This review examines health-related quality of life in patients with primary brain tumors.

Keywords: Quality of life, Patient-reported outcome, Brain tumor, Cognition, Side effects of treatment

Abstract

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) has become an important outcome measure in clinical trials in primary brain tumor (i.e., glioma) patients, because they have an incurable disease. HRQOL is assessed using self-reported, validated questionnaires, addressing physical, psychological, emotional, and social issues. In addition to generic HRQOL instruments, disease-specific questionnaires have been developed, including for brain tumor patients. For the analysis and interpretation of HRQOL measurements, low compliance and missing data are methodological challenges.

HRQOL in glioma patients may be negatively affected by the disease itself as well as by side effects of treatment. But treatment with surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy may improve patient functioning and HRQOL, in addition to extending survival.

Although HRQOL has prognostic significance in brain tumor patients, it is not superior to well-known clinical parameters, such as age and performance status. In clinical practice, assessing HRQOL may be helpful in the communication between doctor and patient and may facilitate treatment decisions.

Introduction

Malignant brain tumors are among the most feared diseases. Not only is the patient inflicted by an incurable malignancy, the disease directly involves the brain, thereby threatening the “being” of the patient. Malignant brain tumors can be subdivided into primary brain tumors (i.e., tumors originating in the brain) and secondary brain tumors (i.e., brain metastases from systemic malignancies). This review deals with primary brain tumors.

The most common primary brain tumors are gliomas, originating from glial tissue. With an annual incidence of about six per 100,000, this is a relatively rare malignancy when compared with lung cancer or breast cancer, which have a 10-fold higher incidence rate [1]. Nevertheless, because of its aggressive nature and the direct involvement of the central nervous system, this disease results in a disproportionate share of cancer morbidity and mortality with a serious impact on the health care system in general, and particularly on patients and their social systems.

Gliomas may be low-grade or high-grade tumors based on histopathological features. Despite the fact that the median survival time for low-grade glioma (LGG) patients may well extend to >10 years, compared with a 1- to 3-year median survival duration in high-grade glioma (HGG) patients, glioma patients cannot be cured of their disease. Despite intensive treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, tumor recurrence inevitably occurs in the vast majority of patients and they die from tumor progression. In this patient category, the aim of treatment is not only to prolong life but also to maintain quality of life as long as possible [2]. Combined radiochemotherapy and other new treatment strategies may not only increase the duration of survival but also may have severe side effects, including a risk for toxicity [3, 4]. Therefore, the benefits of extended survival and/or progression delay have to be carefully balanced against the side effects of treatments and their potential negative impact on functioning and quality of life. Hence, the concept of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) should be included as an outcome measure supplementing traditional endpoints such as (progression-free) survival time in clinical trials evaluating the effect of treatment. Measuring HRQOL emerged in the early 1990s in the medical oncology literature. In brain tumor patients, however, it has long been a neglected issue [2]. Since the beginning of this century, HRQOL has become a secondary outcome measure in a growing number of clinical trials evaluating glioma treatment [5, 6].

Outcome Measures in Glioma

Next to the classic outcome measures, such as progression free survival and overall survival, the effect of a brain tumor and its treatment on the patient's functioning and well-being should be assessed, with important distinctions made among impairment, disability, and handicap [7]. Impairments are the direct consequences of disease demonstrated by physical examination. Disability is the impact of the impairment on the patient's ability to carry out activities. Handicap is the consequence of disability on patient well-being. Impairment is considered to be a “hard” measure, compared with disability and handicap, which are more relevant for patient functioning. Impairment in a brain tumor patient can be evaluated using neurological and neuropsychological examinations. Disability can be determined using scales such as the Barthel index, an instrument designed to measure self-care ability, and the Karnofsky Performance Status Scale, an assessment tool to measure ability to carry out the activities of daily living. The Modified Rankin Handicap Scale is frequently used to measure handicap in stroke patients. Other than the Spitzer scale, which is hardly used, there is no specific disability or handicap scale for brain tumor patients [8].

Although these outcome measures provide information on the influence of the tumor on patient functioning in daily life, they do not fully reflect the effect of the tumor on patient HRQOL.

Assessing HRQOL: A Patient-Reported Outcome Approach

To measure quality of life, the concept of HRQOL was developed. HRQOL is defined as a personal self-assessed ability to function in the physical, psychological, emotional, and social domains of day-to-day life [9]. This complex patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure demands a multidimensional instrument, and preferably should be assessed using a self-reported questionnaire. As an alternative, a (semi)-structured interview could be undertaken with the patient. At present, no single gold standard tool exists to measure HRQOL. Generic and disease-specific tools need development and validation to assess HRQOL for cancer and noncancer patients.

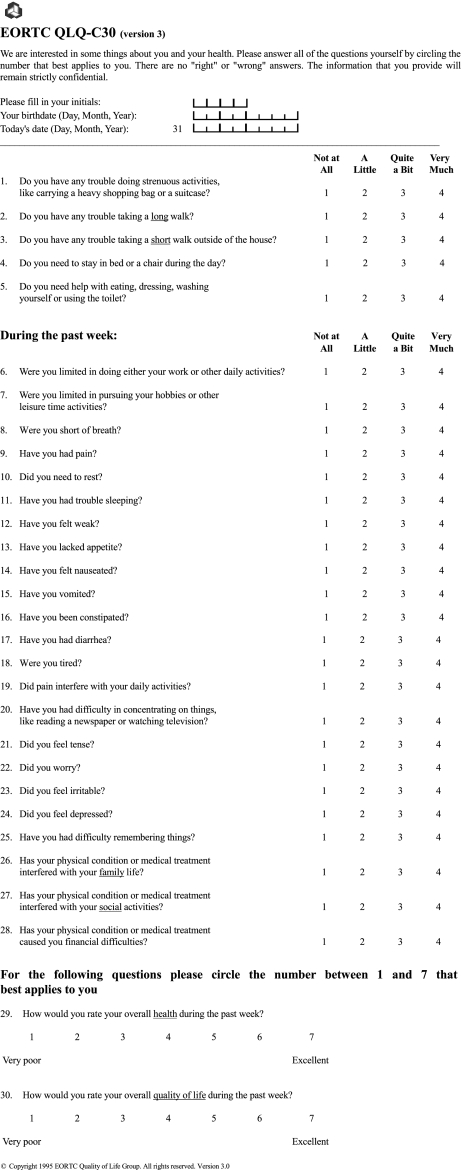

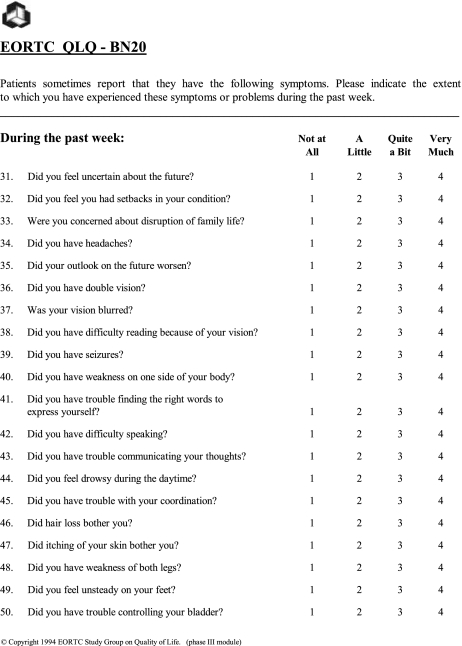

For cancer patients, the most common tool in use was developed by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) quality of life group: the EORTC QLQ-C30 [10]. The construction of this 30-item measure, designed to assess the HRQOL of cancer patients, is shown in Figure 1. The EORTC QLQ-BN20, specifically developed and validated for patients with brain cancer, includes 20 items assessing visual disorder, motor dysfunction, various disease symptoms, treatment toxicity, and future uncertainty [11] (Fig. 2). This tool, in combination with the EORTC QLQ-C30, is often used in clinical trials in glioma patients undergoing chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The items on both the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the EORTC QLQ-BN20 measures are scaled, scored, and transformed to a linear scale (0–100). Differences ≥10 points are classified as clinically meaningful changes in a HRQOL parameter. Changes >20 points are classed as large effects.

Figure 1.

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 questionnaire.

Figure 2.

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-BN20 questionnaire.

Another widely used (brain) cancer-specific HRQOL tool is the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT). In addition to a general FACT module (FACT-G), a brain cancer–specific module was developed (FACT-Br) [12]. Compared with the EORTC questionnaires, the FACT modules are more focused on psychosocial aspects and less focused on symptoms.

An alternative recently developed PRO measure for brain tumor patients is the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module (MDASI-BT), which has been validated for both primary brain tumor patients and patients with brain metastases [13, 14]. Given that this questionnaire addresses symptoms, it has similarities with the EORTC QLQ-BN20. The MDASI-BT might be useful to describe symptom occurrence throughout the disease trajectory and to evaluate interventions designed for symptom management.

When patients are unable to self-report, for example because of cognitive disturbances, one might consider using proxies or health care professionals to rate patient quality of life. In the past, this method was regarded as far from optimal. However, a review found moderate to good agreement in various studies evaluating the concordance between patient and proxy measures [15]. Mixed results have been reported for patients and health care providers. Proxies and health care providers tend to report more HRQOL problems than do patients themselves, and proxy ratings tend to be more in agreement with patient physical HRQOL domains than with psychological domains. Also, specific agreement between brain tumor patient and proxy HRQOL reports was evaluated. The EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-BN20, and FACT-Br showed moderate agreement between patient and proxy HRQOL assessments, provided cognitive functioning was not severely affected [15, 16]. The use of a nonpatient-based report should, therefore, be used only when patients are incapable of self-report.

Because it is too burdensome, one may anticipate that patients with more severe clinical symptomatology and quality of life difficulties are less likely to complete questionnaires. These patients (noncompliers), excluded from any analysis, may lead to an overestimation of the actual quality of life [16]. Indeed, the interpretation of serial measurements of HRQOL is affected by missing data [17]. Apart from the selection bias resulting from the clinical condition, in both patient and observer compliance, the filling out of questionnaires decreases over time. However, the main cause of missing data is administrative failure arising, for example, when questionnaires are not distributed by a doctor or nurse, distributed at the wrong moment, or handed out without instructions. Methodological problems may arise because of the study design, for example, using HRQOL instruments unknown to the clinicians. Other patient-related factors outside the clinical situation encompass lack of motivation on the part of the patient, misunderstanding instructions, and/or filling out questionnaires incorrectly.

Several approaches can be undertaken to minimize avoidable loss of data on quality of life [17]. Research staff and patients understanding the relevance of these data to be collected is of critical importance. When writing a research protocol, HRQOL assessment as a trial endpoint must be explicitly defined, the way of data collection must be clearly specified, and the analysis of HRQOL parameters should be described in order to prevent problems related to understanding the data and analysis discussion that may or may not be appropriate. Administrative problems can be addressed by training staff responsible for data collection to check for completeness of assessments at submission, document reasons for missing data, and structurally contact patients who miss appointments. To reduce patient-related missing data, it is important to motivate patients. At trial entry, patients should be fully informed regarding the importance of HRQOL assessments, and how and when they will be done. Multiple questionnaires addressing similar issues in a different format and/or a high frequency of assessments will result in low overall compliance.

Cognitive Functioning Versus HRQOL

Cognition encompasses functions such as language, memory, attention, and executive functioning—core functions of the human brain. Therefore, disturbances in cognition are common in patients with brain tumors and, although not as frequent as in HGG patients, are most striking in patients with LGG, because these patients usually do not suffer from neurologic deficits such as those in patients with rapidly growing, high-grade tumors. Cognitive disturbances can be caused not only by the tumor itself or by tumor-related epilepsy, but also by the tumor treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy) as well as by supportive treatment (antiepileptic drugs, corticosteroids) [18]. Cognitive disturbances can cause burdensome symptoms for patients; therefore, it is assumed that impaired cognitive function reduces quality of life. The direct relation between cognitive functioning and HRQOL in glioma patients was only demonstrated in one study [19].

HRQOL in Glioma Patients

As one would expect, the majority of newly diagnosed HGG patients have a significantly impaired level of HRQOL, compared with healthy controls [20, 21]. Systematic pretreatment evaluation of HRQOL in clinical trials illustrates clearly that the disease itself has a major negative impact and that treatment may improve HRQOL [22–24]. However, the side effects of treatment may seriously hamper (cognitive) functioning and HRQOL, especially in long-term survivors who have no active disease.

HRQOL studies of LGG patients have employed small samples with a mix of tumor grades, or have employed study-specific HRQOL measures that render comparison of results across studies difficult [25, 26]. Despite these methodological limitations, the studies conducted to date suggest that many survivors of LGG suffer from cognitive deficits, assessed both objectively and subjectively, and compromised HRQOL, for example, increased fatigue or depression [27–31]. Lower HRQOL in long-term LGG survivors is related to the extent of cognitive deficit and the severity of epilepsy [32]. Of note, the overall HRQOL in LGG survivors is not different from that in patients with hematological malignancies without involvement of the central nervous system (N.K. Aaronson, personal communication, 2009). Both LGG patients and their partners may suffer from compromised HRQOL [33].

HGG patients experience the same level of HRQOL as those with other neurological diseases of the central and peripheral nervous system [34]. When comparing HGG patients with other cancer patients, such as those with lung cancer, similar quality of life results were found [20].

Several tumor-related factors in HGG patients can have an impact on perceived HRQOL. Patients with HGG experience worse quality of life than patients who have LGG [35]. However, between patients diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme (grade IV) and patients diagnosed with anaplastic astrocytoma (grade III), no differences in HRQOL scores existed at the time of diagnosis [21]. Next to grade, tumor size and location correlate with HRQOL. Large tumors, tumors in the nondominant hemisphere, and tumors located anteriorly in the brain are associated with poorer HRQOL scores [35].

Disease-specific signs and symptoms have a major impact on quality of life. Neurological signs and symptoms, such as seizure frequency, motor deficits, and functional status, have been proven to diminish HRQOL [19, 32, 36]. Surprisingly, no deleterious effect of dysphasia on HRQOL has been established [36]. As to nonspecific signs and symptoms in patients with systemic cancers, fatigue and depression are identified as the leading factors diminishing HRQOL [37]. Also, in both LGG and HGG patients, fatigue is one of the most common symptoms and, therefore, one of the leading symptoms of decreasing quality of life [31, 38]. Clinically, significant symptoms of depression have been shown to be present in a significant portion of HGG patients, and this is probably higher than the prevalence in the general cancer population [38]. Thus, depressive symptoms are a serious clinical issue negatively affecting HRQOL in these patients and are related to shorter survival in LGG patients [38–40].

Disease recurrence has a significantly deleterious impact on patient life. Patients carry a significant symptom burden and neurological deficits are more severe at the time of recurrence than at initial presentation [19]. Not surprisingly, the HRQOL of patients with tumor recurrence is more comprised than that of patients without recurrence after the same time since diagnosis [41].

Effect of Treatment on HRQOL in Glioma Patients

Effect of Surgery on HRQOL

A reduction of the tumor mass may alleviate neurological symptoms and cognitive deficits, thereby improving quality of life. On the other hand, surgery and perioperative injuries may cause neurological deficits and focal cognitive deficits as a result of damage to normal surrounding tissue [18]. Although these deficits are often transient, they may result in a temporarily lower perceived quality of life. In a nonrandomized study, patients who had undergone a gross-total resection had both a longer survival duration and a better HRQOL than patients who only had a biopsy [42]. Clearly, these results were biased because the selection of patients for resection versus biopsy depends on factors such as tumor size, tumor location, multifocality, and performance status. Additionally, the HRQOL of patients who had undergone a gross-total resection increased over time. Therefore, it appears from that study that the benefit of resection in terms of quality of life outweighs the early side effects of surgery. Studies on the effects of surgery in LGG patients have mainly focused on cognitive functioning, mainly language. Despite extensive surgery, especially for tumors in the dominant hemisphere, dysphasia following surgery is relatively mild and in most cases transient [43].

Effect of Radiotherapy on HRQOL

Radiotherapy for LGG has been demonstrated to prolong progression-free survival but not overall survival [44]. It could be hypothesized that, by postponing progressive tumor growth, patient functioning and thereby HRQOL would be preserved by radiotherapy. Because cognition and HRQOL were not included as outcome parameters in that particular study, the results from a current EORTC/Radiation Therapy Oncology Group clinical trial in LGG patients addressing these issues are highly relevant.

Apart from beneficial effects, radiotherapy may also have a negative impact on HRQOL in LGG patients. Patients treated with high-dose radiation had a more compromised HRQOL following treatment than those on low-dose radiation, whereas overall survival did not differ between treatment arms [45]. However, most feared is a decrease in cognitive functioning and, consequently, HRQOL, resulting from irreversible radiation encephalopathy in long-term LGG survivors [46, 47].

The benefit of radiotherapy is well established in the treatment of HGG patients, because tumor progression is postponed and overall survival is extended. By stabilizing disease and delaying progression, quality of life can be maintained. Two randomized studies evaluating the combination of chemotherapy and radiation versus radiation therapy alone included HRQOL as an outcome measure [22, 23]. No negative effects of radiotherapy on quality of life were observed in anaplastic oligodendroglioma patients and in patients with glioblastoma multiforme with a good performance status. On longer follow-up, >1.5 years after the completion of radiotherapy, the HRQOL scores of HGG patients without progression even improved over their scores at the start of the treatment. In long-term (i.e., >2 years from initial treatment) HGG survivors without disease progression who had initial radiotherapy, HRQOL scores were observed to meet the level of healthy controls. This may partly be explained by response shift, that is, that patients over time more readily accept their situation [41]. Specifically in the elderly population (age >70 years), a moderate survival benefit from radiotherapy has been established for patients who have a good performance status at the start of the treatment. More importantly, HRQOL, performance status, and cognitive functions did not further deteriorate, compared with the observation arm of that study, in which patients only received supportive care [48].

The effect of reirradiation, specifically on HRQOL, was evaluated in a small study with a median follow-up of 9 months [49]. The majority of patients (80%) judged their general health status after reirradiation to be stable or even improved, compared with before treatment; in 20% of patients, their perceived general health status declined.

Effect of Chemotherapy on HRQOL

Successful chemotherapy regimens in glioma patients are the combination of procarbazine, CCNU or lomustine, and vincristine (PCV) chemotherapy and temozolomide. Compared with PCV, temozolomide has the advantage of oral administration and less bone marrow as well as subjective toxicity. In LGG patients, temozolomide chemotherapy is not only successful in terms of extending the survival duration but has been proven to maintain or even improve HRQOL while patients are on treatment [50]. Because of the chance for long-term toxicity in LGG survivors treated with radiotherapy, temozolomide is now being compared with radiotherapy in terms of both efficacy and cognition and HRQOL.

The combination of temozolomide chemotherapy and radiotherapy led to a significantly longer survival time in HGG patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme than in patients treated with radiotherapy alone [3]. The effect of this new dual-treatment modality on HRQOL was evaluated separately [23]. During treatment and follow-up, both treatment-group changes over time, in seven preselected HRQOL domains, were not substantial during the first year of follow-up, provided there was no progression of disease. For several scales, scores even improved over time. However, during treatment, the patients in the combination treatment group reported more side effects (nausea, vomiting, appetite loss, and constipation) than those in the radiotherapy-only group, which can be attributed to the use of temozolomide and antiemetics. Overall, it can be concluded that the addition of temozolomide during and after radiotherapy produced a significantly longer survival time without a long-lasting negative effect on HRQOL. As for treatment in patients with anaplastic oligodendroglioma, adjuvant treatment with PCV chemotherapy after radiotherapy led to a significantly longer progression-free survival time but not overall survival time [51]. With respect to HRQOL, patients receiving PCV chemotherapy showed significantly more nausea/vomiting and appetite loss during and shortly following treatment than patients receiving only radiotherapy. Furthermore, patients on PCV reported more drowsiness. These differences, however, resolved over time: after 1 year of follow-up, differences were no longer observed in HRQOL between treatment groups [24]. Overall, there is a short-lasting negative impact of PCV chemotherapy on HRQOL during and shortly after treatment, but no long-term effects on HRQOL have been established. More importantly, because PCV chemotherapy postpones tumor progression, the impact of progression on well-being and HRQOL should be evaluated in future studies.

Patients with recurrent HGG successfully treated with temozolomide achieved a statistically significant improvement in a portion of the HRQOL domains, whereas patients with disease progression reported a statistically significant deterioration in most HRQOL domains [22, 52]. Therefore, HRQOL benefits from temozolomide treatment exist for the period of stable disease as a result of treatment before disease progression occurs. The effect of temozolomide on HRQOL in recurrent glioblastoma patients was compared with the effect of procarbazine in a randomized study. Patients receiving procarbazine showed deterioration in most HRQOL domains during treatment, whereas patients treated with temozolomide improved while on treatment [2]. Although temozolomide chemotherapy has largely replaced PCV chemotherapy in glioma patients, because of fewer side effects and better tolerability, HRQOL data on chemotherapy in elderly HGG patients with a poor performance status, as well as in the recurrent setting, are scarce [4].

Effect of Supportive Treatment on HRQOL

Symptomatic medications prescribed for glioma patients include antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and steroids (dexamethasone). Because the occurrence of seizures can diminish HRQOL, it could be assumed that treatment with AEDs improves quality of life. However, an adverse effect of AEDs on cognition has been demonstrated. The impact of seizures and AEDs on cognition and quality of life showed that both cognitive functions and HRQOL deteriorated in LGG patients. The cognitive deficits could primarily be ascribed to the use of AEDs, whereas the low HRQOL scores were mainly related to poor seizure control [32].

Dexamethasone reduces peritumoral edema and is prescribed to alleviate neurological symptoms, thereby improving quality of life. However, common side effects are myopathy, gastrointestinal complications, hyperglycemia, and psychiatric complications (mainly agitation or depression). Because these side effects are related to the prescribed dosage, steroids should be tapered or maintained at the lowest effective dose [53].

HRQOL in Clinical Practice

In daily practice, prognostic factors such as age and functional status are used to select brain tumor patients who will probably benefit from aggressive treatment and patients who will probably not. HRQOL parameters have been shown to be independent prognostic factors in various types of cancers [54]. At present, the prognostic value of baseline HRQOL data in predicting the survival duration of glioma patients is questionable. Two studies performed in HGG patients determined the prognostic significance of FACT scores. The first one demonstrated that patients with high scores on the FACT-G had longer survival times than patients with low scores [55]. The second one, using the FACT-Br in combination with a five-item linear analog scale assessment, also found a relation between high HRQOL scores and longer survival on univariate analysis. However, HRQOL was closely related to functional status, and after correction for this in a multivariate analysis, no prognostic significance of HRQOL scores remained [21]. Two EORTC brain tumor studies regarding this issue were analyzed by Mauer et al. [54, 56]. Classical analysis of EORTC QLQ-C30 subscores, controlled for major prognostic factors such as age and performance status, identified cognitive functioning, global health status, and social functioning as statistically significant prognostic factors for survival in glioblastoma patients. In patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, emotional functioning, communication deficit, future uncertainty, and weakness of legs were found to be significant prognostic factors [56]. In a boot-strap analysis, HRQOL scales were added to other predictive factors in a prognostic model and revealed that the HRQOL scales did not improve the prognostic value of known clinical factors. More importantly, fewer parameters are required in the prognostic model using clinical factors than in the model using HRQOL data. From these analyses, it can be concluded that, although various HRQOL scales have prognostic value they have no additional value over already known clinical factors.

However, in another respect, HRQOL data may have value in daily clinical practice. Routine HRQOL measurements of oncology patients visiting the outpatient department, with information provided to physicians, have been shown to have a positive effect on physician–patient communication. In some patients, these measurements improved HRQOL and emotional functioning. However, measurement of HRQOL, symptoms, and functioning is still far from being implemented in daily practice. In the future, a core set of standard and disease-specific questions repeated at key points in the disease trajectory (beginning of treatment, midtreatment, during follow-up, at relapse) should be implemented to allow comparison over time. A small set of focused HRQOL questions could be used at each visit (e.g., during treatment the focus could be on side effects). Furthermore, clear interpretation of scores is important and decision guidelines should be provided to clinicians [57].

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Martin J.B. Taphoorn, Andrew Bottomley

Provision of study material or patients: Martin J.B. Taphoorn, Eefje M. Sizoo

Collection and/or assembly of data: Martin J.B. Taphoorn, Andrew Bottomley, Eefje M. Sizoo

Data analysis and interpretation: Martin J.B. Taphoorn, Andrew Bottomley

Manuscript writing: Martin J.B. Taphoorn, Andrew Bottomley, Eefje M. Sizoo

Final approval of manuscript: Martin J.B. Taphoorn, Andrew Bottomley, Eefje M. Sizoo

References

- 1.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Population-based studies on incidence, survival rates, and genetic alterations in astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:479–489. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Efficace F, Bottomley A. Health related quality of life assessment methodology and reported outcomes in randomised controlled trials of primary brain cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1824–1831. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart MG, Grant R, Garside R, et al. Temozolomide for high grade glioma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD007415. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bottomley A, Flechtner H, Efficace F, et al. Health related quality of life outcomes in cancer clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1697–1709. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng JX, Zhang X, Liu BL. Health-related quality of life in patients with high-grade glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:41–50. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant R, Slattery J, Gregor A, et al. Recording neurological impairment in clinical trials of glioma. J Neurooncol. 1994;19:37–49. doi: 10.1007/BF01051047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spitzer WO, Dobson AJ, Hall J, et al. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: A concise QL-index for use by physicians. J Chronic Dis. 1981;34:585–597. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(81)90058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aaronson NK. Quality of life: What is it? How should it be measured? Oncology (Williston Park) 1988;2:69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taphoorn MJ, Claassens L, Aaronson NK, et al. An international validation study of the EORTC brain cancer module (EORTC QLQ-BN20) for assessing health-related quality of life and symptoms in brain cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weitzner MA, Meyers CA, Gelke CK, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) scale. Development of a brain subscale and revalidation of the general version (FACT-G) in patients with primary brain tumors. Cancer. 1995;75:1151–1161. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950301)75:5<1151::aid-cncr2820750515>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong TS, Mendoza T, Gring I, et al. Validation of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module (MDASI-BT) J Neurooncol. 2006;80:27–35. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong TS, Gring I, Mendoza TR, et al. Clinical utility of the MDASI-BT in patients with brain metastases. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sneeuw KC, Sprangers MA, Aaronson NK. The role of health care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality of life of patients with chronic disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:1130–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown PD, Decker PA, Rummans TA, et al. A prospective study of quality of life in adults with newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas: Comparison of patient and caregiver ratings of quality of life. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31:163–168. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318149f1d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker M, Brown J, Brown K, et al. Practical problems with the collection and interpretation of serial quality of life assessments in patients with malignant glioma. J Neurooncol. 2003;63:179–186. doi: 10.1023/a:1023900802254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taphoorn MJ, Klein M. Cognitive deficits in adult patients with brain tumours. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:159–168. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovagnoli AR, Silvani A, Colombo E, et al. Facets and determinants of quality of life in patients with recurrent high grade glioma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:562–568. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.036186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein M, Taphoorn MJ, Heimans JJ, et al. Neurobehavioral status and health-related quality of life in newly diagnosed high-grade glioma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4037–4047. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.20.4037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown PD, Ballman KV, Rummans TA, et al. Prospective study of quality of life in adults with newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2006;76:283–291. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-7020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osoba D, Brada M, Yung WK, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients treated with temozolomide versus procarbazine for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1481–1491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taphoorn MJ, Stupp R, Coens C, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with glioblastoma: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:937–944. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taphoorn MJ, van den Bent MJ, Mauer ME, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients treated for anaplastic oligodendroglioma with adjuvant chemotherapy: Results of a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5723–5730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackworth N, Fobair P, Prados MD. Quality of life self-reports from 200 brain tumor patients: Comparisons with Karnofsky performance scores. J Neurooncol. 1992;14:243–253. doi: 10.1007/BF00172600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sachsenheimer W, Piotrowski W, Bimmler T. Quality of life in patients with intracranial tumors on the basis of Karnofsky's performance status. J Neurooncol. 1992;13:177–181. doi: 10.1007/BF00172768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taphoorn MJ, Heimans JJ, Snoek FJ, et al. Assessment of quality of life in patients treated for low-grade glioma: A preliminary report. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:372–376. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.5.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taphoorn MJ, Schiphorst AK, Snoek FJ, et al. Cognitive functions and quality of life in patients with low-grade gliomas: The impact of radiotherapy. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:48–54. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reijneveld JC, Sitskoorn MM, Klein M, et al. Cognitive status and quality of life in patients with suspected versus proven low-grade gliomas. Neurology. 2001;56:618–623. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.5.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gustafsson M, Edvardsson T, Ahlström G. The relationship between function, quality of life and coping in patients with low-grade gliomas. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:1205–1212. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Struik K, Klein M, Heimans JJ, et al. Fatigue in low-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2009;92:73–78. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9738-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein M, Engelberts NH, van der Ploeg HM, et al. Epilepsy in low-grade gliomas: The impact on cognitive function and quality of life. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:514–520. doi: 10.1002/ana.10712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edvardsson TI, Ahlström GI. Subjective quality of life in persons with low-grade glioma and their next of kin. Int J Rehabil Res. 2009;32:64–70. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e32830bfa8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giovagnoli AR. Quality of life in patients with stable disease after surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy for malignant brain tumour. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:358–363. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.3.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salo J, Niemelä A, Joukamaa M, et al. Effect of brain tumour laterality on patients' perceived quality of life. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:373–377. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.3.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osoba D, Aaronson NK, Muller M, et al. Effect of neurological dysfunction on health-related quality of life in patients with high-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 1997;34:263–278. doi: 10.1023/a:1005790632126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta D, Lis CG, Grutsch JF. The relationship between cancer-related fatigue and patient satisfaction with quality of life in cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pelletier G, Verhoef MJ, Khatri N, et al. Quality of life in brain tumor patients: The relative contributions of depression, fatigue, emotional distress, and existential issues. J Neurooncol. 2002;57:41–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1015728825642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mainio A, Tuunanen S, Hakko H, et al. Decreased quality of life and depression as predictors for shorter survival among patients with low-grade gliomas: A follow-up from 1990 to 2003. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:516–521. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0674-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kvale EA, Murthy R, Taylor R, et al. Distress and health-related quality of life in primary high-grade brain tumor patients. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:793–799. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0551-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bosma I, Reijneveld JC, Douw L, et al. Health-related quality of life of long-term high-grade glioma survivors. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:51–58. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown PD, Maurer MJ, Rummans TA, et al. A prospective study of quality of life in adults with newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas: The impact of the extent of resection on quality of life and survival. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:495–504. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000170562.25335.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duffau H. A personal consecutive series of surgically treated 51 cases of insular WHO Grade II glioma: Advances and limitations. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:696–708. doi: 10.3171/2008.8.JNS08741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van den Bent MJ, Afra D, de Witte O, et al. Long-term efficacy of early versus delayed radiotherapy for low-grade astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma in adults: The EORTC 22845 randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:985–990. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiebert GM, Curran D, Aaronson NK, et al. Quality of life after radiation therapy of cerebral low-grade gliomas of the adult: Results of a randomised phase III trial on dose response (EORTC trial 22844). EORTC Radiotherapy Co-operative Group. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1902–1909. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klein M, Heimans JJ, Aaronson NK, et al. Effect of radiotherapy and other treatment-related factors on mid-term to long-term cognitive sequelae in low-grade gliomas: A comparative study. Lancet. 2002;360:1361–1368. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Douw L, Klein M, Fagel SS, et al. Cognitive and radiological effects of radiotherapy in patients with low-grade glioma: Long-term follow-up. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:810–818. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keime-Guibert F, Chinot O, Taillandier L, et al. Radiotherapy for glioblastoma in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1527–1535. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ernst-Stecken A, Ganslandt O, Lambrecht U, et al. Survival and quality of life after hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for recurrent malignant glioma. J Neurooncol. 2007;81:287–294. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu R, Solheim K, Polley MY, et al. Quality of life in low-grade glioma patients receiving temozolomide. Neuro-Oncology. 2009;11:59–68. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van den Bent MJ, Carpentier AF, Brandes AA, et al. Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine improves progression-free survival but not overall survival in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas: A randomized European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2715–2722. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osoba D, Brada M, Yung WK, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with anaplastic astrocytoma during treatment with temozolomide. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1788–1795. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaal EC, Vecht CJ. The management of brain edema in brain tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16:593–600. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000142076.52721.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mauer M, Stupp R, Taphoorn MJ, et al. The prognostic value of health-related quality-of-life data in predicting survival in glioblastoma cancer patients: Results from an international randomised phase III EORTC Brain Tumour and Radiation Oncology Groups, and NCIC Clinical Trials Group study. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:302–307. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sehlen S, Lenk M, Hollenhorst H, et al. Quality of life (QoL) as predictive mediator variable for survival in patients with intracerebral neoplasma during radiotherapy. Onkologie. 2003;26:38–43. doi: 10.1159/000069862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mauer ME, Taphoorn MJ, Bottomley A, et al. Prognostic value of health-related quality-of-life data in predicting survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, from a phase III EORTC brain cancer group study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5731–5737. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Velikova G, Awad N, Coles-Gale R, et al. The clinical value of quality of life assessment in oncology practice—a qualitative study of patient and physician views. Psychooncology. 2008;17:690–698. doi: 10.1002/pon.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]