Short Summary

The primary goal of this study was to investigate how speech perception is altered by the provision of a preview or “prime” of a sample of speech just before it is presented in masking. A same-different test paradigm was developed to compare the benefit of priming in overcoming energetic and informational masking. Results demonstrated that priming was effective in improving speech perception with energetic maskers. It is less clear how much benefit from priming could be attributed to release from informational masking. Performance on the same-different task and an open-set speech recognition task with the same stimuli was linearly related.

INTRODUCTION

In everyday listening to speech, we are assisted by knowing the context of the messages we are hearing. Previous research has demonstrated that the more we know about what we will hear ahead of time the better our chances of listening successfully in adverse acoustic environments (e.g., Nittrouer & Boothroyd 1990; Dubno et al. 2000; Most & Adi-Bensaid 2001; Fallon et al. 2002; Helfer & Freyman 2008; Sheldon et al. 2008). For example, Nittrouer and Boothroyd (1990) and Dubno et al. (2000) demonstrated better key-word recognition in the high-relative to low-predictability sentences in both younger and older listeners. Helfer and Freyman (2008) showed that providing listeners with only the general topic of a sentence before presentation in masking improved speech recognition performance for both younger and older listeners. The goal of the current study is to begin to understand how listeners perceive speech when most of the uncertainty is removed. Performance in this case could serve as an upper bound on the improvement in speech recognition that can be achieved through the provision of context.

Providing the content of a message before presentation during test trials has been called “auditory priming” and has been tied to the concept of implicit memory. Words that listeners are exposed to before auditory testing, although not explicitly memorized, nevertheless improve listeners’ ability to recognize those words when presented auditorily later (e.g., Roediger 1990; Tulving & Schacter 1990; Schacter & Church 1992; Church & Schacter 1994; Schacter et al. 1994; Ratcliff et al. 1997; Ratcliff & McKoon 1997; Pilotti et al. 2000). These studies often include relatively long lists of words provided before auditory testing begins and so do not remove the trial-to-trial uncertainty such as we are seeking to accomplish.

Some research (Freyman et al. 2004; Yang et al. 2007, Ezzatian et al. 2011) investigated how priming on each auditory trial affects listeners’ ability to understand speech in the presence of masking, with a particular focus on the extent to which the benefit of priming depends on the type of masking that is introduced. For example, if speech is partially masked by stationary noise, leading to mostly what is known as “energetic masking,” priming may help us fill in the pieces that are below threshold. When speech is masked by other speech, there can under some circumstances also be an element of confusion between target and masker, leading to what is sometimes known as “informational” masking, which can coexist with energetic masking. There is reason to believe that priming could be particularly effective in overcoming the informational type of masking. This is because substantial portions of the target are presented at signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) that would normally be sufficient for audibility, but the target is nevertheless difficult to extract from the mixture. If the content of the target speech message is known ahead of time, the entangled mixture of voices seems to be perceptually reorganized. The subjective impression is that the target pops out of the mixture and the remainder moves to the perceptual background. For a better understanding of how priming can reorganize perception, consider the case of the classical drawing of a Dalmatian canine by R.C. James (In Goldstein 1996). The drawing consists of an apparently random pattern of dots and lines. However, once the viewer is primed to see the picture as a Dalmatian, it is thereafter easily perceived as a Dalmatian.

Unfortunately, the Dalmatian illustration is much more a demonstration than a measurable experimental outcome, and in general the effect of trial-by-trial priming is difficult to quantify. A simple auditory priming paradigm, e.g., presenting a sentence in quiet before a presentation in a competing background, exhibits an inherent problem. The listener could simply repeat the prime from memory, without actually listening to the target when it is presented in masking. To overcome this problem, Freyman et al. (2004) and Ezzatian (2011) in English, and Yang et al. (2007) in Chinese, presented priming nonsense sentences that were identical to the target sentences, but with white noise replacing the last of three key words. The target key word could not be obtained simply by listening to the prime. Nevertheless, when the masker was a mixture of other nonsense sentences spoken by two talkers, recognition performance for the unprimed last key word consistently improved. Freyman et al. (2004) found that this improvement averaged more than 35 percentage points across listeners at −4 dB SNR. They suggested that hearing this partial preview of the target sentence allowed the listener to segregate the target sentence from the masker utterances. Once the listeners perceptually “latched on” to the target utterance, they continued to follow it through perceptual streaming and were able to identify the unprimed last key word. For similar conditions, Yang et al. (2007) reported improvement across listeners of Chinese sentences to be more than 15 percentage points at −8 dB SNR for whole word scores and more than 25 percentage points at −8 dB SNR for scores of the second syllable of the word. When the masker was continuous noise, the improvement in performance for the unprimed key word was considerably reduced in both studies.

It could be argued that the difference in the effect of priming for the two types of maskers was not due to a difference in the effectiveness of priming per se, but instead due to the processes involved in transferring the improved intelligibility of the first two key words to the last (test) key word. For hearing and understanding the target in the presence of the two-talker masker the problem was partially one of confusion, and once the target was highlighted the confusion was largely resolved, allowing the last key word that was not primed to also stand out through processes related to auditory streaming. In the case of the noise masker, it is assumed that misperception of the last key word was due to insufficient audibility. Even if priming was effective in improving the intelligibility of the first two key words, it is not obvious how streaming would increase the audibility of the last key word, especially because there were no semantic context cues in these nonsense sentences. Thus, in our opinion, the previous studies were not able to discern if priming is effective in overcoming the energetic type of masking.

To study the effect of priming on informational and energetic masking more directly, the current study departed from the earlier method of priming only a portion of the target. Instead, on half the trials the entire sentence was primed with text printed on a computer screen, whereas the other half served as foil trials in which one of the three key words differed from what was provided in the preview. The listeners’ task was simply to determine whether the sentence that was heard during the trial was the same as what was presented during the priming interval. It was assumed that to the extent that priming of a nonsense sentence was effective, it would be helpful in detecting the difference when one of the words in a sentence had changed. Performance in this priming condition was compared to a condition in which the provision of the correct sentence, or the sentence with one key word changed, followed the auditory presentation of the utterance. The task was exactly the same; only the order of presentation was different. The effectiveness of priming was measured by comparing performance on the two orders of presentation. Listeners read rather than heard the priming sentence, as Freyman et al. (2004) found that it did not matter whether the prime was delivered by the same talker as the target talker, by a different talker, or in printed form.

The goal of this study was to determine whether the effect of priming could be demonstrated with this method, and, if so, to compare the effectiveness with different types of maskers, those that were presumed to be purely energetic and those that were assumed to lead to informational masking as well. Three different maskers were used: a mixture of two talkers reciting nonsense sentences, a continuous noise shaped with the long-term spectrum of the two-talker masker, and a noise designed to follow the spectrotemporal variations in the two-talker masker. This latter noise was included to help resolve whether any differences in results might occur between the speech masker and the steady noise masker due to large differences in the degree of spectrotemporal fluctuation between the two types of maskers.

In some variations the masker was presented from two loudspeakers with a 4-ms delay between them to shift the perceived location away from the target using the precedence effect. Improved performance in these conditions was taken as an indication of informational masking in the non-spatially separated condition, because earlier studies have shown that this type of spatial separation leads to improved speech recognition performance only with speech maskers, not with steady or fluctuating noise maskers (e.g., Freyman et al. 1999, 2001; Li et al. 2004, Brungart et al., 2005; Rakerd et al., 2006). As a secondary goal, we sought to determine whether the same-different test paradigm used in this study produces results that are predictive of conventional open-set speech recognition testing. Data from the current experiments were compared with previous open-set data obtained using the same target sentences in the presence of the same two-talker masker.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Stimuli

The target stimuli were from a corpus of 320 nonsense sentences developed by Helfer (1997) and spoken by a college-aged female native speaker of standard American English. These sentences were syntactically but not semantically correct and contained three key words, e.g., “The shop can frame a dog.” Each key word was used only once within the corpus. These stimuli have been used in previous experiments (Helfer, 1997; Freyman et al. 1999, 2001, 2004) and have the flow of conversational speech, but key words cannot be determined from the semantic context of the sentence. The stimuli were originally recorded on digital audiotape in a sound-treated room. The analog output from the tape recorder was low-pass filtered at 8.5 kHz and digitally sampled at 20 kHz using a 16-bit analog-to-digital converter (TDT AD1) for storage on computer disk. In the current study, 20 of the 320 recorded sentences were initially reserved for practice stimuli, 15 of which were actually used (5 for each of 3 listening conditions). Replacement words (foils) were developed for all key words in the sentences. In foil trials, one key word selected from the three possible sentence positions was replaced by a foil word before presentation in the form of text on a computer monitor. Foil words were chosen according to the following rules: 1) foils cannot rhyme with the target word, 2) foils have the same number of syllables as the target word, 3) foils have the same stress pattern as the target word, 4) foils are not pronounced with more than one stress pattern, 5) no foil can be used more than once, 6) foils do not make sense in the context of the sentence, and 7) foils are the same part of speech as the target word (e.g., verbs were replaced with verbs, etc.)

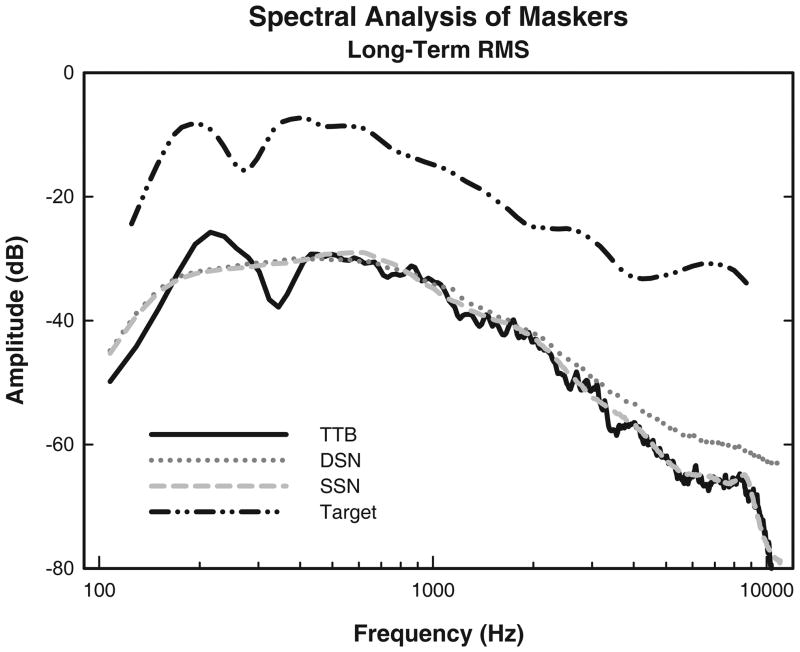

Three maskers were used in this experiment: 1) A 35-s long female two-talker babble (TTB). The two different talkers and nonsense sentences used in this masker were different from the talker and sentences used for the target stimuli. Pauses between sentences were removed using audio editing software to create a 35-s long continuous stream from each masking talker, which were then matched in rms amplitude and combined. This masker demonstrated the greatest benefit for speech recognition in the spatial condition as compared with the non-spatial condition in a previous experiment (Freyman et al. 2007). 2) A steady-state speech-spectrum noise (SSN). This masker was produced by digitally signal processing the original TTB masker with 10th-order linear predictive coding (LPC) to extract the long-term spectrum of the stimuli, then shaping white noise with the extracted spectral envelope. 3) A dynamic speech-spectrum noise (DSN) also referred to as “synthesized whispered speech.” This masker was derived from the original phonated TTB masker. The spectral envelope was extracted and digitally signal processed with a 14th-order LPC technique using a 10-ms window with a 5-ms overlap. Then white noise was modulated with the extracted spectral envelope. The digital signal processing techniques used to create the SSN and DSN maskers were described by Kong and Zeng (2006). Extraneous low-frequency noise below 150 Hz was attenuated in both SSN and DSN stimuli using a 6th-order Butterworth high-pass filter. After processing, the noise maskers were spectrally analyzed in CoolEditPro 2.0 and compared with the original TTB masker. All three maskers were found to be similar in spectral content, both in long-term RMS and in random 10-ms samples (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Long-term spectra of the target (offset +20 dB to facilitate comparison), the female two-talker speech babble (TTB) and the two noise maskers (DSN and SSN) created by digitally signal processing the TTB masker.

Apparatus

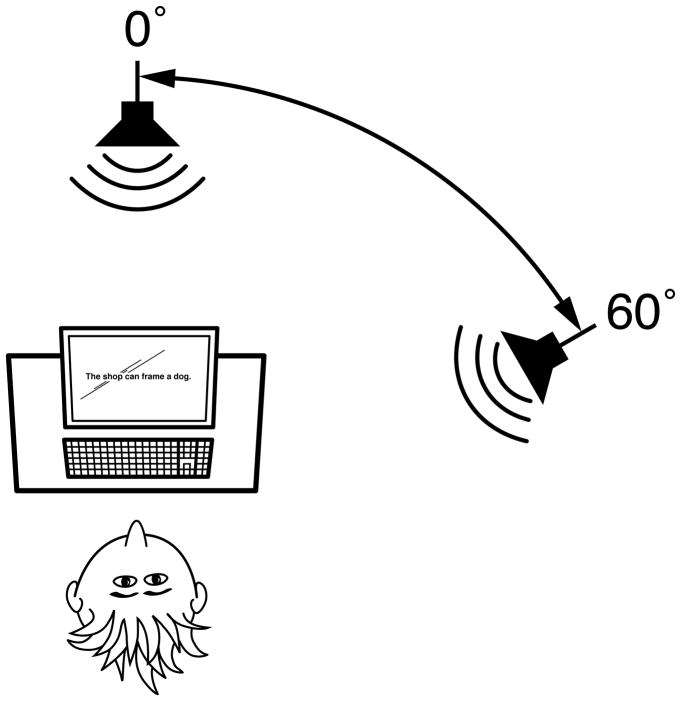

This experiment was conducted in a double-walled sound-treated booth (IAC #1604) measuring 2.76 m × 2.55 m. Reverberation characteristics of this test booth range from 0.12 s in the high frequencies to 0.24 s in the low frequencies (Nerbonne et al. 1983). Listeners sat on a chair placed against one wall of the booth and were instructed to face the front loudspeaker, but were not physically restrained. Two Realistic Minimus 7 loudspeakers were positioned at a distance of 1.3 meters from the approximate center of the subject’s head (1.2 meters high). One loudspeaker was positioned directly in front (0° azimuth) and one was positioned to the right (60° azimuth) of the listener (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Experimental apparatus in the sound attenuated booth, with loudspeakers at 0° and 60° relative to the listener’s head, a computer monitor (well below ear level) for viewing the primes, and a keyboard for typing responses.

For each auditory stimulus presentation (1.12-s to 2.11-s duration), the target and masker were digitally mixed on a computer at the required SNR and output through a two-channel sound card, attenuated (TDT PA4), amplified (TDT HBUF5), power amplified (TOA P75D), and delivered to the loudspeakers. Text was presented either before (prime) or after (control) the auditory presentations for 3.5-s via a computer monitor positioned in the sound-treated booth directly in front of the listener, but well below ear level so as not to interfere with the direct wave from either sound source. Subjects were prompted to enter a response by the appearance of “Were the sentences the same? Type Y/N:” on the computer monitor immediately following each trial. There was a 1.5-s interval between text and auditory presentations and a 2.5-s interval between a subject response and the next trial with no feedback provided. During the auditory portion of each trial the masker was initiated first, followed by the presentation of the target 0.5-s later. At the conclusion of the target sentence, the masker was terminated simultaneously. On each trial a section of masker waveform was selected randomly from the 35-s stream. The masker onset could occur anywhere in the stream.

Conditions

In a test paradigm that had originally been used by Freyman et al. (1999), both target and masker were presented from a front (0° azimuth) loudspeaker in the reference condition (F-F), where there is no spatial separation between target and masker. In the experimental condition, the target was presented and heard from the front, while the masker was presented from the front and right (60° azimuth) loudspeakers with the right leading the front by 4 ms (F-RF). Although the masker was presented from both loudspeakers at the same level, it was heard well to the right because of the precedence effect (Wallach et al. 1949), in which the direction of localization is determined by the sound source that arrives at the ear first. This precedence effect or spatial condition provides the illusion of spatial separation, while minimizing listening advantages from head shadow and binaural interaction.

The experimental parameters in the current study were: 1) masker type (TTB = two-talker babble, SSN = steady-state speech-spectrum noise, and DSN = dynamic speech-spectrum noise), 2) spatial separation (F-F = no separation; target and masker both from the front loudspeaker versus F-RF = perceived spatial separation; target from the front, masker from the right with a 4-ms lead and from the front), 3) SNR (−14, −10, −6, −2 and +2 dB), and 4) priming (c = control; sentence viewed as text on the computer monitor after the auditory presentation versus p = primed; sentence viewed as text on the computer monitor preceding the auditory presentation). In both primed and unprimed conditions, half of the sentences viewed on the monitor contained foils. The nominal values of SNR reported in the figures are those for single sources of target and interference (i.e., the F-F condition). For the F-RF condition the masker was presented from two loudspeakers, increasing its relative level in comparison to the target. However, no adjustment was made in the labeling of the SNRs for these conditions.

There were four different combinations of spatial separation and priming. Each of these conditions was presented with one of the three masker types and all five SNRs.

In the baseline condition (F-Fc; non-spatial, control) there were no listening advantages available from spatial separation or priming. Listeners were first presented with an auditory target sentence, then immediately shown a sentence displayed on a computer monitor that either matched the target sentence or contained one of three possible foil words. Example: Auditory presentation = “A rose could paint the fish.” Screen presentation = “A rose could paint the fish.” or in a non-matching foil trial “A rose could paint the bat.” In this case the third key word has been chosen for replacement from the three possible key words “rose,” “paint,” and “fish.”

The primed condition (F-Fp; non-spatial, primed) was created to examine the “priming effect.” In this condition the matching (non-foil trial) or non-matching (foil trial) sentence was displayed on the monitor immediately preceding the auditory presentation, and there was no spatial separation between target and masker.

The spatial condition (F-RFc; spatial, control) was created to examine the “spatial effect” by providing only the spatial information and not the prime. In this condition, the display of the sentence on the monitor immediately followed the auditory presentation and the perception of spatial separation was created between target and masker by presenting the masker from two loudspeakers (front and 60° right) and imposing a 4-ms delay in the masker arriving from the front loudspeaker. This resulted in the target being heard from the front while, because of the precedence effect, the masker was heard well to the right.

A spatial-primed condition (F-RFp; spatial, primed) utilizing both priming and spatial effects was created for a follow-up experiment to see if there was an additive effect of priming and perceived spatial separation when the masker was TTB. This condition was run with the baseline (F-Fc) and spatial (F-RFc) conditions.

Twenty-four native-English-speaking college students with normal-hearing (audiometric thresholds ≤ 20 dB HL at 500, 1000audiometric thresholds ≤ 20 dB HL at 500, 2000, 4000, and 6000 Hz) participated in the study. All subjects listened to 270 target sentences spoken by a female talker. Different groups of six subjects were used for each masking condition (TTB, SSN, DSN) with experimental condition (F-Fc, F-Fp, F-RFc) as a within-subject variable. Another group of six subjects participated in the follow-up experiment (F-RFp with TTB masker). Five SNRs (−14, −10, −6, −2 and +2 dB) were used in each condition, defined as target rms amplitude relative to masker rms amplitude. SNRs were manipulated by changing the level of the masker for a fixed-level target, which was always presented at 52 dBA. The level of the target stimuli presentation, determined through pilot experimentation, was set below the level of average conversational speech, but where it was still quite audible. This allowed the investigators to maintain a comfortable listening level in the −14 dB SNR masker conditions. Calibration was conducted at the beginning of each day of testing by presenting the speech-spectrum noise (SSN) through the experimental apparatus and measuring the output with a handheld sound meter (fast response, A-weighting) from each speaker individually at the average center position of a listeners head while seated in the chair of the test booth.

The 270 target sentences were selected at random from a corpus of 300 sentences, without replacement, and with a different random order for each listener. There were three blocks of 90 sentences each (F-Fp; F-Fc; and F-RFc), counterbalanced across subjects using 6 different orders. In the follow-up experiment, an F-RFp block was substituted for the F-Fp block. Each block was divided into 18 sentences for each SNR. Within each set of 18 sentences, 9 contained foils and 9 did not contain foils. Of the 9 foil trials, 3 replaced the first key word, 3 replaced the second key word, and 3 replaced the third key word. Presentation of SNRs, foil vs. non-foil trials, and sentence position of the foil words were randomized and different for each listener. All subjects completed the experiment in one session, requiring approximately one hour of participation from each subject.

The task for the listener in all conditions was to judge whether the sentence displayed on screen matched the auditory target and respond via computer keyboard, typing “y” for yes they are the same or “n” for no they are not the same. Subjects were instructed that they would be listening in three different conditions and the target sentence would always come from the front loudspeaker, but they were not given the order in which the conditions would be presented. Subjects were given five listening clues. They were instructed as follows. “When the sentences are different: 1) there will be one changed word that could be at the beginning, middle, or end of the sentence, 2) the replaced words will not rhyme with the target words, 3) half of the trials are indeed different (foils), 4) the target always begins 0.5s after the masker, and 5) if you feel it improves your performance, please rehearse the sentence in your head or out loud.”

The last instruction was presented as optional, given primarily to encourage best performance. Subjects were presented with 15 practice trials to familiarize them with the task before beginning the experiment. The practice block consisted of one trial at each of the five SNRs in each of the three listening conditions. Target sentences used in the practice trials were not included in the experimental set, and all subjects were presented with the same practice sentences.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overall Percent Correct

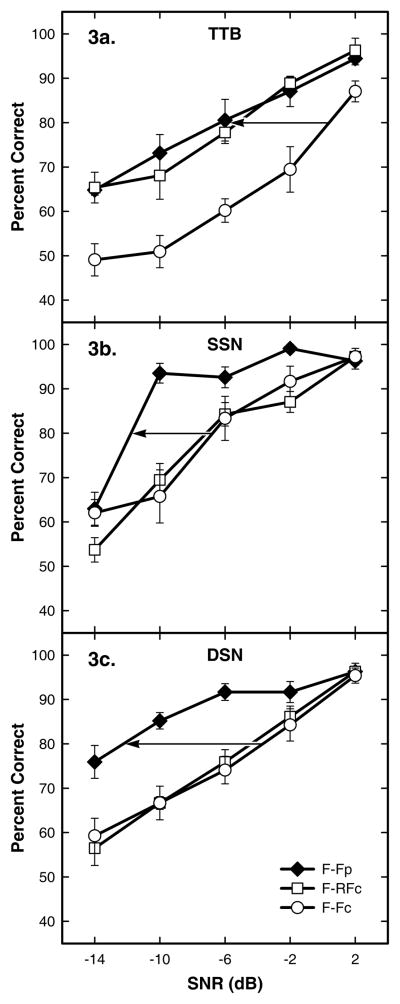

Figure 3 shows percent correct discrimination averaged across six listeners as a function of SNR for the three types of maskers (Fig. 3a: TTB; Fig. 3b: SSN, Fig. 3c: DSN). The three traces within each panel represent different spatial and/or priming conditions. Each data point is based on 108 trials across the six subjects (18 trials per subject). In the TTB masker (Fig. 3a), all subjects demonstrated performance in the F-Fp condition similar to performance in the F-RFc condition, both of which were better than performance in the F-Fc condition. In the SSN and DSN maskers (Fig. 3b and Fig. 3c), all subjects performed better in the F-Fp condition compared to the F-RFc and F-Fc conditions, with the exception of one subject in the SSN masker who performed substantially better on the F-Fc condition than the other subjects. A repeated measures ANOVA with Greenhouse-Geisser adjustment showed significant main effects for listening condition and SNR for TTB [cond = F(2,10) = 48.57, p < 0.005; SNR = F(4,20) = 41.48, p < .005], SSN [cond = F(2,10) = 17.07, p < 0.005; SNR = F(4,20) = 58.30, p < .005], and DSN [cond = F(2,10) = 24.75, p < 0.005; SNR = F(4,20) = 53.37, p < .005]. A comparison of the data across the three panels reveals one clear difference and one clear similarity among them. The difference is that the spatial masker in the control configuration (F-RFc) provided a benefit relative to the non-spatial configuration (F-Fc) only for the TTB masker, as shown in the top panel. That is, the square symbols are well above the circles in the top, but not the lower panels. For the two different noise masker conditions shown in the lower two panels, performance in the spatial and non-spatial control configurations (squares and circles) was not systematically different.

Fig. 3.

Group mean-percent correct scores as a function of SNR for the non-spatial primed (F-Fp; closed diamonds), spatial control (F-RFc; open squares), and non-spatial control (F-Fc; open circles) conditions with the two-talker babble (Fig. 3a. TTB; n=6), speech-spectrum noise (Fig. 3b. SSN; n=6), and dynamic speech-spectrum noise (Fig. 3c. DSN; n=6). Arrows indicate horizontal shift at the 80% correct point. Error bars represent ±1 standard error of the mean.

The benefit of providing spatial cues with the TTB masker is consistent with the results of Freyman et al. (2007) for this same target/masker combination and has been explained by assuming that the TTB masker produces informational masking in the non-spatial configuration that is largely relieved when target/masker spatial differences are supplied. The absence of a spatial effect with the SSN masker (Fig. 3b) is consistent with other data using unmodulated noise maskers (Freyman et al. 2001), and has been explained by a presumed dominance of energetic masking when speech is partially masked by steady noise. The F-RF configuration with a 4-ms delay has been shown not to provide cues that lead to significant release from energetic masking (Freyman et al. 1999; Brungart et al., 2005; Rakerd et al., 2006). The absence of spatial release with the spectrally and temporally fluctuating noise masker (DSN, Fig. 3c) is also consistent with earlier results (Freyman et al., 2001) and suggests that this masker also produced little informational masking.

Consistent with the above explanations, the difference in spatial release from masking across the three types of maskers seems to be governed by performance in the non-spatial (F-Fc) condition, where informational masking is presumed to exist only with the TTB masker. This is revealed by examining the data for the F-Fc condition across the three panels. Performance in the F-Fc condition, represented by the open circles, was lower with the TTB masker (Fig. 3a) than with the other two types of maskers. In contrast, the data for the spatial F-RFc condition, represented by the open squares, was not very different across the three types of maskers.

The primary similarity in the data across the three types of maskers is the effect of priming, which can be observed by comparing the closed diamonds (F-Fp) with the open circles (F-Fc) in each of the three panels. Substantial benefits of priming were measured for all three maskers. The effect was quantified by estimating the change in SNR required for criterion performance in the priming versus no priming condition. A criterion of 80% correct was chosen because it was close to the middle of the performance range. SNR shifts of 6.7, 5.0, and 8.6 dB for the TTB, SSN, and DSN maskers respectively were calculated using linear interpolation along the functions and are indicated by horizontal arrows in each panel. The importance of these exact values should not be overemphasized, as the shift in effective SNR due to priming clearly depends on the performance criterion chosen, because the slopes in the primed condition (F-Fp) tend to be shallower than for the unprimed condition (F-Fc). Nevertheless, it is evident that there was no systematic tendency for the effect of priming to be larger for the TTB masker, which presumably produced more informational masking than the noise maskers that were assumed to produce mostly energetic masking.

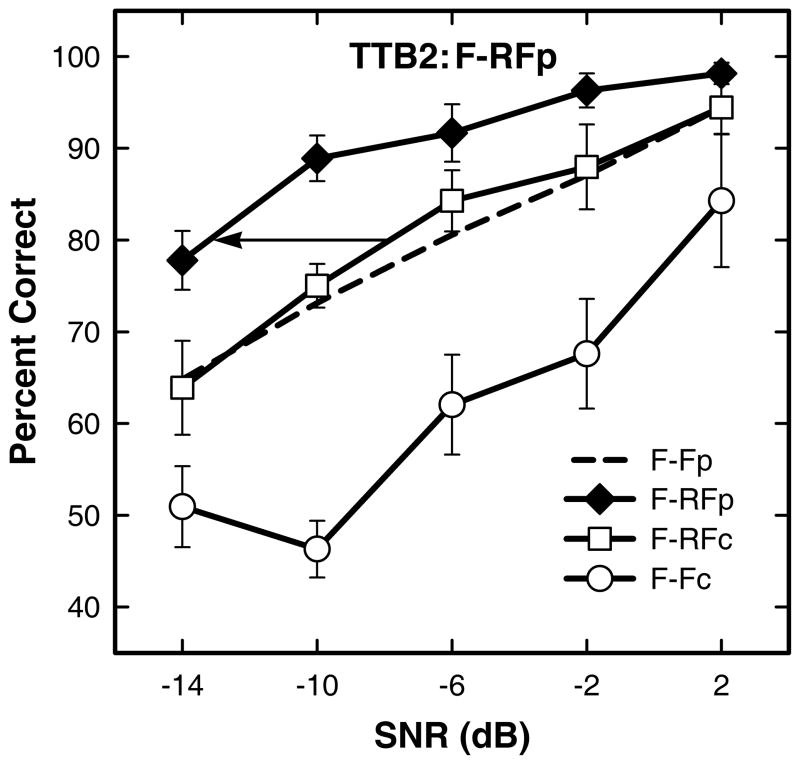

The data shown in Figure 4 provide further insight into the role of priming in overcoming energetic masking. The purpose of this sub-experiment was to evaluate the effect of priming for the speech masker when it was presumably producing mostly energetic masking. When presented in the spatial (F-RF) condition, confusability between the target and the two-talker (TTB) masker was likely to be greatly diminished, and the remaining masking is presumed to have been largely energetic. As indicated in the methods section, a separate group of subjects (n=6) was tested. The baseline condition (F-Fc) and the spatial condition (F-RFc) were repeated with these subjects to facilitate comparisons between different experimental conditions within subjects. Results in these two conditions are similar in Figure 3a and Figure 4 between the two groups of subjects. Results from the new condition (F-RFp), in which the subjects were provided with both priming and spatial cues, are indicated with closed diamonds. For all subjects except one, performance with both cues present was better compared to spatial cues alone. The one outlying subject performed similarly well in both F-RFc and F-RFp listening conditions, resulting from better overall performance in the F-RFc condition. In the comparison of interest between F-RFp and F-RFc listening conditions, a repeated measures ANOVA with Greenhouse-Geisser adjustment showed significant condition [F(1,5) = 8.83, p < 0.05] and SNR [F(4,20) = 29.33, p < 0.001] main effects, with non-significant condition × SNR interaction [F(4,20) = 1.72, p > 0.05]. Group performance in this experiment suggests that there was an additive effect of spatial and priming cues in the TTB masker, and that priming was releasing masking (presumed to be mostly energetic) that remained after informational masking had been released by spatial cues. The effect on percent correct scores was not enormous, but the shallow slopes create substantial differences in SNR for equivalent performance. The difference in SNR for 80% correct performance was 5.4 dB, not too different from the 6.7 dB obtained in Figure 3a for the non-spatial condition, when both energetic and informational masking were assumed to exist. The total improvement from both priming and spatial differences compared to the baseline F-Fc condition was substantial. For example at −10 dB SNR, performance climbed from chance to about 90% correct from a combination of both manipulations.

Fig. 4.

Group mean-percent correct scores (n=6) as a function of SNR for the spatial primed (F-RFp; closed diamonds) condition, along with additional data for the spatial control (F-RFc; open squares), and non-spatial control (F-Fc; open circles) conditions with the two-talker babble (TTB2 is the same masker used in Fig. 3a with a different group of subjects). The non-spatial primed data from Figure 3a are plotted here for comparison (dashed line). Arrow indicates horizontal shift at the 80% correct point. Error bars represent ±1 standard error of the mean.

Whereas Figure 4 shows directly that priming provided benefit beyond spatial cues alone, the corollary is also true that spatial cues provided benefit beyond priming alone. To illustrate, the data from the F-Fp condition from Figure 3a are plotted with a dashed line in Figure 4. This is now a between-subjects comparison showing the similarity in performance between the effect of priming alone (dashed line) and the effect of spatial cues alone (open squares), reinforcing the similarity observed in the within-subjects comparison displayed in Figure 3a for the same conditions. It also allows us to observe that priming with spatial cues (closed diamonds) provided a substantial benefit over priming alone (dashed line) in this between-subjects comparison. The significance of this, as mentioned above, is that the type of spatial cues provided have only been shown to help release informational masking, not energetic masking. This suggests that there must have been significant informational masking remaining even after priming.

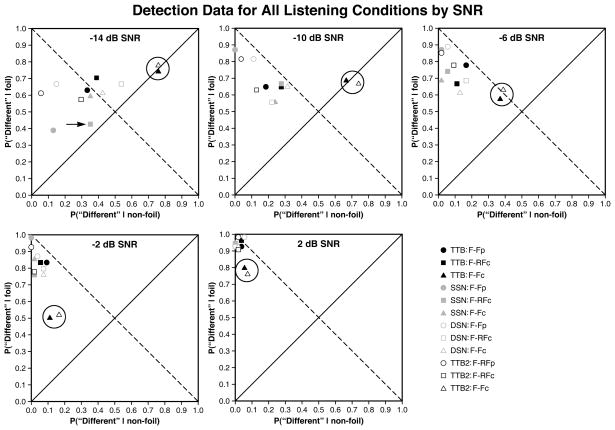

Accuracy versus Bias

Analysis was performed to separately examine accuracy and response bias in this experimental design. A “hit” was recorded when the auditory sentence was different from the sentence viewed on the computer monitor (foil trial), and the listener responded that they were different. A “false alarm” was recorded when the auditory and orthographic presentations of the sentence were the same (non-foil trial), but the listener responded that they were different. Group mean (n=6) hit and false alarm rates were calculated for each listening condition and plotted for each SNR in Figure 5. In the most difficult listening condition of −14 dB SNR, the data points are scattered and several fall towards chance performance (solid diagonal line). As the listening conditions become easier the data points migrate toward the upper left corner, indicating a high level of sensitivity in the 2-dB SNR condition. With only a few exceptions, this migration occurred without large shifts in response bias; both within and across panels, most data points remained to the left of the minor diagonal, indicating a consistent bias toward “same” responses, with low false-alarm rates (“different” responses for non-foil trials). Therefore, there were more correct responses on non-foil trials. One might expect this in priming conditions, because these non-foil trials were the ones where the entire sentence was primed. However, the bias also occurred for the control conditions where the written sentence followed the auditory presentation. As pointed out by Macmillan and Creelman (2005, page 218), a bias in this direction is quite common, attributed to subjects naturally saying “same” when a pair is hard to discriminate.

Fig. 5.

Signal detection data. Group mean (n=6 for each listening condition) hit [P(“Different” | foil)] and false alarm [P(“Different” | non-foil)] rates are plotted for all listening conditions and for each SNR. Closed black symbols = TTB masker, closed gray symbols = SSN masker, open gray symbols = DSN masker, open black symbols = TTB2 masker (same masker as TTB, but data are from a second group of 6 subjects).

The primary exception to this bias was TTB F-Fc (circled triangles) at the poorer SNRs. At −14 dB SNR, the data reveal chance performance and a clear tendency for listeners to respond with “different.” The reason for this bias is not known, but it should be recognized that even when the target was mostly inaudible the listener heard a masker consisting of a mixture of voices. In this condition, listeners may have assumed that had the words they read been present in the preceding auditory stimulus, they would have heard them, and so responded with “different” when they did not hear them. It may be worth noting that one of the noise masker conditions (SSN F-RFc) also resulted in performance that was near chance at −14 dB SNR, but a bias toward responding with “different” was not observed (grey square indicated by the arrow). Listeners showed a slight bias toward responding with “same” in this condition where they heard a steady masking noise and presumably barely audible speech.

For the TTB masker in the F-Fc condition (circled triangles), improvements in performance with increasing SNR were largely governed by decreases in false-alarm rates. As SNRs increased from −14 dB to −2 dB, the hit rate actually decreased slightly and the false-alarm rate decreased markedly, indicating improved accuracy and, like the other conditions, a bias toward “same” responses. Recall that the masker level changed from trial to trial with the target level fixed in order to vary SNR between trials. It cannot be determined from the current data that the same pattern of biases across SNRs would have been observed had the masker been fixed in level and the target varied. Finally, it may be worth noting that these encircled triangles represent the means of two different groups of 6 subjects listening to the TTB F-Fc condition, yet the two data points move similarly as SNR changes, indicating consistent and repeatable results in both accuracy and bias between subject groups.

Foil Position Effects

Foil trials were analyzed further by the position of the foil words in the sentences and are displayed in Tables 1–4. The data were collapsed across SNR, as there were only 9 foil trials per listener at each SNR for a given condition, and therefore only 3 trials for each of the 3 foil positions. The collapsed data in the table are based on 90 total trials (3 trials per SNR × 5 SNRs × 6 listeners). In each table, the means for the experimental and control conditions are shown and then the differences between them.

TABLES 1–4.

Analysis of foil position effects.

Group mean data (n=6 for each masking condition) from foil trials were collapsed across SNR for each foil position (Pos.) in all listening conditions. Comparisons between priming and baseline (left tables) and spatial separation and baseline (right tables) are displayed with differences (Diff.) calculated in the right column of each table.

| Table 1 (Effect of Priming) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masker | Pos. | F-Fp | F-Fc | Diff. |

| TTB | 1 | 67.78 | 58.89 | 8.89 |

| 2 | 78.89 | 57.78 | 21.11 | |

| 3 | 82.22 | 81.11 | 1.11 | |

| SSN | 1 | 82.22 | 76.67 | 5.56 |

| 2 | 81.11 | 65.56 | 15.56 | |

| 3 | 78.89 | 75.56 | 3.33 | |

| DSN | 1 | 83.33 | 74.44 | 8.89 |

| 2 | 81.11 | 52.22 | 28.89 | |

| 3 | 88.89 | 86.67 | 2.22 | |

| Table 2 (Effect of Spatial Separation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masker | Pos. | F-RFc | F-Fc | Diff. |

| TTB | 1 | 74.44 | 58.89 | 15.56 |

| 2 | 64.44 | 57.78 | 6.67 | |

| 3 | 90.00 | 81.11 | 8.89 | |

| SSN | 1 | 77.78 | 76.67 | 1.11 |

| 2 | 62.22 | 65.56 | −3.33 | |

| 3 | 72.22 | 75.56 | −3.33 | |

| DSN | 1 | 70.00 | 74.44 | −4.44 |

| 2 | 58.89 | 52.22 | 6.67 | |

| 3 | 88.89 | 86.67 | 2.22 | |

| Table 3 (Effect of Priming) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masker | Pos. | F-RFp | F-RFc | Diff. |

| TTB2 | 1 | 75.56 | 72.22 | 3.33 |

| 2 | 85.56 | 61.11 | 24.44 | |

| 3 | 90.00 | 82.22 | 7.78 | |

| Table 4 (Effect of Spatial Separation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masker | Pos. | F-RFc | F-Fc | Diff. |

| TTB2 | 1 | 72.22 | 60.00 | 12.22 |

| 2 | 61.11 | 58.89 | 2.22 | |

| 3 | 82.22 | 82.22 | 0.00 | |

Results revealed classical serial position effects, in which salience is greater for the most recent stimuli (recency effect) and for the initial stimuli (primacy effect) compared to stimuli in the middle position (e.g., Deese & Kaufman, 1957; Murdock, 1962). In the most basic control condition (F-Fc in Tables 1, 2, and 4), performance in position 3 was substantially better than position 2, which is consistent with the recency effect. For the two noise maskers, there was also a primacy effect, i.e., performance for position 1 was better than position 2. No primacy effect was observed for the speech (TTB) masker in the F-Fc condition, possibly because confusion between target and masker may be greatest when the target was first turned on. This absence of a primacy effect for TTB was replicated in the additional group of subjects whose data are shown in Table 4. These positional effects appear to be consistent with those reported by Ezzatian et al. (2008), also using nonsense target sentences with three key words and similar types of maskers.

For all three maskers, the effect of priming was greatest by far for position 2 (Table 1), averaging more than 20 percentage points across the different maskers. In contrast, when there was a benefit of spatial separation on overall performance (TTB only), the benefit was mostly for position 1 (Table 2). This result was replicated with the fourth subject group (Table 4). Spatial separation may have resolved the confusion between target and masker at the beginning of the auditory trial, allowing the same primacy effect found with the noise maskers to be observed with the TTB masker also. When spatial separation and priming were combined and compared with spatial separation alone, a similar improvement in responses to foils in position 2 was observed (Table 3), the same type of outcome as when there was no spatial separation (Table 1).

Overall, it appears that priming and spatial separation had different effects on these foil trials, even though the improvement in overall performance observed in Figure 3a was highly similar. When informational masking was thought to be a substantial component of the total amount of masking, spatial separation restored the primacy effect for foils in position 1. In contrast, priming improved performance with position 2 foils both in the condition containing informational masking (TTB F-Fc), and in those thought to be mainly energetic masking, i.e., the noise maskers and the spatially-separated TTB masker.

Potential Applications

The same-different task used for these experiments appears to hold promise as a measure of speech recognition when compared to conventional methods. Rankovic and Levy (1997) investigated listeners’ ability to estimate articulation scores using orthographic representations of the nonsense syllable stimuli displayed on a computer monitor either simultaneously with the auditory presentation or 500 ms after the auditory presentation. Most subjects overestimated actual scores in the simultaneous presentation, suggesting the possibility that they may have actually been hearing the speech sounds better in this condition. The current data are consistent with this finding. The estimation procedure by Rankovic and Levy requires much less time to administer than traditional test procedures and therefore may hold potential for clinical and research applications.

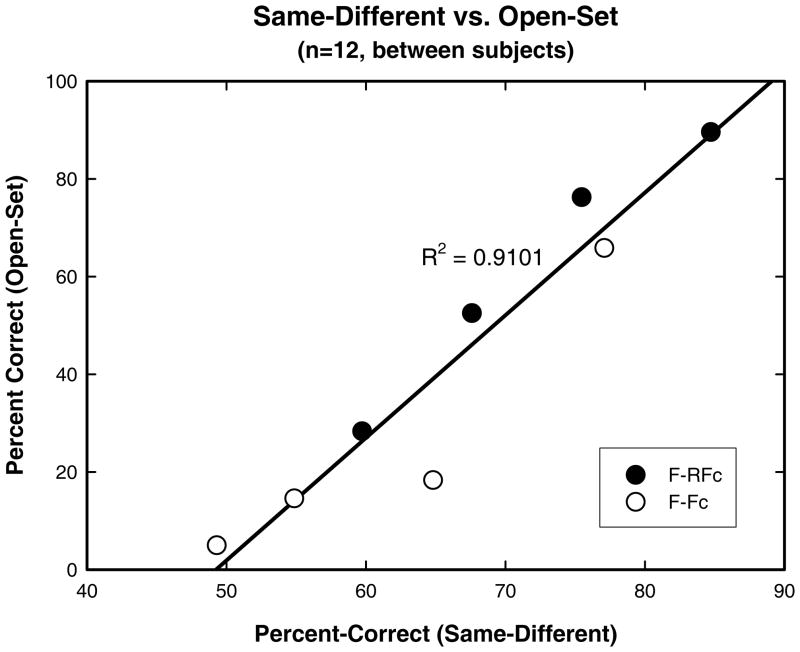

Similarly, the same-different test paradigm used in this study is extremely easy to administer and could be fully automated in future versions for clinical use. Therefore, it may be useful to begin assessing its predictive power for the important ability of open-set speech recognition. In Figure 6, control data from F-Fc (n=12) and F-RFc (n=12) obtained from the two groups of 6 subjects with the TTB masker were compared with open-set speech recognition from an earlier study, which used the same number of subjects (n=12) in the same two spatial conditions, and the same target sentences in the presence of the same two-talker masker (Freyman et al. 2007, left and middle panels of Fig. 1, “jskc” masker). Interpolation of current data to obtain points for comparison at common SNRs resulted in points that are exactly half way between the tested SNRs. The speech recognition measures are highly correlated in the positive direction using Pearson Correlation (y = 2.5097x − 123.59, R2 = 0.9101, p < 0.001). The linear regression line indicates that 75% correct on this same-different task occurred at SNRs where open-set performance is predicted to be around 65% correct. It should be noted that although there seems to be a strong correlation, the number of conditions and data set are small, and much further study is needed before extending these predictions beyond the limited data shown.

Fig. 6.

Group mean-percent correct scores for conventional open-set speech recognition (data from Freyman et al. 2007; n=12) plotted as a function of group mean-percent correct scores for the same-different task with the two control conditions F-RFc (closed circles) and F-Fc (open circles); (n=12). The same target sentences in the presence of the same two-talker masker were used in both sets of data. Interpolation of current data to obtain points for comparison at common SNRs resulted in points that are exactly half way between the tested SNRs.

Summary and Interpretation

In this study, listeners were asked to compare a sentence displayed visually on a computer monitor with the auditory presentation of an identical or slightly different partially masked nonsense sentence. The same-different discrimination task was easier when the visual display of the nonsense sentence preceded the masked auditory presentation than when it followed it, even in foil trials. The benefits of this type of priming were observed with a two-talker speech masker in both spatial and non-spatial conditions (Fig. 3a and Fig. 4), and both steady state and speech-modulated noise maskers (Fig. 3b and Fig. 3c).

The results suggest that priming is effective in improving speech perception in the presence of maskers thought to produce predominantly energetic masking to a degree comparable to those that include significant informational masking. Freyman et al. (2004), as well as others, could not see this finding with the methods used in those studies, where it is assumed that misperception of the last key word in the case of noise masking was due to insufficient audibility, a problem which was likely unresolved by priming the first two key words. Noise maskers are widely considered to produce only energetic masking for speech targets, and this was reinforced by the demonstration that perceived spatial separation created by the precedence effect did not lead to improvements in performance (Figs. 3b and 3c) as it did for the two-talker masker (Fig. 3a). There was also considerable benefit of priming with the two-talker babble in the spatial condition (Fig. 4), and this was presumably a condition that contains little residual informational masking.

Consistent with the overall percent correct data, the details of the effects of priming on different foil positions within the sentences were very similar for the masker that likely contained a significant informational component and those considered to produce mostly energetic masking. These position effects were far different from those resulting from the provision of target-masker spatial separation. The current interpretation is that perceived spatial separation released informational masking (in agreement with the interpretations in previous studies), while the priming benefit that can be attributed directly to anything beyond energetic masking for maskers that contain both types of masking is not evident. This account is perhaps difficult to reconcile with the subjective impression one has when listening, which is that in the presence of the speech masker the provision of the prime causes the target-masker complex to be perceptually reorganized rather dramatically, with the target moving to the perceptual foreground and masker moving to a more easily ignorable background. Further study on conditions in which informational masking is the dominant or exclusive form of masking appears warranted.

The above interpretation depends on the accuracy of the presumptions that broadband noise and the spatially-separated two-talker speech masker produced little informational masking. If these assumptions are incorrect then the attribution of the effect of priming in these conditions to release energetic masking would need to be reconsidered. While there is no direct evidence for this alternative view of noise masking that we are aware of, it cannot be explicitly ruled out by the current data.

The same-different task used for these experiments seems to hold promise as a measure of speech recognition when compared to conventional methods, demonstrated by a strong linear relationship between the current measure for the control condition and earlier open-set speech recognition data obtained with the same stimuli (Fig. 6). The test can be run automatically under computer control, can be administered to subjects or patients with impairments to speech production, and does not require accurate speech perception by the tester. Discovering whether performance on this test can reliably predict open-set speech recognition performance will require more research. Finally, as in the current experiment, the effect of priming could be determined in clinical patients by conducting the test in both orders of presentation (i.e., written sentence before and after the auditory sentence). This would be useful if future research establishes that improvements in the prime condition relate to a listener’s ability to benefit from context in a more general sense.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sarah F. Poissant for her comments on earlier versions of this manuscript, Sarma Vangala for programming these experiments, Neil Macmillan for consultation on signal detection theory, Amanda Lepine and April Teehan for assistance with data collection, and Ying-Yee Kong for her comments on earlier versions of this manuscript and for providing the processing algorithms for the noise maskers used in this study. This work was supported by NIDCD Grant No. 01625.

References

- Brungart DS, Simpson BD, Freyman RL. Precedence-based speech segregation in a virtual auditory environment. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118(5):3241–3251. doi: 10.1121/1.2082557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church BA, Schacter DL. Perceptual specificity of auditory priming: Implicit memory for voice intonation and fundamental frequency. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1994;20:521–533. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.20.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deese J, Kaufman RA. Serial effects in recall of unorganized and sequentially organized verbal material. J Exp Psychol. 1957;54(3):180–187. doi: 10.1037/h0040536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubno JR, Ahlstrom JB, Horwitz AR. Use of context by young and aged adults with normal hearing. J Acoust Soc Am. 2000;107(1):538–546. doi: 10.1121/1.428322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzatian P, Li L, Pichora-Fuller K, Schneider B. The effect of masker type and word-position on word recall and sentence understanding. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;123(5):3721. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzatian P, Li L, Pichora-Fuller K, Schneider B. The effect of priming on release from informational masking is equivalent for younger and older adults. Ear Hear. 2011;32(1):84–96. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181ee6b8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon M, Trehub SE, Schneider BA. Children’s use of semantic cues in degraded listening environments. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;111(5):2242–2249. doi: 10.1121/1.1466873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyman RL, Balakrishnan U, Helfer KS. Spatial release from informational masking in speech recognition. J Acoust Soc Am. 2001;109(5):2112–2122. doi: 10.1121/1.1354984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyman RL, Balakrishnan U, Helfer KS. Effect of number of masking talkers and auditory priming on informational masking in speech recognition. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115(5):2246–2256. doi: 10.1121/1.1689343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyman RL, Helfer KS, Balakrishnan U. Variability and uncertainty in masking by competing speech. J Acoust Soc Am. 2007;121(2):1040–1046. doi: 10.1121/1.2427117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyman RL, Helfer KS, McCall DD, Clifton RK. The role of perceived spatial separation in the unmasking of speech. J Acoust Soc Am. 1999;106(6):3578–3588. doi: 10.1121/1.428211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfer KS. Auditory and auditory-visual perception of clear and conversational speech. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1997;40:432–443. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4002.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfer KS, Freyman RL. Aging and speech-on-speech masking. Ear Hear. 2008;29(1):87–98. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31815d638b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James RC. Photograph of a dalmatian. In: Goldstein EB, editor. Sensation and perception. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1996. p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y-Y, Zeng F-G. Temporal and spectral cues in Mandarin tone recognition. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;120(5):2830–2840. doi: 10.1121/1.2346009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Daneman M, Qi JG, Schneider BA. Does the information content of an irrelevant source differentially affect spoken word recognition in younger and older adults? J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2004;30:1077–1091. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.30.6.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection Theory: A User’s Guide. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- Most T, Adi-Bensaid L. The influence of contextual information on the perception of speech by postlingually and prelingually profoundly hearing-impaired Hebrew-speaking adolescents and adults. Ear Hear. 2001;22(3):252–263. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock BB., Jr The serial position effect of free recall. J Exp Psychol. 1962;64(5):482–488. [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne GP, Ivey ES, Tolhurst GC. Hearing protector evaluation in an audiometric testing room. Sound Vib. 1983;17:20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nittrouer S, Boothroyd A. Context effects in phoneme and word recognition by young children and older adults. J Acoust Soc Am. 1990;87(6):2705–2715. doi: 10.1121/1.399061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilotti M, Bergman ET, Gallo DA, et al. Direct comparison of auditory implicit memory tests. Psychon Bull Rev. 2000;7(2):347–353. doi: 10.3758/bf03212992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakerd B, Aaronson NL, Hartmann WM. Release from speech-on-speech masking by adding a delayed masker at a different location. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;119(3):1597–1605. doi: 10.1121/1.2161438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankovic CM, Levy RM. Estimating articulation scores. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;102(6):3754–3761. doi: 10.1121/1.420138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Allbritton D, McKoon G. Bias in Auditory Priming. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1997;23(1):143–152. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.23.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, McKoon G. A counter model for implicit priming in perceptual word identification. Psychol Rev. 1997;104(2):319–343. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger HL., III Implicit memory: Retention without remembering. Am Psychol. 1990;45:1043–1056. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.9.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Church BA. Auditory priming: Implicit and explicit memory for words and voices. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1992;18:915–930. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.18.5.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Church BA, Treadwell J. Implicit memory in amnesic patients: Evidence for spared auditory priming. Psychol Science. 1994;5:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon S, Pichora-Fuller MK, Schneider BA. Priming and sentence context support listening to noise-vocoded speech by younger and older adults. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;123(1):489–499. doi: 10.1121/1.2783762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E, Schacter DL. Priming and human memory systems. Science. 1990;247:301–306. doi: 10.1126/science.2296719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach H, Newman EB, Rosenzweig MR. The precedence effect in sound localization. Am J Psychol. 1949;62:315–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Chen J, Huang Q, et al. The effect of voice cuing on releasing Chinese speech from informational masking. Speech Commun. 2007;49:892–904. [Google Scholar]