The rationale for the use of epothilones in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer is highlighted and the clinical data concerning epothilones in this setting are summarized.

Keywords: Epothilones, Castration-resistant prostate cancer, Chemotherapy, Taxanes

Abstract

The management of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) presents a clinical challenge because of limitations in efficacy and durability with currently available therapeutics. The epothilones represent a novel class of anticancer therapy that stabilizes microtubules, causing cell death and tumor regression in preclinical models. The structure of the tubulin-binding site for epothilones is distinct from that of the taxanes. Moreover, preclinical studies suggest nonoverlapping mechanisms of resistance between epothilones and taxanes. In early-phase studies in patients with CRPC, treatment with ixabepilone, a semisynthetic analog of epothilone B, induced objective responses and prostate-specific antigen declines in men previously progressing on docetaxel-based regimens. Clinical activity has been observed in nonrandomized trials for patients with CRPC using ixabepilone in the first- and second-line settings as a single agent and in combination with estramustine. Patupilone and sagopilone were also shown to have promising efficacy in phase II clinical trials of patients with CRPC. All three epothilones appear to be well tolerated, with modest rates of neutropenia and peripheral neuropathy. The lack of crossresistance between epothilones and taxanes may allow sequencing of these agents. Evaluating epothilones in phase III comparative trials would provide much-needed insight into their potential place in the management of patients with CRPC.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is a heterogeneous disease. Many patients are diagnosed with a clinically indolent form of prostate cancer that does not adversely affect overall survival whereas others experience an aggressive form of the disease that can ultimately prove to be fatal. Castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) encompasses an often lethal form of prostate cancer that has progressed despite androgen-deprivation therapy. In treating CRPC patients, clinicians choose among the many therapeutic options available, including salvage hormonal agents and cytotoxic chemotherapy. Previously, salvage hormonal manipulations used in CRPC patients included antiandrogens (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) and androgen synthesis inhibitors (such as ketoconazole). Similarly, a variety of cytotoxic agents are active in CRPC patients, including taxanes, anthracyclines, platinum compounds, etc. Recently, a new androgen synthesis inhibitor, abiraterone, and a new taxane, cabazitaxel, were approved for docetaxel-treated CRPC patients. Late-phase trials are testing other salvage hormonal agents for CRPC, including an antiandrogen (MDV3100) and an androgen synthesis inhibitor (TAK-700). This review focuses on the rationale for the use of epothilones in patients with CRPC and summarizes the clinical data concerning epothilones in this setting.

Chemotherapy for CRPC

Docetaxel for Chemotherapy-Naïve CRPC Patients

The results from two large, randomized phase III clinical trials published in 2004 (Southwest Oncology Group [SWOG] 9916 and TAX 327) showed that docetaxel-based chemotherapy extends overall survival (OS) by approximately 2–3 months in patients with CRPC [1, 2]. These data supported the approval of docetaxel for CRPC by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and national prostate cancer treatment guidelines now recommend 3-weekly docetaxel and prednisone as the preferred first-line chemotherapy option for patients with CRPC [3]. However, it is also clear that there is a great need to improve upon the results of docetaxel-based treatment as first-line therapy for CRPC patients; the median progression-free survival (PFS) interval is ∼6 months and the median OS duration is 19.2 months [1, 2]. Changes in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels have been used as a measure of efficacy for cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens for CRPC patients. In chemotherapy-naïve patients, a PSA response (≥50% decline from baseline) is achieved in ∼50% of patients [1, 2]. Similarly, the palliation of bone pain is of critical importance in the management of patients with CRPC. Pain palliation, defined as a two-point reduction in the McGill-Malzack pain score without an increase in narcotic medication use, was achieved in 21% of patients in the SWOG 9916 trial treated with docetaxel [4]. Achievement of this important goal in a minority of patients further highlights the need for more effective therapies for CRPC.

Docetaxel-Resistant CRPC

Treatment for docetaxel-resistant CRPC is becoming a major unmet need for patients with advanced prostate cancer because no standard treatment exists for this clinical situation [5]. Mitoxantrone with prednisone is the only other cytotoxic regimen indicated for CRPC based on a palliative benefit (improvement in the McGill-Melzack bone pain score) rather than a prolongation of OS [6, 7]. PSA response, as defined above, occurs in approximately 20%–30% of patients treated with mitoxantrone in the first-line setting [1, 2, 6, 7] and in 15% of patients treated in the second-line setting following docetaxel [8, 9]. Taken together, these data suggest only modest activity for mitoxantrone as a first- or second-line agent for CRPC treatment. In clinical practice, mitoxantrone is often reserved as a salvage agent for patients with widespread metastatic CRPC and significant bone pain. Other treatment strategies for docetaxel-refractory CRPC include changing the dose or schedule of docetaxel and adding other agents (such as estramustine, bortezomib, carboplatin, or samarium); however, these manipulations result in modest response rates and the impact on survival and quality of life are unknown [5, 10–13]. Platinum-based regimens (including satraplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin) are active in the post-docetaxel setting [14, 15]. However, satraplatin did not confer a significant survival advantage over prednisone when tested in the second-line chemotherapy setting for CRPC [15]. Other salvage cytotoxic agents that are used for docetaxel-resistant CRPC include capecitabine, gemcitabine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vinorelbine, and vincristine [16–22]. Most recently, treatment with a novel taxane—cabazitaxel—and prednisone led to longer survival than with mitoxantrone and prednisone in patients with docetaxel-treated CRPC [23]. Improving treatments and outcomes for patients with docetaxel-treated CRPC is becoming an important area for prostate oncology.

Understanding Epothilones

The epothilones represent a novel class of cytotoxic agents that stabilizes microtubules, leading to cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle and triggering death, especially in rapidly growing cells (i.e., malignant cells). Ixabepilone, a semisynthetic analog of epothilone B, is the most clinically advanced of the epothilones, with efficacy and tolerability shown in phase II and phase III trials of patients with recurrent advanced or metastatic breast cancer [24–26]. Ixabepilone was approved by the FDA in 2007 for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer in combination with capecitabine after failure of an anthracycline and a taxane, and as monotherapy after failure of an anthracycline, a taxane, and capecitabine. The efficacy of ixabepilone in this setting has stimulated interest in the evaluation of epothilones for other tumor types that are susceptible to chemotherapy resistance, including CRPC.

Of particular interest are data suggesting that epothilones are active in the setting of innate or acquired resistance to taxanes. Mechanistically, the main putative mechanism of action for epothilones is microtubule stabilization in a manner similar to that observed with taxanes [27]. Detailed structural studies have identified a taxane-binding site on the β-tubulin surface localized on the luminal (inner) surface of microtubules [28]. However, as macrolide antibiotics, the epothilones are structurally unrelated to taxanes and interact with a distinct surface on tubulin [29]. Sensitivity to epothilones is maintained in preclinical cellular models representing specific known mechanisms of intrinsic or acquired resistance to taxanes, including tubulin-isotype switching (overexpression of class III β-tubulin) and tubulin mutations [30]. Epothilones also circumvent some of the other mechanisms that tumor cells have evolved to promote survival, particularly, the overexpression of the multidrug resistance genes or proteins such as MDR-1 and MRP-1, part of the ATP-binding cassette superfamily [27, 29–31]. Unlike several other anticancer agents, such as docetaxel, paclitaxel, doxorubicin, etoposide, vincristine, and vinblastine, the epothilones are poor substrates for these transporters [29, 32, 33]. The antitumor potency, structural distinction from taxanes, and absence of susceptibility to two forms of taxane resistance have made the epothilones a candidate of interest for clinical testing in CRPC.

Ixabepilone, sagopilone (ZK-EPO, a synthetic formulation of epothilone B), and patupilone (natural epothilone B) were shown to have extensive antitumor activity against in vivo and in vitro tumor models, including prostate cancer [29, 34, 35]. These agents have also been shown to inhibit tumor growth in taxane-resistant cell lines, suggesting a lack of crossresistance between the two drug classes [27, 30, 36, 37].

Clinical Experience with Epothilones in CRPC

Ixabepilone

Ixabepilone is the only epothilone currently approved for use outside clinical trials. Phase I studies identified the activity of ixabepilone in a variety of tumor types, including prostate cancer, and defined the maximum-tolerated doses as 20 mg/m2 when administered weekly over 1 hour on a 28-day cycle and 25 mg/m2 when administered over 30 minutes on a continuous weekly basis [38]. The maximum-tolerated dose is 50 mg/m2 i.v. when administered on a 3-weekly dosing schedule, although 40 mg/m2 was chosen as the dose for most phase II and phase III studies [38–42]. The dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was fatigue with the weekly schedule, whereas neutropenia and mucositis were dose limiting with the 3-weekly dosing schedule; peripheral neuropathy was also a significant toxicity.

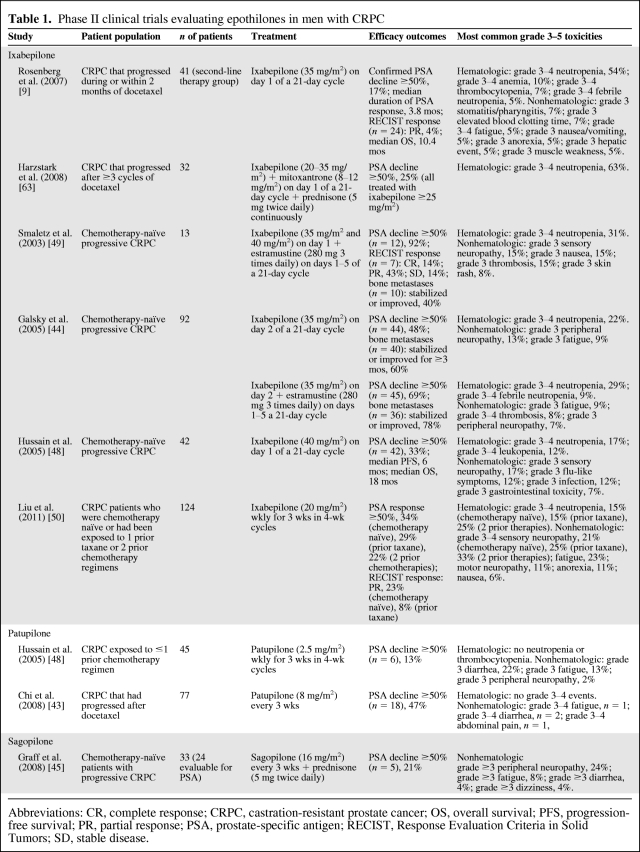

Ixabepilone was evaluated in a series of early-phase studies in patients with CRPC (summarized in Table 1) [9, 43–50], with promising antitumor activity as monotherapy and in combination with mitoxantrone and prednisone in men who have progressed on docetaxel. Furthermore, antitumor activity with ixabepilone has been observed in the first-line and docetaxel-resistant settings.

Table 1.

Phase II clinical trials evaluating epothilones in men with CRPC

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; SD, stable disease.

Chemotherapy-Naïve CRPC Patients

Ixabepilone was evaluated as a single agent in 42 patients with chemotherapy-naïve metastatic CRPC [48]. Patients received ixabepilone at a dose of 40 mg/m2 administered as a 3-hour i.v. infusion on day 1 of a 21-day cycle. Fourteen patients (33%) exhibited a PSA decline >50% that was confirmed on two successive occasions at least 4 weeks apart, which was the primary endpoint. The estimated median PFS interval was 6 months and the median OS time was 18 months. In patients with measurable disease, the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) were used to evaluate radiographic responses [51]. Of patients who had measurable disease at baseline (n = 20), one had an unconfirmed complete response (CR) (defined as the disappearance of all signs of cancer) and two had an unconfirmed partial response (PR). The most frequent grade 3 or 4 toxicities included sensory neuropathy, neutropenia, flu-like symptoms, and infection. Sensory neuropathy was generally mild (grade 1 or 2 in 17 patients, grade 3 in eight patients), associated with higher cumulative doses of ixabepilone, and improved following treatment termination.

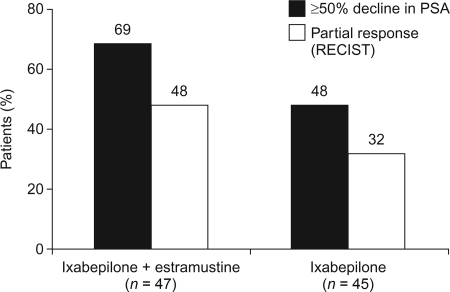

Estramustine was previously shown to enhance the anticancer activity of microtubule-targeting agents, both in vitro [52, 53] and in clinical studies [54, 55]. For this reason, a dose-finding study evaluating the safety of administering ixabepilone in combination with estramustine was performed in chemotherapy-naïve patients with prostate cancer who had progressed despite castration [49]. That study was subsequently expanded into a phase II randomized clinical trial comparing i.v. ixabepilone at a dose of 35 mg/m2 on day 2 of a 21-day cycle alone (n = 45) with ixabepilone at the same dose in combination with oral estramustine at a dose of 280 mg three times daily on days 1–5 (n = 47) [44]. Patients also received warfarin (2 mg/day) to prevent thromboembolism. In the phase II part of the study, a ≥50% PSA decline was achieved by 48% and 69% of patients treated with ixabepilone alone and ixabepilone plus estramustine, respectively (Fig. 1) [44]. The respective times to PSA progression were 4.4 months and 5.2 months. Tumor PRs (according to the RECIST) were reported in eight of 25 patients (32%) and in 11 of 23 patients (48%) with measurable disease at baseline, respectively. Furthermore, of the patients with bone metastases at baseline, 24 of 40 (60%) in the single-agent ixabepilone arm and 28 of 36 (78%) in the combination arm had stable or improved disease on bone scan for ≥3 months. In a retrospective analysis of patients who went on to receive second-line taxane therapy, 51% achieved a ≥50% PSA decline [9]. Responses were reported both in patients who had achieved a first-line response with ixabepilone (61%) and in those who had not (33%), indicating that there is incomplete crossresistance between these two classes of drug.

Figure 1.

Efficacy of ixabepilone alone or in combination with estramustine in patients with CRPC [44].

Abbreviations: CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

The most common hematologic toxicity in the phase II study [44] was neutropenia, which was grade ≥3 in 10 of 45 (22%) patients treated with ixabepilone alone and in 13 of 47 (29%) patients treated with ixabepilone plus estramustine. However, neutropenic fever was rare in both groups, occurring in two of 47 (4%) patients treated with ixabepilone alone and in four of 45 (9%) patients treated with ixabepilone plus estramustine. Peripheral sensory neuropathy was reported in 67% and 73% of patients treated with ixabepilone alone and ixabepilone plus estramustine, respectively. Most events were mild or moderate. In general, the neuropathy was characterized by paresthesias (tingling, pricking sensations), dysesthesias (burning, pricking, or itching), or numbness and improved or resolved with treatment cessation.

Weekly Dosing for Patients with Chemotherapy-Naïve or Resistant CRPC

In an attempt to reduce the rates of neutropenia, Liu and colleagues compared the activity and toxicity of ixabepilone (20 mg/m2 administered i.v. using a weekly schedule for 3 weeks of a 4-week cycle) in men with CRPC across a range of prior treatment exposures [50]. That phase II trial included patients who were chemotherapy naïve (n = 35), those who had received one prior taxane line (n = 42), and those who had received two prior lines of chemotherapy (n = 32). A ≥50% PSA decline was observed in 34%, 29%, and 22% of patients in the three treatment arms, respectively. Five of the chemotherapy-naïve patients with measurable disease at baseline achieved a PR using the RECIST (23%), as did two of the patients with prior taxane exposure (8%). Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia was observed in six (15%), seven (15%), and nine (25%) patients who were chemotherapy naïve, received a prior taxane, and received two prior chemotherapies, respectively. Grade 3 of 4 sensory neuropathy was observed in eight (21%), 12 (25%), and 12 (33%) patients in these arms, respectively. One patient in the two-prior-chemotherapies arm had grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia. The study investigators concluded that a weekly schedule of ixabepilone at 20 mg/m2 has acceptable toxicity, with less myelosuppression than previously observed with ixabepilone at 40 mg/m2 every 3 weeks, and that its single-agent activity met the prespecified efficacy criteria for patients previously treated with one or more lines of chemotherapy.

Docetaxel-Resistant CRPC

Given preclinical evidence for a lack of crossresistance between taxanes and ixabepilone [27, 29–31], there is a rationale for evaluating ixabepilone in patients with CRPC who have progressed on docetaxel.

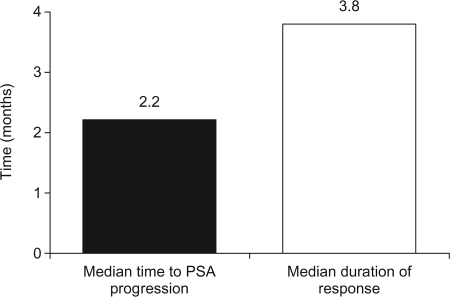

In order to test the efficacy of ixabepilone in this setting, second-line ixabepilone compared with mitoxantrone plus prednisone was evaluated in a phase II study in 82 patients with CRPC who had progressed during or within 2 months of completing first-line docetaxel [9]. Patients were randomized to treatment with either ixabepilone (35 mg/m2 by 3-hour i.v. infusion on day 1 of a 21-day cycle) or mitoxantrone (14 mg/m2 i.v. on day 1 of a 21-day cycle) plus continuous oral prednisone (5 mg twice daily). Patients who progressed on their allocated treatment were allowed to cross over to the alternative treatment arm. It should be noted, however, that the study was not powered to directly compare ixabepilone with mitoxantrone plus prednisone; therefore, no formal statistical analysis was performed between treatment groups. Seven patients treated with second-line ixabepilone had a confirmed decline in PSA ≥50% (17%), with another patient having an unconfirmed decline. The median time to PSA progression was 2.2 months and the median duration of response was 3.8 months (Fig. 2) [9]. Similar responses were reported with mitoxantrone plus prednisone. One of the 24 patients with measurable disease treated with ixabepilone (4%) had a PR using the RECIST, as did two of the 21 patients with measurable disease treated with mitoxantrone plus prednisone (10%). In an exploratory analysis, it was noted that patients who had previously responded to taxane therapy had a significantly greater response to second-line therapy with either ixabepilone or mitoxantrone (p = .0004). Of the patients who crossed over to third-line ixabepilone from mitoxantrone plus prednisone, 11% achieved a confirmed PSA response. None of those patients had responded to second-line mitoxantrone plus prednisone. The most common grade 3 or 4 toxicity in both treatment groups in the second-line setting was neutropenia (54% with ixabepilone and 63% with mitoxantrone plus prednisone). Although some nonhematologic toxicity occurred, none was observed with a high frequency. Grade 3 sensory neuropathy was noted in only one of 30 patients treated with ixabepilone in the third-line setting [9]. When ixabepilone is infused over 3 hours and used in docetaxel-pretreated CRPC patients with neuropathy grade ≤1, the observed incidence of progressive neuropathy (defined as grade ≥2) is generally <10%.

Figure 2.

Efficacy of second-line ixabepilone in patients with CRPC who had progressed on docetaxel [9].

Abbreviations: CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

The study described above indicated that single-agent ixabepilone has modest activity, similar to that of mitoxantrone plus prednisone, in men with CRPC who have progressed on docetaxel. Because of the different mechanisms of action and the lack of crossresistance between these regimens, Harzstark and colleagues investigated the regimens' additive or synergistic activity when administered together in men with metastatic CRPC who had progressed after three or more cycles of docetaxel [56, 57]. In a phase I trial, patients received escalating doses of i.v. ixabepilone (20–35 mg/m2) plus mitoxantrone (8–12 mg/m2) on day 1 of a 21-day cycle plus continuous prednisone (5 mg twice daily) to define a maximum-tolerated dose for the combination [57]. Of the six patients treated with ixabepilone at a dose of 30 mg/m2 plus mitoxantrone at a dose of 12 mg/m2, two experienced DLTs (grade 3 diarrhea and grade 4 neutropenia), and of the five patients treated with ixabepilone at a dose of 35 mg/m2 plus mitoxantrone at a dose of 12 mg/m2, another two experienced DLTs (both grade 4 neutropenia). These cohorts were then expanded with growth factor support, pegfilgrastim, on day 2 of each cycle. One grade 5 infection was reported in this expanded cohort. However, promising anticancer activity was noted, with eight patients (25%) experiencing a PSA response, all of whom were treated with an ixabepilone dose ≥25 mg/m2. The investigators concluded that the recommended phase II doses for the combination regimen were 35 mg/m2 for ixabepilone and 12 mg/m2 for mitoxantrone with pegfilgrastim. The results of a phase II study of this regimen recently demonstrated a 50% PSA decline in 25 of 56 evaluable patients (45%) and a reduction in measurable disease in eight of 36 patients (22%) [56]. Notable toxicities included grade 3 of 4 neutropenia in 32% of patients and grade 2 or 3 neuropathy in 24% of patients (patients with neuropathy grade >1 at baseline were excluded from that study).

Patupilone

Patupilone has been shown to have clinical activity in patients with advanced solid tumors [58] and is being evaluated in CRPC patients. In a phase II study, 45 patients who were chemotherapy naïve or had received one prior chemotherapy regimen for metastatic CRPC were treated with patupilone, 2.5 mg/m2 administered as a 5-minute i.v. infusion on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle (Table 1) [47]. Patients had measurable disease or PSA levels >20 ng/mL. Sixty-four percent of patients had previous chemotherapy (55% had previous taxane therapy) and patients received a median of three patupilone cycles. Patupilone was generally well tolerated; 10 patients (22%) had grade 3 diarrhea, six patients (13%) had grade 3 fatigue, and one patient (2%) had grade 3 peripheral neuropathy. There were no cases of neutropenia or thrombocytopenia. Six patients (13%) had a ≥50% decline in PSA (three of them had previous taxane therapy). No patient with measurable disease had a response, and the median OS duration was 13.4 months. The investigators concluded that the safety profile of weekly patupilone in CRPC patients compares favorably with that of other microtubule inhibitors, but there was minimal antitumor activity at the dose and schedule tested. Patupilone was tolerated at the full dose in a phase I trial of taxane-refractory breast or prostate cancer when combined with estramustine (280 mg twice daily on days 1–3) and showed more activity, with one RECIST PR in 14 patients [59].

Patupilone was also evaluated as a single agent in a phase II trial in 77 men with CRPC who had progressed during or within 6 months of receiving docetaxel [43]. In the first stage of that two-stage trial, patients were treated with patupilone at a dose of 10 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks. This dose was lowered to 8 mg/m2 after the first six patients were enrolled, because of a high incidence of severe diarrhea and vomiting. At the 8-mg/m2 dose, the grade 3 or 4 adverse events were fatigue (n = 1), diarrhea (n = 2), and abdominal pain (n = 1). Interim efficacy results found that PSA declines ≥30% and ≥50% occurred in 53% and 47% of patients, respectively, with a confirmed PSA response ≥50% occurring in 39% of patients. Of patients with measurable disease at baseline, 79% (15 of 19) had disease stabilization. Accrual to the second stage of that study is continuing.

Patupilone is also being compared with docetaxel, both in combination with prednisone, in chemotherapy-naïve CRPC patients (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00411528). The targeted accrual for that open-label study is 150 patients and the primary outcome measure is PSA response. In addition, patupilone is being evaluated as second-line therapy for CRPC patients after docetaxel in a phase II trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00407251).

Sagopilone

Sagopilone is currently under investigation for a number of tumor types, including CRPC. In a phase II study, chemotherapy-naïve patients were treated with a 3-hour i.v. infusion of sagopilone (16 mg/m2) every 21 days in combination with prednisone (5 mg twice daily) (Table 1) [45]. Twenty-nine patients were included in an interim analysis. Of the 24 patients evaluable for response, 21% had a confirmed reduction in PSA ≥50% and 58% had a reduction in PSA of 30%. Of the 12 patients with measurable disease at baseline, one had a confirmed CR and five had PRs (one of which was confirmed). Adverse events of grade ≥3 severity included peripheral neuropathy (24%), fatigue (8%), diarrhea (4%), and dizziness (4%).

Sagopilone is currently under investigation in a phase II trial as first-line therapy in combination with prednisone for patients with metastatic CRPC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00350051).

Discussion

Agents currently approved for patients with CRPC based on demonstration of a survival advantage over other therapies in phase III randomized trials include docetaxel, cabazitaxel, and abiraterone [1, 2, 23, 60]. Although docetaxel every 3 weeks is the standard of care for patients with the most aggressive forms of CRPC, 11% of patients withdrew from treatment as a result of an adverse event and progressive disease on treatment was observed in 38% of patients [2]. Similarly, although cabazitaxel is active in docetaxel-treated CRPC patients, reasons for treatment discontinuation include an adverse event or progressive disease in 18% and 48% of patients, respectively [23]. Preliminary data on abiraterone in docetaxel-treated CRPC patients show that, although abiraterone was well-tolerated (compared with placebo), PSA responses were observed in only 38% of patients [60]. Therefore, there is a need to develop new agents for CRPC.

For patients with CRPC, the epothilones enhance the list of current therapeutic options, particularly because they are found to stabilize microtubules and are not as affected by several common resistance pathways that affect drugs such as docetaxel. Phase I and II clinical trial results with ixabepilone indicate activity across a spectrum of patients, ranging from patients who are treatment naïve to patients who have received several lines of therapy. PSA responses have been observed with ixabepilone as monotherapy and in combination with mitoxantrone and prednisone or estramustine. DLTs include neutropenia and neuropathy. Myeloid growth factors may be used to mitigate the rate of significant neutropenia. Neuropathy is generally related to prior exposure to neurotoxic agents, the cumulative epothilone dose, and the dose duration [61].

The standard approach for defining a role for epothilones in CRPC patients would be to undertake a conventional phase III trial comparing OS with an epothilone-containing regimen versus a standard-of-care agent (docetaxel in chemotherapy-naïve CRPC patients or mitoxantrone for second-line CRPC treatment). However, the absence of surrogate endpoints for OS hinders this strategy, because such a design requires a large number of patients to detect a small difference and results would not be available for years. Furthermore, such trials face accrual difficulties as novel biologic therapies emerge from current trials as useful adjuncts to standard docetaxel chemotherapy or as promising agents for second- and third-line treatment. A novel approach might be to incorporate insights about taxane resistance into clinical trial design, for instance, selecting an enriched population for whom epothilone-based treatment may be more likely to succeed rather than performing a simple head-to-head comparison. In order to identify molecular signatures related to ixabepilone sensitivity in prostate cancer patients, an active phase II trial is evaluating proteomic and gene expression parameters in correlation with ixabepilone as neoadjuvant therapy for high-risk prostate cancer patients prior to radical prostatectomy (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00672009). Additional studies of this nature are critical for designing progressive trials, both to identify optimal populations and to monitor treatment response. At present, until predictive biomarkers are validated, survival is likely to remain the primary endpoint for evaluating new agents [62]. Identifying the most effective epothilone-based regimens and assessing palliative endpoints in addition to PSA responses and impact on survival will facilitate incorporation of epothilones into treatment algorithms for men with CRPC.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Mitchell E. Gross

Collection and/or assembly of data: Mitchell E. Gross, Tanya B. Dorff

Data analysis and interpretation: Mitchell E. Gross

Manuscript writing: Mitchell E. Gross, Tanya B. Dorff

Final approval of manuscript: Mitchell E. Gross, Tanya B. Dorff

The authors take full responsibility for the content of this publication and confirm that it reflects their viewpoint and medical expertise. The corresponding author wishes to acknowledge StemScientific, funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb, for providing writing and editing support. Bristol-Myers Squibb did not influence the content of the manuscript, nor did the author receive financial compensation for authoring the manuscript.

References

- 1.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Fort Washington, PA: NCCN; 2011. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines: Prostate Cancer, V. 3.2011; pp. 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry DL, Moinpour CM, Jiang CS, et al. Quality of life and pain in advanced stage prostate cancer: Results of a Southwest Oncology Group randomized trial comparing docetaxel and estramustine to mitoxantrone and prednisone. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2828–2835. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berthold DR, Sternberg CN, Tannock IF. Management of advanced prostate cancer after first-line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8247–8252. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantoff PW, Halabi S, Conaway M, et al. Hydrocortisone with or without mitoxantrone in men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: Results of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9182 study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2506–2513. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tannock IF, Osoba D, Stockler MR, et al. Chemotherapy with mitoxantrone plus prednisone or prednisone alone for symptomatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer: A Canadian randomized trial with palliative end points. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1756–1764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berthold DR, Pond GR, de Wit R, et al. Survival and PSA response of patients in the TAX 327 study who crossed over to receive docetaxel after mitoxantrone or vice versa. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1749–1753. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg JE, Weinberg VK, Kelly WK, et al. Activity of second-line chemotherapy in docetaxel-refractory hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients: Randomized phase 2 study of ixabepilone or mitoxantrone and prednisone. Cancer. 2007;110:556–563. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caffo O, Sava T, Comploj E, et al. Estramustine plus docetaxel as second-line therapy in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer resistant to docetaxel alone. Urol Oncol. 2010;28:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreicer R, Petrylak D, Agus D, et al. Phase I/II study of bortezomib plus docetaxel in patients with advanced androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1208–1215. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris MJ, Pandit-Taskar N, Stephenson RD, et al. Phase I/II study of docetaxel and 153Sm for castrate metastatic prostate cancer (CMPC): Summary of dose-escalation cohorts and first report on the expansion cohort [abstract 5057] J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:248s. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh WK, Manola J, Ross RW, et al. A phase II trial of docetaxel plus carboplatin in hormone refractory prostate cancer (HRPC) patients who have progressed after prior docetaxel chemotherapy: Preliminary results [abstract 14533] J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:639s. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorff TB, Groshen SG, Wei D, et al. Interim results of a phase II trial of pemetrexed and oxaliplatin as 2nd/3rd line therapy in hormone refractory prostate cancer [abstract 5139] J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:284s. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sartor AO, Petrylak DP, Witjes JA, et al. Satraplatin in patients with advanced hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC): Overall survival (OS) results from the phase III satraplatin and prednisone against refractory cancer (SPARC) trial [abstract 5003] J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:250s. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Lorenzo G, Autorino R, Giuliano M, et al. Phase II trial of gemcitabine, prednisone, and zoledronic acid in pretreated patients with hormone refractory prostate cancer. Urology. 2007;69:347–351. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morant R, Bernhard J, Maibach R, et al. Response and palliation in a phase II trial of gemcitabine in hormone-refractory metastatic prostatic carcinoma. Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) Ann Oncol. 2000;11:183–188. doi: 10.1023/a:1008332724977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodney A, Dieringer P, Mathew P, et al. Phase II study of capecitabine combined with gemcitabine in the treatment of androgen-independent prostate cancer previously treated with taxanes. Cancer. 2006;106:2143–2147. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spicer J, Plunkett T, Somaiah N, et al. Phase II study of oral capecitabine in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8:364–368. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morant R, Bernhard J, Dietrich D, et al. Capecitabine in hormone-resistant metastatic prostatic carcinoma—a phase II trial. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1312–1317. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellerhorst JA, Tu SM, Amato RJ, et al. Phase II trial of alternating weekly chemohormonal therapy for patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:2371–2376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daliani DD, Assikis V, Tu SM, et al. Phase II trial of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dexamethasone in the treatment of androgen-independent prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:561–567. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Low J, Wedam S, Lee JJ, et al. Phase II clinical trial of ixabepilone (BMS-247550), an epothilone B analog, in metastatic and locally advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2726–2734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez EA, Lerzo G, Pivot X, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixabepilone (BMS-247550) in a phase II study of patients with advanced breast cancer resistant to an anthracycline, a taxane, and capecitabine. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3407–3414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas ES, Gomez HL, Li RK, et al. Ixabepilone plus capecitabine for metastatic breast cancer progressing after anthracycline and taxane treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5210–5217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee FY, Borzilleri R, Fairchild CR, et al. BMS-247550: A novel epothilone analog with a mode of action similar to paclitaxel but possessing superior antitumor efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1429–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Khan IA, et al. Structure of tubulin at 6.5 A and location of the Taxol-binding site. Nature. 1995;375:424–427. doi: 10.1038/375424a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee FY, Borzilleri R, Fairchild CR, et al. Preclinical discovery of ixabepilone, a highly active antineoplastic agent. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;63:157–166. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0724-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee FY, Smykla R, Johnston K, et al. Preclinical efficacy spectrum and pharmacokinetics of ixabepilone. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodin S, Kane MP, Rubin EH. Epothilones: Mechanism of action and biologic activity. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2015–2025. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haimeur A, Conseil G, Deeley RG, et al. The MRP-related and BCRP/ABCG2 multidrug resistance proteins: Biology, substrate specificity and regulation. Curr Drug Metab. 2004;5:21–53. doi: 10.2174/1389200043489199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou SF, Wang LL, Di YM, et al. Substrates and inhibitors of human multidrug resistance associated proteins and the implications in drug development. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:1981–2039. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newman RA, Yang J, Raymond M, et al. Antitumor efficacy of 26-fluoroepothilone B against human prostate cancer xenografts. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;48:319–326. doi: 10.1007/s002800100323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Reilly T, McSheehy PM, Wenger F, et al. Patupilone (epothilone B, EPO906) inhibits growth and metastasis of experimental prostate tumors in vivo. Prostate. 2005;65:231–240. doi: 10.1002/pros.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altmann KH. Recent developments in the chemical biology of epothilones. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:1595–1613. doi: 10.2174/1381612053764715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sepp-Lorenzino L, Balog A, Su DS, et al. The microtubule-stabilizing agents epothilones A and B and their desoxy-derivatives induce mitotic arrest and apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 1999;2:41–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Awada A, Piccart MJ, Jones SF, et al. Phase I dose escalation study of weekly ixabepilone, an epothilone analog, in patients with advanced solid tumors who have failed standard therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0751-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abraham J, Agrawal M, Bakke S, et al. Phase I trial and pharmacokinetic study of BMS-247550, an epothilone B analog, administered intravenously on a daily schedule for five days. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1866–1873. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aghajanian C, Burris HA, 3rd, Jones S, et al. Phase I study of the novel epothilone analog ixabepilone (BMS-247550) in patients with advanced solid tumors and lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1082–1088. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.7304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gadgeel SM, Wozniak A, Boinpally RR, et al. Phase I clinical trial of BMS-247550, a derivative of epothilone B, using accelerated titration 2B design. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6233–6239. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mani S, McDaid H, Hamilton A, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of BMS-247550, a novel derivative of epothilone B, in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1289–1298. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0919-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chi K, Beardsley E, Venner P, et al. A phase II study of patupilone in patients with metastatic hormone refractory prostate cancer (HRPC) who have progressed after docetaxel [abstract 5166] J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:290s. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galsky MD, Small EJ, Oh WK, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of the epothilone B analog ixabepilone (BMS-247550) with or without estramustine phosphate in patients with progressive castrate metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1439–1446. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graff J, Smith D, Neerukonda L, et al. Phase II study of sagopilone (ZK-EPO) plus prednisone as first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer (AIPC) [abstract 5141] J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:284s. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harzstark A, Rosenberg J, Weinberg V, et al. A phase II study of ixabepilone, mitoxantrone, and prednisone in patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) refractory to docetaxel-based therapy [abstract 160]. Presented at the 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology Genitourinary Cancers Symposium; February 26–28, 2009; Orlando, Florida. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hussain A, DiPaola RS, Baron AD, et al. Phase II trial of weekly patupilone in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:492–497. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hussain M, Tangen CM, Lara PN, Jr, et al. Ixabepilone (epothilone B analogue BMS-247550) is active in chemotherapy-naive patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: A Southwest Oncology Group trial S0111. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8724–8729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smaletz O, Galsky M, Scher HI, et al. Pilot study of epothilone B analog (BMS-247550) and estramustine phosphate in patients with progressive metastatic prostate cancer following castration. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1518–1524. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu G, Chen Y, DiPaola RS, et al. Final results on phase II study of a weekly schedule of ixabepilone in patients with metastatic castrate-refractory prostate cancer (E3803): A trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [abstract 4529] J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:250s. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kreis W, Budman DR, Calabro A. Unique synergism or antagonism of combinations of chemotherapeutic and hormonal agents in human prostate cancer cell lines. Br J Urol. 1997;79:196–202. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.06310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Speicher LA, Barone L, Tew KD. Combined antimicrotubule activity of estramustine and Taxol in human prostatic carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1992;52:4433–4440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berry WR, Hathorn JW, Dakhil SR, et al. Phase II randomized trial of weekly paclitaxel with or without estramustine phosphate in progressive, metastatic, hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2004;3:104–111. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2004.n.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hudes GR, Greenberg R, Krigel RL, et al. Phase II study of estramustine and vinblastine, two microtubule inhibitors, in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1754–1761. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.11.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harzstark AL, Rosenberg JE, Weinberg VK, et al. Ixabepilone, mitoxantrone, and prednisone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after docetaxel-based therapy: A phase 2 study of the department of defense prostate cancer clinical trials consortium. Cancer. 2010 Dec 29; doi: 10.1002/cncr.25810. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenberg JE, Ryan CJ, Weinberg VK, et al. Phase I study of ixabepilone, mitoxantrone, and prednisone in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer previously treated with docetaxel-based therapy: A study of the department of defense prostate cancer clinical trials consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2772–2778. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rubin EH, Rothermel J, Tesfaye F, et al. Phase I dose-finding study of weekly single-agent patupilone in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9120–9129. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wojtowicz M, Rothermel JD, Anderson J, et al. Phase I dose-escalation trial investigating the safety and tolerability of EPO906 plus estramustine in patients with advanced cancer [abstract 4623] J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:411. [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Bono JS, Logothetis C, Fizazi K, et al. Abiraterone acetate (AA) plus low dose prednisone (P) improves overall survival (OS) in patients (Pts) with metastatic castrationresistant prostate cancer (MCRPC) who have progressed after docetaxel-based chemotherapy (Chemo): Results of COU-AA-301, a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase III study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:LBA5. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee JJ, Swain SM. Peripheral neuropathy induced by microtubule-stabilizing agents. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1633–1642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berry W, Eisenberger M. Achieving treatment goals for hormone-refractory prostate cancer with chemotherapy. The Oncologist. 2005;10(suppl 3):30–39. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-90003-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harzstark A, Weinberg V, Sharib J, et al. Second-line combination chemotherapy: A phase I study of ixabepilone, mitoxantrone, and prednisone in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer (CRPC) refractory to docetaxel-based therapy [abstract 5151] J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:287s. [Google Scholar]