Gene expression analyses and loss of heterozygosity studies were performed to find new markers relevant to predict meningioma recurrence risk. The differential expression (C-L index) of CKS2 and LEPR was significantly higher in grade I than in grade II or III meningiomas, suggesting that the C-L index may be relevant to define progression risk.

Keywords: Meningiomas, DNA microarray, Loss of heterozygosity, Leptin receptor, Cyclin kinase

Abstract

Meningiomas are the most frequent intracranial tumors. Surgery can be curative, but recurrences are possible. We performed gene expression analyses and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) studies looking for new markers predicting the recurrence risk. We analyzed expression profiles of 23 meningiomas (10 grade I, 10 grade II, and 3 grade III) and validated the data using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). We performed LOH analysis on 40 meningiomas, investigating chromosomal regions on 1p, 9p, 10q, 14q, and 22q. We found 233 and 268 probe sets to be significantly down- and upregulated, respectively, in grade II or III meningiomas. Genes downregulated in high-grade meningiomas were overrepresented on chromosomes 1, 6, 9, 10, and 14. Based on functional enrichment analysis, we selected LIM domain and actin binding 1 (LIMA1), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 3 (TIMP3), cyclin-dependent kinases regulatory subunit 2 (CKS2), leptin receptor (LEPR), and baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis repeat-containing 5 (BIRC5) for validation using qPCR and confirmed their differential expression in the two groups of tumors. We calculated ΔCt values of CKS2 and LEPR and found that their differential expression (C-L index) was significantly higher in grade I than in grade II or III meningiomas (p < .0001). Interestingly, the C-L index of nine grade I meningiomas from patients who relapsed in <5 years was significantly lower than in grade I meningiomas from patients who did not relapse. These findings indicate that the C-L index may be relevant to define the progression risk in meningioma patients, helping guide their clinical management. A prospective analysis on a larger number of cases is warranted.

Introduction

Meningiomas arise from meningothelial cells of the arachnoid layer and recent data have contributed to the identification of a common cell of origin for these tumors [1]. They account for 30% of all primary brain tumors, with an incidence of about five per 100,000 individuals [2]. Recent data, however, suggest that meningiomas may be more frequent in the asymptomatic population, with rates of 1.1% in females and 0.7% in males [3]. The higher frequency of meningiomas in females suggests a role for hormones in their development, and recent data seem to confirm such an association [4]. Nearly 80%–90% of meningiomas are benign, World Health Organization (WHO) grade I tumors, but display a broad spectrum of histological variants, the most frequent of which are meningothelial, fibrous, and transitional meningiomas [5]. WHO grade II meningiomas (15%–20% of meningiomas) include atypical, papillary, and rhabdoid meningiomas. WHO grade III meningiomas (anaplastic meningiomas) account for 1%–3% of all cases. Some anaplastic meningiomas are difficult to identify as meningothelial neoplasms because they can resemble sarcomas, carcinomas, or melanomas. Brain invasion is an important criterion in the 2007 WHO classification of atypical meningioma. Apparent diffusion coefficient values on magnetic resonance imaging scans observed with grade II and grade III meningiomas are significantly lower than with benign tumors. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography may also predict tumor grade and tumor recurrence [6].

In current clinical practice, surgery is the treatment of choice for patients with meningiomas, and the recurrence rates 5 years after gross total resection are 5% for patients with WHO grade I, 40% for patients with WHO grade II, and up to 80% for patients with WHO grade III meningiomas [7]. Radiotherapy is an accepted standard of care for patients with atypical and anaplastic meningiomas. Conventional chemotherapy has demonstrated marginal efficacy [8–10].

Several studies have pointed to involvement of the neurofibromin 2 (NF2) gene in meningioma formation: Multiple meningiomas are reported in NF2 patients, monosomy of 22q is the most common genetic alteration in meningiomas, and NF2 is mutated in about half of meningioma patients [11, 12], more frequently in fibrous or transitional meningiomas [13]. Merlin, the NF2 gene product, belongs to the 4.1 family of structural proteins that associate integral membrane proteins with the cytoskeleton [14]. Other proteins of the 4.1 family, such as differentially expressed in adenocarcinoma of the lung (DAL)-1, and tumor suppressor in lung cancer 1, a protein closely interacting with DAL-1, are downregulated in meningiomas. Moreover, overexpression of 4.1R inhibits cell growth in meningioma cell lines [15, 16].

During meningioma progression, a number of genomic alterations have been observed. Loss of 1p, 9p, 10q, and 14q are more frequent in higher-grade meningiomas [17]. Despite the large amount of data on meningiomas, clinical implications for patient management and follow-up are modest. Here, we report on expression profiling and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) studies on meningiomas of different grades, and on the identification of two marker genes that may help to identify grade I meningiomas with a tendency to recur.

Methods

Human Specimens

Seventy-six tumor specimens were collected in the departments of neurosurgery of the I.R.C.C.S. Istituto Neurologico C. Besta and the Istituti Ospitalieri of Cremona between 1995 and 2008. Corresponding blood samples were available for 40 patients. All patients gave their informed consent to the use of biological material for genetic studies. Resected meningiomas were partially snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80°C and partially paraffin embedded for the diagnosis. All samples were histologically classified according to the 2007 WHO classification scheme [5]. All cases from our institution were retrospectively reviewed by a single neuropathologist (B.P.).

For microarray experiments, approximately 15 μg total RNA extracted from frozen tumor tissues with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was converted to cDNA, purified, and used as a template for the in vitro transcription of biotin-labeled complementary RNA (cRNA). All reactions were performed following the manufacturer's instructions (Affymetrix UK Ltd., High Wycombe, UK).

For the LOH analysis, normal genomic DNA (from peripheral blood leukocytes) and tumor genomic DNA were isolated using the Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Qiagen Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. When fresh-frozen tissue was not available, tumor genomic DNA was extracted from Carnoy-fixed and paraffin-embedded blocks following a standard phenol/chloroform method.

Total RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

For the real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, 1 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed using a high-capacity cDNA synthesis kit after treatment with DNAseI. Amplification of a β2M cDNA–specific fragment was used as a control for this reaction (supplemental online data).

Microarray Hybridization

Microarray analysis was performed on 23 meningioma specimens, including nine transitional (WHO grade I), one meningothelial (WHO grade I), 10 atypical (WHO grade II), and three anaplastic (WHO grade III) samples. Prior to Affymetrix HG U133A (Affymetrix UK Ltd.) chip hybridization, cRNA quality and integrity were controlled with a Test3 array provided by the manufacturer. Fluorescence intensities were measured with a laser scanner (Affymetrix GeneChip® Scanner 3000). The resulting 16-bit data files were imported into the GeneChip® operating software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) for image analysis and CEL file generation.

CEL files were then loaded into GeneSpring®, version 7.0 (Agilent Technologies) and submitted to robust multichip average (RMA) manipulation for quantitative expression level estimation, background correction, and normalization.

Microarray Data Analysis

The initial dataset was subjected to filtering for the removal of all probe sets whose expression value did not emerge from the background noise or did not vary among the different samples. This was achieved by filtering first on the detection call and eliminating all transcripts that were “absent” in all samples. Of 22,283 probe sets represented on the chip, 15,159 were used for further analysis.

Hierarchical clustering was applied to obtain an unsupervised visualization of the data, in order to verify the possible presence of particular structures describing the dataset.

In order to identify genes with the most significant differential expression between WHO grade I and WHO grade II and III meningiomas, the Limma modified t-test was performed, selecting only those genes whose expression level varied between the two groups with a p-value <.05 [18]. Further examination involved more filtering on fold (>2) and difference (>100) change, on the basis of the average expression level of each probe set within the different groups considered.

The resulting gene lists were inspected by functional enrichment analysis, using Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer, which enables the discovery of significantly overrepresented gene ontology (GO) categories within each list.

LOH Studies

To investigate the presence of allelic losses associated with different grades of meningiomas, we assessed LOH on 40 tumor samples and on the corresponding normal lymphocytes. Of these, 24 were benign, 14 were atypical, and two were anaplastic meningiomas. The following microsatellite loci were amplified by PCR (primer sequences are available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov and are listed in supplemental online Table S1): D1S2743, D1S234, D1S457, D1S157, D9S171, D10S212, D10S562, D10S190, D14S43, D14S81, D14S288, D22S264, D22S304, and D22S929. PCR products were analyzed on an AbiPrism 3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and quantitative analysis of the signal intensity was carried out with Gene Mapper version 4.0 software (Applied Biosystems). A tumor was considered to have LOH at a certain microsatellite locus when the tumor sample showed a ≥50% allelic signal reduction or increase. The overall extent of LOH for each tumor was calculated as the fractional allelic loss (FAL) ratio, by dividing the number of markers showing LOH by the number of all informative markers for each tumor sample. Tumors were then categorized as low FAL (< 0.25), medium FAL (0.25–0.50), or high FAL (>0.50).

Real-Time PCR

To validate selected microarray data, real-time PCR analysis was initially conducted on a wider group of 32 samples for the relative expression quantification of baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis repeat-containing 5 (BIRC5; Hs00153353_m1), cyclin-dependent kinases regulatory subunit 2 (CKS2; Hs00854958_g1), LIM domain and actin binding 1 (LIMA1; Hs00212557_m1), leptin receptor (LEPR; Hs00174492_m1), and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 3 (TIMP3; Hs00165949_m1), with the use of a GeneAmp® 5700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems). Each gene was studied with TaqMan chemistry and the use of a specific Assay on Demand (Applied Biosystems). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Hs99999905_m1) and 18S (Hs99999901_s1) RNA were chosen as reference genes and commercial RNA from human normal leptomeninges (Ambion, Austin, TX) was used as a calibrator for the calculation of fold expression levels with the ΔΔCt method [19].

For the two most significant genes, the sample size was enlarged to a total of 23 WHO grade II of III meningiomas, 32 grade I meningiomas from patients who did not recur for ≥5 years, and nine grade I meningiomas from patients who recurred <5 years after gross total resection (men041, men044, men047, men049, men051, men053, men096, men097, and men098). In order to obtain the maximal discrimination between WHO grade I and WHO grade II or III meningiomas, we normalized gene expression data on housekeeping genes and then subtracted CKS2 ΔCt from LEPR ΔCT, obtaining ΔΔCt. 2−ΔΔCt was used for evaluation of the relative expression of the two target genes. The following example is provided to explain the procedure we followed and refers to tumor men001.

The mean Ct (cycle threshold) for 18S used as an internal control was 9.933 ± 0.021 (value A), the mean Ct for CKS2 was 32.715 ± 0.262 (value B), and the mean Ct for LEPR was 30.470 ± 0.171 (value C).

−ΔΔCt = (A − C) − (A − B) = A − C − A + B = B − C. In this example, B − C corresponds to 32.715 − 30.470 = 2.245. Thus 2−ΔΔCt corresponds to 22.245 and the C-L index is 4.740.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Surgical specimens were fixed in Carnoy, paraffin embedded, and sectioned at 4 μm for the histological analysis. The immunohistochemical study was performed on paraffin-embedded sections using the following antibodies: anti-human monoclonal antibody CKS2 (1:20; LifeSpan Bioscience, Seattle WA) and anti-human polyclonal LEPR (1:20; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Sections were deparaffinized in xylene and tissue endogenous peroxidase was blocked by 3% H2O2. Antigen retrieval was carried out in sodium citrate (0.01 mol/L; pH, 6.0) in a water bath at 98°C for 40 minutes. Sections were rinsed in Tris buffer, incubated with normal goat serum (1:20) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for CKS2 and in rabbit serum (1:20) for LEPR for 20 minutes, then incubated overnight in a humidified chamber with the primary antibodies diluted in Tris buffer.

After three washes in buffer, sections were incubated for 1 hour with envision peroxidase conjugate for CKS2 and secondary biotinylated anti-goat antibody and horseradish peroxidase streptavidin (1:300; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for LEPR. Finally, sections were rinsed and reacted with diaminobenzidine (Liquid DAB Substrate Chromogen System; DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA), counterstained, and mounted.

Tumors were categorized as positive when they exhibited moderate to strong plasma membrane and/or cytoplasmic staining or nuclear staining in the majority of tumor cells, which was easily visible with a low-power objective.

Paraffin-embedded sections were analyzed with the following antibodies: anti-human monoclonal antibody CKS2 (1:20; LifeSpan Bioscience) and anti-human polyclonal LEPR (1:20; R&D Systems). Tissue endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide and antigen retrieval was carried out in sodium citrate (0.01 mol/L; pH, 6.0) in a water bath at 98°C for 40 minutes. Paraffin-embedded sections were blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS for 60 minutes and incubated overnight with primary antibodies. Tissue sections were washed in PBS and incubated with secondary biotinylated antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour. Detection of antibody binding was done using a Vectastain-Elite Avidin–Biotin Complex-Peroxidase kit (Vector Laboratories) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Results

Microarray Analysis

Twenty-three meningiomas were analyzed by DNA microarray analysis using Affymetrix GeneChip® HGU133A, which enables the monitoring of >14,000 well-known genes and 7,000 expressed sequence tags. Clinical data are reported in supplemental online Table S2, pivot data are reported in supplemental online Table S3. Expression values for each hybridized chip were calculated and submitted to quintile normalization through the RMA algorithm. Of all probe sets represented on the chip, 15,159 passed the first filtering on detection call, thus eliminating all transcripts detected as absent.

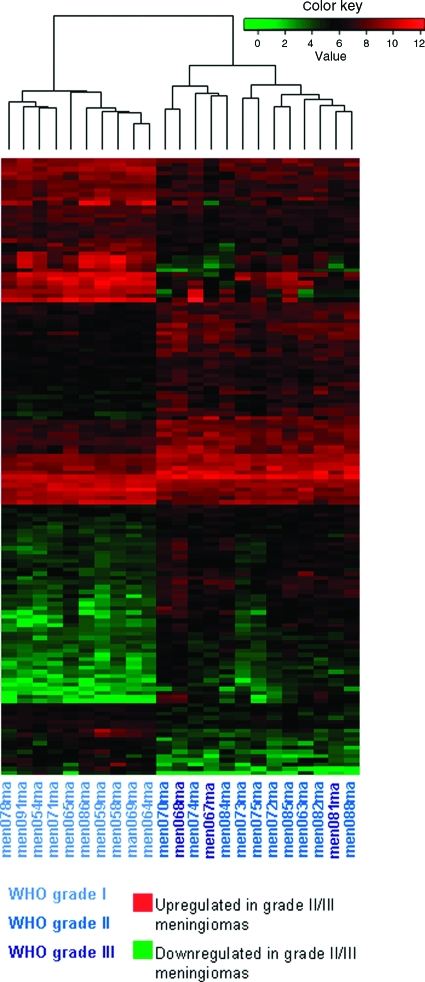

The resulting 15,159 probe sets were used for an exploratory analysis of the dataset. Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis applying a p-value < .01 as the cutoff revealed the tendency of WHO grade II and III tumors to cluster together and separate from WHO grade I tumors (Fig. 1). The clustering tree also shows that histological grade was the strongest parameter affecting the clustering results, separating tumor samples better than other parameters.

Figure 1.

Heatmap showing the expression patterns of the 146 transcripts that were most significantly up- or downregulated in high- versus low-grade meningiomas (p < .01).

Abbreviation: WHO, World Health Organization.

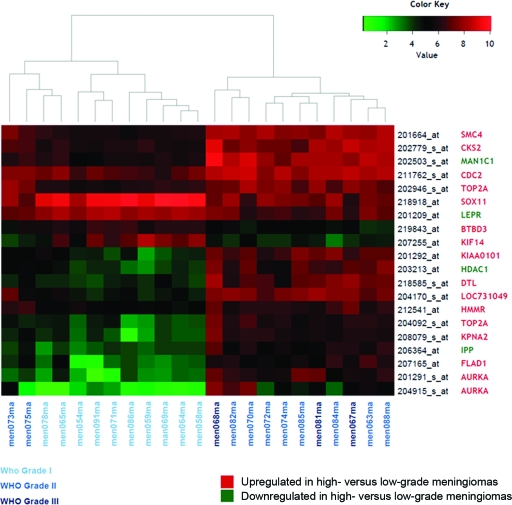

Figure 2 shows a heatmap representing the expression patterns of the 20 probe sets that were most significantly up- or downregulated in high-grade versus low-grade meningiomas.

Figure 2.

Heatmap showing the expression patterns of the 20 probe sets that were most significantly up- or downregulated in high- versus low-grade meningiomas. The leptin receptor gene (LEPR) corresponds to 207255_at and the cyclin-dependent kinases regulatory subunit 2 (CKS2) gene corresponds to 204170_s_at. Identification of the other genes shown in the figure is available in supplemental online Table S3.

Abbreviation: WHO, World Health Organization.

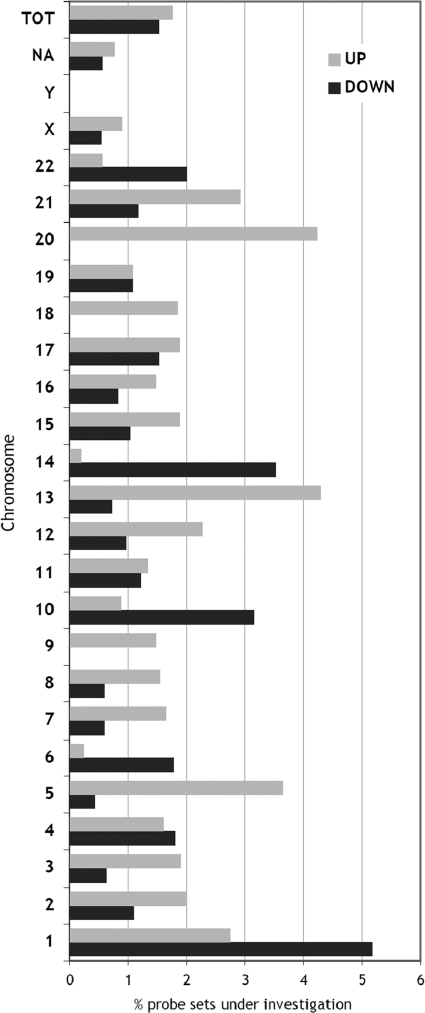

Because some chromosomes may be specifically involved in the tumorigenesis process, by housing a significant part of down- or upregulated genes, we analyzed the chromosomal distribution of the selected probe sets compared with the original distribution of all probe sets on each chromosome. As shown in Figure 3, chromosomes 1, 6, 10, 14, and 22 show a significant overrepresentation of genes downregulated in high-grade meningiomas, whereas chromosomes 1, 5, 9, 13, and 20 are enriched in upregulated genes.

Figure 3.

Chromosomal distribution of the up- and downregulated probe sets (268 and 233 probe sets; p < .05). For every chromosome, the proportion of differentially expressed probe sets is computed on the number of probe sets investigated for statistical analysis mapping on that chromosome.

The two lists of differentially down- and upregulated genes were submitted to GO analysis to look for specific biological categories that may underlie the functional meaning of the selections. No significant enrichment in GO terms was found in the list of downregulated genes; in contrast, the list of upregulated genes showed a strong and significant enrichment of GO subgroups associated with cell proliferation and division, including the mitotic cell cycle, nuclear division, cell cycle checkpoint, and DNA metabolism (supplemental online Fig. S1).

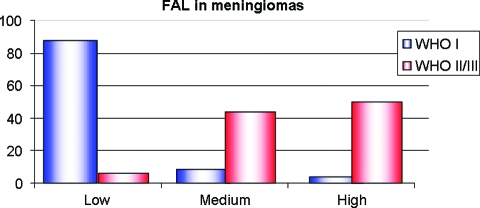

LOH

LOH analysis was performed for the 40 patients from whom blood samples were available: 24 WHO grade I, 14 WHO grade II, and two WHO grade III meningiomas. Five chromosomal regions (1p, 9p, 10q, 14q, and 22q) were examined, because previous data suggested that they may contain regions of frequent allelic imbalance. All five regions showed more frequent losses in high-grade than in low-grade meningiomas. When looking at the global LOH pattern of each sample using FAL analysis, 87.5% of WHO grade I but only 6.25% of WHO grade II or III meningiomas were low FAL. Most high-grade meningiomas were classified as medium (43.8%) or high (50.75%) FAL (Fig. 4 and supplemental online Table S4).

Figure 4.

FAL ratio in meningiomas: Most WHO grade I (blue bars) and <10% of WHO grade II or III meningiomas (red bars) displayed low FAL.

Abbreviations: FAL, fractional allelic loss; WHO, World Health Organization.

Real-Time PCR

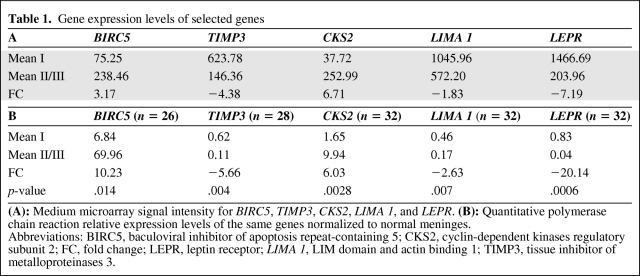

Five genes were selected for validation analysis by real-time PCR on a wider and partially independent group of samples. These included two genes that were upregulated in high-grade compared with low-grade meningiomas—BIRC5 (17q25.3) and CKS2 (9q22.2)—and three genes that were downregulated—LIMA1 (12q13.3), TIMP3 (22q12.3), and LEPR (1p313). They were chosen either because of their biological relevance or because of their strong deregulation associated with tumor grade. Real-time PCR performed on 32 meningiomas confirmed to have higher expression of BIRC5 (p = .014) and CKS2 (p = .0028) and lower expression of TIMP3 (p = .004), LIMA1 (p = .007), and LEPR (p = .0006), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Gene expression levels of selected genes

(A): Medium microarray signal intensity for BIRC5, TIMP3, CKS2, LIMA 1, and LEPR. (B): Quantitative polymerase chain reaction relative expression levels of the same genes normalized to normal meninges.

Abbreviations: BIRC5, baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis repeat-containing 5; CKS2, cyclin-dependent kinases regulatory subunit 2; FC, fold change; LEPR, leptin receptor; LIMA 1, LIM domain and actin binding 1; TIMP3, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 3.

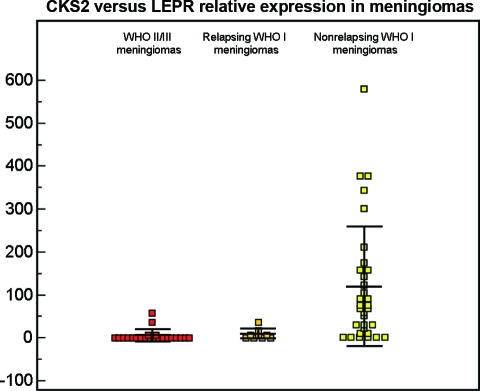

We further selected CKS2 and LEPR because they were the most significantly up- and downregulated genes, respectively, in grade II and grade III meningiomas. In order to evaluate the prognostic value of their expression, we considered 65 meningiomas from first surgeries: 24 WHO grade II or III meningiomas, 32 WHO grade I meningiomas from patients with a follow-up ≥5 years without recurrence, and nine WHO grade I meningiomas from patients who underwent complete surgical resection but recurred within 5 years. We performed quantitative PCR evaluating the relative expression level of LEPR versus CKS2 (C-L index) and found that the difference between WHO grade I and WHO grade II or III (119.48 ± 139.40 versus 5.72 ± 14.28) meningiomas was highly significant (p = .0004) (Fig. 5). Moreover, the C-L index of the nine meningiomas from patients who recurred was 10.07 ± 11.48 and was significantly different from the C-L index of WHO grade I meningiomas, despite the small sample size (p = .025) (Fig. 5). The difference between relapsing WHO grade I meningiomas and WHO grade II or III meningiomas was not significant (p = .42).

Figure 5.

Dots represent relative expression levels between the leptin receptor gene (LEPR) and the cyclin-dependent kinases regulatory subunit 2 gene (CKS2) from the quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of WHO grade II or III (red dots) and WHO grade I (yellow dots) meningiomas. The dot plot chart represents relative expression values. The striped dots represented WHO grade I meningiomas from patients who underwent gross total resection but recurred in <5 years. Differences between WHO grade I and WHO grade II or III were highly significant (p = .0004) as was the difference between recurrent and nonrecurrent grade I meningiomas (p = 0.025), whereas no statistical difference was seen between WHO grade II or III meningiomas and WHO grade I meningiomas from relapsing patients (p = .42).

Abbreviation: WHO, World Health Organization.

Immmunohistochemistry

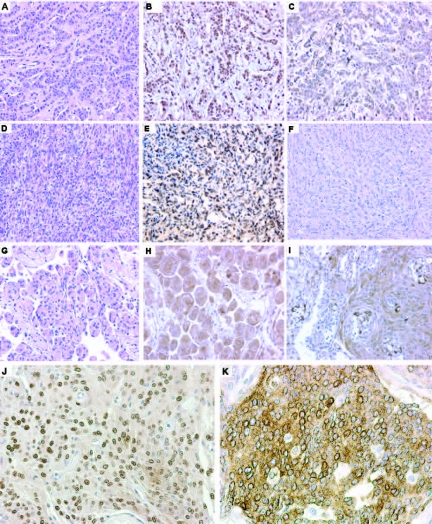

In order to obtain confirmation of the presence of CKS2/18S by immunohistochemistry (IHC), we studied the expression of CKS2 and LEPR by specific antibodies in 42 meningiomas, including nine from patients with recurrence. At first surgery, they were diagnosed as WHO grade I (n = 29) or WHO grade II (n = 10) meningiomas.

CKS2 was variably expressed in neoplastic cells; staining was localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6K) or in the nucleus (Fig. 6E, 6J), or in both, with variable intensity. Transitional meningiomas showed strong cytoplasmic staining in typical whorls (Fig. 6G, 6H) and nuclear staining in the stromal component. In secretory meningiomas, we observed strong cytoplasmic staining of CKS2 around secretory bodies (Fig. 6I), corresponding to epithelial differentiation. Atypical meningiomas showed variable positivity for CKS2 in the cytoplasm and nucleus.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemical panel. A specimen of breast carcinoma (A) showed a positive signal for CKS2 (B) and LEPR (C). Expression of anti-CKS2 (E, H, I) and anti-LEPR (F) antibodies in different meningiomas (D, G). (J, K): Details of the nuclear and cytoplasmic staining pattern of CKS2.

Abbreviations: CKS2, cyclin-dependent kinases regulatory subunit 2; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; LEPR, leptin receptor.

In three WHO grade I meningiomas from patients who relapsed, the same IHC pattern was observed—CKS2 was present in the cytoplasm of neoplastic cells but not in the nucleus. These results support the above-mentioned hypothesis that genetic alterations present in recurrent tumors were already present in the initial tumor.

In our IHC study, leptin receptor was negative in all cases investigated (Fig. 6F). Breast metastases were used for control.

Discussion

As a frequently benign tumor, meningioma, albeit not rare, does not pose a relevant clinical danger. Its malignant evolution, at present, is treated using only surgery and radiotherapy, because no effective chemotherapy is available. Thus, the capacity to predict recurrence may favor early and radical reintervention, increasing the chances for prolonged control of the disease. Histological analysis of grade I meningiomas, however, does not seem to provide robust prognostic tools: Only recently, osteopontin was proposed as a possible predictor of meningioma recurrence but data should be validated using a larger sample size [20]. On the other hand, the growing body of information on genetic abnormalities in meningiomas may provide prognostic tools of clinical interest.

LOH studies were the first to show an association with clinical grade, with 1p and 14q losses having a prominent role [21–24] in association with high-grade meningiomas. LOH on 22q, where NF2 is located, is also diffuse in grade I meningiomas and does not appear to be linked to greater malignancy [25–27]. Our observations corroborate these findings. As displayed in Figure 4 and in supplemental online Table S4, there was a good correlation between tumor grade and FAL, in agreement with previous data suggesting a link between a higher number of chromosomal aberrations and meningioma grade. Based on that, a model of genetic progression was proposed for meningiomas, similar to other malignancies [25]. Subsequent data, however, suggested that genetic alterations present in recurrent, grade II–III meningiomas were already present in the initial tumor, failing to confirm the “progression” model [28, 29]. Our observations support correlations between LOH data and histological analysis, are unable to support the “progression” model, and do not increase the prognostic power of LOH. To this goal, we have examined expression profiling in meningiomas of different grades. The results of these studies are in good agreement with other investigations. Using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis on a microarray study of 30 meningiomas, Wrobel et al. [30] found 27 genes that were significantly upregulated in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas. Genes involved in proliferation programs were highly represented and CKS2 had the highest ROC score in the list [30]. Using a combination of gene expression microarrays and array comparative genomic hybridization, Carvalho et al. [31] showed that 23 meningiomas of all three grades fell into two main molecular groups designated “low-proliferative” and “high-proliferative” meningiomas; CKS2 was highly expressed in grade III versus grade I meningiomas. Genes involved in proliferation pathways, including CKS2, were again found to be upregulated in a microarray study on 17 meningiomas [32]. Overall, these studies and our work point to CKS2 as a robust marker associated with meningioma recurrence and malignant transformation. Cks2 is required for the first metaphase/anaphase transition of mammalian meiosis, and was also found to be upregulated in colon cancer metastases [33, 34], prostate and gastric cancer [35, 36], and hepatocellular carcinomas [37]. Recent data showed that gene expression of cyclin-dependent kinase subunit Cks2 is repressed by the tumor suppressor p53 [38]. Although p53 mutations are rare in meningiomas [39], several reports showed higher expression in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas [40, 41] and in one set of data based on an analysis of 80 meningiomas, specifically in grade I relapsing meningiomas [42]. These observations support future investigations on the relationship between higher p53 and CKS2 expression levels in meningiomas that switch to aggressive patterns of growth.

Our work also points to the gene encoding the leptin receptor, LEPR, as a novel marker of interest in meningiomas. Strong downregulation of LEPR expression, which we found in grade II–III meningiomas, may disrupt the leptin–LEPR feedback loop and cause higher levels of leptin in the central nervous system, as observed in obese (fa/fa) Zucker rats carrying a recessive, loss of function mutation in LEPR [43]. Interestingly, higher leptin levels resulting from leptin resistance may be associated with obesity [44], a condition that some studies found to be present significantly more often in meningioma patients [45–47]. Molecular mechanisms underlying LEPR downregulation, as well as consequences in terms of intracellular signaling in meningiomas, however, are unclear at this time. Nevertheless, we find that the combined investigation of CKS2 and LEPR and the meningioma progression index that it may express provides a potentially powerful indicator of meningioma progression even in tumors that are histologically graded as benign. This observation needs to be validated in a large, prospective study before being proposed for everyday clinical use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sergio Giombini and other colleagues of the Department of Neurosurgery of Istituto Besta for making available meningioma specimens, Dr. Lorena Bissola for initial collaboration on the LOH studies, Dr. Maria Grazia Bruzzone for help in MRI analysis of relapsing patients, and Dimos Kapetis (Genopolis) for useful discussion on microarray data.

Francesca Menghi and Francesca N. Orzan contributed equally to this manuscript.

This work was supported by funds of the Italian Minister of Health to G.F.

Francesca Menghi's present address is: Molecular Haematology and Cancer Biology Unit, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust, London, WC1N 3JH, UK.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Gaetano Finocchiaro, Francesca Menghi

Provision of study material or patients: Sandro Lodrini, Giuseppe Galli, Emanuela Maderna, Federica Pisati

Collection and/or assembly of data: Francesca Orzan, Lorella Valletta, Bianca Pollo, Francesca Menghi, Marica Eoli, Mariangela Farinotti, Donatella Bianchessi, Emanuela Maderna, Federica Pisati, Elena Anghileri, Serena Pellegatta

Data analysis and interpretation: Gaetano Finocchiaro, Bianca Pollo, Francesca Menghi, Francesca Orzan, Marica Eoli

Manuscript writing: Gaetano Finocchiaro

Final approval of manuscript: Gaetano Finocchiaro

References

- 1.Kalamarides M, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Niwa-Kawakita M, et al. Identification of a progenitor cell of origin capable of generating diverse meningioma histological subtypes. Oncogene. 2011;30:2333–2344. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamszus K. Meningioma pathology, genetics, and biology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:275–286. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.4.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, et al. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1821–1828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blitshteyn S, Crook JE, Jaeckle KA. Is there an association between meningioma and hormone replacement therapy? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:279–282. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber DC, Lovblad KO, Rogers L. New pathology classification, imagery techniques and prospective trials for meningiomas: The future looks bright. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:563–570. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328340441e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry A, Scheithauer BW, Stafford SL, et al. “Malignancy” in meningiomas: A clinicopathologic study of 116 patients, with grading implications. Cancer. 1999;85:2046–2056. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990501)85:9<2046::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sioka C, Kyritsis AP. Chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and immunotherapy for recurrent meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2009;92:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9734-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen PY, Yung WK, Lamborn KR, et al. Phase II study of imatinib mesylate for recurrent meningiomas (North American Brain Tumor Consortium study 01–08) Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:853–860. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2009-010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norden AD, Drappatz J, Wen PY. Advances in meningioma therapy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009;9:231–240. doi: 10.1007/s11910-009-0034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruttledge MH, Sarrazin J, Rangaratnam S, et al. Evidence for the complete inactivation of the NF2 gene in the majority of sporadic meningiomas. Nat Genet. 1994;6:180–184. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lekanne Deprez RH, Bianchi AB, Groen NA, et al. Frequent NF2 gene transcript mutations in sporadic meningiomas and vestibular schwannomas. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54:1022–1029. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JH, Kim IS, Kwon SY, et al. Mutational analysis of the NF2 gene in sporadic meningiomas by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Int J Mol Med. 2006;18:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curto M, McClatchey AI. Nf2/Merlin: A coordinator of receptor signalling and intercellular contact. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:256–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riemenschneider MJ, Perry A, Reifenberger G. Histological classification and molecular genetics of meningiomas. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:1045–1054. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mawrin C, Perry A. Pathological classification and molecular genetics of meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2010;99:379–391. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boström J, Meyer-Puttlitz B, Wolter M, et al. Alterations of the tumor suppressor genes CDKN2A (p16(INK4a)), p14(ARF), CDKN2B (p15(INK4b)), and CDKN2C (p18(INK4c)) in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:661–669. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61737-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng KY, Chung MH, Sytwu HK, et al. Osteopontin expression is a valuable marker for prediction of short-term recurrence in WHO grade I benign meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2010;100:217–223. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai DX, Banerjee R, Scheithauer BW, et al. Chromosome 1p and 14q FISH analysis in clinicopathologic subsets of meningioma: Diagnostic and prognostic implications. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:628–636. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.6.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Gines C, Cerda-Nicolas M, Gil-Benso R, et al. Association of loss of 1p and alterations of chromosome 14 in meningioma progression. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;148:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(03)00279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leuraud P, Dezamis E, Aguirre-Cruz L, et al. Prognostic value of allelic losses and telomerase activity in meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:303–309. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.2.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Glez V, Alvarez L, Franco-Hernàndez C, et al. Genomic deletions at 1p and 14q are associated with an abnormal cDNA microarray gene expression pattern in meningiomas but not in schwannomas. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;196:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber RG, Boström J, Wolter M, et al. Analysis of genomic alterations in benign, atypical, and anaplastic meningiomas: Toward a genetic model of meningioma progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14719–14724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leone PE, Bello MJ, de Campos JM, et al. NF2 gene mutations and allelic status of 1p, 14q and 22q in sporadic meningiomas. Oncogene. 1999;18:2231–2239. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buccoliero AM, Castiglione F, Degl'Innocenti DR, et al. NF2 gene expression in sporadic meningiomas: Relation to grades or histotypes real time-PCR study. Neuropathology. 2007;27:36–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2006.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiffer D, Ghimenti C, Fiano V. Absence of histological signs of tumor progression in recurrences of completely resected meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2005;73:125–130. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-4207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Mefty O, Kadri PA, Pravdenkova S, et al. Malignant progression in meningioma: Documentation of a series and analysis of cytogenetic findings. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:210–218. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.2.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wrobel G, Roerig P, Kokocinski F, et al. Microarray-based gene expression profiling of benign, atypical and anaplastic meningiomas identifies novel genes associated with meningioma progression. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:249–256. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carvalho LH, Smirnov I, Baia GS, et al. Molecular signatures define two main classes of meningiomas. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:64. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fèvre-Montange M, Champier J, Durand A, et al. Microarray gene expression profiling in meningiomas: Differential expression according to grade or histopathological subtype. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:1395–1407. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li M, Lin YM, Hasegawa S, et al. Genes associated with liver metastasis of colon cancer, identified by genome-wide cDNA microarray. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiese AH, Auer J, Lassmann S, et al. Identification of gene signatures for invasive colorectal tumor cells. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31:282–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lan Y, Zhang Y, Wang J, et al. Aberrant expression of Cks1 and Cks2 contributes to prostate tumorigenesis by promoting proliferation and inhibiting programmed cell death. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:543–551. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang MA, Kim JT, Kim JH, et al. Upregulation of the cycline kinase subunit CKS2 increases cell proliferation rate in gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:761–769. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0510-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen DY, Fang ZX, You P, et al. Clinical significance and expression of cyclin kinase subunits 1 and 2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2010;30:119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rother K, Dengl M, Lorenz J, et al. Gene expression of cyclin-dependent kinase subunit Cks2 is repressed by the tumor suppressor p53 but not by the related proteins p63 or p73. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1166–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verheijen FM, Sprong M, Kloosterman JM, et al. TP53 mutations in human meningiomas. Int J Biol Markers. 2002;17:42–48. doi: 10.5301/jbm.2008.3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguiar PH, Agner C, Simm R, et al. p53 protein expression in meningiomas—a clinicopathologic study of 55 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2002;25:252–257. doi: 10.1007/s10143-002-0204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang SY, Park CK, Park SH, et al. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: Prognostic implications of clinicopathological features. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:574–580. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.121582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamei Y, Watanabe M, Nakayama T, et al. Prognostic significance of p53 and p21WAF1/CIP1 immunoreactivity and tumor micronecrosis for recurrence of meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2000;46:205–213. doi: 10.1023/a:1006440430585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Picó C, Sànchez J, Oliver P, et al. Leptin production by the stomach is up-regulated in obese (fa/fa) Zucker rats. Obes Res. 2002;10:932–938. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Correia ML, Haynes WG. Leptin, obesity and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004;13:215–223. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200403000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobs DH, McFarlane MJ, Holmes FF. Meningiomas and obesity reconsidered. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:376. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider B, Pülhorn H, Röhrig B, et al. Predisposing conditions and risk factors for development of symptomatic meningioma in adults. Cancer Detect Prev. 2005;29:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aghi MK, Eskandar EN, Carter BS, et al. Increased prevalence of obesity and obesity-related postoperative complications in male patients with meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:754–760. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000298903.63635.E3. discussion 760–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.