Despite advances in the field, pancreatic cancer is one of the most aggressive and therapy-resistant types of cancer, with the lowest 5-year survival rate of all types of malignancies. There is an urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies and prognostic and predictive biomarkers to better treat this deadly disease. MMR gene variants may have potential value as prognostic markers for OS in pancreatic cancer patients.

Keywords: DNA mismatch repair, Pancreatic cancer, Single-nucleotide polymorphism, Survival

Abstract

Purpose.

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) maintains genomic stability and mediates cellular response to DNA damage. We aim to demonstrate whether MMR genetic variants affect overall survival (OS) in pancreatic cancer.

Materials and Methods.

Using the Sequenom method in genomic DNA, we retrospectively genotyped 102 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of 13 MMR genes from 706 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma seen at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Association between genotype and OS was evaluated using multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models.

Results.

At a false discovery rate of 1% (p ≤ .0015), 15 SNPs of EXO1, MLH1, MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, PMS2, PMS2L3, TP73, and TREX1 in patients with localized disease (n = 333) and 6 SNPs of MSH3, MSH6, and TP73 in patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease (n = 373) were significantly associated with OS. In multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models, SNPs of EXO1, MSH2, MSH3, PMS2L3, and TP73 in patients with localized disease, MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, and TP73 in patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease, and EXO1, MGMT, MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, PMS2L3, and TP73 in all patients remained significant predictors for OS (p ≤ .0015) after adjusting for all clinical predictors and all SNPs with p ≤ .0015 in single-locus analysis. Sixteen haplotypes of EXO1, MLH1, MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, PMS2, PMS2L3, RECQL, TP73, and TREX1 significantly correlated with OS in all patients (p ≤ .001).

Conclusion.

MMR gene variants may have potential value as prognostic markers for OS in pancreatic cancer patients.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States [1]. Despite advances in the field, pancreatic cancer is one of the most aggressive and therapy-resistant types of cancer, with the lowest 5-year survival rate of all types of malignancies [1]. There is an urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies and prognostic and predictive biomarkers to better treat this deadly disease.

We have shown previously that genetic variations in drug metabolism and DNA repair correlate with overall survival (OS) of patients with pancreatic cancer [2–5]. However, most of our studies were limited by small sample sizes, small numbers of genes examined, and lack of validation and unknown functional significance of the genetic variants [2–5]. Thus, the potential value of our previous findings in clinical application is not yet known. To confirm and expand on our previous findings, our current study focused on one of the most important DNA repair pathways, mismatch repair (MMR), in a large cohort of 706 patients with pancreatic cancer.

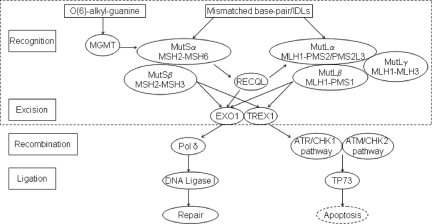

MMR is critical to maintaining genome stability [6]. An MMR deficiency may confer genome-wide instability and contribute to aggressive tumor phenotypes by accumulating genetic alterations [6]. We evaluated 13 genes (Fig. 1), which encode core components involved in the DNA mismatch recognition and removal such as mutS homolog 2 (MSH2), MSH3, MSH6, mutL homolog 1 (MLH1), MLH3, postmeiotic segregation increased 1 (PMS1), PMS2, PMS2-like 3 (PMS2L3), exonuclease I (EXO1), three prime repair exonuclease 1 (TREX1), and O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) and MMR regulators such as RecQ protein-like/DNA helicase Q1-like (RECQL) or MMR-induced apoptosis transducer such as tumor protein 73 (TP73) [7, 8].

Figure 1.

Selected gene-encoded proteins involved in human mismatch repair (MMR) system. MMR machinery consists of human homologs of MutSα, MutSβ, MutLα, MutLβ, MutLγ, exonuclease (EXO1, TREX1), DNA polymerase δ (Pol δ), and DNA ligase I [9, 11]. The mismatch-bound MutSα or MutSβ recruited MutLα (MutLβ/MutLγ). The ternary complex activated EXO1 and TREX1 to commence the degradation of the strand in a 5′→3′ direction. Pol δ filled the gap, and DNA ligase I sealed the remaining nick to complete the repair process. MMR eliminated damaged cells via apoptosis network. MutS/MutL/exonuclease can transduce DNA damage signaling to the cell-cycle checkpoint machinery ataxia-telangiectasia mutated and rad3-related (ATR)/checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) or ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)/checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) directly, which leads to cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis [8, 12]. CHK1 and CHK2 regulate TP73 induction to initiate p53-independent apoptosis [7]. MGMT repairs the O(6)-alkyl-guanine mismatches dependent on MutSα/MutLα/EXO1 [13, 14]. MutSα stimulates RECQL helicase activity; RECQL stimulates EXO1 incision activity and interacts with MLH1 [16].

The proteins encoded by the genes examined in this study play various roles in the MMR process. Human MutSα homolog (MSH2/MSH6) recognizes base-base mismatches and small insertion/deletion loops (IDLs) [6, 9]. The MutSβ homolog MSH2/MSH3 also recognizes IDLs [6, 9]. MutLα homolog MLH1/PMS2 forms a ternary complex with mismatched DNA and MutSα, increases discrimination between heteroduplexes and homoduplexes, and functions in meiotic recombination [6]. Cells deficient in either MutL or MutS homologs, for example, MLH1 and MSH2, exhibit mutator phenotype and microsatellite instability [6]. PMS2L3, a member of the PMS2 family, contains motifs (e.g., KELVEN) that are conserved among MutL proteins [10]. PMS2L3 encodes a polypeptide similar to PMS2 in exons 2–3 due to frame shift caused by a 10-nucleotide insertion [10]. PMS2L3 codons 180–255 are 97% identical to PMS2 [10]. The MutLβ homolog MLH1/PMS1 and the MutLγ homolog MLH1/MLH3 primarily function in meiotic recombination and serve as a backup mechanism for MutLα in repairing base-base mismatches/small IDLs [6]. EXO1 encodes 5′-3′ exonuclease which is involved in MMR and recombination by interacting with MSH2 [9, 11]. TREX1 encodes 3′-5′ DNA exonuclease that proofreads for DNA polymerase and degrades 3′ ends of nicked DNA in granzyme A–mediated cell death [12]. MGMT plays a crucial role in the defense against alkylating agents by interacting with MutSα, MutLα, and EXO1 [13, 14]. MGMT downregulation activates p53 and inhibits pancreatic cancer tumor growth [15]. RECQL is a member of the RecQ DNA helicase family that is required for DNA replication, recombination, and repair [16, 17]. TP73, a member of the p53 family, is involved in cellular responses to stress and development [18]. MMR-mediated p53-independent apoptosis is stimulated by MLH1/c-Abl/p73α/GADD45α retrograde signaling [19].

In the current study, we examined 102 single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the above-mentioned 13 MMR genes in 706 patients with pancreatic cancer and demonstrated their associations with overall survival. Our previous findings on the associations of some of the MMR genes including RECQL with the clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer [2–4] are confirmed in this larger data set and new findings on additional genes are also reported.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population and Clinical Data

The 706 patients involved in this study include 154 patients with potentially resectable tumors who had been enrolled in phase II clinical trials for preoperative chemoradiation [4] and 552 patients who had been recruited to a case-control study of pancreatic cancer conducted at MD Anderson during February 1999 through May 2007. The patient inclusion criteria are (1) having been diagnosed with a pathologically confirmed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and (2) having a blood or tissue sample for DNA extraction. Each patient had signed an informed consent for medical record review and DNA sample donation. The institutional review board at MD Anderson Cancer Center had approved the previous studies, which had been conducted according to all current ethical guidelines.

We reviewed the 706 patients' medical records and extracted the following types of clinical information: dates of diagnosis and death or last follow-up; tumor stage, resection status, differentiation, size, and site; performance status; and serum markers for liver, kidney, and pancreas functions as well as serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) level at diagnosis. Clinical tumor staging at the time of diagnosis had followed the objective computed tomography (CT) criteria: a localized or potentially resectable tumor had been defined as a tumor (1) without evidence of extrapancreatic disease (extensive peripancreatic lymph node involvement), (2) without invasion of the celiac axis or superior mesenteric artery, inferior vena cava, or aorta, or (3) without encasement or occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein–portal vein confluence [20]. Tumor that abutted and encased the superior mesenteric vein, without vessel occlusion or extension to the superior mesenteric artery, had been considered resectable [20]. Locally advanced tumors had been defined as those that were unresectable but without distant metastasis. Tumor margin and lymph node status had been evaluated only in patients with resected tumors. Dates of death were obtained from the MD Anderson Cancer Center Tumor Registry, inpatient electronic medical records, or the United States Social Security Death Index (www.deathindexes.com/ssdi.html).

DNA Extraction, Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Selection, and Genotyping

For this retrospective study, DNA samples of 706 patients for genotyping were available from the original studies [4, 21]. Using Qiagen DNA isolation kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), we extracted DNA from archived peripheral blood lymphocytes samples of 679 patients. Blood samples were not collected in 27 patients with resected tumors so archived paraffin sections of normal tissues adjacent to tumors were used for DNA extraction in these patients. Tissue sections were obtained from our Institutional Tissue Bank and normal tissues were identified by certified pathologists. Normal and tumor tissues were expected to have the same genotype for these germline common polymorphic sequence variants. We selected 45 tagging SNPs using the SNPbrowser (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) with a cutoff of r2 = 0.8 and a MAF ≥10% in White from the HapMap Project database (www.hapmap.org). For more comprehensive coverage of the gene variants, we included 57 SNPs in the coding region (nonsynonymous or synonymous), untranslated region (UTR), promoter region, or splicing sites that have a MAF ≥1% in White. The genes, nucleotide substitutions, functions (such as encoding amino acid changes), reference SNP identification numbers, and reported allele frequencies of the 102 SNPs evaluated in this study are summarized in supplemental online Table 1. The protein sequences, structures, homology models, mRNA transcripts, and predicted functions for the SNPs were evaluated using F-SNP software (Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada) [22]. For genotyping, we used the mass spectroscopy–based MassArray method (Sequenom, Inc., San Diego). Twenty percent of the DNA samples were genotyped in duplicate, with 99.6% concordance. Inconsistent genotyping calling data were excluded from our final analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We examined the distribution of genotypes for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium using the goodness-of-fit χ2 test. We calculated genotype frequency and allele frequency of the SNPs by direct gene counting. We calculated haplotype diversity and linkage disequilibrium index (Lewontin′s |D′| and r2) using SNPAlyze (DYNACOM Co., Ltd. Mobara, Japan). Haplotypes were reconstructed by implementing the EM algorithm using the unphased genotype data in the three major ethnic/racial groups, that is, non-Hispanic white, Hispanics, and blacks. We computed the median follow-up time using censored observations only. We estimated the effect of genotype/haplotype on OS using Cox proportional hazards regression model. We calculated hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) in the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model with adjustments for sex, age, race, and any significant clinical predictors for OS. OS was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up.

Genotypes were combined in some analyses. The homozygous and heterozygous variants were combined if (1) the homozygous variant was present in ≤5 patients and (2) if the genotype effect on survival is dominant, that is, both the heterozygote and homozygote had p < .05 in log-rank test compared to the wild type. The heterozygote was combined with the wild type if the genotype effect was recessive; that is, only the homozygote was significantly different from the wild type in survival. We performed statistical testing using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago) and Stata (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). We calculated the Harrell's C index (concordance) to test the proportional-hazards assumption. We calculated the false discovery rate (FDR) using the beta-uniform mixture method [23]. For 200 comparisons in 102 SNPs for OS in 706 patients, we found that p-values of .0015 and .028 corresponded with FDRs of 1% and 5%, respectively. For the genotype analysis in our study, p ≤ .0015 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients' Characteristics

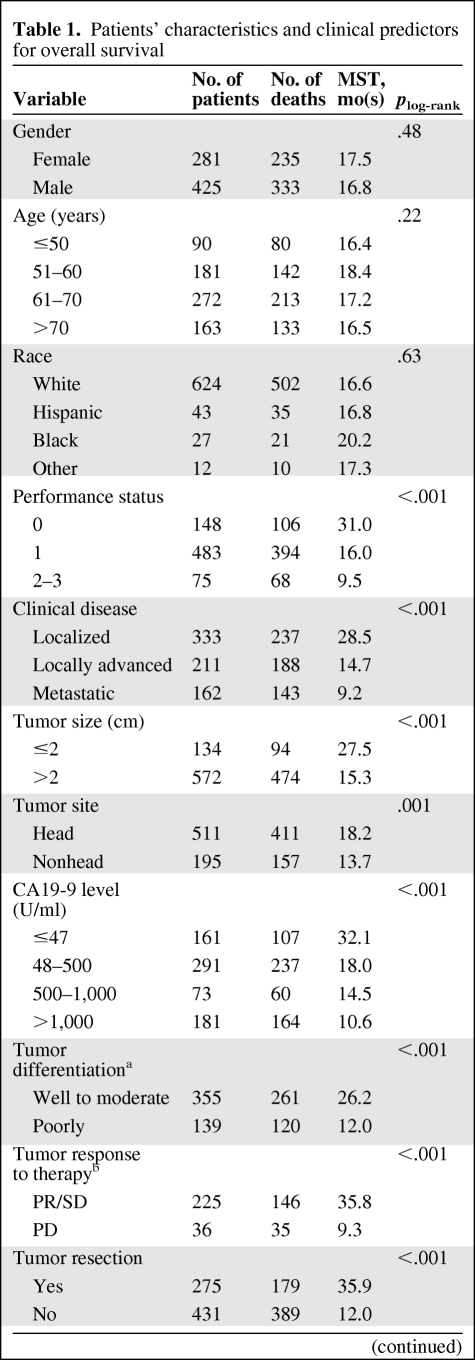

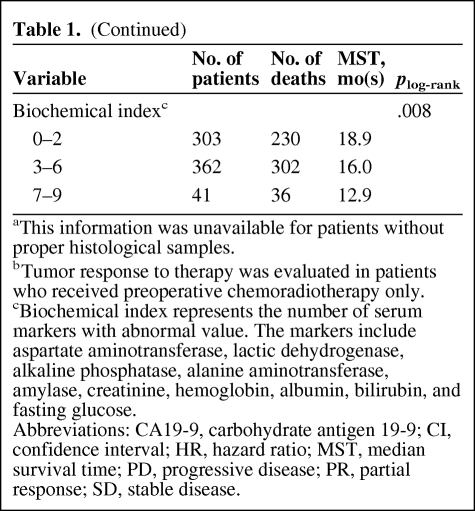

The patients' characteristics and clinical predictors of OS for the study patients are described in Table 1. The 706 patients included 333 (154 on and 179 off clinical trials) with localized disease, 211 with locally advanced disease, and 162 with metastatic disease. Of the 333 patients with localized tumors, 275 (83%) had undergone tumor resection. Of the 706 patients, 138 (19.5%) were still alive at the end of the original study period, with a median follow-up time of 46.0 months. The median survival duration (MSD) for the entire patient population was 17.2 months (95% CI, 15.8–18.5). Advanced tumor stage, unresected tumor, an elevated CA19-9 serum level or biochemical index, or poor performance status were significant predictors for poor OS in multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model (data not shown).

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics and clinical predictors for overall survival

Table 1.

(Continued)

aThis information was unavailable for patients without proper histological samples.

bTumor response to therapy was evaluated in patients who received preoperative chemoradiotherapy only.

cBiochemical index represents the number of serum markers with abnormal value. The markers include aspartate aminotransferase, lactic dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, amylase, creatinine, hemoglobin, albumin, bilirubin, and fasting glucose.

Abbreviations: CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MST, median survival time; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Genotype Distribution and Allele Frequencies

The observed minor allele frequencies of the 102 tested SNPs in our study population were comparable with those reported in the general population (supplemental online Table 1). Linkage disequilibrium data of the 102 SNPs in the entire study population and in non-Hispanic whites are summarized in supplemental online Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Most of the 102 tested SNPs followed the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), except for MGMT IVS4-44836G>A (p < .001), MLH1 I219V (p = .003), MLH3 P844L (p = .0054), MSH2 IVS1+9A>T (p = .0035), IVS9-9A>T (p < .001), IVS11-62G>A (p < .001), PMS2 P470S (p < .001), N775S (p < .001), PMS2L3 IVS3+9A>G (p < .001), RECQL IVS11+218T>G (p = .0013), IVS8+190A>G (p < .001), and IVS4-795C>T (p = .002).

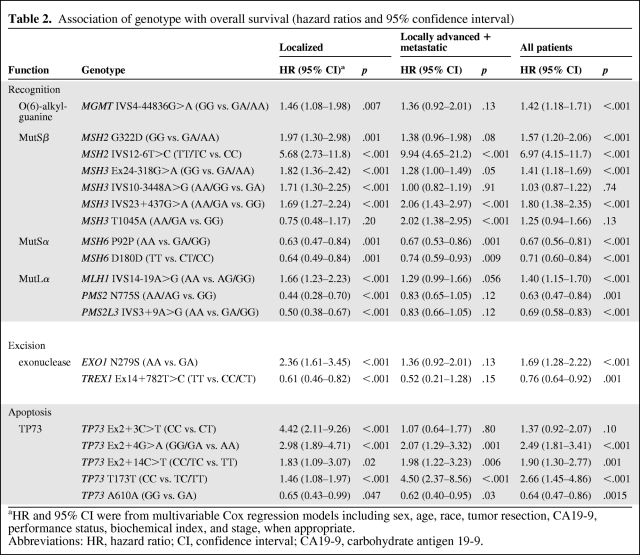

Associations of Genotype with Overall Survival

First, we analyzed genotype association with OS in 333 patients with localized disease and 373 patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease separately. Fifteen SNPs of nine genes (i.e., EXO1, MLH1, MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, PMS2, PMS2L3, TP73, and TREX1) were significantly associated with OS at 1% FDR level (p ≤ .0015) after adjustment for clinical factors in patients with localized disease (Table 2). Six SNPs of MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, and TP73 were significantly associated with OS in patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease. When data of the 706 patients were pooled to increase power, 16 SNPs were significantly associated with OS. The Harrell's C indexes (concordance) were all >0.61, indicating the data did not violate the proportionality assumption (data not shown). To reduce population stratification bias, we performed additional data analysis in non-Hispanic only and the results are quite comparable to those in the entire study population. None of the risk estimates had >10% differences between the two study populations (supplemental online Table 4). Thus, data from the entire study population are presented in this report.

Table 2.

Association of genotype with overall survival (hazard ratios and 95% confidence interval)

aHR and 95% CI were from multivariable Cox regression models including sex, age, race, tumor resection, CA19-9, performance status, biochemical index, and stage, when appropriate.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

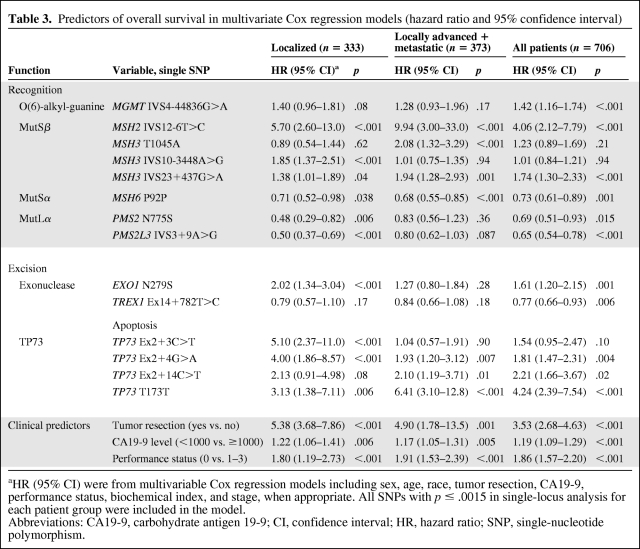

Next, we conducted multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, including all the SNPs that reached 1% FDR level and all significant clinical predictors. EXO1, MSH2, MSH3, PMS2L3, and TP73 in patients with localized disease; MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, and TP73 in patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease; and EXO1, MGMT, MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, PMS2L3, and TP73 in all patients remained significant predictors (Table 3). Results from the same analyses conducted in non-Hispanic whites are summarized in supplemental online Table 5.

Table 3.

Predictors of overall survival in multivariate Cox regression models (hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval)

aHR (95% CI) were from multivariable Cox regression models including sex, age, race, tumor resection, CA19-9, performance status, biochemical index, and stage, when appropriate. All SNPs with p ≤ .0015 in single-locus analysis for each patient group were included in the model.

Abbreviations: CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

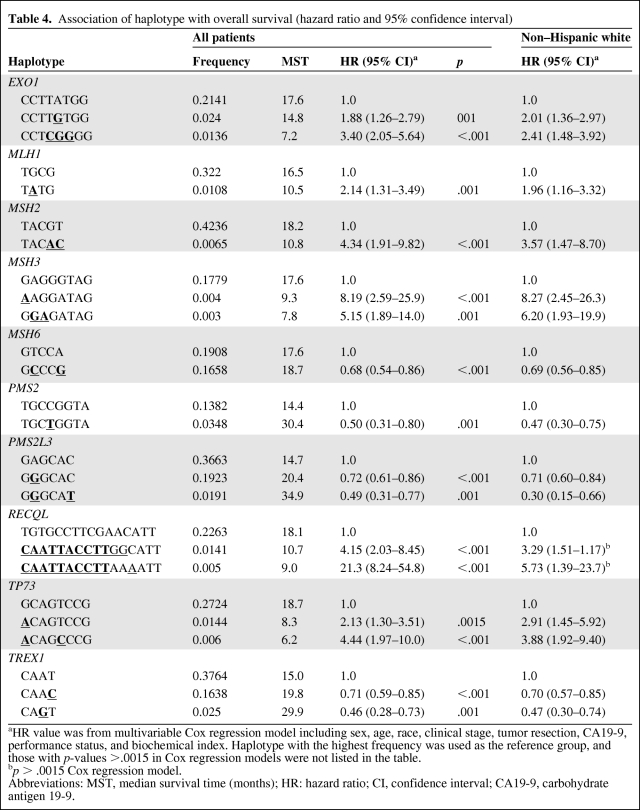

Associations of Haplotype Diversity with OS

Haplotype distribution in different ethnic/racial groups is presented in supplemental online Table 6. Because of the large variation in haplotype distribution between ethnic/racial groups and the small number of minorities, haplotype associations with OS were analyzed in non-Hispanic whites as well as in the entire study population with justification for race (Table 4). Sixteen haplotypes of EXO1, MLH1, MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, PMS2, PMS2L3, RECQL, TP73, and TREX1 genes were significantly associated with OS (p ≤ .0015). The associations of haplotypes with OS manifested the effects of EXO1 N279S GA; MLH1-92G>A AA; MSH2 IVS11-62G>A GA/AA and -117T>C CT/CC; MSH3 P231P AA, T1045A GG, and Q949R GA/AA; MSH6 D180D CT/CC and P92P GA/GG; PMS2 IVS1-1121C>T TC/TT; PMS2L3 IVS3+9A>G GA/GG and IVS1-8C>T CT; CAATTACCTT of RECQL IVS2+1222T>C, *1236A>G, IVS11+582T>A, IVS11+218T>G, IVS6–1031T>C, IVS5-717C>A, IVS4-795C>T, IVS4+1179T>C, IVS1-92C>T, and IVS1–570T>G; TP73 Ex2+4G>A AA and *1454C>T CC; TREX1 Ex14+297A>G AG and Ex14+782T>C CT/CC genotypes. Although none of the individual SNPs reached the 1% FDR significance level for RECQL, the haplotype CAATTACCTT did reach that level (p < .001) when all study participants were included in the analysis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association of haplotype with overall survival (hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval)

aHR value was from multivariable Cox regression model including sex, age, race, clinical stage, tumor resection, CA19-9, performance status, and biochemical index. Haplotype with the highest frequency was used as the reference group, and those with p-values >.0015 in Cox regression models were not listed in the table.

bp > .0015 Cox regression model.

Abbreviations: MST, median survival time (months); HR: hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Discussion

Results from the current study confirmed our previous observations of an association between MMR gene variants and OS in pancreatic cancer. At the FDR level of 1%, 10 of the 102 tested SNPs from 7 of the 13 MMR genes examined (i.e., EXO1, MGMT, MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, PMS2L3, and TP73) were significant independent predictors for OS in multi-SNP Cox proportional hazards regression models with adjustment for clinical predictors. These findings support a role for MMR polymorphisms in modifying the tumor phenotype and clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer.

MMR is a complicated network with multiple functions, one being to maintain genome stability by removing mismatched or distorted DNA structures [6]. However, MMR also plays an important role in apoptosis signaling when cells are overwhelmed with genotoxic insults [6]. Thus, MMR deficiency contributes to both genomic instability and altered DNA damage response [6]. As MMR machinery is crucial in maintaining genomic stability, our finding indicates that dysfunctional MMR may contribute to rapid tumor progression via accumulated DNA damage and failed activation of apoptosis signaling pathways.

Although MMR deficiency has not been recognized as a major genetic alteration in pancreatic tumors [24], individuals with hereditary Lynch syndrome (an autosomal dominant genetic disorder caused by germline mutations in MMR genes) also have increased risk of pancreatic cancer [25]. The strong associations between MMR genetic variation and OS observed in our study add supporting evidence to the role of DNA MMR deficiency in pancreatic cancer progression.

We found that genetic variations in EXO1, MGMT, MLH1, MSH2, MSH3, PMS2, PMS2L3, and TREX1 correlated with OS mainly in patients with localized disease; MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, and TP73 correlated with OS mainly in those with locally advanced or metastatic disease; and MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, and TP73 correlated with OS in all patients. Although some of the inconsistent observations between patients with different stages of diseases may suggest false positive findings, our previous observation on the association between EXO1, MSH2, MSH3, and TP73 SNPs with OS in patients with resectable tumors [4] were confirmed in this larger patient population that was under stringent FDR control. In addition, we also observed a significant association between PMS2L3 IVS3+9A>G and OS in the current study. This intronic SNP is in linkage with a 3′UTR SNP Ex7-32G>A. Bioinformatics has predicted that the latter SNP may confer a protein with altered solvent accessibility [22]. PMS2L3 has a similar function to that of PMS2 in MutLα, which is to play a role in maintaining genome integrity via MMR and DNA damage-induced apoptosis [26].

Loss of MSH3 protein expression has been related to tumor progression in colorectal cancer [27]. Our finding that the MSH3 genetic variants contributed to shorter OS in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer suggests that MSH3 deficiency may contribute to rapid tumor progression, possibly through accumulation of larger IDLs in patients with late-stage disease.

P73 is a homolog of the tumor suppressor gene p53, but its function in tumor development has not been established [28]. P73 plays an important role in apoptosis and chemosensitivity; thus, it has been recognized as a potential therapeutic target in cancer treatment [29]. Our findings on the association between P73 SNPs and OS support a role for this protein in pancreatic cancer progression.

We found RECQL haplotype was related to shorter OS in the 706 patients with pancreatic cancer. RECQL is a member of the RECQ DNA helicase family that is required for DNA replication, recombination, and repair [30]. Germline mutations of three of the five members of this protein family have been associated with hereditary syndromes characterized with chromosome instability, premature aging, and cancer susceptibility [30]. Although RECQL has not been associated with any hereditary syndromes, accumulating evidence suggests that RECQL is a regulating gene not only for the MMR network but also for cell cycle checkpoints [31]. RECQL might be a potential therapeutic target in cancer treatment [32].

In our current study, we found several nonsynonymous SNPs (e.g., MLH1 I219V, MSH3 T1045A, PMS2 N775S, EXO1 N279S, and TREX1 K125Q) and synonymous SNPs (e.g., MSH6 P92P and D180D; TP73 T173T and A610A) to be significantly associated with OS. Although the synonymous SNPs do not lead to amino acid change, some experimental evidence suggests that they could affect protein function [33]. In addition, some 5′UTR SNPs (e.g., TP73 Ex2+3C>T, Ex2+4G>A, and Ex2+14C>T) have been implicated in protein function modulation. These SNPs may cause frame-shift coding and alternative splicing, or they may affect transcription factor binding [34].

Furthermore, several 3′UTR SNPs (e.g., MSH3 Ex24-318G>A, TREX1 Ex14+297A>G, and Ex14+782T>C) in our study were also associated with OS. The 3′UTR SNPs may contain sequence motifs crucial for regulating transcription, mRNA stability, and cellular localization of the mRNA or microRNA binding [35]. A few tagging SNPs in our study (e.g. MLH1 IVS14-19A>G, MSH3 IVS10-3448A>G, and IVS23+437G>A) were associated with OS, and they are linked with the nonsynonymous SNP MLH1 I219V and MSH3 T1045A. As expected, the minor allele frequencies of the functional SNPs were relatively low, and thus a large sample size was required to demonstrate their phenotypic significance in a human study. Although some tagging SNPs might not be functional, they might be in linkage disequilibrium with other functional variants that are not measured in the current study. Larger studies covering functional SNPs with MAF <5% would be required to fully identify the responsible genetic variants.

The strengths of our study include a large sample size, detailed clinical information, a focused DNA repair pathway in gene selection, and comprehensive SNP coverage. The limitations of our study include the heterogeneous patient population, the potential false-positive findings related to multiple comparisons, and the lack of consideration of treatment effect. To overcome some of these limitations, we conducted data analyses stratified by disease stage and then applied a stringent FDR control p-value. Since it is well known that most treatment regimens do not make a significant impact on OS of patients with pancreatic cancer, we adjusted for almost all known clinical predictors in the Cox proportional hazards regression models.

The SNPs that significantly deviated from the HWE might indicate the following: (1) There are genotyping errors; (2) there are selection bias in patient recruitment; and (3) the variant allele of these SNPs might be associated with risk of pancreatic cancer, so they are either over- or under-represented in the cancer patients compared with the general population. Three SNPs, that is, MGMT IVS4-44836G>A, PMS2 N775S, and PMS2L3 IVS3+9A>G, that are not in HWE were significantly associated with OS. Although these associations could be false positive, the major results on other SNPs that followed the HWE are unlikely biased by the three SNPs.

Our results identifying the strong association between MMR gene variants and OS support a role for DNA MMR deficiency in pancreatic cancer progression. Because tissue samples are extremely hard to obtain from most patients with pancreatic cancer, genetic markers that are measurable in peripheral blood DNA are clinically preferred and valuable. Additional studies are warranted to establish and validate a genetic risk-prediction model for pancreatic cancer. Such studies could identify some genes as potential therapeutic targets in the treatment of this deadly disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 grant CA098380 (to D.L.), SPORE P20 grant CA101936 (to J.L.A.), NIH Cancer Center Core grant CA16672, and a research grant from the Lockton Research Funds (to D.L.).

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Donghui Li, Yanan Li

Provision of study material or patients: Donghui Li, James L. Abbruzzese

Collection and/or assembly of data: Xiaoqun Dong, Yanan Li

Data analysis and interpretation: Donghui Li, Xiaoqun Dong, Kenneth R. Hess

Manuscript writing: Donghui Li, Xiaoqun Dong

Final approval of manuscript: Donghui Li, James L. Abbruzzese

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li D, Frazier M, Evans DB, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of RecQ1, RAD54L, and ATM genes are associated with reduced survival of pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1720–1728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li D, Liu H, Jiao L, et al. Significant effect of homologous recombination DNA repair gene polymorphisms on pancreatic cancer survival. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3323–3330. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong X, Jiao L, Li Y, et al. Significant associations of mismatch repair gene polymorphisms with clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1592–1529. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okazaki T, Javle M, Tanaka M, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of gemcitabine metabolic genes and pancreatic cancer survival and drug toxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:320–329. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiricny J. The multifaceted mismatch-repair system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:335–346. doi: 10.1038/nrm1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urist M, Tanaka T, Poyurovsky MV, et al. p73 induction after DNA damage is regulated by checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Chk2. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3041–3054. doi: 10.1101/gad.1221004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan MA, Parsels LA, Parsels JD, et al. Role of checkpoint kinase 1 in preventing premature mitosis in response to gemcitabine. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6835–6842. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Constantin N, Dzantiev L, Kadyrov FA, et al. Human mismatch repair: reconstitution of a nick-directed bidirectional reaction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39752–39761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509701200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolaides NC, Carter KC, Shell BK, et al. Genomic organization of the human PMS2 gene family. Genomics. 1995;30:195–206. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Yuan F, Presnell SR, et al. Reconstitution of 5′-directed human mismatch repair in a purified system. Cell. 2005;122:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang YG, Lindahl T, Barnes DE. Trex1 exonuclease degrades ssDNA to prevent chronic checkpoint activation and autoimmune disease. Cell. 2007;131:873–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klapacz J, Meira LB, Luchetti DG, et al. O6-methylguanine-induced cell death involves exonuclease 1 as well as DNA mismatch recognition in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:576–581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811991106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaina B, Christmann M, Naumann S, et al. MGMT: key node in the battle against genotoxicity, carcinogenicity and apoptosis induced by alkylating agents. DNA Repair. 2007;6:1079–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konduri SD, Ticku J, Bobustuc GC, et al. Blockade of MGMT expression by O6 benzyl guanine leads to inhibition of pancreatic cancer growth and induction of apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6087–6095. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doherty KM, Sharma S, Uzdilla LA, et al. RECQ1 helicase interacts with human mismatch repair factors that regulate genetic recombination. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28085–28094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma S, Stumpo DJ, Balajee AS, et al. RECQL, a member of the RecQ family of DNA helicases, suppresses chromosomal instability. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1784–1794. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01620-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stiewe T. The p53 family in differentiation and tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:165–168. doi: 10.1038/nrc2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li LS, Morales JC, Hwang A, et al. DNA mismatch repair-dependent activation of c-Abl/p73alpha/GADD45alpha-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21394–21403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709954200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans DB, Varadhachary GR, Crane CH, et al. Preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiation for patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3496–3502. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li D, Suzuki H, Liu B, et al. DNA repair gene polymorphisms and risk of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:740–746. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee PH, Shatkay H. F-SNP: computationally predicted functional SNPs for disease association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D820–D824. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pounds S, Cheng C. Improving false discovery rate estimation. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1737–1745. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–1806. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kastrinos F, Mukherjee B, Tayob N, et al. Risk of pancreatic cancer in families with Lynch syndrome. JAMA. 2009;302:1790–1795. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo Y, Lin FT, Lin WC. ATM-mediated stabilization of hMutL DNA mismatch repair proteins augments p53 activation during DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6430–6444. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6430-6444.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plaschke J, Kruger S, Jeske B, et al. Loss of MSH3 protein expression is frequent in MLH1-deficient colorectal cancer and is associated with disease progression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:864–870. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melino G, De Laurenzi V, Vousden KH. p73: Friend or foe in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:605–615. doi: 10.1038/nrc861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lunghi P, Costanzo A, Mazzera L, et al. The p53 family protein p73 provides new insights into cancer chemosensitivity and targeting. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6495–6502. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khakhar RR, Cobb JA, Bjergbaek L, et al. RecQ helicases: multiple roles in genome maintenance. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:493–501. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y, Brosh RM., Jr Distinct roles of RECQ1 in the maintenance of genomic stability. DNA Repair. 2010;9:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta R, Brosh RM., Jr DNA repair helicases as targets for anti-cancer therapy. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:503–517. doi: 10.2174/092986707780059706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Oh JM, Kim IW, et al. A “silent” polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity. Science. 2007;315:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1135308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pickering BM, Willis AE. The implications of structured 5′ untranslated regions on translation and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazumder B, Seshadri V, Fox PL. Translational control by the 3′-UTR: the ends specify the means. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:91–98. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.