Rituximab use in hematology and oncology practice has significantly and positively improved the clinical outcomes in patients with a wide variety of B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. However, hepatitis B virus reactivation related to rituximab use is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in oncology practice. This article focuses on the current evidence that supports these recently revised clinical recommendations along with a review of the risk factors for reactivation, suggested monitoring, and preventative interventions.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, Rituximab, Reactivation, Lymphoma, Viral hepatitis

Learning Objectives

After completing this course, the reader will be able to:

Perform screening for prior hepatitis B viral exposure in all patients with hematologic malignancies who will receive rituximab as part of their therapy.

Implement prophylactic antiviral therapy in patients who are positive for hepatitis B and who are being treated with rituximab.

Monitor serum viral load and clinical signs of hepatic injury for at least six months following the completion of rituximab treatment in patients who are hepatitis B-sAg positive.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com

Abstract

Rituximab use in hematology and oncology practice has significantly and positively improved the clinical outcomes in patients with a wide variety of B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. However, emerging data reveal that there is a risk of viral hepatitis B reactivation in some patients treated with rituximab. Many of these cases result in treatment delays, inferior oncologic outcomes, increased morbidity, and more rarely fulminant hepatic decompensation and death. Indeed, the rituximab package insert and many clinical practice guidelines have been modified to reflect these concerns. The true incidence and mechanism of reactivation are still being elucidated. This article focuses on the current evidence that supports these recently revised clinical recommendations along with a review of the risk factors for reactivation, suggested monitoring, and preventative interventions.

Introduction

Rituximab (Rituxan®; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) has transformed the management of malignant B-cell oncology and is increasingly being considered in nonmalignant lymphoproliferative and immune-mediated conditions. This chimeric murine/human monoclonal antibody targets the CD20+ antigen of the surface of normal and malignant B lymphocytes, which is present in up to 95% of B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL). Tumor cell killing is mediated through the activation of complement-dependent B-cell cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. Rituximab is FDA-approved for first-line treatment of diffuse large, B-cell, CD20+ positive NHL in combination with anthracycline-based regimens or CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) chemotherapy [1–3] and as first-line treatment of follicular, CD20+ positive, B-cell NHL in combination with CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone) chemotherapy [4]. Other indications include treatment for relapsed or refractory, low-grade, or follicular CD20+ positive, B-cell NHL [5–8] and treatment for stable low-grade CD20+, B-cell NHL following a partial or complete response to first-line treatment with CVP [9]. Rituximab is also FDA-approved for use in combination with methotrexate in moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis previously unresponsive to antitumor necrosis factor therapy [10]. Efficacy in other lymphocytic and immune mediated disorders is the source of ongoing investigation [11].

Rituximab is very well tolerated by the vast majority of patients. One quarter of patients receiving rituximab may experience fever, chills, infection, asthenia, and lymphopenia. Serious adverse reactions associated with rituximab are rare but include infusion reactions, mucocutaneous reactions, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and tumor lysis syndrome. A depletion of B-cells has been shown to occur within the first three doses and can last for up to 9 months following treatment. B-cell recovery begins around 6 months after treatment and levels may return to normal by 12 months [11]. Viral infections such as cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella zoster virus have been reported up to 1 year after discontinuation of therapy. Of particular note is the potential for reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in oncology patients, which may lead to an interruption of chemotherapy and pose increased treatment-related mortality [11, 12]. It is this latter complication that is the focus of this review.

Reactivation of Hepatitis B Virus

HBV is a DNA virus belonging to the Hepadnavirus family. It has been estimated to affect more than one third of the global population, comprised of up to 400 million chronic carriers of infection [12–16]. Infection can result in a variety of clinical conditions ranging from a transient, asymptomatic state to progressive jaundice and fulminant hepatic decompensation. Patients with underlying cirrhosis are at an increased risk for severe symptoms and mortality [12].

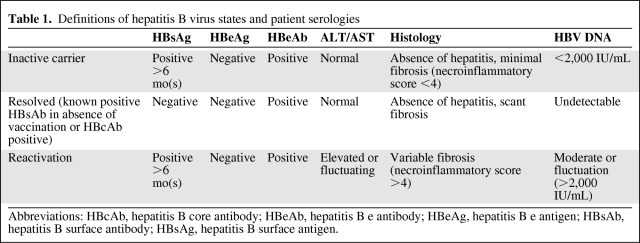

According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Chronic Hepatitis B Guidelines, reactivation of hepatitis B is defined as the reappearance of active necroinflammatory disease of the liver in a person known to have (1) an inactive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) carrier state (persistent HBV infection of the liver without significant, ongoing necroinflammatory disease) or (2) resolved hepatitis B (previous HBV infection without further virologic, biochemical, or histological evidence of active virus infection or disease) [17]. Thus, HBV reactivation can occur in both inactive carriers as well as those with resolved HBV infection. However, viral reactivation rates appear highest in those with HBsAg positive serologies, especially those with active HBV replication (HBV DNA positive in serum). Those with the lowest risk of reactivation are patients positive for hepatitis core antibody (HBcAb) with previous exposure and no evidence of a chronic carrier state (HBsAg negative) [17, 18]. Table 1 summarizes HBV reactivation definitions and serologies.

Table 1.

Definitions of hepatitis B virus states and patient serologies

Abbreviations: HBcAb, hepatitis B core antibody; HBeAb, hepatitis B e antibody; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAb, hepatitis B surface antibody; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

In 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration notified healthcare professionals about reports of fulminant HBV, hepatic failure, and death in patients with hematologic malignancies receiving rituximab [11]. Reactivation of HBV due to the immunosuppressive actions of rituximab has been reported in both HBsAg positive carriers and those with chronic HBV infection [13]. As a result of increasing clinical attention to this matter and recent reports of HBV reactivation, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has recently issued a Provisional Clinical Opinion on HBV screening in patients receiving treatment of malignant diseases [19].

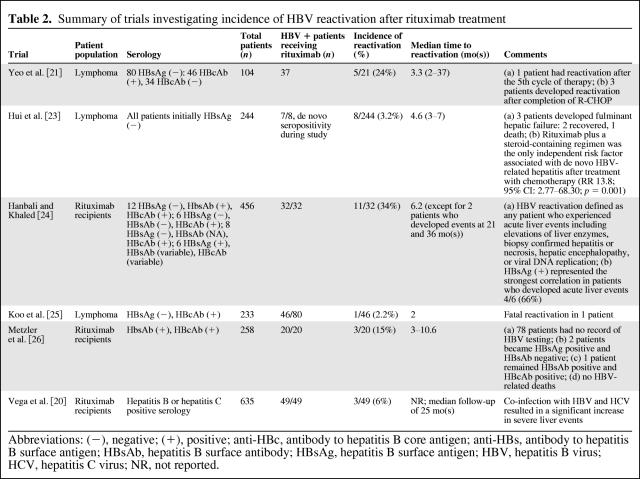

The possible relationship between rituximab and hepatitis B may be explained by the depletion of B cells, which serve critical roles in both T-cell and antibody-mediated immunity in HBV infection [12]. Reactivation of HBV typically occurs between 4 months after initiation of and 1 month after completion of rituximab therapy [11]. The overall incidence of reactivation with use of rituximab is unclear, but ranges from 2% to 35% of patients (Table 2) [20–26]. There is a paucity of published data on hepatitis B reactivation in patients receiving rituximab for nonmalignancy indications, such as for the treatment of graft versus host disease or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Table 2.

Summary of trials investigating incidence of HBV reactivation after rituximab treatment

Abbreviations: (−), negative; (+), positive; anti-HBc, antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; anti-HBs, antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen; HBsAb, hepatitis B surface antibody; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; NR, not reported.

The addition of rituximab to CHOP (R-CHOP) chemotherapy in diffuse large B-cell NHL (DLBCL) has demonstrated an increase in response rate, event-free, and overall survival [27]. This has become a well-established standard of care [28]. However, the addition of rituximab has also been shown to increase the risk of HBV reactivation both in inactive carriers and those with resolved HBV. Yeo et al. [21] examined the risk of HBV reactivation in a prospective study where newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell, CD20+ positive NHL patients were observed for HBV reactivation. This was defined as an increase in HBV DNA levels of tenfold or more compared to baseline or an absolute increase of HBV DNA levels >1,000 × 106 genomic equivalents per mL in absence of systemic infection with alanine transaminase (ALT) elevation during and for 6 months after anticancer therapy. Of the entire cohort of diagnosed CD20 positive DLBCL, 80 of 104 patients were negative for HBsAg at baseline. However, 46 of these HBsAg negative patients were positive for the antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc), indicating resolved prior HBV infection. Reactivation of hepatitis B occurred in 5 of 21 (24%) of these patients when treated with R-CHOP for 5–8 cycles. None of the remaining 25 (anti-HBc positive) patients treated with CHOP alone developed reactivation following treatment. Of the 5 patients who developed HBV reactivation, 3 patients had resolution of hepatitis with antiviral medication and 1 patient died of hepatic failure despite receiving antiviral medication, whereas another patient had spontaneous resolution of HBV without antiviral medication. Time to reactivation from the last chemotherapy cycle ranged from 19 to 170 days. Peak ALT and peak HBV DNA levels ranged from 362 to 2,110 U/L and from 4,820 to 231,598 copies/mcL, respectively [21]. Vega and colleagues showed that 21 out of 49 (43%) patients with a positive hepatitis serology (HBsAb positive/HBcAb positive, HBcAb positive, or HBsAg positive) treated with rituximab developed liver events (defined as elevation of liver transaminases > 2 times the upper normal limit, new or worsening signs of cirrhosis, necrosis of the liver, and death secondary to liver failure viral reactivation). Of the 27 HBV positive patients, 11% developed viral reactivation resulting in death secondary to liver failure [20]. In a review of 97 cases of HBV reactivation during or after chemotherapy, 9 of 81 (11%) lymphoma patients had received rituximab as part of their therapy [13].

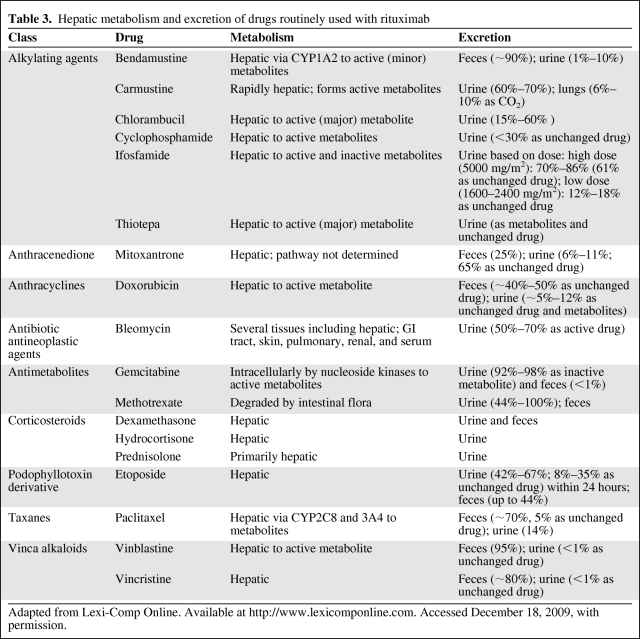

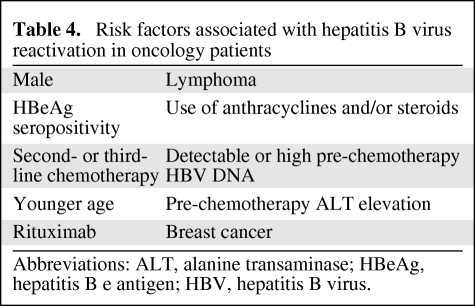

The mortality rate associated with viral reactivation has ranged from 4% to 60% [13]. Most deaths occur primarily because of acute liver failure [15]. Morbidity may be underestimated and falsely attributed to systemic chemotherapy. Liver dysfunction from HBV reactivation may result in increased systemic toxicity of chemotherapy agents that are hepatically metabolized and excreted (Table 3) [29]. Diagnostic parameters have not been established for HBV reactivation nor has there been specific grading of the associated hepatic decompensation [30]. Clinical signs and symptoms related to HBV reactivation may be subtle. A sudden increase in aminotransferase (ALT >5 times the upper limit of normal or >3 times above baseline) may be indicative of reactivation (i.e., hepatic flare), but can be seen in a variety of conditions related and unrelated to the oncologist's purview. Serum viral load increases about 2 to 3 weeks before ALT levels rise. Thus, rising viral load levels may serve as an important monitoring parameter prior to development of clinical sequelae. However, viral DNA levels may be declining or be undetectable when hepatic flare is clinically apparent. Hepatic flares may also be associated with an abnormal serum bilirubin, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, and prothrombin time, an increase in serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti-HBc and alpha fetoprotein levels, and encephalopathy [31, 32]. In addition to rituximab use, risk factors for HBV reactivation in oncology patients include male sex, use of anthracyclines, corticosteroid treatment, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seropositivity, and pre-existing abnormalities in liver function tests (Table 4) [12]. Hepatic flare can consequently lead to interruptions in delivering curative chemotherapy, lasting as long as 100 days [33]. Such delays in chemotherapy may result in a decreased disease-free and overall survival [15]. Even newly approved antineoplastic agents that target CD20+ lymphocytes including ofatumumab (Arzerra®, FDA approved October 2009; GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC) carry warnings about HBV reactivation and recommend screening patients prior to use [34].

Table 3.

Hepatic metabolism and excretion of drugs routinely used with rituximab

Adapted from Lexi-Comp Online. Available at http://www.lexicomponline.com. Accessed December 18, 2009, with permission.

Table 4.

Risk factors associated with hepatitis B virus reactivation in oncology patients

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Antiviral Prophylaxis

The use of antiviral medication to reduce viral replication and to prevent progression to worsening hepatitis has been extensively studied in the nononcology patient population. Lamivudine (Epivir®, Epivir-HBV®; GlaxoSmithKline), an oral nucleoside analogue, has been shown to reduce HBV viral load and improve liver injury in patients with chronic HBV [13–15]. Epivir® is FDA-approved for the treatment of HIV-1 infection as part of a multidrug regimen with at least three antiretroviral agents and is dosed to treat HIV-1 and not HBV [35–38]. Epivir-HBV® is FDA-approved for the treatment of chronic HBV associated with evidence of viral replication and active liver inflammation [39–42].

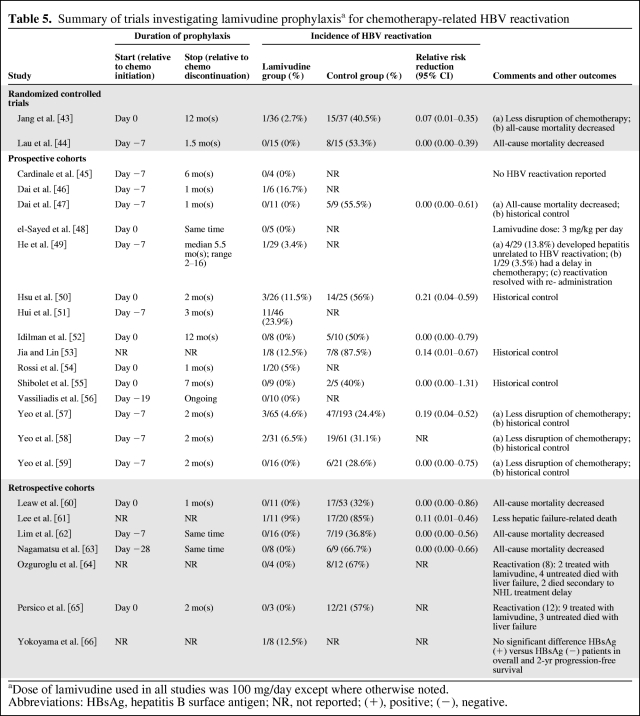

Lamivudine has been extensively studied as prophylaxis in the prevention of HBV reactivation during chemotherapy in HBsAg positive patients (Table 5) [14, 15, 43–66]. Loomba and colleagues published a systematic review of 14 trials (total of 275 patients) showing that lamivudine use significantly reduces the risk for both HBV reactivation and HBV-related hepatitis by nearly 80%. No patient with HBV reactivation died due to hepatic failure in the lamivudine prophylaxis arm in any of the studies included in this review. Control groups showed a higher disruption of chemotherapy and an increased rate of cancer-related and all-cause mortality [14]. Another review of 10 prospective trials, which included 5 studies not analyzed in the earlier review, showed a lower rate of hepatitis among subjects receiving lamivudine (16 of 173, 9.2%) compared with subjects not receiving lamivudine (63 of 116, 54%). Of patients receiving prophylaxis, 8.7% (15 of 173) developed HBV reactivation compared to 37% (43 of 116) without prophylaxis. Statistical significance and risk reduction were not assessed in this second review; however, none of the trials reported discontinuation of chemotherapy or withdrawal due to lamivudine toxicity [15]. Both reviews included studies with mostly inactive carriers (patients with HBsAg seropositivity and the highest risk of reactivation).

Table 5.

Summary of trials investigating lamivudine prophylaxisa for chemotherapy-related HBV reactivation

aDose of lamivudine used in all studies was 100 mg/day except where otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; NR, not reported; (+), positive; (−), negative.

Lamivudine is typically very well tolerated, although it can be associated with headache, nausea, malaise, fatigue, nasal signs and symptoms, diarrhea, and cough. Serious adverse reactions are rare and include lactic acidosis, severe hepatomegaly with steatosis, and pancreatitis. There have also been reports of severe acute exacerbations of hepatitis B and hepatic decompensation in patients co-infected with HIV-1 and hepatitis C, likely due to the development of HBV drug resistance [67]. The incidence of resistance to lamivudine can be as high as 20% after the first year of administration in patients with active HBV replication due to a mutation in the tyrosine-methionine-aspartate-aspartate motif of the HBV DNA polymerase gene (YMDD mutation) [16, 68, 69]. The development of drug resistance may be particularly relevant for patients who are likely cured from their NHL or other lymphoproliferative condition and have long-term needs for viral suppression due to active HBV infection.

Clinical Recommendations

In July 2009, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) NHL Guidelines were updated to include recommendations on rituximab-associated viral reactivation. Routine serologic testing for prior HBV exposure via surface antibody/antigen and core antibody/antigen is now recommended for patients with B-cell NHL. In addition, whereas a recent Provisional Clinical Opinion by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) found that there was not enough evidence to determine the benefits of routine screening for chronic HBV infection in cancer patients about to undergo cytotoxic chemotherapy, there are consistent recommendations that screening should be considered in those at high risk for HBV reactivation, particularly those patients who will receive rituximab as part of their therapy [19]. Known HBV carriers should be monitored closely for viral reactivation via serial serum viral loads during therapy and for at least 6 months following completion [28]. According to the clinical guideline recommendations, antiviral therapy should be considered as prophylaxis when treating HBV positive patients with rituximab [28, 70].

Unfortunately, there are few specific recommendations for the optimal dose and duration of prophylaxis at this time. The majority of relevant studies administered 100 mg of lamivudine by mouth daily until 6 months after the completion of chemotherapy. Lamivudine use during and for 6 months after completion of chemotherapy has also been recommended in recent guidelines published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases [14]. A longer duration of prophylaxis may be necessary in patients with higher initial levels of HBV DNA or those on maintenance rituximab [12]. Furthermore, HBV reactivation may increase following the withdrawal of lamivudine prophylaxis [15]. Due to the high risk of developing resistance to lamivudine with long-term therapy, other antiviral drugs should be considered in those patients who will require suppressive therapy beyond chemotherapy prophylaxis. Alternative antiviral agents like entecavir (Baraclude®; E.R. Squibb & Sons, L.L.C., New Brunswick, NJ), adefovir dipivoxil (Hepsera®; Gilead Sciences, Inc., Foster City, CA), and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Gilead Sciences, Inc.) may ultimately be preferred due to increased antiviral potency and decreased rates of current drug resistance [12]. Ongoing studies will help to validate these recommendations and resolve issues related to the heterogeneity of patient populations (i.e., inactive carriers versus resolved HBV infection), variable initiation, duration and follow-up of treatment, comparison with other antiviral agents, and comparison between hematologic, lymphoma, and nononcologic rituximab use.

Conclusions

HBV reactivation related to rituximab use is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in oncology practice. Serologic screening for prior HBV exposure or active infection should be performed prior to rituximab use in patients with hematologic malignancies. Antiviral prophylaxis should be started before chemotherapy and continued for at least 6 months following completion of all treatment for patients who are at high risk with HBsAg seropositivity and low HBV DNA <2,000 IU/mL. Evidence to support prophylaxis in patients with resolved HBV infection is limited. Lamivudine can be used if the duration of treatment is <12 months, whereas alternative antiviral agents (tenofovir or entecavir) may be preferred if anticipated treatment may last longer than 12 months. Prophylaxis should be continued until treatment endpoints are reached for reactivation of hepatitis B in patients with HBV DNA >2,000 IU/mL (Table 1) [17–19, 28]. Serum viral load should be monitored in those who are HBsAg positive, as well as close clinical monitoring for potential hepatic injury. Consultation with hepatology or infectious disease colleagues should also be considered, especially in those with active viral replication. If HBV reactivation of hepatitis B occurs, rituximab and any concomitant chemotherapy should be discontinued [28]. Although HBV reactivation may be self-limited with supportive care, antiviral therapy should be initiated as soon as possible (if not already used as prophylaxis) to prevent rapid progression to hepatic decompensation. Further clinical investigation is needed to answer many clinical questions including determining the optimal dose and duration of prophylaxis and establishing the safety of resuming rituximab after prior HBV reactivation.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Thomas J. George, Kourtney LaPlant, Jeryl Villadolid

Provision of study material or patients: Thomas J. George, Kourtney LaPlant, Jeryl Villadolid

Collection and/or assembly of data: Thomas J. George, Kourtney LaPlant, Jeryl Villadolid

Data analysis and interpretation: Thomas J. George, Kourtney LaPlant, Jeryl Villadolid

Manuscript writing: Thomas J. George, Merry Jennifer Markham, David R.

Nelson, Kourtney LaPlant, Jeryl Villadolid

Final approval of manuscript: Thomas J. George

References

- 1.Coiffier B, Feugier P, Mounier N, et al. Long-term results of the GELA study comparing R-CHOP and CHOP chemotherapy in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma show good survival in poor-risk patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl 18S):443s. Abstract 8009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, et al. Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3121–3127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Osterborg A, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(5):379–391. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus R, Imrie K, Catalano J, et al. Rituximab plus CVP improves survival in previously untreated patients with advanced follicular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Paper presented at: American Society of Hematology 48th Annual Meeting and Exposition; December 9–12, 2006; Orlando, FL. Abstract 481. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis TA, Grillo-Lopez AJ, White CA, et al. Rituximab anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: safety and efficacy of re-treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3135–3143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin P, Grillo-Lopez AJ, Link BK, et al. Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2825–2833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piro LD, White CA, Grillo-Lopez AJ, et al. Extended Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) therapy for relapsed or refractory low-grade or follicular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:655–661. doi: 10.1023/a:1008389119525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis TA, White CA, Grillo-Lopez AJ, et al. Single-agent monoclonal antibody efficacy in bulky non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: results of a phase II trial of rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(6):1851–1857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochster HS, Weller E, Ryan T, et al. Results of E1496: a phase III trial of CVP with or without maintenance rituximab in advanced indolent lymphoma (NHL) J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(suppl) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1561. Abstract 6502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):2793–2806. doi: 10.1002/art.22025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rituximab Package Insert. South San Francisco, CA: Biogen Idec, Inc. and Genentech, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeo W, Johnson PJ. Diagnosis, prevention and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation during anticancer therapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:209–220. doi: 10.1002/hep.21051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coiffier B. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer treatment: role of lamivudine prophylaxis. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:548–552. doi: 10.1080/07357900600815232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loomba R, Rowley A, Wesley R, et al. Systematic review: the effect of preventive lamivudine on hepatitis B reactivation during chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:519–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-7-200804010-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohrt HE, Ouyang DL, Keeffe EB. Systematic review: lamivudine prophylaxis for chemotherapy induced reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1003–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi G. Prophylaxis with lamivudine of hepatitis B virus reactivation in chronic HbsAg carriers with hemato- oncological neoplasias treated with chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:759–766. doi: 10.1080/104281903100006351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han ShB, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1315–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Artz AS, Somerfiled MR, Feld JJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion: Chronic hepatitis B virus infection screening in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy for treatment of malignant disease. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jun 1; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.0673. [Epub ahead of Print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vega J, Khalife M, Hanbali A, et al. Incidence of liver events in patients with hepatitis B and C treated with rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl) Abstract 8558. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NWY, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:605–611. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Rituximab: possible association with hepatitis B reactivation. WHO Pharm Newsletter. 2004;(5):5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hui CK, Cheung WW, Zhang HY, et al. Kinetics and risk of de novo hepatitis B infection in HBsAg-negative patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:59–68. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanbali A, Khaled Y. Incidence of hepatitis B reactivation following rituximab therapy. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(3):195. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koo YX, Tan DSW, Tan BH, et al. Correspondence: Risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients who are hepatitis B surface antigen negative/antibody to hepatitis B core antigen positive and the role of routine antiviral prophylaxis. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2570–2571. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metzler F, Mederacke I, Manns MP, et al. Rituximab leads to reactivation of hepatitis B in individuals with resolved infection. Hepatology. 2008;48:685A. AASLD Abstract 848. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Brière J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zelenetz AD, Abramson JS, Advani RH, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:288–334. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lexi-Comp. Lexi-Comp Online. [Accessed December 18, 2009]. Available at http://www.lexicomponline.com.

- 30.DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHHS. Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 3.0. Publish Date August 9, 2006. Available at http://ctep.cancer.gov.

- 31.Lok AS, Lai CL, Wu PC, et al. Spontaneous hepatitis B e antigen to antibody seroconversion and reversion in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1987;92(6):1839–1843. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90613-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lok AS, Lai CL. alpha-Fetoprotein monitoring in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: role in the early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1989;9:110. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silvestri F, Ermacora A, Sperotto A, et al. Lamivudine allows completion of chemotherapy in lymphoma patients with hepatitis B reactivation. Br J Haematol. 2000;108:394–396. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arzerra® Package Insert. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; [Accessed January 24, 2009]. Available at: http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_arzerra.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dore GJ, Cooper DA, Barrett C. Dual efficacy of lamivudine treatment in human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis B virus coinfected persons in a randomized, controlled study (CAESAR) J Infect Dis. 1999;180(3):607–613. doi: 10.1086/314942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeJesus E, McCarty D, Farthing CF, et al. Once-daily versus twice-daily lamivudine, in combination with zidovudine and efavirenz, for the treatment of antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV infection: a randomized equivalence trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(3):411–418. doi: 10.1086/422143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crémieux AC, et al. A comparison of the steady-state pharmacokinetics and safety of abacavir, lamivudine, and zidovudine taken as a triple combination tablet and as abacavir plus lamivudine-zidovudine double combination tablet by HIV-1 infected adults. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(4):424–430. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.5.424.34497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKinney RE, Jr, Johnson GM, Stanley K, et al. A randomized study of combined zidovudine-lamivudine versus didanosine monotherapy in children with symptomatic therapy-naive HIV-1 infection. J Pediatr. 1998;133(4):500–508. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Wright TL, et al. Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(17):1256–1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai CL, Chien RN, Leung NWY, et al. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. New Engl J Med. 1998;339:61–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiff ER, Dienstag JL, Karayalcin S, et al. Lamivudine and 24 weeks of lamivudine/interferon combination therapy for hepatitis B e antigen positive chronic hepatitis B in interferon nonresponders. J Hepatol. 2003;38(6):818–826. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jonas MM, Kelley DA, Mizerski J, et al. Clinical trial of lamivudine in children with chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1706–1713. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang JW, Choi JY, Bae SH, et al. A randomized controlled study preemptive lamivudine in patients receiving transarterial chemo-lipiodolization. Hepatology. 2006;43:233–240. doi: 10.1002/hep.21024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lau GK, Yiu HH, Fong DY, et al. Early is superior to deferred preemptive lamivudine therapy for hepatitis B patients undergoing chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1742–1749. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cardinale G, Merenda A, Pagliaro M, et al. Possible efficacy of lamivudine prophylaxis to prevent hepatitis B virus reactivation due to rituximab regimens in hepatitis B virus carriers with B cell lymphoprolipherative malignancies. Haematologica. 2008;93:S103. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dai MS, Wu PF, Lu JJ, et al. Preemptive use of lamivudine in breast cancer patients carrying hepatitis B virus undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:191–196. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0549-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dai MS, Wu PF, Shyu RY, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in breast cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy and the role of preemptive lamivudine administration. Liver Int. 2004;24:540–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.el-Sayed MH, Shanab G, Karim AM, et al. Lamivudine facilitates optimal chemotherapy in hepatitis B virus infected children with hematological malignancies: a preliminary report. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;21:145–156. doi: 10.1080/08880010490273019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He Y-F, Li Y-H, Wang F-H, et al. The effectiveness of lamivudine in preventing hepatitis B viral reactivation in rituximab-containing regimen for lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:481–485. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hsu C, Sur IJ, Hwang WS, et al. A prospective comparative study of prophylactic or therapeutic use of lamivudine for chemotherapy-associated hepatitis B (HBV) reactivation in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:S297. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hui CK, Cheung WW, Au WY, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation after withdrawal of pre-emptive lamivudine in patients with haematological malignancy on completion of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gut. 2005;54:1597–1603. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.070763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Idilman R, Arat M, Soydan E, et al. Lamivudine prophylaxis for prevention of chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B virus carriers with malignancies. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:141–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jia J, Lin F. Lamivudine therapy for prevention of chemotherapy-induced reactivation of hepatitis B virus. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2004;12:628–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rossi G, Pelizzari A, Motta M, et al. Primary prophylaxis with lamivudine of hepatitis B virus reactivation in chronic HbsAg carriers with lymphoid malignancies treated with chemotherapy. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:58–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shibolet O, Ilan Y, Gillis S, et al. Lamivudine therapy for prevention of immunosuppressive-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B surface antigen carriers. Blood. 2002;100:391–396. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vassiliadis T, Garipidou V, Tziomalos K, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B reactivation with lamivudine in hepatitis B virus carriers with hematologic malignancies treated with chemotherapy - a prospective case series. Am J Hematol. 2005;80:197–203. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeo W, Chan PK, Ho WM, et al. Lamivudine for the prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B s-antigen seropositive cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:927–934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yeo W, Ho WM, Hui P, et al. Use of lamivudine to prevent hepatitis B virus reactivation during chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;88:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-0725-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yeo W, Hui EP, Chan AT, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma with lamivudine. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28:379–384. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000159554.97885.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leaw SJ, Yen CJ, Huang WT, et al. Preemptive use of interferon or lamivudine for hepatitis B reactivation in patients with aggressive lymphoma receiving chemotherapy. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:270–275. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0825-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee GW, Ryu MH, Lee JL, et al. The prophylactic use of lamivudine can maintain dose-intensity of adriamycin in hepatitis-B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma who receive cytotoxic chemotherapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:849–854. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.6.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lim LL, Wai CT, Lee YM, et al. Prophylactic lamivudine prevents hepatitis B reactivation in chemotherapy patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1939–1944. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagamatsu H, Itano S, Nagaoka S, et al. Prophylactic lamivudine administration prevents exacerbation of liver damage in HB e antigen positive patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transhepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2369–2375. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ozguroglu M, Bilici A, Turna H, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B infection with cytotoxic therapy in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Med Oncol. 2004;21:67–72. doi: 10.1385/MO:21:1:67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Persico M, De Marino F, Russo GD, et al. Efficacy of lamivudine to prevent hepatitis reactivation in hepatitis B virus-infected patients treated for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2002;99:724–725. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yokoyama M, Ennishi D, Takeuchi K, et al. Lamivudine prophylaxis is effective for inhibition of hepatitis B viral reactivation in patients with diffuse large b-cell lymphoma undergoing R-CHOP like therapy. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(suppl 4):iv141. ICML Abstract 140. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lamivudine Package Insert. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ziakas P, Karsaliakos P, Mylonakis E. Effect of prophylactic lamivudine for chemotherapy-associated hepatitis B reactivation in lymphoma: a meta-analysis of published clinical trials and a decision tree addressing prolong prophylaxis and maintenance. Haematologica. 2009;94:998–1004. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.005819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simpson ND, Simpson PW, Ahmed AM, et al. Prophylaxis against chemotherapy-induced reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection with lamivudine. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:68–71. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200307000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sandherr M, Einsele H, Hebart H, et al. Antiviral prophylaxis in patients with haematological malignancies and solid tumours: Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society for Hematology and Oncology (DGHO) Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1051–1059. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]