Abstract

We present series of head, neck extracranial non-vestibular schwannomas treated during 2-year period. All patients with head and neck schwannomas treated at our department from April 2007 to July 2009 were reviewed. There was female predominance (72%). The mean age at diagnosis was 38 years. All (100%) presented with a neck mass. Most common nerves of origin were the vagus and the cervical sympathetic chain. Treatment for all cases was complete excision with nerve preservation. Among all schwannoma patients, postoperative neural deficit occurred in four with partial to complete resolution in three. The follow-up period was 24 months. Non-vestibular extracranial head and neck schwannomas most frequently present as an innocuous longstanding unilateral parapharyngeal neck mass. Preoperative diagnosis may be aided by fine-needle cytology and magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomographic imaging. The mainstay of treatment is complete intracapsular excision preserving the nerve of origin.

Keywords: Schwannoma, Neurilemmoma, Extra vestibular

Introduction

Schwannomas, also known as neurilemmomas, neuromas, or neurinomas, are uncommon nerve sheath neoplasms that may originate from any peripheral, cranial or autonomic nerve of the body with the exception of the olfactory and optic nerve. Malignant change is unusual. Cervical vagal schwannomas are rare, slow-growing tumours usually reported to occur in patients between 30 and 50 years of age. There does not seem to be a sex-related predisposition.

Despite the fact that a large proportion of head and neck schwannoma studies is devoted to intracranial acoustic neuromas, the majority of head and neck schwannomas are non-vestibular and extracranial. Some 25–45% [1] of schwannomas are located in the head, and these often present as diagnostic and management challenges. Imaging plays a central role in diagnosing vagal nerve neoplasm and in particular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become the routine imaging study for these tumours. They are usually asymptomatic benign lesions and complete surgical resection is the treatment of choice.

Materials and Methods

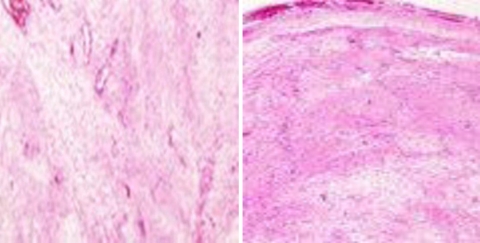

All patients with head and neck schwannomas treated at our department between April 2007 and July 2009 were reviewed from a single institution Maharaja Yeshwantrao Hospital, the largest tertiary hospital in Madhya Pradesh, India. Data collected included patient age, sex, race, presenting signs and symptoms, anatomical location of the tumour, tumour size, nerve of origin, diagnostic modality, surgical approach, intraoperative finding, histopathological finding, and outcome after treatment. The presence of characteristic Antoni A or B histologic patterns with or without S-100 stain was used to identify schwannomas. S-100 immunohistochemical staining is positive [1] in most Schwann cell-derived tumours. Grossly identified, schwannomas are well circumscribed encapsulated firm, grey myxoid masses attached to nerve but may have areas of cystic and xanthomatous change (Figs. 1, 2, and 3).

Fig. 1.

Histopathological examination typical of schwannomas

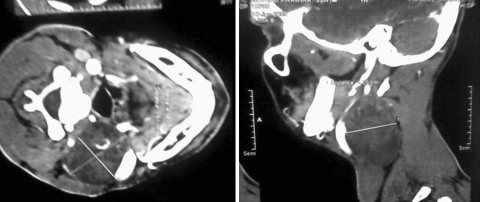

Fig. 2.

Showing resection of the schwannoma with preservation of the vagus

Fig. 3.

CT scan showing schwannoma

Results

Eight patients with head and neck schwannomas were identified. Our study set of schwannomas was necessarily extracranial non-vestibular and mainly non-trigeminal because the vestibular and trigeminal schwannoma patients usually receive tertiary treatment through either otolaryngology or neurosurgery.

The study population consisted of two males and six females, with a mean age of 38 years (range 10–64) and a median age of 33 years. Usual age of presentation is from 30 to 50 years except for two cases in extremes of age, one case being 64 year old and another being a paediatric case only 10 year old which is a rare occurrence. Each had a solitary head and neck schwannoma and none suffered from neurofibromatosis. All eight patients underwent preoperative computed tomography (CT) or MRI to facilitate diagnosis and delineate extent and related anatomy. All patients underwent surgical excision of the tumour. Table 1 shows the epidemiological data of the population, along with the presenting signs and symptoms, initial diagnosis, and diagnostic modality utilised.

Table 1.

Epidemiological characters, nerve of origin, investigations of the recorded patient in the case series

| Patient | Age/sex | History | Clinical diagnosis | Investigations | Nerve of origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 10 years/M | Right neck mass—since 8 years | Reactive lymphadenopathy | FNAC inconclusive IHC advised CT vagal schwannoma | Vagus |

| B | 30 years/F | left neck mass—since 8 months | Thyroid nodule | FNAC hgic aspirate CT thyroid cyst | Vagus |

| C | 40 years/F | Right neck mass—since 5 years | Level 2 lymph nodes | FNAC hgic aspirate CT vagal schwannoma | Vagus |

| D | 48 years/F | left neck mass—since 4 years | Carotid body tumor | CT metastatic lymphnode | Vagus |

| E | 50 years/F | Right neck mass—since 1 year | Right supraclavicular lymph node | MRI schwannoma | Accessory |

| F | 64 years/M | left neck mass—since 3 years | Carotid body tumor | FNAC schwannoma MRI schwannoma | Sympathetic chain |

| G | 32 years/F | Right neck mass—since 4 years | Level 3 lymph nodes | FNAC inflammatory lesion CT enlarged lymphnode | Sympathetic chain |

| H | 28 years/F | Right neck mass—since 2 years | Solitary thyroid nodule | FNAC? schwannoma CT schwannoma | Unknown |

A unilateral neck mass was reported in all (100%) patients making it the most common presentation of a schwannoma. Of these, 5(66%) had a neck mass that was right sided.

Out of all the cases, 3 (34%) were left-sided Schwannomas. In our case series the nerve of origin (Table 1) was identified in 7 (95%) of 8 patients. Of those identified, 4 were derived from the vagus nerve; 2, the cervical sympathetic chain; and 1, the accessory nerve (Table 2).

Table 2.

Post operative follow up and associated symptoms and recovery times

| Patient | Nerve of origin | Post operative symptoms | Follow up |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Vagus | Hoarseness and vocal cord paresis | Spontaneous recovery in 12 months |

| B | Vagus | Hoarseness | Lost in follow up with no complaints |

| E | Sympathetic chain | Horner’s syndrome and pain over Temporo- Mandibular joint and preauricular region | Spontaneous recovery in 12 months |

| G | Accessory | Wound paresthesias | Spontaneous recovery in 12 months |

In all cases, the tumour was completely resected surgically. The surgical approach varied depending on the preoperative presumptive diagnosis, location and size of the tumour, and surgeon preference.

Postoperative neural deficit was documented in 4 (50%) patients with spontaneous recovery in 3. In our case series, 2 out of 4 vagal schwannomas were associated with vocal cord palsy and voice hoarseness post operatively, cervical sympathetic chain with Horner’s syndrome. Notably, the patient who had a cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma excised developed postoperative ipsilateral chronic pain over the temporomandibular joint and preauricular region, probably from injury to the great auricular nerve. The case of accessory nerve schwannoma manifested postoperative deficit in the form of wound paresthesia.

None of the patients suffered wound infection, haematoma, or cerebrospinal fluid leak, which are possible characteristic sequelae reported in other series.

The patient follow-up period was of 24 months. All remained free of disease at last follow-up consultation. None of the schwannomas was malignant.

Discussion

Schwannomas are rare peripheral nerve tumours; about one-third occur in the head and neck region [1]. Clinically, they present as asymptomatic slow-growing lateral neck masses that can be palpated along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Pre-operative diagnosis of schwannoma is difficult because many vagal schwannomas do not present with neurological deficits and several differential diagnoses for tumour of the neck may be considered, including paraganglioma, branchial cleft cyst, malignant lymphoma, metastatic cervical lymphadenopathy [2]. Furthermore, due to their rarity, these tumours are often not even taken into consideration in the differential diagnosis.

When symptoms are present, hoarseness is the most common. Occasionally, a paroxysmal cough may be produced on palpating the mass. This is a clinical sign, unique to vagal schwannoma. Presence of this sign, associated with a mass located along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, should make clinicians suspicious of vagal nerve sheath tumours [1, 3–5].

The usefulness of FNAB is still controversial; the majority of Authors do not recommend open or needle biopsy for these masses [2]; in our case, a FNAB was performed before admission, by the physicians that first evaluated the patient, but it was inconclusive in 6 patients and only in 2 (25%) was a definitive cytological diagnosis of schwannoma made based on the diagnosis of characteristic Verocay bodies and by the presence of spindle cells. Histologically, it exhibits two main patterns—Antoni A and Antoni B. Antoni A tissue is represented by a tendency towards palisading of the nuclei about a central mass of cytoplasm (Verocay bodies). In contrast, Antoni B tissue is a loosely arranged stroma in which the fibers and cells form no distinctive pattern. A mixed picture of both types can exist. Other typical features include necrosis, hemorrhage and cystic degeneration. Malignant change in the nerve sheath tumors in the head and neck is very rare. The diagnostic accuracy of FNA depends strongly on the specimen quality and the experience of the cytopathologist.

Based on tumour location, morphology and even signal characteristics, the radiological diagnosis of schwannoma was suggested in 5 of 8 (63%) cases in which preoperative MRI and/or CT was performed. Three had MRI alone done; the remaining 5 received only CT scanning of the tumour. Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI are respectively useful in assessing bony and soft tissue involvement [5]. On CT scans, schwannomas appear well-covered, well-defined and fusiform; they show relatively homogeneous contrast enhancement with internal cystic change becoming more prominent as the tumour enlarges. This cystic change is associated with mucinous degeneration, haemorrhage, necrosis, and microcyst formation. Ultrasonic images of schwannoma are characterised by a round or elliptical cross-section with a clear border with the internal echo reflective of histology.

Patterns may be homogeneous to heterogeneous and cystic change may be seen, as was the case in one patient with a right supraclavicular schwannoma. Ultrasound has greater diagnostic utility when the diameter of the nerve of origin is large and it can be seen that the tumour is connected to the often well-delineated nerve [6, 7]. Even with MRI or CT scans, it was in some instances in our series difficult to distinguish adenopathy from schwannoma. The definitive diagnosis remains that which is derived from tissue.

There is general agreement concerning the great value of MRI in the pre-operative work-up as it is helpful in defining diagnosis and in evaluating the extent and the relationship of the tumour with the jugular vein and the carotid artery. The MRI appearance is considered quite typical and may lead to suspicion of the diagnosis pre-operatively as the cervical vagal neurinoma frequently appears as a well-circumscribed mass lying between the internal jugular vein and the carotid artery. As reported by Furukawa et al., MRI findings are also useful in providing a pre-operative estimation of the nerve of origin of the schwannomas and to differentiate pre-operatively between schwannoma of the vagus nerve and schwannoma of the cervical sympathetic chain. The vagal schwannomas, in fact, displace the internal jugular vein laterally and the carotid artery medially, whereas schwannomas from the cervical sympathetic chain displace both the carotid artery and jugular vein without separating them [8–12]. In our case, the criteria of Furukawa et al. [8] were present. MRI characteristics 6 of schwannomas include specific signs (split fat sign, fascicular sign, target sign) and signal patterns (i.e., isointense T1 signal relative to skeletal muscle; increased and slightly heterogeneous T2 signal).

MRI also finds application in evaluating schwannomas thought to be highly vascular or closely related to vasculature, with angiography used for cases requiring preoperative embolisation.

Treatment of vagal nerve tumours is complete surgical excision. At surgery, these tumours appear as yellowish- white, well-circumscribed masses. Dissection of the tumour from the vagus with preservation of the neural pathway should be the primary aim of surgical treatment for these tumours. There was no recurrence for all the cases after complete surgical removal. Most authors [3, 9] have recommended careful intracapsular excision of the tumour to minimize postoperative neural deficit. Microneurosurgery to facilitate intraoperative microscopic diagnosis of the schwannoma and achieve more superior nerve preservation has been described. This involves microscopic enucleation of the tumour after opening epineurium without disrupting nerve continuity. Even as all attempts are made to preserve the nerve of origin, structural preservation may not necessarily lead to preservation of its functional integrity—this was apparent among our patients with postoperative neural deficit.

The literature [5, 13] appears to be in favour of the concept of subtotal or near-total tumour resection for nonvestibular head and neck schwannomas in situations where tumour is extensive and complete tumour resection cannot be achieved without compromising neural integrity and causing significant morbidity from paralysis and sensory loss. While some reports say Incomplete treatment, such as open biopsy, should be avoided, since it makes definitive excision of the tumour much more difficult.

If it is impossible to find an adequate plane and is technically difficult to preserve the integrity of the nerve trunk, the involved segment may be resected and an end-to-end anastomosis performed using microsurgical techniques [3].

This type of procedure often results in definitive vocal cord paralysis. Malignant transformation is exceptional in solitary schwannomas and evidence suggests that subtotal resection may provide adequate disease control of non-vestibular head and neck schwannoma, although continued follow-up is mandated. In our series, within the period of follow up of 24 months no cases were recorded with recurrences.

Certainly, a conservative non-operative approach is a valid option for head and neck schwannomas if the diagnosis has been established and the patient is tolerating the tumour well without neurogenic deficit, mass effect or rapid progression. Surgery, however, remains definitive treatment.

References

- 1.Chang SC, Schi YM. Neurilemmoma of the vagus nerve: a case report and brief literature review. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:946–949. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198407000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colreavy MP, Lacy PD, Hughes J, Bouchier-Hayes D, Brennan P, O’Dwyer AJ, et al. Head and neck schwannomas—a 10-year review. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114:119–124. doi: 10.1258/0022215001905058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford LC, Cruz RM, Rumore GJ, Klein J. Cervical cystic schwannoma of the vagus nerve: diagnostic and surgical challenge. J Otolaryngol. 2003;32:61–63. doi: 10.2310/7070.2003.35400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujino K, Shinohara K, Aoki M, Hashimoto K, Omori K. Intracapsular enucleation of vagus nerve-originated tumours for preservation of neural function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:334–336. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.107889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilmer-Hill HS, Kline DG. Neurogenic tumours of the cervical vagus nerve: report of four cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:1498–1503. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200006000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaman FD, Kransdorf MJ, Menke DM. Schwannoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24:1477–1481. doi: 10.1148/rg.245045001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamazaki H, Kaneko A, Ota Y, Tsukinoki K. Schwannoma of the mental nerve: usefulness of preoperative imaging: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97:122–126. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(03)00462-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furukawa M, Furukawa MK, Katoh K, Tsukuda M. Differentiation between schwannoma of the vagus nerve and schwannoma of the cervical sympathetic chain by imaging diagnosis. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:1548–1552. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199612000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito DM, Glastonbury CM, El-Sayed I, Eisele DW. Parapharyngeal space schwannomas. Preoperative imaging determination of the nerve of origin. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:662–667. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.7.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green JD, Jr, Olsen KD, Santo LW, Scheithauer BW. Neoplasm of the vagus nerve. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:648–654. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198806000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leu YS, Chang KC. Extracranial head and neck schwannomas: a review of 8 years experience. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:435–437. doi: 10.1080/00016480260000157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park CS, Suh KW, Kim CK. Neurilemmomas of the cervical vagus nerve. Head Neck. 1991;15:439–441. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880130512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu R, Fagan P. Facial nerve schwannoma: surgical excision versus conservative management. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:1025–1029. doi: 10.1177/000348940111001106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]