This paper reviews the adverse outcomes associated with polypharmacy and presents polypharmacy definitions offered by the geriatrics literature, examining the strengths and weaknesses of the various definitions, as well as exploring the relationships among these definitions and what is known about the prevalence and impact of polypharmacy in the geriatric-oncology population.

Keywords: Polypharmacy, Cancer, Oncology, Geriatrics, Medications, Therapy

Learning Objectives

After completing this course, the reader will be able to:

Differentiate the multiple definitions of polypharmacy in order to be able to recognize it in your patient population.

Discuss the current data available in evaluating polypharmacy specifically in older adults with cancer and incorporate the data in your evaluation of older patients.

Summarize the agents or drug classes that may be deemed inappropriate in older adults to avoid prescribing medications for older patients that may lead to adverse drug events.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com

Abstract

The definition of “polypharmacy” ranges from the use of a large number of medications; the use of potentially inappropriate medications, which can increase the risk for adverse drug events; medication underuse despite instructions to the contrary; and medication duplication. Older adults are particularly at risk because they often present with several medical conditions requiring pharmacotherapy. Cancer-related therapy adds to this risk in older adults, but few studies have been conducted in this patient population. In this review, we outline the adverse outcomes associated with polypharmacy and present polypharmacy definitions offered by the geriatrics literature. We also examine the strengths and weaknesses of these definitions and explore the relationships among these definitions and what is known about the prevalence and impact of polypharmacy.

Introduction

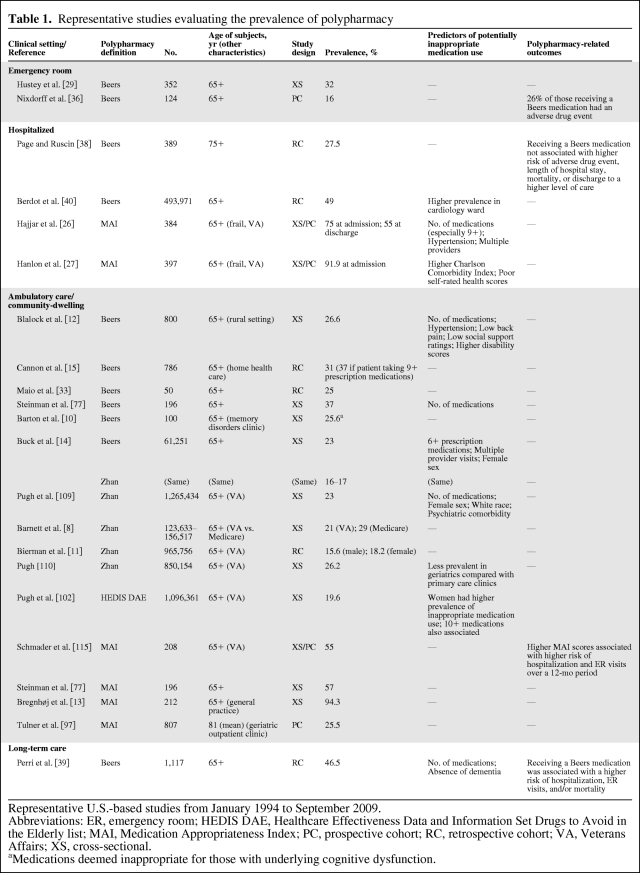

The term “polypharmacy” can be defined in several ways, including an increased number of medications; the use of potentially inappropriate medications, which can increase the risk for adverse drug events; medication underuse; and medication duplication [1, 2]. Older adults are more likely to experience polypharmacy because they tend to have more medical conditions requiring pharmacotherapy [3–7]. The prevalence of polypharmacy in older adults ranges from 13% to 92% [8–39], depending on the definition of polypharmacy used and the characteristics of the study population evaluated (Table 1). Several adverse outcomes have been linked to polypharmacy, including increases in health care costs and adverse drug events, often leading to increased morbidity [7, 17, 18, 20, 24, 36, 39–62]. However, the evidence for a strong association between polypharmacy and an increased risk of mortality independent of other concomitant risk factors such as comorbidity remains unclear [30, 37, 39, 63–65].

Table 1.

Representative studies evaluating the prevalence of polypharmacy

Representative U.S.-based studies from January 1994 to September 2009.

Abbreviations: ER, emergency room; HEDIS DAE, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set Drugs to Avoid in the Elderly list; MAI, Medication Appropriateness Index; PC, prospective cohort; RC, retrospective cohort; VA, Veterans Affairs; XS, cross-sectional.

aMedications deemed inappropriate for those with underlying cognitive dysfunction.

Cancer-related therapy adds to the risk of polypharmacy in older adults, as many new medications may be prescribed, including cancer therapy and supportive medications [66–70], but studies reporting on polypharmacy specifically in older adults with cancer remain sparse [71–74]. This review offers definitions of polypharmacy proposed in the geriatrics literature, examines the strengths and weaknesses of these definitions, and explores the relationship among these definitions and what is known about the prevalence and impact of polypharmacy. In addition, we describe tools for evaluating polypharmacy in daily practice and propose research into how this information can be applied in the geriatric oncology population.

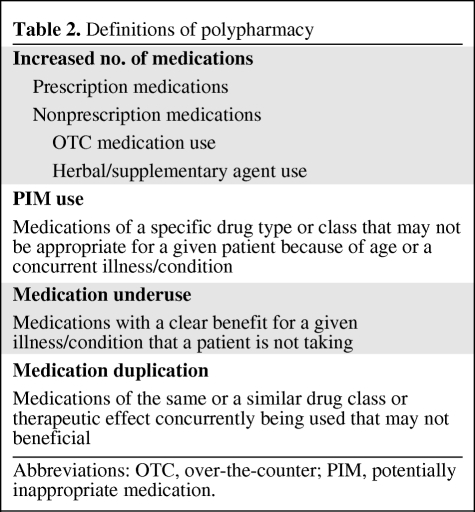

Defining Polypharmacy

Several definitions of polypharmacy have been proposed (Table 2). It was initially defined as the number of medications being used concomitantly [75, 76]. Over time, the definition of polypharmacy shifted to include specific medications or scenarios thought to be more clinically relevant, such as the use of potentially inappropriate medications associated with a high risk of adverse effects in older adults [26, 77]. For example, two patients in their 70s both could be taking five prescription medications, yet their risk for an adverse drug event would be markedly different. The first hypothetical patient with breast cancer, hypertension, and coronary artery disease could be taking aspirin, atorvastatin, metoprolol, lisinopril, and anastrozole. The other could have breast cancer along with depression, atrial fibrillation, and peripheral arterial disease, and be taking amitriptyline, diazepam, warfarin, aspirin, and capecitabine. The second patient could potentially be at increased risk compared with the first patient because of (a) potentially sedating medications (amitriptyline and diazepam); (b) an anticholinergic medication (amitriptyline); and (c) medications that concomitantly augment bleeding risk because of a specific drug-chemotherapy interaction (capecitabine increasing the anticoagulant effects of warfarin) [78].

Table 2.

Definitions of polypharmacy

Abbreviations: OTC, over-the-counter; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication.

The clinical significance of distinguishing the “number of medications” from the actual medications taken has not gone unnoticed. A recent review pointed out that many studies use the terms “polypharmacy” and “inappropriate drug use” interchangeably [79]. This confusion is further highlighted in a review that has shown that the definition of polypharmacy in studies can be related either to the number or to the type of medications taken (i.e., medications with a high risk of adverse drug events or unnecessary medications), both of which can lead to an adverse drug event [80]. Table 2 illustrates the multifaceted components of how to define polypharmacy. The inherent difficulties of multiple definitions of polypharmacy become more evident when they are compared [81]. These definitions are described below.

Evaluating Polypharmacy: Current Methods

Number of Medications

Many community-dwelling older adults take multiple prescription medications [1, 2]. The likelihood of older adults receiving prescriptions from multiple providers compounds the risk of polypharmacy [4, 7]. In addition, an increasing number of medications has been associated with a higher frequency of potentially inappropriate medication use [15, 27, 39, 82]. A large number of medications may also place older adults at risk for drug-related complications, seen in a variety of clinical settings [42, 44, 55, 61, 62, 83].

The number of medications is also associated with a higher risk of a more subtle adverse drug event: medication nonadherence [34, 84–86]. This association may be related to the finding that many medication discrepancies (i.e., a discrepancy between what is prescribed and what is actually being taken) are identified in those receiving higher numbers of outpatient prescriptions [87]. As a result, nonadherence is a potential issue for older adults, especially because it has been associated with adverse health-related outcomes, including increased emergency room visits, hospitalization rates, and the potential for increased morbidity and mortality [88].

Nonprescription medication use, excluding herbal or complementary agents, should also be accounted for when considering the number of medications. Approximately 48% to 63% of older adults take at least one vitamin/mineral; 26% to 36% take an herbal, complementary, or alternative medication; and up to 50% take two to four over-the-counter medications on a regular basis [1, 89]. The likelihood of taking such agents increases with age [90]. The use of nonprescription medications increases not only the total number of medications taken but also the risk for drug interactions [90–92]. However, older adults with multiple medical conditions may require this level of pharmacotherapy. As a result, additional definitions of polypharmacy have been developed, including the use of “unnecessary” or potentially inappropriate medication use described below.

Potentially Inappropriate Medications

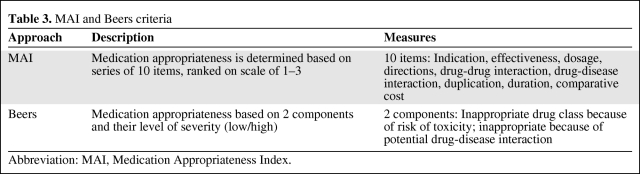

Two of the approaches most frequently used to evaluate potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults have been the Beers criteria and the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) described below (Table 3).

Table 3.

MAI and Beers criteria

Abbreviation: MAI, Medication Appropriateness Index.

Beers Criteria and Its Derivations

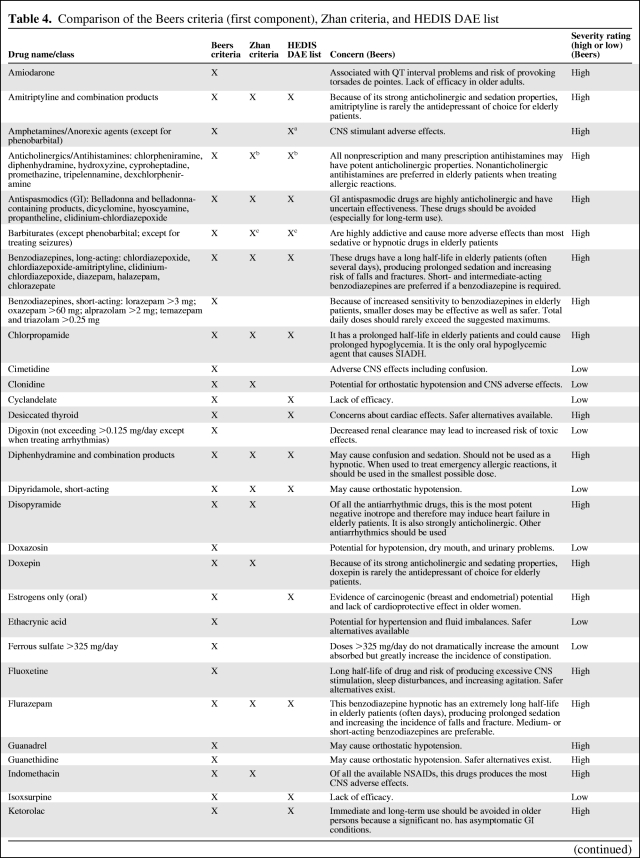

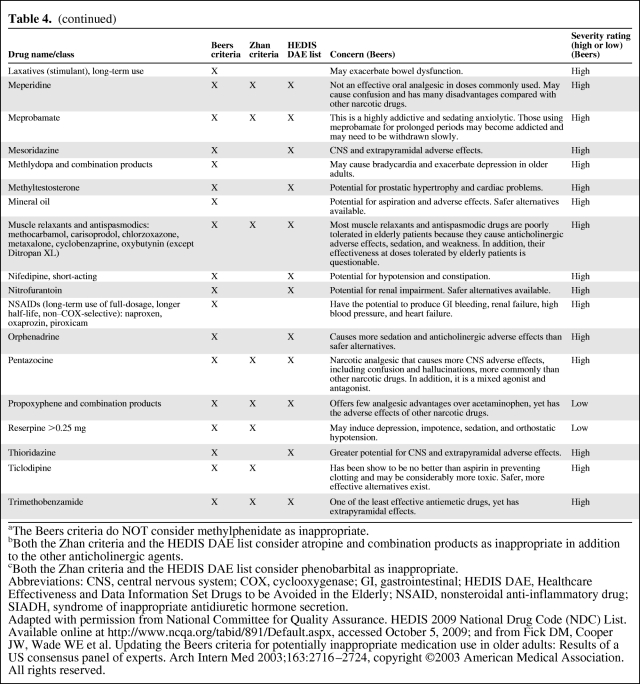

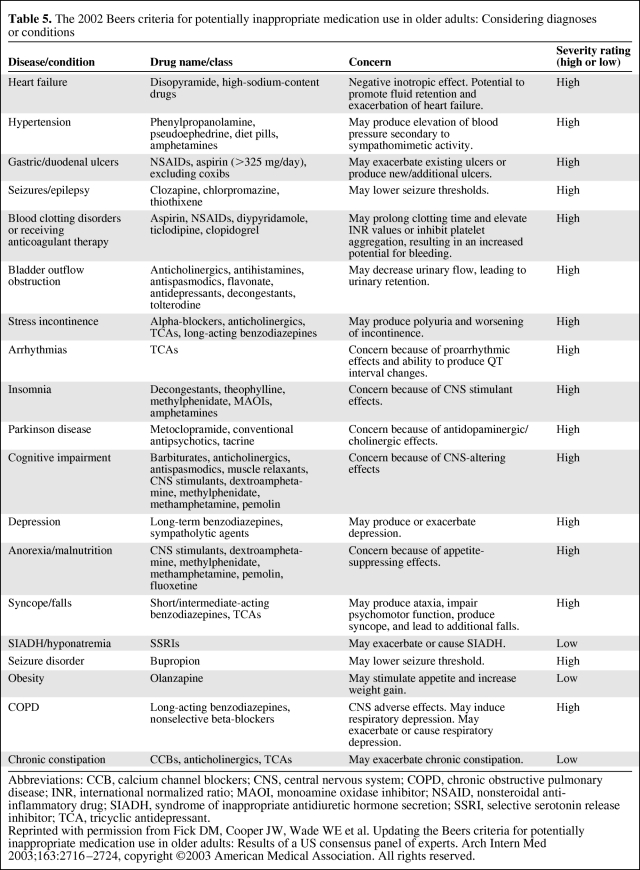

The Beers criteria consist of a list of medications deemed inappropriate for use in older adults, divided into 2 components: (a) specific drugs or drug classes that are considered inappropriate for use in older adults because they are either ineffective or pose unnecessarily high risk where a safer alternative exists; and (b) drugs that may be inappropriate for use in older adults based on the presence of coexisting diseases or conditions [93]. The Beers criteria have been updated twice since 1991 [93–95]. The most recently updated first and second components of the Beers criteria are outlined below (Tables 4 and 5, respectively). Polypharmacy studies using the most recent Beers criteria have been reported in a variety of clinical settings across several countries [8–10, 12, 14–25, 28–30, 32, 34–39, 46, 77, 96–103].

Table 4.

Comparison of the Beers criteria (first component), Zhan criteria, and HEDIS DAE list

Table 4.

(continued)

aThe Beers criteria do NOT consider methylphenidate as inappropriate.

bBoth the Zhan criteria and the HEDIS DAE list consider atropine and combination products as inappropriate in addition to the other anticholinergic agents.

cBoth the Zhan criteria and the HEDIS DAE list consider phenobarbital as inappropriate.

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; COX, cyclooxygenase; GI, gastrointestinal; HEDIS DAE, Healthcare Effectiveness and Data Information Set Drugs to be Avoided in the Elderly; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

Adapted with permission from National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS 2009 National Drug Code (NDC) List.

Available online at http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/891/Default.aspx, accessed October 5, 2009; and from Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE et al. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: Results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2716–2724, copyright ©2003 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Table 5.

The 2002 Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: Considering diagnoses or conditions

Abbreviations: CCB, calcium channel blockers; CNS, central nervous system; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; INR, international normalized ratio; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion; SSRI, selective serotonin release inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Reprinted with permission from Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE et al. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: Results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2716–2724, copyright ©2003 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

In addition to the number of medications, older adults receiving medications identified as potentially inappropriate by the Beers criteria have an increased risk for polypharmacy-related adverse outcomes [1, 2, 104], including increased rates of adverse drug reactions [17, 45, 50, 105], hospitalization [30, 39, 45–47, 53, 59, 60], emergency room visits [18, 45, 60], falls [40, 51, 56–58], fractures [52, 58], and lower scores on measures of health-related quality of life [19, 106].

The Beers criteria were further modified by Zhan et al. to develop a streamlined list of potentially inappropriate medications and to delineate medications that carry a higher risk for side effects than others [107]. The drugs listed by the Zhan criteria are compared with the Beers criteria in Table 4. The Zhan criteria identify fewer at-risk medications ultimately deemed inappropriate by expert consensus [81]. Some studies have used both the Zhan and Beers criteria concurrently [25, 81, 99, 108, 109]. The simplicity of the Zhan criteria, however, makes them an easier screening tool in population-based evaluations of polypharmacy [14, 25, 107, 109, 110].

The Beers criteria and their derivations have also been used as potential quality indicators. For example, The Healthcare Effectiveness and Data Information Set (HEDIS) is a program designed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance to identify standards of care for 71 clinical measures across 8 domains; it is used by >90% of health care insurance providers, including Medicare and Medicaid. Recently added to the HEDIS measures in 2007 and revised in 2008 is the list of “Drugs to be Avoided in the Elderly” (DAE) [111]. The DAE lists potentially inappropriate medications for older adult patients, incorporating a curtailed list of high-risk medications similar but not identical to those identified by the Beers criteria (Table 4), and can be found online as well (http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/892/Default.aspx).

In addition to evaluating for potentially inappropriate medications, the potential for clinically significant drug-drug interactions is also being evaluated by insurance plans for older adults. These plans are now incorporating Beers and “Beers-like” indices. As per an initial insurance-based analysis in 2007, almost 25% of approximately 30,000 beneficiaries received at least one prescription for a medication considered inappropriate by the Beers criteria, and up to 6% were reported as having had an adverse drug event [112]. As a result, the HEDIS program has adopted such quality measures to curtail potentially inappropriate medication use and thus adverse drug events among older adults.

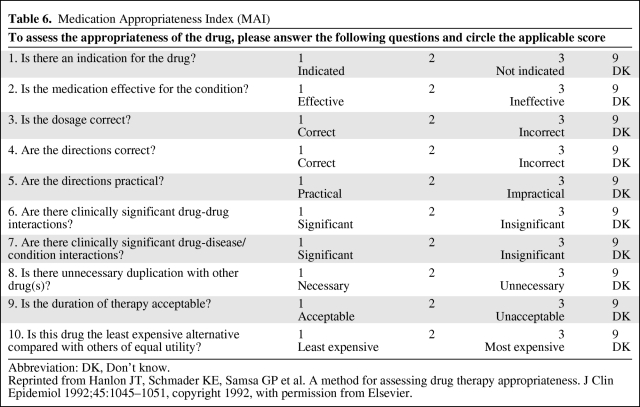

Medication Appropriateness Index

The MAI uses 10 items to assess the degree of appropriateness of a particular medication along a 3-point Likert rating scale (Table 6) [113]. If a medication receives at least one “inappropriate” score on any item, it is deemed inappropriate overall. Several modifications have since been applied to the original MAI. Some studies have incorporated the following modifications: (a) taking into account that some items may be more suitable in particular clinical contexts than others [114, 115]; (b) summating the item scores to create an overall single score of medication appropriateness [60, 115, 116]; and (c) condensing the parameters to just three (indication, efficacy, therapeutic duplication) [26, 116]. The MAI has been applied in several clinical scenarios, including in hospitalized [26, 27, 96, 113, 114, 117] and ambulatory patients [3, 13, 60, 77, 97, 115, 116, 118], as well as used in evaluating medications taken as-needed in addition to regularly scheduled medications [117].

Table 6.

Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI)

Abbreviation: DK, Don't know.

Reprinted from Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:1045–1051, copyright 1992, with permission from Elsevier.

Unlike the Beers criteria, the MAI has not been extensively evaluated in outcomes-based studies. However, higher MAI scores have also been associated with higher rates of hospitalization and emergency room visits as well as a higher risk of adverse drug reactions [97, 116]. Moreover, higher MAI scores are associated with lower self-reported health scores among older adults [27].

Comparison of the Beers Criteria (and Derivations) Versus MAI

Shortcomings of all approaches derived from the Beers criteria include the following: (a) the list is not entirely exhaustive and needs to be updated periodically as new drugs are introduced; (b) it does not assess specific aspects of polypharmacy such as inappropriate dosing, which the MAI assesses; (c) it does not take into account that some “inappropriate” medications may prove beneficial for a particular patient under specific circumstances [1, 2, 77, 119].

Some weaknesses of the MAI include the following: (a) not enough data may be present to apply all 10 of the items; (b) it takes approximately 10 minutes to apply the MAI to each medication; (c) many studies have used more than one evaluator to ensure consistent scoring; and (c) it has been studied primarily in older veterans [26, 27, 60, 113, 116, 120].

Medication Duplication or Underuse

Medication duplicity, which can lead to unnecessary medication use and thus increase the risk of adverse drug events and potential drug interactions, is a criterion evaluated by the MAI, but this component of polypharmacy may still be overlooked. The Unnecessary Drug Use Measure is a modified form of the MAI developed specifically to incorporate these properties in the assessment of polypharmacy [121].

Neither the Beers criteria nor the MAI addresses the full scope for potential drug interactions as well as medication underuse, which refers to the situation in which the addition of a particular agent may actually prove beneficial for a patient with a specific disease [2, 77, 119, 122–128]. Such medication underuse has been associated with adverse effects in older adults and can contribute to drug-related hospitalizations beyond those attributable to adverse drug reactions or nonadherence [129–131]. Separate measures have been developed to address this component specifically [117, 132, 133]. Furthermore, studies have shown discordant results among these different approaches in evaluating the prevalence of polypharmacy. As a result, a combined and/or more comprehensive approach using one or more criteria should be considered [81, 119]. For example, the Screening Tool of Older Persons' Prescriptions (STOPP) and Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment (START) criteria have recently been formulated to address multiple components of potentially inappropriate medication use/duplicity and medication underuse, respectively [134–136].

Herbal and Complementary/Alternative Medications

Herbal or complementary/alternative medication (CAM) is becoming increasingly prevalent among adults in the U.S. [89, 137–139]. Studies from the 1990s and early 2000s demonstrated that herbal/CAM use among older adults ranged from 6% to 15% [137, 138]. More recent studies report prevalence rates of 26% to 36% [89, 139]. However, this number may underestimate the true prevalence as demonstrated by a study that reported more than half of older adults do not disclose such use to their physicians [137].

An evaluation of herbal/CAM use is not typically included in standard definitions of polypharmacy described above. However, herbal/CAM use can increase the risk for drug interactions [90, 138]. Many of these interactions pertain to herbal agents such as garlic, ginkgo, and ginseng, which increase the bleeding risk associated with antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents such as aspirin and warfarin [138]. As such, herbal/CAM use should be incorporated as part of any assessment of polypharmacy.

Intervention Studies to Decrease Polypharmacy

Most intervention studies have been limited to the implementation of a pharmacist or interdisciplinary team to review medication usage, leading to reduction in the number of medications and/or use of potentially inappropriate medications among older adults in a variety of clinical settings [96, 140–147]. Overall, these studies have shown that these approaches have led to a significant reduction in suboptimal prescribing, and thus potential for adverse drug events in otherwise susceptible older adult patients. However, the impact on such intervention on clinical outcomes may depend upon the particular population. For example, the use of pharmacist-led review of prescription drug appropriateness and subsequent modification translated into less frequent adverse drug events in an outpatient setting but not in those older adults going from hospital discharge to long-term care facilities [144, 145, 147].

However, in many settings, a review of the medication list by a pharmacist or interdisciplinary team may not be available. In these situations, the implementation of electronic drug databases may be useful to help identify at-risk drugs, drug classes, dosages, and schedules [97, 148, 149]. Several electronic drug databases are available to clinicians. One study reviewed several databases and suggested that LexiComp (http://www.lexi.com), Clinical Pharmacology (http://www.clinicalpharmacology.com), and Micromedex (http://www.micromedex.com) had overall high-quality scores based on a composite evaluation of their scope, completeness, and ease-of-use in ability to answer several clinical questions [150]. However, their comparison specifically in a geriatric- or geriatric oncology–based setting has not been reported. Furthermore, the clinical significance and/or relevance of potential drug interactions and thus the “risk” of a certain drug or drug combination require clinician interpretation.

Polypharmacy in Older Adults with Cancer

Prevalence and Clinical Significance

Older adults with cancer are potentially vulnerable to the adverse effects of polypharmacy because cancer treatment often involves exposure to chemotherapy and other adjunctive or supportive medications that may increase the risk of drug interactions. Furthermore, the majority of adults with cancer are ≥65 years, with pre-existing medical conditions requiring pharmacotherapy [151]. A recent workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Aging and the National Cancer Institute reported that the prevalence and impact of medication use in the management of older adults with cancer is an unexplored area that mandates further investigation [152].

Only a few studies have evaluated the prevalence of polypharmacy specifically in geriatric oncology patients. One study reported that 63% in this group had a potential adverse drug interaction, with the majority of such patients receiving at least eight medications on average, and more than half of these interactions classified as moderate-to-severe risk [73]. When applied to outpatients receiving chemotherapy compared with supportive care only, this prevalence decreased to 27% and 31%, respectively [68, 69].

Another study evaluated the number of both prescription and nonprescription medications in older outpatients receiving chemotherapy for a variety of cancer types [74]. These patients were ≥65 years, had three comorbid conditions on average, and were receiving nine medications and at least three chemotherapeutic and/or supportive medications (mainly antiemetics). Several potential chemotherapy-drug interactions were identified; however, the frequency of adverse drug events or chemotherapy toxicity was not reported.

Most recently, the 2003 Beers criteria have been used to evaluate polypharmacy in older adults with cancer, one in an oncology-specific Acute Care for the Elderly unit and another in an outpatient setting [71, 72]. The mean age of patients evaluated was 73.5 and 74 years, respectively. Beers criteria–based prevalence of polypharmacy was 21% and 11%, respectively. Both studies were coupled with pharmacist-based interventions in medication review and subsequent modification, with 53% and 50% of patients, respectively, leading to reduction in the number of at-risk medications.

Herbal/CAM Use in Older Adults with Cancer

Herbal/CAM use can pose a significant risk in older adults with cancer. Its use in adults with cancer in the U.S. has been evaluated in several studies, with a prevalence ranging from 25% to 91%, depending on the study population and the definition of CAM used [153–189]. Only one study focused on older cancer patients, reporting a CAM prevalence of 33%, but limited the cancer type to breast, colorectal, prostate, and lung [189]. Predictors for herbal/CAM use have included the following: (a) female sex [153, 155–157, 160, 161, 164, 167, 169, 172, 181, 189]; (b) younger age [154, 156, 159, 160, 162, 172, 175, 176, 185, 186, 189]; (c) higher education levels [153, 158, 162–165, 169, 172, 176, 177, 185–187]; (d) higher income levels [165, 177, 179, 186]; (e) higher scores on measures of cancer-related physical and/or mental symptoms [153–155, 167, 170, 175, 184, 189]; and (f) advanced disease [155, 157, 162, 165]. However, none of these studies focused on herbal/CAM use in the context of polypharmacy in older adults with all cancer types or associated herbal/CAM use with outcomes.

A study evaluating outpatients undergoing chemotherapy demonstrated that almost a quarter to a half reported taking an herbal supplement or vitamin, respectively [182]. In evaluating all supplements, the 5 most frequently used supplementary agents were vitamin C (47%), a multivitamin (46%), vitamin E (42%), coenzyme Q10 (23%), and selenium (22%). When excluding vitamins, the 5 most commonly used supplementary agents were coenzyme Q10 (23%), selenium (22%), eicosapentaenoic acid (fish oil) (20%), garlic (18%), and zinc (17%).

The potential interactions of such herbal agents with chemotherapy have been reviewed [190]. For example, irinotecan has augmented gastrointestinal toxicity in patients concomitantly taking St. John's wort [191]. Those agents deemed a higher risk are those with competing cytochrome P450 and/or P-glycoprotein interactions such as garlic, ginseng, Echinacea, St. John's wort, ginkgo, and kava. This finding is of concern because garlic, ginseng, and gingko remain in the top 10 of the most frequently used herbal agents among adults nationally as of 2006 [89]. Although the prevalence of herbal/CAM use has not been fully elucidated specifically in older adults with cancer, the importance of evaluating herbal/CAM use has led some centers to provide resources for both cancer patients and their providers to evaluate an individual agent's potential benefits as well as toxicities [192].

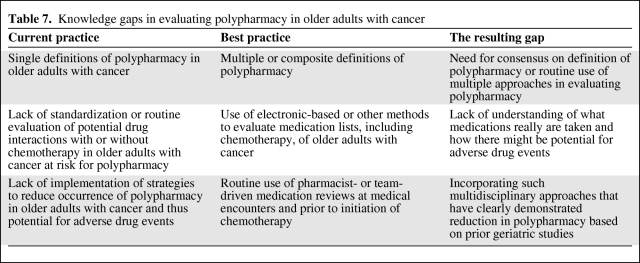

Knowledge Gaps

Several gaps remain in our knowledge of polypharmacy in the geriatric oncology population (Table 7). First, to our knowledge, no prospective, longitudinal studies have reported the association of polypharmacy with cancer therapy toxicity or other adverse drug events. Second, the risk of drug-chemotherapy and drug-drug interactions in this target population needs to be further explored. Third, prior studies have used only single methods in identifying and/or measuring polypharmacy, such as number of medications or the Beers criteria; however, multiple methods of evaluating polypharmacy may provide greater insight into the associated risk of adverse drug events and determine which approaches are more closely linked to that risk. Specific attention to over-the-counter medication or herbal/CAM use in these evaluations of polypharmacy in older adults with cancer is also needed.

Table 7.

Knowledge gaps in evaluating polypharmacy in older adults with cancer

Future Directions

Polypharmacy in its various guises is a common problem facing older adults. In this article, we describe several common definitions of polypharmacy in the geriatric population, but, regardless of definition, polypharmacy has been clearly linked with several adverse outcomes, including increased risk of adverse drug reactions [17, 45, 50, 97, 105]; medication nonadherence [34, 84–86]; hospitalization [30, 39, 45–47, 53, 59, 60]; emergency room visits [18, 45, 60, 97, 116]; falls and/or fractures [40, 51, 56–60]; and lower self-reported health scores [19, 27, 106].

Given the added degree of pharmacologic complexity that chemotherapy and cancer-specific supportive care may engender, older adults with cancer are more vulnerable to the risks associated with polypharmacy. Studies directed toward prevalence and associated outcomes in this unique group of older adults are under way (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00477958). These studies will allow better evaluation of potential drug interactions, herbal/CAM use, and predictors of polypharmacy in addition to chemotherapy toxicity in this vulnerable patient population.

Meanwhile, based on what we already know about polypharmacy in older adults with cancer, we would recommend these steps to hematologists and oncologists treating these vulnerable patients:

Perform a careful review of the patient's list of medications, including indications and dosages.

Directly inquire about over-the-counter and herbal/complementary agents.

Evaluate in advance the potential interactions between the chemotherapy regimen and other medications to minimize drug interactions and subsequent toxicity; discuss with pharmacy staff where appropriate.

Consider use of electronic drug databases that may help identify at-risk drugs, drug classes, dosages, and schedules, bearing in mind the limitations of such tools, especially if pharmacy-based support is not readily available or accessible.

Maintain an open and active line of communication with the patient's other medical providers regarding changes or additions to medication lists.

Continue to perform routine medication reconciliation at every clinical visit in conjunction with pharmacy and/or nursing staff where appropriate.

The knowledge that we have gained thus far from the geriatrics literature can facilitate oncologists in developing more effective strategies to assess, monitor, and ultimately prevent polypharmacy in older adults with cancer.

Acknowledgments

R.J.M. was supported by T32 AG19134 (National Institute on Aging geriatric research training grant) under the guidance of C.P.G., A.H., and Thomas Gill; C.P.G. was supported by 1 K08 AG24842 (Paul Beeson Career Development Award in Aging Research). A.H. was supported by K23 AG026749–01 (Paul Beeson Career Development Award in Aging Research).

Author contributions

Conception/Design: Ronald J. Maggiore, Arti Hurria, Cary P. Gross

Provision of study material or patients: Ronald J. Maggiore

Collection/Assembly of data: Ronald J. Maggiore

Data analysis and interpretation: Ronald J. Maggiore

Manuscript writing: Ronald J. Maggiore, Arti Hurria, Cary P. Gross

Final approval of manuscript: Arti Hurria, Cary P. Gross

References

- 1.Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Ruby CM, et al. Suboptimal prescribing in older inpatients and outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:200–209. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald LS, Hanlon JT, Shelton PS, et al. Reliability of a modified medication appropriateness index in ambulatory older persons. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:543–548. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurwitz JH. Polypharmacy: a new paradigm for quality drug therapy in the elderly? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1957–1959. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jörgensen T, Johansson S, Kennerfalk A, et al. Prescription drug use, diagnoses, and healthcare utilization among the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:1004–1009. doi: 10.1345/aph.10351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigler SK, Perera S, Jachna C, et al. Comparison of the association between disease burden and inappropriate medication use across three cohorts of older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2004;2:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safran DG, Neuman P, Schoen C, et al. Prescription drug coverage and seniors: findings from a 2003 national survey. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W5-152–W5-166. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett MJ, Perry PJ, Langstaff JD, et al. Comparison of rates of potentially inappropriate medication use according to the Zhan criteria for VA versus private sector medicare HMOs. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12:362–370. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.5.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry PJ, O'Keefe N, O'Connor KA, et al. Inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a comparison of the Beers criteria and the improved prescribing in the elderly tool (IPET) in acutely ill elderly hospitalized patients. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2006;31:617–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton C, Sklenicka J, Sayegh P, et al. Contraindicated medication use among patients in a memory disorders clinic. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2008;6:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bierman AS, Pugh MJ, Dhalla I, et al. Sex differences in inappropriate prescribing among elderly veterans. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blalock SJ, Byrd JE, Hansen RA, et al. Factors associated with potentially inappropriate drug utilization in a sample of rural community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2005;3:168–179. doi: 10.1016/s1543-5946(05)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bregnhøj L, Thirstrup S, Kristensen MB, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate prescribing in primary care. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:109–115. doi: 10.1007/s11096-007-9108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buck MD, Atreja A, Brunker CP, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication prescribing in outpatient practices: prevalence and patient characteristics based on electronic health records. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cannon KT, Choi MM, Zuniga MA. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly patients receiving home health care: a retrospective data analysis. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carey IM, De Wilde S, Harris T, et al. What factors predict potentially inappropriate primary care prescribing in older people? analysis of UK primary care patient record database. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:693–706. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang CM, Liu PY, Yang YH, et al. Potentially inappropriate drug prescribing among first-visit elderly outpatients in Taiwan. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:848–855. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.9.848.36095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen YC, Hwang SJ, Lai HY, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication for emergency department visits by elderly patients in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:53–61. doi: 10.1002/pds.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chin MH, Wang LC, Jin L, et al. Appropriateness of medication selection for older persons in an urban academic emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1232–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corsonello A, Pedone C, Lattanzio F, et al. Potentially inappropriate medications and functional decline in elderly hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1007–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Oliveira Martins S, Soares MA, Foppe van Mil JW, et al. Inappropriate drug use by Portuguese elderly outpatients: effect of the Beers criteria update. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28:296–301. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Wilde S, Carey IM, Harris T, et al. Trends in potentially inappropriate prescribing amongst older UK primary care patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:658–667. doi: 10.1002/pds.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egger SS, Bachmann A, Hubmann N, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly patients: comparison between general medical and geriatric wards. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:823–837. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623100-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallagher PF, Barry PJ, Ryan C, et al. Inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of elderly patients as determined by Beers' Criteria. Age Ageing. 2008;37:96–101. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goulding MR. Inappropriate medication prescribing for elderly ambulatory care patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:305–312. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Sloane RJ, et al. Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1518–1523. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanlon JT, Artz MB, Pieper CF, et al. Inappropriate medication use among frail elderly inpatients. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:9–14. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosia-Randell HM, Muurinen SM, Pitkälä KH. Exposure to potentially inappropriate drugs and drug-drug interactions in elderly nursing home residents in Helsinki, Finland: a cross-sectional study. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:683–692. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825080-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hustey FM, Wallis N, Miller J. Inappropriate prescribing in an older ED population. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:804–807. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klarin I, Wimo A, Fastbom J. The association of inappropriate drug use with hospitalisation and mortality: a population-based study of the very old. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:69–82. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin HY, Liao CC, Cheng SH, et al. Association of potentially inappropriate medication use with adverse outcomes in ambulatory elderly patients with chronic diseases: experience in a Taiwanese medical setting. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:49–59. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maio V, Yuen EJ, Novielli K, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication prescribing for elderly outpatients in Emilia Romagna, Italy: a population-based cohort study. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:915–924. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623110-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maio V, Hartmann CW, Poston S, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients in 2 outpatient settings. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21:162–168. doi: 10.1177/1062860605285475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mansur N, Weiss A, Beloosesky Y. Is there an association between inappropriate prescription drug use and adherence in discharged elderly patients? Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:177–184. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niwata S, Yamada Y, Ikegami N. Prevalence of inappropriate medication using Beers criteria in Japanese long-term care facilities. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nixdorff N, Hustey FM, Brady AK, et al. Potentially inappropriate medications and adverse drug effects in elders in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:697–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onder G, Landi F, Liperoti R, et al. Impact of inappropriate drug use among hospitalized older adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:453–459. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0928-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Page RL, II, Ruscin JM. The risk of adverse drug events and hospital-related morbidity and mortality among older adults with potentially inappropriate medication use. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perri M, III, Menon AM, Deshpande AD, et al. Adverse outcomes associated with inappropriate drug use in nursing homes. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:405–411. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berdot S, Bertrand M, Dartigues JF, et al. Inappropriate medication use and risk of falls: a prospective study in a large community-dwelling elderly cohort. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-9-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bootman JL, Harrison DL, Cox E. The health care cost of drug-related morbidity and mortality in nursing facilities. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2089–2096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buajordet I, Ebbesen J, Erikssen J, et al. Fatal adverse drug events: the paradox of drug treatment. J Intern Med. 2001;250:327–341. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carbonin P, Pahor M, Bernabei R, et al. Is age an independent risk factor of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized medical patients? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:1093–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb02875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Courtman BJ, Stallings SB. Characterization of drug-related problems in elderly patients on admission to a medical ward. Can J Hosp Pharm. 1995;48:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fick DM, Mion LC, Beers MH, et al. Health outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31:42–51. doi: 10.1002/nur.20232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fillenbaum GG, Hanlon JT, Landerman LR, et al. Impact of inappropriate drug use on health services utilization among representative older community-dwelling residents. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2004;2:92–101. doi: 10.1016/s1543-5946(04)90014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flaherty JH, Perry HM, III, Lynchard GS, et al. Polypharmacy and hospitalization among older home care patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M554–M559. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.10.m554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.French DD, Campbell R, Spehar A, et al. Outpatient medications and hip fractures in the US: a national veterans study. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:877–885. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522100-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griep MI, Mets TF, Collys K, et al. Risk of malnutrition in retirement homes elderly persons measured by the “mini-nutritional assessment.”. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M57–M63. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.2.m57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, Hajjar ER, et al. Incidence and predictors of all and preventable adverse drug reactions in frail elderly persons after hospital stay. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:511–515. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.5.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hartikainen S, Lönnroos E, Louhivuori K. Medication as a risk factor for falls: critical systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1172–1181. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacqmin-Gadda H, Fourrier A, Commenges D, et al. Risk factors for fractures in the elderly. Epidemiology. 1998;9:417–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jensen GL, Friedmann JM, Coleman CD, et al. Screening for hospitalization and nutritional risks among community-dwelling older persons. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:201–205. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kongkaew C, Noyce PR, Ashcroft DM. Hospital admissions associated with adverse drug reactions: a systematic review of prospective observational studies. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1017–1025. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Langmore SE, Terpenning MS, Schork A, et al. Predictors of aspiration pneumonia: how important is dysphagia? Dysphagia. 1998;13:69–81. doi: 10.1007/PL00009559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II, cardiac and analgesic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:40–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I, psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:30–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lloyd BD, Williamson DA, Singh NA, et al. Recurrent and injurious falls in the year following hip fracture: a prospective study of incidence and risk factors from the Sarcopenia and Hip Fracture study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:599–609. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Onder G, Pedone C, Landi F, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of hospital admissions: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly (GIFA) J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1962–1968. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmader KE, Hanlon JT, Landsman PB, et al. Inappropriate prescribing and health outcomes in elderly veteran outpatients. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:529–533. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shorr RI, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, et al. Incidence and risk factors for serious hypoglycemia in older persons using insulin or sulfonylureas. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1681–1686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Veehof LJ, Stewart RE, Meyboom-de Jong B, et al. Adverse drug reactions and polypharmacy in the elderly in general practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;55:533–536. doi: 10.1007/s002280050669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Espino DV, Bazaldua OV, Palmer RF, et al. Suboptimal medication use and mortality in an older adult community-based cohort: results from the Hispanic EPESE Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:170–175. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanlon JT, Fillenbaum GG, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Impact of inappropriate drug use on mortality and functional status in representative community dwelling elders. Med Care. 2002;40:166–176. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lau DT, Kasper JD, Potter DE, et al. Hospitalization and death associated with potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions among elderly nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:68–74. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Corcoran ME. Polypharmacy in the older patient with cancer. Cancer Control. 1997;4:419–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lichtman SM, Boparai MK. Anticancer drug therapy in the older cancer patient: pharmacology and polypharmacy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2008;9:191–203. doi: 10.1007/s11864-008-0060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Riechelmann RP, Tannock IF, Wang L, et al. Potential drug interactions and duplicate prescriptions among cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:592–600. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Riechelmann RP, Zimmermann C, Chin SN, et al. Potential drug interactions in cancer patients receiving supportive care exclusively. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:535–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tam-McDevitt J. Polypharmacy, aging, and cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008;22:1052–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Flood KL, Carroll MB, Le CV, et al. Polypharmacy in hospitalized older adult cancer patients: experience from a prospective, observational study of an oncology-acute care for elders unit. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lichtman SM, Boparai MK. Geriatric medication management: evaluation of pharmacist interventions and potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use in older (≥65 years) cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 Abstract 9507. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Riechelmann RP, Moreira F, Smaletz O, et al. Potential for drug interactions in hospitalized cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56:286–290. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0998-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sokol KC, Knudsen JF, Li MM. Polypharmacy in older oncology patients and the need for an interdisciplinary approach to side-effect management. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2007;32:169–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2007.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stewart RB. Polypharmacy in the elderly: a fait accompli? DICP. 1990;24:321–323. doi: 10.1177/106002809002400320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Gray S. Adverse drug reactions. In: Delafuente JC, Stewart RB, editors. Therapeutics in the Elderly. 3rd ed. Cincinnati, OH: Harvey Whitney Books; 2000. pp. 289–314. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Steinman MA, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE, et al. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1516–1523. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Camidge R, Reigner B, Cassidy J, et al. Significant effect of capecitabine on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4719–4725. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bushardt RL, Massey EB, Simpson TW, et al. Polypharmacy: misleading, but manageable. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:383–389. doi: 10.2147/cia.s2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fulton MM, Allen ER. Polypharmacy in the elderly: a literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17:123–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1041-2972.2005.0020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Steinman MA, Rosenthal GE, Landefeld CS, et al. Agreement between drugs-to-avoid criteria and expert assessments of problematic prescribing. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1326–1332. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Owens NJ, Sherburne NJ, Silliman RA, et al. The Senior Care Study: the optimal use of medications in acutely ill older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:1082–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Frazier SC. Health outcomes and polypharmacy in elderly individuals: an integrated literature review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2005;31:4–11. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20050901-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dolce JJ, Crisp C, Manzella B, et al. Medication adherence patterns in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 1991;99:837–841. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.4.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gray SL, Mahoney JE, Blough DK. Medication adherence in elderly patients receiving home health services following hospital discharge. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:539–545. doi: 10.1345/aph.10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cohen I, Rogers P, Burke V, et al. Predictors of medication use, compliance and symptoms of hypotension in a community-based sample of elderly men and women. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1998;23:423–432. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.1998.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bedell SE, Jabbour S, Goldberg R, et al. Discrepancies in the use of medications: their extent and predictors in an outpatient practice. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2129–2134. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hughes CM. Medication non-adherence in the elderly: how big is the problem? Drugs Aging. 2004;21:793–811. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200421120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Slone Epidemiology Center. Boston, MA: Slone Epidemiology Center at Boston University; 2006. [Accessed September 20, 2009]. Patterns of Medication Use in the United States: A Report of the Slone Survey. Available at http://www.bu.edu/slone/SloneSurvey/SloneSurvey.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Qato DM, Alexander GC, Conti RM, et al. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:2867–2878. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rolita L, Freedman M. Over-the-counter medication use in older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34:8–17. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20080401-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoon SL, Schaffer SD. Herbal, prescribed, and over-the-counter drug use in older women: prevalence of drug interactions. Geriatr Nurs. 2006;27:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, et al. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2716–2724. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, et al. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents: UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1825–1832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly: an update. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1531–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Spinewine A, Swine C, Dhillon S, et al. Effect of a collaborative approach on the quality of prescribing for geriatric inpatients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:658–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tulner LR, Frankfort SV, Gijsen GJ, et al. Drug-drug interactions in a geriatric outpatient cohort: prevalence and relevance. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:343–355. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van der Hooft CS, Jong GW, Dieleman JP, et al. Inappropriate drug prescribing in older adults: the updated 2002 Beers criteria: a population-based cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Viswanathan H, Bharmal M, Thomas J., III Prevalence and correlates of potentially inappropriate prescribing among ambulatory older patients in the year 2001: comparison of three explicit criteria. Clin Ther. 2005;27:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wawruch M, Zikavska M, Wsolova L, et al. Adverse drug reactions related to hospital admission in Slovak elderly patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;48:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Prudent M, Dramé M, Jolly D, et al. Potentially inappropriate use of psychotropic medications in hospitalized elderly patients in France: cross-sectional analysis of the prospective, multicentre SAFEs cohort. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:933–946. doi: 10.2165/0002512-200825110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pugh MJ, Hanlon JT, Zeber JE, et al. Assessing potentially inappropriate prescribing in the elderly Veterans Affairs population using the HEDIS 2006 quality measure. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12:537–545. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.7.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Radosević N, Gantumur M, Vlahović-Palcevski V. Potentially inappropriate prescribing to hospitalised patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:733–737. doi: 10.1002/pds.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jano E, Aparasu RR. Healthcare outcomes associated with Beers' criteria: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:438–447. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Passarelli MC, Jacob-Filho W, Figueras A. Adverse drug reactions in an elderly hospitalised population: inappropriate prescription is a leading cause. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:767–777. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522090-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fu AZ, Liu GG, Christensen DB. Inappropriate medication use and health outcomes in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1934–1939. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhan C, Sangl J, Bierman AS, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in the community-dwelling elderly: findings from the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. JAMA. 2001;286:2823–2829. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kaufman MB, Brodin KA, Sarafian A. Effect of prescriber education on the use of medications contraindicated in older adults in a managed medicare population. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11:211–219. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.3.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pugh MJ, Fincke BG, Bierman AS, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in elderly veterans: are we using the wrong drug, wrong dose, or wrong duration? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pugh MJ, Rosen AK, Montez-Rath M, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing for the elderly: Effects of geriatric care at the patient and healthcare level. Med Care. 2008;46:167–173. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318158aec2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) Washington, DC: NCQA; 2009. [Accessed September 20, 2009]. HEDIS 2009 Technical Resources: Use of High-Risk Drugs in the Elderly (DAE) Available at http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/892/Default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Triller D. New York, NY: IPRO eServices; 2006. [Accessed September 20, 2009]. Decreasing Anticholinergic Drugs in the Elderly (DADE) Available at http://www.jeny.ipro.org/shared/homehealth/events/2008–04-09. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1045–1051. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Samsa GP, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, et al. A summated score for the medication appropriateness index: development and assessment of clinimetric properties including content validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:891–896. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kassam R, Martin LG, Farris KB. Reliability of a modified medication appropriateness index in community pharmacies. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:40–46. doi: 10.1345/aph.1c077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schmader K, Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, et al. Appropriateness of medication prescribing in ambulatory elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:1241–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jeffery S, Ruby CM, Hanlon JT. The impact of an interdisciplinary team on suboptimal prescribing in a long-term care facility. Consult Pharm. 1999;14:1386–1391. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bregnhøj L, Thirstrup S, Kristensen MB, et al. Reliability of a modified medication appropriateness index in primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:769–773. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0963-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Steinman MA, Rosenthal GE, Landefeld CS, et al. Conflicts and concordance between measures of medication prescribing quality. Med Care. 2007;45:95–99. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000241111.11991.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Koronkowski MJ, et al. Adverse drug events in high risk older outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:945–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Suhrie EM, Hanlon JT, Jaffe EJ, et al. Impact of a geriatric nursing home palliative care service on unnecessary medication prescribing. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sloane PD, Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, et al. Medication undertreatment in assisted living settings. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2031–2037. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Roth CP, et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:740–747. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mendelson G, Aronow WS. Underutilization of warfarin in older persons with chronic nonvalvular atrial fibrillation at high risk for developing stroke. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1423–1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb06011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mendelson G, Aronow WS. Underutilization of measurement of serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and of lipid-lowering therapy in older patients with manifest atherosclerotic disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1128–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb06652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Mendelson G, Aronow WS. Underutilization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in older patients with Q-wave anterior myocardial infarction in an academic hospital-based geriatrics practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:751–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb03811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mendelson G, Aronow WS. Underutilization of beta-blockers in older patients with prior myocardial infarction or coronary artery disease in an academic, hospital-based geriatrics practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1360–1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Feldstein A, Elmer PJ, Orwoll E, et al. Bone mineral density measurement and treatment for osteoporosis in older individuals with fractures: a gap in evidence-based practice guideline implementation. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2165–2172. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.18.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Spiegelman D, et al. Adverse outcomes of underuse of beta-blockers in elderly survivors of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1997;277:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Havranek EP, Abrams F, Stevens E, et al. Determinants of mortality in elderly patients with heart failure: the role of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2024–2028. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.18.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Grymonpre RE, Mitenko PA, Sitar DS, et al. Drug-associated hospital admissions in older medical patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:1092–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle P ACOVE Investigators. Introduction to the assessing care of vulnerable elders-3 quality indicator measurement set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:S247–S252. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lipton HL, Bero LA, Bird JA, et al. The impact of clinical pharmacists' consultations on physicians' geriatric drug prescribing: a randomized controlled trial. Med Care. 1992;30:646–658. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gallagher P, Baeyens JP, Topinkova E, et al. Inter-rater reliability of STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons' Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment) criteria amongst physicians in six European countries. Age Ageing. 2009;38:603–606. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Gallagher P, O'Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons' potentially inappropriate Prescriptions): application of acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers' criteria. Age Ageing. 2008;37:673–679. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ballagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, et al. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons' Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment): consensus validation. Int J Clinc Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46:72–83. doi: 10.5414/cpp46072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Bruno JJ, Ellis JJ. Herbal use among us elderly: 2002 National Nealth Interview Survey. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:643–648. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Elmer GW, Lafferty WE, Tyree PT, et al. Potential interactions between complementary/alternative products and conventional medicines in a Medicare population. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1617–1624. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Nahin RL, Fitzpatrick AL, Williamson JD, et al. Use of herbal medicine and other dietary supplements in community-dwelling older people: baseline data from the ginkgo evaluation of memory study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1725–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Bregnhøj L, Thirstrup S, Kristensen MB, et al. Combined intervention programme reduces inappropriate prescribing in elderly patients exposed to polypharmacy in primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Holmes HM, Sachs GA, Shega JW, et al. Integrating palliative medicine into the care of persons with advanced dementia: identifying appropriate medication use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1306–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Davis RG, Hepfinger CA, Sauer KA, et al. Retrospective evaluation of medication appropriateness and clinical pharmacist drug therapy recommendations for home-based primary care veterans. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Chrischilles EA, Carter BL, Lund BC, et al. Evaluation of the iowa medicaid pharmaceutical case management program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:337–349. doi: 10.1331/154434504323063977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Crotty M, Rowett D, Spurling L, et al. Does the addition of a pharmacist transition coordinator improve evidence-based medication management and health outcomes in older adults moving from the hospital to a long-term care facility? results of a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2004;2:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Vinks TH, Egberts TC, de Lange TM, et al. Pharmacist-based medication review reduces potential drug-related problems in the elderly: the SMOG controlled trial. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:123–133. doi: 10.2165/0002512-200926020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Stuijt CC, Franssen EJ, Egberts AC, et al. Appropriateness of prescribing among elderly patients in a Dutch residential home: observational study of outcomes after a pharmacist-led medication review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:947–954. doi: 10.2165/0002512-200825110-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Samsa GP, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a clinical pharmacist intervention to improve inappropriate prescribing in elderly outpatients with polypharmacy. Am J Med. 1996;100:428–437. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Egger T, Dormann H, Ahne G, et al. Identification of adverse drug reactions in geriatric inpatients using a computerised drug database. Drugs Aging. 2003;20:769–776. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200320100-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Weber V, White A, McIlvried R. An electronic medical record (EMR)-based intervention to reduce polypharmacy and falls in an ambulatory rural elderly population. J Gen Int Med. 2008;23:399–404. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0482-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Clauson KA, Marsh WA, Polen HH, et al. Clinical decision support tools: analysis of online drug information databases. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, et al. The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2000;88:2398–2424. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000515)88:10<2398::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Satariano WA, Muss HB. Effects of comorbidity on cancer. Presented at the NIA/NCI workshop, Exploring the Role of Cancer Centers for Integrating Aging and Cancer Research; June 13–15, 2001; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 153.Shumay DM, Maskarinec G, Gotay CC, et al. Determinants of the degree of complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with cancer. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:661–671. doi: 10.1089/107555302320825183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Wells M, Sarna L, Cooley ME, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine therapies to control symptoms in women living with lung cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30:45–55. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200701000-00008. quiz 56–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Bardia A, Greeno E, Bauer BA. Dietary supplement usage by patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy: does prognosis or cancer symptoms predict usage? J Support Oncol. 2007;5:195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Lawsin C, DuHamel K, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Demographic, medical, and psychosocial correlates to CAM use among survivors of colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:557–564. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Lafferty WE, Bellas A, Corage Baden A, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medical providers by insured cancer patients in Washington State. Cancer. 2004;100:1522–1530. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Navo MA, Phan J, Vaughan C, et al. An assessment of the utilization of complementary and alternative medication in women with gynecologic or breast malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:671–677. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Henderson JW, Donatelle RJ. Complementary and alternative medicine use by women after completion of allopathic treatment for breast cancer. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10:52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Richardson MA, Sanders T, Palmer JL, et al. Complementary/alternative medicine use in a comprehensive cancer center and the implications for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2505–2514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.13.2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Sparber A, Bauer L, Curt G, et al. Use of complementary medicine by adult patients participating in cancer clinical trials. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27:623–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Lippert MC, McClain R, Boyd JC, et al. Alternative medicine use in patients with localized prostate carcinoma treated with curative intent. Cancer. 1999;86:2642–2648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Jazieh AR, Kopp M, Foraida M, et al. The use of dietary supplements by veterans with cancer. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:560–564. doi: 10.1089/1075553041323731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Swarup AB, Barrett W, Jazieh AR. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:468–473. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000221326.64636.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Chan JM, Elkin EP, Silva SJ, et al. Total and specific complementary and alternative medicine use in a large cohort of men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2005;66:1223–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Davis GE, Bryson CL, Yueh B, et al. Treatment delay associated with alternative medicine use among veterans with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2006;28:926–931. doi: 10.1002/hed.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Fouladbakhsh JM, Stommel M, Given BA, et al. Predictors of use of complementary and alternative therapies among patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:1115–1122. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.1115-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Singh H, Maskarinec G, Shumay DM. Understanding the motivation for conventional and complementary/alternative medicine use among men with prostate cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005;4:187–194. doi: 10.1177/1534735405276358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Yates JS, Mustian KM, Morrow GR, et al. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer patients during treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:806–811. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0770-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Hedderson MM, Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, et al. Sex differences in motives for use of complementary and alternative medicine among cancer patients. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Greenlee H, White E, Patterson RE, et al. Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) Study Cohort. Supplement use among cancer survivors in the Vitamins and Lifestyle (vital) study cohort. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:660–666. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Hedderson MM, et al. Types of alternative medicine used by patients with breast, colon, or prostate cancer: predictors, motives, and costs. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:477–485. doi: 10.1089/107555302760253676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Maskarinec G, Shumay DM, Kakai H, et al. Ethnic differences in complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer patients. J Altern Complement Med. 2000;6:531–538. doi: 10.1089/acm.2000.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Miller MF, Bellizzi KM, Sufian M, et al. Dietary supplement use in individuals living with cancer and other chronic conditions: a population-based study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:483–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Matthews AK, Sellergren SA, Huo D, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among breast cancer survivors. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:555–562. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.03-9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Astin JA, Reilly C, Perkins C, et al. Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. Breast cancer patients' perspectives on and use of complementary and alternative medicine: a study by the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006;4:157–169. doi: 10.2310/7200.2006.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.McEachrane-Gross FP, Liebschutz JM, Berlowitz D. Use of selected complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments in veterans with cancer or chronic pain: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Shen J, Andersen R, Albert PS, et al. Use of complementary/alternative therapies by women with advanced-stage breast cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2002;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Swisher EM, Cohn DE, Goff BA, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among women with gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;84:363–367. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Saxe GA, Madlensky L, Kealey S, et al. Disclosure to physicians of CAM use by breast cancer patients: findings from the Women's Healthy Eating and Living Study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2008;7:122–129. doi: 10.1177/1534735408323081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Dy GK, Bekele L, Hanson LJ, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use by patients enrolled onto phase I clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4810–4815. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Gupta D, Lis CG, Birdsall TC, et al. The use of dietary supplements in a community hospital comprehensive cancer center: implications for conventional cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:912–919. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Bernstein BJ, Grasso T. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer patients. Oncology (Williston Park) 2001;15:1267–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Burstein HJ, Gelber S, Guadagnoli E, et al. Use of alternative medicine by women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1733–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906033402206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Lee MM, Chang JS, Jacobs B, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among men with prostate cancer in 4 ethnic populations. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1606–1609. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Lee MM, Lin SS, Wrensch MR, et al. Alternative therapies used by women with breast cancer in four ethnic populations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:42–47. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Diefenbach MA, Hamrick N, Uzzo R, et al. Clinical, demographic and psychosocial correlates of complementary and alternative medicine use by men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;170:166–169. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000070963.12496.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Armstrong T, Cohen MZ, Hess KR, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use and quality of life in patients with primary brain tumors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Wyatt GK, Friedman LL, Given CW, et al. Complementary therapy use among older cancer patients. Cancer Pract. 1999;7:136–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Sparreboom A, Cox MC, Acharya MR, et al. Herbal remedies in the United States: potential adverse interactions with anticancer agents. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2489–2503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Mansky PJ, Straus SE. St. John's Wort: more implications for cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1187–1188. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.16.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. New York, NY: Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; 2009. [Accessed September 20, 2009]. About herbs, botanicals, and other products. Available at http://www.mskcc.org/mskcc/html/11570.cfm. [Google Scholar]