque onset in sections with and without formic pretreatment. For example, in 14 month-old transgenics, Ter40 or Ter42 IR spatially matched with 6E10 IR around the newly-onset plaques in the subiculum between mirror sections (S-Fig. 4A–D). The same situation was found in immunofluorescently double-labeled sections from 20 month-old transgenics (Fig. 4A–D; S-Fig. 4E–J).

Among 3 antibodies targeting at the APP C-terminal (see Table 1), CT15 fairly distinctly labeled the perisomatic puncta and discrete swollen axons before (Fig. 4E–E6) and after plaque onset (Fig. 4F–H; S-Fig. 4K–N). CT15 also exhibited intracellular IR in pyramidal neurons, likely related to full-length APP (Fig. 4G; S-Fig. 4K–N). The monoclonal antibody 22C11 displayed clear intracellular IR. It also labeled dystrophic neurites and swollen axonal processes in the cortex and hippocampal formation, including in cortical white matter and hippocampal non-cellular layers. However, 22C11 did not visualize the perisomatic puncta as other antibodies did (S-Fig. 1K–M; S-Fig. 4O–R). Taking the data together, the early-onset perisomatic punctuate IR was revealed by antibodies (3D6, 6E10, 4G8, E50 and CT15) raised against various amino acid sequences that each could be a part of the APP β-CTF (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Summary of the differential cellular and plaque labeling by various antibodies targeting at different epitopes on β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) and its amyloidogenic proteolytic products. All Aβ antibodies label extracellular plaques. 22C11, CT15, 6E10 and 4G8 label neuronal somata and proximal dendrites. Dystrophic axons can be labeled by 22C11 and CT15, and by antibodies to Aβ N-terminal and mid-region, but not by Ter40 and Ter42. The perisomatic terminals are detected by CT15 but not 22C11, and by antibodies to Aβ N-terminal and mid-region but not Aβ C-terminal. Note that the perisomatic terminals and dystrophic axons also exhibit increased BACE1 labeling.

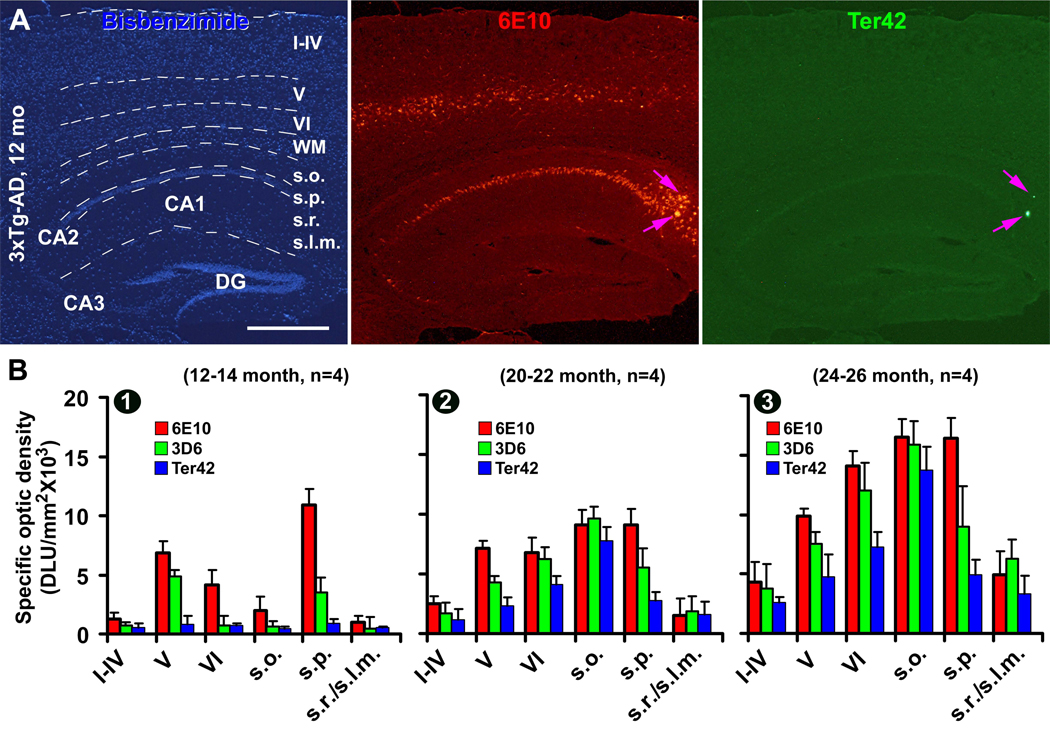

Laminar densitometric analysis of Aβ antibody labeling in 3xTg-AD mice

To quantify some of the age-related differential Aβ antibody immunolabeling, lamina-based densitometry was conducted for 3D6, 6E10 and Ter42 IR among three groups of 3xTg-AD mice, at 12–14 (n=4), 20–22 (n=4) and 24–26 (n=4) month of age (Fig. 6A–B). These age groups were chosen because there were substantial changes in the amount and distribution of immunolabeling around these age time points, as descried earlier. Parasagittal sections (12 µm-thick, 4 levels per brain, each about 400 µm apart) were fluorescently double-labeled with 3D6 vs Ter42 and 6E10 vs Ter42. Densitometry was carried out over the hippocampal CA1 region, from the s.o. to the s.l.m., and the cortical area overlying the CA1 sector, from layer I to VI. A measuring template was created over different layers in bisbenzimide-counterstained image, which was copied and applied coordinately onto the two immunofluorescent images of the same area (Fig. 6A). Optic densities obtained from batch-processed non-Tg sections were used as the cut-off levels to define the specific optic density (o.d.) in the transgenics.

Fig. 6.

Densitometry of representative Aβ antibody (6E10, 3D6 and Ter42) immunolabeling in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus in 3xTg-AD mice focusing on age-related laminar development of extracellular amyloid deposition. Panel (A) illustrates the methodology for concurrent lamina-based densitometry for two antibodies (raised in mouse and rabbit) using the OptiQuant imaging analysis software. A measuring template is created in the bisbenzimide-counterstained image, which is used to obtain optic densities of immunofluorescence over different cortical and hippocampal layers. In the 12–14 month-old group (B1), means of specific optic density of 6E10 and 3D6 immunoreactivities are high in cortical layers V and VI and hippocampal stratum pyramidale (s.p.), whereas the density of Ter42 reactivity is minimal across the cortex and hippocampus. A great increase of specific optic density occurs in the stratum oriens (s.o.) in the 20–22 month group for the 3 markers (B2). In the 24–26 month group, the deep cortex and stratum oriens show the highest density for all the 3 antibodies (B3). Abbreviations are as defined in Fig. 1.

In 12–14 month-old 3xTg-AD mice, specific o.d. of 6E10 IR was highest in the s.p. followed by layer V and VI, whereas that of 3D6 IR was highest in layer V followed by the s.p. (Fig. 6B1). In the 20–22 month group, specific o.d. of 6E10, 3D6 or Ter42 IR was increased across the cortical and hippocampal layers, with the extent of increase most prominent in the s.o., followed by layer VI (Fig. 6B2). In the 24–26 month group, means of specific o.d. of all the three markers were increased further across the cortical and hippocampal layers, most dramatic in the non-cellular layers (s.o., s.r. and s.l.m.) of the hippocampus (Fig. 6B3) (see S-Table 1 for details of age-dependent increase of mean specific o.d. in individual layers evaluated by one-way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test).

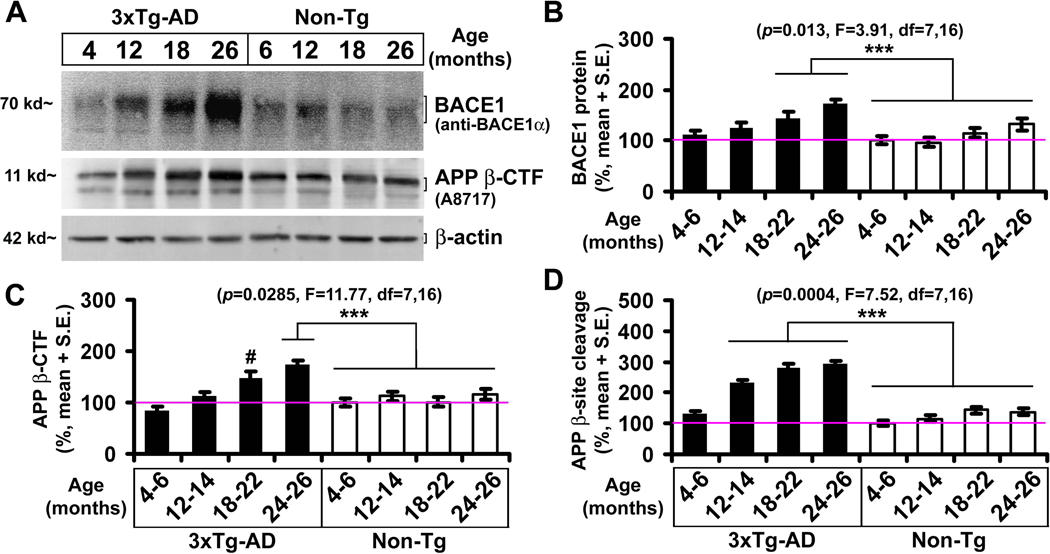

Age-related elevations of BACE1 protein, activity and APP β-CTF levels in 3xTg-AD mice

Biochemical analyses were carried out to confirm elevations of BACE1 protein, activity and β-CTF in the transgenics relative to the non-Tg counterparts in four age-groups (n=4/group). Optic density value from each brain (homogenate of one side of the cerebral cortex and hippocampal formation) was normalized to the mean of the 4–6 month-old non-Tg group. There was an age-dependent elevation of BACE1 protein levels in the transgenics (p=0.013, F=3.91, df=7,16, one-way ANOVA analysis for all sets of data), with Bonferroni posttests indicated statistically significant difference for the means of the 18–22 (143.5 ± 13.4 %, mean ± S.E.M, same format below) and 24–26 (172.8 ± 8.2) month groups relative to all the non-Tg groups (Fig. 7A, B). β-CTF levels were also elevated across-age in the transgenics (p=0.029, F=11.7, df=7,16), and the mean of the 24–26 month group (173.2 ± 20.2%) was significantly higher relative to all the non-Tg groups, whereas the mean (147.9 ± 19.7%) of the 18–22 month group was approaching statistical difference relative to the age-matched control group (p=0.16) (Fig. 7A, C). Moreover, APP β-site cleavage activity was increased with age in the transgenics (p=0.0004, F=7.52, DF=7,16). The means (231–294%) of the transgenics were higher relative to the non-Tg mice in all but the youngest groups (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Biochemical analysis on age-related elevations of BACE1protein, activity and immediate product APP β-CTF in 3xTg-AD mice relative to non-transgenic (non-Tg) cohorts. Panel (A) shows an example of immunoblotting of BACE1, β-CTF and the internal standard β-actin in cerebral hemisphere homogenates from a set of age-matched transgenics and controls. Bar graphs (B and C) show normalized mean levels of BACE1 and β-CTF in individual age groups (n=4 per group). Bar graph (D) shows levels of β-site APP cleavage activity assayed in the same cerebral extracts. Horizontal line in the bar graphs denotes the level (100%) used for data normalization. One way ANOVA analyses revealed elevations of these measurements with age in the transgenics. ***: Statistically significant difference (P<0.05) determined by Bonferroni posttests.

Discussion

3xTg-AD mice develop compact and diffuse plaques in the forebrain

Diffuse and neuritic/compact plaques are practically defined according to the pattern of Aβ deposition and presence/extent of local neuritic pathology [Thal et al., 2006; Duyckaerts et al., 2009; Castellani et al., 2010]. BACE1 appears to be an excellent marker for AD-like neuritic pathology, because dystrophic axonal neurites express BACE1 more robust than common and specific neuronal terminal markers [Zhao et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2010]. Therefore, correlative examination of BACE1 and Aβ labeling allows a differential appraisal of plaque types. 3xTg-AD mice appear to develop largely diffuse-like plaques in the forebrain during their lifespan. Thus, amyloid plaques in most cortical areas and hippocampal formation in old animals exhibit a spreading pattern, and may distribute across a fairly large area without clear unlabeled borders. These diffuse-like plaques are generally not associated with large BACE1 labeled dystrophic neurites appearing as distinct rosette-like clusters. In contrast, compact-like plaques composed of overt dystrophic neurites and dense-packed Aβ deposition develop in the subiculum and joining CA1 in 3xTg-AD mice. Overall, the pattern of age-related Aβ deposition in the 3xTg-AD model appears somewhat different from that in some other transgenic models. For instance, cortical amyloid plaques in Tg2576, 2XFAD and 5XFAD mice appear to be largely the compact/neuritic type [Hsiao et al., 1996; Borchelt et al., 1997; Zhao et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009; 2010; Bulgold et al., 2011].

However, it should be noted that diffuse-like plaques in old 3xTg-AD mice are not devoid of BACE1-labeled abnormal neuronal elements. Rather, they are associated with relatively small or terminal-like labeled profiles varying in sizes and shapes. Also of note, around some large diffuse-like plaques with a strong Aβ IR in the center, BACE1 labeled neurites show a greater extent of swollen and sprouting, and may occur as rosette-like budding apparatus typically seen in compact plaques. These observations suggest that diffuse and compact plaques are a spectrum of pathology in which the extent and morphology of Aβ deposition and neuritic alteration are variable or mixed, and might undergo dynamic changes.

Amyloidogenic axonal pathology precedes diffuse plaque formation in 3xTg-AD mice

The correlated onset and evolution of BACE1 and Aβ labeling around the subiculum in 3xTg-AD mice show the same course of compact plaque development characterized in other transgenic models [Zhang et al., 2009; 2010]. These consistent data from different mouse models of AD strengthen the notion that amyloidogenic axonal pathology plays an important role in the formation of compact/neuritic plaques [Zhang et al., 2009]. Several lines of evidence from the present study support that, as with the neuritic type, axonal structures are likely the major origin of Aβ deposits in diffuse-like plaques in 3xTg-AD mice. (1) Increased BACE1 is detected at fine axonal elements in areas with diffuse plaques in aged mice. (2) Age-related increase in labeling density of extracellular Aβ (e.g., as labeled by Ter42) occurs earlier or greater in lamina with extensive axonal alterations (swollen/sprouting), particularly notable in the s.o. that contains few neuronal somata. (3) Axonal terminal pathology inherent with BACE1 elevation appears before plaque onset in the forebrain. (4) Levels of BACE1 protein, enzymatic activity and β-CTF elevate with age in the cerebrum, suggesting a functional role of BACE1 in Aβ overproduction.

Whether compact and diffuse plaques develop independently or evolve from one to the other is one of the unsolved issues in plaque pathogenesis [Fiala, 2007; Duyckaerts et al., 2009; Castellani et al., 2010]. We hypothesize that axonal pathogenesis may govern the site-specific development of extracellular Aβ deposition regardless of plaque types. Thus, a more aggressive axonal pathogenesis, i.e., severer swollen/sprouting, may lead to Aβ deposition more likely in the compact form, because it is inherent with a greater Aβ production resulting in a rapid local Aβ accumulation [Zhang et al., 2009]. On the other hand, diffuse amyloid plaque may develop in association with a relatively mild, slow-progressing and/or multi-loci amyloidogenic axonal terminal pathology, yielding a spreading pattern of Aβ deposition. Such a notion could explain the morphology of largely diffuse-like plaques and a relatively late/slow development of these plaques in cortex of the 3xTg-AD mice relative to other models of AD [Zhang et al., 2009, 2010].

Is the early-onset Aβ antibody labeling at axon terminals a cross-reactivity of APP β-CTF?

The distinct 3D6 reactivity at perisomatic axon terminals was initially noticed in 5XFAD and 2XFAD mice, and it was interpreted as an intra-axonal Aβ labeling [Zhang et al., 2009]. However, it is increasingly debated whether intraneuronal Aβ antibody labeling reflects accumulation of Aβ inside neurons [Wegiel et al., 2007; Aho et al., 2011]. It is also puzzling that in the cortex of 3xTg-AD mice 3D6 labeling at axonal (likely presynaptic) terminals emerges very early (1–2 month of age), whereas extracellular Aβ IR is barely detectable before 20 month.

With relatively strong formic section treatment, several other antibodies targeting the N-terminal (6E10) and mid-region (4G8 and E50) of Aβ domain and an antibody against the APP CTF (CT15) show early-onset labeling at perisomatic axon terminals. However, these profiles are not detected by two antibodies against the Aβ C-terminal (Ter 40 and Ter 42), nor by the APP N-terminal antibody 22C11 (Fig. 6). This differential immunolabeling pattern appears to suggest that the early-onset axonal terminal Aβ antibody labeling may be potentially related to the immediate BACE1 product β-CTF, rather than Aβ per se (Fig. 5). If this is the case, γ-secretase cleavage of the elevated β-CTF would hypothetically lead to increased Aβ release from the axon terminals. Thus, the presence of early-onset amyloidogenic axon terminal alteration or pathology could be one of the neuronal abnormalities that account for a potential rise of soluble Aβ products in the interstitial space before plaque formation (Lublin and Gandy, 2010).

It is perhaps worth noting that perisomatic axon terminal labeling could be difficult to distinguish from perikaryal or intrasomal labeling. The early granular or punctuate BACE1/3D6 labeling in transgenic cortex and hippocampus are identified to occur at axonal terminals based on several observations. First, the labeled profiles are arranged largely around layer V and CA1 pyramidal neuronal somata, sometimes protruding beyond the cell border/outline. Second, these profiles colocalize with synaptophysin, a presynaptic terminal marker. Finally and importantly, these profiles can colocalize with interneuron markers such as parvalbumin, GAT1 and NADPH-d [Zhang et al., 2009], around cortical and hippocampal principal neurons that are excitatory and glutamatergic, excluding the likelihood that the double labeled perisomatic profiles are inside the principal neuronal somata.

In summary, the present study shows that extracellular Aβ deposition in the 3xTg-AD mice manifests largely as diffuse-like plaques in most forebrain regions, although typically as compact-like plaques around the subiculum. Early axonal terminal alterations are labeled by BACE1 and some Aβ antibodies before the development of extracellular Aβ deposition as diffuse or compact-like plaques. There is a possibility that the early-onset axon terminal Aβ antibody labeling relates to β-CTF, the immediate BACE1 product. Overall, our results suggest a close relationship between amyloidogenesis and axonal terminal pathology in transgenic models of AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Illinois Department of Public Health (X.X.Y.), National Institute of Health (1R21NS056371 to P.R.P.), Southern Illinois University Center for Alzheimer's disease and related disorders (X.X.Y., P.R.P., R.G.S.), intramural program of the National Institute on Aging (H.C.) and Central South University (X.X.Y.). We thank Elan Pharmaceuticals and Drs. H. Akiyama, H. Mori, E. Koo and P. Davis for providing antibodies.

Contributor Information

Yan Cai, Department of Human Anatomy and Neurobiology, Central South University Xiangya School of Medicine, Changsha, Hunan 410013, China; Department of Anatomy, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA; Department of Physiology, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA.

Xue-Mei Zhang, Department of Anatomy, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA; Department of Neurology, The second Affiliated Hospital, Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150086, China.

Lauren N. Macklin, Department of Physiology, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA

Huaibin Cai, Laboratory of Neurogenetics, National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Xue-Gang Luo, Department of Human Anatomy and Neurobiology, Central South University Xiangya School of Medicine, Changsha, Hunan 410013, China.

Salvatore Oddo, Department of Physiology and The Barshop Institute for Longevity and Aging Studies, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA.

Frank M. LaFerla, Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California 92697, USA

Robert G. Struble, Center for Alzheimer's disease, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Springfield, IL 62794, USA

Gregory M. Rose, Department of Anatomy, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA

Peter R. Patrylo, Department of Anatomy, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA Department of Physiology, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA.

Xiao-Xin Yan, Department of Human Anatomy and Neurobiology, Central South University Xiangya School of Medicine, Changsha, Hunan 410013, China; Department of Anatomy, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA.

REFERENCES

- Aho L, Pikkarainen M, Hiltunen M, Leinonen V, Alafuzoff I. Immunohistochemical visualization of amyloid-beta protein precursor and amyloid-beta in extra- and intracellular compartments in the human brain. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;20:1015–1028. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigl M, Apelt J, Luschekina EA, Lange-Dohna C, Rossner S, Schliebs R. Expression of beta-secretase mRNA in transgenic Tg2576 mouse brain with Alzheimer plaque pathology. Neurosci Lett. 2000;292:107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchelt DR, Ratovitski T, van Lare J, Lee MK, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Price DL, Sisodia SS. Accelerated amyloid deposition in the brains of transgenic mice coexpressing mutant presenilin 1 and amyloid precursor proteins. Neuron. 1997;19:939–945. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80974-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgold S, Bittner T, Dorostkar MM, Kieser D, Fuhrmann M, Mitteregger G, Kretzschmar H, Schmidt B, Herms J. In vivo multiphoton imaging reveals gradual growth of newborn amyloid plaques over weeks. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:327–335. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0787-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Wang Y, McCarthy D, Wen H, Borchelt DR, Price DL, Wong PC. BACE1 is the major beta-secretase for generation of Aβ peptides by neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:233–234. doi: 10.1038/85064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Xiong K, Zhang XM, Cai H, Luo XG, Feng JC, Clough RW, Struble RG, Patrylo PR, Chu Y, Kordower JH, Yan XX. β-Secretase-1 elevation in aged monkey and Alzheimer's disease human cerebral cortex occurs around the vasculature in partnership with multisystem axon terminal pathogenesis and β-amyloid accumulation. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:1223–1238. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07376.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani RJ, Rolston RK, Smith MA. Alzheimer Disease. Dis Mon. 2010;56:484–546. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyckaerts C, Delatour B, Potier MC. Classification and basic pathology of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:5–36. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0532-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GA, Tezapsidis N, Carter J, Shioi J, Bouras C, Li HC, Johnston JM, Efthimiopoulos S, Friedrich VL, Jr, Robakis NK. Identification and neuron specific expression of the S182/presenilin-1 protein in human and rodent brain. J Neurosci Res. 1996;45:308–320. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960801)45:3<308::AID-JNR13>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala JC. Mechanisms of amyloid plaque pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:551–571. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras GK, Tampellini D, Takahashi RH, Capetillo-Zarate E. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid accumulation and synapse pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:523–541. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0679-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata-Fukae C, Li HF, Hoe HS, Gray AJ, Minami SS, Hamada K, Niikura T, Hua F, Tsukagoshi-Nagai H, Horikoshi-Sakuraba Y, Mughal M, Rebeck GW, LaFerla FM, Mattson MP, Iwata N, Saido TC, Klein WL, Duff KE, Aisen PS, Matsuoka Y. Females exhibit more extensive amyloid, but not tau, pathology in an Alzheimer transgenic model. Brain Res. 2008;1216:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrup K. Reimagining Alzheimer's disease--an age-based hypothesis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16755–16762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4521-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry MC, Locascio JJ, Hyman BT. beta-site APP cleaving enzyme mRNA expression in APP transgenic mice: anatomical overlap with transgene expression and static levels with aging. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63955-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS, Wegiel J, Sapienza V, Chen J, Hong H, Wisniewski HM. Immunoreactivity of presenilin-1 in human, rat and mouse brain. Brain Res. 1997;757:159–163. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird FM, Cai H, Savonenko AV, Farah MH, He K, Melnikova T, Wen H, Chiang HC, Xu G, Koliatsos VE, Borchelt DR, Price DL, Lee HK, Wong PC. BACE1, a major determinant of selective vulnerability of the brain to amyloid-beta amyloidogenesis, is essential for cognitive, emotional, and synaptic functions. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11693–11709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2766-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov O, Lee M, Peterson DA, Sisodia SS. Evidence that synaptically released beta-amyloid accumulates as extracellular deposits in the hippocampus of transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9785–9793. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09785.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MK, Slunt HH, Martin LJ, Thinakaran G, Kim G, Gandy SE, Seeger M, Koo E, Price DL, Sisodia SS. Expression of presenilin 1 and 2 (PS1 and PS2) in human and murine tissues. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7513–7525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07513.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lublin AL, Gandy S. Amyloid-beta oligomers: possible roles as key neurotoxins in Alzheimer's Disease. Mt Sinai J Med. 2010;77:43–49. doi: 10.1002/msj.20160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrangelo MA, Bowers WJ. Detailed immunohistochemical characterization of temporal and spatial progression of Alzheimer’s disease-related pathologies in male triple-transgenic mice. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9 doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-81. article 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimplikar SW, Nixon RA, Robakis NK, Shen J, Tsai LH. Amyloid-independent mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14946–14954. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4305-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson RT, Baratta J, Yu J, LaFerla FM. Amyloid-beta expression in retrosplenial cortex of triple transgenic mice: relationship to cholinergic axonal afferents from medial septum. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1334–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng JG, Price DL, Koliatsos VE. Disruption of corticocortical connections ameliorates amyloid burden in terminal fields in a transgenic model of Abeta amyloidosis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9794–9799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09794.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struble RG, Ala T, Patrylo PR, Brewer GJ, Yan XX. Is brain amyloid production a cause or a result of dementia of the Alzheimer's type? J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:393–399. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal DR, Capetillo-Zarate E, Del Tredici K, Braak H. The development of amyloid beta protein deposits in the aged brain. Sci. Aging Knowledge Environ. 2006;6 doi: 10.1126/sageke.2006.6.re1. re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Groen T, Liu L, Ikonen S, Kadish I. Diffuse amyloid deposition, but not plaque number, is reduced in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 double-transgenic mice by pathway lesions. Neuroscience. 2003;119:1185–1197. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegiel J, Kuchna I, Nowicki K, Frackowiak J, Mazur-Kolecka B, Imaki H, Wegiel J, Mehta PD, Silverman WP, Reisberg B, Deleon M, Wisniewski T, Pirttilla T, Frey H, Lehtimäki T, Kivimäki T, Visser FE, Kamphorst W, Potempska A, Bolton D, Currie JR, Miller DL. Intraneuronal Abeta immunoreactivity is not a predictor of brain amyloidosis-beta or neurofibrillary degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113:389–402. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0191-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong K, Luo DW, Patrylo PR, Luo XG, Struble RG, Clough RW, Yan XX. Doublecortin-expressing cells are present in layer II across the adult guinea pig cerebral cortex: partial colocalization with mature interneuron markers. Exp Neurol. 2008;211:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan XX, Li T, Rominger CM, Prakash SR, Wong PC, Olson RE, Zaczek R, Li YW. Binding sites of gamma-secretase inhibitors in rodent brain: distribution, postnatal development, and effect of deafferentation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2942–2952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0092-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XM, Cai Y, Xiong K, Cai H, Luo XG, Feng JC, Clough RW, Struble RG, Patrylo PR, Yan XX. BACE1 elevation in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease is associated with synaptic/axonal pathology and amyloidogenesis: implications for neuritic plaque development. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:2271–2283. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XM, Xiong K, Cai Y, Cai H, Luo XG, Feng JC, Clough RW, Patrylo PR, Struble RG, Yan XX. Functional deprivation promotes amyloid plaque pathogenesis in Tg2576 mouse olfactory bulb and piriform cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:710–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Fu Y, Yasvoina M, Shao P, Hitt B, O'Connor T, Logan S, Maus E, Citron M, Berry R, Binder L, Vassar R. Beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 levels become elevated in neurons around amyloid plaques: implications for Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3639–3649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4396-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.