This study identifies potential prognostic factors for survival in HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma patients who have undergone chemotherapy and describes their clinicopathological characteristics.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, Plasmablastic lymphoma, PBL, Prognostic factors

Abstract

Background.

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma commonly seen in the oral cavity of HIV-infected individuals. PBL has a poor prognosis, but prognostic factors in patients who have received chemotherapy have not been adequately evaluated.

Methods.

An extensive literature search rendered 248 cases of PBL, from which 157 were HIV+. Seventy cases with HIV-associated PBL that received chemotherapy were identified. Whenever possible, authors of the original reports were contacted to complete clinicopathological data. Univariate analyses were performed calculating Kaplan–Meier estimates and compared using the log-rank test.

Results.

The mean age was 39 years, with a male predominance. The mean CD4+ count was 165 cells/mm3. Advanced clinical stage was seen in 51% and extraoral involvement was seen in 43% of the cases. The expression levels of CD20 and Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA were 13% and 86%, respectively. The overall survival duration was 14 months. In a univariate analysis, early clinical stage and a complete response to chemotherapy were associated with longer survival. There was no apparent difference in survival with regimens more intensive than cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP).

Conclusions.

Patients with HIV-associated PBL have a poor prognosis. Prognosis is strongly associated with achieving a complete clinical response to CHOP or CHOP-like chemotherapy. The role of more intensive regimens is currently unclear. Further research is needed to improve responses using novel therapeutic agents and strategies.

Introduction

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a distinct variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and is strongly associated with HIV infection. PBL was initially described in 1997, arising most commonly in the oropharyngeal area of HIV-infected individuals [1]. Pathologically, PBL lacks expression of CD20, but because of its plasmacytic differentiation, expresses plasma cell markers such as CD38, CD138, or MUM1 (multiple myeloma oncogene 1). The clinical course of PBL is characteristically aggressive, with a reported median overall survival (OS) time of 15 months [2]. However, spontaneous regression with antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been reported [3–5], as well as prolonged and durable responses to chemotherapy [6–10].

Several prognostic factors have been identified in HIV-associated lymphomas; these include the International Prognostic Index (IPI) score [11] and CD4+ cell count [12], among others. Data on prognostic factors in PBL are lacking and these analyses are unlikely to be performed prospectively given the rarity of this malignancy, which accounts for <2% of all HIV-associated lymphoma cases [13]. The identification of prognostic factors in this population may allow a better understanding of the biology of this disease.

The principal objective of this study was to identify, from a thorough literature search, potential prognostic factors for survival in HIV-associated PBL patients who have undergone chemotherapy. A secondary objective was to describe their clinicopathological characteristics.

Methods

Search

An extensive literature search was undertaken using Pubmed/MEDLINE from January 1997 through September 2009. The search key was “plasmablastic lymphoma.” Our search included letters to the editor, case reports, and case series in all languages for which relevant clinicopathological information was available; the minimum criteria for inclusion were a pathological diagnosis of PBL according to the World Health Organization classification, age, sex, Ann Arbor clinical stage, chemotherapy received, response to chemotherapy, final outcome, and OS in months. Patients who did not fulfill all the minimum criteria, patients with a negative or unknown HIV status and patients who experienced a complete remission (CR) without ever receiving chemotherapy were excluded.

Data Gathering

Additional clinical data included CD4+ cell count, use of ART, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, sites of involvement (oral versus extraoral), bone marrow involvement, presence of B symptoms, and cause of death. Additional pathological data included immunohistochemical expression of CD20, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded RNA (EBER) [14] and Ki67, and cytogenetic abnormalities. Attempts to contact the authors of the original papers were done, whenever necessary, in order to obtain additional data. Approximately 40% of the authors were contacted by e-mail, with a response rate of 30%.

Statistical Analysis

Clinicopathological variables were dichotomized to facilitate analysis and are presented using descriptive methods. The OS time was defined as the time, in months, elapsed between the date of diagnosis and the date of death or last follow-up. The χ2 test was used to evaluate the association between the clinicopathological variables and response to chemotherapy and final outcome. Univariate analyses were done using Kaplan–Meier survival estimates, which were compared using the log-rank test. p-values < .004 were considered statistically significant, according to a Bonferroni correction for multiple observations. Calculations and graphs were obtained using MedCalc statistical software (Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Search Results

Our initial search resulted in 116 articles. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 33 articles were deemed not eligible because they were reviews, editorials, or laboratory experiments; 83 articles were selected for full-text retrieval. In total, 248 cases were extracted, from which 157 were HIV+. After excluding cases that did not meet our minimum inclusion criteria, 70 cases were deemed appropriate for this study. Cases originated from several countries, including the U.S., Canada, Germany, Italy, Spain, Greece, The Netherlands, India, Japan, Argentina, and Australia.

Clinicopathological Characteristics

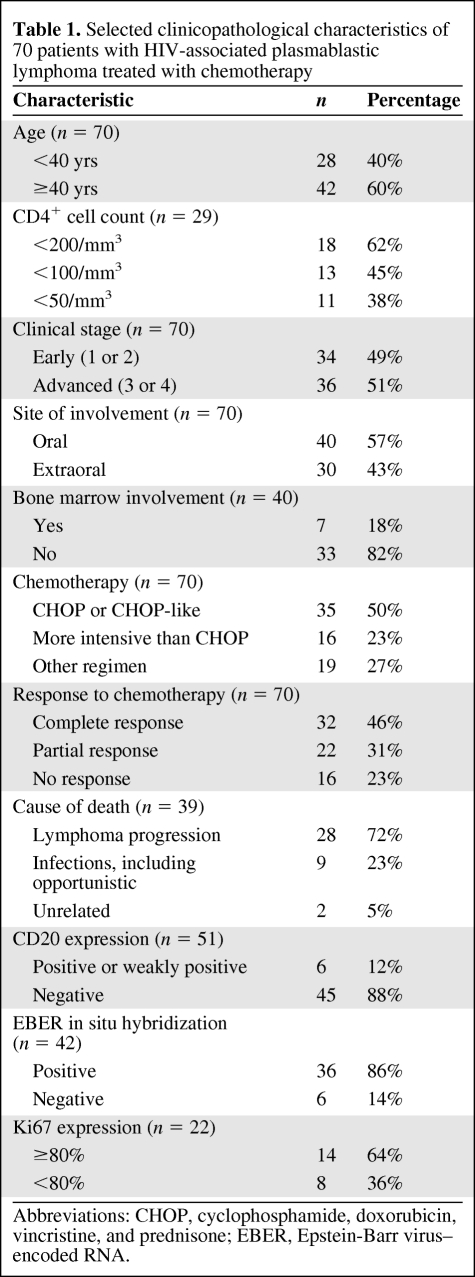

The main characteristics of HIV-associated PBL can be seen in Table 1. The median age at presentation was 38.8 years (range, 3–60 years). The male-to-female ratio was 4:1 (56 male and 14 female cases). In regard to HIV-related characteristics, the mean CD4+ cell count was 165 cells/mm3 (range, 3–484 cells/mm3), and 37% of cases received ART. Among the lymphoma-related clinical characteristics, performance status and LDH level were seldom reported (14% of the time in both cases); advanced clinical stage (3 and 4) was seen in 51% of the patients. Fifty-seven percent of cases presented with oral involvement, 18% presented with bone marrow involvement, and 37% presented with B symptoms. The overall response rate (ORR) to chemotherapy was 77% (CR, 46%; partial response [PR], 31%), with 57% of the patients deceased at the time of publication of their respective report. The most common cause of death was lymphoma progression (72%). Within the pathological features, CD20 was expressed in 13% of patients, EBER was positive in 86% of patients, and Ki67 expression ≥80% was seen in 64% of the cases. Of note, MYC/IgH rearrangement was reported in five patients. In regard to chemotherapy, 50% of the patients were treated with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) or CHOP-like regimens, 23% were treated with regimens more intensive than CHOP, such as the EPOCH, HyperCVAD, and CODOX-M/IVAC regimens, and 27% received other therapies or unspecified regimens; 19% received radiotherapy and 10% received intrathecal methotrexate.

Table 1.

Selected clinicopathological characteristics of 70 patients with HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma treated with chemotherapy

Abbreviations: CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; EBER, Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA.

Survival Analysis

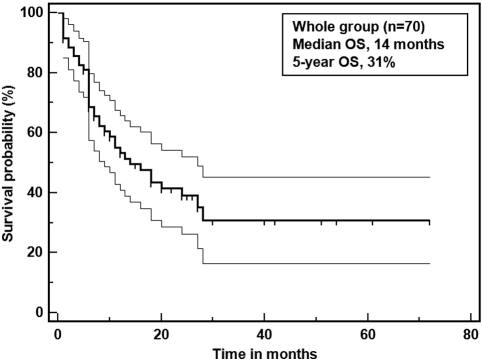

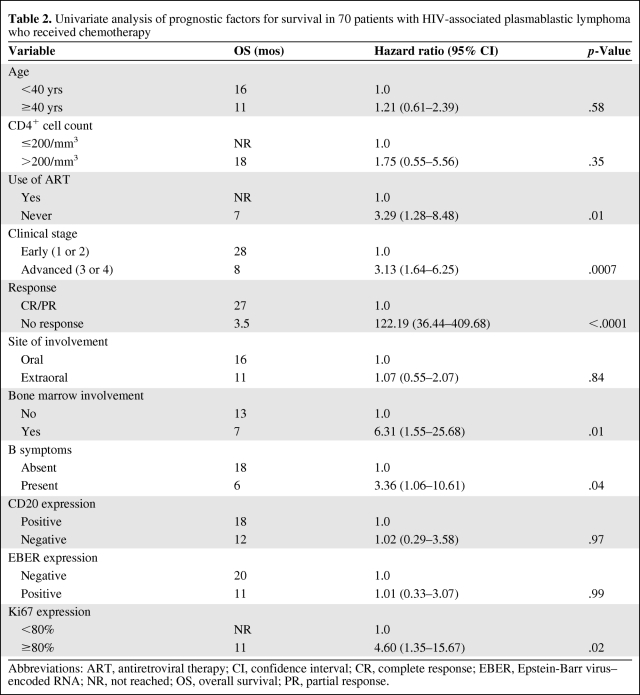

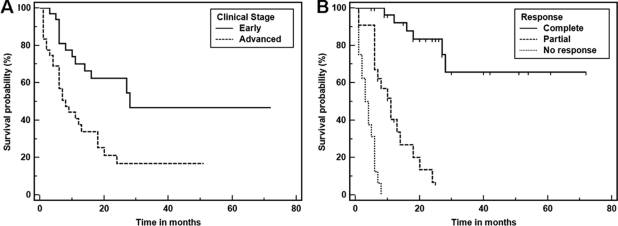

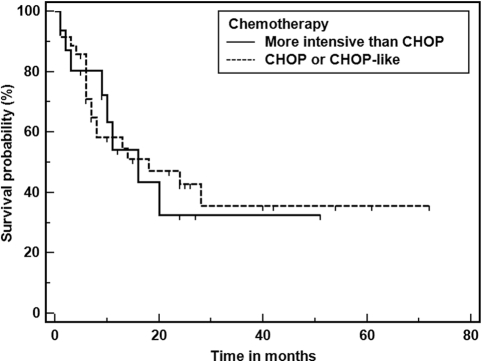

The median OS time for the entire group was 14 months, with a 5-year OS rate of 31% (Fig. 1). In the univariate analysis (Table 2), the variables associated with longer survival were early clinical stage (Fig. 2A) and a CR to chemotherapy (Fig. 2B). When evaluating survival in patients obtaining a CR and a PR, there was a statistically significant survival advantage for the former group (median OS time, not reached versus 11 months; p < .0001). Patients obtaining a PR had a significantly longer survival time than patients who did not achieve a response (median OS time, 11 months versus 3.5 months; p < .0001). Although a very small subset (n = 5), patients with HIV-associated PBL who carried a MYC/IgH translocation had a very poor median OS time of 3 months (data not shown). When evaluating the role of chemotherapy, regimens more intensive than CHOP did not seem to confer a survival advantage (Fig. 3); there was no difference in the clinical stage distribution between the two groups (p = .66).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival (OS) estimate in 70 patients with HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma treated with chemotherapy.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors for survival in 70 patients with HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma who received chemotherapy

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; EBER, Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; PR, partial response.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimate in patients with HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma treated with chemotherapy according to clinical stage (A) and response to therapy (B).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimate in 70 patients with HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma according to chemotherapy regimen received.

Abbreviation: CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.

Discussion

PBL is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder initially reported in the oral cavity of HIV-infected individuals. PBL represents a challenging diagnosis given its atypical morphology and the lack of expression of pan-B-cell-related antigens such as CD20. Pathologically, the differential diagnosis of PBL includes Burkitt's lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation, anaplastic variants of DLBCL, and poorly differentiated carcinomas. PBL also constitutes a therapeutic challenge, because patients are usually severely immunosuppressed or undergoing treatment with ART, increasing the potential for adverse events, such as opportunistic infections, and pharmacokinetic interactions with chemotherapy.

The clinicopathological characteristics of this group of patients were similar to those seen in prior reports [2, 15]. HIV-associated PBL more frequently affects younger male individuals with CD4+ cell counts <200/mm3. Oral sites are the sites most commonly involved, although extraoral PBL has emerged, likely as a result of greater recognition of this disease among clinicians and pathologists, as well as better diagnostic methods. Clinicians treat PBL similarly to other aggressive lymphomas—half the cases reported were treated with CHOP or CHOP-like regimens. However, there was a significant portion of patients who were treated with more intensive regimens, likely reflecting the overall dissatisfaction with the historical results obtained with CHOP. However, based on our results, there was no evidence of longer survival with more intensive regimens. It should be realized that higher intensity therapies were possibly given to patients with higher risk disease, who may have a worse prognosis, introducing a potential bias in our results.

Chemotherapy, however, can induce an ORR of 77%, but, despite this, the OS time remains short, at 14 months (28 months in early stages and 8 months in advanced stages). Likely explanations for this poor prognosis are: (a) the relapsing nature of PBL, which can be influenced by immunosuppression, because many relapses were seen in patients who stopped ART; (b) the chemoresistance of PBL, because the most common cause of death was lymphoma progression; and (c) the development of infectious complications, because this was the second most common cause of death.

Little is known about potential prognostic indicators in HIV-associated PBL. In fact, a recent review failed to demonstrate an association between survival and several clinicopathological characteristics [2]. A potential reason for this lack of association is that many patients did not receive chemotherapy, most likely because of their poor performance status, whereas other patients achieved sustained remissions with the institution of ART alone. In order to overcome these shortcomings, only chemotherapy-treated patients were included in this analysis.

The median OS duration seen this group of HIV-associated PBL patients is concordant with a prior report [2]. The most commonly used prognostic tool in aggressive lymphomas is the IPI score. The IPI score has also been validated, although retrospectively, in a series of reports, and is considered by many to be the standard of care for risk stratification in HIV-associated lymphoma [11, 16, 17]. Unfortunately, in our study only a small fraction of the cases had available LDH levels and performance status scores, making the evaluation of the IPI score in HIV-associated PBL impossible. Despite this obstacle, several features were associated with survival, including response to therapy and clinical stage. Among other weaker factors were the use of ART and bone marrow involvement. The latter, however, could have been just a reflection of clinical stage. As with other aggressive lymphomas, achieving a response emerged as a prognostic factor for survival, and significant survival differences were seen in patients achieving a CR versus a PR and a PR versus no response. Because the use of more intensive chemotherapy or the degree of immunosuppression does not seem to play a role in survival, a potential explanation for the different responses could be based in the biological heterogeneity inherent to PBL [18].

Recent studies have identified a group of patients with DLBCL with concurrent MYC gene rearrangements treated with rituximab plus CHOP (the R-CHOP regimen) [19]. Such patients tend to have a worse prognosis and higher rates of central nervous system involvement. Some authors have suggested treating these patients with regimens used for Burkitt's lymphoma. Five patients in our series had translocations between chromosomes 8 and 14, which are typically seen in Burkitt's lymphoma [20–23]. Those patients presented with a CD4+ cell count <200/mm3 (n = 4), advanced stage (n = 3), and extraoral involvement (n = 4), had disease associated with EBV (n = 3) and an OS time of 3 months. None of those patients achieved a CR with chemotherapy; however, they did not receive chemotherapy regimens more intensive than CHOP. It is possible that these patients could have had Burkitt's lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation misdiagnosed as PBL, although low CD4+ cell counts are not typical of Burkitt's lymphoma.

Currently, the treatment of HIV-associated PBL is not standardized, and because of the short survival duration seen, further research is needed to improve our therapies. By definition, the PBL cell of origin is a nongerminal center or activated B cell (NGC/ABC). Recent studies have reported the potential value of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in patients with DLBCL of NGC/ABC origin [24]; bortezomib elicits its antilymphoma effect by blocking nuclear factor κB and by sensitizing NGC/ABC DLBCL patients to chemotherapy. Only one patient in our series was treated with single-agent bortezomib, achieving a short-lived PR but finally succumbing to infections [21]. There is an ongoing phase I/II trial, sponsored by the AIDS Malignancies Consortium, using bortezomib in combination with ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide with or without rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory HIV-associated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00598169) [25]. A randomized phase II trial is evaluating the role of R-CHOP with or without bortezomib in patients with previously untreated NGC/ABC DLBCL (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00931918) [26]. The latter trial can include HIV+ patients that are receiving ART.

Finally, the role of rituximab is unclear in the treatment of HIV-associated PBL, but it might be of benefit in the small proportion of patients whose lymphoma cells express CD20 [1, 3, 8, 27]. However, CD4+ cell counts have to be taken into consideration prior to starting rituximab therapy [28]. Based on recent studies, the administration of rituximab seems to be safe in patients with CD4+ cell counts >100/mm3 while receiving proper antibiotic prophylaxis [29].

Conclusions

The present report adds to the current body of literature in regard to prognostic factors in HIV-associated PBL treated with chemotherapy. Several clinical factors were associated with survival, including clinical stage and the use of ART; however, obtaining a CR to chemotherapy seems to be the strongest predictor of survival. Therapies more intensive than CHOP do not seem to prolong survival. Further research is needed to understand the biology of PBL, which seems to be very heterogeneous, in order to improve therapies.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Jorge J. Castillo

Provision of study material or patients: Jorge J. Castillo, Eric S. Winer, Dariusz Stachurski

Collection and/or assembly of data: Jorge J. Castillo, Eric S. Winer, Dariusz Stachurski, Melhem Jabbour, Kimberly Perez, Cannon Milani

Data analysis and interpretation: Jorge J. Castillo, James N. Butera, Eric S. Winer, Dariusz Stachurski, Gerald Colvin

Manuscript writing: Jorge J. Castillo, James N. Butera

Final approval of manuscript: Jorge J. Castillo, James N. Butera, Eric S. Winer, Dariusz Stachurski, Melhem Jabbour, Kimberly Perez, Cannon Milani, Gerald Colvin

References

- 1.Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: A new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castillo J, Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: Lessons learned from 112 published cases. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:804–809. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong R, Bradrick J, Liu YC. Spontaneous regression of an HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma in the oral cavity: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1361–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilaberte M, Gallardo F, Bellosillo B, et al. Recurrent and self-healing cutaneous monoclonal plasmablastic infiltrates in a patient with AIDS and Kaposi sarcoma. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:828–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasta SD, Carrum GM, Shahab I, et al. Regression of a plasmablastic lymphoma in a patient with HIV on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:423–426. doi: 10.1080/10428190290006260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RS, Power DA, Spittle HF, et al. Absence of immunohistochemical evidence for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) in oral cavity plasmablastic lymphoma in an HIV-positive man. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2000;12:194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaidano G, Cerri M, Capello D, et al. Molecular histogenesis of plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:622–628. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lester R, Li C, Phillips P, et al. Improved outcome of human immunodeficiency virus-associated plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: A report of two cases. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:1881–1885. doi: 10.1080/10428190410001697395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojanguren J, Collazos J, Martinez C, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-related plasmablastic lymphomas arising from long-standing sacrococcygeal cysts in immunosuppressed patients. AIDS. 2003;17:1582–1584. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000076304.76477.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panos G, Karveli EA, Nikolatou O, et al. Prolonged survival of an HIV-infected patient with plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:761–765. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mounier N, Spina M, Gabarre J, et al. AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Final analysis of 485 patients treated with risk-adapted intensive chemotherapy. Blood. 2006;107:3832–3840. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohlius J, Schmidlin K, Costagliola D, et al. Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) study group. Prognosis of HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients starting combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2009;23:2029–2037. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e531c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris N, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Fourth Edition. Lyon, France: IARC; 2008. pp. 256–257. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adam P, Katzenberger T, Seeberger H, et al. A case of a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of plasmablastic type associated with the t(2;5)(p23;q35) chromosome translocation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1473–1476. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200311000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rafaniello Raviele P, Pruneri G, Maiorano E. Plasmablastic lymphoma: A review. Oral Dis. 2009;15:38–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bower M, Gazzard B, Mandalia S, et al. A prognostic index for systemic AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:265–273. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-4-200508160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miralles P, Berenguer J, Ribera JM, et al. Prognosis of AIDS-related systemic non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and highly active antiretroviral therapy depends exclusively on tumor-related factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:167–173. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802bb5d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang CC, Zhou X, Taylor JJ, et al. Genomic profiling of plasmablastic lymphoma using array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH): Revealing significant overlapping genomic lesions with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2009;2:47. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-2-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savage KJ, Johnson NA, Ben-Neriah S, et al. MYC gene rearrangements are associated with a poor prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy. Blood. 2009;114:3533–3537. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogusz AM, Seegmiller AC, Garcia R, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas with MYC/IgH rearrangement: Report of three cases and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:597–605. doi: 10.1309/AJCPFUR1BK0UODTS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bose P, Thompson C, Gandhi D, et al. AIDS-related plasmablastic lymphoma with dramatic, early response to bortezomib. Eur J Haematol. 2009;82:490–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson MA, Schwarer AP, McLean C, et al. AIDS-related plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity associated with an IGH/MYC translocation–treatment with autologous stem-cell transplantation in a patient with severe haemophilia-A. Haematologica. 2007;92:e11–e12. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yotsumoto M, Ichikawa N, Ueno M, et al. CD20-negative CD138-positive leukemic large cell lymphoma with plasmablastic differentiation with an IgH/MYC translocation in an HIV-positive patient. Intern Med. 2009;48:559–562. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Czuczman MS, et al. Differential efficacy of bortezomib plus chemotherapy within molecular subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2009;113:6069–6076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bortezomib, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide, with or without rituximab, in treating patients with relapsed or refractory AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma. [accessed February 11, 2010]. Available at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov.

- 26.ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to assess the effectiveness of RCHOP with or without VELCADE in previously untreated non-germinal center B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. [accessed February 11, 2010]. Available at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov.

- 27.Flaitz CM, Nichols CM, Walling DM, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma: An HIV-associated entity with primary oral manifestations. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:96–102. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan LD, Lee JY, Ambinder RF, et al. Rituximab does not improve clinical outcome in a randomized phase 3 trial of CHOP with or without rituximab in patients with HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma: AIDS-Malignancies Consortium Trial 010. Blood. 2005;106:1538–1543. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boué F, Gabarre J, Gisselbrecht C, et al. Phase II trial of CHOP plus rituximab in patients with HIV-associated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4123–4128. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]